Abstract

HIV-related stigma, lack of disclosure and social support are still hindrances to HIV testing, care, and prevention. We assessed the association of these social-psychological statuses with nevirapine (NVP) and efavirenz (EFV) plasma concentrations among HIV patients in Kenya. Blood samples were obtained from 254 and 312 consenting HIV patients on NVP- and EFV-based first-line antiretroviral therapy (ART), respectively, and a detailed structured questionnaire was administered. The ARV plasma concentration was measured by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS). There were 68.1% and 65.4% of the patients on NVP and EFV, respectively, who did not feel guilty for being HIV positive. The disclosure rates were approximately 96.1% and 94.6% of patients on NVP and EFV, respectively. Approximately 85% and 78.2% of patients on NVP and EFV, respectively, received social support as much as needed. There were 54.3% and 14.2% compared to 31.7% and 4.5% patients on NVP and EFV, respectively, with supratherapeutic and suboptimal plasma concentrations. Multivariate quantile regression analysis showed that feeling guilty for being HIV positive was associated with increased 954 ng/mL NVP plasma concentrations (95% CI 192.7 to 2156.6; p = 0.014) but not associated with EFV plasma concentrations (adjusted β = 347.7, 95% CI = − 153.4 to 848.7; p = 0.173). Feeling worthless for being HIV positive was associated with increased NVP plasma concentrations (adjusted β = 852, 95% CI = 64.3 to 1639.7; p = 0.034) and not with EFV plasma concentrations (adjusted β = − 143.3, 95% CI = − 759.2 to 472.5; p = 0.647). Being certain of telling the primary sexual partner about HIV-positive status was associated with increased EFV plasma concentrations (adjusted β 363, 95% CI, 97.9 to 628.1; p = 0.007) but not with NVP plasma concentrations (adjusted β = 341.5, 95% CI = − 1357 to 2040; p = 0.692). Disclosing HIV status to neighbors was associated with increased NVP plasma concentrations (adjusted β = 1731, 95% CI = 376 to 3086; p = 0.012) but not with EFV plasma concentrations (adjusted β = − 251, 95% CI = − 1714.1 to 1212.1; p = 0.736). Obtaining transportation to the hospital whenever needed was associated with a reduction in NVP plasma concentrations (adjusted β = − 1143.3, 95% CI = − 1914.3 to − 372.4; p = 0.004) but not with EFV plasma concentrations (adjusted β = − 6.6, 95% CI = − 377.8 to 364.7; p = 0.972). HIV stigma, lack disclosure and inadequate social support are still experienced by HIV-infected patients in Kenya. A significant proportion of patients receiving the NVP-based regimen had supra- and subtherapeutic plasma concentrations compared to EFV. Social-psychological factors negatively impact adherence and are associated with increased NVP plasma concentration compared to EFV.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Although the current trend in the global HIV epidemic has stabilized, data still imply disappointingly high levels of infection, an indictment of irregular control progress in countless countries1. The HIV pandemic continues to be the leading cause of death in sub-Saharan Africa, with Kenya having the joint third-largest HIV epidemic in the world (alongside Tanzania), with 1.6 million people living with HIV1. HIV infection affects every breadth of life, including physical, psychological, social and spiritual dimensions2,3. In as much as HIV infection has been reported in Kenya for the last four decades, this infection is still dreaded by many, mainly due to misinformation about the disease and consequently the stigma and exclusion associated with the infection4. People living with HIV (PLWHA) are burdened with both medical and social problems associated with the disease5. HIV infection among a large population results in stigma for both infected and affected individuals6,7. Furthermore, infection consistently results in loss of socioeconomic status, employment, income, housing, health care and mobility5. The outcome of stigma includes but is not limited to increased secrecy (lack of disclosure) and denial, which is not only a stimulus for HIV transmission but also a cause for poor disclosure and subsequent lack or inadequate social support5,7.

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) is an integral component in reducing the burden of HIV. Globally, at the end of 2020, 67% of 38 million PLWHA were on ART1. A remarkable scale-up of ART has put Kenya on track to reach the target for AIDS-related deaths. At the end of 2020, approximately 74% of adults and 73% of children in Kenya needing ART were essentially receiving it1. A remarkable fraction of these patients (68%) had attained viral suppression (UNAIDS, 2020). At the time of this study, the first-line ART guidelines for children, youth and adults in Kenya typically contained a backbone of two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs; zidovudine [AZT], or tenofovir [TDF] with lamivudine [3TC]), plus one nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI), either nevirapine (NVP) or efavirenz (EFV)8.

