Abstract

The infectious disease (COVID-19) causes serious damages and outbreaks. A large number of infected people have been reported in the world. However, such a number only represents those who have been tested; e.g. PCR test. We focus on the infected individuals who are not checked by inspections. The susceptible-infected-recovered (SIR) model is modified: infected people are divided into quarantined (Q) and non-quarantined (N) agents. Since N-agents behave like uninfected people, they can move around in a stochastic simulation. Both theory of well-mixed population and simulation of random-walk reveal that the total population size of Q-agents decrease in spite of increasing the number of tests. Such a paradox appears, when the ratio of Q exceeds a critical value. Random-walk simulations indicate that the infection hardly spreads, if the movement of all people is prohibited ("lockdown"). In this case the infected people are clustered and locally distributed within narrow spots. The similar result can be obtained, even when only non-infected people move around. However, when both N-agents and uninfected people move around, the infection spreads everywhere. Hence, it may be important to promote the inspections even for asymptomatic people, because most of N-agents are mild or asymptomatic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The infectious disease (COVID-19) caused by the coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) is spreading to a large number of individuals1,2,3. According to the WHO report, many people died by COVID-194. It is an urgent worldwide issue to break the chain of COVID-19 infection. Two major protection approaches are known: prevention and isolation. The former is a prepared protection for a person, such as masks and hand-washing. Vaccination has been thought to be the most effective method of prevention5,6. In contrast, the isolation (or segregation) means the cut-off of contact between infected and non-infected people. An example is quarantine to put an infected person into hospital. Another example is lockdown: mobilities of people are prohibited7,8. Very recently, vaccination is found to be the most effective method for COVID-196,9. However, in England, Republic of Chile and State of Arizona, the infection is widespread, even though the vaccination rate is above 40%4,6. Moreover, much time is still needed for vaccines to become widespread. Various types of infection control measures will be necessary.

We apply agent-based model (ABM) used in complex systems10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17. For infectious diseases, ABM is one of fundamental tools18,19,20. The epidemic spreading on lattices and networks have been studied by many authors20,21,22,23,24,25. In the present article, we explore the effect of mobility (random walk) on the isolation of infectious people. Infected people are divided into two groups, quarantined (Q) and non-quarantined (N) agents. The former can be detected by inspections; e.g. PCR test.

A certain proportion of infected people become severe, such as pneumonia3,26. In many countries, hospital beds are very crowded. To suppress the epidemic spreading, it should be important to quarantine the infected individuals. From the early stage of the epidemic, the importance of asymptomatic infection has been pointed out because the asymptomatic patient also behaves as a cryptic source of spreading infection27. Thus, a large number of people have being inspected by PCR test in the world. However, the application of PCR test for no symptom person has been restricted in Japan because the medical diagnostic PCR test resources were too poor to promote the test in the early period of the epidemic. Major academic societies in Japan claimed that PCR testing was basically not recommended for asymptomatic or mildly ill individuals28. Such claims raise some problems. (1) Is it okay to leave the infected person unchecked? (2) Does the number of Q-agents (PCR-positive) always increase with the number of tests? It has been reported for COVID-19 that most infected people have mild or no symptoms3,29. Because such people behave like uninfected people, they have considerably high infectivity30,31,32,33. This may be a distinct feature of COVID-19 never observed for the previous coronaviruses, SARS and MERS. We carry out simulations of random walk to report N-agents play a major role for epidemic spreading.

So far, various epidemic models have been presented for analyzing an epidemic spread34,35,36,37. In most cases, the epidemic of influenza and other infectious diseases has been theoretically explained by SIR model38,39,40,41 that considers susceptible (S), infected (I), and recovered (R) people. Interactions are represented as follows:

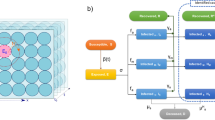

where β and γ represent infection and recovery rates, respectively. The spatial and network versions of SIR model is studied extensively in various fields42,43,44,45,46. In the present paper, we modify the SIR model as shown in Fig. 1a. Infected people are divided into quarantined (Q) and non-quarantined (N) agents. Similarly, the recovered (plus dead) people are also divided into \({\mathrm{R}}_{\mathrm{Q}}\) and \({\mathrm{R}}_{\mathrm{N}}\). Such a division may give us valuable information, because only the population size of Q (or \({\mathrm{R}}_{\mathrm{Q}}\)) is announced in public. It is important to know the behavior of N.

