Abstract

Ginkgo biloba L. is an ancient relict plant with rich pharmacological activity and nutritional value, and its main physiologically active components are flavonoids and terpene lactones. The bZIP gene family is one of the largest gene families in plants and regulates many processes including pathogen defense, secondary metabolism, stress response, seed maturation, and flower development. In this study, genome-wide distribution of the bZIP transcription factors was screened from G. biloba database in silico analysis. A total of 40 bZIP genes were identified in G. biloba and were divided into 10 subclasses. GbbZIP members in the same group share a similar gene structure, number of introns and exons, and motif distribution. Analysis of tissue expression pattern based on transcriptome indicated that GbbZIP08 and GbbZIP15 were most highly expressed in mature leaf. And the expression level of GbbZIP13 was high in all eight tissues. Correlation analysis and phylogenetic tree analysis suggested that GbbZIP08 and GbbZIP15 might be involved in the flavonoid biosynthesis. The transcriptional levels of 20 GbbZIP genes after SA, MeJA, and low temperature treatment were analyzed by qRT-PCR. The expression level of GbbZIP08 was significantly upregulated under 4°C. Protein–protein interaction network analysis indicated that GbbZIP09 might participate in seed germination by interacting with GbbZIP32. Based on transcriptome and degradome data, we found that 32 out of 117 miRNAs were annotated to 17 miRNA families. The results of this study may provide a theoretical foundation for the functional validation of GbbZIP genes in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ginkgo biloba, known as a “living fossil,” began to appear 280 million years ago and is widely distributed throughout the world1. G. biloba extract (EGb 761) is the initial drug of choice for Alzheimer’s treatment2. EGb is widely used in the treatment of hypertension, cardiovascular and neurological diseases3,4,5. The main physiologically active components of G. biloba extract are flavonoids and terpene lactones6,7. Flavonoids have free radical scavenging activity8. There are not less than 6% terpene trilactones and 24% flavonoids in EGb9. The demand for EGb in the market is increasing due to its important medicinal value. However, the content of flavonoid in G. biloba is extremely low which is a serious obstacle in the application of EGb. It has been reported that genetic engineering techniques is an effective way to enhance the content of secondary metabolites such as flavonoids10.

When plants are subjected to low temperature, drought, salt stress, or exogenous hormones, transcription factors are induced to bind to the corresponding cis-acting elements, activating the expression of downstream genes to improve plant tolerance11. bZIP, one of the largest families in transcription factor, plays an important role in physiological processes such as biotic and abiotic stress responses and development in plants12. All bZIP genes share a conserved bZIP domain, which contains two structural features (a DNA-binding basic region and a dimerizing leucine zipper region). The N-terminus contains a basic region of about 16 amino acid residues, including a nuclear localization signal, immediately followed by the N-X7-R/K conserved base sequence. The C terminus consists of a heptad repeat of leucine or other bulky hydrophobic amino acids13,14. To bind DNA, two subunits adhere via interaction between the hydrophobic sides of their helices, which creates a superimposing coiled-coil structure15. ACGT is the core sequence recognized by bZIP TF, and the corresponding cis-acting elements are A-box, G-box, and C-box14,16.

Flavonoid biosynthesis involved in multiple enzymes in plants, and its accumulation is not determined by a single key enzyme. Besides, the process is also regulated by many transcription factors. A bZIP transcription factor was found to be involved in the metabolism of flavonoids. HY5 belongs to the H subclass of the bZIP gene family, which was proved to be involved in plant photomorphogenesis17,18. Subsequently, it was shown that HY5 was also involved in the anthocyanin metabolism process, which belongs to flavonoids19. Qiu et al. obtained SlHY5 frameshift mutated and found that the anthocyanin content in the mutant was lower than that in wild-type tomato20. HY5 can improve plant cold tolerance through direct regulation of CBF or indirect regulation of MYB1521.Anthocyanins accumulation could be inhibited by Gibberellins at low temperature in plants, while the expression level of the gibberellin signaling pathway gene GA2ox1 showed HY5-dependent22. In strawberry, HY5-bHLH9 heterodimer formed to regulate light-dependent coloration and anthocyanin biosynthesis, suggesting that HY5 can be involved in plant anthocyanin metabolism by acting together with other genes23. Nguyen et al.24 found HY5 binds directly to the MYBD promoter in this process to promote anthocyanin accumulation. Zhang et al.25 found that HY5 or HYH TFs promote anthocyanin accumulation by upregulating DFR, a key gene downstream of the anthocyanin biosynthesis pathway in A. thaliana. The bZIP TF was shown to affect the biosynthesis of anthocyanins in red raspberries26. Furthermore, the bZIP TF HY5 in regulates anthocyanin synthesis through the activation of AtMYB75 transcription in A. thaliana27. Droge et al.28 isolated the G/HBF-1 (bZIP) TF from soybean and found that G/HBF-1 can bind to the H-box and G-box in the promoter region of the CHS gene to activate CHS gene expression and substantially increase phytoalexin level, thereby improving disease resistance in soybean. Akagi et al.29 found that DkbZIP5 was involved in proanthocyanidin biosynthesis by binding to the ABRE element of the promoter region of DkMYB4 in persimmon callus. Fan et al.15 identified a total of 135 RsbZIP genes from radish genome and found that RsbZIP011 and RsbZIP102 were potential participants in the radish anthocyanin synthesis pathway. Therefore, regulating the expression of TFs is another effective way to increase flavonoid content.

