Abstract

The use of pathogen-resistant cultivars is expected to increase yield and decrease fungicide use in agriculture. However, in potato breeding, increased resistance obtained via resistance genes (R-genes) is hampered because R-gene(s) are often specific for a pathogen race and can be quickly overcome by the evolution of the pathogen. In parallel, susceptibility genes (S-genes) are important for pathogenesis, and loss of S-gene function confers increased resistance in several plants, such as rice, wheat, citrus and tomatoes. In this article, we present the mutation and screening of seven putative S-genes in potatoes, including two DMR6 potato homologues. Using a CRISPR/Cas9 system, which conferred co-expression of two guide RNAs, tetra-allelic deletion mutants were generated and resistance against late blight was assayed in the plants. Functional knockouts of StDND1, StCHL1, and DMG400000582 (StDMR6-1) generated potatoes with increased resistance against late blight. Plants mutated in StDND1 showed pleiotropic effects, whereas StDMR6-1 and StCHL1 mutated plants did not exhibit any growth phenotype, making them good candidates for further agricultural studies. Additionally, we showed that DMG401026923 (here denoted StDMR6-2) knockout mutants did not demonstrate any increased late blight resistance, but exhibited a growth phenotype, indicating that StDMR6-1 and StDMR6-2 have different functions. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on the mutation and screening of putative S-genes in potatoes, including two DMR6 potato homologues.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Potatoes (Solanum tuberosum L.) are the third-fourth most important staple crop worldwide with 450 million tons produced in 2018 (www.fao.org) and are a major and irreplaceable part of the human diet in some countries1. Potatoes have potential for extraordinarily high yield, have a high nutritional value, and are a good source of energy, minerals, protein, fats, and vitamins2. However, potato crops are affected by pests and many diseases, such as late blight, early blight, bacterial wilt, potato blacklegs, Colorado potato beetles, and cyst nematodes (https://cipotato.org/crops/potato/potato-pests-diseases/).

Late blight is the most serious disease of potato crops worldwide. It is caused by the oomycete pathogen Phytophthora infestans, which can infect the leaves, stems, and tubers of potato plants. Under favourable conditions like moderate temperatures and moderate to high humidity, an unprotected potato field with a late blight susceptible cultivar can be destroyed in matter of days by P. infestans infection3. The control of late blight disease is mainly dependent on the use of fungicides and to a less degree resistant potato varieties. Normally, several fungicide sprays are applied during a cropping season to control late blight disease4. Resistant potato crop varieties require less fungicide use; therefore, use of resistant crops is a more sustainable method for control of late blight. Late blight-resistant potato varieties have been developed for more than a century by introgression of resistance genes (R-genes) from wild Solanum species5. However, virulent races of P. infestans have rapidly evolved to overcome all 11 major R-genes introduced from S. demissum3. Recently, breeders have tried to combine several R-genes from different wild Solanum relatives to increase late blight resistance in potatoes6,7. However, classical breeding by recurrent selection is time-consuming as well as complicated in tetraploid potatoes.

Another type of resistance, based on the loss-of-function of a susceptibility gene (S-gene), has more recently been described. S-genes are utilized by the pathogen during colonization and infection. Therefore, the knockout of S-genes may induce recessive resistance in plants8. One typical S-gene is MLO (Mildew Locus O), which was originally characterized in spring barley in the 1940s and later used in European plant breeding programs in the 1970s. Because it provides nonspecific durable resistance in the field, MLOs have been used in a wide range of plant crops such as apples, barley, cucumbers, grapevines, melons, peas, tomatoes, and wheat9,10,11. Based on biological function, S-genes have been divided into three groups12,13. The first group includes genes needed for host recognition by the pathogen. One example is GLOSSY 11 in maize12. The second group comprises genes that support pathogen demands, such as SWEET sugar transporters. The third group includes genes that control plant defence responses. Many S-genes encode negative regulators of plant defence responses, such as DMR6, TTM2, and LSD1. Using RNAi silencing, Sun et al. (2016) identified some S-genes in potatoes, including StDND1 and StDMR6 that upon knockdown showed enhanced late blight resistance. However, downregulation of homologous genes can cause undesirable phenotypes, or silencing of the introduced transgene may produce uneven results using the RNAi method. Finally, RNAi approaches are clearly classified as genetically modified organisms (GMOs).

Recently, genome editing technologies have progressed and become powerful genetic tools for increasing pathogen resistance in plants14. These technologies include the use of transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) or clustered regularly interspaced short palindrome repeats (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas9)14,15. CRISPR-Cas is the preferred genome editing tool because of both the versatile and easy design, which only requires replacement of the sgRNA to confer new target specificity. This makes it cost and labour effective, as well as giving it the ability to produce transgene-free offspring14,16. Recently, CRISPR-Cas has been used to knock out elF4E in cucumbers, SWEET14 in rice, CsLOB1 in citrus, and DMR6-1 or JAZ2 in tomatoes17, but it has not been applied in tetraploid potatoes for enhanced disease resistance18. In potato, gene editing has been used for improving of tuber quality traits16,19,20.

