Abstract

Fruit-fall provides the transfer of biomass and nutrients between forest strata and remains a poorly understood component of Amazon forest systems. Here we detail fruit-fall patterns including those of Vouacapoua americana a Critically Endangered timber species across 25 km2 of lowland Amazon forest in 2016. We use multi-model comparisons and an ensemble model to explain and interpolate fruit-fall data collected in 90 plots (totaling 4.42 ha). By comparing patterns in relation to observed and remotely sensed biomass estimates we establish the seasonal contribution of V. americana fruit-fall biomass. Overall fruit-fall biomass was 44.84 kg ha−1 month−1 from an average of 44.55 species per hectare, with V. americana dominating both the number and biomass of fallen fruits (43% and 64%, number and biomass respectively). Spatially explicit interpolations provided an estimate of 114 Mg dry biomass of V. americana fruit-fall across the 25 km2 area. This quantity represents the rapid transfer by a single species of between 0.01 and 0.02% of the overall above ground standing biomass in the area. These findings support calls for a more detailed understanding of the contribution of individual species to carbon and nutrient flows in tropical forest systems needed to evaluate the impacts of population declines predicted from short (< 65 year) logging cycles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The study of the dynamics and distribution of forest fruiting is central for understanding forest regeneration and the dynamics of forest ecosystems1,2,3,4. This is a largely under-studied phenomenon, particularly in highly diverse Amazonian forests. Fruit-fall is the part of forest fruit production that is unused/missed by canopy frugivores5. The availability of fallen fruit therefore depends on not only reproductive phenology but also weather (wind and rain) and the plant-animal interactions with both canopy and terrestrial frugivores1,5,6. Fruit-fall biomass whilst not in absolute terms as important as timber provides an immediately available release of resources for myriad consumers that are key to maintaining the diversity of tropical forest systems4,7,8. Despite their importance, fruit-fall patterns are one of the myriad below canopy components of Amazon forest diversity that have yet to be adequately explained or predicted.

Although fruit production is a critical link for tropical forest biodiversity networks3,4 such ecological interactions are not included to inform logging quotas that establish the quantity and frequency of timber harvests or impact assessments that establish environmental compensation of logging activities across Amazon forests. Selective logging may reduce overall impacts on biodiversity, yet there is increasing evidence that the selective harvest of commercially attractive but rare emergent trees can degrade ecosystem services provided by tropical forests9,10. Large emergent trees (> 60 cm diameter at breast height) are typically rare but have a disproportionate effect on tropical forest diversity, carbon stocks and ecosystem services3,11,12,13. Additionally, ecologically ‘rare’ trees constitute majorities in commercially logged species assemblages and overly simplistic reduced impact logging quotas can lead to unsustainable declines in rare but commercially valuable species14.

Brazil retains 64% of the world’s total intact forest landscapes, of which 72% of natural forests are in Amazonia15. Yet growing political pressure is increasing the number and scale of legal forest logging concessions across the Brazilian Amazon including within protected areas16,17. Although managing yields of selectively-logged forests is crucial for the long-term integrity of forest biodiversity and financial viability of local industries, overly general quotas governing legal concessions can lead to the ecologic and/or economic extinction of target species14,18,19. A basin wide analysis of authorized logging in private and community-owned forests showed no evidence of recovery in total value of forest stands beyond the first-cut, suggesting that the commercially most valuable timber species become predictably rare or economically extinct19. Additionally due to climatic influences on tree mortality20 and growth21 droughts can substantially reduce stocks, biomass and timber recovery rates in areas managed under reduced impact logging regimes22.

The internationally valuable and Critically Endangered timber species Vouacapoua americana23 is unlikely to persist ecologically or economically under recommended reduced impact logging systems in Brazil. Although most valued for timber V. americana is an evolutionarily24 and ecologically25,26 important species, producing large “megafaunal” seeds (average of 32 g fresh-mass and 16 g dry-mass per seed) during two to three month mast fruiting events25,27,28. As a nationally redlisted (Endangered) species it is illegal to harvest V. americana for timber in Brazil29. The existing legal regulations are however ambiguous. For example, a recent process to establish 264,500 ha of commercial logging concessions in the Amapá National Forest (a Brazilian sustainable use protected area) states that threatened timber species are “immune” from cutting (i.e. commercial timber harvest of nationally threatened species is not permitted). But at the same time the same process includes V. americana as a species for commercial exploitation, with options of 25, 30 or 35 year cutting cycles (http://www.florestal.gov.br/documentos/concessoes-florestais/amapa-licitacao, documents accessed 4 January 2021).Yet, studies from French Guiana. using simulations under more precautionary logging regimes (typical for French Guiana), with large cutting diameter (> 60 cm diameter) and long cutting cycles (65 years), showed V. americana would experience unsustainable decreases in both number and basal area18. Additionally, monitoring of regeneration/recruitment patterns is not compulsory within Brazilian logging concessions, with the monitoring of forest growth dynamics merely suggested as an optional component.

Fruit-fall patterns are an important part of recruitment and ecosystem services that are not usually included in general projections of biomass and carbon models30,31,32,33. Although patterns in overall fruit production have been relatively well studied in several Neotropical locations e.g. Cocha Cachu1, Barro Colorado34 and Nouragues35, there remain few fruit-fall data from across the Amazon basin. Mast fruiting is a synchronous and massive production of fruit at long (supra-annual) intervals by plant populations36,37. Slow production rates and synchronization can allow masting trees to accumulate carbon, flush massively, and escape from herbivore attacks37. However, we still lack an understanding of the ecological factors that determine spatio-temporal variability of seed production in Amazonian masting species such as V. americana. Indeed, the contribution of biomass produced (V. americana can produce 4000 fruits, representing ≈ 100 kg of fresh mass per tree) has not been evaluated in this rapidly declining species.