The whole genome sequence of G. biloba has been published in 2016. The bZIP gene family is important in plant development and stress response. However, the bZIP transcription factors have not been reported in G. biloba yet. In the present study, the whole genome sequence of G. biloba was used to screen for the GbbZIP gene family. We analyzed the physicochemical property, phylogenetic relationship, chromosome localization, gene structure, motifs, tissue expression pattern, protein-protein interaction network, miRNAs of GbbZIP gene family and their expressional patterns under SA, MeJA, and low temperature treatment. The result will provide a theoretical basis for subsequent studies on the mechanism of action and function of the bZIP gene family in G. biloba.

Results

Identification of bZIP genes in G. biloba

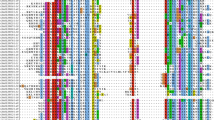

A total of 65 protein sequences were identified from the G. biloba genome using HMMER 3.0 software. 15 bZIP proteins were found to contain no bZIP domains or incomplete bZIP domains by further CDD and Pfam analysis, so they were subsequently removed. The remained 40 proteins containing bZIP domains were named GbbZIP01–GbbZIP40. The proteins encoded by the 40 GbbZIP genes ranged from 66 (GbbZIP34) to 681 (GbbZIP22) amino acids and from 7.90 kDa to 74.44 kDa in relative molecular weight. The isoelectric point was predicted to range from 5.16 to 9.75. As can be seen in Table 1, the GRAVY scores of 40 GbbZIP proteins were negative, indicating they are hydrophilic. 38 GbbZIPs are expressed in cell nucleus. GbbZIP12 and GbbZIP27 are located in the chloroplast and plastid, respectively. Multiple sequence alignment of the conserved domain sequences of 40 GbbZIP members showed that the basic region is composed of N-(X)7-R/K, and the zipper domain is composed of the heptapeptide repeat of leucine (L) or related hydrophobic amino acids (Fig. 1).

Visualization of GbbZIP family conserved domains in G. biloba. Alignment of GbbZIP conserved domains created using WebLogo program (http://weblogo.threeplusone.com/create.cgi). The total height of the letter piles at each position indicates the conservation of the sequence at that position (measured in bits). The height of a single letter in the letter piles represents the relative frequency of the corresponding amino acid at that position.

Chromosomal localization and phylogenetic analysis

Based on genome annotation data, the chromosomal distribution of GbbZIP genes was visualized using TBtools v1.09854 in G. biloba. The bZIP genes are distributed unevenly on 12 chromosomes of G. biloba. A total of 5, 2, 2, 5, 2, 3, 3, 6, 5, 3, 1, and 3 GbbZIPs were distributed on Chr1–Chr12, respectively. Fig. 2 shows that Chr11 contains the fewest GbbZIP genes with only 1, while Chr8 contains the most genes with 6.

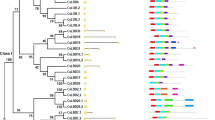

To investigate the phylogenetic relationship among the bZIP family members, a phylogenetic tree was generated including 69 AtbZIPs in A. thaliana and 109 MdbZIPs in Malus domestica. Based on the previous classification of 69 AtbZIPs and 109 MdbZIPs members30, 40 GbbZIPs were divided into 10 subfamilies (Fig. 3): A (6), B (0), C (1), D (3), E (6), F (3), G (5), H (4), I (5), S (5), J (0), K (2), and M (0). In G. biloba, group B, J, and M don't contain GbbZIP members. Group A and E are the largest subfamilies while group S is the largest in A. thaliana and M. domestica.

Phylogenetic tree based on G. biloba, A. thaliana and M. domestica bZIP proteins. MUSCLE in MEGA 6.0 was used for multiple sequence alignments of bZIP conserved domain sequences31,32. The neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree was constructed using MEGA 6.0 with the following parameters: p-distance, pairwise deletion and bootstrap (1000 replicates). The red stars represent GbbZIP members in G. biloba.

Gene structure and motif analysis

To gain insights into the structures of GbbZIP genes, their exon/intron organization was investigated. As shown in Fig. 4b, the number of exons in GbbZIPs ranged from 1 to 12. The gene structure of the same subfamily was relatively conserved. For example, four members in group E contained the same number and length of exons. Out of the six members in group A, five are composed of a long exon, and three short exons. A higher number of exons were found in D and G subclasses, while fewer introns were found in F and S subclasses. The gene structure of subclass A was highly uniform, but the number of introns in subclass H varied considerably.

Characterization of GbbZIP genes in G. biloba. (a) The clustering of GbbZIP proteins based on Neighbor-Joining phylogenetic tree. (b) Exon–intron structures of GbbZIP genes were visualized with GSDS website (http://gsds.gao-lab.org/). The red block represents the coding sequence (CDS), the broken line represents intron. (c) Distribution of conserved motifs for GbbZIP proteins was visualized with TBtools v1.09854.

The motifs of GbbZIPs were analyzed using the MEME website and the results were shown in Fig. 4c. A total of 20 motifs were found in GbbZIPs. Using the PFAM database, motif 1 and motif 9 (Table S2) were identified as the core conserved domains of GbbZIP proteins. Motif 13 and 4 were identified as DOG1 (Delay of Germination 1), which appears to be a highly specific controller seed dormancy33. Motif 12 and 18 were identified as MFMR (Multifunctional mosaic region), and other motifs contained no specific annotation information34. In addition to the core conserved domains, different conserved motifs were also present in different subfamilies. For example, Motif 3, 5, and 7 are only present in subfamily A; motif 4, 11, and 13 are distributed in subfamily D; motif 6, 12, 15, 17, and 18 exist in subfamily G; motifs 8 and motif 10 occur in subfamilies F and E, respectively. Motif 9 was detected only in subclass G and S, suggesting similar functions between the two subclasses that were in the same branch of the evolutionary tree.