Most potato cultivars used commercially are tetraploid and rarely produce berries21. Therefore, increased resistance of these cultivars by traditional breeding methods is laborious, and finding natural or chemical mutants, which are mutated in all four alleles, is exceedingly difficult and cumbersome. Čermák et al. (2017) developed a whole array of CRISPR-Cas9 vectors, which were used to produce deletion mutants on diploid plants, such as tomatoes and Medicago. Additionally, larger CRISPR/Cas mediated deletions may easily be scored by PCR with primers specific to or flaking the target region22,23.

To produce late blight resistance potato cultivars in the future, we initiated the first step of screening putative S-genes in potatoes. Based on predicted gene function, target candidates in potatoes were selected using the following criteria: pathogen resistance phenotype, small gene family size, and different gene functions and pathways. Seven putative S-genes from the literature were selected (Table 1), and plants with mutated genes were generated by CRISPR/Cas9 and analysed for late blight resistance. Our results demonstrated that StDMR6-1 and StCHL1 are promising S-gene candidates for generating increased late blight resistance in potatoes.

Materials and methods

Materials

Tetraploid Solanum tuberosum Désirée and King Edward (susceptible to late blight infection) were maintained in vitro by sub-culturing the apical portion of 3–4 week-old stems on Murashige and Skoog (MS) basal nutrient including vitamins (Duchefa, M0222.0050) with 10 g/L sucrose and 7.5 g/L Phyto agar (MS10)24. Genetically modified lines containing three resistance genes, 3R, Rpi-blb2, Rpi-blb1, and Rpi-vnt.17,24, in Désirée and King Edward were used as resistant controls. The P. infestans strain 88,069 (A1 mating type, race 1.3.4.7) was propagated as previously described25.

Vector constructs

Candidate genes were selected (Table 1) and the coding sequence analysed for possible CRISPR targets and their number of off-targets using Cas-designer (http://www.rgenome.net/cas-designer);26 and CRISPOR (https://crispor.org);27. For each candidate, two PCR primer pairs were designed to amplify a region containing putative targets with the fewest potential off-targets and used in PCR amplification of genomic DNA and cDNA (see Supplementary Table). PCR products were run on 1% agarose gels, gel-purified, and each band was sequenced using two primers. For each candidate, the two targets that were conserved in all sequences, and that had the lowest number of potential off-targets were selected (see supplementary Fig. 1). The targets were assembled into the Csy4 multi-gRNA vector pDIRECT_22C, using protocol 3A22 to form the plasmid pDIRECT_22C_S-gene.

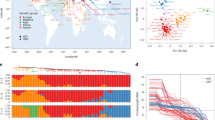

Mean lesion diameter and PCR analysis of potential S-gene mutant lines in potatoes. Lesions caused by Phytophthora infestans strain 88069 were scored after 7 d and PCRs were performed with specific primers (Supplementary Table S1) and run in 2% agarose. (A) StMLO1. (B) StHDS. (C) StTTM2. (D) StDND1. (E) StCHL1. (F) StDMR6-1. (G) StDMR6-2. Error bars shown represent SEM (standard error of the mean) and asterisks denote values significantly different from that of the wild type (*: p < 0.05, **: p < 0.01, t-test, n = 9).

Potato transformation protocol

The protocol for the Agrobacterium transformation of S. tuberosum Désirée and King Edward was modified from the original protocol24,28. A 10 mL overnight liquid culture of Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58 carrying the plasmid of interest was centrifuged at 5000 rpm in a 15 ml tube for 10 min, the supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was re-suspended in 10 mL dH2O containing 50 µl of acetosyringone (76 mM). For transformation, 1 mL of the Agrobacterium suspension (OD 1.9–2.0) was pipetted onto dissected leaf explants that were placed on the co-cultivation media. Leaf explants were incubated under reduced light (50% intensity) for 48 h before they were transferred to selective media (400 mg/L cefotaxime + 100 mg/L kanamycin, and 2 mg/L for Désirée and 5 mg/L for King Edward of zeatin ribose) for regeneration24. Leaf explants were sub-cultured onto fresh media every 7–10 d to maintain selection pressure. Shoots that emerged after 4–5 weeks were dissected and rooted on MS media containing no plant growth regulators but with continued selection (100 mg/L kanamycin). Only shoots that initiated roots in the selective media were screened at the molecular level.

PCR screening and sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted from young leaves of regenerated potato shoots29 and used as a template in the PCR analysis. The PCR reaction mixture contained 1 × Buffer, 1 µL genomic DNA, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 0.5 μM of each primer, and 0.2 U Taq DNA polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) in a final volume of 25 µL. The PCR amplification program was as follows: one cycle of 5 min at 95 °C followed by 35 cycles of 20 s at 94 °C, 20 s at 58 to 64 °C (see table S1), and 30 s at 72 °C, with a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. The samples were analysed on 2% agarose gels (except the CHL gene, 3% agarose gels were used) and tetra-allelic deletion mutant lines were selected (except the HDS gene, see results). Each PCR band was isolated from agarose gels and purified using a GeneJET Gel Extraction Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA). Purified samples were sequenced at Eurofins Genomics (Germany), see supplementary figure S2.

