Abstract

Alterations in brain cholesterol homeostasis in midlife are correlated with a higher risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease (AD). However, global cholesterol-lowering therapies have yielded mixed results when it comes to slowing down or preventing cognitive decline in AD. We used the transgenic mouse model Cyp27Tg, with systemically high levels of 27-hydroxycholesterol (27-OH) to examine long-term potentiation (LTP) in the hippocampal CA1 region, combined with dendritic spine reconstruction of CA1 pyramidal neurons to detect morphological and functional synaptic alterations induced by 27-OH high levels. Our results show that elevated 27-OH levels lead to enhanced LTP in the Schaffer collateral-CA1 synapses. This increase is correlated with abnormally large dendritic spines in the stratum radiatum. Using immunohistochemistry for synaptopodin (actin-binding protein involved in the recruitment of the spine apparatus), we found a significantly higher density of synaptopodin-positive puncta in CA1 in Cyp27Tg mice. We hypothesize that high 27-OH levels alter synaptic potentiation and could lead to dysfunction of fine-tuned processing of information in hippocampal circuits resulting in cognitive impairment. We suggest that these alterations could be detrimental for synaptic function and cognition later in life, representing a potential mechanism by which hypercholesterolemia could lead to alterations in memory function in neurodegenerative diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Alterations in brain cholesterol homeostasis have been correlated to neurodegeneration in numerous studies1,2,3,4,5. In particular, hypercholesterolemia in mid-life is considered as the main non-genetic risk factor for developing Alzheimer’s disease (AD) later in life6,7,8,9,10. Despite numerous discoveries in AD pathophysiology, the identification of strategies that can modify the onset and progression of AD remains a challenge, and therapies aiming to lower cholesterol in AD patients have not resulted in clear improvements in cognition11. Moreover, the mechanisms triggered by brain cholesterol homeostasis alterations that drive neurodegeneration remain unclear. In the brain, cholesterol is synthesized entirely in situ by astrocytes, and peripheral cholesterol does not cross the blood–brain barrier (BBB) under physiological conditions12. However, oxysterols, which are oxidized cholesterol metabolites, can cross the BBB by diffusion and influence brain cholesterol synthesis12,13,14,15,16.

27-hydroxycholesterol (27-OH), which is the most common oxysterol in the body, is produced in the periphery by the enzyme sterol 27-hydroxylase (Cyp27A1) and has a net influx into the brain driven by a concentration gradient14,17. Since 27-OH levels in the body are proportional to the cholesterol content in the blood, hypercholesterolemia leads to high 27-OH levels in the brain, where it can mediate negative effects on neuronal physiology11,18,19,20,21. We recently described that, in young Cyp27Tg mice (Cyp27A1-overexpressing mouse model), high levels of 27-OH downregulate the postsynaptic protein PSD-95 levels in the hippocampus and cause morphological alterations in neuronal structure and dendritic spine (for simplicity, spine) density in CA1 pyramidal neurons22.

Spines of pyramidal cells, the most common cell type in the cerebral cortex (including the hippocampus), are the main postsynaptic targets of excitatory synapses and their function is crucial for memory, learning, and cognition23,24,25. It is generally assumed that one spine establishes one excitatory glutamatergic synapse26. Therefore, the number of spines indicates the number of excitatory inputs that pyramidal cells receive. Moreover, it has been shown that spine volume correlates with the postsynaptic density area, as well as the number of presynaptic vesicles, and postsynaptic receptors27,28,29. Also, the length of the spine neck is related to its biochemical and electrical properties30,31. Consequently, alterations in spine density and morphology could alter the neuronal connectivity and induce circuit malfunction. Besides, a large number of alterations in spine microanatomy have been linked to AD and other neurodegenerative diseases32,33,34,35,36.

To test the functional effects of elevated 27-OH levels on hippocampal synaptic plasticity, we used a paradigm of long-term potentiation (LTP) in the CA1 region of the hippocampus in young Cyp27Tg mice. We found that elevated levels of 27-OH led to an increase in the level of hippocampal LTP, as evaluated by the field excitatory postsynaptic potentials (fEPSPs). Using intracellular injections with Lucifer Yellow (LY) and confocal microscopy, we reconstructed 3D spines in both, basal (stratum oriens) and apical (stratum radiatum) dendrites from CA1 pyramidal neurons. Our results show that spines from the apical dendritic tree are larger in Cyp27Tg compared with wild-type (WT) mice, but no changes were found in the stratum oriens. Although we did not find changes in glutamatergic receptor levels in the hippocampus, we found increased levels of synaptopodin puncta in the stratum radiatum of Cyp27Tg mice by immunohistochemistry. Collectively, our results show elevated levels of 27-OH in the brain affecting LTP, based on the alterations of the size of spines and their synaptopodin content at the early stages of postnatal development.

Results

27-OH increases LTP in Cyp27Tg mice

To determine the effect of 27-OH overexpression on synaptic plasticity, we measured LTP in the CA1 region of the hippocampus of Cyp27Tg mice. For this purpose, evoked postsynaptic excitatory potentials were monitored through extracellular field recordings in the Schaffer collateral (SC)–CA1 pyramidal pathway. Stable evoked baseline activity was recorded for 30 min prior to the delivery of a theta-burst (Ø-burst) stimulation to induce LTP (Fig. 1). Cyp27Tg hippocampal slices showed a significantly higher magnitude of LTP when compared to hippocampal slices from WT animals (Fig. 1C; Cyp27Tg: 2.01 ± 0.17, n = 5 vs. WT: 1.54 ± 0.09, n = 5; *p = 0.03; unpaired Mann–Whitney test). In addition, Cohen's d was calculated to show the effect size (d = 1.47). The post-tetanic potentiation, measured as the average response during the first 5 min after delivering the stimulation, was not significantly different between the Cyp27Tg and WT mice (Cyp27Tg: 2.3 ± 0.07, n = 5; p = 0.16 vs. WT: 2.05 ± 0.11, n = 5; unpaired Mann–Whitney test). Additionally, the analysis of the input–output relationships recorded prior to LTP recordings showed no significant differences in basal synaptic transmission between WT and Cyp27Tg mice (Supplementary Fig. 1A; Two-way repeated measures ANOVA (F(1,8) = 0.87, p = 0.38). The assessment of the paired pulse ratio using 20, 40 or 60 ms of interstimulus interval showed no significant differences between genotypes at baseline (Two-way RM ANOVA F(1,4) = 0.0004, p= 0.98) and LTP was not associated to changes in the paired pulse ratio at the tested interstimulus intervals in WT (Supplementary Fig. 1A, Two-way RM ANOVA F(1,2) = 0.06, p = 0.82) or Cyp27Tg mice (Two-way RM ANOVA F(1,2) = 4.11, p = 0.18). This result strongly suggests that the expression of LTP in the Cyp27Tg mice involves post-synaptic mechanisms similar to what is observed in WT; however, further detailed electrophysiological characterization would be necessary to fully confirm this observation.

