Abstract

Complete removal of cancerous tissue and preservation of breast cosmesis with a single breast conserving surgery (BCS) is essential for surgeons. New and better options would allow them to more consistently achieve this goal and expand the number of women that receive this preferred therapy, while minimizing the need for re-excision and revision procedures or more aggressive surgical approaches (i.e., mastectomy). We have developed and evaluated a regenerative tissue filler that is applied as a liquid to defects during BCS prior to transitioning to a fibrillar collagen scaffold with soft tissue consistency. Using a porcine simulated BCS model, the collagen filler was shown to induce a regenerative healing response, characterized by rapid cellularization, vascularization, and progressive breast tissue neogenesis, including adipose tissue and mammary glands and ducts. Unlike conventional biomaterials, no foreign body response or inflammatory-mediated “active” biodegradation was observed. The collagen filler also did not compromise simulated surgical re-excision, radiography, or ultrasonography procedures, features that are important for clinical translation. When post-BCS radiation was applied, the collagen filler and its associated tissue response were largely similar to non-irradiated conditions; however, as expected, healing was modestly slower. This in situ scaffold-forming collagen is easy to apply, conforms to patient-specific defects, and regenerates complex soft tissues in the absence of inflammation. It has significant translational potential as the first regenerative tissue filler for BCS as well as other soft tissue restoration and reconstruction needs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in women, with over 2 million new cases every year world-wide and approximately 330,000 per year in the United States alone1,2. It is estimated that 60–70% of cases per year (~ 1.3 million globally) are treated with breast conserving surgery (BCS; otherwise known as lumpectomy). BCS involves removal of the tumor along with a cancer-free margin of healthy tissue (negative margins), preferably through a small, cosmetically placed incision. BCS with adjunct radiation is preferred over mastectomy (i.e., removal of the whole breast) for eligible patients, because it yields equivalent survival while preserving patients’ breasts and reducing surgery time, recovery time, and complications3,4,5. Since 5- and 10-year survival rates for women with breast cancer are relatively high, greater than 90%2, long-term outcomes and survivorship are especially important when treating this disease. Specifically, for BCS, complete removal of cancerous tissue and preservation of breast shape, appearance, and consistency (i.e., pleasing breast cosmesis) in a single surgery are paramount to achieving satisfactory outcomes and patient quality of life.

According to the American Society of Breast Surgeons, standard guidelines for BCS involve “closing the surgical defect in layers as cosmetically as possible” following resection of the tumor6. Healing of the complex surgical wound follows, initially with a seroma or hematoma forming in the defect, followed by scar formation and contraction. For surgeons, it is extremely challenging, if not impossible, to predict the cosmetic outcome of BCS, especially given significant patient variation in breast tumor size, shape, and location, and the unpredictable nature of the tissue repair process, which is compounded by the effects of adjunct radiation therapy. Because of this, there remains a relatively high level of BCS-related breast deformities, with approximately one-third of women developing dents, distortions, and asymmetry between breasts7,8. Such outcomes are known to negatively impact the self-esteem, body image, and intimacy of breast cancer survivors, contributing to overall feelings of insecurity, anxiety, and depression9,10. Furthermore, the need for secondary surgical procedures, which increases healthcare costs, remains high for BCS, with estimates ranging from 20 to 40%11,12. This includes re-excisions due to positive margins as well as revision and reconstruction procedures to repair breast deformities. Due to these concerns, BCS may not be an ideal option for all women, especially those with tumors that are large in comparison to breast size (> 5 cm in diameter; tumor:breast volume percent greater than 1.5%) or positioned within the lower quadrants of the breast13,14,15. Therefore, breast surgeons are in need of new options to further optimize oncologic and cosmetic outcomes of BCS, enabling them to confidently offer this conservative therapy to more patients with satisfying outcomes.

At present, there are no commercial products that allow surgeons to predictably restore, reconstruct, or regenerate soft tissues, such as the breast. Furthermore, it is apparent that breast surgeons are actively looking for solutions to this problem. For example, BioZorb represents a relatively new, three-dimensional, spiral-shaped tumor bed marker intended to mark the surgical cavity for targeted post-operative radiation. However, breast surgeons have used this bioresorbable device with hopes that it would also assist in filling the tissue void and improving cosmetic results. Published clinical studies indicate that both surgeons and patients have been uniformly dissatisfied with BioZorb since this implant is relatively expensive, does not significantly improve outcomes, and gives rise to a hard, palpable lump that lasts for up to 2.8 years and causes patient discomfort16,17.

On the other hand, there are two surgical reconstruction options which aim to improve BCS cosmetic outcomes, namely autologous fat grafting (also known as lipofilling or fat transfer) and oncoplastic surgery18,19. Fat grafting involves harvesting fat (adipose tissue) via liposuction from one area of the patient’s body and re-injecting minimally processed fat cells into another region. Originally fat grafting was used for delayed breast reconstruction procedures, but more recently it has been investigated for use immediately following BCS. While this approach has seen some success, persistent challenges remain, including rapid reabsorption leading to significant volume loss (ranging from 25 to 80%), fat necrosis, oil cyst formation, micro-calcifications, and questions around oncologic safety (i.e., cancer recurrence)20,21,22,23. As an alternative approach, oncoplastic surgery combines the skills of surgical oncology with the techniques of plastic surgery to reconstruct one or both breasts at the time of lumpectomy. Oncoplastic procedures include both volume displacement (rearrangement of remaining healthy breast tissue) and volume replacement (reconstruction with various autologous tissue flaps) techniques. While oncoplastic surgery offers the advantage of using the patient’s own tissue, this approach is limited by need for specialized training, involvement of multiple surgeons, longer surgical procedures, and increased cost18,24.

In the present study, we aimed to develop and evaluate a soft tissue filler that would (1) predictably restore and regenerate damaged tissue and tissue voids, (2) be easily applied, (3) conform to patient-specific defects varying broadly in size and geometry, and (4) not interfere or compromise routine clinical processes and procedures. In particular, type I oligomeric collagen (oligomer), a highly-purified molecular form of collagen that is readily soluble in dilute acid25,26, represents a tunable, in situ forming biomaterial with potential to address many of these design considerations. Unlike conventional monomeric collagen preparations, namely telocollagen and atelocollagen, oligomer represents small aggregates of full-length triple-helical collagen molecules (i.e., tropocollagen) with carboxy- and amino-terminal telopeptide intact, held together by a naturally-occurring intermolecular crosslink. The preservation of these key molecular features provides this natural polymer with desirable but uncommon properties. More specifically, oligomer retains its fibril-forming (self-assembly) capacity, which is inherent to fibrillar collagen proteins and yields scaffolds which recreate the structural and biological signaling features of collagen scaffolds found in the extracellular matrix (ECM) component of tissues25,26. Further, upon neutralization to physiologic conditions (e.g., pH and ionic strength), oligomer solutions can be readily applied to fill complex contours and geometries, where the liquid rapidly transitions to a fibrillar collagen scaffold27,28,29. Upon in vivo implantation, these scaffolds persist, showing slow metabolic turnover and remodeling, resistance to proteolytic degradation, and no active biodegradation or foreign body response27,28,29,30,31,32,33. Finally, oligomer supports creation of materials with broadly tunable physical properties, including geometry, architecture (random or aligned fibrils, continuous fibril density gradients), and mechanical integrity30,31,33,34,35,36,37, making it an enabling platform for personalized regenerative medicine.