In-vitro propagation and in-vitro long-term storage

Selected mutant lines were propagated by cutting node segments and culturing them in 90 × 25 mm Petri dishes containing 25 mL MS10 medium. The plates were sealed with micropore medical sealing tape and grown in a tissue culture room (20 °C, 16 h photoperiod, 40–60 μmol/m2/s). After 14 d, three rooted plants (for each mutant line) were transferred onto the soil for further analysis. To maintain each line in vitro, 1 to 2 shoots were transferred into a Petri dish containing MS10 medium, sealed with Parafilm, cultured for 4 weeks in a tissue culture room; thereafter, the in-vitro line was maintained at 9 °C, 8 h photoperiod, 10 μmol/m2/s for 6 months30.

Growth phenotype study and generation of leaf material for pathogenic resistance assay

In-vitro plants of the wild type, 3R, and tetra-allelic deletion mutant lines were grown in 2 L plastic pots containing potting soil (Emmaljunga Torvmull AB, S 28,022 Vittsjö, Sweden). All plants were grown for 5 to 6 weeks in climatized rooms (20 °C, 16 h photoperiod, 160 μmol/m2/s, 65% relative humidity [RH]) with watering every second day31.

Detached-leaf assay

For each experiment, nine fully developed leaves from 5-week-old plants from each line were used for detached-leaf assays (DLAs). The inoculum of P. infestans was prepared by harvesting sporangia from 12 to 14 d-old plates of P. infestans in clean tap water32. The inoculum was adjusted to 20,000 sporangia/mL and 25 µL of the spore solution was pipetted onto the abaxial side of the leaflet. The infected leaves were maintained in a humid environment (RH ~ 100%) under controlled conditions33. Results were recorded by measuring the infection size of each leaflet at 7 d post-inoculation (dpi). The difference between the means was tested using a t-test with the significance level of p < 0.05 or 0.01. We also calculated the percentage of successful infection.

Result and discussion

Selection of putative S-genes in Potato against Phytophthora infestans

S-genes involved in susceptibility to different types of pathogens have been found in many different plant species17,34. Here, S-gene candidates were selected based on the following criteria: pathogen resistance phenotype, being either a single gene or belonging to a small confined gene family in potatoes, each S-gene concerning other candidates should have a different function, and if possible, function in different pathways (see Table 1).

MLO (Mildew resistance locus) encodes a plasma membrane-localized seven transmembrane domain protein associated with vesical transport and callose deposition8,9,35. The MLO protein contains a domain that is predicted to bind with calmodulin and is required for full susceptibility to powdery mildew infection9. In this study, we included MLO because it is a typical S-gene, which has been successfully applied in many plants, such as roses, peas, melons, and apples9. Furthermore, mlo mutants also showed resistance to two oomycetes: the hemibiotrophic Phytophthora palmivora10 and the biotrophic Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis36. Because P. infestans also is a oomycete with a hemibiotrophic lifestyle, we decided to include this gene in the screening. Appiano et al. (2015) identified the corresponding MLO gene in potatoes and named it StMLO137.

In Arabidopsis, HDS encodes a chloroplast localized hydroxy-2-methyl-2-(E)-butenyl 4-diphosphate synthase, one of the last steps in the methylerythritol 4-phosphate (MEP) pathway from which chlorophyll, carotenoids, gibberellins, and other isoprenoids are derived38. HDS is a negative regulator of salicylic acid (SA) by reducing the amount of its substrate, methylerythritol cyclodiphosphate (MEcPP)46. Arabidopsis HDS mutant plants show enhanced resistance to biotrophic, but not to necrotrophic, pathogens47. In potatoes, we only encountered one HDS gene homologue.

The triphosphate tunnel metalloenzymes (TTMs) hydrolyse organophosphate substrates39. Arabidopsis encodes three TTM proteins, where TTM2 is involved in pathogen resistance via an enhanced hypersensitive response and elevated SA levels48. Atttm2 mutant lines showed enhanced resistance to the biotrophic pathogen Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis. The closest potato homologues to the AtTTM2 gene are DMG400025117 and DMG400001931. DMG400025117 appeared to be induced by the SA homologue BTH, whereas DMG400001931 was not (http://bar.utoronto.ca/efp_potato/cgi-bin/efpWeb.cgi); therefore, we chose to analyse DMG400025117 since late blight resistance is influenced by SA. Furthermore, as TTM2 has only been studied in Arabidopsis, its relevance in acquiring resistance in crop plants is unknown.

Sun et al. (2016, 2017) analysed potato plants, where StDND1 had been knocked-down using RNAi and found that the plants were more resistant toward P. infestans. StDND1-silenced plants displayed auto-necrotic spots only in the leaves of older plants and a few well-silenced StDND1-transformants showed dwarfing12, a phenotype that might result from inadequate specificity of the RNAi approach or the efficiency of silencing may fluctuate during development. The DND1 gene encodes a cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channel, which has been implicated in Ca2+ signalling related to various physiological processes (pathogen defence, development, and thermotolerance)49.

StCHL1 is a putative S-gene in potatoes. Originally, StCHL1 was found through microarray analysis of brassinosteroid responsive marker genes in potatoes. Gene overexpression and virus-induced gene silencing experiments showed this gene to be important for P. infestans colonization of Nicotiana benthamiana42. No experiments in potato has been carried out. CHL1 is a transcription factor, which regulates brassinosteroid hormone signalling and immune response50; in potatoes, we located only one such gene.