Altered Shaffer collateral-CA1 Long-term Potentiation (LTP) in Cyp27Tg mice. (A) Representative fEPSP traces before Ø-burst (gray traces) and 60 min after (black and turquoise traces). (B) Time-course of changes in field EPSP (fEPSP) slopes after induction of LTP show an increase in the magnitude of LTP induced by theta-burst (Ø-burst) stimulation in Cyp27Tg mice compared to WT hippocampal mouse slices. (C) Cyp27Tg mice (n = 5 slices/4 mice) showed significantly enhanced LTP compared to WT (n = 5 slices/3 mice) measured 55 to 60 min after Ø-burst relative to baseline; *p = 0.03 by unpaired Mann–Whitney test. Data are represented as the mean ± S.E.M.

High 27-OH does not modify expression levels of NMDARs and AMPARs (GluR1/GluA1 and GluR2/GluA2) in the hippocampus

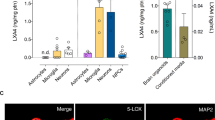

We performed immunoblotting analyses of the glutamate receptor N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunits (NMDARs) and receptor subunits 1 and 2 (GluR1/GluA1 and GluR2/GluA2) of the 2 α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid receptors (AMPARs), in the hippocampus of Cyp27Tg and WT mice and no overt changes were found between groups (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. 2). Cyp27Tg mice did not differ from WT mice regarding the levels of NMDAR-1 in the hippocampus (93.25 ± 8.61 vs. 100 ± 4.34, respectively) (p = 0.55; n = 4–5; unpaired Mann–Whitney test; Fig. 2A). Moreover, no differences were found between Cyp27Tg and WT mice when we compared protein levels for NMDAR-2B (Cyp27Tg, 100 ± 16.39; WT, 100 ± 11.26; p = 0.9; n = 4–5; unpaired Mann–Whitney test; Fig. 2B), NMDAR-2A (Cyp27Tg, 92.78 ± 6.67; WT, 100 ± 4.58; p = 0.55; n = 4–5; unpaired Mann–Whitney test; Fig. 2C) and phosphorylated NMDAR-2A (Cyp27Tg, 94.96 ± 5.48; WT, 100 ± 13.11; p = 0.73; n = 4–5; unpaired Mann–Whitney test; Fig. 2D) In parallel with possible differences in NMDARs hippocampal protein levels in Cyp27Tg compared to WT mice, we evaluated protein levels of AMPA-R. Expression levels of GluR1/GluA1 and GluR2/GluA2 subunits in the hippocampus were similar in Cyp27Tg and WT animals (GluR1/GluA1: Cyp27Tg; 90.89 ± 6.30; WT; 100 ± 3.67; p = 0.73, n = 4–5; unpaired Mann–Whitney test; Fig. 2E and GluR2/GluA2: Cyp27Tg; 90.90 ± 5.82; WT; 100 ± 3.48; p = 0.41; n = 4–5; unpaired Mann–Whitney test; Fig. 2F).

No changes in NMDARs and AMPARs hippocampal protein levels under high levels of 27-OH. (G) Western blot and (A−F) densitometry analysis showing the proteins levels (normalized to GAPDH) of (A) NMDAR-1, (B) NMDAR-2B, (C) NMDAR-2A, (D) pNMDAR-2A, (E) GluR1/GluA1 and (F) GluR2/GluA2 in the hippocampus of Cyp27Tg (n = 4) compared to WT mice (n = 5). Unpaired Mann–Whitney test was employed in each comparison to compare averages. All data are represented as mean ± SEM.

Dendritic spines from CA1 pyramidal neurons are larger in the stratum radiatum in Cyp27Tg mice

To examine whether high levels of 27-OH could affect spine morphology from CA1 pyramidal neurons in Cyp27Tg mice, we performed a detailed 3D reconstruction analysis (Fig. 3). For this purpose, cells were labeled by intracellular injections in brain slices from 7- to 8-week-old WT and Cyp27Tg mice. A total of 182 pyramidal neurons from WT mice and 178 from Cyp27Tg mice were injected individually with LY in the CA1 region from the hippocampus (Fig. 3), and 3D images were computed by confocal microscopy. A detailed dendritic spine morphology analysis of the CA1 hippocampal subfield from Cyp27Tg mice was performed. Both basal dendrites (stratum oriens) and apical dendrites (stratum radiatum) were included in the analysis. For the statistical analysis, 4–5 animals per group were analyzed.

(A) Hippocampal panoramic view taken from a Cyp27Tg mouse intracellularly injected in CA1 with LY (green) and stained with DAPI (blue). (B) Higher magnification of A showing single CA1 pyramidal neurons individually injected with LY. (C−J) Representative pictures (63X oil; pixel size 0.057 × 0.057; z-step 0.14) of basal (Or; stratum oriens) dendrites (C−F) and apical (Rad; stratum radiatum) dendrites (G−J) from WT (C, E, G, I) and Cyp27Tg (D, F, H, J) mice. (K−N) 3D reconstruction of the complete spine morphology. (K) Dendritic segment from a CA1 pyramidal neuron in the stratum oriens from a WT mouse. For each stack of images, a solid surface was created to match the dendritic shaft (L). Various intensity threshold surfaces were then created (M), and the solid surface that exactly matched the contours of the dendritic spine volume was then selected for each dendritic spine (N). Scale bar shown in N indicates 300 µm in A, 40 µm in B, 10 µm in C−J and 5 µm in K−N.

Intracellular injections and 3D spine reconstruction.

In the stratum oriens, spine morphology was measured by assessing a total of 4253 spines in WT mice and 2758 spines in Cyp27Tg mice. No statistically significant difference was found in the average spine length between Cyp27Tg (0.91 ± 0.04 μm; n = 19 dendrites) and WT mice (0.89 ± 0.02 μm; n = 25 dendrites; unpaired Mann Whitney test; p > 0.05; Fig. 4A). Likewise, when analyzing spine length as a function of the distance from the soma, no statistical significance was found (Two-way ANOVA, p > 0.05; F = 1.37; Fig. 4B). However, a significant difference was found between groups when we analyzed spine length using frequency distribution (Kolmogorov–Smirnov, p < 0.0001; Fig. 4C). Differences in spine volume did not show statistical significance between groups when it was analyzed as an average (WT, 0.15 ± 0.01 μm3; n = 25 dendrites; Cyp27Tg, 0.17 ± 0.07 μm3; n = 19 dendrites; unpaired Mann Whitney test; p > 0.05; Fig. 4D); as a function of the distance from the soma (Two-way ANOVA, p > 0.05; F = 2.37; Fig. 4E); or using frequency distribution (Kolmogorov–Smirnov, p > 0.05; Fig. 4F).

Dendritic spines from CA1 apical dendrites are larger in Cyp27Tg than in WT mice. Comparative morphometric analysis of spine length (A−C, G−I) and spine volume (D−F,J−L) for CA1 LY-injected pyramidal neurons in WT and Cyp27Tg mice for both basal (A−F) and apical (G–L) dendrites. Data are shown as average per dendrite (A,D,G and J; Unpaired Mann–Whitney test), as a function of the distance from the soma (B,E,H and K, Two-way ANOVA repeated measures followed by a post-hoc multiple Bonferroni test) and frequency distribution (C,F,I and L; Kolmogorov–Smirnov test). All data are represented as mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001.