Therapeutic drug exposure is a major requirement for ART management9. Suboptimal exposure to ART, especially NNRTIs (NVP and EFV), jeopardizes ART treatment success10. Generally, efavirenz and nevirapine plasma concentrations are associated with several factors, including host pharmacogenetics, as well as pharmacoecological factors, such as social-psychological status and adherence11. Although pharmacoecological factors are those that primarily affect adherence, social psychological status could independently affect ARV plasma concentration11. HIV stigma negatively affects ART utilization and the quality of care5. Social support and disclosure have been shown to significantly affect treatment outcomes in many settings4. Counselling and social support for both infected and affected people is associated with effective coping with each stage of the infection and enriches the quality of life and hence adherence to ART2. This study assessed the association between HIV stigma, disclosure and social support on ART adherence and the steady-state plasma concentrations of NVP and EFV among HIV patients receiving ART in one of the largest and oldest cosmopolitan care and treatment centers in Kenya.

Methods

Study design and setting

This was a cross-sectional study conducted between August 2016 and January 2020. The data presented in this study were part of a study that aimed to assess the pharmacogenetic and pharmacoecological etiology of suboptimal responses to nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) among HIV patients in Nairobi, Kenya. Patients were recruited in this study if they were HIV-infected adults (aged above 18 years); receiving first-line ART comprising zidovudine (AZT) or abacavir (ABC) or tenofovir (TDF) or stavudine (d4T), lamivudine (3TC), and efavirenz (EFV) or nevirapine (NVP) for at least 12 months; and willing to give voluntary written informed consent. This study was based at the Family AIDS Care and Educational Services (FACES) based at Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) in Nairobi Kenya. The ART regimen formulation and dosing used in this study were performed according to the guidelines of the Ministry of Health, National AIDS & STI Control Program8. The EFV-based ART regimen comprised the following: ABC 300 mg/3TC 150 mg combination taken twice daily plus EFV 600 mg once daily, TDF 300 mg/3TC 300 mg/EFV 600 mg one fixed dose combination taken once daily, or AZT 300 mg/3TC 150 mg combination taken twice daily plus EFV 600 mg once daily. The NVP based regimen comprised the following: ABC 600 mg/3TC 300 mg combination taken once daily plus NVP 200 mg twice daily, or TDF 300 mg/3TC 300 mg combination taken once daily plus NVP 200 mg twice daily, or AZT 300 mg /3TC 150 mg NVP 200 mg one fixed dose combination taken twice daily and D4T 30 mg/3TC 150 mg/NVP 200 mg one fixed dose combination taken twice daily. The study population and site have been described in detail in our previous publication Ngayo et al.12. This research was carried out in accordance with the basic principles defined in the Guidance for Good Clinical Practice and the Principles enunciated in the Declaration of Helsinki (Edinburg, October 2000). This protocol and the corresponding informed consent forms used in this study were reviewed, and permission was obtained from the Kenya Medical Research Institute Scientific Review Unit (SERU) (Protocol No SSC 2539). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before enrollment.

Sample size

Sample size calculation used the formula described by Lemashow13 based on population proportion estimation with specified relative precision. The alpha (α) was set at 0.05, the relative precision (ε) was set at 0.20 and the proportion of HIV-infected individuals with suboptimal NVP/EFV plasma concentrations during a 12-month ART was set at 15%14,15. A total of 599 patients were recruited to achieve 0.95 power, where recruitment of patients per treatment arm was done proportionate to size, yielding 269 and 330 patients on NVP- and EFV-based regimens, respectively.

Data collection

ART drug adherence assessment

Screening for adherence to ART in this study was conducted by review of pharmacy refill data or medical records as described by Ochieng et al.16. Adherence was measured based on dose compliance during the 30 days preceding the latest refill. The quantity of dose pills at refill was counted and reconciled against the dose counts dispensed at last refill. Furthermore, pill count data were obtained from patient cards for the four months preceding the study period. Nonadherence was determined as the percentage of overdue dose at refill, averaged over a four-month period and used to assign adherence as good (< = 5% dose skipped), fair (6–15% dose skipped) or poor (> 15% dose skipped).