Promoter analysis

The sequence 2000 bp upstream of each GbbZIP gene was analysed in PlantCARE website, and the results were visualized with TBtools v1.09854. The detailed cis-acting element information can be found in Table S3. As shown in Fig. 5, the most frequently occurring cis-acting elements contain light-, hormone-, abiotic stress-, and growth- and development- responsive element. G-box, ACE, and GT1 motifs are light-responsive elements, while ABRE, TGA, CGTCA-motif, and TCA-element are ABA-, auxin-, MeJA-, and SA-responsive elements, respectively. Gibberellin responsive element contains GARE-motif and P-box. Among them, the light-responsive element appeared most frequently (158 times) and was the most widely distributed in GbbZIP gene promoters. Nine GbbZIPs contained low-temperature-responsive elements. In addition, other elements include anoxic inducibility (ARE), circadian control, defense and stress (TC-rich), endosperm expression (GCN4-motif), and meristem expression (CAT-box) elements.

Cis-acting elements on the promoters of G. biloba bZIP genes. The 2000 bp upstream sequences of the transcription start site in GbbZIPs were extracted from the G. biloba genome database, and their promoter sequences were submitted to the PlantCARE website (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/).

Analysis of the expression pattern and correlation

The expression pattern of the GbbZIP gene family was analyzed based on FPKM from G. biloba transcription database. As shown in Fig. 6a, 36 GbbZIPs are expressed in eight tissues, except for four genes (GbbZIP09, GbbZIP24, GbbZIP32, and GbbZIP38) that are not expressed in mature leaf and root. GbbZIP13, GbbZIP18, and GbbZIP31 showed high expression characteristics in all eight tissues. GbbZIP38, GbbZIP24, GbbZIP26, and GbbZIP32 showed very low expression levels in all tissues. The expression profiles of GbbZIP11, GbbZIP12, GbbZIP16, and GbbZIP36 were significantly higher in microstrobilus than in other tissues. The expression levels of GbbZIP01, GbbZIP02, GbbZIP21, and GbbZIP25 were lower in mature leaf than in other tissues.

(a) Expression pattern of GbbZIPs in the 8 tissues base on the FPKM in the transcriptome data. (R root, S stem, IL immature leaf, ML mature leaf, M microstrobilus, OS ovulate strobilus, IF immature fruit, MF mature fruit). (b) Correlation analysis (p < 0.05) of the content of flavonoid and the FPKM of GbbZIPs in 8 tissues base on the FPKM in the transcriptome data.

Based on correlation analysis between on the FPKM of GbbZIPs and the flavonoid content in the eight tissues of G. biloba, we obtained two GbbZIPs (GbbZIP08 and GbbZIP15) with correlation coefficients greater than 0.8 (Fig. 6b, Table S4, Table S6, Table S7). These two genes were assigned to subclass H in the evolutionary tree analysis.

GbbZIP protein–protein interaction network prediction

The interaction between GbbZIP proteins was predicted in the website STRING. 33 out of 40 GbbZIP proteins were on the protein-protein interaction network. As shown in Fig. 7, AREB3 (AT3G56850) binds to the embryo specification element and the ABA-responsive element (ABRE) and participates in abscisic acid-regulated gene expression during seed development. ABF2 (AT1G45249) binds to the ABRE motif and involves in drought tolerance. HY5 (AT5G11260) and HYH (AT3G17609) are transcription factors that promote photomorphogenesis in light. Plants inhibit anthocyanin biosynthesis by degrading HY5 at high temperature35.

Protein–protein interaction network for GbbZIPs was analyzed by the STRING website (http://string-db.org/) using the full-length protein sequence16,36. Empty nodes indicate proteins of unknown 3D structure. Filled nodes indicate that some 3D structure is known or predicted.

Prediction and analysis of miRNA regulating GbbZIPs

In order to further understand the GbbZIP genes in G. biloba, we combined transcriptome and degradome sequencing results to screen for 117 miRNA members regulating 33 GbbZIPs. Based on the transcriptome annotation results, a total of 32 miRNAs were matched to 17 miRNA families (Table S5). Fig. 8 showed that 9 out of 40 GbbZIPs were each targeted by only one corresponding miRNA. GbbZIP36, GbbZIP31, GbbZIP11, and GbbZIP32 were targeted by 15, 11, 13, and 9 miRNAs, respectively. Interestingly, some miRNAs targeted more than one GbbZIP gene, such as novel_miR_582 (GbbZIP18 and GbbZIP40), novel_miR_2803 (GbbZIP21 and GbbZIP28), novel_miR_2362 (GbbZIP36 and GbbZIP39), novel_miR_1493 (GbbZIP01 and GbbZIP27), and novel_miR_2752 (GbbZIP03 and GbbZIP10). GbbZIP08 and GbbZIP15 were targeted by novel_miR_850 and novel_miR_715, respectively.

Network diagram of miRNAs targeting GbbZIPs in G. biloba was created using the OmicShare tools (http://www.omicshare.com/tools). Red circle represents GbbZIP members. lilac circle represents miRNAs. The data for the network diagram were obtained from transcriptome and degradome sequencing data.