Here, we evaluated prototype oligomer formulations specifically designed to serve as a regenerative filler for damaged or defective soft tissues, such as the tissue void created by BCS. First, prototype in situ forming collagen scaffolds were characterized based on molecular purity, polymerization (self-assembly) time, and viscoelastic properties. To evaluate biocompatibility and effectiveness of these scaffolds, simulated lumpectomy procedures were performed on the breasts (mammary glands) of pigs. Prototype formulations were used to fill a subset of lumpectomy voids, and surgical outcomes were compared to untreated defects (no fill; negative control) and normal breasts on which no surgery was performed (positive controls). To define the tissue response timeline and gain insight into oligomer mechanism of action, a 16-week longitudinal study was performed. Additionally, a second study was conducted to assess how the collagen scaffold and its associated tissue response was affected by post-operative irradiation. Outcome measures included semi-quantitative visual and palpation-based examination, ultrasonography, radiography, and gross and histological analyses. Combined, these data provide preclinical support for the use of this regenerative tissue filler during breast conserving surgery.

Results

Liquid collagen conforms to geometry and transitions to stable, fibrillar scaffold with properties similar to soft tissues

Prototype scaffold-forming collagen formulations were obtained as kits from GeniPhys (Zionsville, Indiana). As shown in Fig. 1a, the kit consisted of a syringe containing sterile type I oligomeric collagen in dilute acid (0.01 N hydrochloric acid), a syringe containing a sterile proprietary neutralization solution, a sterile luer-lock adapter, and a sterile applicator tip. Immediately prior to use, the two syringes were joined with the luer-lock adapter (Fig. 1b) and the collagen and neutralization reagent mixed at a ratio of 9 to 1, bringing the collagen solution to physiologic pH and ionic strength. After mixing, the viscous liquid could be injected into various geometries, where it conformed to the shape prior to transitioning into a physically-stable, fibrillar collagen scaffold (Fig. 1b, Supplementary Video S1). To demonstrate collagen purity, sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) was performed using 4–20% and 6% gels. Gels revealed a banding pattern characteristic of oligomeric collagen25 with no detectable contaminating non-collagenous proteins or other types of collagens (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Fig. S1). Other functional performance parameters, including polymerization time and viscoelastic properties of formed collagen scaffolds, were measured, with a summary provided in Fig. 1d. Specifically, the concentration of oligomer prior to neutralization was roughly 7.7 mg/mL. Upon neutralization, the scaffold-forming reaction took, on average, just under 1 min, as measured rheometrically at 37 °C. When analyzed in oscillatory shear and unconfined compression, the formed scaffold exhibited solid-like behavior with shear storage (G′) and loss (G″) moduli of 3.16 ± 0.16 kPa and 0.40 ± 0.02 kPa, respectively, and a compressive modulus of 7.67 ± 0.42 kPa. Although scaffold properties are tunable across a broad range of elastic modulus and strength values, the formulations tested here were designed to exhibit viscoelastic properties similar to soft tissues.

Purified liquid collagen forms viscoelastic fibrillar scaffold with soft tissue-like properties. (a) Kit consisting of syringe containing sterile type I oligomeric collagen solution, a syringe of propriety neutralization (self-assembly) buffer, a luer-lock adapter, and applicator tip. (b) Images showing mixing of two reagents followed by injection into a plastic mold maintained at body temperature (37 °C), where the liquid transitions into a stable, shape-retaining fibrillar collagen scaffold. (c) SDS–PAGE (4–20% and 6% gels) documenting purity and characteristic banding pattern of type I oligomeric collagen. Images represent full length gels and show all relevant lanes. Lane 1: molecular weight standard. Lane 2: type I oligomeric collagen. Uncropped images of the full gel length are shown in Supplementary Figure S1. (d) Table summarizing collagen polymerization kinetics and performance specifications (mean ± SD; N = 4, n = 6–8) of prototype collagen scaffold.

Collagen scaffold maintains volume; induces vascularization and breast tissue regeneration with no inflammation

To evaluate the effectiveness of the scaffold-forming collagen as a regenerative filler for soft tissue defects, a longitudinal study was performed involving simulated lumpectomy procedures on breasts of normal, healthy Yucatan mini-pigs (Fig. 2). Female mini-pigs represent the preferred large animal model for such translational studies based on their size and anatomical and physiological similarities to humans38. Additionally, pigs generally have twelve mammary glands (breasts), which reduced the total number of animals required for the studies since each breast could serve as an experimental or control group. Roughly one quarter of breast tissue volume was excised (Fig. 2e), which ranged from 2 to 5.5 mL of tissue (average ~ 3 mL) depending upon individual breast size (Fig. 2a). For collagen-treated breasts, the liquid collagen was mixed and immediately injected into the tissue void, where it conformed to the complex geometry prior to transitioning to a fibrillar collagen scaffold in less than 5 min under these circumstances (Fig. 2b–d). The breast surgeon used her discretion when filling each defect, with applied collagen volumes varying with defect size and geometry. Surgical voids were filled with at least the same volume of collagen as tissue removed, with the majority receiving 1–2 mL more collagen volume. Negative control sites were left untreated (no fill), which is consistent with standard-of-care BCS procedures. All incisions were closed using resorbable sutures and bandaged (Fig. 2f). All animals maintained weight (± 5 kg), surgical sites remained closed, and no procedural complications occurred throughout the duration of the study (Fig. 2g).

Overview of simulated lumpectomy procedure. (a) Table summarizing surgically excised mammary tissue volume, which represented roughly one-fourth total breast tissue volume. Data (mean ± SD) compiled from both longitudinal and radiation studies (1 week: collagen filler: n = 12, no fill = 6; 4 weeks: collagen filler: n = 18, no fill: n = 9; 16 weeks: collagen filler: n = 18, no fill: n = 9). Surgical void (b) before and (c) after filling with collagen. (d) Application of scaffold-forming collagen. (e) Excised mammary tissue. Surgical sites (f) immediately following surgery showing bandaging and (g) 16 weeks following simulated lumpectomy with irradiation.

Consistent with what is observed amongst women and men, pig breasts were found to vary in volume, consistency, and composition both within and between individual animals. At the microscopic level (Supplementary Fig. S2), mammary glands consisted of multiple lobes, composed of smaller secretory lobules organized as clusters and a system of ducts (channels) that eventually exited the skin via the nipple. The lobules and ducts were supported by an intralobular stroma, composed predominantly of fibrous type I collagen. Additionally, collagenous connective tissue was found between lobes (interlobular stroma), providing support to the breast and determining its shape. Adipose tissue, which primarily determines breast size, filled the space between the glandular and fibrous connective tissue. When evaluated in unconfined compression, breasts located cranially (toward the head) were relatively stiff, with an average compression modulus of 19.0 ± 12.9 kPa. Progressing caudally (toward the tail), breasts increased in fat composition and were softer, with an average compression modulus of 6.56 ± 2.51 kPa for the most caudal breasts.

To assess biocompatibility and tissue response of the collagen filler, animals were anesthetized at designated time points of 1, 4, and 16 weeks. All breasts were examined visually, palpated, and semi-quantitatively scored in a blinded fashion according to criteria in Supplementary Fig. S3. Collagen-treated and no fill control breasts showed no evidence of erythema (redness) or eschar (sloughing, dead tissue) at any time point. Mild edema was evident at 1 week in breasts on which surgery was performed; however, the extent of swelling was similar for both collagen and no fill groups and subsided shortly thereafter. Uniformity/consistency scores for collagen-treated breasts were similar to no fill controls at all three time points, decreasing from roughly 1.2 at 1 week to 0.25 by 16 weeks (Fig. 3a). Such findings are important because they indicate that the collagen filler does not create breast inconsistencies that could be interpreted clinically as residual disease or a source of patient discomfort. All normal breasts received a score of zero. Additionally, when the breast surgeon performed simulated surgical re-excision on collagen-treated breasts, the fill material did not compromise or interfere with the procedure.