The objectives of this study were to: (1) quantify and explain variation in the occurrence and biomass of fallen fruits of V. americana, (2) predict meso-scale patterns across 25 km2 using topographic, hydrographic, spatial and vegetation cover variables and (3) determine the contribution of the fallen fruits in terms of overall above ground biomass. This modelling study enables us to provide information on the environmental factors that explain and predict meso-scale patterns of fruit-fall biomass and generate new insight into the role of the endangered species V. americana in biomass and nutrient cycles in lowland Amazon forest systems.

Results

Dominance of Vouacapoua americana fruit-fall

A total of 4.4 ha (n = 90) sample plots provided a representative survey across the range of environmental variables within the 25 km2 Amapá National Forest sample grid (Fig. 1). Between May and June 2016 fallen fruits were recorded from 87 of the 90 plots (Supplementary Fig. S1). Over these 2 months we counted 21,812 fallen fruits (total dry mass collected 398.3 kg) with a diameter ≥ 1 cm in 4.4 ha, representing 1.8% of the 25 km2 ANF grid (Supplementary Table S1). This total included fruits of 86 species from 28 families and 51 genera (Supplementary Table S1). It was possible to identify 81 (94.1%) to species and five (5.9%) to genus (Supplementary Table S1). Fabaceae was the most species rich family with 24.4% of collected species, followed by Sapotaceae (12.7%) and Lecythidaceae (8.1%).

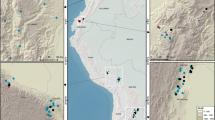

Location of the study site in Amapá National Forest (ANF), Amapá State, north-eastern Brazilian Amazon. (A) State of Amapá in Brazil. (B) Location of ANF in Amapá. (C) Elevation (10-m) across the grid system (white dotted lines); permanent and trail sampling plots (black and pink solid lines respectively) where fruit-fall ground surveys were conducted from May to June 2016. This figure was generated using ArcGIS version 10.8 (https://desktop.arcgis.com/en/arcmap/). Country boundaries and basemaps were obtained from Natural Earth (https://www.naturalearthdata.com/).

From May to June 2016 the number and biomass of fallen fruits was dominated by Vouacapoua americana (43% and 64%, number and biomass respectively, Fig. 2, Supplementary Table S1). Although V. americana was the most dominant and widespread of the fallen fruits (recorded in 62 of 90 plots), there was substantial variation in the number, taxonomic diversity and biomass of fallen fruit between the sampled plots (Table 1, Supplementary Table S1, Supplementary Fig. S1).

Meso-scale fruit-fall patterns

There was substantially more variation in biomass compared with occurrence of V. americana fallen fruits (Fig. 3). Considering the spatial scale of the samples (pairwise distances between plots ranged from 53 to 6642 m), spatial autocorrelation was detected only across relatively short distances (Fig. 3), with complete spatial randomness characterizing the variance in both responses beyond 200 m. The modelled variograms showed relatively high nugget values, representing 50 and 68% of sill values, for fruit-fall occupancy and biomass respectively (Fig. 3).

Spatial patterns in Vouacapoua americana fruit-fall. (A) dry fruit biomass (kg ha−1) recorded in 90 survey plots in the Amapá National Forest. Area of blue spheres proportional to biomass and crosses show plots without fallen fruits. Variograms show spatial autocorrelation patterns for biomass (B) and presence (C) in the 90 plots. Filled points show the estimated empirical variogram values, solid lines are the modelled variogram, and grey shading envelops representing complete spatial randomness obtained by permutation (n = 999 iterations) of the data values.

A combination of spatial, topographic, hydrographic and vegetation cover variables were retained as important for explaining both fruit-fall presence and biomass (Table 2). The spatial model was the most important for explaining patterns in meso-scale masting presence and biomass (Table 2). Topography, hydrography, and vegetation cover models only weakly explained meso-scale biomass patterns (Table 2). In contrast, a relationship with vegetation cover was strongly supported for the meso-scale presence of masting, but topography and hydrography were again only weakly supported. The RMSE of minimal model fitted values (Table 2) was well below the observed SD values for both responses (RMSE = 50.6, 0.35; SD = 74.9, 0.47; biomass, presence respectively).

Spatial predictions

During the survey period, fallen fruit of V. americana were likely to be present in 84.7% (21.1 km2) of the survey grid (Fig. 4). Similar to the observed values, the interpolated distribution of fallen V. americana fruits was not uniform, with 3 clear clusters of absences (Fig. 4). The spatially explicit interpolations provided an overall dry biomass estimate of 114.7 Mg of fallen fruit during the V. americana masting event in the 25 km2 area. The above ground live wood biomass for the survey area derived from previously published remote sensing analysis31,38 was estimated to be between 694,005 and 1,059,500 Mg. Based on our plot wise monthly mean estimate, we can obtain a maximum value of 538.1 kg ha−1 year−1 (44.84 kg ha−1 month−1 × 12). This represents a maximum of 1345 Mg of fallen fruit across the 25 km2 area per year. Therefore, annually the fallen fruits represent a maximum of 0.19% of the aboveground biomass of ANF (1345/694,005 Mg). Our spatially explicit models show that the total masting fruit fall biomass from a single species (V. americana) represents the rapid transfer of between 0.01 and 0.02% and of the overall above ground standing biomass in the area.

