Abstract

Loss of bone mineral density (BMD) is a substantial risk of mortality in addition to fracture in hemodialysis patients. However, the factors affecting BMD are not fully determined. We conducted a single-center, cross-sectional study on 321 maintenance hemodialysis patients who underwent evaluation of femoral neck BMD using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry from August 1, 2018, to July 31, 2019. We examined factors associated with osteoporosis defined by T-score of ≤ − 2.5, using logistic regression models. Median age of patients was 66 years, and 131 patients (41%) were diagnosed with osteoporosis. Older age, female, lower body mass index, diabetes mellitus, and higher Kt/V ratios were associated with higher osteoporosis risk. The only medication associated with lower osteoporosis risk was calcium-based phosphate binders (CBPBs) [odds ratio (OR), 0.41; 95% confidence interval (CI), 0.21–0.81]. In particular, CBPB reduced the osteoporosis risk within subgroups with dialysis vintage of ≥ 10 years, albumin level of < 3.5 mg/dL, active vitamin D analog use, and no proton pump inhibitor (PPI) use. In conclusion, CBPB use was associated with lower osteoporosis risk in hemodialysis patients. This effect might be partially attributable to calcium supplementation, given its higher impact in users of active vitamin D analogs or non-users of PPI, which modulate calcium absorption.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Osteoporosis is characterized by reduced bone mineral density (BMD) and microarchitectural deterioration of bone tissue, leading to bone fragility and a consequent increase in the risk of fractures1,2. Bone disease is a common complication in patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), and such a condition is referred to as CKD mineral and bone disease (CKD–MBD). According to Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines, CKD–MBD is a systemic disorder of mineral and bone metabolism due to CKD manifested by either one or a combination of the following: (1) abnormalities of calcium, phosphorus, intact parathyroid hormone (PTH), or vitamin D metabolism; (2) abnormalities in bone turnover, mineralization, volume, linear growth, or strength; or (3) vascular or other soft-tissue calcification. Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey have suggested that CKD and osteoporosis are highly coprevalent3,4 .

The incidence of fractures progressively increases according to CKD progression, and patients with CKD, particularly those with end-stage disease, have a high risk of fractures, which leads to unfavorable morbidity and mortality5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12. In the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study report including an international cohort of hemodialysis patients, the incidence of fractures was reported to be significantly higher for hemodialysis patients than for the general population, with a 3.7-fold increase in the unadjusted relative risk of mortality8. Furthermore, a more recent study including a Japanese cohort reported that the mortality rate after fractures was 4.8-fold higher in hemodialysis patients than in the general population11. Therefore, it is essential to prevent osteoporosis and fractures to improve the outcome of patients with ESKD.

Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) is a well-established tool for measuring BMD and strongly predicting the risk of fracture13,14. Accumulating evidence has revealed that DXA-based BMD predicts the risk of incident fractures in patients with advanced CKD, including hemodialysis patients, similar to that observed in the general population15,16,17,18. The latest KDIGO 2017 CKD–MBD guidelines recommend measurements of BMD in patients with advanced CKD. More recently, decreased DXA-based BMD was shown to predict a higher risk of overall mortality in patients with ESKD12. However, factors or medications that improve osteoporosis in this population have not been fully clarified because of the limited number of studies reported in the literature regarding factors associated with BMD in a large number of participants.

Therefore, the present study aimed to investigate clinical factors and medications, particularly including CKD–MBD-related medications, that are associated with BMD in maintenance hemodialysis patients using DXA.

Material and methods

Study design and participants

This is a single-center, cross-sectional study including 321 maintenance hemodialysis patients who underwent evaluations of femoral neck BMD using DXA from August 1, 2018, to July 31, 2019, at our dialysis center. Patients aged > 80 years or those who lacked routine laboratory data were excluded. All the patients received hemodialysis three times per week. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Shuuwa General Hospital, and the study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki guidelines regarding ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Informed consent was obtained from all participants after information about the study.