Structured interviews

Structured interviews (Supplementary file) were used to collect patient-related information from all the study patients. The data collected included demographic characteristics, clinical history, HIV stigma, HIV disclosure and social support and adherence. A pilot study was conducted to test the questionnaire and other key points in the interviews. Some of the key points explored in the structured questionnaire included stigma and segregation of people living with HIV (self-worth, guilt, emotional feeling); challenges of living with HIV, such as access to health services and community life; experiences/issues with HIV disclosure and adherence to medications. The interviews were conducted by a clinician in a separated private room. The second part of the questionnaire was filled out by retrospective review of patient medical records to abstract data on the occurrence of any adverse drug reactions, evidence of treatment failures and adherence to ART.

Whole blood samples (5 mL) at 12–16 h post ARV drug dose were collected using EDTA anticoagulant tubes to determine the concentration of NVP and EFV plasma concentrations.

Determination of nevirapine and efavirenz plasma concentrations

The nevirapine and efavirenz plasma concentrations were measured using a tandem quadrupole mass spectrometer (LC/MS/MS) designed for ultrahigh performance: Xevo TQ-S (Waters Corporation, U.S. A) as described by Reddy et al.17. Plasma samples were first subjected to a thorough in-house method for the inactivation of the HIV virus. Plasma samples were extracted using Bond Elut C18 cartridges according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Agilent Technologies, USA). The eluents were then completely evaporated using Thermo Scientific™ Reacti-Vap™ Evaporators (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., USA) at 37 °C for 30 min. This was then reconstituted using 100μl100 ul of equal parts 1:1 acetonitrile and water, vortexed briefly and transferred into 50 ml capped vials and placed into Xevo TQ-S (Waters Corporation, U.S. A) for quantification. Approximately 1 μl of the samples was injected automatically into the LC/MS/MS instrument and quantified within 5 min.

Data analysis

All data were subjected to descriptive data analysis. Frequencies and percentages were used to present the sociodemographic data. The relationship between HIV stigma, disclosure and social support-related variables and ART drug adherence was first evaluated using the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. The social-psychological variables were then analyzed for association with NVP and EFV plasma concentrations. Steady-state NVP and EFV plasma concentrations were not normally distributed by the Shapiro–Wilk test; hence, the Kruskal–Wallis test and Dunn’s test and quantile regression analysis were used to evaluate variations and associations with NVP and EFV plasma concentrations at the 5% significance level. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA v 13 (StataCorp LP, Texas, USA). The NVP plasma concentrations were categorized as < 3400 ng/mL (below the therapeutic range), 3400–6000 ng/mL (therapeutic range) and > 6000 ng/mL (above the therapeutic range). For EFV, concentrations of < 1000 ng/ml were considered below the therapeutic range, 1000 to 4000 ng/ml considered the therapeutic range and > 4000 ng/ml considered supratherapeutic concentrations18,19.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the KEMRI Scientific Review Unit (SERU). The protocol number is SSC No. 2539.

Consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects before the study.

Results

Baseline characteristics of study patients

Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of the study population. The results from the 254/269 (94.4%) and 312/330 (94.5%) response rates of patients on NVP and EFV, respectively, with all the relevant data were analyzed. The median age of the patients was 41 years (IQR = 35–47 years), with a median duration of living with HIV infection of five years (IQR = 1–11 years) and a median duration since ART initiation of three years (IQR = 1–8 years). Among these patients, 342 (60.4%) were female, 379 (67%) were married, 367 (64.8%) were Bantus, and 106 (18.2%) had a previous partner who died. Only 3.5% and 5.8% and 19.7% and 17.3% (on NVP and EFV, respectively) were currently smoking and taking alcohol, respectively.

Out of 254 patients on NVP and 312 on EFV, the majority 74.4% and 73.3% stated difficulties disclosing their HIV status. In contrast, the majority (79.1% and 75.9%; 68.1% and 65.4% on NVP and EFV, respectively) did not feel immoral or guilty for being HIV positive, respectively. For patients on either NVP or EFV, the majority did not feel ashamed or worthless for being HIV positive and were very ready to tell their primary sexual partner of their HIV status. The majority, 85% (NVP) and 78.2% (EFV), were satisfied with advice received about important things in life (p = 0.022). Similarly, the majority of these patients had adequate psychosocial support in finding someone to talk to about work/household problems, about personal/family problems and had people who cared about their situations and received much love and affection. The majority of the patients also received emergency financial and transportation support, but there was no significant difference between the ART regimens.