Interpolation of Vouacapoua americana fruit-fall. Interpolated biomass across the Amapá National Forest survey grid at 250 m pixel resolution. White spheres with crosses show locations of plots without fallen fruits. Predicted values (color scale, kg ha−1 month−1) are the weighted mean from six methods (Inverse Distance Weight, Universal Kriging, Generalized Additive Model, Generalized Linear Model, Random Forest and Support Vector Machine. For model details see Supplementary S1).

Discussion

Despite the promotion of sustainable use of timber and non-timber resources in tropical forests, the current management criteria still typically lack inclusion of species-specific ecological features. We were able to model the meso-scale distribution of fallen fruit biomass from the critically endangered V. americana. The models enable us to describe, explain and predict meso-scale fruit-fall biomass patterns across 25 km2 of lowland Amazon forest. We found that spatial effects most strongly explained variation in fruit-fall patterns and that the contribution of spatial, topographic, hydrographic and vegetation variables differed between responses. We discuss these findings in relation to what is known regarding fruit-fall patterns across lowland Amazonia and then consider the implications for understanding patterns in biomass below the forest canopy.

Our sample provides a representative snapshot of fruit-fall patterns across the 25 km2 study area. The composition of families and species follows the general pattern found in nearby forest sites and across the Guiana shield39,40,41,42,43,44. We found fallen fruits from four (Crhysophyllum, Licania, Protium and Eschweilera) of the five most abundant genera that Pereira, et al.43 identified in 1.9 ha of nearby (32 km distant) lowland terrra-firme forest. Fabaceae was also the dominant family in a recent inventory of large (> 40 cm DBH) trees, close (< 30 km) to our study area39.

Fruit-fall biomass was similar to values reported by studies from other regions of the Guianan Shield. In the most productive month in the rainy season, Sabatier44 reported a mean of 50 kg ha−1 of fruit-fall production, with 86% of species producing fruits during this season. The less productive soils of the Guianan Shield result in lower values of arboreal species richness2,45. This pattern also appears to be reflected in fruit production46, with values from French Guyana (292 kg ha−1 annual fruit-fall dry biomass) less than half those reported from western Amazonia (e.g. Hanya, et al.46 recorded 796 kg ha−1 of annual fruit-fall dry biomass in Cosha Cashu, Peru).

Clearly V. americana was the main source of fruit-fall, in our study site in 2016. From 20 fruits (representative sample of 10 mature fruits from 2 different trees), we obtained a mean dry mass of 18.2 g, the majority of which was the single seed (90%, mean dry weight from 20 seeds = 16.2 g). This provides an estimate of 72.8 kg (4000 × 18.2 g) of dry fruit per tree. Our dry fallen fruit biomass values therefore represent a range of 1 to 5 fruiting trees per Ha. Our aim was not to estimate tree density, but as these values fall within the expected range reported by previous studies they do reinforce the representativeness of our meso-scale sample. There is an urgent need for additional studies to establish the density and distribution of V. americana in the study area. This data could then enable our model predictions to be validated.

Predicting across a continuous gird enables a variety of analyses that are not possible with sparsely sampled data. Several studies have used remote sensing data to create accurate models of predictions of tropical forest carbon or biomass in diverse scales30,33,47,48,49,50,51,52, but such approaches have not been applied to fruit-fall biomass. The maps presented (Fig. 5) are useful for visualizing the environmental space in more than one dimension and for understanding the predicted responses in the 25 km2 study area. These maps provide a baseline reference that enables evaluation of future management and/or silvicultural actions.

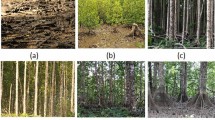

Examples of fruit-fall survey inclusion criteria. Not collected and not counted: (A) Fusaea longifolia (Annonaceae) rotten fruit: (B) Vatairea guianensis (Fabaceae) dried fruit. Counted: (C) Dipteryx odorata (Fabaceae) partially eaten and fresh counted not collected (partially eaten fruit was just counted); (D) Manilkara huberi (Sapotaceae) collected and counted, fresh fruits and seed collected to weigh; (E) Hevea brasiliensis (Euphorbiaceae) counted and removed to avoid repetitive sampling; (F) Vouacapoua americana (Fabaceae) counted and removed. Germinating fruits not collected for weighing and also not counted in a second sampling.

Our model predictions show that field data collection will be necessary to generate robust estimates of fruit-fall biomass and enable evaluation of future management and/or silvicultural actions. These estimates will improve our knowledge about what is being actually conserved and where we can find it within the protected area. However, comparison with fruit-fall patterns in other lowland sites is necessary to enable more rigorous model testing and evaluation. As the spatial structure described may also change significantly over time e.g. plots with low fruit-fall in 2016 may be plots with high fruiting in the following years, additional studies are also required to establish the multi-year patterns of fruit-fall dynamics in the study area.

We found that remotely sensed data provided useful environmental explanatory variables for modelling the distribution of fruit-fall dry biomass. More generally, this study shows remotely sensed variables have potential for predicting meso-scale fruit-fall biomass. More studies are necessary to improve predictive power of biomass models for understanding impacts of compositional changes driven by anthropogenic and climate changes.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

Fieldwork and data collection was conducted under research permit numbers IBAMA/SISBIO 40355-1 and 47859-2 to DN, issued by the Brazilian Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade (ICMBio).