Differential expression levels of GbbZIPs with hormone treatment

Based on the results of cis-acting element analysis, genes containing a large number of cis-acting elements which are related to SA-, MeJA-, and low temperature-responses were selected for qRT-PCR analysis, and the results were visualized in the form of a heatmap. As shown in the Fig. 9c, most GbbZIPs responded negatively to SA, only the expression levels of GbbZIP08 and GbbZIP33 first increased and then decreased. GbbZIP25, GbbZIP16, GbbZIP11, GbbZIP11, GbbZIP26, GbbZIP10, and GbbZIP29 were downregulated within 24 h after MeJA treatment then increased at 48 h (Fig. 9a). The expression levels of GbbZIP23 and GbbZIP35 peaked at 6 h after MeJA treatment and then started to decrease (Fig. 9a). With low-temperature treatment, the transcription levels of GbbZIP08 and GbbZIP14 were upregulated, while GbbZIP26 increased and then decreased, and reached a peak at 6 h (Fig. 9b).

Heat maps of the relative expression of GbbZIPs under abiotic stress. (a) The relative expression of GbbZIPs under MeJA. (b) The relative expression of GbbZIPs under cold stress. (c) The relative expression of GbbZIPs under SA. Expression values are mapped to a color gradient from low (blue) to high (red) expression.

Discussion

G. biloba is an ancient economic tree species that originated in China and it has a very strong ability to adapt to harsh environments. Therefore, the genetic information of G. biloba is of great research value in plant growth and development, pest and disease defense, abiotic stress, and tree evolution. To date, the bZIP gene family has been identified in A. thaliana (78 bZIPs)30, Populus (86 bZIPs)37, Raphanus sativus (135 bZIPs)15, Solanum tuberosum (80 bZIPs)38, Brassica napus (247 bZIPs)38, and Olea europaea (103 bZIPs)39. However, the bZIP transcription factors in G. biloba have not been reported yet. In this study, a total of 40 GbbZIP members were identified based on the genomic data of G. biloba. Compared to the species above, G. biloba contains the fewest bZIP members with 40 while B. napus contains the most with 247.

We used phylogenetic analysis to classify bZIP genes into 10 groups—40 GbbZIP genes, along with 69 bZIP genes from A. thaliana, and 109 from M. domestica (Fig. 3). The GbbZIP members were not detected in subgroup J, B, and M, which implying that these members were derived gradually during the evolutionary process. In G. biloba, the largest number of GbbZIPs were found in subclasses S, A, and I subgroups. It is similar to A. thaliana30, Populus37, R. sativu15, S. tuberosum40, B. napus38, and O. europaea39 which contains the most bZIP members in S, A, I, and D subclasses. In the Fig. 3, GbbZIP03 was clustered closely with AtbZIP51 (VIP1), which is a putative host factor in Agrobacterium-mediated T-DNA transfer41. Furthermore, GbbZIPs in the same group share a similar gene structure, number of introns and exons, and motif distribution.

HY5 (Elongated Hypocotyl 5) is a major regulator of photomorphogenesis. Studies in apple indicated that MdHY5 promoted anthocyanin accumulation by regulating the expression of MdMYB10 and downstream anthocyanin biosynthesis genes42. SlHY5 in Solanum lycopersicum could directly recognize and bind to the G‐box and ACGT‐containing element in the promoters of anthocyanin biosynthesis genes, such as CHS1, CHS2, and HDR43. It is apparent in the Fig. 6b, the positive correlation between the expression of GbbZIP15 and GbbZIP08 and the content of flavonoids was the highest. In addition, GbbZIP15 and GbbZIP08 was close to AtbZIP56 and MdbZIP67 in the phylogenetic analysis. Blast 2.7.1, a local BLAST program, was used to search for protein sequences similar to GbbZIP08 and GbbZIP15 in the A. thaliana and M. domestica bZIP protein database. AtbZIP56 and MdbZIP67 proteins were found to be the most similar to GbbZIP08 and GbbZIP15 proteins (Table S8, Table S9). AtbZIP56 (HY5) in subclass H has been reported to play an important role in anthocyanin biosynthesis24. MdWRKY11 transcription factor was reported to bind to the W-box in the MdbZIP67 promoter and thus participated in the anthocyanin biosynthesis in M. domestica44. The result implied that GbbZIP15 and GbbZIP08 might be involved in anthocyanin biosynthesis of G. biloba.

SA is a crucial internal signaling molecule needed for the induction of plant defense responses upon attack of a variety of pathogens45. The expression of GbbZIP33 was increased by 20-fold 3 h after SA treatment. However, no significant changes were observed in the expression of GbbZIP33 after MeJA and low-temperature treatment. In Cassava, MebZIP3 was largely increased while MebZIP5 expression was decreased after SA treatment46. The trend of GbbZIP08 was relatively consistent in MeJA and SA treatment. Its expression level first increased, then decreased, and peaked 3 h after treatment. It showed a similar trend with CsBZIP40 in sweet orange. The expression level of CsBZIP40 increased significantly from 12 h and then decreased after 36 h After MeJA treatment47. With low-temperature treatment, GbbZIP08 showed an increasing trend from 0 h to 8 h, and the expression was significantly increased. Similarly, the result was also found in apple. MdbZIP67 (MdHY5) overexpression improved the cold resistance in apple and transgenic A. thaliana48. It indicated that GbbZIP08 might participate in the cold stress in G. biloba. The expression level of GbbZIP29 was upregulated under low-temperature stress while the low-temperature-responsive element (CCGAAA) was found in GbbZIP29 In the promoter analysis.

In the protein-protein interaction analysis, it revealed that 33 out 40 GbbZIP members were on the protein-protein interaction network (Fig. 7). BZIP53 (AT3G62420) and bZIP44 (AT1G75390) both involved in the positive regulation of seed germination through MAN7 gene activation49. Therefore, the interaction between BZIP53 (homology of GbbZIP09) and bZIP44 (homology of GbbZIP32) might participate in seed germination. GbbZIP08 and GbbZIP15 were speculated as homologous genes of HY5 (AtbZIP56). It has been reported that HY5 was involved in modulating seed germination and seedling development in response to abscisic acid and salinity50. HYH (HY5 homology) has a similar functions as HY5 in plant photomorphogenesis and anthocyanin accumulation22,51. It was speculated that GbbZIP34 (homology of HYH) was involved in flavonoid biosynthesis in G. biloba by interacting with GbbZIP08 and GbbZIP15 (homology of HY5).