ART adherence

Among all the study patients, 371 (n = 566; 65.6%), 164 (n = 254; 64.6%) on NVP and 207 (n = 312; 66.3%) on EFV were categorized as poor adherence to ART (Fig. 1).

Efavirenz and Nevirapine plasma concentration

Among the patients on the nevirapine-based ART regimen, the majority 138 (n = 254; 54.3%) had plasma concentrations of > 6000 ng/ml, which are considered levels for durable viral suppression. There were 80 (n = 254; 31.5%) patients with NVP concentrations between 3400 and 6000 ng/ml considered levels for viral mutant selection windows and a few 3 (n = 254; 14.2%) who had NVP plasma concentrations of < 3400 ng/ml considered levels for poor viral suppression (p = 0.0001). For patients on the efavirenz-based ART regimen, the majority 199 (n = 312; 63.8%) had plasma concentrations between 1000 and 4000 ng/ml considered levels for viral mutant selection windows followed by 99 (n = 312; 31.7%) with EFV plasma concentrations of > 4000 ng/ml considered levels for durable viral suppression. Fourteen (n = 312; 4.5%) patients had EFV plasma concentrations of < 1000 ng/ml, which are considered concentrations for a poor viral suppression window (p < 0.05).

There was no significant difference in NVP plasma concentrations across dosing formulations (p = 0.248) or among EFV dosing formulations (p = 0.352) (Table 2).

Relationship between HIV-related stigma, disclosure and social support and ART adherence

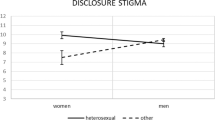

The HIV stigma-related factors associated with adherence to NVP-based regimens included feeling guilty for being HIV positive, hiding HIV status from others and feeling certain to tell primary sexual partners about HIV status. Feeling immoral for being HIV positive and feeling certain to tell primary sexual partners about HIV status was associated with adherence to EFV-based regimens.

Being able to disclose HIV status to anyone and to family members was associated with adherence to EFV-based regimens. The majority of HIV social support-related factors, including getting useful advice about important things in life, getting a chance to talk to someone about work or household problems, getting love and affection, was associated with ART adherence to both NVP- and EFV-based regimens (Table 2).

Variation in median nevirapine and efavirenz plasma concentrations and HIV stigma, disclosure and social support-related factors

Table 3 summarizes the variation in the median NVP and EFV plasma concentrations and sociodemographic, sexual behavior, HIV stigma and disclosure characteristics. Patients who disclosed their HIV status to their employer had higher median (IQR) EFV plasma concentrations (3157, IQR = 2001–5976 ng/mL) than those who did not (2173.5, IQR = 1655.5–3208.5 ng/mL; p = 0.041). Patients who did not disclose their HIV status to religious leaders had higher median (IQR) EFV plasma concentrations (2821.5, IQR = 1945–5270 ng/mL) than those who did (1998.5, IQR = 1548–2520 ng/mL; p = 0.0031). Furthermore, patients who disclosed their HIV status to the public had higher median (IQR) EFV plasma concentrations (3097, IQR = 2872–5976 ng/mL) than patients who did not (1965, IQR = 1639–2763 ng/mL; p = 0.0117).

Patients with higher median (IQR) EFV plasma concentrations were those who did not feel guilty for being HIV positive (6511, IQR = 4607–9863 ng/mL) compared to patients who felt guilty (5557, IQR = 4247–7633 ng/mL; p = 0.0163). Patients who disclosed their HIV status to their spouse (6402.5, IQR = 4564.5–9180.5 ng/mL) had higher median (IQR) NVP plasma concentrations than those who did not (4853, IQR = 3450–6202 ng/mL; p = 0.0362).