DMR6 proteins belong to the 2-oxoglutarate (2OG)-Fe (II) oxygenase family. In Arabidopsis, AtDMR6 encodes an SA 5-hydroxylase that regulates SA homeostasis by converting SA to 2,5-DHBA45. This gene is a negative regulator of the active SA pool; thus, it is important for the SA-dependent plant immune system. Knockout of SlDMR6-1 in tomatoes enhanced the resistance to Phytophthora capsici and Pseudomonas syringae43. Two DMR6 homologues were identified in potatoes. Knockdown of StDMR6 in potatoes by RNAi showed an unclear resistance phenotype, with only six out of 12 transformed plants showing lower transcript levels of DMR6 and four plants showed a resistance phenotype, whereas eight plants showed susceptibility to Phytophthora infestans12. Therefore, both potato DMR6 homologues were investigated separately by knockout experiments with genome editing.

Efficiency of double guide mediated tetra-allelic mutation varied between genes

By applying two guide RNAs, targeted deletions in the gene of interest may be generated22,23. In a study by Čermák el al. 2017, deletions between the two cleavage sites were far more prevalent than individual indels resulting from cleavage of a single site. Therefore, we used the pDIRECT_22C vector22 encoding two guide RNAs for knocking out S-genes in potatoes. For our screen of edited potato plants, we chose to use PCR with gene-specific primers, spanning both gRNA targets, followed by gel electrophoresis analysis, as a simple, inexpensive, and rapid method for detecting deletions in the target gene. The screening results are shown in Fig. 1 for the lines that were subsequently screened for late blight resistance and growth phenotypes. Sequence data of the target regions is shown in supplementary figure S2.

The number of plants with a deletion in all four alleles was related to locus and target sequence (Table 2). Analysis of shoots showed variation in the prevalence of tetra-allelic deletion mutants ranging from 0 to 18%. This number can be regarded as the minimum number because we did not detect single nucleotide mutations with this PCR method, but because it was easy to generate many lines in potatoes we believe this was the most efficient method. Analysing in silico target efficiency with several different online tools did not reveal a specific tool that could predict the mutation rate better than others (Table 2).

In Arabidopsis, homozygous mutation of HDS caused an albino phenotype and seedling lethality38. In the present study, in agreement with this observation, some calli turned white and did not develop into seedlings. Furthermore, none of the StHDS genome-edited seedlings were confirmed to be deleted in all four alleles. Therefore we concluded that, as in Arabidopsis, a full tetra-allelic HDS deletion is lethal, although transformed cells with a mutation in one, two, or three alleles were able to develop and form shoots (Table 2).

For all other genes, full allelic knockouts were not linked with lethality. Two genes showed a high number of tetra-allelic deletion mutants, namely 13% of StMLO1 and 18% of StCHL1 shoots had a deletion in all four alleles. The other four genes showed a prevalence of between 0.7% and 2.4% tetra-allelic deletion mutants. As mentioned above, because the applied PCR screening did not detect point mutations or very short deletions/insertions, the number of mutants detected in the present study may be lower than that of other screening methods, such as CAPS (Cleaved-Amplified-Polymorphic-Sequence) or IDAA19. However, a combination of constructs expressing two gRNAs with PCR screening of shoots is a low-cost, simple, and fast method enabling large scale screening at the shoot level (Fig. 1, supplementary Fig. 3).

StDND1, StCHL1, and StDMR6-1 tetra-allelic deletion mutants showed enhanced late blight resistance

To analyse late blight resistance in tetra-allelic mutant lines, DLAs were performed. Infection lesion diameter was determined 7 days after P. infestans inoculation (Fig. 1) and the percentage of infected leaves was analysed (Table 3).

Knockout of StMLO1 in potatoes did not increase late blight resistance as evident by the sizes of the lesion or percentage of infected leaves. Nor there any growth phenotype was detected (Fig. 2A). The effect on P. infestans infection in mlo potatoes was tested in the present study for the first time. All eight Stmlo1 mutant lines were as susceptible to late blight disease as the wild type Désirée (Fig. 1A, Table 3). This was somewhat unexpected because the mutation of orthologous MLO genes is effective in many plant and pathogen species36,37, including the hemibiotrophic P. palmivora. Silencing of Capsicum annum CaMLO2 conferred enhanced resistance against virulent Xanthomonas campestris, whereas overexpression of CaMLO2 in Arabidopsis conferred enhanced susceptibility to both Pseudomonas syringae and Hyaloperonospora arabidopsidis36. Recently, a wheat mlo mutant was shown to be susceptible to the hemibiotrophic fungal pathogen Magnaporthe oryzae, whereas it was still resistant to the obligate biotrophic fungus Blumeria graminis11. Thus, the usefulness of MLO is dependent on the host as well as the pathogen.

Phenotypes of mutant lines. (A) mlo at 5-weeks old stage. (B) Wild type Désirée and hds mutant lines at 2-weeks-old stage. (C) Wild type Désirée and one Stttm2 mutant line. (D) Leaf phenotype of wild type and some Stdnd1 mutant lines. (E) Désirée and Stchl1 mutant lines at 5 weeks old. (F) Wild type King Edward and Stdmr6-1 mutant lines at 5 weeks old. (G) Five weeks old wild type Désirée and Stdmr6-2 mutant lines. (H) Wild type King Edward and Stdmr6-2 mutant lines 5 weeks old.