Data collection

Baseline demographics and characteristics were recorded for each patient. Laboratory tests were performed in the first dialysis session of each week. We analyzed laboratory data measured within 1 month before DXA measurements, including serum albumin, sodium, calcium, phosphate, and urea nitrogen levels. In addition, we analyzed the plasma-intact PTH levels measured within 3 months before DXA measurements. Kt/V (Kt/V is a number used to quantify hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis treatment adequacy) ratios were calculated using the single-pool Daugirdas formula. Geriatric nutritional risk index (GNRI) is a nutritional marker calculated by serum albumin level and body mass index (BMI)19. Percent creatinine generation rate (%CGR) is used as estimates of muscle mass and protein nutritional status20. Cardiovascular disease (CVD) was defined as any of the following: stroke, ischemic heart disease, congestive heart failure, or peripheral arterial disease. Hypertension was defined as a systolic blood pressure of ≥ 140 mmHg, a diastolic blood pressure of ≥ 90 mmHg, or taking antihypertensive agents. Diabetes mellitus was defined as hemoglobin A1C of ≥ 6.5%. Medication-related data and use of CBPBs, oral or IV-active vitamin D analogs, oral or IV calcimimetics, and PPIs were recorded. BMD was measured by DXA using a Horizon WI Bone Densitometer (Hologic Inc, Marlborough, Mass, USA). The results were expressed in terms of T-scores and standard deviation (SD) compared with healthy young sex-matched controls. Osteoporosis was defined as a T-score of ≤ − 2.5 according to the World Health Organization definition.

Statistical analyses

Continuous data are shown as means with SD or medians with interquartile ranges (IQR), as appropriate. Categorical variables are expressed as numbers and percentages. Comparisons between the osteoporosis and non-osteoporosis groups were performed using the unpaired t test or Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables and the chi-squared test for categorical variables, as appropriate. Multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to evaluate factors associated with the risk of osteoporosis. Estimates of association were expressed as odds ratios (ORs) with the corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI). Subgroup analysis using multiple logistic regression analyses were performed to evaluate the effects of CBPBs on BMD under specific factors or backgrounds. Univariate and multivariate linear regression analyses were performed to examine the relevant factors associated with BMD. All statistical analyses were performed using EZR (Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan), which is a graphical user interface for R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria)21. P values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 321 participants were enrolled in the study. Baseline characteristics and demographics of these patients are shown in Table 1. The median age was 66 years (IQR, 55–72 years), median dialysis vintage was 9 years (IQR, 5–17 years), 109 (34%) patients were women,138 (43%) were diagnosed with CVD, and 146 (46%) had diabetes mellitus. Osteoporosis was diagnosed in 131 (41%) patients. The median age was higher, the proportion of women was higher, and mean BMI was lower in the osteoporosis group than in the non-osteoporosis group. Median dialysis vintage and the prevalence of comorbidities such as CVD, hypertension, and diabetes mellitus were not significantly different in the two groups. With regard to laboratory data, mean serum phosphate levels and Kt/V ratios were higher in the osteoporosis group, whereas serum albumin, serum calcium, and serum intact PTH levels were not significantly different. The proportion of CBPB users was higher in the osteoporosis group, whereas the proportion of calcium-free phosphate binder, calcimimetics, and PPI users was not significantly different between the groups.

Factors associated with osteoporosis in hemodialysis patients

To elucidate factors associated with low BMD, multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed. As shown in Table 2, older age, female sex, lower BMI, diabetes mellitus, lower serum phosphate level, and higher Kt/V ratios were associated with an increased risk of osteoporosis. Conversely, the use of CBPBs was associated with a decreased risk of osteoporosis after adjustment of potential confounders. The use of CBPBs, active vitamin D analogs, and PPI was not significantly associated with BMD.