In the stratum radiatum, spine morphology was examined in apical branches protruding from the main apical trunk. These dendrites were located up to 300 µm from the stratum pyramidale (cell body layer). Dendrites located in the stratum lacunosum-moleculare were not included in the analysis. In the stratum radiatum, the spine morphology was measured by assessing a total of 2343 spines in WT mice and 2093 spines in Cyp27Tg mice. A significantly higher average dendritic spine length was found in Cyp27Tg (1.17 ± 0.04 μm; n = 20 dendrites) compared with WT mice (0.99 ± 0.02 μm; n = 20 dendrites; unpaired Mann Whitney test; p = 0.0028; Fig. 4G). Moreover, a statistically significant difference was found between groups regarding dendritic spine length as a function of the distance from the soma (Two-way ANOVA, p = 0.014; F = 2.56; p < 0.05, Bonferroni post-hoc test; Fig. 4H) and when using frequency distribution analysis (Kolmogorov–Smirnov, p < 0.0001; Fig. 4I). When we analyzed spine volume, a significantly higher average value was found in Cyp27Tg (0.19 ± 0.01 μm3; n = 20 dendrites) compared with WT mice (0.15 ± 0.01 μm3; n = 20 dendrites; unpaired Mann Whitney test; p = 0.04; Fig. 4J) and this was also the case when frequency distribution analysis was used (Kolmogorov–Smirnov, p < 0.0001; Fig. 4L). However, no statistical significance was found in the analysis of spine volume as a function of the distance from the soma (Two-way ANOVA, p > 0.05; F = 0.73; Fig. 4K).

High 27-OH levels increase the number of synaptopodin immunoreactive puncta in stratum radiatum

The numbers of synaptopodin immunoreactive (ir) puncta were analyzed in the stratum radiatum from CA1 region in WT and Cyp27Tg mice (Fig. 5). This analysis was performed at two different distances from the pyramidal layer: 20–80 μm and 100–160 μm (Fig. 5B, C). In the stratum radiatum, we found a significantly higher number of synaptopodin-ir puncta in Cyp27Tg (132.1 ± 2.73 number of puncta/1000 μm3) than in WT mice (113.3 ± 2.32 number of puncta/1000 μm3; unpaired Mann Whitney test; p < 0.0001; n = 4–5 mice; Fig. 5E). In the distal stratum radiatum, 15% more synaptopodin-ir puncta were found in Cyp27Tg (159.5 ± 3.38 number of puncta/1000 μm3) than in WT mice (135.7 ± 2.3 number of puncta/1000 μm3; unpaired Mann Whitney test; p < 0.0001; n = 4–5 mice; Fig. 5F).

Cyp27Tg mice showed increased numbers of synaptopodin-ir puncta in the stratum radiatum. (A) Panoramic view of the hippocampus from a WT mouse stained with anti-synaptopodin antibody. (B, C) Representative pictures of the CA1 region in WT (B) and Cyp27Tg (C) mice, respectively. White squares represent the regions analyzed with confocal microscopy. Two different distances from the pyramidal layer were analyzed: 20−80 and 60−120 μm (distal stratum radiatum). (D) Photomicrograph in CA1 region from a WT mouse showing the synaptopodin-ir puncta distribution. (E−F) Comparative analysis showing scatter plots (GraphPad Prism 5.0) of the number of synaptopodin-ir puncta/ μm3 for the (E) stratum radiatum and (F) distal stratum radiatum for Cyp27Tg compared to WT mice. Unpaired Mann–Whitney test was employed to compare groups. s.r., stratum radiatum; s.o., stratum oriens; p.l., pyramidal layer. All data are represented as mean ± SEM. Scale bar shown in A indicates 500 μm in A, 100 μm in B and C, and 10 μm in D.

Discussion

The present study aimed to test whether the alterations in neuronal morphology observed previously in CA1 of Cyp27Tg mice22 would correlate with synaptic plasticity dysfunction in the hippocampus. Our previous results show lower spine density in both apical and basal dendrites in Cyp27Tg compared with WT animals. However, the lower neuronal complexity was observed exclusively in the case of the basal dendritic tree in Cyp27Tg animals22. To address this aim, we performed LTP in brain slices of young adult Cyp27Tg mice and found an altered LTP response compared to WT mice. We found that LTP was increased in Cyp27Tg mice, with a steeper slope for the rise-time of fEPSPs 60 min after the theta-burst stimulation.

Our western blot results show that there was no difference in overall expression levels of NMDARs and AMPARs, and no increase in phosphorylation of the NMDAR-2A in Cyp27Tg mice compared to WT. Thus, neither the overall number of these receptors nor the sensitivity of the NMDA receptors37,38 seems to explain the increase in LTP. Thus, we decided to examine the microanatomy of the circuit.

Since the excitatory inputs that pyramidal cells receive are related to their number of spines, abundance and morphology39,40,41, we decided to analyze the morphological features of spines from both basal (stratum oriens) and apical (stratum radiatum) dendritic trees in CA1 pyramidal neurons. We found that globally, spines from apical dendrites were larger in Cyp27Tg mice than in WT counterparts. However, no differences were found in basal dendritic trees, suggesting that cortical circuits in the stratum radiatum and the stratum oriens might be affected differently by high levels of 27-OH. Distinct alterations in spine morphology between the CA1 strata in AD models have been previously described, suggesting this feature as a possible common hallmark in AD models36. Significant differences were found regarding spine volume and length, indicating that the spines from the apical dendritic tree, which receive input from the Schaffer collaterals, undergo both structural and functional plastic alterations.

Moreover, a detailed analysis of the morphological parameters as a function of the distance from the soma demonstrates that in apical dendrites the difference in spine length was only found up to 40 µm from the soma. It is well established that spine density and spine morphology along the dendrite is dependent on the distance from the cell body42, suggesting that synaptic input information processing varies depending on the location of the synaptic inputs on the dendrite. Since these plastic changes did not involve the upregulation of glutamate receptors, this led us to speculate whether the increase in volume and length of spines might be due to increased docking of glutamate receptors on the postsynaptic membrane.

Postsynaptic proteins are crucial structures of spines and are essential in memory acquisition and consolidation. In particular, PSD-95 and synaptopodin are important for learning and the plastic changes observed in LTP43,44 and also for synaptogenesis during development45,46. Previously, we reported lower PSD-95 levels in Cyp27Tg22; however, PSD-95 regulation is very dynamic47 and can be altered by the LTP paradigm44. Therefore, an enhancement in LTP response cannot be explained by PSD-95 downregulation. Moreover, previous work has reported an enhanced LTP response in the absence of PSD-9548. Synaptopodin, on the other hand, can control the expression and docking of glutamate receptors in response to several stimuli49. It can also affect the morphology of spines50 and is an essential structure of the LTP apparatus51. It has been shown previously that synaptopodin mRNA and/or protein expression is highly regulated under different conditions in podocytes and in various neuronal types52,53,54. Other mechanisms can alter the LTP response such as the GABAergic system55; however, synaptopodin expression is mostly restricted to excitatory pyramidal neurons46. In addition, behavioral experiments in old Cyp27Tg mice have not suggested any alterations in the GABAergic system20.