Study area

We sampled fallen fruits at a Brazilian Program for Biodiversity Research (“Programa de Pesquisa em Biodiversidade”—hereafter PPBio53) research grid (25 km2) in the Amapá National Forest (Floresta Nacional do Amapá—hereafter ANF). ANF is a sustainable-use protected area of approximately of 412,000 ha, centered in the state of Amapá, in north-eastern Brazilian Amazon between the Falsino and Araguari rivers (0° 55′ 29″ N, 51° 35′ 45″ W, Fig. 1).

The regional climate is classified by Köppen–Geiger as Am (Equatorial monsoon)54, with an annual rainfall greater than 2000 mm (2240–2510 mm per year from 2010 to 2016)55. The driest months are September to November (total monthly rainfall < 150 mm) and the wettest months from February to April (total monthly rainfall > 300 mm)55 (Supplementary Fig. S2). The ANF is located within the Uatumã-Trombetas moist forest ecoregion (tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests biome) and consists of continuous tropical rainforest vegetation, predominantly never-flooded closed canopy “terra firme” forest56. Canopy trees within the ANF typically reach a height of 25–35 m interspersed with emergent trees reaching up to 50-m56. The soil is predominantly low-fertility oxisols, including a mix of red, yellow and red-yellow latosols following the Brazilian soil classification system56,57.

Study species

Vouacapoua americana is a Critically Endangered (A1cd + 2cd23) endemic to the eastern Guiana shield rainforests24,58. Guiana Shield forests are highly biodiverse, with a more complicated history than temperate and boreal forests, due to a mixture of gradual compositional changes and expansion from refugia45,59. V. americana may be a typical example of this situation, as it shows population contraction in its hypothesized range24,58. V. americana is a large canopy tree with a wide crown that can bear 3000–4000 large (32.6 ± 1.8 g27) single-seeded fruits. It is highly valued for its durable hardwood timber (heartwood density 0.91 g/m3 at 12% moisture content) and pharmacological potential60,61. The density of individuals over 10 cm diameter at breast height (d.b.h.) is of the order of 10 per hectare59,62,63, but varies widely with adults showing a locally clustered distribution65. The spatial distribution of adults depends on abiotic and biotic conditions, including topography and soil hydromorphy, light63,64,65,66 and the availability of short and long range dispersal agents27,63,64.

Long-term studies from French Guiana show V. americana is a mast-seeding species [defined as bimodal seed production with no overlap between two tails36] with an average interval between masting events ranging from 2.366 to 4 years44. Fruiting occurs during a relatively rapid (typically two month) masting event that is synchronized with the wet season27,66. Immature fruits are consumed by primates (including Ateles spp. and Alouatta spp., http://vision.psychol.cam.ac.uk/spectra/guiana/fdiet.html). Fallen seeds may germinate underneath parent trees but this abiotic mode of recruitment is generally unsuccessful for V. americana27,28,66 unless there is a canopy opening nearby28. Intense removal of V. americana seeds leads to high rates of seed dispersal compared with low predation throughout the season27. Most seeds are dispersed approximately 10 m away by rodents (Dasyprocta leporina and Myoprocta exilis)27,63,65, with tapir and peccaries thought to be responsible for longer range dispersal26.

Fruit-fall data collection

Fruit-fall ground surveys are a well-established, relatively efficient and straight forward method to assess fruit production in tropical forests and can reflect seasonal fruiting phenology well5,67. For example, fruit availability, estimated by fruit-fall, positively affected the biomass and the number of species among frugivorous primates46,68. As part of a wider study69,70 fruit-fall surveys were conducted in May and June 2016 that coincided with the fruit-fall of V. americana. Although we did not examine phenological patterns, based on the findings from previous long-term studies44,63,64 we assume that this was a masting fruit-fall event for V. americana.

Within the 25 km2 PPBio grid, a total of 30 regularly spaced (1-km interval) points were sampled (Fig. 1)71. This regular arrangement and sample size of 30 has been shown to be adequate for capturing variation in meso-scale species diversity responses across lowland Amazonia72. At each of the 30 sample points, surveys were conducted along three plots (one permanent plot and two trail plots, Fig. 1). The permanent plots (250 m long) are nonlinear and follow altitudinal contours to minimize the internal variation in both altitude and correlated covariates such as soil type53,71. Additionally, we sampled two linear trail plots (250 m each), one before and the other after the start point of the permanent plots (Fig. 1). Fallen fruit were sampled 1 m to each side of the plot centerlines i.e. covering a total area of 500 m2 (2 × 250 m) for the linear trail plots. This effort provided a total sampled area of 4.42 ha (plot area m2 mean ± SD = 490.7 ± 46.9).

To obtain robust and reproducible estimates of fresh fallen fruit we established a number of inclusion and exclusion criteria6 (Fig. 5). All fresh (i.e. not rotten or desiccated) fallen fruits were counted. Fruits considered unlikely to change in appearance between samples (i.e. Vouacpoua americana, Apeiba sp, Hevea brasiliensis) were removed in order to avoid counting the same fruit twice. Fresh fruits that had been partially eaten were also counted (Fig. 5).

