Abstract

Behçet disease (BD) is a debilitating multi-systemic vasculitis with a litany of muco-cutaneous manifestations and potentially lethal complications. Meanwhile, psoriasis (PSO) is a cutaneous and systemic inflammatory disorder marked by hyperplastic epidermis and silvery scales, which may be accompanied by a distinct form of arthropathy called psoriatic arthritis (PsA). While the clinical pictures of these two are quite different, they feature some important similarities, most of which may stem from the autoinflammatory components of BD and PSO. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the prospective link between BD and cutaneous and articular manifestations of psoriasis. BD, PSO, and PsA cohorts were extracted using the National Health Insurance Service of Korea database. Using χ2 tests, prevalence of PSO and PsA with respect to BD status was analysed. Relative to non-BD individuals, those with personal history of BD were nearly three times more likely to be diagnosed with PSO. The adjusted odds ratio (aOR) was 2.36 [95% confidence interval (CI), 1.91–2.93, p < 0.001]. Elevated PSO risk was more pronounced in the male BD cohort (aOR = 1.19, 95% CI 1.16–1.23, p < 0.001). In age-group sub-analysis, individuals over 65 years with PSO were one and a half times more likely to be affected with BD, relative to those under 65. The adjusted OR for the older group was 1.51 (95% CI 1.43–1.59, p < 0.001). BD individuals with “healthy” body weight were significantly less likely to be affected by PSO (aOR = 0.59, 95% CI 0.57–0.62, p < 0.001). On the other hand, there was a correlation between BMI and the risk of BD, with the “moderately obese (30–35 kg/m2)” group having an aOR of 1.24 (95% CI 1.12–1.38, p < 0.001). BD patients were also twice more likely to be associated with PsA (aOR = 2.19, 95% CI 1.42–3.38, p < 0.001). However, in contrast to the case of psoriatic disease itself, females were exposed to a greater risk of developing BD compared to the male PsA cohort (aOR = 2.02, 95% CI 1.88–2.16, p < 0.001). As with PSO, older BD patients were exposed to a significantly higher risk of developing PsA (aOR = 3.13, 95% CI 2.90–3.40, p < 0.001). Behçet disease may place an individual at a significantly increased risk of psoriasis, and still greater hazard of being affected with psoriatic arthritis. This added risk was pronounced in the male cohort, and tended to impact senile population, and this phenomenon may be related with the relatively poor prognosis of BD in males and PSO in older patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Behçet disease (BD), a prototype that heads a group of unique inflammatory disorders labelled “variable-vessel systemic vasculitides”, presents a daunting challenge not only in the field of dermatology but across multiple other disciplines in medical science. The earliest written evidence of the illness can be probed back to the time of Hippocrates1. Some two millennia later, Benediktos Adamantiades hinted at the possibility that the ocular, muco-cutaneous, and joint manifestations may all be related to one another2. Then, it was Hulusi Behçet who formally reported the constellation of these perplexing signs as a discrete and syndromic entity in 1937.

The spectrum and severity of disease presentation can be as diversifying as any multi-systemic vascular disorder, from self-limited mucocutaneous findings, to debilitating ophthalmologic manifestations, and invasion into large-sized vessels and the nervous system, some of which cases can be fatal3.

While persons of any race can fall victim to BD, it apparently does not affect all ethnic groups equally. Dubbed “Silk Road Disease” by the locals, the highest incidence of BD has typically been seen in the Eastern Mediterranean Basin and the Middle East, with the figures ranging between 20 and 400 persons per 100,000 population4,5. Within the Western Hemisphere BD remains relatively obscure in terms of awareness among the lay public, presumably due to the relatively low incidence6 (less than 1 case per 100,000). However, in recent years there has been a surge of renewed interests on the enigmatic condition within the academic communities of Europe and the United States. The phenomenon may be attributed to the attraction BD holds as a pan-systemic disease, and the relatively well-founded genetic basis. The latter is perhaps epitomised by the evidence of the strong link to HLA-B51 allele, and the discovery of several other potential genetic loci, which was facilitated by such exhaustive analytic tools as whole genome association study7,8 (WGAS).