By immunostaining for synaptopodin in CA1, we found a significantly higher number of positive puncta in stratum radiatum of the pyramidal layer of Cyp27Tg compared to WT mice, which correlates with the microanatomical characterization discussed above. This implies that synaptopodin is specifically upregulated in spines in response to 27-OH leading to their enlargement. With larger spines in the apical dendritic tree, Cyp27Tg pyramidal neurons are more likely to potentiate the responses to glutamatergic input than WT are. Synaptopodin is an essential component of subpopulations of spines of hippocampal cells, in which it is critical for the recruitment of the spine apparatus which is involved in spine calcium kinetics and is required for the dynamic reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton in spine plasticity46,51,56,57,58.

Since 27-OH is present prenatally in Cyp27Tg mice, it is possible that regulatory mechanisms that are important for LTP have been depleted or abolished, as shown by the higher magnitude of the LTP response in these mice. In this regard, we found that elevated levels of 27-OH in the brain induce alterations in synaptic plasticity of CA1 pyramidal neurons, supported by upregulation of synaptopodin-positive puncta. We previously reported that high levels of 27-OH downregulate microRNA-124 (miR-124) expression in the hippocampus22 and other studies have found that the absence of miR-124 induces overexpression of synaptopodin in the spinal cord59. It is therefore, possible that the synaptopodin upregulation could be a consequence of the downregulation of miR-124 via an effect of 27-OH on spines, inducing an aberrant response to synaptic input from the Schaffer collaterals. An additional regulator of synaptopodin expression is aromatase, whose expression has been shown to decrease in response to calcium transients together with synaptopodin60. Therefore, it is possible that the effect of 27-OH on synaptopodin can be mediated by a cascade involving aromatase, although this correlation remains to be described. Moreover, other regulators of spine formation such as estrogen61 have been reported to be modulated by 27-OH62, however, the direct relationship of 27-OH and estrogen signaling in synaptogenesis is still uncharacterized. Similarly, the REST complex, also called RE1 silencing transcription factor, can lead to decrease dendritic spine size, as seen in genetic models of Down syndrome63. Since we have previously reported that 27-OH alters normal REST expression in primary neurons22, it is possible that REST can be another target linking 27-OH with dendritic spine alterations seen in this work.

We previously reported that high levels of 27-OH downregulate PSD-95 and decrease spine density in pyramidal neurons in the hippocampus22. We hypothesized that decreased PSD-95 levels would appear together with decreased glutamate receptors in the postsynaptic element and would alter the LTP function in the hippocampus. However, glutamate transporter levels were not significantly changed, whereas the LTP response was altered in Cyp7Tg mice. In the present study, we found that spine volume is increased, as well as the number of synaptopodin puncta in the stratum radiatum of the hippocampus. Overexpression of synaptopodin can lead to increased spine size and modify the CA1 LTP response52,57. Since synaptopodin is an essential regulator of the spine apparatus64, we propose that the specific upregulation of synaptopodin in spines in response to 27-OH may explain the spine enlargement. This could represent a compensatory mechanism in response to the decrease in PSD-95 and SHANK levels previously reported by our group20. Compared to WT, Cyp27Tg pyramidal neurons have larger spines in the apical dendritic tree and consequently are more likely to potentiate the responses to glutamatergic input. It is well established that LTP induces spine-remodeling and an increase in spine size65,66,67,68,69, but it is also clear that larger, mature spines can contain more of the signaling proteins necessary for LTP induction and may therefore be more easily potentiated70,71.

Consistent with this, we found that elevated levels of 27-OH in the brain induce increased LTP in CA1 pyramidal neurons. An enhanced LTP has previously been observed in other models for neurodegeneration such as AD72 and Nasu-Hakola disease73, which are characterized by alterations in cognition and learning. Although LTP at specific synapses is unequivocally associated with memory, a sustained increase in stimulation can lead to activation of cell death cascades74. However, increased activity and continuous release of glutamate have been shown to precede neurodegeneration75,76,77,78 and recent work suggests that an imbalance between homeostatic response and specific synaptic plasticity such as LTP may be an underlying cause of AD79. A lower LTP response is often seen in AD models80, but we must point out that not all AD models have reduced LTP. The APPswe/ind mice, which have a double APP mutation, have increased LTP with clear signs of synaptic excitability and increased maximum amplitude of evoked EPSCs at 20 weeks of age81. The alterations in LTP observed in our model shows an aberrant response to the high frequency stimulation of Schaffer collaterals in CA1, including an exacerbated sustained potentiaton of fEPSC. This is evidence of a deviation from the physiological LTP response, rather than an enhancement and it is most likely detrimental for hippocampal function, leading to the cognitive disorders seen in older Cyp27Tg mice20.

High 27-OH levels in the brain arise from a peripheral imbalance in cholesterol metabolism, which is related to non-genetic risk factors for neurodegeneration and cardiovascular disease82,83. In the present study, we found that despite the peripheral origin of 27-OH, its high levels can directly affect basic mechanisms of memory in the brain by altering the microanatomy of certain pyramidal neurons in the hippocampus and their response to synaptic input. Given its ubiquitous abundance in the brain, once it is elevated84, 27-OH will most likely affect multiple cell types and regions that undergo plasticity. Further research is required to fully understand all the detrimental mechanisms associated with elevated 27-OH in the central nervous system.

Methods

Animals

Cyp27Tg

We used a transgenic mouse model (Cyp27Tg) that overexpresses the enzyme Cyp27A121. Since Cyp27A1 converts cholesterol to 27-OH85, Cyp27Tg mice have 5–6 times higher levels of 27-OH than control mice (WT) in serum (283 ± 11 vs. 48 ± 2 ng/ml) and in the brain (3.5 ± 0.5 vs. 0.3 ± 0.0 ng/mg) throughout life20, but have normal brain cholesterol levels14. In addition, Cyp27Tg showed a deficit in cognition20. Age-matched WT littermates served as controls. The mice were fed normal chow and water provided ad libitum and housed in groups of four or five with a 12 h light/dark cycle. Only two- to four-month-old males were used.

For immunoblotting analyses, an additional cohort of Cyp27Tg (n = 4) and WT mice (n = 5) were sacrificed by decapitation. The brains were dissected and immediately frozen on dry ice and stored at –80 °C until processing. An entire right hippocampus per animal was included in the western blot analysis. For intracellular injections and immunohistochemistry, the animals were overdosed with sodium pentobarbitone intraperitoneally. They were then perfused intracardially with 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) and subsequently post-fixed in PFA for 24 h. The study was carry out in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines.

Electrophysiology

Male mice (2 to 4 months old; 4 WT and 3 Cyp27Tg) were decapitated after been deeply anesthetized with isoflurane. Then, the brain was dissected out and placed in ice-cold standard artificial CSF (aCSF; 130 mM NaCl, 24 mM NaHCO3, 10 mM glucose, 1.25 mM NaH2PO4, 3.5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2 and 2 mM CaCl2). 400 µm thick horizontal slices were prepared from the ventral hippocampus using a Leica VT1200S vibratome (Leica Microsystems). The slices were allowed to recover in an interface incubation chamber filled with 34 °C aCSF for 15–30 min and then left in the chamber that was allowed to cool down at room temperature. After a minimum recovery of 2 h, the slices were transferred to a submerged recording chamber with a perfusion rate of 2–3 ml per min with standard aCSF at 32 °C, constantly bubbled with carbogen gas (5% CO2, 95% O2).