The reported miRNAs associated with anthocyanin biosynthesis include miR858a, miR828, and miR156. In tomato, miR828 repressed anthocyanin expression by cleaving the structural gene SlMYB7-like52. 32 out of 117 miRNAs were annotated to 17 families (Table S5). In this study, GbbZIP08 and GbbZIP15 were targeted by novel_miR_850 and novel_miR_715, respectively. The miRNAs (novel_miR_1493, novel_miR_30, novel_miR_3054, novel_miR_3292, novel_miR_443, novel_miR_462, and novel_miR_82) were annotated as miR1314 family and they all targeted GbbZIP37. MIR1314 appears gymnosperm-specific and is likely to exist as a luster53. GbbZIP06 was targeted by novel_miR_1493 and novel_miR_18 which were identified as miR397. Overexpression of native Musa-miR397 enhanced plant biomass without compromising abiotic stress tolerance in banana54. The miRNAs (novel_miR_2243, novel_miR_3072, novel_miR_2847, and novel_miR_775) were annotated as miR159 in this study. It was reported that miR159 inhibited the root growth by repressed the expression of MYB33, MYB65 and MYB101 in A. thaliana55.

Conclusions

In the current study, the genome-wide distribution of the GbbZIP gene family was identified in G. biloba. We conducted a preliminary analysis of the physicochemical properties, chromosome localization, evolutionary relationship, tissue-specific expression pattern, protein–protein interaction, and miRNAs. We verified the response of 20 GbbZIPs to MeJA, SA, and low temperature through qRT-PCR. Based on the correlation analysis and the phylogenetic analysis, GbbZIP08 and GbbZIP15 were inferred to be HY5 genes involved in anthocyanin biosynthesis in G. biloba. The results will be important for the further functional characterization of GbbZIP08 and GbbZIP15 in G. biloba.

Methods

Plant materials and treatments

Annual G. biloba seedlings were used in this study. The G. biloba seeds were derived from Ginkgo Resource Garden at the western campus of Yangtze University (E:112.15373°, N:30.357146°) and they were carried out in accordance with relevant institutional, national or international guidelines and regulation. Before sowing, G. biloba seeds were immersed in tap water for 3 days to absorb enough water. Then, they were taken out and covered with wet gauze to be promoted germination. When the radicle of the seeds grew to 1 cm, they were planted in pots (15 cm in height and 17 cm in diameter) and grown in a greenhouse (E:112.152283°, N:30.358268°). We watered the seedlings every 5 days. When the seedlings developed 5–6 leaves after 2 month, the leaves of seedlings were treated with 10 mM salicylic acid (SA), 1 mM methyl jasmonate (MeJA) and 4 °C, respectively56,57. Exogenous hormones were sprayed on the seedling leaves in this study. Leaves treated with water were used as the control. Three replicates were selected for each treatment, and each replicate contained 10 seedlings. After three different treatments, leaves of annual G. biloba seedlings in each treatment were collected at 0, 3, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h, separately58.

Identification of GbbZIP genes

The genome data and annotated files of G. biloba were downloaded from the GIGA Database website (http://gigadb.org/dataset/100613)59,60. The hidden Markov model (PF00170, PF07716, and PF03131) of the bZIP gene was obtained from the Pfam database61. Protein sequences containing the bZIP domain were searched in the G. biloba protein database using HMMER 3.0 software. Subsequently, CDD (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi)62 and SMART (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/)63 searches were used to check the integrity of the bZIP domain. The conserved domain sequence of each GbbZIP member was extracted and used for multiple sequence alignment with MEGA 6.0 software. The alignment file was visualized in the website WebLogo (http://weblogo.threeplusone.com/create.cgi). The physicochemical properties of GbbZIP proteins were predicted using the online website ExPASy64. The website WoLF PSORT (https://wolfpsort.hgc.jp/) was used to predict subcellular localization of GbbZIPs.

Phylogenetic analysis and chromosome localization

All bZIP protein sequences of A. thaliana and M. domestica were downloaded from the TAIR database (https://www.arabidopsis.org/index.jsp)48 and GDR database (https://www.rosaceae.org/)65, respectively. Multiple sequence alignment of bZIP proteins was performed using MUSCLE in MEGA 6.066. The neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree was then constructed using MEGA 6.0 with the following parameters: p-distance, pairwise deletion, and bootstrap (1000 replicates)67. Combining the genome sequence files and annotation files, gene chromosome localization was visualized using the TBtools v1.0985468.

Analysis of gene structure, conserved motif, and promoter

To further analyze the distribution of the GbbZIP genes in G. biloba, GbbZIP protein motifs were predicted on the website MEME (https://meme-suite.org/meme/)4. To acquire the gene structure, the nucleus sequences of GbbZIP genes were submitted to GSDS website (http://gsds.gao-lab.org/)69. The 2000 bp upstream sequences of the transcription start site in GbbZIPs were extracted from the G. biloba genome database, and their promoters were predicted on the PlantCARE website (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/)70.