BD is an idiopathic disease with many contributory factors, such as infection, genetics, and external stimuli, being implicated as culprits9,10,11. Presently BD is loosely categorized as an autoinflammatory disorder, but autoimmune mechanisms, via various cytokines, also seem to contribute significantly12,13,14. In that regard, many intriguing parallels can be drawn between BD and psoriasis (PSO), which is another chronic, relapsing inflammatory skin disorder often accompanied by involvement of joints (psoriatic arthritis or PsA), along with a litany of systemic manifestations (Table 1).

Although the possibility of certain etiological link between these immune-mediated skin conditions has been entertained for some time now, the question so far has not been adequately addressed, at least on a population level. Taking advantage of the large, population-based cohort data from the National Health Insurance Service of Korea (NHIS) database, the authors decided to delve further into the issue in hope of gaining some valuable insights into the pathogenesis of the two unique entities of dysregulated cutaneous immunity.

Results

Basic demographics

The study cohort was drawn from a pool of 1,113,656 registered subjects on the DB, with nearly equal sex distribution. Geographically, the highest proportion of the cohort was drawn from Seoul and Gyeonggi Province, a metropolitan area surrounding the capital city. Other major cities and their metropolitan provinces of the country were also evenly represented. The cohort was divided into ten income brackets (deciles), and then regrouped as lower (brackets 1 through 4), middle (brackets 5 through 7), or upper (brackets 8 through 10) income tiers. The study cohort was also divided from grade of 0 to 6 according to the extent of their disability, if present (Table 2).

Psoriasis (PSO)

Demographic variables

Table 3 shows the prevalence of PSO according to BD status. In comparison to those with no personal history of psoriatic disease, PSO patients were more than twice likely to be diagnosed with BD (Table 4). The adjusted odds ratio(aOR), accommodating sex, age, BMI (body mass index), and income bracket, was 2.36 (95% CI 1.91–2.93, p < 0.001).

In terms of gender consideration, this pattern of added BD risk was more pronounced in the male PSO cohort compared to the female counterpart. The aOR for females with respect to males was 1.19 (95% CI 1.16–1.23, p < 0.001).

For age group sub-analysis, the study cohort was dichotomized into younger and older groups using 65 years as a cut-off point. The analysis led to the conclusion that older individuals with PSO are one and a half times more likely to be affected with BD, in comparison to the younger (< 65 years) group. The aOR for the former was calculated to be 1.51 (95% CI 1.43–1.59, p < 0.001).

Body mass index (BMI)

To assess the influence of obesity on the PSO-BD relationship, the study cohort was stratified according to BMI value. With respect to the underweight group (BMI < 18.5 kg/m2), BD individuals with “healthy” body weight were significantly less likely to be affected by PSO (aOR = 0.59, 95% CI 0.57–0.62, p < 0.001). On the other hand, there was a correlation between BMI and the risk of BD, with the “moderately obese (30–35 kg/m2)” group having an aOR of 1.24 (95% CI 1.12–1.38, p < 0.001). The result for individuals with even greater degree of obesity was not statistically significant, due to an inadequate sample size.

Socioeconomic status (SES)

We also performed a sub-analysis based on gross income level of the subjects. The effect of PSO on BD was shown to be consistent across the subgroups. With the lower tier (income brackets 0 through 4) taken as a reference, the middle tier showed an OR of 0.98 (95% CI 0.95–1.03, p = 0.032). Meanwhile, the value for the higher tier was 1.05 (95% CI 1.01–1.09, p < 0.001).

Disability

In those without any significant impairment (Grade “0”), the risk of BD was shown to increase by a factor of 2.5 (OR = 2.55, 95% CI 2.33–2.77, p < 0.001). For individuals with mild disability (Grade 1 through 2), the OR was 2.97 (95% CI 2.13–3.82, p = 0.028). However, the association was not statistically significant for the “severe (Grade 3 through 6)” subgroup (OR = 2.66, 95% CI 0.70–4.62, p = 0.322).

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA)

Demographic variables

Table 5 shows the prevalence of PsA according to BD status. Roughly one-fifth of the PSO cohort had PsA concomitantly. Similar to psoriatic skin disease, patients with a personal history of the inflammatory arthritis were roughly twice more likely to be affected by BD (aOR = 2.19, 95% CI 1.42–3.38, p < 0.001, Table 6).