LTP was examined in the Shaffer collaterals (SC)-CA1 pathway by evoking synaptic activity with an electrical stimulation using a bipolar concentric electrode (FHC Inc., USA) connected to an isolated current stimulator (Digitimer, UK) and recording field excitatory postsynaptic potentials (fEPSPs) using an extracellular recording pipette filled with regular aCSF. The recording electrode was placed around 50 to 100 µm from the pyramidal cell layer and the stimulation electrode was placed at the Schaffer collaterals at a distance of between 200 and 250 µm from the recording electrode. A stable fEPSP baseline response was collected by stimulation every 30 s for at least 30 min using 50–60% of the maximal response determined using a previously generated input–output curve. To induce LTP in the CA1 region, a protocol of theta-burst stimulation (Ø-burst) was used; a Ø-burst consisted of 2 trains with 10 bursts of 4 pulses at 100 Hz and bursts were delivered at 5 Hz. In some of the slices, a series of paired pulse facilitation experiments with inter-stimulus intervals of 10, 20 and 60 ms were performed after the baseline recording and 60 min after the induction of LTP. Responses were quantified by determining the slope of the linear rising phase of the fEPSP (between 10 and 70% before reaching the peak amplitude). The response was normalised to baseline response for each slice and the magnitude of LTP was determined by comparing the five-minute average of the fEPSP slope 60 min after the Ø-burst stimulation with the average of the last five minutes of the baseline recording.

Intracellular injections, reconstruction and 3D morphometric analysis

Coronal whole brain sections (150 μm) were obtained using a vibratome. The sections were prelabeled with 4,6 diamino-2-phenylindole (DAPI; Sigma, St Louis, MO). CA1 pyramidal neurons were then individually injected with LY by continuous current as previously described22. Imaging was performed with a Nikon Ti-E inverted point scanning confocal system with a 488 nm Argon laser and UV (405 nm). The fluorescence of DAPI and Alexa 488 was recorded through separate channels. We obtained image stacks of 10–100 image planes with a 20 × dry lens (NA, 0.75). No pixels were saturated within the spines. After acquisition, the stacks were analyzed with 3D image processing software — Imaris 9.1 (Bitplane AG, Zurich, Switzerland) by a person blinded to the experimental conditions.

Morphometric parameters of spines: The volume and the length of the spines were established blindly by semiautomatic reconstruction using the Filament tool from Imaris.

For the morphological analysis, an optimal sampling of the dendrites was performed. We selected exclusively the dendrites that were homogeneously infused to avoid differences in LY intensities due to experimental procedures. Briefly, several filaments were created for each stack of images, and the parameters were modified until the contours matched with the volume of the spines. The image of each dendrite was rotated in 3D and examined to ensure that the selected contour for each spine was appropriate. In addition, the spine volume and spine length were measured as a function of the distance from the soma. Concentric spheres of increasing 10 μm radii were created (Sholl analysis).

Immunoblotting analysis

Western blot analysis was carried out in tissue from the whole hippocampi as described previously22. 20 µg of total soluble protein from whole hippocampal lysates were loaded into acrylamide gels and separated using SDS-PAGE. After being transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Schleicher & Schuell, Germany), milk-blocked blots were incubated overnight with the following antibodies: anti-GluR1 (ab109450, rabbit monoclonal, 1:1000; Abcam, UK), anti-GluR2 (ab20673, rabbit polyclonal, 1:1000; Abcam, UK), anti-NMDAR1 (ab109182, rabbit monoclonal, 1:1000, Abcam, UK), anti-NMDAR-2A (ab124913, rabbit monoclonal, 1:1000; Abcam, UK), anti-phosphorylated-NMDAR-2A (Y1325, ab106590, rabbit polyclonal; Abcam, UK), anti-NMDAR-2B (ab28373, mouse monoclonal, 1:1000; Abcam, UK), and anti-GAPDH (ab8425, mouse polyclonal, 1:1000; Enzo, USA). Secondary incubation was carried out using anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IRDye infrared IgG antibodies (Li-Cor Biosciences, USA) at a 1:5000 dilution at room temperature. Immunoreactivity was detected using Odyssey CLx Imaging System (Li-Cor Biosciences, USA). The densitometric analyses of the immunoreactive bands were performed using Image Studio Lite ver. 5.2 (Li-Cor Biosciences, USA). Some immunoblots were stripped using Restore Western Blot Stripping buffer (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) at room temperature for 15 min and then blocked and re-blotted with other antibodies.

Immunofluorescence and synaptopodin-positive puncta quantification analysis

Free-floating coronal Sects. (50 μm) were used for single immunofluorescence. First, the slices were blocked for 1 h in PB (0.1 M) with 0.25% Triton X -100 and 3% normal goat serum (Vector Laboratories Inc., Burlingame, CA, USA). Then, the sections were incubated overnight with the primary antibody rabbit anti-synaptopodin (SE-19; S9442; Sigma; 1:500) at 4 °C and subsequently incubated for 2 h at room temperature with Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (A11012, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, 1:1000). Last, the sections were counterstained with DAPI (4, 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; Sigma, San Louis; MO; 1:80), mounted and coverslipped with ProLong Gold antifade reagent for immunofluorescence analysis (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). For synaptopodin immunostaining validation, double immunofluorescence was performed with synaptopodin (described above) and the presynaptic marker for the vesicular glutamate transporter 1 (VGLUT-1; AB5904, Millipore, Massachusetts, USA, 1:5000) antibodies (Supplementary Fig. 3). Free-floating sections were incubated overnight at 4 °C in a solution containing the primary antibodies, and then for 2 h at room temperature with biotinylated goat anti-guinea pig antibody for VGLUT-1 (1:200: Vector). After rinsing in PB, the sections were incubated for 2 h at room temperature with streptavidin coupled to Alexa fluor 488 (1:2,000, S-32354, Molecular Probes) and Alexa Fluor 594-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody. The sections were finally counterstained with DAPI, mounted and coverslipped with ProLong Gold antifade reagent for immunofluorescence analysis.

For synaptopodin-positive puncta quantification analysis, confocal microscopy was performed with a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal laser scanning system (Carl Zeiss Microscopy GmbH, Jena, Germany). The puncta were recorded with a 63 × objective (NA, 1.4) through separate channels (image resolution 1024 × 1024 pixels; Image size 58.67 μm × 58.67 μm). Z depth in every confocal stack was 0.14 μm. We scanned 9 image stacks from the stratum radiatum of the CA1 region from each section (two sections per animal). The stacks were taken at two different distances from the pyramidal layer: 20–80 μm and 100–160 μm (distal stratum radiatum). For the quantification of the synaptopodin-positive puncta, Image J software (a 3D object counting tool) was used. The image stacks were cropped to ensure that they were restricted to areas of fine neuropil. Synaptopodin fluorescence was automatically enhanced and then single-pixel background fluorescence was eliminated by de-speckling. The 3D object counting tool was then applied to collect data regarding the number and size of synaptopodin-ir punctate elements excluding those in contact with exclusion borders. To estimate density values, the number of synaptopodin-ir puncta was then normalized according to the tissue volume of each stack. To ensure impartiality, all the measurements were done blindly by the same investigator.