Model and population dynamics. (a) Schematic illustrations of infection model. (b) Predictions of mean-field theory (MFT) which agree with the simulation results of global interaction. In the present article, we put \({\rho }_{0}=0.2\) and the initial condition is set as follows: (S, N) = (0.792, 0.008) and the other densities are zero at t = 0. Values of parameters in all figures are listed in Table S1.

Method

We study epidemic spreading on a lattice. Each cell is either empty (O) or occupied by an individual (agent). The agent takes one of five states: S, Q, N, \({\mathrm{R}}_{\mathrm{Q}}\) and \({\mathrm{R}}_{\mathrm{N}}\). Symbols and parameters are listed in Table 1. Interactions are represented as follows:

where \(i\) denotes an infected agent (\(i=\mathrm{N},\mathrm{ Q}\)). The parameters \({\beta }_{\mathrm{i}}\) and \({\gamma }_{\mathrm{i}}\) denotes the infection and recovery rates of \(i\), respectively. We introduce "quarantine ratio" \(q\) which denotes the ratio of Q among all infected agents (see Fig. 1a). If \(q=1\), every infected agent is confirmed to be infected by testing (e.g. PCR test). In contrast, if \(q=0\), no infected agents are tested. We consider both \({\mathrm{R}}_{\mathrm{N}}\) and \({\mathrm{R}}_{\mathrm{Q}}\) have no infectivity. When the agent Q stays in hospital, \({\beta }_{\mathrm{Q}}\) takes a negligible value. However, when Q is waiting (or staying) at home, it is not negligible. In the present article, we assume \({\beta }_{\mathrm{N}}>{\beta }_{\mathrm{Q}}\) as discussed later.

Simulations are carried out either by local or global interaction. Initially, few infected individuals are randomly positioned, and we put empty cells with density \({\rho }_{0}\); in this article we put \({\rho }_{0}=0.2\). Simulation for local interaction is performed as follows.

-

(i)

Infection processes (2a) and (2b): we randomly choose a single cell. If the cell is S and its nearest-neighbor site is occupied by N or Q, then S change to infected agent \(i\) with probability \({\beta }_{i}\). We put \(i\)=Q by probability \(q\), but \(i\)=N by probability \((1-q)\). Here, boundaries are periodic.

-

(ii)

Recovery and death processes (2c) and (2d): we randomly select one cell. If the site is N, it changes to \({\mathrm{R}}_{\mathrm{N}}\) with rate \({\gamma }_{\mathrm{N}}\). Similarly, if the selected site is Q, it becomes \({\mathrm{R}}_{\mathrm{Q}}\) with rate \({\gamma }_{\mathrm{Q}}\).

-

(iii)

Random walk: we randomly select two neighboring cells. If the first and second chosen cells are respectively the cell of agent \(j\) and empty cell (\(j=\mathrm{S},\mathrm{N},\mathrm{Q},{\mathrm{R}}_{\mathrm{N}},{\mathrm{R}}_{\mathrm{Q}}\)), then both cells are exchanged with migration rate \({m}_{j}\). Hence, the agent \(j\) moves into the empty cell with rate \({m}_{j}\). Note that we have \({m}_{j}=2\), when only step (iii) is repeated twice.

In the simulation, the unit of time \(t\) is measured by Monte Carlo step (MCS)14,15. Namely \(t\) increases by 1 MCS, when steps (i)–(iii) are repeated by 104 times; note 104 is the total cell number of lattice. The simulation is continued until the system reaches a steady state. In the case of global interaction, infection process (i) occurs between any pair of cells. We can skip the random walk in the simulation of global interaction, because all agents randomly distribute.