However, in contrast to PSO, PsA females were exposed to a greater risk of developing BD compared to the male PsA cohort (aOR = 2.02, 95% CI 1.88–2.16, p < 0.001). Meanwhile, senility was found to increase the risk of BD more dramatically compared to the case of PSO. The aOR for those aged over 65 years was 3.13 (95% CI 2.90–3.40, p < 0.001).

Body mass index (BMI)

There was a similar relationship between BMI and BD risk in PsA patients. BD patients with optimal body weight were almost three times less likely to develop PSO (aOR = 0.34, 95% CI 0.31–0.39, p < 0.001). The aOR for the “moderately obese” was nearly two (aOR = 1.86, 95% CI 1.56–2.23, p < 0.001). The result for patients with a BMI of over 35 kg/m2 was again inconclusive due to a small sample size.

Discussion

On the surface, BD and PSO render drastically different pictures. The former most often presents with painless oral or genital ulcers accompanied by nonspecific cutaneous lesions, such as those of erythema nodosum15 (EM), while with the latter is accentuated by erythematous and nonpruritic scaly plaques on exposed skin surfaces16,17. Aside from the conspicuous clinical features, however, these two share key common ingredients that play a major role in the immuno-pathophysiology, namely deranged Th1/Th17 regulation18, and the involvement of autoinflammation19,20,21. The word autoinflammation was coined only in recent years, and there are ongoing efforts to cement its conceptual framework. At its inception the term was primarily used to denote a singular group of pyretic conditions of monogenic origin, collectively referred to as periodic fever syndromes. Many of the single-gene abnormalities in these autoinflammation syndromes involve genetic loci that code for vital components in proinflammatory cytokine/chemokine pathways or their associated receptors22,23, perhaps the best-known example being MEFV in Familial Mediterranean Fever24 (FMF). Since then the concept was gradually expanded to encompass a handful of polygenic inflammatory disorders as well, including BD and more recently PSO, entities in which the traditional concept of autoimmunity could not by itself fully account for the pathophysiology.

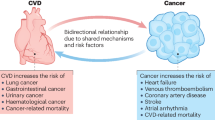

BD and PSO are something of outcasts in the realm of what are commonly understood as “autoimmune disorders”, for they exhibit pathological features pertinent to both autoimmunity and auto-inflammation25,26. In addition, BD and PSO are characterized by similar extracutaneous manifestations (Fig. 1). Clinically, this peculiarity translates into partial or complete absence of several laboratory and histopathological traits that are considered hallmarks of autoimmunity, such as detectable serum auto-antibodies (e.g., anti-DNA or anti-nuclear), female preponderance, and the predominance of lymphocytes as the primary effectors of antigen-independent immune inflammation27,28 (relative to neutrophils and monocytes). On the other hand, the autoinflammatory disorders still reserve a number of key cellular and molecular characteristics that are typically associated with autoimmune tendencies, including dysregulation of both cellular and humoral immunity29, and the strong ties to specific HLA (human leukocyte antigen) alleles30 (Fig. 2). Another distinct attribute that is often used to draw a line between the two is the starring role of innate immunity in the attack directed against host tissues31. Presently, however, whether autoinflammation and autoimmunity are mutually exclusive, or merely divergent points on a spectrum of abnormal conditions in which self-tolerance is disrupted, is a matter of considerable debate.

Features of autoinflammation and autoimmunity. HLA, human leukocyte antigen; Ab, antibody; PSO, psoriasis; PPP, pustulosis palmaris et plantaris; BD, Behçet disease; PAPA, pyogenic arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum and acne syndrome; DIRA, deficiency of the interleukin 1 (IL-1) receptor antagonist; CAPS, cryopyrin-associated autoinflammatory syndromes; FMF, Familial Mediterranean fever; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; DM, diabetes mellitus; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; PM, polymyositis.

Despite these shared features in immune-pathophysiology, how BD and PSO/PsA may interact with each other in terms of disease behaviour is not well understood. Up to this point, the hypothesis has not been tested seriously with large-scale data, although scattered case reports or patient series have consistently pointed out that the former may place the affected individuals at an augmented risk of the latter32, or somehow act as a precipitating factor. Against this backdrop, the present cohort study has estimated that PSO patients are about 2.5 times more likely to be affected with BD. On further analysis, we found that male patients are roughly 20% more vulnerable to the elevation in PSO risk by concomitant BD. This may that the latter exerts an overriding influence on PSO, since it is well established that PSO does not favour either sex in terms of incidence33, and likewise, BD is known to be gender-neutral or even show a modest degree of male predominance34.