Statistical analysis

To test the overall effect, unpaired Mann–Whitney test was used to compare the averages. For spine morphology analysis, Two-way ANOVA repeated measures (P and F values + interaction are shown) followed by a post-hoc multiple Bonferroni test were used to compare values as a function of the distance from the soma. Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to perform frequency distribution analysis. Data values are expressed as mean ± SEM. In all cases, p < 0.05 was considered to be significant (* < 0.05, ** < 0.01, *** < 0.001, **** < 0.0001).

In addition, Cohen's d was calculated to test the effect size in the electrophysiological analysis. Cohen's d was obtained as the difference between the means divided by the pooled SD of both groups at baseline. Cohen's d can define effect sizes that are small (d = 0.2 to 0.49), medium (d = 0.5 to 0.79), and large (d ≥ 0.8).

Ethical approval

All experimental procedures were conducted following European relevant guidelines and regulations and were approved by the Swedish Board of Agriculture (ethical permits ID S33-13, extension 57-15 and 4884/2019).

References

Bai, F., Yuan, Y., Shi, Y. & Zhang, Z. Multiple genetic imaging study of the association between cholesterol metabolism and brain functional alterations in individuals with risk factors for Alzheimer’s disease. Oncotarget 7, 15315–15328. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.8100 (2016).

Bigini, P. et al. Neuropathologic and biochemical changes during disease progression in liver X receptor beta-/- mice, a model of adult neuron disease. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 69, 593–605. https://doi.org/10.1097/NEN.0b013e3181df20e1 (2010).

Boussicault, L. et al. CYP46A1, the rate-limiting enzyme for cholesterol degradation, is neuroprotective in Huntington’s disease. Brain 139, 953–970. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awv384 (2016).

Cacciatore, S. & Tenori, L. Brain cholesterol homeostasis in Wilson disease. Med. Hypotheses 81, 1127–1129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2013.10.018 (2013).

Cartocci, V. et al. Altered brain cholesterol/isoprenoid metabolism in a rat model of autism spectrum disorders. Neuroscience https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2017.12.053 (2018).

Kivipelto, M. Midlife vascular risk factors and Alzheimer’s disease in later life: longitudinal, population based study. BMJ 322, 1447–1451. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.322.7300.1447 (2001).

Kivipelto, M. & Solomon, A. Cholesterol as a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease—epidemiological evidence. Acta Neurol. Scand. 114, 50–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0404.2006.00685.x (2006).

Alzheimer’s Association. Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s Dement. 14(367–429), 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.001 (2018).

Morishima-Kawashima, M. & Ihara, Y. Alzheimer’s disease: beta-Amyloid protein and tau. J. Neurosci. Res. 70, 392–401. https://doi.org/10.1002/jnr.10355 (2002).

Jucker, M., Beyreuther, K., Haass, C., Nitsch, R. M. & Christen, Y. Alzheimer: 100 Years and Beyond (Springer, Berlin, 2006).

Loera-Valencia, R., Goikolea, J., Parrado-Fernandez, C., Merino-Serrais, P. & Maioli, S. Alterations in cholesterol metabolism as a risk factor for developing Alzheimer’s disease: potential novel targets for treatment. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 190, 104–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsbmb.2019.03.003 (2019).

Bjorkhem, I. et al. Cholesterol homeostasis in human brain: turnover of 24S-hydroxycholesterol and evidence for a cerebral origin of most of this oxysterol in the circulation. J. Lipid Res. 39, 1594–1600 (1998).

Bjorkhem, I., Lutjohann, D., Breuer, O., Sakinis, A. & Wennmalm, A. Importance of a novel oxidative mechanism for elimination of brain cholesterol. Turnover of cholesterol and 24(S)-hydroxycholesterol in rat brain as measured with 18O2 techniques in vivo and in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 30178–30184 (1997).

Ali, Z. et al. On the regulatory role of side-chain hydroxylated oxysterols in the brain. Lessons from CYP27A1 transgenic and Cyp27a1(-/-) mice. J. Lipid Res. 54, 1033–1043. https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.M034124 (2013).

Meaney, S., Bodin, K., Diczfalusy, U. & Björkhem, I. On the rate of translocation in vitro and kinetics in vivo of the major oxysterols in human circulation. J. Lipid Res. 43, 2130–2135. https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.m200293-jlr200 (2002).

Lutjohann, D. et al. Cholesterol homeostasis in human brain: evidence for an age-dependent flux of 24S-hydroxycholesterol from the brain into the circulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 9799–9804 (1996).

Meaney, S. et al. On the origin of the cholestenoic acids in human circulation. Steroids 68, 595–601. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0039-128x(03)00081-3 (2003).

Liu, Q. et al. Relationship between oxysterols and mild cognitive impairment in the elderly: a case–control study. Lipids Health Dis. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12944-016-0344-y (2016).

Heverin, M. et al. 27-Hydroxycholesterol mediates negative effects of dietary cholesterol on cognition in mice. Behav. Brain Res. 278, 356–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbr.2014.10.018 (2015).

Ismail, M. A. et al. 27-Hydroxycholesterol impairs neuronal glucose uptake through an IRAP/GLUT4 system dysregulation. J. Exp. Med. 214, 699–717. https://doi.org/10.1084/jem.20160534 (2017).

Meir, K. et al. Human sterol 27-hydroxylase (CYP27) overexpressor transgenic mouse model. Evidence against 27-hydroxycholesterol as a critical regulator of cholesterol homeostasis. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 34036–34041. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M201122200 (2002).

Merino-Serrais, P. et al. 27-hydroxycholesterol induces aberrant morphology and synaptic dysfunction in hippocampal neurons. Cereb Cortex 29, 429–446. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhy274 (2019).

Yuste, R. Dendritic spines and distributed circuits. Neuron 71, 772–781. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2011.07.024 (2011).

Spruston, N. Pyramidal neurons: dendritic structure and synaptic integration. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 206–221. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2286 (2008).

DeFelipe, J. The dendritic spine story: an intriguing process of discovery. Front. Neuroanat. 9, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnana.2015.00014 (2015).

Arellano, J. I., Espinosa, A., Fairen, A., Yuste, R. & DeFelipe, J. Non-synaptic dendritic spines in neocortex. Neuroscience 145, 464–469. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.12.015 (2007).

Schikorski, T. & Stevens, C. F. Quantitative fine-structural analysis of olfactory cortical synapses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 4107–4112. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.96.7.4107 (1999).

Nusser, Z. et al. Cell type and pathway dependence of synaptic AMPA receptor number and variability in the hippocampus. Neuron 21, 545–559. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80565-6 (1998).

Harris, K. M. & Stevens, J. K. Dendritic spines of CA 1 pyramidal cells in the rat hippocampus: serial electron microscopy with reference to their biophysical characteristics. J. Neurosci. 9, 2982–2997 (1989).

Araya, R., Jiang, J., Eisenthal, K. B. & Yuste, R. The spine neck filters membrane potentials. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 17961–17966. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0608755103 (2006).