Collagen filler persists and induces site-appropriate tissue regeneration. (a) Graph showing breast uniformity/consistency scores (mean ± SD; collagen: n = 12; no fill: n = 6) assigned by breast surgeon for collagen and no fill (negative control) treated voids at various time points following simulated lumpectomy. All no surgery breasts scored 0. (b) Cross-sections of surgical voids following treatment with collagen or no fill compared to normal breast tissue. Arrows represent surgical clips placed to mark boundaries of surgical void.

Biocompatibility and tissue response of the collagen filler were further defined based on gross and histological examination of transverse sections of breast explants, with comparisons to no fill and normal breast controls. From these analyses, it was apparent that the collagen filler maintained its volume (minimized defect contraction), was highly biocompatible, and exhibited a regenerative tissue response in absence of an inflammatory reaction or foreign body response. As cells infiltrated the scaffold and new breast tissue was generated, it took on a tissue-like appearance that was difficult to discern grossly from surrounding normal tissue (Fig. 3b). In this case, the surgical clips were useful as markers of the original defect margins (Figs. 3b, 4). Upon histological analysis at 1 week, the collagen filler was evident within the tissue void, where it appeared as a homogenous, light pink (eosinophilic) staining material (Fig. 4a). Often surrounding the filler was a band of hemorrhage, fibrin, and a few leukocytes, which was attributable to the surgical manipulation of the tissue (Fig. 4a). At the filler-host tissue interface, there were focally extensive areas of proliferating fibroblasts (mesenchymal cells) with few small-caliber vessels infiltrating the scaffold edges. The surrounding breast tissue appeared largely normal, with remodeling areas adjacent to the surgical site. These regions contained aggregates of remodeling epithelial cells, some of which appeared to be ductules while others were more irregularly shaped, suggestive of rudimentary lobules (Fig. 4a). It is noteworthy that there was no evidence of an inflammatory-mediated foreign body reaction or active biodegradation that is characteristic of conventional implantable materials39. At the 4-week time point, fibroblasts, along with newly formed vasculature, extended into deeper portions of the collagen filler, with infiltrating cells most abundant at the periphery and dwindling further into the center (Fig. 4a). Multifocal aggregates of epithelial cells were observed, which were again consistent with precursors of glandular structures (Fig. 4a). By 16 weeks, the scaffold was completely cellularized, appearing as mature, remodeled collagen fibers and bundles, with some sites displaying small discernible regions of acellular eosinophilic filler material. Small caliber vessels were present diffusely and evenly distributed throughout the scaffold (Fig. 4a). Within the vascularized collagen scaffold, adipose tissue and cytokeratin-positive lobules and ducts were present, especially at the periphery (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Fig. S4). The glandular morphology was well developed and mature with no remarkable pathology.

Collagen filler supports breast tissue neogenesis without evoking an inflammatory response. (a) Cross-sections (H&E) of collagen filled voids at 1 week, 4 weeks, and 16 weeks following simulated lumpectomy. Low magnification images show treated voids and their interface with the surrounding host tissue (large arrows indicate surgical clip sites). High magnification images feature the central region of the collagen filler and the filler/host tissue interface. Cellular infiltration, vascularization, and site-appropriate tissue generation of the scaffold occur over time. By 16 weeks, the collagen is completely cellularized and vascularized (small arrows indicated blood vessels) with evidence of regenerated mammary gland (RG) and adipose tissue (RF). Onc: oligomer scaffold with no cell infiltration, Oc: oligomer scaffold with cellular infiltrate. (b) Cross-sections (H&E) of untreated (no fill) surgical voids at 1 week, 4 weeks, and 16 weeks following simulated lumpectomy. Low magnification images show voids and the surrounding host tissue. High magnification images feature the central region of the voids and the void/host tissue interface. Hematomas (H) were commonplace at 1 week, followed by progressive defect contraction and scar tissue formation (S).

By contrast, at 1 week, hematoma formation was evident upon both gross and histological evaluation of no fill breast explants (Figs. 3b, 4b). Hemorrhage, fibrin clot, and leukocytes were evident within the lumpectomy site. Intermixed within areas of hemorrhage were proliferating fibroblasts with few small caliber vessels, consistent with fibrovascular tissue associated with reparative wound healing. Scattered necrotic regions with active inflammation were also apparent surrounding the defect area. By 4 weeks, these tissue defects contracted as evidenced by significant clip displacement grossly and a star-like, constricted appearance histologically (Fig. 4b). Fibrovascular scar tissue was prominent within the defect area, with multiple, small regions of necrosis and inflammation noted throughout and near the defect border (Fig. 4b). Active remodeling of glandular and adipose tissue was observed in tissue regions surrounding the defect (Fig. 4b). By 16 weeks, the fibrous scar tissue increased in density, appearing as differentially oriented swirls of parallel-aligned fibrous tissue densely populated by myofibroblasts. While lobules, ducts, and adipose tissue were identified surrounding the defect, multiple glands with poorly developed morphological features were found within the scar tissue periphery, as evidenced by the presence of inflammatory cells and low-level, diffuse cytokeratin staining. (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Fig. S4).

Collagen scaffold does not compromise interpretation of sonograms and radiographs

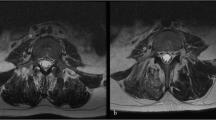

Mammography and ultrasonography are routinely used as follow-up diagnostic procedures to BCS to monitor for cancer recurrence. To ensure that the collagen filler did not compromise or interfere with image interpretation, ultrasound was performed on all pig breasts prior to euthanasia and radiographs were taken of each individual whole breast following mastectomy. Sonograms obtained over the 16-week study showed that the collagen scaffold did not obscure or prevent interrogation of breast tissue and did not produce any regions of unexpected echogenicity (Fig. 5a). At 1 week, a large, irregularly-shaped hypoechoic region was observed within collagen-treated breasts containing varying degrees of heterogeneous echoes (Fig. 5a). Such signals were not surprising given that the filler microstructure represents a randomly-oriented meshwork of collagen fibrils measuring roughly 400 μm in diameter25. While these regions appeared to maintain their volume over time, they gradually took on the appearance of normal tissue, which corroborated the cellularization and vascularization observed within gross explants and histologically (Fig. 5a). No fill treated voids also showed an irregular-shaped hypoechoic region consistent with seroma and hemorrhage at 1 week (Fig. 5a). By 4- and 16-week time points, these regions diminished in size, producing a heterogeneous signal consistent with contraction and scar formation (Fig. 5a).

Collagen filler does not interfere with radiography or ultrasonography. Representative (a) ultrasound images and (b) radiographs of surgical voids treated with collagen or no fill compared to normal breast tissue at 1-week, 4-week, and 16-week time points. Radiopaque marker clips evident within radiographs indicate boundaries of surgical void and show evidence of contraction for no fill voids.

The collagen scaffold also did not interfere with radiograph interpretation, but rather displayed an opacity consistent with normal tissue throughout the duration of the study (Fig. 5b). Additionally, radiographs provided further evidence that the collagen scaffold maintained the void volume with limited clip displacement over time (Fig. 5b). The majority of untreated (no fill) surgical voids also produced radiographs that appeared consistent with normal tissue at 1 week, with a small number of sites displaying obvious darkened regions consistent with an air pocket, seroma, or hematoma (Fig. 5b). The progressive displacement of surgical clips observed at 4- and 16-week time points provided further evidence of defect contraction and scarring over time (Fig. 5b).