The well-mixed population for epidemic model is given by mean-field theory (MFT):

Here the densities of S, N, Q, \({\mathrm{R}}_{\mathrm{N}}\) and \({\mathrm{R}}_{\mathrm{Q}}\) are shown in their italics. The total densities of agents are given by \((1-{\rho }_{0})\), where \({\rho }_{0}\) is the density of empty cell. If \(q=0\) and \({\beta }_{\mathrm{Q}}=0\), then Eqs. (3a–3e) agrees with those for SIR model. The threshold phenomenon is well known for SIR model34,38. When \({\beta }_{N}/{\gamma }_{N}\) > 1/S(0), the disease spreads. Similarly, if \(q=1\) and \({\beta }_{\mathrm{N}}=0\), the disease spreads for \({\beta }_{\mathrm{Q}}/{\gamma }_{\mathrm{Q}}\) > 1/S(0).

Results

Results for global interaction

The simulation results of global interaction agree with those predicted by MFT. This is because the global interaction corresponds to the assumption of well-mixed population. First, the numerical calculation for global interaction is reported. In Fig. 1b, a typical population dynamics for MFT are displayed. Model parameters used in all figures are listed in Table S1 (see Supplementary file). At the final equilibrium (\(t\to \infty\)), both densities N \((\infty )\) and Q \((\infty )\) become zero, but \({R}_{N}(\infty )\) and \({R}_{Q}(\infty )\) take constant values. Namely, agents N and Q always change to \({\mathrm{R}}_{\mathrm{N}}\) and \({\mathrm{R}}_{\mathrm{Q}}\), respectively. Hereafter, we will call \({R}_{N}\left(\infty \right)+{R}_{Q}\left(\infty \right)\) "total infection" and \({R}_{Q}(\infty )\) "apparent infection". The former accurately indicates the degree of infection, but its measurement may be impossible. Realistically, only the latter index is announced in public.

In Fig. 2, both total and apparent infections are depicted against the ratio \(q\). We find a threshold phenomenon as observed for SIR model34,38. When the ratio \({\beta }_{N}/{\gamma }_{N}\) takes a small value, the disease never spreads. In contrast, when \({\beta }_{\mathrm{N}}/{\gamma }_{\mathrm{N}}\) takes a large value, the infection can spread. The threshold of \({\beta }_{N}/{\gamma }_{N}\) becomes small, when \({\beta }_{\mathrm{Q}}/{\gamma }_{\mathrm{Q}}\) takes a large value. We also find that the apparent infection (\({R}_{Q}\)) takes a maximum value at \(q={q}_{MAX}\), where \({0<q}_{MAX}<1\). When \({q<q}_{MAX}\), the total number of Q increases with increasing q. On the contrary, when \({q>q}_{MAX}\), it decreases in spite of the increase of q. The value of \({q}_{MAX}\) is found to be increased with the increase of \({\beta }_{N}/{\gamma }_{N}\). It should be emphasized that the total infection monotonically decreases with increasing q. Hence, isolating the infected agents is effective to suppress the infection. In this paper, we put \({\gamma }_{N}{=\gamma }_{\mathrm{Q}}\); this is because both ratios \({\beta }_{N}/{\gamma }_{N}\) and \({\beta }_{\mathrm{Q}}/{\gamma }_{\mathrm{Q}}\) are found to be more important parameters than \({\gamma }_{N}\) and \({\gamma }_{\mathrm{Q}}\). Numerical calculation reveals that both total and apparent infections increase with the increase of either \({\beta }_{N}/{\gamma }_{N}\) or \({\beta }_{\mathrm{Q}}/{\gamma }_{\mathrm{Q}}\).

Results of final densities for MFT. The total infection [\({R}_{N}\left(\infty \right)+{R}_{Q}\left(\infty \right)\)] and apparent infection [\({R}_{Q}\left(\infty \right)\)] are plotted against quarantine ratio (q). We fix \({\gamma }_{\mathrm{N}}={\gamma }_{\mathrm{Q}}=0.2\), \({\beta }_{\mathrm{Q}}=0.1\). (a) \({\beta }_{\mathrm{N}}=0.8\), (b) \({\beta }_{\mathrm{N}}=0.4\) and (c) \({\beta }_{\mathrm{N}}=0.1\).