Majewska, A., Brown, E., Ross, J. & Yuste, R. Mechanisms of calcium decay kinetics in hippocampal spines: role of spine calcium pumps and calcium diffusion through the spine neck in biochemical compartmentalization. J. Neurosci. 20, 1722–1734 (2000).

Fiala, J. C., Spacek, J. & Harris, K. M. Dendritic spine pathology: cause or consequence of neurological disorders?. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 39, 29–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0165-0173(02)00158-3 (2002).

Spires-Jones, T. & Knafo, S. Spines, plasticity, and cognition in Alzheimer’s model mice. Neural Plast. 2012, 319836. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/319836 (2012).

Merino-Serrais, P. et al. The influence of phospho-tau on dendritic spines of cortical pyramidal neurons in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 136, 1913–1928. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awt088 (2013).

Jimenez-Mateos, E. M. et al. Silencing microRNA-134 produces neuroprotective and prolonged seizure-suppressive effects. Nat. Med. 18, 1087–1094. https://doi.org/10.1038/nm.2834 (2012).

Merino-Serrais, P., Knafo, S., Alonso-Nanclares, L., Fernaud-Espinosa, I. & DeFelipe, J. Layer-specific alterations to CA1 dendritic spines in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Hippocampus 21, 1037–1044. https://doi.org/10.1002/hipo.20861 (2011).

Miwa, H., Fukaya, M., Watabe, A. M., Watanabe, M. & Manabe, T. Functional contributions of synaptically localized NR2B subunits of the NMDA receptor to synaptic transmission and long-term potentiation in the adult mouse CNS. J. Physiol. 586, 2539–2550. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.2007.147652 (2008).

Bashir, Z. I., Alford, S., Davies, S. N., Randall, A. D. & Collingridge, G. L. Long-term potentiation of NMDA receptor-mediated synaptic transmission in the hippocampus. Nature 349, 156–158. https://doi.org/10.1038/349156a0 (1991).

Bosch, C. et al. Reelin regulates the maturation of dendritic spines, synaptogenesis and glial ensheathment of newborn granule cells. Cereb Cortex 26, 4282–4298. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhw216 (2016).

Bosch, C. et al. FIB/SEM technology and high-throughput 3D reconstruction of dendritic spines and synapses in GFP-labeled adult-generated neurons. Front. Neuroanat. 9, 60. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnana.2015.00060 (2015).

Arellano, J. I., Benavides-Piccione, R., Defelipe, J. & Yuste, R. Ultrastructure of dendritic spines: correlation between synaptic and spine morphologies. Front. Neurosci. 1, 131–143. https://doi.org/10.3389/neuro.01.1.1.010.2007 (2007).

Elston, G. N. & DeFelipe, J. Spine distribution in cortical pyramidal cells: a common organizational principle across species. Prog. Brain Res. 136, 109–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0079-6123(02)36012-6 (2002).

Grigoryan, G. & Segal, M. Ryanodine-mediated conversion of STP to LTP is lacking in synaptopodin-deficient mice. Brain Struct. Funct. 221, 2393–2397. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00429-015-1026-7 (2016).

Carlisle, H. J., Fink, A. E., Grant, S. G. & O’Dell, T. J. Opposing effects of PSD-93 and PSD-95 on long-term potentiation and spike timing-dependent plasticity. J. Physiol. 586, 5885–5900. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.2008.163469 (2008).

Schluter, A. et al. Structural plasticity of synaptopodin in the axon initial segment during visual cortex development. Cereb Cortex 27, 4662–4675. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhx208 (2017).

Czarnecki, K., Haas, C. A., Bas Orth, C., Deller, T. & Frotscher, M. Postnatal development of synaptopodin expression in the rodent hippocampus. J. Comp. Neurol. 490, 133–144. https://doi.org/10.1002/cne.20651 (2005).

Steiner, P. et al. Destabilization of the postsynaptic density by PSD-95 serine 73 phosphorylation inhibits spine growth and synaptic plasticity. Neuron 60, 788–802. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.014 (2008).

Migaud, M. et al. Enhanced long-term potentiation and impaired learning in mice with mutant postsynaptic density-95 protein. Nature 396, 433–439. https://doi.org/10.1038/24790 (1998).

Paul, M. H., Choi, M., Schlaudraff, J., Deller, T. & Del Turco, D. Granule cell ensembles in mouse dentate gyrus rapidly upregulate the plasticity-related protein synaptopodin after exploration behavior. Cereb Cortex 30, 2185–2198. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhz231 (2020).

Okubo-Suzuki, R., Okada, D., Sekiguchi, M. & Inokuchi, K. Synaptopodin maintains the neural activity-dependent enlargement of dendritic spines in hippocampal neurons. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 38, 266–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mcn.2008.03.001 (2008).

Deller, T. et al. Synaptopodin-deficient mice lack a spine apparatus and show deficits in synaptic plasticity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 10494–10499. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1832384100 (2003).

Yamazaki, M., Matsuo, R., Fukazawa, Y., Ozawa, F. & Inokuchi, K. Regulated expression of an actin-associated protein, synaptopodin, during long-term potentiation. J. Neurochem. 79, 192–199. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00552.x (2001).

Roth, S. U., Sommer, C., Mundel, P. & Kiessling, M. Expression of synaptopodin, an actin-associated protein, in the rat hippocampus after limbic epilepsy. Brain Pathol. 11, 169–181. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-3639.2001.tb00389.x (2001).

Cohen, J. W. et al. Chronic corticosterone exposure alters postsynaptic protein levels of PSD-95, NR1, and synaptopodin in the mouse brain. Synapse 65, 763–770. https://doi.org/10.1002/syn.20900 (2011).

Davies, C. H., Starkey, S. J., Pozza, M. F. & Collingridge, G. L. GABA autoreceptors regulate the induction of LTP. Nature 349, 609–611. https://doi.org/10.1038/349609a0 (1991).

Deller, T. et al. Lesion-induced axonal sprouting in the central nervous system. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 557, 101–121. https://doi.org/10.1007/0-387-30128-3_6 (2006).

Jedlicka, P. et al. Impairment of in vivo theta-burst long-term potentiation and network excitability in the dentate gyrus of synaptopodin-deficient mice lacking the spine apparatus and the cisternal organelle. Hippocampus 19, 130–140. https://doi.org/10.1002/hipo.20489 (2009).

Vlachos, A., Maggio, N. & Segal, M. Lack of correlation between synaptopodin expression and the ability to induce LTP in the rat dorsal and ventral hippocampus. Hippocampus 18, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1002/hipo.20373 (2008).

Elramah, S. et al. Spinal miRNA-124 regulates synaptopodin and nociception in an animal model of bone cancer pain. Sci. Rep. 7, 10949. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-10224-1 (2017).

Fester, L. et al. Synaptopodin is regulated by aromatase activity. J. Neurochem. 140, 126–139. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnc.13889 (2017).

Fester, L. et al. Estradiol responsiveness of synaptopodin in hippocampal neurons is mediated by estrogen receptor beta. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 138, 455–461. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsbmb.2013.09.004 (2013).

Raza, S. et al. The cholesterol metabolite 27-hydroxycholesterol stimulates cell proliferation via ERbeta in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Cell Int 17, 52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12935-017-0422-x (2017).