Psoriasis is a systemic inflammatory condition, and among the most frequently cited comorbidities are obesity and other “lifestyle” diseases. In the case of BD, the association with metabolic status is less straightforward. A scarce number of reports indicate obesity is not common among BD patients35,36, but simultaneously, there are evidences to suggest that BD does render the patients more vulnerable to other features of metabolic syndrome37,38 (hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia etc.). Harpsøe et al. found that with the exception of celiac disease (CD) and Raynaud’s phenomenon, BMI is associated with several autoimmune diseases39. Our results regarding the BMI covariate was rather interesting, as not only was there a positive correlation between BMI and the risk of PSO in BD patient with BMI over 23, but also a threefold-increase in the risk with sub-optimal BMI (under 18.5 kg/m2).

PsA is a chronic inflammation of both joints and soft connective tissues, that can manifest as either one or any combination of peripheral arthritis, spondylo-arthritis, and enthesitis/dactylitis. It is typically a sero-negative arthritis that begins as an oligo-arthritic disease but it often progresses to involve more joints. It is estimated that up to one third of PSO patients eventually develop PsA as well, and early recognition and prompt intervention is warranted because the inflammation tends to be severe with longer duration of the skin disease. Similarly, the BD-associated arthritis is also a nonerosive, sero-negative oligoarthritic disease which “migrates” to affect many other joints in the body. The prevalence of PsA in our PSO cohort was about 21% (3664 of 17,362), which was in line with published results from other studies. We found that BD individuals were twice more vulnerable to PsA as well, and other subgroup analyses revealed similar patterns that were seen in PSO, with the exception of female dominance.

The present investigation sets itself apart from earlier studies on the potential interrelationship between BD and PSO in several ways. To ensure the validity of the diagnosis, the authors limited data selection to those cases that were diagnosed and treated by certified dermatologists and rheumatologists only. Moreover, this study utilised most exhaustive healthcare database in Korea currently in operation, which contains a comprehensive record pertaining to BD and PSO/PsA during the span of 14 years (from 2002 to 2015). Furthermore, to shield the study results from as many confounding variables as possible, the outcomes values were not only adjusted for sex and age, but by gross income level (brackets) and disability status as well. Indeed, it has been suggested by a multitude of authors that chronic and multisystemic disorders, especially immune-mediated ones, may be influenced by socioeconomic factors and functional impairment40.

This is not to say that our study was completely immune from any shortcomings or limitations. Because the NHIS database was originally intended for insurance-related transactions, retrieval of data pertinent to disease severity or clinical subtypes of BD and PSO was not practical. In addition, the NHIS data, albeit incredibly voluminous, are still hospital-based records, and therefore the study may have been subject to selection bias. Finally, the sample size for the PsA cohort was rather small (n = 21) in comparison to the PsO counterpart. This inherent drawback has a lot to do with our rigorous selection criteria, but it affirms the long-held suspicion that PsA is being underdiagnosed41 (the prevalence is believed to be around 10–30%). The authors believe this to be significant because long-standing PsA can lead to irreversible joint destruction, and therefore early clinical suspicion and recognition is vital, as mentioned previously.

In summing up, the current investigation has backed up the long-held speculation about a potential immunological link between BD and PSO with a solid, population-based evidence. It was revealed that individuals with Behçet disease are twice more likely to develop psoriasis, and also psoriatic arthritis. The risk of psoriasis was correlated with BMI and was significantly higher in sub-optimal BMI. This added risk was pronounced in the male cohort, and tended to impact senile population, and this phenomenon may be related with the relatively poor prognosis of BD in males and PSO in older patients. Further studies are warranted to elucidate the mechanism behind this disease interaction and apply the insight for better-guided clinical practice.