Irradiation does not adversely affect collagen filler or regenerative response

To determine if the collagen filler was compatible with radiation therapy, a cohort of animals was subjected to ventral irradiation two weeks following the simulated lumpectomy procedure, with each animal receiving a total dose of 20 Gy over 5 consecutive days. Irradiated animals displayed an increase in skin pigmentation over time as evidenced by a darkening of skin color (Fig. 2g), which would be expected in humans undergoing therapeutic irradiation as well. At the microscopic level, moderate hyperplasia or thickening of the epidermis was evident with increased melanin deposition especially within the basal epidermis (Supplementary Fig. S2). At 16 weeks, breast tissue was noticeably stiffer, again a common change observed with radiation therapy40. Additionally, signs of fat necrosis and atypical hyperplasia of ducts and glands were evident (Supplementary Fig. S2)41.

With the exception of differences in skin pigmentation, all breasts and surgical sites healed well, appearing similar to those of non-irradiated animals. Average breast uniformity/consistency scores for collagen-treated and no fill groups were somewhat higher in irradiated versus non-irradiated animals at the respective time points, with the only exception being the 16-week collagen-treated group, where scores were similar (Figs. 6a, 3a). Examination of gross explants and histological cross-sections revealed no obvious adverse effect of irradiation on the collagen scaffold or its associated tissue response; however, subjectively, the overall healing timeline of irradiated sites appeared modestly delayed (Fig. 6b,c). Over the 16-week study period, the collagen filler persisted within the surgical site, inducing progressive cellularization, vascularization, and breast tissue regeneration, which proceeded inward from the filler-host tissue interface. As expected, the no fill group showed contraction and the development of fibrous scar tissue (Fig. 6b,d). Sonograms (Fig. 7a) and radiographs (Fig. 7b) were largely similar for irradiated and non-irradiated animals, again confirming that the collagen filler was not negatively affected by irradiation and did not produce any suspicious imaging anomalies.

Radiation has little to no effect on collagen filler and associated tissue response. (a) Graph showing breast uniformity/consistency scores (mean ± SD; collagen: n = 6; no fill: n = 3) assigned by breast surgeon for collagen treated and no fill (negative control) voids at various time points following simulated lumpectomy and radiation. All no surgery breasts scored 0. (b) Cross-sections of surgical voids following treatment with collagen or no fill and radiation compared to no surgery normal breast tissue. Arrows represent surgical clips placed to mark boundaries of surgical void. (c) Cross-sections (H&E) of collagen filled voids at 4 weeks and 16 weeks following simulated lumpectomy with irradiation. Low magnification images show treated voids and their interface with the surrounding host tissue. High magnification images feature the central region of the collagen filler and the filler/host tissue interface. Cellular infiltration, vascularization, and site-appropriate tissue generation of the collagen implant occur over time, albeit at a slower rate than sites from non-irradiated animals. By 16 weeks, the collagen is completely cellularized and vascularized (small arrows indicated blood vessels) with evidence of regenerated adipose tissue (RF). Onc: oligomer scaffold with no cell infiltration, Oc: oligomer scaffold with cellular infiltrate. (d) Cross-sections (H&E) of untreated (no fill) surgical voids at 4 weeks and 16 weeks following simulated lumpectomy with radiation. Low magnification images show voids and the surrounding host tissue, with scar tissue (S) and a suture-related granuloma (G) evident at 4 weeks (large arrow indicates surgical clip site). High magnification images feature the central region of the scar tissue and the scar/host tissue interface.

Collagen filler does not compromise interpretation of diagnostic images of breast tissue even after irradiation. Representative (a) ultrasound images and (b) radiographs of surgical voids treated with collagen or no fill and irradiation compared to normal breasts at 4-week and 16-week time points. Radiopaque marker clips evident within radiographs indicate boundaries of surgical void and show evidence of contraction for no fill voids.

Discussion

Identifying a therapeutic approach that more predictably and consistently preserves breast shape and appearance following BCS would bring more confidence to both surgeons and patients when selecting conservative therapy such as BCS. Additionally, it would assist in maintaining the quality of life and emotional well-being of millions of breast cancer survivors each year worldwide. Such an approach would also benefit other patient populations in need of soft tissue restoration or reconstruction, including children with congenital defects, individuals suffering from traumatic injuries, and cancer patients requiring resection of tumors within tissues other than breast (e.g., skin, muscle). The mammary glands of miniature swine have been routinely used to evaluate innovative strategies to improve outcomes of breast surgical procedures42,43. Here, by performing simulated lumpectomy procedures on female mini-pigs, we show that an in situ forming scaffold formulated from type I oligomeric collagen addresses a number of surgeon and patient needs, with the potential to translate as the first regenerative soft tissue filler. More specifically, our findings show that this specially formulated collagen is easy to use and can be readily applied as part of a surgical procedure (e.g., tumor excision) without disrupting normal workflow. Its liquid format readily fills and conforms to patient-specific defect geometries and contours and is amenable to minimally invasive procedures27,28,29. Once injected into the site, oligomer rapidly transitions to a physically-stable fibrillar collagen scaffold that persists and maintains its volume. As a natural and unmodified fibrillar collagen scaffold, it restores critical biochemical and biomechanical signaling to cells, inducing site-appropriate regeneration of complex tissue compositions, including those found in the breast, in absence of an inflammatory reaction or foreign body response. Finally, we show that the material is compatible with a number of standard clinical procedures, including irradiation, radiography, ultrasonography, and surgical re-excision.

The collagen filler described here is fundamentally different from conventional flowable and injectable collagen products that are or have previously been used for soft tissue augmentation (e.g., cosmetic procedures), management of skin wounds (e.g., ulcers), and tissue bulking (e.g., urinary incontinence). Such products, which include Zyderm, Zyplast, Integra Flowable, and Contigen, are fashioned from reconstituted, enzymatically-treated collagen (atelocollagen) or granulated tissue particulate derived from bovine, porcine, or human tissue sources. To make these materials injectable, the insoluble fibrous collagen or tissue particulate is suspended in physiologic saline solutions to create dispersions or suspensions. All of these implantable collagens are temporary and exhibit rapid biodegradation (reabsorption; 1–6 months), where they are actively degraded via inflammatory-mediated processes, including phagocytosis by macrophages/giant cells and proteolytic degradation by secreted matrix metalloproteinases44. To slow degradation and improve persistence, many of these products are treated with glutaraldehyde or other exogenous crosslinking processes45.

By contrast, oligomer represents a molecular subdomain found within natural tissue collagen fibers (e.g., porcine dermis), which can be extracted and purified so that it is free from cellular and other immunogenic tissue components. The type I collagen protein and crosslink chemistry comprising this subdomain are highly conserved across species46, documenting the significance of this major structural element within the body. Physiologic conditions induce fibril formation, where oligomer molecules assemble into staggered arrays, giving rise to interconnected networks or scaffolds of fibrils25,26,36. Published studies show that formed scaffolds are largely similar to those found naturally within the extracellular matrix, comprising fibrils with regular D-banding patterns that readily engage in biosignaling36. The natural crosslink chemistry present in oligomer, but not found in polymerizable monomeric collagens, is the primary contributor to the rapid scaffold-forming reaction as well as the improved mechanical integrity, slow metabolic turnover, and resistance to proteolytic degradation exhibited by oligomer scaffolds25,26,36. Collectively, these distinguishing features contribute to the uncommon mechanism of action and regenerative tissue response displayed by oligomer scaffolds when compared to conventional biodegradable collagen materials.