Lepagnol-Bestel, A. M. et al. DYRK1A interacts with the REST/NRSF-SWI/SNF chromatin remodelling complex to deregulate gene clusters involved in the neuronal phenotypic traits of Down syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 18, 1405–1414. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddp047 (2009).

Konietzny, A. et al. Myosin V regulates synaptopodin clustering and localization in the dendrites of hippocampal neurons. J. Cell Sci. https://doi.org/10.1242/jcs.230177 (2019).

Harris, K. M. Structural LTP: from synaptogenesis to regulated synapse enlargement and clustering. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 63, 189–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2020.04.009 (2020).

Nakahata, Y. & Yasuda, R. Plasticity of spine structure: local signaling, translation and cytoskeletal reorganization. Front. Synaptic Neurosci. 10, 29. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnsyn.2018.00029 (2018).

Desmond, N. L. & Levy, W. B. Changes in the numerical density of synaptic contacts with long-term potentiation in the hippocampal dentate gyrus. J. Comp. Neurol. 253, 466–475. https://doi.org/10.1002/cne.902530404 (1986).

Fifkova, E. & Van Harreveld, A. Long-lasting morphological changes in dendritic spines of dentate granular cells following stimulation of the entorhinal area. J. Neurocytol. 6, 211–230. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01261506 (1977).

Matsuzaki, M., Honkura, N., Ellis-Davies, G. C. & Kasai, H. Structural basis of long-term potentiation in single dendritic spines. Nature 429, 761–766. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02617 (2004).

Newpher, T. M., Harris, S., Pringle, J., Hamilton, C. & Soderling, S. Regulation of spine structural plasticity by Arc/Arg3.1. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 77, 25–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcdb.2017.09.022 (2018).

Feng, B., Raghavachari, S. & Lisman, J. Quantitative estimates of the cytoplasmic, PSD, and NMDAR-bound pools of CaMKII in dendritic spines. Brain Res. 1419, 46–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2011.08.051 (2011).

Auffret, A. et al. Age-dependent impairment of spine morphology and synaptic plasticity in hippocampal CA1 neurons of a presenilin 1 transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. 29, 10144–10152. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1856-09.2009 (2009).

Roumier, A. et al. Impaired synaptic function in the microglial KARAP/DAP12-deficient mouse. J. Neurosci. 24, 11421–11428. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2251-04.2004 (2004).

Chen, Z. et al. Excitotoxic neurodegeneration induced by intranasal administration of kainic acid in C57BL/6 mice. Brain Res. 931, 135–145. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0006-8993(02)02268-0 (2002).

van Zundert, B. et al. Neonatal neuronal circuitry shows hyperexcitable disturbance in a mouse model of the adult-onset neurodegenerative disease amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J. Neurosci. 28, 10864–10874. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1340-08.2008 (2008).

Mesulam, M., Shaw, P., Mash, D. & Weintraub, S. Cholinergic nucleus basalis tauopathy emerges early in the aging-MCI-AD continuum. Ann. Neurol. 55, 815–828. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.20100 (2004).

Pitt, D., Werner, P. & Raine, C. S. Glutamate excitotoxicity in a model of multiple sclerosis. Nat. Med. 6, 67–70. https://doi.org/10.1038/71555 (2000).

Matthews, C. C., Zielke, H. R., Parks, D. A. & Fishman, P. S. Glutamate-pyruvate transaminase protects against glutamate toxicity in hippocampal slices. Brain Res. 978, 59–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0006-8993(03)02765-3 (2003).

Styr, B. & Slutsky, I. Imbalance between firing homeostasis and synaptic plasticity drives early-phase Alzheimer’s disease. Nat. Neurosci. 21, 463–473. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-018-0080-x (2018).

Franco, R. & Cedazo-Minguez, A. Successful therapies for Alzheimer’s disease: why so many in animal models and none in humans?. Front. Pharmacol. 5, 146. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2014.00146 (2014).

Jolas, T. et al. Long-term potentiation is increased in the CA1 area of the hippocampus of APP(swe/ind) CRND8 mice. Neurobiol. Dis. 11, 394–409. https://doi.org/10.1006/nbdi.2002.0557 (2002).

Ngandu, T. et al. A 2 year multidomain intervention of diet, exercise, cognitive training, and vascular risk monitoring versus control to prevent cognitive decline in at-risk elderly people (FINGER): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 385, 2255–2263. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60461-5 (2015).

Besga, A. et al. Differences in brain cholesterol metabolism and insulin in two subgroups of patients with different CSF biomarkers but similar white matter lesions suggest different pathogenic mechanisms. Neurosci. Lett. 510, 121–126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2012.01.017 (2012).

Schols, L. et al. Hereditary spastic paraplegia type 5: natural history, biomarkers and a randomized controlled trial. Brain 140, 3112–3127. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awx273 (2017).

Bavner, A. et al. On the mechanism of accumulation of cholestanol in the brain of mice with a disruption of sterol 27-hydroxylase. J. Lipid Res. 51, 2722–2730. https://doi.org/10.1194/jlr.M008326 (2010).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the following entities: Margaretha af Ugglas Stiftelse, Gun och Bertil Stohnes Stiftelse, Karolinska Institutet fund for geriatric research, Stiftelsen Gamla Tjänarinnor, Tore Nilsson Stiftelse and Demensfonden to P.M.S. and R.L.V. P.M.S. was the recipient of the EMBO Long-Term Fellowship (ALFT 696-2013), the SSMF postdoctoral Fellowship and Juan de la Cierva (IJCI-2016-27658). R.L.V. and E.V.J. were the recipients of Postdoctoral Fellowships from CONACYT (Mexico, CVU: 209252 and 232099). We also acknowledge grants to R.L.V. from Lindhés Advokatbyra Foundation and the regional agreement on medical training and clinical research (ALF) between Stockholm County Council and Karolinska Institutet. This work was also supported by grants from the following Spanish entities: Centro de Investigación en Red sobre Enfermedades Neurodegenerativas (CIBERNED, CB06/05/0066) and the Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades (grant PGC2018-094307-B-I00).The imaging for this study was performed at the Live Cell Imaging Facility, Karolinska Institutet, Sweden, supported by grants from the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, the Swedish Research Council, the Centre for Innovative Medicine and the Jonasson Center at the Royal Institute of Technology, Sweden. We would like to thank Carmen Álvarez and Lorena Valdés for their helpful assistance, Laura Paternain Markinez for her assistance with the Cyp27Tg colony maintenance and Nick Guthrie for his excellent text editing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RLV and PMS generated the project, performed WB, IHC and morphology experiments. ACM and JF supervised on scientific methodology and approaches, provided the infrastructure, animals and consumables of the project. EV and ML performed LTP experiments. AM generated the IHC data on synaptopodin. GG generated data on synaptic proteins, MGG supervised the project on LTP molecular targets for western blot. All authors made important revisions to the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Loera-Valencia, R., Vazquez-Juarez, E., Muñoz, A. et al. High levels of 27-hydroxycholesterol results in synaptic plasticity alterations in the hippocampus. Sci Rep 11, 3736 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-83008-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-83008-3

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.