The collected fruits were identified to the lowest taxonomic level (Supplementary Fig. S3) and named following APG III73 by botanists from the Amapá State Scientific Research and Technology Institute (Instituto de Pesquisas Científicas e Tecnológicas do Estado do Amapá, IEPA). To obtain dry fruit biomass estimates the mean dry weight from a maximum of 30 mature fruits of all fallen fruit species was calculated (Supplementary Table S1). Fruits with seeds beginning to germinate were not weighed. The collected fruits were dried to constant weight in an oven at 50 °C and then weighed with a precision balance (fruits < 10 g) or digital balance with error ± 0.01 g (fruits > 10 g). Values of fruit-fall dry biomass were expressed as kg ha−1.

Environmental explanatory variables

Remote sensing data represent continuous measurements of environmental variables that can be applied in ecological studies69,72,74,75. To explain and predict patterns in fallen fruit we used a total of 10 remotely sensed variables (Table 3). These remotely sensed variables were selected to represent meso-scale patterns in topography, hydrography and vegetation cover (Table 3, Supplementary Fig. S4).

Model development

Complementary approaches were adopted to explain and predict patterns in fruit-fall presence and biomass. Firstly, to examine spatial patterns in the responses we used variograms that enable quantification of different aspects of the spatial patterns, including: range (the limit of spatial dependence), nugget (portion of semi-variance attributable to random/environmental factors), and sill (distance at which the variogram becomes constant)78. Then, to examine the environmental factors explaining patterns of fruit-fall presence and dry biomass Generalized Additive Models (GAMs) were employed79,80. GAMs are a nonparametric extension of general linear models that provide the flexibility to model non-parametric and nonlinear relationships that are typical of many ecological patterns. Explanatory GAMs were generated using the “mgcv” package81 using R 3.10 software82. Penalized cubic regression splines determined the shape of nonparametric functions, with the degree of smoothing selected automatically via maximum likelihood using the mgcv package defaults for all models.

To avoid subjective bias in model development we did not examine correlation among variables until after formulation of our a priori models. We applied a two stage approach to explain patterns in the fruit-fall responses. Firstly, separate models were developed to examine the effects of space, topography, hydrography and vegetation cover (Table 2). Within each of our four models, explanatory variables were tested for collinearity. The explanatory power of the models and the level of support for the different hypotheses were examined within a maximum likelihood framework83, with models tested and compared using a combination of model deviance explained81 and information criteria (AIC and BIC)83. The accuracy of model fits were examined using the root mean square error (RMSE) and correlations between observed and fitted values.

Secondly, we obtained the most parsimonious (“minimal”) model, with the most important variables selected using a manual backward stepwise selection based on minimizing AIC values. Manual selection started from the full model without correlated variables, with stepwise exclusion of variables if they did not make a statistically significant (p ≥ 0.05) contribution.

After explaining variation in responses, we then used an ensemble model to predict the presence and dry biomass of masting fruit-fall across the 25 km2 sample grid. The similarity in environmental variable values between the 90 plots and the 25 km2 grid (Table 3) means that we consider the predictions to be an interpolation within the range of environmental values. Ensemble approaches were used to decrease the predictive uncertainty of single-models by combining their projections. The ensemble model was obtained from the weighted mean of six single model methods. The six model algorithms were inverse distance weighted (IDW84), universal kriging (UK84), generalized linear model (GLM), generalized additive model (GAM80), random forest (RF85) and support vector machine (SV86). Predictive models were developed for both presence and biomass with the weighted mean ensemble derived from model predictions weighted by the correlation between observed and predicted values.

Finally, we compared the predicted values with overall live wood biomass. We estimated the range of overall live wood biomass in the 25 km2 study area from two sources31,38. The 500 m resolution mapped values from Baccini et al.31 were used to provide minimum value and the maximum value was estimated by extrapolating the mean (423.8 Mg ha) from Johnson et al.38 across the 25 km2 (2500 ha) area.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Diaz-Martin, Z., Swamy, V., Terborgh, J., Alvarez-Loayza, P. & Cornejo, F. Identifying keystone plant resources in an Amazonian forest using a long-term fruit-fall record. J. Trop. Ecol. 30, 291–301. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266467414000248 (2014).

Terborgh, J. & Andresen, E. The composition of Amazonian forests: Patterns at local and regional scales. J. Trop. Ecol. 14, 645–664 (1998).

Wright, J. S. Plant diversity in tropical forests: A review of mechanisms of species coexistence. Oecologia 130, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004420100809 (2002).

Bascompte, J. & Jordano, P. Plant-animal mutualistic networks: The architecture of biodiversity. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 38, 567–593. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.38.091206.095818 (2007).

Chapman, C. A., Wrangham, R. & Chapman, L. J. Indexes of habitat-wide fruit abundance in tropical forests. Biotropica 26, 160–171. https://doi.org/10.2307/2388805 (1994).

White, L. J. T. Patterns of fruit-fall phenology in the Lopé Reserve, Gabon. J. Trop. Ecol. 10, 289–312. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266467400007975 (1994).

Bello, C. et al. Defaunation affects carbon storage in tropical forests. Sci. Adv. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1501105 (2015).

Peres, C. A., Emilio, T., Schietti, J., Desmoulière, S. J. & Levi, T. Dispersal limitation induces long-term biomass collapse in overhunted Amazonian forests. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 113, 892–897 (2016).

Dee, L. E. et al. When do ecosystem services depend on rare species?. Trends Ecol. Evol. 34, 746–758. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2019.03.010 (2019).