Results for random-walk simulation

Simulation results for local interaction are described. To know the relation between local and global simulations, we first assume the special case that the migration rate (\({m}_{j})\) of agent \(j\) takes the same value for all agents (\({m}_{j}=m\) for \(j=\mathrm{S},\mathrm{N},\mathrm{Q},{\mathrm{R}}_{\mathrm{N}},{\mathrm{R}}_{\mathrm{Q}}\)). In Fig. 3, the effect of random walk is illustrated; in (a) and (b), the final densities are plotted against the migration rate (\(m\)). It is found that both total and apparent infections increase with \(m\). The infection hardly spreads for \(m=0\), while it widely spreads for a large value of \(m\). Especially when \(m\) is sufficiently large, the results of local interaction approach those predicted by MFT.

Results of random-walk simulation at the final stage (\(t=1000\)). All people (agents) randomly migrate with the same migration rate (m) on a lattice (\(100\times 100\)). In (a) and (b), the total infection [\({R}_{N}\left(\infty \right)+{R}_{Q}\left(\infty \right)\)] and apparent infection [\({R}_{Q}\left(\infty \right)\)] are plotted against m, respectively. The straight lines indicate the results of MFT which agree with those of global interaction.

Realistically, both agents Q and \({\mathrm{R}}_{\mathrm{Q}}\) never move. Next, we consider the case that three agents (S, N, \({\mathrm{R}}_{\mathrm{N}}\)) can move; we fix \({m}_{\mathrm{S}}=2\), and change the migration rates of N and \({\mathrm{R}}_{\mathrm{N}}\) with the same rate (\({m}_{k}={m}_{\mathrm{N}}\) for \(k=\) \({\mathrm{R}}_{\mathrm{N}}\)). In Fig. 4, the final densities are plotted against \({m}_{\mathrm{N}}\), where (a) \(\left(q,{\beta }_{N},{\beta }_{Q}\right)=\left(0.2, 0.3, 0.1\right)\), (b) \((q,{\beta }_{N},{\beta }_{Q})=(0.2, 0.1, 0.3)\) and (c) \((q,{\beta }_{N},{\beta }_{Q})=(0.8, 0.3, 0.1)\). Both values \(q=0.2\) and \(q=0.8\) represent the cases that the inspection is insufficient and sufficient, respectively. Figure 4b represents a symmetrical case to Fig. 4a: \({\beta }_{N}<{\beta }_{Q}\). It is found from Fig. 4a that both total infection (\({R}_{N}+{R}_{Q}\)) and apparent infection (\({R}_{Q}\)) rapidly increase with the increase of \({m}_{\mathrm{N}}\). When N and \({\mathrm{R}}_{\mathrm{N}}\) sufficiently move around, the simulation results of random walk agree with those predicted by MFT (well-mixed population). The infection rapidly spreads. In contrast, Fig. 4b shows different behavior. For small values of \({\beta }_{\mathrm{N}}\), both total and apparent infections hardly increase in spite of the increase of \({m}_{\mathrm{N}}\); the infection becomes very difficult to spread. Similarly, when the inspection is sufficient (\(q=0.8\)), the infection can be suppressed.

Serious effect of non-quarantined agents (N). Both [\({R}_{N}\left(\infty \right)+{R}_{Q}\left(\infty \right)\)] and \({R}_{Q}\left(\infty \right)\) are plotted against \({m}_{\mathrm{N}}\). Uninfected agent (S) can move with \({m}_{\mathrm{S}}=2\). The horizontal axis means the migration rate (\({m}_{\mathrm{N}})\) of N, where both N and \({\mathrm{R}}_{\mathrm{N}}\) move with the same rate. In contrast, the other agents (Q and \({\mathrm{R}}_{\mathrm{Q}}\)) never move: \({m}_{k}=0\) for \(k=\mathrm{Q},{\mathrm{R}}_{\mathrm{Q}}\).