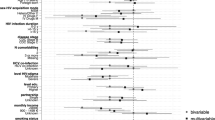

Factors associated with drug plasma concentrations

Stigma

In multivariate quantile regression analysis, feeling guilty for being HIV positive (adjusted β = 954, 95% CI = 192.7 to 2156.6; p = 0.014) or feeling worthless for being HIV positive (adjusted β = 852, 95% CI = 64.3 to 1639.7; p = 0.034) were independent factors associated with increased NVP plasma concentrations. For patients on EFV, being certain of telling the primary sexual partner about HIV-positive status was associated with increased EFV plasma concentrations (adjusted β 363, 95% CI, 97.9 to 628.1; p = 0.007) (Table 4).

Disclosure

In multivariate quantile regression analysis, disclosing patients’ HIV status to neighbors (adjusted β = 1731, 95% CI = 376 to 3086; p = 0.012) was associated with increased NVP plasma concentrations. None of the HIV disclosure-related factors were associated with EFV plasma concentrations (Table 4).

Social support

In multivariate quantile regression analysis, transportation to the hospital whenever needed (adjusted β = − 1143.3, 95% CI = − 1914.3 to − 372.4; p = 0.004) was associated with lower NVP plasma concentrations. None of the HIV social support-related factors were found to be associated with EFV plasma concentrations (Table 4).

Discussion

Every blueprint and policies geared towards individualization of ART treatment aimed at prolonging the life of HIV patients contributes significantly to the components of HIV treatment programs in many countries, including Kenya. The recommendation by the World Health Organization (WHO) requiring testing and treatment of all HIV-positive patients regardless of their CD4 or viral load20 must also appreciate that optimal ART outcomes require an in-depth understanding of the individual’s variation in response to ART, both efficacy and toxicity. The concentration of ARV drug found in plasma has been shown to affect the rate at which ARVs begin to suppress viral replication and/or the duration of the effect on viral replication21. Therapeutic drug concentrations are therefore a key to successful ART14. Low drug concentrations observed in patients on ART are related to failure to achieve immediate virologic success and longer-term immunological failure22. ARV drug plasma concentrations are associated not only with patients’ pharmacogenetic and pharmacoecological factors23 but also to social psychological (defined as human behavior as a result of the relation between mental state and social situation) well-being of patients. Stigma, disclosure and social support are social psychological—mental representations are important influence of our interactions with others and environment. This is among the first studies to assess the association between HIV stigma (a mark of disgrace, discounting, discrediting and discriminating associated with HIV infection and ARV use)24, HIV disclosure (action of making new or secret of being HIV positive known) and HIV social support (the perception and actuality that one is cared for or having assistance available from other people) on the steady-state plasma concentrations of nevirapine and efavirenz among HIV patients receiving treatment in Nairobi Kenya.

HIV stigma, disclosure and availability of social support are key determinants of patients’ behavior and are associated with adherence to HIV care, treatment and prevention. Previously, in Kenya, involvement in community support networks considerably enriched adherence and treatment outcome25. Furthermore, patients vigorously partaking in community support networks tended to attain peak NVP plasma concentrations early hours postdosing, which were markedly higher than those seen in patients not actively involved in community support networks. Countless studies have interconnected social support to better medication adherence and better clinical outcomes26.

The association of patients’ social psychological status with ARV plasma concentration and treatment outcomes might be multifactorial. Social psychological status could indirectly be associated with ARV plasma concentration and treatment outcomes by affecting adherence to ART25,27,28. In this study, social psychological factors were significantly associated with adherence among patients on EFV compared to those on NVP. The EFV-based regimen is prescribed as a fixed-dose, single-tablet regimen, while NVP is prescribed as two or more pills per day8. It is possible that the higher pill burden among patients on NVP could be associated with the patient’s social psychological status and adherence and hence NVP plasma concentration. Studies have related a lower pill burden with both better adherence and virological suppression29,30 as well as patients’ emotional satisfaction31. Although not investigated in this study, studies have reported a common cause between social psychological status and non-adherence, both of which could independently be associated with ARV plasma concentration27,28. Reverse causality is also possible; efavirenz is associated with high rates of neuropsychiatric side effects, including vivid dreams, insomnia and mood changes, which could impact internal feelings of shame and interest in seeking social support32. It is presumed that this neuropsychiatric effect of EFV could affect treatment outcomes, including ARV plasma concentration.