After PCR screening of 169 putative HDS shoots, we did not obtain any tetra-allelic mutant lines (Table 2). After 2 weeks in soil, some heterozygous mutants showed an albino phenotype (Fig. 2B) and did not grow further, whereas shoots with green leaves grew into adult plants. In A. thaliana, the Athds was mutagenized with ethyl methanesulfonate (EMS) and influenced chloroplast development and increased resistance to Pseudomonas syringe47. Our potato Sthds mutants showed weakened growth (Fig. 2B) and P. infestans screening of eight mutant lines did not show increased resistance to late blight disease (Fig. 1, Table 3).

For StTTM2 (DMG400025117), we analysed five tetra-allelic deletion mutant lines. No mutant line showed any altered phenotype (growth, morphology, or pathogen resistance) when compared with wild-type plants (Figs. 1C, 2C). Analysing TTM2 sequences in Solanum tuberosum, two different StTTM2 genes were identified (DMG400025117 and DMG400001931). The study of Ung et al. (2017) suggested that AtTTM1 and AtTTM2 could functionally complement each other; thus, it is plausible that these genes could be functionally complementary to each other and that a double mutant would show resistance to P. infestans in potatoes.

Sun et al. (2016 and 2017) used RNAi to knockdown potato StDND1 and found that these plants were more resistant to P. infestans. However, the plants were smaller and showed early senescence and necrotic spots on leaves of older plants. In line with their results, our data showed that the size of infection lesions was strongly reduced in all Stdnd1 mutant lines, whereas the percentage of successful infections was reduced in some of the tetra-allelic lines (Fig. 1C and Table 3). Two mutant lines with wild type and mutant PCR-bands (DND 44, DND 82) showed auto-necrotic spots and late blight resistance in older, but not young leaves (Figure S4B and S4C).

The tetra-allelic Stdnd1 mutated potato not only exhibited a late blight resistance phenotype (Fig. 1D) as observed from the results of the earlier RNAi study but also showed pleiotropic phenotypes, such as line DND 583 (Fig. 2D). The tetra-allelic Stdnd1 mutant lines, except for the strong resistance phenotype, also showed reduced growth, long and thin stems, as well as necrosis of all leaves (Figure S4A). These latter pleiotropic phenotypes were not found in StDND1 RNAi lines12 maybe because of incomplete silencing. The phenotypes of some of our Stdnd1 mutants (DND 44 and DND 82) and StDND1 RNAi lines were very similar (Figure S4 and Fig. 3C of Sun et al. 2016). In summary, our results indicated that StDND1, due to the pleiotropic phenotypes observed in the Stdnd1 edited lines, was not a good candidate for application in agriculture.

Growth phenotypes of Stdmr6-1 and Stdmr6-2 mutant lines. (A) Growth curve of wild type and Stdmr-1 mutant lines. (B) Fresh weight of 5-week-old wild type and Stdmr6-1 mutant lines. (C) Plant height of wild type and Stdmr6-2 mutant lines. (D) Fresh weight of 5-weeks-old wild type and Stdmr6-2 mutant lines. (E) Tuber morphology of King Edward wild type and its Stdmr6-1 mutant lines. (F) Tuber morphology of King Edward wild type and Stdmr6-2 mutant lines. Error bars show standard variation and asterisks denote values significantly different from that of the wild type, student t-test (**: p < 0.01, n = 4 for King Edward and n = 6 for Désirée).

Stchl1 mutations did not affect morphology or growth phenotype (Fig. 2E). Tetra-allelic mutant plants showed a significant late blight resistance phenotype with reduced lesion sizes (Fig. 1E), but no difference in the percentage of infected leaves (Table 3). This could indicate that the importance of this protein is at the disease developmental stage and not in the initial phase. With a function as a Phytophthora effector target and transcription factor, and being involved in brassinosteroid hormone signalling and immune response to P. infestans50, StCHL1 has clear potential as an useful S-gene; possibly when combined with other S- or R-factors to improve pathogen resistance.

CRISPR/Cas9 was applied to knockdown both StDMR6-1 and StDMR6-2, respectively. Tetra-allelic CRISPR/Cas9 knockdown of StDMR6-1 showed a significant increase in resistance against P. infestans both as measured by infected lesion size and the percentage of infected leaves (Fig. 1F, Table 3). This is in contrast to that of Stdnd1 and Stchl1 knockout plants, which only showed reduced infection lesion sizes (Fig. 1 and Table 3), but no reduction in the percentage of infected leaves. In tomatoes, the CRISPR-Cas9 mediated mutation of the StDMR6-1 ortholog SlDMR6-1 showed increased resistance to P. capsici and P. syringae pv. tomato43, indicating broad-spectrum disease resistance function of DMR6-1. In potatoes, knockdown of StDMR6 by RNAi increased late blight resistance without any documented effect on growth phenotype12. However, only 33% of the RNAi lines showed an increased resistance phenotype12. Tomatoes and potatoes each contain two DMR6 genes (43, Table 1). StDMR6-2 and StDMR6-1 transcripts are approximately 80% identical at the nucleotide level. Because these genes are remarkably similar, RNAi may downregulate both, and therefore knock out of either gene by CRISPR-Cas9 is important for the elucidation of individual gene function.