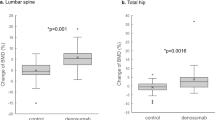

We further examined the association between covariates and DXA-based BMD using multivariate linear regression analysis. Older age, female sex, lower BMI, diabetes mellitus, lower serum calcium level, and higher Kt/V ratios were associated with lower BMD (Table 3). The use of CBPBs was associated with a higher BMD, as revealed by univariate and multivariate analyses. In addition to these analyses using a T-score, we also examined the BMD values based on absolute measurement (g per cm2). As shown in the Supplementary Figure 1, the BMD values were greater in CBPB users than non-CBPB users particularly among male patients. The univariate and multivariate linear regression analyses revealed the factors associated with BMD (Supplementary Table 1), which was very similar to those observed in the analysis using a T-score (Table 3). CBPB use was significantly associated with greater BMD in a univariate linear regression model, and this association was also marginally significant after adjusting for multiple cofounders.

Subgroup analysis

To evaluate the benefits of CBPBs in treating osteoporosis in the specific population with ESKD, we used the association between CBPBs and the risk for osteoporosis in various subgroups based on multivariate logistic regression models. As shown in Fig. 1, CBPB was particularly associated with a decreased risk of osteoporosis in patients with longer hemodialysis vintage, lower serum albumin level, lower intact PTH level, and active vitamin D analog use as well as in non-CVD, non-diabetes mellitus, and non-PPI use patients.

To further determine if impact of CBPBs on osteoporosis risk is related to the patients’ nutritional status, we performed the additional subgroup analysis with the widely used nutritional status indicators GNRI and %CGR19,20. As shown in the Supplementary Figure 2, CBPBs were significantly associated with lower risk of osteoporosis in the lower GNRI or %CGR subgroups, which might reflect lower intake of dietary calcium.

Discussion

This study investigated the association of multiple factors and medications with DXA-based BMD in maintenance hemodialysis patients and identified CBPB as a factor associated with a lower risk of osteoporosis in addition to the conventional risk factors for osteoporosis, including older age, female sex, lower BMI, diabetes mellitus, and higher Kt/V ratio. Moreover, we determined that the impact of CBPBs on BMD was greater in users of active vitamin D analogs or non-users of PPI, which modulate calcium absorption, suggesting that calcium supplementation by CBPBs increases BMD in patients with ESKD. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to report the beneficial effects of CBPBs on osteoporosis in patients with ESKD, providing new insights into osteoporosis treatment in this population.

The present study demonstrated that older age, female sex, lower BMI, and diabetes mellitus were correlated with lower BMD; these are well-established risk factors for osteoporosis in both the general population and patients with ESKD22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29. The association between higher Kt/V ratios and lower BMD demonstrated in the present study was unexpected, although the previous study including a large cohort of hemodialysis patients revealed that patients with fractures had higher Kt/V ratios8. In addition, we investigated the impact of medications, including CKD–MBD-related medications and PPI that is a recently identified risk factor for osteoporosis in adults and children30, on BMD and identified the previously unrecognized association between CBPB use and the decreased risk of osteoporosis.

It has long been unidentified whether CKD–MBD-related medications, including phosphate binders, modulate BMD and the subsequent risk of fracture in patients with ESKD. Recently, a prospective cohort study including 537 children with CKD reported that CBPBs reduced the risk of fractures31. A previous systematic review evaluating the effect of various phosphate binders on CKD–MBD-related outcomes of adult patients with CKD failed to conclude whether CBPB prevents fractures, possibly due to the enrollment of only one small randomized controlled trial based on 148 moderately ill patients with CKD32,33. A recent Korean population-based cohort study demonstrated that phosphate binders, including both CBPBs and non-CBPBs, reduced the risk of fractures in patients with ESKD34. The majority of phosphate binder users in this study were taking CBPBs, suggesting that the beneficial effect of phosphate binders was attributable to CBPBs and its favorable impact on BMD.