The ability to restore and regenerate tissue that is diseased, damaged, or dysfunctional has been one of the greatest challenges in medicine. In fact, researchers have been working to identify biomaterials and/or anti-inflammatory agents with the goal of achieving a more desirable healing outcome (i.e., regeneration) or biomaterial/device implant response47,48,49,50. For the breast, this challenge is particularly difficult, since it is comprised of multiple tissue types with distinct functions, including secretory (i.e., milk-producing) glands and ducts, supportive collagenous connective tissue, and volume-filling adipose tissue. At present, tissue engineering and regenerative medicine strategies for soft tissue and breast reconstruction remain in their infancy, with only a few strategies evaluated in large animal models to date (for reviews see49,50,51). The majority of approaches have focused on engineering adipose tissue from biologic or synthetic scaffolds, incorporating lipofilling, patient-derived cell populations, and growth factors to encourage adipogenesis and vascularization. For example, Santerre and co-workers developed a porous, biodegradable breast filler from polycarbonate-urethane for BCS applications. In a recent study, scaffold pellets designed with breast-like mechanical properties were used to fill lumpectomy cavities in mini-pigs. These scaffolds showed evidence of primarily an inflammatory cell infiltrate at 6 weeks, with 20–40% scaffold degradation and limited breast tissue regeneration at 9 months52. As an alternative approach, Hutmacher and co-workers are applying additive manufacturing techniques to create patient-specific polycaprolactone scaffolds for breast reconstruction. To improve adipose tissue generation, these scaffolds are implanted within the subglandular space of mini-pigs and allowed to accumulate fibrovascular tissue 2 weeks prior to injection of a lipoaspirate43. A major drawback to both of these synthetic scaffold approaches is the inability of the materials to signal cells, resulting in foreign body responses and slow cellularization and vascularization51.

In this study, porcine breasts varied in size and tissue composition, giving rise to consistency differences that were apparent both qualitatively and quantitatively. The measured compressive modulus range (approximately 6–19 kPa) encompassed breast consistencies observed in women, which reportedly ranges from 0.7 to 66 kPa depending on breast composition (e.g., fibroglandular versus fatty) and testing parameters (e.g., strain rate, preconditioning)53,54. The healing response of untreated breast defects was similar to that observed in women following BCS, yielding scar tissue that was structurally and functionally distinct from normal breast tissue. The 16-week longitudinal study showed progression through the classic overlapping phases of reparative wound healing that results in scarring, including hemostasis and inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling as shown in Fig. 8a. Substantial contraction of the defect, as evidenced by clip displacement and star-like scar tissue morphology, was facilitated by the initial fibrin clot and provisional matrix which are mechanically weak compared to normal breast ECM. The process of scar formation and remodeling over time is perhaps the most unpredictable and troubling aspect of BCS, since it is known to contribute to pain, distortions in the breast contour and consistency, and loss of sensation, all of which negatively affect women emotionally and psychologically55.

Timelines and processes of healing responses observed in porcine simulated lumpectomy model. Schematics comparing and contrasting the phases and processes associated with the (a) normal reparative response observed with no fill and the (b) proposed regenerative response observed with the collagen filler.

Filling the defect volume with a long-lasting fibrillar collagen, that is naturally metabolized and remodeled rather than actively degraded, resulted in a healing response where immune mediators were largely absent, and the outcome was more regenerative rather than reparative. Based on these results, the proposed regenerative healing response for the collagen filler is depicted in Fig. 8b. Since the injectable scaffold filled and conformed to defects and effectively integrated with surrounding host tissue, it re-established a structural and mechanical continuum across the tissue, which is known to be important to scar-free healing and tissue morphogenesis56,57. Notably, the compression modulus (7.67 ± 0.42 kPa) of the collagen filler fell within the range of both pig and human breast mechanical properties. The dense microstructure and compression properties of the collagen filler effectively resisted contraction forces exerted by the surrounding normal tissue as well as infiltrating cells. Additionally, since scaffold mechanical properties were similar to soft tissues, they did not yield any concerning palpable breast inconsistencies. From a translational perspective, this is important for patient satisfaction and comfort, as well as for maintaining the ability to detect recurrent cancer through palpation.

Because collagen fibrils contain multiple functional cellular and molecular binding domains58, the scaffold could effectively participate in both biochemical and mechanochemical signaling, as is performed by tissue ECMs. Unlike conventional implantable materials, the scaffold was initially populated by fibroblast-like mesenchymal cells, along with vessel-forming cells, rather than inflammatory mediators. The rapid and robust neovascularization response was consistent with other in vivo studies where oligomer has been implanted into other microenvironments27,29,30,31,32,33 and used for in vitro investigations of underlying mechanisms of vessel formation26,35,59. As these front-line cells progressed deeper toward the scaffold center with time, tissue neogenesis followed, with formation of adipose tissue and mammary glands, including secretory lobules and ducts. Interestingly, newly formed lobules, which were especially apparent at 4- and 16-week time points, were reminiscent of those found in nulliparous (pre-pregnancy) breasts since they were largely lacking in macrophage infiltration60. Collectively, the regenerative tissue response observed with the collagen fill has many similarities to processes associated with tissue development and morphogenesis, including mammary glands61, highlighting the importance of maintaining stromal collagen and its associated mechanobiological continuum.

As part of this study, we also documented that the collagen filler was not negatively impacted by radiation therapy and did not compromise interpretation of diagnostic imaging procedures. In the present study, irradiation was applied 2 weeks following simulated lumpectomy, which is within the range of adjuvant radiation administration following BCS. Tumors and tissues with rapid cell turnover, such as the epidermal layer of the skin, are most sensitive to irradiation effects, with the extent of damage depending on the total radiation dose and time over which the radiation is delivered62. Irradiation resulted in hyperpigmentation of skin, an expected side effect that is analogous to sunburn or tanning responses displayed in humans, as well as moderate levels of fat necrosis and hyperplasia of glands and ducts. For both collagen and no fill treated groups, the healing progressed similarly to respective non-irradiated groups; however, the healing rate appeared modestly slower based on breast consistency scores and histopathological analysis. Such results were not surprising since irradiation is known to cause delays in wound healing63. Based on combined histopathology, x-ray and ultrasound analyses, the collagen filler and its associated signaling capacity were determined to be largely unaffected by irradiation. Radiographs and ultrasonograms also indicated that the collagen fill yielded no suspicious artifacts. This has been a major drawback with fat grafting, where a wide spectrum of alterations in breast tissue have been detected via these diagnostic imaging techniques, ranging from benign-looking lipid cysts to findings suspicious for malignancy such as micro-calcification, focal masses, and speculated areas of increased opacity64,65.

Given that this work represented an early proof-of-principle evaluation, these studies are not without limitations. First, owing to breast size differences between pig and human, a quadrantectomy was performed with removal of roughly 25% pig breast volume. Defect volumes ranged from 2 to 5.5 mL, with an average defect volume of about 3 mL. While quadrantectomies are rarely, if ever, performed on women, these absolute defect volumes fell within the range of human clinical procedures. Specifically, published human clinical reports indicate that 67% and 82% of breast tumors are ≤ 1.9 cm (≤ 3.6 mL) and ≤ 2.9 cm (≤ 12.8 mL) in diameter (volume), respectively66. While additional studies are needed to determine how defect size affects material performance, no detrimental outcomes are anticipated based on observed material mode of action. However, it is anticipated that time to complete cellularization and healing would vary directly with defect volume. Second, since the longest timepoint evaluated was 16 weeks, additional animal and human clinical studies are needed to define long-term (i.e., 6 months or greater) collagen filler outcomes. A third limitation of these large-animal studies was that pigs were cancer free. As such, the effect of collagen filler on tumor promotion and recurrence cannot be fully evaluated. For a number of reasons, it is not anticipated that the collagen filler would pose a risk to oncologic safety. First, since breast surgeons would be able to more predictably maintain breast contour and consistency, they would have increased confidence about excising more tissue to achieve negative margins. We also show that the collagen filler induces no inflammatory or foreign body response, which is especially important since macrophage infiltration and other processes (e.g., cytokine release) associated with inflammation have been implicated in tumor promotion67,68,69. Additionally, when tested with various cancer cell types in vitro, high fibril density/stiffness of oligomer scaffolds was found to limit tumor cell proliferation and migration70. Finally, to further combat tumor recurrence, a chemotherapeutic or other anti-cancer agents could be readily added to the scaffold-forming reaction to achieve targeted and localized delivery. This would dramatically decrease the amount of drug administered and minimize side effects associated with systemic administration.