In Fig. 5a and b, the total (\({R}_{N}+{R}_{Q}\)) and apparent (\({R}_{Q}\)) infections are plotted against q, respectively. Here, three agents (\(\mathrm{S},\mathrm{N},{\mathrm{R}}_{\mathrm{N}}\)) can move: \({m}_{j}=10\) for \(j=\mathrm{S},\mathrm{N},{\mathrm{R}}_{\mathrm{N}}\) but \({m}_{k}=0\) for \(k=\mathrm{Q},{\mathrm{R}}_{\mathrm{Q}}\). As predicted by MFT, the total infection monotonically decreases with the increase of q, but the apparent infection has the maximum at \(q={q}_{MAX}\). The value of \({q}_{MAX}\) for local interaction is found to be smaller, compared to the prediction of MFT. In Fig. 5c and d, both total and apparent infections are also plotted against \({\beta }_{\mathrm{N}}\), respectively. These figures display the phase transition. When \({\beta }_{\mathrm{N}}\) takes a small value, the infection never spreads. With the increase of \({\beta }_{\mathrm{N}}\), the infected people suddenly increase. In Fig. 6, typical spatial distributions are displayed, where no agent moves in (a), only S moves in (b), and three agents (S, \(\mathrm{N}, {\mathrm{R}}_{\mathrm{N}}\)) move in (c). For the sake of comparison, the result of global simulation (random distribution) is displayed in Fig. 6d. In the cases of Fig. 6a and b, the infection is suppressed; many cells are occupied by blue (S). The infected agents form clusters and stay inside localized spots. However, in Fig. 6c and d, the infection widely spread. It is therefore important to stop the movement of N agents.

Comparison between local and global interactions. In the former, random-walk simulations are carried out; three agents (S, \(\mathrm{N}, {\mathrm{R}}_{\mathrm{N}}\)) can move with the same rate \({m}_{j}=10\) for \(j=\mathrm{S}, \mathrm{N}, {\mathrm{R}}_{\mathrm{N}}\) (\({m}_{k}=0\) for \(k=\mathrm{Q},{\mathrm{R}}_{\mathrm{Q}}\)). In (a) and (b), both [\({R}_{N}\left(\infty \right)+{R}_{Q}\left(\infty \right)\)] and \({R}_{Q}\left(\infty \right)\) are plotted against the quarantine ratio (q), respectively. In (c) and (d), the same as (a) and (b) are plotted, but the horizontal axis denotes the infection rate (\({\beta }_{\mathrm{N}}\)) of N.

Typical spatial patterns at the final stage (\(t=1500\)). (a) Interactions occur between adjacent cells (local interaction). Nobody can move around ("lockdown"). (b) Local interaction. Only agent S can move around (\({m}_{\mathrm{S}}=10\), but \({m}_{j}=0\) for \(j\ne \mathrm{S}\)). (c)Local interaction. Mobile agents are limited to S, N and \({\mathrm{R}}_{\mathrm{N}}\); namely \({m}_{j}=10\) for \(j=\mathrm{S},\mathrm{N},{\mathrm{R}}_{\mathrm{N}}\) but \({m}_{k}=0\) for \(k=\mathrm{Q},{\mathrm{R}}_{\mathrm{Q}}\)). (d) Global interaction (random distribution). Each site is either empty (white) or occupied by S (blue), RN (green) or RQ (black).

Discussion

The coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 has distinct features never seen for previous coronaviruses, such as SARS and MERS. In the case of SARS-CoV-2, many infected people have mild or asymptomatic symptoms, but they may have considerably high infectivity27,30,31,32,33. We demonstrate the serious role of infected people who are not quarantined (N). To this end, we have modified SIR model; infected individual (I) is divided into two groups (N and Q). Similarly, recovered individual (R) is divided into \({\mathrm{R}}_{\mathrm{N}}\) and \({\mathrm{R}}_{\mathrm{Q}}\) to distinguish the total and apparent infections. Model (2) resembles SIQR model24,43,44. In the latter case, infected agent (I) always transitions to Q with a constant probability (per unit time). For this reason, N cannot be defined well. However, in model (2), we assume the transition occurs only in the early stages of infection. Those who did not transition to Q are defined by N agents; in simple terms, a person who is infected but not tested is an agent N.