Calcium carbonate is the most used phosphate binder in patients with ESKD and is also used as a calcium supplement in the general population worldwide because of its cost efficiency and relatively high elemental calcium content. Although it is important to avoid excess calcium intake and prevent the increased risk of CVD events, kidney stones, and gastrointestinal symptom, adequate calcium intake is recommended for skeletal health in all age groups because long-term calcium deficiency can lead to osteoporosis and an increased risk of fracture35,36,37,38,39,40. However, several studies have indicated that the calcium intake in patients with CKD is basically low compared with the value recommended by dietary intake guidelines41,42. Thus, modest supplementation of calcium from foods, supplements, and calcium-containing medications, including CBPBs, is recommended for patients with CKD to achieve an estimated neutral calcium balance43. We speculated that calcium supplementation is among the major factors contributing to the increase in BMD in hemodialysis patients taking CBPBs, and the greater benefit of CBPBs among the subgroups with unfavorable nutritional status in our analyses support this speculation.

CBPBs were more likely to decrease the risk of osteoporosis, particularly in users of active vitamin D analogs and non-users of PPI, as revealed by our subgroup analysis. Vitamin D is also essential to bone health because it promotes intestinal calcium absorption. The efficacy of vitamin D alone or with concomitant use of calcium on osteoporosis and fractures has been examined in several trials in the general population. These trials revealed that vitamin D alone was insufficient but its concomitant use with calcium reduced the risk of fractures44,45,46,47,48. Considering these findings, we speculate that sufficient intake and adsorption of calcium is essential to prevent fractures, independent of the evidence of CKD. Furthermore, we demonstrated that CBPBs were less effective on BMD in PPI users.

Several studies, including a meta-analysis of case–control and cohort studies, have reported that PPIs are positively associated with an increased risk of fracture30,49,50,51,52,53. One possible explanation for this observation has been proposed: PPIs inhibit gastric acid, leading to impaired absorption of calcium54,55,56. Thus, this finding also supports the fact that calcium supplementation by CBPBs is partially responsible for increased BMD. We also demonstrated that CBPBs were effective in patients with reduced serum albumin level, lower BMI, and longer dialysis vintage. These results might be associated with the reduced nutrient intake, including calcium, in such patients. CBPBs were less effective in the CVD and diabetes mellitus groups. It is possible that a substantial proportion of these patients use loop diuretics, which increase calcium excretion.

Since excess of calcium intake might be harmful to CKD patients, the latest KDIGO guideline suggested restricting the dose of CBPBs among phosphate binders57. CBPB use is not associated with increase in mortality and vascular event risk compared with placebo in CKD patients. When compared with a calcium-free phosphate binder sevelamer, several clinical trials reported that CBPBs were associated with increased risk of vascular calcification58,59,60,61. However, the causal relationship between CBPBs and risk of mortality or cardiovascular events has yet to be determined, because “none of the studies provided sufficient dose threshold information about calcium exposure”57. Sevelamer is known to suppress vascular calcification due to mechanisms unrelated to calcium exposure such as improvement of the lipid profile, reduction of inflammation and oxidative stress57,62,63. The previous systematic review also demonstrated that risks of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, stroke, and coronary artery calcium score progression were not significantly different between a sevelamer and CBPBs, while risk of all-cause mortality was higher on CBPB use32. The findings in this study would provide novel insights into the association between CBPBs and CKD patients’ outcome, and indicate that CBPBs are potentially beneficial for bone health under avoidance of excessive calcium intake and adverse events. Further studies are needed to clarify the specific population who could receive therapeutic benefits of CBPBs.

The present study has several limitations. First, this was a single-center observational study. Second, because of the cross-sectional observational nature of this study, we could not establish causality. Third, data (such as serum bone alkaline phosphatase levels) regarding factors associated with bone metabolism were not available. Fourth, our dataset lacked diet inquiry or urinary calcium excretion that might be a nutritional marker of calcium intake, although urinary calcium may not reflect the dietary intake as the median dialysis vintage was nine years and 90% or more of the study participants were anuric or oliguric. Thus, we performed a subgroup analysis using the other nutritional status indicators GNRI and %CGR, and showed the higher impact of CBPBs on BMD under unfavorable nutritional status. Further investigations are warranted to establish the causal relationship between the use of CBPB and the prevention of osteoporosis and fractures.