In conclusion, our work shows that a regenerative tissue filler that forms in situ and is fashioned from a natural collagen polymer appears to address surgeon needs and overcome major limitations associated with conventional implantable materials. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of a breast filler that persists, maintains its volume, and induces progressive breast tissue regeneration, including mammary glands, ducts, and adipose tissue. Additionally, study findings have important implications to regenerative medicine, suggesting that decreased inflammation and maintenance of a collagen structural and mechanical continuum tilts the healing balance from repair (scar formation) towards regeneration. This work sets the stage for future pre-clinical and clinical studies where the translation potential of this prototype regenerative tissue filler can be further validated for BCS and other soft tissue restoration and reconstruction needs.

Methods

Scaffold-forming Type I Collagen

The scaffold-forming collagen was obtained as a kit from GeniPhys (Zionsville, Indiana) as shown if Fig. 1a. The oligomeric collagen component of these kits was manufactured and quality-controlled from hides (dermis) of closed herd pigs in accordance with patented procedures and ASTM International F3089-14 guidelines for polymerizable collagens71,72. Two collagen formulations that differed by a single, proprietary manufacturing step were evaluated; however, since no difference in performance was observed, results were combined and presented as a single formulation. To evaluate collagen purity, sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) was performed on collagen samples and molecular weight standards (Novex SeeBlue Plus2, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) using 4–20% and 6% gels (Invitrogen) and stained with Coomassie Blue (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) according to established methods25. Collagen concentration was determined using a Sirius Red (Direct Red 80, Sigma-Aldrich) assay. Time-dependent oscillatory shear rheometry was performed to determine self-assembly kinetics and shear storage (G′) and loss (G″) moduli. Briefly, neutralized oligomeric collagen samples were tested on an AR2000 rheometer (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE), with a 40-mm parallel plate geometry and solvent trap. Prior to sample loading and during the first 2 min of testing, the Peltier plate was maintained at 4 °C. Oscillatory shear measurements were taken at 1% strain for this initial 2 min and continued for 10 min after the temperature was increased to 37 °C. Following oscillatory shear testing, the sample was subjected to unconfined compression testing at a strain rate of 20 µm/s. To define the kinetics of scaffold formation, a plot of shear storage modulus over time was created, and the time at which the collagen reached its maximum stiffness (G′) was defined as the polymerization time. This point was also used to define scaffold G′ and G″ values. To obtain the compression modulus, stress–strain curves were created from the unconfined compression data and the slope was calculated in a specified low strain region (20–40% strain), corresponding to the low stress/strain moduli that are reported in literature for human breast tissue54,73. Four independent batches of prototype collagens were tested with 6–8 replicates per batch (N = 4 batches; n = 6–8 replicates per batch).

Porcine simulated lumpectomy model

Simulated lumpectomies were performed on female Yucatan mini-pigs (retired breeders) weighing between 45 and 65 kg using a protocol that was approved by the Purdue Animal Care and Use Committee. All handling and care of animals was performed in accordance with relevant NIH and AAALAC guidelines. Prior to surgery, all of the breasts of an individual pig (12 breasts per pig) were randomly assigned to experimental (6 breasts per pig) and control groups, with no fill (3 breasts per pig) and no surgery (3 breasts per pig) serving as negative and positive controls, respectively. Animals were anesthetized, intubated, and placed in dorsal recumbency. For each simulated lumpectomy, a 3-cm skin incision was made using a scalpel, with incisions oriented transversely and placed immediately lateral to the nipple-areolar complex of each breast. Approximately one quarter of the mammary tissue was excised using electrocautery and its volume measured using a standard volume displacement method. A subset of excised normal mammary tissue was subjected to unconfined compression testing (strain rate: 1 mm/min, compression modulus determined in linear region of 20–40% strain) for characterization of mechanical properties. Titanium marker clips (Ethicon Small LIGACLIP, West CMR, Clearwater, FL) were placed in a subset of animals to facilitate margin identification of collagen and no fill treated surgical sites. For collagen-treated sites, the collagen solution and neutralization reagent were mixed according to instructions, and the resultant neutralized liquid collagen used to fill the surgical void. Negative control sites received no fill (untreated). A subset of pig breasts that were not subjected to surgery served as positive controls. All surgical sites were closed using resorbable sutures and bandaged with a non-adherent pad (McKesson, San Francisco, CA) and Tegaderm (3 M, St. Paul, MN) dressing. The animals’ health status was monitored daily based on appetite, attitude, movement, and elimination.

Longitudinal study

A longitudinal study was performed with post-surgical assessment performed at 1-, 4-, and 16-week time points (2 animals per time point) to achieve twelve replicates (n = 12) for the collagen filler group and six replicates (n = 6) for each the no fill and no surgery control groups.

Radiation study

To address the question of how radiation therapy affects the tissue response to collagen soft-tissue fillers, two animals were treated with radiation following simulated lumpectomy and treatment. Pig breasts were again randomly assigned to treatment groups, with no fill treatment and breasts on which no surgery was performed serving as negative and positive controls, respectively. Computed tomography (CT) based, three-dimensional conformal treatment (3D-CRT) plans were generated for each animal. Two weeks following surgery, a 6 MV Varian EX linear accelerator and 120-leaf multi-leaf collimator was used to apply 4 Gy radiation to the ventral surface daily for 5 days for a total dose of 20 Gy. Post-surgical assessments were performed 4 and 16 weeks following surgery with six replicates (n = 6) for the collagen filler group, three replicates (n = 3) for the no fill group, and one (n = 1) replicate for the no surgery group. The most caudal pair of mammary glands served as non-irradiated no surgery controls. Outcomes from irradiated animals were compared to non-irradiated animals from the longitudinal study.

Post-surgical procedures and assessment

At designated time points, the animals were anesthetized, and each breast evaluated using a semi-quantitative scoring system for gross breast/surgical site appearance, including erythema/eschar formation and edema formation, and breast uniformity/consistency scoring as shown in Supplementary Fig. S3. Additionally, ultrasound imaging of each mammary gland was performed with a Mindray M7 ultrasound machine (Mindray North America, Mahwah, NJ) and a linear 4–7 MHz transducer. Following euthanasia, a mastectomy was performed on each breast, maintaining all surgical sites, any implant, and the surrounding tissue. Each breast was placed in 10% buffered formalin and radiographed using an InnoVet Select Radiograph unit (Summit, Niles, IL) with a Genesis Vet DR plate installed using Genesis VxVue acquisition software (Genesis Digital Imaging, Los Angeles, CA), prior to processing for histopathological analysis. Formalin-fixed explanted tissues were bisected and imaged prior to paraffin embedding and sectioning. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). To detect epithelial cells, sections were stained for pan cytokeratin (ab9377, Abcam, Cambridge, MA) at a dilution of 1:100 and then treated with secondary DyLight 488 goat anti-rabbit (DI-1488, Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA) at 6 μg/mL. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (4′, 6-diamidino-2′-phenylindole, dihydrochloride; EN62248, Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL). Images were acquired using a Aperio VERSA 8 whole-slide scanner (Leica Biosystems, Buffalo Grove, IL).

Data availability

All data are included in this paper or the Supplementary Materials. Additional materials can be obtained by request to T.J.P. and S.V.-H. and may be subject to non-disclosure and material-transfer agreement requirement with GeniPhys.

References

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 68, 394–424 (2018).

American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2020 (American Cancer Society, Atlanta, 2020).