Pinho, B. X., Peres, C. A., Leal, I. R. & Tabarelli, M. In Tropical Ecosystems in the 21st Century (eds Alex, J. D., Edgar, C. T., & Tom, M. F.) Ch. 7, 253–294 (Academic Press, Cambridge, 2020).

Bastin, J.-F. et al. Pan-tropical prediction of forest structure from the largest trees. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 27, 1366–1383. https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12803 (2018).

Lutz, J. A. et al. Global importance of large-diameter trees. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 27, 849–864. https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12747 (2018).

Sist, P., Mazzei, L., Blanc, L. & Rutishauser, E. Large trees as key elements of carbon storage and dynamics after selective logging in the Eastern Amazon. For. Ecol. Manag. 318, 103–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2014.01.005 (2014).

Schulze, M., Grogan, J., Landis, R. M. & Vidal, E. How rare is too rare to harvest? Management challenges posed by timber species occurring at low densities in the Brazilian Amazon. For. Ecol. Manag. 256, 1443–1457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2008.02.051 (2008).

SFB. Florestas do Brasil em resumo 2013: dados de 2007–2012. (2013).

Azevedo-Ramos, C., Silva, J. N. M. & Merry, F. The evolution of Brazilian forest concessions. Elem. Sci. Anth. https://doi.org/10.12952/journal.elementa.000048 (2015).

Golden Kroner, R. E. et al. The uncertain future of protected lands and waters. Science 364, 881. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aau5525 (2019).

Degen, B. et al. Impact of selective logging on genetic composition and demographic structure of four tropical tree species. Biol. Cons. 131, 386–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2006.02.014 (2006).

Richardson, V. A. & Peres, C. A. Temporal decay in timber species composition and value in Amazonian logging concessions. PLoS ONE 11, e0159035. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0159035 (2016).

Aleixo, I. et al. Amazonian rainforest tree mortality driven by climate and functional traits. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 384–388. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-019-0458-0 (2019).

Nepstad, D. et al. Amazon drought and its implications for forest flammability and tree growth: A basin-wide analysis. Glob. Change Biol. 10, 704–717 (2004).

Vidal, E., West, T. A. & Putz, F. E. Recovery of biomass and merchantable timber volumes twenty years after conventional and reduced-impact logging in Amazonian Brazil. For. Ecol. Manag. 376, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2016.06.003 (2016).

Varty, N. & Guadagnin, D. L. Vouacapoua americana. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: e.T33918A9820054, https://doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.1998.RLTS.T33918A9820054.en (1998).

Dutech, C., Maggia, L., Tardy, C., Joly, H. I. & Jarne, P. Tracking a genetic signal of extinction-recolonization events in a neotropical tree species: Vouacapoua americana aublet in french guiana. Evolution 57, 2753–2764 (2003).

Guimarães, P. R. Jr., Galetti, M. & Jordano, P. Seed dispersal anachronisms: Rethinking the fruits extinct megafauna ate. PLoS ONE 3, e1745. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0001745 (2008).

Traissac, S. & Pascal, J. P. Birth and life of tree aggregates in tropical forest: Hypotheses on population dynamics of an aggregated shade-tolerant species. J. Veg. Sci. 25, 491–502. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvs.12080 (2014).

Forget, P.-M. Seed-dispersal of Vouacapoua americana (Caesalpiniaceae) by caviomorph rodents in French Guiana. J. Trop. Ecol. 6, 459–468. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266467400004867 (1990).

Jansen, P. A., Bongers, F. & van der Meer, P. J. Is farther seed dispersal better? Spatial patterns of offspring mortality in three rainforest tree species with different dispersal abilities. Ecography 31, 43–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2007.0906-7590.05156.x (2008).

MMA. Vol. 18/12/2014 (ed Ministério do Meio Ambiente—MMA) 110–121 (Diário Oficial da União, Brasilia, 2014).

Avitabile, V. et al. An integrated pan-tropical biomass map using multiple reference datasets. Glob. Change Biol. 22, 1406–1420. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13139 (2016).

Baccini, A. et al. Estimated carbon dioxide emissions from tropical deforestation improved by carbon-density maps. Nat. Clim. Change 2, 182–185. https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate1354 (2012).

Saatchi, S. S. et al. Benchmark map of forest carbon stocks in tropical regions across three continents. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 9899–9904. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1019576108 (2011).

Saatchi, S. S., Houghton, R. A., Dos Santos AlvalÁ, R. C., Soares, J. V. & Yu, Y. Distribution of aboveground live biomass in the Amazon basin. Glob. Change Biol. 13, 816–837. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2007.01323.x (2007).

Muller-Landau, H. C., Wright, S. J., Calderon, O., Condit, R. & Hubbell, S. P. Interspecific variation in primary seed dispersal in a tropical forest. J. Ecol. 96, 653–667. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2745.2008.01399.x (2008).

Mendoza, I. et al. Does masting result in frugivore satiation? A test with Manilkara trees in French Guiana. J. Trop. Ecol. 31, 553–556. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266467415000425 (2015).

Kelly, D. The evolutionary ecology of mast seeding. Trends Ecol. Evol. 9, 465–470. https://doi.org/10.1016/0169-5347(94)90310-7 (1994).

Kelly, D. & Sork, V. L. Mast seeding in perennial plants: Why, how, where?. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 33, 427–447. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.33.020602.095433 (2002).