Expression pattern analysis based on transcriptome and correlation analysis

To investigate the expression pattern of the GbbZIP gene family, we used FPKM of GbbZIP genes in eight tissues (root, stem, immature leaf, mature leaf, microstrobilus, ovulate strobilus, immature fruit, and mature fruit) based on the transcriptome data71. Subsequently, the correlation index between the FPKM of GbbZIP genes and the content of flavonoid in eight tissues was calculated (p < 0.05) by Pearson's correlation method using the OmicShare tools (http://www.omicshare.com/tools).

Protein–protein interaction network

The protein sequences of 40 GbbZIP genes were extracted and sent to the STRING website (http://string-db.org/). The interaction network of GbbZIP proteins was predicted in the STRING website using a model plant A. thaliana16,72. The result was imported into Adobe Illustrator 2020 software for modification.

miRNA target prediction of GbbZIP genes

Based on transcriptome and degradation data, miRNAs targeting the GbbZIP genes were screened from the annotation files6,71. The screening results were visualized using OmicShareTools (http://www.omicshare.com/tools), a free online platform.

qRT-PCR analysis

Total RNA of G. biloba was extracted using the MiniBEST Plant RNA Extraction Kit (TaKaRa, Dalian) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. First-strand cDNA was synthesized using HiScript II 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Vazyme, Nanjing). qRT-PCR was performed according to the procedure of ChamQ Universal SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme, Nanjing). The Integrated DNA Technologies website (https://sg.idtdna.com/pages) was used to design the primers (Table S1). The relative expression level was normalized to the GbGAPDH (GenBank ID: L26924.1) gene and calculated using the 2−∆∆Ct method73.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS software (Version 22). The relative expression level was presented as the mean ± standard error (SE). Duncan’s multiple range tests were conducted to examine signifcant diferences among means at p < 0.05.

References

He, B. et al. Analysis of codon usage patterns in Ginkgo biloba reveals codon usage tendency from A/U-ending to G/C-ending. Sci. Rep. 6, 1–11 (2016).

Zimmermann, M., Colciaghi, F., Cattabeni, F. & Di Luca, M. Ginkgo biloba extract: From molecular mechanisms to the treatment of Alzhelmer’s disease. Cell Mol. Biol. 48, 613–623 (2002).

Singh, S. K., Srivastav, S., Castellani, R. J., Plascencia-Villa, G. & Perry, G. Neuroprotective and antioxidant effect of Ginkgo biloba extract against AD and other neurological disorders. Neurotherapeutics 16, 666–674 (2019).

Tian, J., Liu, Y. & Chen, K. Ginkgo biloba extract in vascular protection: Molecular mechanisms and clinical applications. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 15, 532–548 (2017).

Xiong, X. J. et al. Ginkgo biloba extract for essential hypertension: A systemic review. Phytomedicine 21, 1131–1136 (2014).

Ye, J. et al. Comparative transcriptome analysis reveals the potential stimulatory mechanism of terpene trilactone biosynthesis by exogenous salicylic acid in Ginkgo biloba. Ind. Crop Prod. 145, 112104 (2020).

Ye, J. et al. Global identification of Ginkgo biloba microRNAs and insight into their role in metabolism regulatory network of terpene trilactones by high-throughput sequencing and degradome analysis. Ind. Crop Prod. 148, 112289 (2020).

Liu, X.-G., Wu, S.-Q., Li, P. & Yang, H. Advancement in the chemical analysis and quality control of flavonoid in Ginkgo biloba. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 113, 212–225 (2015).

van Beek, T. A. & Montoro, P. Chemical analysis and quality control of Ginkgo biloba leaves, extracts, and phytopharmaceuticals. J. Chromatogr. A 1216, 2002–2032 (2009).

Fernie, A. R. & Tohge, T. The genetics of plant metabolism. Annu. Rev. Genet. 51, 287–310 (2017).

Singh, K., Foley, R. C. & Oñate-Sánchez, L. Transcription factors in plant defense and stress responses. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 5, 430–436 (2002).

Baloglu, M. C., Eldem, V., Hajyzadeh, M. & Unver, T. Genome-wide analysis of the bZIP transcription factors in cucumber. PLoS ONE 9, e96014 (2014).

Hurst, H. C. Transcription factors 1: bZIP proteins. Protein Profile 2, 101–168 (1995).

Jakoby, M. et al. bZIP transcription factors in Arabidopsis. Trends Plant Sci. 7, 106–111 (2002).

Fan, L., Xu, L., Wang, Y., Tang, M. & Liu, L. Genome- and transcriptome-wide characterization of bZIP gene family identifies potential members involved in abiotic stress response and anthocyanin biosynthesis in Radish (Raphanus sativus L.). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, E6334 (2019).

Zhang, Y. et al. Genome-wide analysis of the bZIP gene family in Chinese jujube (Ziziphus jujuba Mill.). BMC Genom. 21, 483 (2020).

Osterlund, M. T., Hardtke, C. S., Wei, N. & Deng, X. W. Targeted destabilization of HY5 during light-regulated development of Arabidopsis. Nature 405, 462–466 (2000).

Gangappa, S. N. et al. The Arabidopsis B-BOX protein BBX25 interacts with HY5, negatively regulating BBX22 expression to suppress seedling photomorphogenesis. Plant Cell 25, 1243–1257 (2013).

Shin, J., Park, E. & Choi, G. PIF3 regulates anthocyanin biosynthesis in an HY5-dependent manner with both factors directly binding anthocyanin biosynthetic gene promoters in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 49, 981–994 (2007).

Qiu, Z. et al. Identification of Candidate HY5-dependent and -independent regulators of anthocyanin biosynthesis in tomato. Plant Cell Physiol. 60, 643–656 (2019).

Zhang, L. et al. The HY5 and MYB15 transcription factors positively regulate cold tolerance in tomato via the CBF pathway. Plant Cell Environ. 43, 2712–2726 (2020).