The setting of parameter values is discussed. If the value of \({\beta }_{N}/{\gamma }_{N}\) or \({\beta }_{Q}/{\gamma }_{Q}\) is sufficiently high, then the infection easily spreads. In the present paper, the parameters are set based on the following facts: (i) COVID-19 has been suppressed due to lockdown and other regulation of people’s behavior. (ii) Once unlocked, the infection spreads again (e.g. USA and Australia)4. In our model, the disease disappears when all people stop moving, but the infection spreads when people move frequently (see Fig. 3). Moreover, we assume \({\beta }_{\mathrm{N}}>{\beta }_{\mathrm{Q}}\) for the following reasons. Asymptomatic or mildly infected individuals tend to become agent N. On the other hand, those with severe disease may become agent Q. Since agent Q is quarantined, its infectivity (\({\beta }_{\mathrm{Q}}\)) may be low. In contrast, the infectivity (\({\beta }_{\mathrm{N}}\)) of N may be higher than \({\beta }_{\mathrm{Q}}\). This is because the agent N looks like uninfected agent (S); nevertheless, the value of \({\beta }_{N}/{\gamma }_{N}\) may considerably high27,30,31,32,33. Provided that \({\beta }_{\mathrm{N}}\) takes a small value, the infection hardly spreads as shown in Fig. 4b.

Random-walk simulation reveals that both total [\({R}_{N}\left(\infty \right)+{R}_{Q}\left(\infty \right)\)] and apparent [\({R}_{Q}(\infty )\)] infections rapidly increase with increasing the mobility (\({m}_{N}\)) of N (see Fig. 4). However, when the value of \({\beta }_{N}/{\gamma }_{N}\) is low, or when \(q\) takes a high value, the infection hardly spreads. Such a low value of \({\beta }_{N}/{\gamma }_{N}\) means the weak infectivity of N, and the high value of \(q\) denotes the small population size of N. Hence, non-quarantined infected individuals (N) play serious roles for epidemic spreading. It should be noted that the movement of \({\mathrm{R}}_{\mathrm{N}}\) never makes a large difference: if \({\mathrm{R}}_{\mathrm{N}}\) stops to move, Figs. 4, 5, and 6 are almost unchanged. Only when the movement of N is suppressed, the infection can be suppressed.

We discuss spatial pattern formations (see Fig. 6). As illustrated in Fig. 6a, the infection hardly spreads, because all people never move ("lockdown"). Most cells are blue (agent S). The infected agents (green and black) stay inside localized spots. Such a cluster formation may be a merit of lockdown: it is advantageous in taking measures against infectious diseases. Similarly, even when only agent S (non-infected person: blue cell) moves, the infection can be suppressed (see Fig. 6b). The following question arises: Why the infection is suppressed, despite the large number of non-infected persons intensely move. We consider this suppression comes from the spatial pattern formation. Both Fig. 6a and b have the similar distributions: the infected people form clusters. Since infected agents aggregate, the contact between infected and non-infected individuals is effectively decreased.

Conclusion

In the present article, we demonstrate the serious role of infected people who are not quarantined (N). Both mean-field theory and Monte Carlo simulation reveal the result schematically shown in Fig. S1 (see Supplementary file). The total infection monotonically decreases with the increase of quarantine ratio (q). In contrast, the apparent infection has the maximum at \({q=q}_{\mathrm{MAX}}\). For \({q>q}_{\mathrm{MAX}}\), the density of infected people decreases in spite of increasing q. Hence, it is important to promote the inspections; e.g. PCR test. Random-walk simulation reveals that the infection rapidly spreads with increasing the mobility of N. If the movement of N is suppressed, the infection can be suppressed. This conclusion is also confirmed by spatial distribution. Figure 6a indicates the spatial pattern of "lockdown"; infected people form clusters, because all people cannot move. Similar distribution is observed, if infected agents never move (see Fig. 6b). Since infected people aggregate, the infection hardly spreads. Hence, suppressing the movement of infected people (or expanding the tests) is as effective as lockdown. This result for COVID-19 should be unique property never seen for both SARS and MERS. It is therefore important to detect and quarantine the asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infected persons27,30,31,32,33.

References

Wu, Z. & McGoogan, J. M. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: Summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese center for disease control and prevention. JAMA 323, 1239–1242. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.2648 (2020).

Koo, J. R. et al. Interventions to mitigate early spread of SARS-CoV-2 in Singapore: A modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis. 20, 678–688. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30162-6 (2020).

Zou, L. et al. SARS-CoV-2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 1177–1179. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc2001737 (2020).

World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. https://covid19.who.int. Accessed 1 Nov 2021.

National Institutes of Health. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Treatment Guidelines. https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/ (2021).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 Vaccine Effectiveness Research. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/effectiveness-research/protocols.html. Accessed 1 Nov 2021.