Genome editing of StDMR6-2 showed that this gene was not involved in susceptibility to P. infestans (Fig. 1G and Table 3). Five tetra-allelic mutants in two potato backgrounds (Désirée and King Edward) showed the same infection lesion size and percentage of infected leaves as that of the wild type. De Toledo Thomazella et al. (2016) did not study tomato SlDMR6-2 further because of the low expression during pathogen infection.

In conclusion, when comparing the DLA results of mutant lines with both wild type (Désirée and King Edward) and an R-gene containing a transgenic line (3R), we identified three genes (StDND1, StCHL1, and StDMR6-1) that when mutated, increased late blight resistance, whereas mutations in StMLO1, StHDS, StTTM2, and StDMR6-2 did not affect late blight resistance in potatoes.

DMR6-1 mutants had no obvious growth-related phenotypes

StDMR6-1 is a promising S-gene because tetra-allelic mutants not only showed increased late blight resistance (Fig. 1F and Table 3) but also did not differ in over-all growth phenotype compared with the wild type (Fig. 2F). Measurement of plant height (Fig. 3A), fresh weight (Fig. 3B) and tuber morphology (Fig. 3E) showed no differences between mutants and wild types. Plants mutated in the orthologous gene SlDMR6-1 in tomatoes, showed disease resistance without any documented effects in growth and development under greenhouse conditions43. Therefore, StDMR6-1 may be used in potato breeding to create new potato cultivars with broad-spectrum disease resistance.

StDMR6-2 affect growth phenotypes in potato

StDMR6-1 and its ortholog SlDMR6-1 are important in pathogen susceptibility (Fig. 1)43 without any obvious growth phenotype (Fig. 3). We investigate the effect of the genome editing of StDMR6-2 on potato phenotype (Figs. 2G,H and 3). Our results did not show any changes in late blight resistance. Analysis of growth phenotype showed that tetra-allelic mutants of StDMR6-2 had significantly lower plant height (Fig. 3C) and fresh weight (Fig. 3D) in both cultivar backgrounds. The plants had the same number of leaves as did the wild type, but their internodes were shorter (Fig. 2G). Furthermore, the tuber eyes of StDMR6-2 mutants did not have the reddish colour (anthocyanin) that is typical of King Edward (Fig. 3F). Moreover, analysis of amino acid domain of StDMR6-2 showed that StDMR6-2 belonged to the 2-oxoglutarate (2OG)-Fe (II) oxygenase family proteins, which are well known for the regulation of secondary metabolism and plant hormones51. Therefore, we hypothesize that StDMR6-2 may function in plant secondary metabolism (anthocyanidin) and may not be involved in late blight resistance. StDMR6-1 and StDMR6-2 share 80% homology at the amino acid level. The nearest solved structure is anthocyanidin synthase from arabidopsis thaliana complexed with naringenin (https://www.rcsb.org/structure/2brt), which when superimposed with StDMR6-1 or StDMR6-2 yields reliability scores52; http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/CPHmodels/) too low to allow for structure prediction/comparison, which could shed light on potential substrate/functionality differences between StDMR6-1 and StDMR6-2.

Conclusion

Using CRISPR-Cas9 mediated loss of gene function of seven putative S-genes, we showed that three putative S-genes (StDND1, StCHL1, and StDMR6-1) were involved in late blight susceptibility. Among these three, StDMR6-1 and StCHL1 emerged as promising S-gene targets for the breeding of new disease resistance cultivars because they did not show any growth related phenotype. We also concluded that the pDIRECT_22C vector and the applied deletion screening system expressing two gRNAs for fast PCR mediated screening of full or partial allele knockout was highly efficient and applicable in potatoes. We have produced gene-edited material in popular cultivars that are ready for further tests in field trials.

References

Eriksson, D., Carlson-Nilsson, U., Ortíz, R. & Andreasson, E. Overview and breeding strategies of table potato production in sweden and the fennoscandian region. Potato Res. 59, 279–294 (2016).

Koch, M., Naumann, M., Pawelzik, E., Gransee, A. & Thiel, H. The importance of nutrient management for potato production part II: plant nutrition and tuber quality. Potato Res. 63, 121–137 (2019).

Fry, W. Phytophthora infestans: the plant (and R gene) destroyer. Mol. Plant Pathol. 9, 385–402 (2008).

Mekonen, S. & Tadesse, T. Effect of varieties and fungicides on potato late blight (Phytophthora infestans, (Mont.) de Bary) management. Agrotechnology 07, 2–5 (2018).

Roman, M. L. et al. R/Avr gene expression study of Rpi-vnt1.1 transgenic potato resistant to the Phytophthora infestans clonal lineage EC-1. Plant Cell Tissue Organ. Cult. 131, 259–268 (2017).

Zhu, S., Li, Y., Vossen, J. H., Visser, R. G. F. & Jacobsen, E. Functional stacking of three resistance genes against Phytophthora infestans in potato. Trans. Res. 21, 89–99 (2012).

Ghislain, M. et al. Stacking three late blight resistance genes from wild species directly into African highland potato varieties confers complete field resistance to local blight races. Plant Biotechnol. J. 17, 1119–1129 (2019).