Conclusion

We have demonstrated that oral CBPB use was associated with a lower risk of osteoporosis in maintaining hemodialysis patients. The study findings might provide novel insights into osteoporosis treatment in patients with ESKD.

References

Compston, J. E., McClung, M. R. & Leslie, W. D. Osteoporosis. Lancet 393, 364–376 (2019).

Consensus A. Consensus development conference: Diagnosis, prophylaxis, and treatment of osteoporosis. Am. J. Med. 94, 646–650 (1993).

Klawansky, S. et al. Relationship between age, renal function and bone mineral density in the US population. Osteoporos. Int. 14, 570–576 (2003).

Nickolas, T. L., McMahon, D. J. & Shane, E. Relationship between moderate to severe kidney disease and hip fracture in the United States. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 17, 3223–3232 (2006).

Coco, M. & Rush, H. Increased incidence of hip fractures in dialysis patients with low serum parathyroid hormone. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 36, 1115–1121 (2000).

Alem, A. M. et al. Increased risk of hip fracture among patients with end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int. 58, 396–399 (2000).

Jadoul, M. et al. Incidence and risk factors for hip or other bone fractures among hemodialysis patients in the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study. Kidney Int. 70, 1358–1366 (2006).

Tentori, F. et al. High rates of death and hospitalization follow bone fracture among hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 85, 166–173 (2014).

Lin, J. C. F. & Liang, W. M. Mortality and complications after hip fracture among elderly patients undergoing hemodialysis. BMC Nephrol. 16, 1–9 (2015).

Hickson, L. T. J. et al. Death and postoperative complications after hip fracture repair: Dialysis effect. Kidney Int. Rep. 3, 1294–1303 (2018).

Mandai, S., Sato, H., Iimori, S., Naito, S. & Tanaka, H. Nationwide in-hospital mortality following major fractures among hemodialysis patients and the general population: An observational cohort study. Bone 130, 115122 (2020).

Iseri, K. et al. Bone mineral density at different sites and 5 years mortality in end-stage renal disease patients: A cohort study. Bone 130, 115075 (2020).

Marshall, D., Johnell, O. & Wedel, H. Meta-analysis of how well measures of bone mineral density predict occurrence of osteoporotic fractures. BMJ 312, 1254–1259 (1996).

Johnell, O. et al. Predictive value of BMD for hip and other fractures. J. Bone Miner. Res. 20, 1185–1194 (2005).

West, S. L. et al. Bone mineral density predicts fractures in chronic kidney disease. J. Bone Miner. Res. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.2406 (2015).

Iimori, S. et al. Diagnostic usefulness of bone mineral density and biochemical markers of bone turnover in predicting fracture in CKD stage 5D patients—A single-center cohort study. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant 27, 345–351 (2012).

Naylor, K. L. et al. Comparison of fracture risk prediction among individuals with reduced and normal kidney function. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 10, 646–653 (2015).

Yenchek, R. H. et al. Bone mineral density and fracture risk in older individuals with CKD. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 7, 1130–1136 (2012).

Yamada, K. et al. Simplified nutritional screening tools for patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 87, 106–113 (2008).

Shinzato, T. et al. New method to calculate creatinine generation rate using pre- and postdialysis creatinine concentrations. Artif. Organs 21, 864–872 (1997).

Kanda, Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant. 48, 452–458 (2013).

Kanis, J. A. et al. Ten year probabilities of osteoporotic fractures according to BMD and diagnostic thresholds. Osteoporos. Int. 12, 989–995 (2001).

Ensrud, K. E., Cauley, J., Lipschutz, R. & Cummings, S. R. Weight change and fractures in older women. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Arch. Intern. Med. 157, 857–863 (1997).

Ensrud, K. E. et al. Body size and hip fracture risk in older women: A prospective study. Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Am. J. Med. 103, 274–280 (1997).