Methods

Database (DB)

This study has been carried out in strict adherence to the Declaration of Helsinki. We used KNHIS-NSC data (NHIS-2016-2-162) provided by National Health Insurance Service (NHIS). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Hallym Medical University Chuncheon Sacred Hospital (IRB No. 2016-05-052). The need for written informed consent was waived by the IRB, because the KNHIS-NSC data set consisted of deidentified secondary data for research purposes.

Regardless of her or his own volition, every South Korean national is covered by the NHIS, a comprehensive, state-enforced healthcare program that has been in effect since 1989. Eligible citizens are covered primarily through community-based plan or alternatively, employee-based plan. The data source for the current investigation was the national health information DB, which is the main body of NHIS-run servers that are considered well-suited for big-data research. The DB is the most comprehensive reservoir that harbours some 1.3 trillion cases of clinical/hospital administration records, including routine medical check-up results, prescription/treatment details, insurance transactions, and nationwide cancer/rare disease registries, from the years 2002–2015.

Cohort definition

We extracted BD and psoriasis cohorts from the research DB using an algorithm suggested by the NHIS. The following two criteria had to be met simultaneously for BD cohort: those who had had at least two consecutive outpatient visits under the KCD7 (Korean Standard Classification of Diseases, 7th revision) Diagnosis Code of M35.2 within the span of at least six months, and 2) those who had undergone pathergy test (prescription code E7113B). On the other hand, the PSO cohort was defined as those who had had at least two consecutive outpatient visits under one of the following KCD Diagnosis codes within the span of at least six months: L40 (Psoriasis), L40.00 (Psoriasis vulgaris), L40.00 (Severe psoriasis vulgaris), L40.08 (Other and unspecified psoriasis vulgaris), L40.8 (Other psoriasis), and L40.9 (Psoriasis, unspecified), and those who have been prescribed (a) topical calcipotriol/betamethasone dipropionate cream (Daivobet®) or gel formulation (Xamiol®), or calcipotriol solution (Daivonex®) for at least three consecutive months, or (b) those who have undergone ultraviolet (UV) phototherapy/photochemotherapy (prescription codes MM331, MM332, MM333, MM334, MM341, MM342, MM343, and MM344) or excimer laser for at least three consecutive months, or 3) those who have been prescribed methotrexate tablets (prescription code A04503121), or cyclosporin capsules (A01206211), or acitretin soft capsules (8806433047801 or 8806433047818) for at least three consecutive months. Similarly, the PsA cohort was obtained with the criteria of (1) those who had had at least two consecutive outpatient visits under one of the following KCD Diagnosis codes, with each visit being at least 6 months apart: M07* (Psoriatic arthropathies), M07.0 (Distal interphalangeal psoriatic arthropathy), M07.2 (Psoriatic spondylitis), and M07.3 (Other psoriatic arthropathies) during at least two outpatient visits, and either (2) evidence of rheumatoid factor (RF) antibody testing or HLA-B27 typing or (3) those who had been prescribed disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs), or biologics/biosimilars approved for psoriatic arthritis, including cyclosporin (L04AD01), hydroxychloroquine (P01BA02), cyclophosphamide (L01AA01), methotrexate (L04AX03), mycophenolate (L04AA06), sulfasalazine (A07EC01), abatacept (L04AA24), rituximab (L01XC02), tocilizumab (L04AC07), adalimumab (L04AB04), certolizumab (L04AB05), etanercept (L04AB01), golimumab (L04AB06), and infliximab (L04AB02).

Statistical analysis

Summary of demographic and baseline characteristics was constructed using descriptive analysis; the mean, maximum, minimum and standard deviation (S.D.) for quantitative variables and the frequency and percentage (%) for qualitative variables. Statistical relationships between BD and PSO/PsA were analysed using χ2 tests and binary logistic regression model. From the cohorts as defined above, odds ratios (OR), 95% confidence intervals (CI), and p values were calculated. The crude OR values were then adjusted by sex, age and gross income level (adjusted OR, or aOR). KSG, a one of the co-authors and an incumbent professor in medical statistics, oversaw the entire procedure of data analytics in the study. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS Enterprise Guide 6.1 M1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, United States) and IBM SPSS software package for Windows (version 19.0, Chicago, IL, United States). All tests were two-sided and p values less than 0.05 were deemed statistically significant.

Data availability

The datasets presented in the current study are freely available from the corresponding.

authors upon request.