Johnson, M. O. et al. Variation in stem mortality rates determines patterns of above-ground biomass in Amazonian forests: Implications for dynamic global vegetation models. Glob. Change Biol. 22, 3996–4013 (2016).

Batista, A. P. B. et al. Caracterização estrutural em uma floresta de terra firme no estado do Amapá, Brasil. Pesq. flor. bras 35, 21–33 (2015).

Charles-Dominique, P. et al. Les mammiferes frugivores arboricoles nocturnes d’une foret guyanaise: Inter-relations plantes-animaux. La Terre et la Vie: Revue d’Ecologie Appliquée 35, 341–435 (1981).

de Oliveira, A. N. & do Amaral, I. L. ,. Florística e fitossociologia de uma floresta de vertente na Amazônia Central, Amazonas, Brasil. Acta Amazonica 34, 21–34 (2004).

Pereira, L. A., Pinto Sobrinho, F. D. A. & Costa Neto, S. V. D. Florística e estrutura de uma mata de terra firme na reserva de desenvolvimento sustentável rio Iratapuru, Amapá, Amazônia Oriental, Brasil. (2011).

Pereira, L. A., Sena, K. S., dos Santos, M. R. & Neto, S. V. C. Aspectos florísticos da FLONA do Amapá e sua importância na conservação da biodiversidade. Revista Brasileira de Biociências 5, 693–695 (2007).

Sabatier, D. Saisonnalité et déterminisme du pic de fructification en forêt guyanaise. Revue d’Ecologie (Terrre et Vie) 40, 89–320 (1985).

ter Steege, H. et al. An analysis of the floristic composition and diversity of Amazonian forests including those of the Guiana Shield. J. Trop. Ecol. 16, 801–828 (2000).

Hanya, G. et al. Seasonality in fruit availability affects frugivorous primate biomass and species richness. Ecography 34, 1009–1017. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0587.2010.06775.x (2011).

Situmorang, J. P. & Sugianto, S. Estimation of carbon stock stands using EVI and NDVI vegetation index in production forest of Lembah Seulawah Sub-District, Aceh Indonesia. Aceh Int. J. Sci. Technol. 5 (2016).

Asner, G. P. et al. Airborne laser-guided imaging spectroscopy to map forest trait diversity and guide conservation. Science 355, 385–389. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaj1987 (2017).

Bhardwaj, D., Banday, M., Pala, N. A. & Rajput, B. S. Variation of biomass and carbon pool with NDVI and altitude in sub-tropical forests of northwestern Himalaya. Environ. Monit. Assess. 188, 635 (2016).

Dubayah, R. O. et al. Estimation of tropical forest height and biomass dynamics using lidar remote sensing at La Selva, Costa Rica. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. https://doi.org/10.1029/2009JG000933 (2010).

Holly, K. G., Sandra, B., John, O. N. & Jonathan, A. F. Monitoring and estimating tropical forest carbon stocks: Making REDD a reality. Environ. Res. Lett. 2, 045023 (2007).

Asner, G. P. et al. High-resolution forest carbon stocks and emissions in the Amazon. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 107, 16738–16742 (2010).

Magnusson, W. et al. Biodiversidade e monitoramento ambiental integrado (Biodiversity and Integrated Environmental Monitoring). 335 (PPBio INPA, 2013).

Kottek, M., Grieser, J., Beck, C., Rudolf, B. & Rubel, F. World map of the Koppen–Geiger climate classification updated. Meteorol. Z. 15, 259–263. https://doi.org/10.1127/0941-2948/2006/0130 (2006).

ANA. Sistema de Monitoramento Hidrológico (Hydrological Monitoring System). Agência Nacional de Águas[[nl]]National Water Agency. http://www.hidroweb.ana.gov.br, 2016).

ICMBio. Vol. I (ed MINISTÉRIO DO MEIO AMBIENTE) 222 (Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade, Macapá, Amapá, 2014).

Eswaran, H., Ahrens, R., Rice, T. J. & Stewart, B. A. Soil Classification: A Global Desk Reference. (CRC Press, Boca Raton, 2002).

Dutech, C., Maggia, L. & Joly, H. I. Chloroplast diversity in Vouacapoua americana (Caesalpiniaceae), a neotropical forest tree. Mol. Ecol. 9, 1427–1432. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-294x.2000.01027.x (2000).

ter Steege, H. et al. Hyperdominance in the Amazonian Tree Flora. Science https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1243092 (2013).

Kido, T., Taniguchi, M. & Baba, K. Diterpenoids from Amazonian crude drug of Fabaceae. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 51, 207–208. https://doi.org/10.1248/cpb.51.207 (2003).

Maurya, R., Ravi, M., Singh, S. & Yadav, P. P. A review on cassane and norcassane diterpenes and their pharmacological studies. Fitoterapia 83, 272–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fitote.2011.12.007 (2012).

Alves, J. C. Z. O. & Miranda, I. D. S. Análise da estrutura de comunidades arbóreas de uma floresta amazônica de Terra Firme aplicada ao manejo florestal. Acta Amazonica 38, 657–666 (2008).

Forget, P. M., Mercier, F. & Collinet, F. Spatial patterns of two rodent-dispersed rain forest trees Carapa procera (Meliaceae) and Vouacapoua americana (Caesalpiniaceae) at Paracou, French Guiana. J. Trop. Ecol. 15, 301–313. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0266467499000838 (1999).