Zhang, Y., Liu, Z., Liu, R., Hao, H. & Bi, Y. Gibberellins negatively regulate low temperature-induced anthocyanin accumulation in a HY5/HYH-dependent manner. Plant Signal Behav. 6, 632–634 (2011).

Li, Y. et al. FvbHLH9 functions as a positive regulator of anthocyanin biosynthesis by forming a HY5-bHLH9 transcription complex in strawberry fruits. Plant Cell Physiol. 61, 826–837 (2020).

Nguyen, N. H. et al. MYBD employed by HY5 increases PIF3 regulates anthocyanin biosynthesis in an HY5-dependent manner with both factors directly binding anthocyanin biosynthetic gene promoters in Arabidopsis accumulation via repression of MYBL2 in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 84, 1192–1205 (2015).

Zhang, Y., Zheng, S., Liu, Z., Wang, L. & Bi, Y. Both HY5 and HYH are necessary regulators for low temperature-induced anthocyanin accumulation in Arabidopsis seedlings. J. Plant Physiol. 168, 367–374 (2011).

McCallum, S. et al. Genetic and environmental effects influencing fruit colour and QTL analysis in raspberry. Theor. Appl. Genet. 121, 611–627 (2010).

Shin, D. H. et al. HY5 regulates anthocyanin biosynthesis by inducing the transcriptional activation of the MYB75/PAP1 transcription factor in Arabidopsis. FEBS Lett. 587, 1543–1547 (2013).

Dröge-Laser, W. et al. Rapid stimulation of a soybean protein-serine kinase that phosphorylates a novel bZIP DNA-binding protein, G/HBF-1, during the induction of early transcription-dependent defenses. EMBO J. 16, 726–738 (1997).

Akagi, T. et al. Seasonal abscisic acid signal and a basic leucine zipper transcription factor, DkbZIP5, regulate proanthocyanidin biosynthesis in persimmon fruit. Plant Physiol. 158, 1089–1102 (2012).

Dröge-Laser, W., Snoek, B. L., Snel, B. & Weiste, C. The Arabidopsis bZIP transcription factor family-an update. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 45, 36–49 (2018).

Zhang, Y., Xu, Z., Ji, A., Luo, H. & Song, J. Genomic survey of bZIP transcription factor genes related to tanshinone biosynthesis in Salvia miltiorrhiza. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 8, 295–305 (2018).

Zheng, J. et al. Genome-wide identification of WRKY gene family and expression analysis under abiotic stress in Barley. Agronomy 11, 521 (2021).

Bentsink, L., Jowett, J., Hanhart, C. J. & Koornneef, M. Cloning of DOG1, a quantitative trait locus controlling seed dormancy in Arabidopsis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 17042–17047 (2006).

Meier, I. & Gruissem, W. Novel conserved sequence motifs in plant G-box binding proteins and implications for interactive domains. Nucleic Acids Res. 22, 470–478 (1994).

Kim, S. et al. High ambient temperature represses anthocyanin biosynthesis through degradation of HY5. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 1787 (2017).

Dong, J. et al. Genome-wide identification of the NHX gene family in Punica granatum L. and their expressional patterns under salt stress. Agronomy 11, 264 (2021).

Zhao, K. et al. Genome-wide analysis and expression profile of the bZIP gene family in poplar. BMC Plant Biol. 21, 122 (2021).

Zhou, Y. et al. Genome-wide identification and structural analysis of bZIP transcription factor genes in Brassica napus. Genes 8, E288 (2017).

Rong, S. et al. Genome-wide identification, evolutionary patterns, and expression analysis of bZIP gene family in Olive (Olea europaea L.). Genes 11, E510 (2020).

Herath, V. & Verchot, J. Insight into the bZIP gene family in solanum tuberosum: Genome and transcriptome analysis to understand the roles of gene diversification in spatiotemporal gene expression and function. IJMS 22, 253 (2020).

Tzfira, T., Vaidya, M. & Citovsky, V. VIP1, an Arabidopsis protein that interacts with Agrobacterium VirE2, is involved in VirE2 nuclear import and Agrobacterium infectivity. EMBO J. 20, 3596–3607 (2001).

An, J.-P. et al. The bZIP transcription factor MdHY5 regulates anthocyanin accumulation and nitrate assimilation in apple. Hortic. Res. 4, 17023 (2017).

Liu, C.-C. et al. The bZIP transcription factor HY5 mediates CRY1a-induced anthocyanin biosynthesis in tomato. Plant Cell Environ. 41, 1762–1775 (2018).

Liu, W. et al. MdWRKY11 participates in anthocyanin accumulation in red-fleshed apples by affecting MYB transcription factors and the photoresponse factor MdHY5. J. Agric. Food Chem. 67, 8783–8793 (2019).

Thurow, C. et al. Tobacco bZIP transcription factor TGA2.2 and related factor TGA2.1 have distinct roles in plant defense responses and plant development. Plant J. 44, 100–113 (2005).

Li, X. et al. Two cassava basic leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factors (MebZIP3 and MebZIP5) confer disease resistance against cassava bacterial blight. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 2110 (2017).

Li, Q. et al. CsBZIP40, a BZIP transcription factor in sweet orange, plays a positive regulatory role in citrus bacterial canker response and tolerance. PLoS ONE 14, e0223498 (2019).

An, J.-P. et al. MdHY5 positively regulates cold tolerance via CBF-dependent and CBF-independent pathways in apple. J. Plant Physiol. 218, 275–281 (2017).