References

Verity, D. H., Wallace, G. R., Vaughan, R. W. & Stanford, M. R. Behçet’s disease: from Hippocrates to the third millennium. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 87(9), 1175–1183 (2003).

Sakkas, L. I. & Tronzas, P. The Greek (Hellenic) rheumatology over the years: from ancient to modern times. Rheumatol. Int. 39(6), 947–955 (2019).

Kidd, D. P. Neurological complications of Behçet’s syndrome. J. Neurol. 264(10), 2178–2183 (2017).

Yurdakul, S. & Yazici, H. Behcet’s syndrome. Best Pract. Res. Clin.. Rheumatol. 22(5), 793–809 (2008).

Idil, A. et al. The prevalence of Behcet’s disease above the age of 10 years. The results of a pilot study conducted at the Park Primary Health Care Center in Ankara, Turkey. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 9(5), 325–331 (2002).

Zeidan, M. J., Saadoun, D. & Garrido, M. Behçet’s disease physiopathology: a contemporary review. Auto Immun. Highlights 7(1), 4 (2016).

Yamazoe, K. et al. Comprehensive analysis of the association between UBAC2 polymorphisms and Behçet’s disease in a Japanese population. Sci. Rep. 7(1), 742 (2017).

Kim, S. W. et al. Identification of genetic susceptibility loci for intestinal Behçet’s disease. Sci. Rep. 7, 39850 (2017).

Comarmond, C. & Cacoub, P. Myocarditis in auto-immune or auto-inflammatory diseases. Autoimmun. Rev. 16(8), 811–816 (2017).

Kone-Paut, I. et al. New data in causes of autoinflammatory diseases. Joint Bone Spine 86(5), 554–561 (2019).

Ozguler, Y. et al. Management of major organ involvement of Behçet’s syndrome: a systematic review for update of the EULAR recommendations. Rheumatol. (Oxf.) 57(12), 2200–2212 (2018).

Katsantonis, J. et al. Adamantiades-Behçet’s disease: serum IL-8 is a more reliable marker for disease activity than C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Dermatology 201(1), 37–39 (2000).

Durmazlar, S. P., Ulkar, G. B., Eskioglu, F. & Zouboulis, C. C. Significance of serum interleukin-8 levels in patients with Behçet’s disease: high levels may indicate vascular involvement. Int. J. Dermatol. 48(3), 259–264 (2009).

Polat, M. et al. Classifying patients with Behçet’s disease for disease severity, using a discriminating analysis method. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 34(2), 151–155 (2009).

Emmi, G., Becatti, M., Bettiol, A. & Eksioglu, M. Behçet’s syndrome as a model of thrombo-inflammation: the role of neutrophils. Front Immunol. 10, 1085 (2019).

Vranova, M. et al. Opposing roles of endothelial and leukocyte-expressed IL-7Rα in the regulation of psoriasis-like skin inflammation. Sci. Rep. 9(1), 11714 (2019).

Szél, E. et al. Comprehensive proteomic analysis reveals intermediate stage of non-lesional psoriatic skin and points out the importance of proteins outside this trend. Sci. Rep. 9(1), 11382 (2019).

Diani, M. et al. Increased frequency of activated CD8+ T cell effectors in patients with psoriatic arthritis. Sci. Rep. 9(1), 10870 (2019).

Rivas Bejarano, J. J. & Valdecantos, W. C. Psoriasis as autoinflammatory disease. Dermatol. Clin. 31(3), 445–460 (2013).

Murthy, A. S. & Leslie, K. Autoinflammatory skin disease: a review of concepts and applications to general dermatology. Dermatology 232(5), 534–540 (2016).

Akiyama, M., Takeichi, T. & McGrath, J. A. Autoinflammatory keratinization diseases: an emerging concept encompassing various inflammatory keratinization disorders of the skin. J. Dermatol. Sci. 90(2), 105–111 (2018).

Oike, T. et al. IL-6, IL-17 and Stat3 are required for auto-inflammatory syndrome development in mouse. Sci. Rep. 8(1), 15783 (2018).

Takahashi, T. et al. Cathelicidin promotes inflammation by enabling binding of self-RNA to cell surface scavenger receptors. Sci. Rep. 8(1), 4032 (2018).