Atalan, A. Is the lockdown important to prevent the COVID-19 pandemic? Effects on psychology, environment and economy-perspective. Ann. Med. Surg. 56, 38–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amsu.2020.06.010 (2020).

Saglietto, A., D’Ascenzo, F., Zoccai, G. B. & Ferrari, G. M. D. COVID-19 in Europe: The Italian lesson. Lancet 395, 1110–1111. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30690-5 (2020).

Dagan, N. et al. BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine in a nationwide mass vaccination setting. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 1412–1423. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2101765 (2021).

Mikler, A. R., Venkatachalam, S. & Abbas, K. Modeling infectious diseases using global stochastic cellular automata. J. Biol. Syst. 13, 421–439. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218339005001604 (2005).

White, S. H., Rey, A. M. & Sánchez, G. R. Modeling epidemics using cellular automata. Appl. Math. Comput. 186, 193–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amc.2006.06.126 (2007).

Gupta, A. K. & Redhu, P. Analyses of driver’s anticipation effect in sensing relative flux in a new lattice model for two-lane traffic system. Physica A 392, 5622–5632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physa.2013.07.040 (2013).

Szolnoki, A. & Perc, M. Competition of tolerant strategies in the spatial public goods game. New J. Phys. 18, 083021. https://doi.org/10.1088/1367-2630/18/8/083021 (2016).

Szolnoki, A. & Perc, M. Second-order free-riding on antisocial punishment restores the effectiveness of prosocial punishment. Phys. Rev. X 7, 041027. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevX.7.041027 (2017).

Nakagiri, N., Tainaka, K. & Yoshimura, J. Bond and site percolation and habitat destruction in model ecosystems. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 74, 3163–3166. https://doi.org/10.1143/JPSJ.74.3163 (2005).

Szabó, G. & Fath, G. Evolutionary games on graphs. Phys. Rep. 446, 97–216. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2007.04.004 (2007).

Yokoi, H., Tainaka, K., Nakagiri, N. & Sato, K. Self-organized habitat segregation in an ambush-predator system: Nonlinear migration of prey between two patches with finite capacities. Ecol. Inform. 55, 101022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoinf.2019.101022 (2020).

Guo, H., Yin, Q., Xia, C. & Dehmer, M. Impact of information diffusion on epidemic spreading in partially mapping two-layered time-varying networks. Nonlinear Dyn. 105, 3819–3833 (2021).

Morita, S. Type reproduction number for epidemic models on heterogeneous networks. Physica A 587, 126514 (2022).

Ito, H., Yamamoto, T. & Morita, S. The type-reproduction number of sexually transmitted infections through heterosexual and vertical transmission. Sci. Rep. 9, 17408. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-53841-8 (2019).

Tomé, T. & Ziff, R. M. Critical behavior of the susceptible-infected-recovered model on a square lattice. Phys. Rev. E 82, 051921. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevE.82.051921 (2010).

Nagatani, T., Ichinose, G. & Tainaka, K. Epidemic spreading of random walkers in metapopulation model on an alternating graph. Physica A 520, 350–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physa.2019.01.033 (2019).

Pastor-Satorras, R. & Vespignani, R. Epidemic spreading in scale-free networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 3200. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevLett.86.3200 (2001).

Nagatani, T. & Tainaka, K. Diffusively coupled SIQRS epidemic spreading in hierarchical small-world network. J. Phys. Soc. Japan 90, 013001. https://doi.org/10.7566/JPSJ.90.013001 (2021).

Xia, Y., Bjornstad, O. N. & Grenfell, B. T. Measles metapopulation dynamics: A gravity model for epidemiological coupling and dynamics. Am. Nat. 164, 267–281. https://doi.org/10.1086/422341 (2004).

Chen, N. et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: A descriptive study. Lancet 395, 507–513. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7 (2020).

Nogrady, B. What the data say about asymptomatic COVID infections. Nature 587, 534–535. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-03141-3 (2020).

Japanese Association for Infectious Diseases and Japanese Society for Infection Prevention and Control. Clinical Response to New Coronavirus Infection: To Avoid Confusion in the Medical Sites and Save the Lives of Serious Cases (2020/04/02), in Japanese. https://www.kansensho.or.jp/uploads/files/topics/2019ncov/covid19_rinsho_200402.pdf. Accessed 1 Nov 2021.