Fisher, B. et al. Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing total mastectomy, lumpectomy, and lumpectomy plus irradiation for the treatment of invasive breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 347, 1233–1241 (2002).

Van Dongen, J. A. et al. Long-term results of a randomized trial comparing breast-conserving therapy with mastectomy: European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer 10801 trial. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 92, 1143–1150 (2000).

NIH consensus conference. Treatment of early-stage breast cancer. JAMA 265, 391–395 (1991).

American Society of Breast Surgeons, "Performance and practice guidelines for breast-conserving surgery/partial mastectomy," (2015).

Nano, M. T. et al. Psychological impact and cosmetic outcome of surgical breast cancer strategies. ANZ J. Surg. 75, 940–947 (2005).

Hau, E. et al. The impact of breast cosmetic and functional outcomes on quality of life: long-term results from the St. George and Wollongong randomized breast boost trial. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 139, 115–123 (2013).

Anderson, B. O., Masetti, R. & Silverstein, M. J. Oncoplastic approaches to partial mastectomy: An overview of volume-displacement techniques. Lancet Oncol. 6, 145–157 (2005).

Waljee, J. F. et al. Effect of esthetic outcome after breast-conserving surgery on psychosocial functioning and quality of life. J. Clin. Oncol. 26, 3331–3337 (2008).

Metcalfe, L. N. et al. Beyond the margins-economic costs and complications associated with repeated breast-conserving surgeries. JAMA Surg. 152, 1084–1086 (2017).

Kaczmarski, K. et al. Surgeon re-excision rates after breast-conserving surgery: a measure of low-value care. J. Am. Coll. Surg. 228, 504–512 e502 (2019).

Vos, E. L. et al. Preoperative prediction of cosmetic results in breast conserving surgery. J. Surg. Oncol. 111, 178–184 (2015).

Vos, E. L. et al. A preliminary prediction model for potentially guiding patient choices between breast conserving surgery and mastectomy in early breast cancer patients: A Dutch experience. Qual. Life Res. 27, 545–553 (2018).

Gu, J. et al. Review of factors influencing women’s choice of mastectomy versus breast conserving therapy in early stage breast cancer: A systematic review. Clin. Breast Cancer 18, e539–e554 (2018).

Srour, M. K. & Chung, A. Utilization of BioZorb implantable device in breast-conserving surgery. Breast J. 26, 960–965 (2019).

Rashad, R., Huber, K. & Chatterjee, A. Cost-effectiveness of the Biozorb device for radiation planning in oncoplastic surgery. Cancer Clin. Oncol. 7, 23–32 (2018).

Tenofsky, P. L., Dowell, P., Topalovski, T. & Helmer, S. D. Surgical, oncologic, and cosmetic differences between oncoplastic and nononcoplastic breast conserving surgery in breast cancer patients. Am. J. Surg. 207, 398–402 (2014).

Groen, J. W. et al. Autologous fat grafting in onco-plastic breast reconstruction: A systematic review on oncological and radiological safety, complications, volume retention and patient/surgeon satisfaction. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 69, 742–764 (2016).

O'Halloran, N., Courtney, D., Kerin, M. J. & Lowery, A. J. Adipose-derived stem cells in novel approaches to breast reconstruction: their suitability for tissue engineering and oncological safety. Breast Cancer (Auckl) 11, 1–18 (2017).

Biazus, J. V. et al. Immediate reconstruction with autologous fat transfer following breast-conserving surgery. Breast J. 21, 268–275 (2015).

Biazus, J. V. et al. Breast-conserving surgery with immediate autologous fat grafting reconstruction: Oncologic outcomes. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 42, 1195–1201 (2018).

Stumpf, C. C. et al. Oncologic safety of immediate autologous fat grafting for reconstruction in breast-conserving surgery. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 180, 301–309 (2020).

Chatterjee, A. et al. A cost-utility analysis comparing oncoplastic breast surgery to standard lumpectomy in large breasted women. Adv. Breast Cancer Res. 7, 187–200 (2018).

Kreger, S. T. et al. Polymerization and matrix physical properties as important design considerations for soluble collagen formulations. Biopolymers 93, 690–707 (2010).

Bailey, J. L. et al. Collagen oligomers modulate physical and biological properties of three-dimensional self-assembled matrices. Biopolymers 95, 77–93 (2011).

Stephens, C. H. et al. In-situ type I oligomeric collagen macroencapsulation promotes islet longevity and function in vitro and in vivo. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 315, E650–E661 (2018).

Yrineo, A. A. et al. Murine ultrasound-guided transabdominal para-aortic injections of self-assembling type I collagen oligomers. J. Control Release 249, 53–62 (2017).

Stephens, C. H. et al. Oligomeric collagen as an encapsulation material for islet/β-cell replacement: Effect of islet source, dose, implant site, and administration format. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 319, E388–E400 (2020).

Sohutskay, D. O., Buno, K. P., Tholpady, S. S., Nier, S. J. & Voytik-Harbin, S. L. Design and biofabrication of dermal regeneration scaffolds: Role of oligomeric collagen fibril density and architecture. Regen. Med. 15, 1295–1312 (2020).

Brookes, S., Voytik-Harbin, S., Zhang, H. & Halum, S. Three-dimensional tissue-engineered skeletal muscle for laryngeal reconstruction. Laryngoscope 128, 603–609 (2018).

Brookes, S., Voytik-Harbin, S., Zhang, H., Zhang, L. & Halum, S. Motor endplate-expressing cartilage-muscle implants for reconstruction of a denervated hemilarynx. Laryngoscope 129, 1293–1300 (2019).

Brookes, S. et al. Laryngeal reconstruction using tissue engineered implants in pigs: A pilot study. Laryngoscope in press, (2020)

Critser, P. J., Kreger, S. T., Voytik-Harbin, S. L. & Yoder, M. C. Collagen matrix physical properties modulate endothelial colony forming cell-derived vessels in vivo. Microvasc. Res. 80, 23–30 (2010).

Whittington, C. F., Yoder, M. C. & Voytik-Harbin, S. L. Collagen-polymer guidance of vessel network formation and stabilization by endothelial colony forming cells in vitro. Macromol. Biosci. 13, 1135–1149 (2013).

Blum, K. M. et al. Acellular and cellular high-density, collagen-fibril constructs with suprafibrillar organization. Biomater. Sci. 4, 711–723 (2016).

Novak, T. et al. Mechanisms and microenvironment investigation of cellularized high density gradient collagen matrices via densification. Adv. Funct. Mater. 26, 2617–2628 (2016).

Stricker-Krongrad, A., Shoemake, C. R. & Bouchard, G. F. The miniature swine as a model in experimental and translational medicine. Toxicol. Pathol. 44, 612–623 (2016).

Ratner, B. D. Biomaterials: Been there, done that, and evolving into the future. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 21, 171–191 (2019).

Elsberger, B. et al. Comparison of mammographic findings after intraoperative radiotherapy or external beam whole breast radiotherapy. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. 40, 163–167 (2014).

Moore, G. H., Schiller, J. E. & Moore, G. K. Radiation-induced histopathologic changes of the breast: The effects of time. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 28, 47–53 (2004).

Findlay, M. W. et al. Tissue-engineered breast reconstruction: Bridging the gap toward large-volume tissue engineering in humans. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 128, 1206–1215 (2011).

Chhaya, M. P., Balmayor, E. R., Hutmacher, D. W. & Schantz, J. T. Transformation of breast reconstruction via additive biomanufacturing. Sci. Rep. 6, 28030 (2016).

Requena, L. et al. Adverse reactions to injectable soft tissue fillers. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 64, 1–34 (2011).

Pachence, J. M. Collagen-based devices for soft tissue repair. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 33, 35–40 (1996).