Burillo-Sanz, S. et al. Behçet’s disease and genetic interactions between HLA-B*51 and variants in genes of autoinflammatory syndromes. Sci. Rep. 9(1), 2777 (2019).

Direskeneli, H. Autoimmunity versus autoinflammation in Behcet’s disease: do we oversimplify a complex disorder?. Rheumatol. (Oxf.) 45(12), 1461–1465 (2006).

Liang, Y., Sarkar, M. K., Tsoi, L. C. & Gudjonsson, J. E. Psoriasis: a mixed autoimmune and autoinflammatory disease. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 49, 1–8 (2017).

Yazıcı, H. The place of Behcet’s Syndrome among the autoimmune diseases. Intern. Rev. Immunol. 14, 1–10 (1997).

Gül, A. Pathogenesis of Behçet’s disease: autoinflammatory features and beyond. Semin. Immunopathol. 37(4), 413–418 (2015).

de Pineton Chambrun, M., Wechsler, B., Geri, G., Cacoub, P. & Saadoun, D. New insights into the pathogenesis of Behçet’s disease. Autoimmun. Rev. 11(10), 687–698 (2012).

Mahmoudi, M. et al. Epistatic interaction of ERAP1 and HLA-B*51 in Iranian patients with Behçet’s disease. Sci. Rep. 8(1), 17612 (2019).

Thieblemont, N., Wright, H. L., Edwards, S. W. & Witko-Sarsat, V. Human neutrophils in auto-immunity. Semin. Immunol. 28(2), 159–173 (2016).

Cho, S., Cho, S. B., Choi, M. J., Zheng, Z. & Bang, D. Behçet’s disease in concurrence with psoriasis. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 27(1), e113–e118 (2013).

Griffiths, C. E. & Barker, J. N. Pathogenesis and clinical features of psoriasis. Lancet 370(9583), 263–271 (2007).

Maldini, C., Druce, K., Basu, N., LaValley, M. P. & Mahr, A. Exploring the variability in Behçet’s disease prevalence: a meta-analytical approach. Rheumatol. (Oxf.) 57(1), 185–195 (2018).

Koca, S. S. et al. Low prevalence of obesity in Behçet’s disease is associated with high obestatin level. Eur. J. Rheumatol. 4(2), 113–117 (2017).

Bray, G. A. & Bellanger, T. Epidemiology, trends, and morbidities of obesity and the metabolic syndrome. Endocrine 29, 109–117 (2006).

Oguz, A., Dogan, E. G., Uzunlulu, M. & Oguz, F. M. Insulin resistance and adiponectin levels in Behçet’s syndrome. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 25(4), S118–S119 (2007).

Yalçın, B., Gür, G., Artüz, F. & Alli, N. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome in Behçet disease: a case-control study in Turkey. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 14(5), 421–425 (2013).

Harpsøe, M. C. et al. Body mass index and risk of autoimmune diseases: a study within the Danish National Birth Cohort. Int. J. Epidemiol. 43(3), 843–855 (2014).

Hahn, H. J., Kwak, S. G., Kim, D. K. & Kim, J. Y. A nationwide, population-based cohort study on potential autoimmune Association of Ménière Disease to Atopy and Vitiligo. Sci. Rep. 9(1), 4406 (2019).

Burden, A. D. et al. Diagnosis and management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in adults: summary of SIGN guidance. BMJ 341, c5623 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (Grant Number: HI17C2412) and by the Bio and Medical Technology Development Program of the National Research Foundation (NRF), funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (NRF-2017M3A9E8033231 to Dong-Kyu Kim).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.K., D.K., and H.H. designed and conducted the study. H.H. produced the manuscript. S.K. and J.K. carried out calculations and statistics. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. H.H. and S.K. are co-first authors, and contributed equally. D.K. and J.K. are co-corresponding authors, and contributed equally.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hahn, H.J., Kwak, S.G., Kim, DK. et al. Association of Behçet disease with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Sci Rep 11, 2531 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-81972-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-81972-4

This article is cited by

-

Autophagy-related genes in Egyptian patients with Behçet's disease

Egyptian Journal of Medical Human Genetics (2022)

-

Using hierarchical similarity to examine the genetics of Behçet’s disease

BMC Research Notes (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.