He, X. et al. Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19. Nat. Med. 26, 672–675. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-020-0869-5 (2020).

Hasanoglu, I. et al. Higher viral loads in asymptomatic COVID-19 patients might be the invisible part of the iceberg. Infection 49, 117–126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s15010-020-01548-8 (2021).

Subramanian, R., He, Q. & Pascual, M. Quantifying asymptomatic infection and transmission of COVID-19 in New York City using observed cases, serology, and testing capacity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 118, e2019716118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2019716118 (2021).

Oran, D. P. & Topol, E. J. Prevalence of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. Ann. Intern. Med. 173, 362–367. https://doi.org/10.7326/M20-3012 (2020).

Zhang, J., Wu, S. & Xu, L. Asymptomatic carriers of COVID-19 as a concern for disease prevention and control: more testing, more follow-up. Biosci. Trends 14, 206–208. https://doi.org/10.5582/bst.2020.03069 (2020).

Anderson, R. M. & May, R. M. Infectious Diseases of Humans: Dynamics and Control (Oxford University Press, 1992).

Sharma, N. & Gupta, A. K. Impact of time delay on the dynamics of SEIR epidemic model using cellular automata. Physica A 471, 114–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physa.2016.12.010 (2017).

Maier, B. F. & Brockmann, D. Effective containment explains subexponential growth in recent confirmed COVID-19 cases in China. Science 368, 742–746. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abb4557 (2020).

Dickman, R. A SEIR-like model with a time-dependent contagion factor describes the dynamics of the Covid-19 pandemic. MedRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.06.20169557 (2020).

Kermack, W. O. & McKendrick, A. G. A contribution to the mathematical theory of epidemics. Proc. R. Soc. A 115, 700–721. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspa.1927.0118 (1927).

Sazonov, I., Kelbert, M. & Gravenor, M. B. Travelling waves in a network of SIR epidemic nodes with an approximation of weak coupling. Math. Med. Biol. 28, 165–183. https://doi.org/10.1093/imammb/dqq016 (2011).

Boccara, N. & Cheong, K. Automata network SIR models for the spread of infectious diseases in populations of moving individuals. J. Phys. A 25, 2447. https://doi.org/10.1088/0305-4470/25/9/018 (1992).

Kato, F. et al. Combined effects of prevention and quarantine on a breakout in SIR model. Sci. Rep. 1, 10. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep00010 (2011).

Liccardo, A. & Fierro, A. A lattice model for influenza spreading. PLoS ONE 8, e63935. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0063935 (2013).

Chowell, G., Nishiura, H. & Bettencourt, L. M. A. Comparative estimation of the reproduction number for pandemic influenza from daily case notification data. J. R. Soc. Interface 4, 155–166. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsif.2006.0161 (2007).

Liu, Y. & Zhao, Y. Y. The spread behavior analysis of a SIQR epidemic model under the small world network environment. J. Phys. Conf. Series 1267, 012042. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1267/1/012042 (2019).

Morita, S. Six susceptible-infected-susceptible models on scale-free networks. Sci. Rep. 6, 22506. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep22506 (2016).

Reppas, A., Spiliotis, K. & Siettos, C. I. On the effect of the path length of small-world networks on epidemic dynamics. Virulence 3, 146–153. https://doi.org/10.4161/viru.19131 (2012).

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to H. Yokoi for assistance with the numerical simulations. This work was supported by COVID-19 research project in University of Hyogo and by grants-in-aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports Science and Technology of Japan (Grant Number 18K11466). No additional external funding received for this study. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. The authors were solely responsible for the design, conduct, and interpretation of all studies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.N., K.T. and K.S. developed the models. N.N. carried out computer simulations. K.S. performed mathematical analysis and numerical calculations. K.T., N.N. and K.S. wrote the draft paper. Y.S. revised the paper from an epidemiological point of view. All authors discussed the simulation results and contributed to writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Nakagiri, N., Sato, K., Sakisaka, Y. et al. Serious role of non-quarantined COVID-19 patients for random walk simulations. Sci Rep 12, 738 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-04629-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-04629-2

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.