Eyre, D. R., Paz, M. A. & Gallop, P. M. Cross-linking in collagen and elastin. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 53, 717–748 (1984).

Vishwakarma, A. et al. Engineering immunomodulatory biomaterials to tune the inflammatory response. Trends Biotechnol. 34, 470–482 (2016).

Garash, R., Bajpai, A., Marcinkiewicz, B. M. & Spiller, K. L. Drug delivery strategies to control macrophages for tissue repair and regeneration. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood) 241, 1054–1063 (2016).

Donnely, E., Griffin, M. & Butler, P. E. Breast reconstruction with a tissue engineering and regenerative medicine approach (systematic review). Ann. Biomed. Eng. 48, 9–25 (2020).

Young, D. A. & Christman, K. L. Injectable biomaterials for adipose tissue engineering. Biomed. Mater. 7, 024104 (2012).

Visscher, L. E. et al. Breast augmentation and reconstruction from a regenerative medicine point of view: state of the art and future perspectives. Tissue Eng. Part B Rev. 23, 281–293 (2017).

Santerre, P., Sharif-poor, S. & Leong. L. Biodegradable soft tissue filler. WO 2017/139868 A1, published August 24, 2017.

Gefen, A. & Dilmoney, B. Mechanics of the normal woman’s breast. Technol. Health Care 15, 259–271 (2007).

Ramiao, N. G. et al. Biomechanical properties of breast tissue, a state-of-the-art review. Biomech. Model Mechanobiol. 15, 1307–1323 (2016).

Henderson, I. C. Breast Cancer: Fundamentals of Evidence-Based Disease Management. (Oxford University Press, 2015).

Dudas, M., Wysocki, A., Gelpi, B. & Tuan, T. L. Memory encoded throughout our bodies: Molecular and cellular basis of tissue regeneration. Pediatr. Res. 63, 502–512 (2008).

Guilak, F., Butler, D. L., Goldstein, S. A. & Baaijens, F. P. Biomechanics and mechanobiology in functional tissue engineering. J. Biomech. 47, 1933–1940 (2014).

Sweeney, S. M. et al. Candidate cell and matrix interaction domains on the collagen fibril, the predominant protein of vertebrates. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 21187–21197 (2008).

Buno, K. P. et al. In vitro multitissue interface model supports rapid vasculogenesis and mechanistic study of vascularization across tissue compartments. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8, 21848–21860 (2016).

Jindal, S. et al. Postpartum breast involution reveals regression of secretory lobules mediated by tissue-remodeling. Breast Cancer Res. 16, R31 (2014).

Maller, O., Martinson, H. & Schedin, P. Extracellular matrix composition reveals complex and dynamic stromal-epithelial interactions in the mammary gland. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 15, 301–318 (2010).

Ryan, J. L. Ionizing radiation: The good, the bad, and the ugly. J. Invest. Dermatol. 132, 985–993 (2012).

Jacobson, L. K., Johnson, M. B., Dedhia, R. D., Niknam-Bienia, S. & Wong, A. K. Impaired wound healing after radiation therapy: A systematic review of pathogenesis and treatment. JPRAS Open 13, 92–105 (2017).

Pulagam, S. R., Poulton, T. & Mamounas, E. P. Long-term clinical and radiologic results with autologous fat transplantation for breast augmentation: Case reports and review of the literature. Breast J. 12, 63–65 (2006).

Upadhyaya, V. S., Uppoor, R. & Shetty, L. Mammographic and sonographic features of fat necrosis of the breast. Indian J. Radiol. Imaging 23, 366–372 (2013).

Welch, H. G., Prorok, P. C., O’Malley, J. & Kramer, B. S. Breast-cancer tumor size, overdiagnosis, and mammography screening effectiveness. N Engl. J. Med. 375, 1438–1447 (2016).

O’Brien, J. et al. Alternatively activated macrophages and collagen remodeling characterize the postpartum involuting mammary gland across species. Am. J. Pathol. 176, 1241–1255 (2010).

Leek, R. D. et al. Association of macrophage infiltration with angiogenesis and prognosis in invasive breast carcinoma. Cancer Res. 56, 4625–4629 (1996).

Cassetta, L. et al. Human tumor-associated macrophage and monocyte transcriptional landscapes reveal cancer-specific reprogramming, biomarkers, and therapeutic targets. Cancer Cell 35, 588–602 (2019).

Puls, T. J. et al. Development of a novel 3D tumor-tissue invasion model for high-throughput, high-content phenotypic drug screening. Sci. Rep. 8, 13039 (2018).

Voytik-Harbin, S. L., Kreger, S., Bell, B. & Bailey, J, inventors; Purdue Research Foundation, assignee. Collagen preparation and method of isolation. U.S. Patent 8,084,055. December 27, 2011

ASTM International. ASTM Standard F3089: Standard guide for characterization and standardization of polymerizable collagen-based products and associated collagen-cell interactions (West Conshohocken, PA, 2014).

Umemoto, T. et al. Ex vivo and in vivo assessment of the non-linearity of elasticity properties of breast tissues for quantitative strain elastography. Ultrasound Med. Biol. 40, 1755–1768 (2014).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge assistance of V. Bernal-Crespo and the Purdue University Histology Research Laboratory, a core facility of the NIH-funded Indiana Clinical and Translational Sciences Institute, for preparation of histological slides. We also thank members of the Weldon School Preclinical Studies Research Team, including G. Brock, T. Cleary, S. Nier, and R. Seiber, for all their time and effort related to animal husbandry and the animal study. Finally, we thank S.A. Harbin for use of radiology facilities and assistance with obtaining radiographs.

Funding

This work was supported by NSF SBIR Phase I grant (1913626) awarded to GeniPhys (PI: T.J.P), with subcontracts to Purdue (PI: S.V.-H.) and Indiana University School of Medicine (PI: C.F.). E.M. is a trainee of the NIGMS-funded Indiana Medical Scientist/Engineer Training Program (T32 GM077229) and the recipient of a NIDDK-funded predoctoral fellowship (T32 DK101000).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.J.P. and S.V.-H. generated the concept. T.J.P., S.V.-H., C.F., and M.B. designed the in vivo and in vitro experiments. C.F. performed all simulated lumpectomy procedures and post-surgical breast assessments. T.J.P., E.M., T.M., and S.V.-H. assisted with surgical procedures and prepared explants. T.J.P., E.M., J.A., C.G. and S.V.-H. aided in the acquisition and interpretation of diagnostic imaging. J.P. developed and performed the radiation plan. A.C. performed all histopathological analyses. S.V.-H. and T.J.P. wrote the manuscript and all authors reviewed, provided comments, and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

S.V.-H. and T.J.P. are inventors on a patent application that covers the prototype soft tissue filler composition. S.V.-H. is inventor on issued and pending patents that cover base collagen oligomer technology. S.V.-H. is the Founder of GeniPhys, a start-up company who licensed the collagen polymer technology from Purdue Research Foundation for development and commercialization of regenerative medicine products. T.J.P. serves as the GeniPhys Product Development Manager. All other authors declare no competing interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Video 1.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Puls, T.J., Fisher, C.S., Cox, A. et al. Regenerative tissue filler for breast conserving surgery and other soft tissue restoration and reconstruction needs. Sci Rep 11, 2711 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-81771-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-81771-x

This article is cited by

-

Strategies for Constructing Tissue-Engineered Fat for Soft Tissue Regeneration

Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine (2024)

-

Overview of Oncoplastic Breast Surgery Techniques for the Treatment of Breast Cancer with Review of Normal and Abnormal Postsurgical Imaging Findings

Current Radiology Reports (2022)

-

Application of an ultrasound semi-quantitative assessment in the degradation of silk fibroin scaffolds in vivo

BioMedical Engineering OnLine (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.