Forget, P.-M. Ten-year seedling dynamics in Vouacapoua americana in French Guiana: A hypothesis. Biotropica 29, 124–126 (1997).

Forget, P. M. Recruitment pattern of Vouacapoua-Americana (Caesalpiniaceae), a rodent-dispersed tree specie in French-Guiana. Biotropica 26, 408–419. https://doi.org/10.2307/2389235 (1994).

Forget, P. M. Effect of microhabitat on seed fate and seedling performance in two rodent-dispersed tree species in rain forest in French Guiana. J. Ecol. 85, 693–703. https://doi.org/10.2307/2960539 (1997).

Zhang, S. Y. & Wang, L. X. Comparison of 3 fruit census methods in French-Guiana. J. Trop. Ecol. 11, 281–294 (1995).

Stevenson, P. R. The relationship between fruit production and primate abundance in Neotropical communities. Biol. J. Lin. Soc. 72, 161–178. https://doi.org/10.1006/bijl.2000.049 (2001).

Norris, D., Rodriguez Chuma, V. J. U., Arevalo-Sandi, A. R., Landazuri Paredes, O. S. & Peres, C. A. Too rare for non-timber resource harvest? Meso-scale composition and distribution of arborescent palms in an Amazonian sustainable-use forest. For. Ecol. Manag. 377, 182–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2016.07.008 (2016).

Paredes, O. S. L., Norris, D., Oliveira, T. G. D. & Michalski, F. Water availability not fruitfall modulates the dry season distribution of frugivorous terrestrial vertebrates in a lowland Amazon forest. PLoS ONE 12, e0174049. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0174049 (2017).

Magnusson, W. E. et al. RAPELD: A modification of the Gentry method for biodiversity surveys in long-term ecological research sites. Biota. Neotrop. 5, 19–24. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1676-06032005000300002 (2005).

Norris, D., Fortin, M.-J. & Magnusson, W. E. Towards monitoring biodiversity in Amazonian forests: How regular samples capture meso-scale altitudinal variation in 25 km(2) plots. PLoS ONE https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0106150 (2014).

The Angiosperm Phylogeny Group. An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG III. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 161, 105–121. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8339.2009.00996.x (2009).

Guisan, A. & Zimmermann, N. E. Predictive habitat distribution models in ecology. Ecol. Model. 135, 147–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3800(00)00354-9 (2000).

Platts, P. J., McClean, C. J., Lovett, J. C. & Marchant, R. Predicting tree distributions in an East African biodiversity hotspot: Model selection, data bias and envelope uncertainty. Ecol. Model. 218, 121–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2008.06.028 (2008).

Camarero, J. J., Albuixech, J., López-Lozano, R., Casterad, M. A. & Montserrat-Martí, G. An increase in canopy cover leads to masting in Quercus ilex. Trees 24, 909–918. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00468-010-0462-5 (2010).

Fernández-Martínez, M., Garbulsky, M., Peñuelas, J., Peguero, G. & Espelta, J. M. Temporal trends in the enhanced vegetation index and spring weather predict seed production in Mediterranean oaks. Plant Ecol. 216, 1061. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11258-015-0489-1 (2015).

Fortin, M.-J. & Dale, M. R. T. Spatial Analysis: A Guide for Ecologists. 365 (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2005).

Hastie, T. J. & Tibshirani, R. J. Generalized Additive Models. Vol. 43 (CRC Press, Boca Raton, 1990).

Wood, S. Generalized Additive Models: An Introduction with R. (CRC Press, Boca Raton, 2006).

Wood, S. N. & Augustin, N. H. GAMs with integrated model selection using penalized regression splines and applications to environmental modelling. Ecol. Model. 157, 157–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3800(02)00193-X (2002).

R: A language and environment for statistical computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/ (2016).

Burnham, K. P. & Anderson, D. R. Model Selection and Multi-model Inference: A Practical Information-Theoretic Approach. (Springer, New York, 2002).

Pebesma, E. J. Multivariable geostatistics in S: The gstat package. Comput. Geosci. 30, 683–691. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cageo.2004.03.012 (2004).

Liaw, A. & Wiener, M. Classification and regression by randomForest. R News 2, 18–22 (2002).

e1071: Misc Functions of the Department of Statistics, Probability Theory Group v. 1.6-8 (2017).

Acknowledgements

The Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade (ICMBio) and the Federal University of Amapá (UNIFAP) provided logistical support. We thank IBAMA for authorization to conduct research in ANF (IBAMA/SISBIO permit 47859-1). We thank Patrick Cantuária and Tonny Medeiros from HAMAB-IEPA for fruit identification. We thank the Brazilian Long-term Biodiversity Monitoring Program (PPBio) for providing the grid system used during field activities. We thank Érico Emed Kauano and Sueli Gomes Pontes dos Santos for logistical assistance during the field campaigns. We thank Omar Stalin Landázuri Paredes, Yuri Breno da Silva e Silva, Alexander Roldan Arévalo Sandi and Edielza Aline dos Santos Ribeiro for their help during data collection. We are deeply indebted to Cremilson and Cledinaldo Alves Marques for their dedication, commitment and assistance during fieldwork. We are grateful to the editor and three anonymous reviewers whose comments improved previous versions of the text.

Author information

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chuma, V.J.U.R., Norris, D. Contribution of Vouacapoua americana fruit-fall to the release of biomass in a lowland Amazon forest. Sci Rep 11, 4302 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-83803-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-83803-y

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.