Iglesias-Fernández, R., Barrero-Sicilia, C., Carrillo-Barral, N., Oñate-Sánchez, L. & Carbonero, P. Arabidopsis thaliana bZIP44: A transcription factor affecting seed germination and expression of the mannanase-encoding gene AtMAN7. Plant J. 74, 767–780 (2013).

Yang, B. et al. RSM1, an Arabidopsis MYB protein, interacts with HY5/HYH to modulate seed germination and seedling development in response to abscisic acid and salinity. PLoS Genet. 14, e1007839 (2018).

Shi, Q.-M., Yang, X., Song, L. & Xue, H.-W. Arabidopsis MSBP1 is activated by HY5 and HYH and is involved in photomorphogenesis and brassinosteroid sensitivity regulation. Mol. Plant 4, 1092–1104 (2011).

Liu, H. et al. Negative regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis in tomato by MicroRNA828 under phosphate deficiency. Sci. Agric. Sin. 48, 2911–2924 (2015).

Qiu, D. et al. High throughput sequencing technology reveals that the taxoid elicitor methyl jasmonate regulates microRNA expression in Chinese yew (Taxus chinensis). Gene 436, 37–44 (2009).

Patel, P., Yadav, K., Srivastava, A. K., Suprasanna, P. & Ganapathi, T. R. Overexpression of native Musa-miR397 enhances plant biomass without compromising abiotic stress tolerance in banana. Sci. Rep. 9, 16434 (2019).

Xue, T., Liu, Z., Dai, X. & Xiang, F. Primary root growth in Arabidopsis thaliana is inhibited by the miR159 mediated repression of MYB33, MYB65 and MYB101. Plant Sci. 262, 182–189 (2017).

Ni, J. et al. Functional and correlation analyses of dihydroflavonol-4-reductase genes indicate their roles in regulating anthocyanin changes in Ginkgo biloba. Ind. Crop Prod. 152, 112546 (2020).

Liu, D., Shi, S., Hao, Z., Xiong, W. & Luo, M. OsbZIP81, a homologue of Arabidopsis VIP1, may positively regulate ja levels by directly targetting the genes in ja signaling and metabolism pathway in rice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, E2360 (2019).

Pan, F. et al. Genome-wide identification and expression analyses of the bZIP transcription factor genes in moso bamboo (Phyllostachys edulis). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, E2203 (2019).

Guan, R. et al. Draft genome of the living fossil Ginkgo biloba. Gigascience 5, 49 (2016).

Zhao, Y.-P. et al. Resequencing 545 ginkgo genomes across the world reveals the evolutionary history of the living fossil. Nat. Commun. 10, 4201 (2019).

El-Gebali, S. et al. The Pfam protein families database in 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D427–D432 (2019).

Lu, S. et al. CDD/SPARCLE: The conserved domain database in 2020. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, D265–D268 (2020).

Letunic, I., Khedkar, S. & Bork, P. SMART: Recent updates, new developments and status in 2020. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, D458–D460 (2021).

Gasteiger, E. et al. ExPASy: The proteomics server for in-depth protein knowledge and analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3784–3788 (2003).

Li, Y.-Y., Meng, D., Li, M. & Cheng, L. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the bZIP gene family in apple (Malus domestica). Tree Genet. Genomes 12, 82 (2016).

Tamura, K., Stecher, G., Peterson, D., Filipski, A. & Kumar, S. MEGA6: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 2725–2729 (2013).

Sanjari, S., Shirzadian-Khorramabad, R., Shobbar, Z.-S. & Shahbazi, M. Systematic analysis of NAC transcription factors’ gene family and identification of post-flowering drought stress responsive members in sorghum. Plant Cell Rep. 38, 361–376 (2019).

Chen, C. et al. TBtools: An integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol. Plant 13, 1194–1202 (2020).

Hu, B. et al. GSDS 2.0: an upgraded gene feature visualization server. Bioinformatics 31, 1296–1297 (2015).

Lescot, M. et al. PlantCARE, a database of plant cis-acting regulatory elements and a portal to tools for in silico analysis of promoter sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, 325–327 (2002).

Ye, J. et al. A global survey of full-length transcriptome of Ginkgo biloba reveals transcript variants involved in flavonoid biosynthesis. Ind. Crop Prod. 139, 111547 (2019).

von Mering, C. et al. STRING: A database of predicted functional associations between proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 258–261 (2003).

Zhang, W., Xu, F., Cheng, S. & Liao, Y. Characterization and functional analysis of a MYB gene (GbMYBFL) related to flavonoid accumulation in Ginkgo biloba. Genes Genom. 40, 49–61 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 31971693 and 32101563) and Hubei Key Laboratory of Economic Forest Germplasm Improvement and Resources Comprehensive Utilization, Hubei Collaborative Innovation Center for the Characteristic Resources Exploitation of Dabie Mountains Open Fund Project (202019904).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.X., W.W.Z. and J.B.Y. conceived the study and design the experimental study. H.H., Y.T.L. and L.Y. performed the experiments. M.Y.F., X.Y.Y. and Y.L.L. provided useful suggestions regarding the study. H.H. analyzed the data and wrote the original draft of this paper. W.W.Z. and J.B.Y revised the paper. All authors have read and approved the final version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Han, H., Xu, F., Li, Y. et al. Genome-wide characterization of bZIP gene family identifies potential members involved in flavonoids biosynthesis in Ginkgo biloba L.. Sci Rep 11, 23420 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-02839-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-02839-2

This article is cited by

-

Coordination among flower pigments, scents and pollinators in ornamental plants

Horticulture Advances (2024)

-

Systematic analysis and identification of regulators for SRS genes in Capsicum annuum

Plant Growth Regulation (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.