Langlois, J. A. et al. Hip fracture risk in older white men is associated with change in body weight from age 50 years to old age. Arch. Intern. Med. 158, 990–996 (1998).

Green, A. D., Colón-Emeric, C. S., Bastian, L., Drake, M. T. & Lyles, K. W. Does this woman have osteoporosis?. JAMA 292, 2890–2900 (2004).

Jia, P. et al. Risk of low-energy fracture in type 2 diabetes patients: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Osteoporos. Int. 28, 3113–3121 (2017).

Moayeri, A. et al. Fracture risk in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and possible risk factors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 13, 455–468 (2017).

Ni, Y. & Fan, D. Diabetes mellitus is a risk factor for low bone mass-related fractures: A meta-analysis of cohort studies. Medicine 96, e8811 (2017).

Wang, Y.-H., Wintzell, V., Ludvigsson, J. F., Svanström, H. & Pasternak, B. Association between proton pump inhibitor use and risk of fracture in children. JAMA Pediatr. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.0007 (2020).

Denburg, M. R. et al. Fracture burden and risk factors in childhood CKD: Results from the CKiD cohort study. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 27, 543–550 (2016).

Ruospo, M. et al. Phosphate binders for preventing and treating chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD). Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 8(8), CD006023 (2018).

Block, G. A. et al. Effects of phosphate binders in moderate CKD. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 23, 1407–1415 (2012).

Kwon, Y. E., Choi, H. Y., Kim, S., Ryu, D. R. & Oh, H. J. Fracture risk in chronic kidney disease: A Korean population-based cohort study. Kidney Res. Clin. Pract. 38, 220–228 (2019).

Dawson-Hughes, B. Calcium insufficiency and fracture risk. Osteoporos. Int. 6(Suppl 3), 37–41 (1996).

Warensjö, E. et al. Dietary calcium intake and risk of fracture and osteoporosis: Prospective longitudinal cohort study. BMJ 342, 1–9 (2011).

Jackson, R. D. et al. Calcium plus vitamin D supplementation and the risk of fractures. N. Engl. J. Med. 354, 669–683 (2006).

Li, K., Kaaks, R., Linseisen, J. & Rohrmann, S. Associations of dietary calcium intake and calcium supplementation with myocardial infarction and stroke risk and overall cardiovascular mortality in the Heidelberg cohort of the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition study (EPIC-Hei). Heart 98, 920–925 (2012).

Xiao, Q. et al. Dietary and supplemental calcium intake and cardiovascular disease mortality: The National Institutes of Health-AARP diet and health study. JAMA Intern. Med. 173, 639–646 (2013).

Lewis, J. R., Zhu, K. & Prince, R. L. Adverse events from calcium supplementation: Relationship to errors in myocardial infarction self-reporting in randomized controlled trials of calcium supplementation. J. Bone Miner. Res. 27, 719–722 (2012).

Martins, A. M. et al. Food intake assessment of elderly patients on hemodialysis. J. Ren. Nutr. 25, 321–326 (2015).

Fassett, R. G., Robertson, I. K., Geraghty, D. P., Ball, M. J. & Coombes, J. S. Dietary intake of patients with chronic kidney disease entering the LORD trial: Adjusting for underreporting. J. Ren. Nutr. 17, 235–242 (2007).

Hill Gallant, K. M. & Spiegel, D. M. Calcium balance in chronic kidney disease. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 15, 214–221 (2017).

Bolland, M. J. et al. Calcium intake and risk of fracture: Systematic review. BMJ 351, h4580 (2015).

DIPART (Vitamin D Individual Patient Analysis of Randomized Trials) Group. Patient level pooled analysis of 68 500 patients from seven major vitamin D fracture trials in US and Europe. BMJ 340, b5463 (2010).

Avenell, A., Mak, J. C. S. & O’connell, D. Vitamin D and vitamin D analogues for preventing fractures in post-menopausal women and older men. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2014(4), CD000227 (2014).