Pessina, S. Role of MLO genes in susceptibility to powdery mildew in apple and grapevine (Wageningen University, Wageningen NL, 2016).

Kusch, S. & Panstruga, R. Mlo-based resistance: an apparently universal ‘weapon’ to defeat powdery mildew disease. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 30, 179–189 (2017).

Le Fevre, R., O’Boyle, B., Moscou, M. J. & Schornack, S. Colonization of barley by the broad-host hemibiotrophic pathogen phytophthora palmivora uncovers a leaf development-dependent involvement of mlo. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. https://doi.org/10.1094/mpmi-12-15-0276-r (2016).

Gruner, K. et al. Evidence for allele-specific levels of enhanced susceptibility of wheat mlo mutants to the hemibiotrophic fungal pathogen magnaporthe oryzae pv Triticum. Genes 11, 1–21 (2020).

Sun, K. et al. Silencing of six susceptibility genes results in potato late blight resistance. Trans. Res. 25, 731–742 (2016).

Engelhardt, S., Stam, R. & Hückelhoven, R. Good riddance? Breaking disease susceptibility in the era of new breeding technologies. Agronomy https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy8070114 (2018).

Chen, K., Wang, Y., Zhang, R., Zhang, H. & Gao, C. CRISPR/Cas genome editing and precision plant breeding in agriculture. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 70, 667–697 (2019).

Nicolia, A. et al. Targeted gene mutation in tetraploid potato through transient TALEN expression in protoplasts. J. Biotechnol. 204, 17–24 (2015).

Andersson, M. et al. Genome editing in potato via CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoprotein delivery. Physiol. Plant. 164, 378–384 (2018).

Yin, K. & Qiu, J. L. Genome editing for plant disease resistance: Applications and perspectives. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Biol. Sci 374, 20180322 (2019).

Hameed, A., Zaidi, S. S. E. A., Shakir, S. & Mansoor, S. Applications of new breeding technologies for potato improvement. Front. Plant Sci. 9, 1–15 (2018).

Johansen, I. E. et al. High efficacy full allelic CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing in tetraploid potato. Sci. Rep. 9, 1–7 (2019).

Nakayasu, M. et al. Generation of α-solanine-free hairy roots of potato by CRISPR/Cas9 mediated genome editing of the St16DOX gene. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 131, 70–77 (2018).

Sevestre, F., Facon, M., Wattebled, F. & Szydlowski, N. Facilitating gene editing in potato: a Single-Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) map of the Solanum tuberosum L. cv. Desiree genome. Sci. Rep. 10, 1–8 (2020).

Čermák, T. et al. A multi-purpose toolkit to enable advanced genome engineering in plants. Plant Cell 29, tpc.009222016.2016 (2017).

Srivastava, V., Underwood, J. L. & Zhao, S. Dual-targeting by CRISPR/Cas9 for precise excision of transgenes from rice genome. Plant Cell Tissue Organ. Cult. 129, 153–160 (2017).

Wang, E. S., Kieu, N. P., Lenman, M. & Andreasson, E. Tissue culture and refreshment techniques for improvement of transformation in local tetraploid and diploid potato with late blight resistance as an example. Plants 9, 695 (2020).

Hodgson, W. A. & Grainger, P. N. Culture of phytophthora infestans on artificial media prepared from rye seeds. Can. J. Plant Sci. 44, 853 (1964).

Park, J., Bae, S. & Kim, J. Sequence analysis Cas-Designer : a web-based tool for choice of CRISPR-Cas9 tar- get sites. Bioinformatics 31, 1–3 (2015).

Haeussler, M. et al. Evaluation of off-target and on-target scoring algorithms and integration into the guide RNA selection tool CRISPOR. Genome Biol. 17, 1–12 (2016).

Visser, R.G.F. Regeneration and Transformation of Potato by Agrobacterium Tumefaciens. In Plant Tissue Culture Manual Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany vol. 5 (1991).

Edwards, K., Johnstone, C. & Thompson, C. A simple and rapid method for the preparation of plant genomic DNA for PCR analysis. Nucl. Acids Res. 19, 1991 (1991).

Kieu, N.P., Lenman, M. & Andreasson, E. Potato as a Model for Field Trials with Modified Gene Functions in Research and Translational Experiments in “Solanum Tuberosum: Methods and Protocols”. (Springer, 2021).

Bengtsson, T. et al. Proteomics and transcriptomics of the BABA-induced resistance response in potato using a novel functional annotation approach. BMC Genom. 15, 1–19 (2014).

Goth, R. W. & Keane, J. A detached-leaf method to evaluate late blight resistance in potato and tomato. Am. J. Potato Res. 74, 347–352 (1997).

Abreha, K. B., Alexandersson, E., Vossen, J. H., Anderson, P. & Andreasson, E. Inoculation of transgenic resistant potato by Phytophthora infestans affects host plant choice of a generalist moth. PLoS ONE 10, 2–13 (2015).

Zaidi, S. S. E. A., Mukhtar, M. S. & Mansoor, S. Genome Editing: Targeting Susceptibility Genes For Plant Disease Resistance. Trends Biotechnol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tibtech.2018.04.005 (2018).

Kusch, S. et al. Arabidopsis mlo3 mutant plants exhibit spontaneous callose deposition and signs of early leaf senescence. Plant Mol. Biol. 101, 21–40 (2019).

Kim, D. S. & Hwang, B. K. The pepper MLO gene, CaMLO2, is involved in the susceptibility cell-death response and bacterial and oomycete proliferation. Plant J. 72, 843–855 (2012).

Appiano, M. et al. Identification of candidate MLO powdery mildew susceptibility genes in cultivated Solanaceae and functional characterization of tobacco NtMLO1. Trans. Res. 24, 847–858 (2015).

Zhang, L. et al. SEED CAROTENOID DEFICIENT functions in isoprenoid biosynthesis via the plastid MEP pathway. Plant Physiol. 179, 1723–1738 (2019).

Ung, H., Moeder, W. & Yoshioka, K. Arabidopsis triphosphate tunnel metalloenzyme2 is a negative regulator of the salicylic acid-mediated feedback amplification loop for defense responses. Plant Physiol. 166, 1009–1021 (2014).

Sun, K. et al. Silencing of DND1 in potato and tomato impedes conidial germination, attachment and hyphal growth of Botrytis cinerea. BMC Plant Biol. 17, 235 (2017).

Clough, S. J. et al. The Arabidopsis dnd1 ‘defense, no death’ gene encodes a mutated cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 9323–9328 (2000).

Turnbull, D. et al. RXLR Effector AVR2 Up-regulates a brassinosteroid-responsive bHLH transcription factor to suppress immunity. Plant Physiol. 14, 356–369 (2017).

De Toledo Thomazella, P.D., Brail, Q., Dahlbeck, D. & Staskawicz, B. CRISPR-Cas9 mediated mutagenesis of a DMR6 ortholog in tomato confers broad-spectrum disease resistance. bioRxiv (2016) https://doi.org/10.1101/064824.

Hu, T. et al. The tomato 2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenase gene SlF3HL is critical for chilling stress tolerance. Horticult. Res. 6, 1–2 (2019).

Wang, J. et al. S5H/DMR6 encodes a salicylic acid 5-hydroxylase that fine-tunes salicylic acid homeostasis. Plant Physiol. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.17.00695 (2017).

Xiao, Y. et al. Retrograde signaling by the plastidial metabolite MEcPP regulates expression of nuclear stress-response genes. Cell https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.038 (2012).

Gil, M. J., Coego, A., Mauch-Mani, B., Jordá, L. & Vera, P. The Arabidopsis csb3 mutant reveals a regulatory link between salicylic acid-mediated disease resistance and the methyl-erythritol 4-phosphate pathway. Plant J. 44, 155–166 (2005).

Ung, H. et al. Triphosphate tunnel metalloenzyme function in senescence highlights a biological diversification of this protein superfamily. Plant Physiol. 175, 473–485 (2017).

Chin, K., Defalco, T. A., Moeder, W. & Yoshioka, K. The arabidopsis cyclic nucleotide-gated ion channels AtCNGC2 and AtCNGC4 work in the same signaling pathway to regulate pathogen defense and floral transition. Plant Physiol. 163, 611–624 (2013).

Turnbull, D. et al. AVR2 targets BSL family members, which act as susceptibility factors to suppress host immunity. Plant Physiol. 180, 571–581 (2019).

Farrow, S. C. & Facchini, P. J. Functional diversity of 2-oxoglutarate/Fe(II)-dependent dioxygenases in plant metabolism. Front. Plant Sci. 5, 1–15 (2014).

Nielsen, M., Lundegaard, C., Lund, O. & Petersen, T. N. CPHmodels-3.0-remote homology modeling using structure-guided sequence profiles. Nucl. Acids Res. 38, 576–581 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by research funds from The Swedish Foundation for Environmental Strategic Research (Mistra Biotech), The Novo Nordisk Foundation (NNF19OC0057208), The Swedish Research Council Formas (2015-442 and 2019-00512), CF Lundström (CF2019-0037), and the Swedish Farmer’s Foundation for Agricultural Research (0-15-20-557). We appreciate Mia Mogren for the excellent technical support.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.A. and M.L. conceived the study, N.P.K. made the plants, and N.P.K. and E.S.W. made pathogen assays. M.L. designed the constructs and B.L.P. made the modelling. All authors contributed to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kieu, N.P., Lenman, M., Wang, E.S. et al. Mutations introduced in susceptibility genes through CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing confer increased late blight resistance in potatoes. Sci Rep 11, 4487 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-83972-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-83972-w

This article is cited by

-

CRISPR/Cas system for the traits enhancement in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.): present status and future prospectives

Journal of Plant Biochemistry and Biotechnology (2024)

-

CRISPR/Cas-mediated germplasm improvement and new strategies for crop protection

Crop Health (2024)

-

CRISPR-Cas9 based molecular breeding in crop plants: a review

Molecular Biology Reports (2024)

-

Colour change in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) tubers by disruption of the anthocyanin pathway via ribonucleoprotein complex delivery of the CRISPR/Cas9 system

Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture (PCTOC) (2024)

-

Loss-of-function of an α-SNAP gene confers resistance to soybean cyst nematode

Nature Communications (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.