Bolland, M. J., Grey, A. & Avenell, A. Effects of vitamin D supplementation on musculoskeletal health: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and trial sequential analysis. Lancet. Diabetes Endocrinol. 6, 847–858 (2018).

Yao, P. et al. Vitamin D and calcium for the prevention of fracture: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw. Open 2, e1917789 (2019).

Yu, E. W., Bauer, S. R., Bain, P. A. & Bauer, D. C. Proton pump inhibitors and risk of fractures: A meta-analysis of 11 international studies. Am. J. Med. 124, 519–526 (2011).

Ngamruengphong, S., Leontiadis, G. I., Radhi, S., Dentino, A. & Nugent, K. Proton pump inhibitors and risk of fracture: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 106, 1209–1218 (2011). (quiz 1219).

Khalili, H. et al. Use of proton pump inhibitors and risk of hip fracture in relation to dietary and lifestyle factors: A prospective cohort study. BMJ 344, e372 (2012).

Kwok, C. S., Yeong, J.K.-Y. & Loke, Y. K. Meta-analysis: Risk of fractures with acid-suppressing medication. Bone 48, 768–776 (2011).

Liu, J. et al. Proton pump inhibitors therapy and risk of bone diseases: An update meta-analysis. Life Sci. 218, 213–223 (2019).

Recker, R. R. Calcium absorption and achlorhydria. N. Engl. J. Med. 313, 70–73 (1985).

Yu, E. W. et al. Acid-suppressive medications and risk of bone loss and fracture in older adults. Calcif. Tissue Int. 83, 251–259 (2008).

O’Connell, M. B., Madden, D. M., Murray, A. M., Heaney, R. P. & Kerzner, L. J. Effects of proton pump inhibitors on calcium carbonate absorption in women: A randomized crossover trial. Am. J. Med. 118, 778–781 (2005).

Isakova, T. et al. KDOQI US Commentary on the 2017 KDIGO clinical practice guideline update for the diagnosis, evaluation, prevention, and treatment of chronic kidney disease-mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD). Am. J. Kidney Dis. 70, 737–751 (2017).

Qunibi, W. et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of calcium acetate on serum phosphorus concentrations in patients with advanced non-dialysis-dependent chronic kidney disease. BMC Nephrol. 12, 9 (2011).

Chertow, G. M., Burke, S. K., Raggi, P. & for the Treat to Goal Working Group. Sevelamer attenuates the progression of coronary and aortic calcification in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 62, 245–252 (2002).

Chertow, G. M. et al. Determinants of progressive vascular calcification in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 19, 1489–1496 (2004).

Block, G. A. et al. Effects of sevelamer and calcium on coronary artery calcification in patients new to hemodialysis. Kidney Int. 68, 1815–1824 (2005).

Chertow, G. M. Slowing the progression of vascular calcification in hemodialysis. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 14, 310S – 314 (2003).

Ohtake, T. & Kobayashi, S. Impact of vascular calcification on cardiovascular mortality in hemodialysis patients: Clinical significance, mechanisms and possible strategies for treatment. Ren. Replace. Ther. 3, 13 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all study participants and staff who supported patient care and this study at our dialysis center.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grants from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. We received research grant support from Kyowa Hakko Kirin Co., Ltd., Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., and Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (to S.U.); yet, no funders had role in the conceptualization, design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, writing, or publication of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.H.: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing-original draft, visualization. S.S.: data curation. S.M.: conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing-review and editing, visualization, project administration, supervision. S.A., and S.U.: project administration, writing-review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hashimoto, H., Shikuma, S., Mandai, S. et al. Calcium-based phosphate binder use is associated with lower risk of osteoporosis in hemodialysis patients. Sci Rep 11, 1648 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-81287-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-81287-4

This article is cited by

-

The Bone-Vascular Axis in Chronic Kidney Disease: From Pathophysiology to Treatment

Current Osteoporosis Reports (2024)

-

Calcium-based phosphate binders and bone mineral density in patients undergoing hemodialysis: a retrospective cohort study

Clinical and Experimental Nephrology (2024)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.