HIV-associated stigma-related factors such as feeling guilty and worthless for being HIV positive were associated with higher median NVP plasma concentrations. For patients on an EFV-based regimen, those who were certain to reveal their HIV status to their primary sexual partner had better ART adherence accompanied by higher median EFV plasma concentrations. Stigma and discrimination remain the paramount challenges confronted by people living with HIV/AIDS33. Although data are skewed on the association between HIV stigma and NNRTI plasma concentrations, stigma and discrimination negatively affect people living with HIV34. HIV-related stigma is a wide-ranging and worldwide social phenomenon that is exhibited within multiple social spheres, including healthcare encompassing denial of care or treatment, HIV testing without consent, confidentiality breaches, negative attitudes and humiliating practices by health workers35. Studies have shown an association between HIV stigma and poorer physical and mental health outcomes27. Stigma has also been linked with secondary health-related factors, including seeking healthcare and adherence to antiretroviral therapy and access to and usage of health and social services27,28. Inevitably, these negative outcomes of stigma are bound to affect the overall treatment outcomes in terms of therapeutic monitoring.

HIV status disclosure to anyone and family members in this study was associated with ART adherence to an EFV-based regimen and not NVP. In multivariate analysis, disclosure of HIV status to neighbors was associated with increased median NVP plasma concentration. Patients on EFV with lower pill count are more likely to disclose HIV status compared to those on NVP-based regimens, hence better adherence and better treatment outcomes29,30. Contrary to our study, in Thailand, Sirikum et al.36 reported no significant difference in the median ART adherence by pill count, CD4 count, or HIV viral load between HIV patients who disclosed their status compared to those who did not. Studies have shown that HIV disclosure has two possible treatment outcomes37. On the one hand, HIV status disclosure to sexual partners is a vital prevention target underlined by both the WHO and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)38. At an individual level and to the general public, HIV disclosure is accompanied by numeral benefits36. HIV infection disclosure to sexual partners is associated with less anxiety and increased social support, especially among women37,38. Further, HIV status disclosure is accompanied by improved access to HIV prevention and treatment programs, increased opportunities for risk reduction and increased opportunities to plan for the future. Disclosure of HIV status also expands the awareness of HIV risk to untested partners, leading to better acceptance and utilization of voluntary HIV testing and counselling and changes in HIV risk behaviors37,38. In addition, disclosure of HIV status to sexual partners empowers couples to make educated reproductive health choices that may eventually lower the number of unintended pregnancies among HIV-positive women37. Along with these benefits, however, there are a number of potential risks from disclosure for HIV-infected women, including loss of economic support, blame, abandonment, physical and emotional abuse, discrimination and disruption of family relationships37,38. These risks may lead women to choose not to share their HIV test results with their friends, family and sexual partners. This, in turn, leads to lost opportunities for the prevention of new infections and for the ability of patients, especially women, to access appropriate treatment, care and support services where they are available37,38.

In our study, patients who had adequate social support, such as getting useful advice about important things in life, having a chance to talk to someone about work, household, personal or family problems, getting love and affection, had higher median NVP and EFZ plasma concentrations. In South Africa, Brittain et al.39 showed a correlation between social support and stigma influencing the development of depressive symptoms. The importance of community support networks in enhancing social relationships demystifying HIV-associated stigma is well documented40,41. Evidence shows the positive effects of social support and protection on other HIV-related outcomes, such as sexual risk behaviors42,43, mental health distress and family relationships44,45. Growing evidence of associations between social protection and HIV risk reduction46 is reflected in a number of policy documents by UNICEF, UNAIDS and PEPFAR-USAID that focus on pediatric and adolescent HIV prevention47,48.

Some of the important limitations worth mentioning in this study included. First, the use of NVP-based ART regimens in Kenya and other countries, especially developed countries, has been considerably reduced in the recent past, meaning that this study could be relevant to a restricted number of patients. Second, standardized tools for measuring stigma, disclosure and social support were not used in this study, limiting the generalizability of this study outcomes. Third, this was a cross-sectional study, which only permitted the description of the relationship between the three sociopsychological factors and NVP/EFV plasma concentrations and not a causal conclusion. Such outcomes can be confirmed in a longitudinal study.

Conclusions

This study, conducted in one of the oldest and largest cosmopolitan treatment centers in Kenya, shows that HIV stigma, lack of disclosure and inadequate social support are still noticeable among HIV-infected patients in Kenya. The NVP plasma concentrations were highly heterogeneous, with a significant proportion of patients having supratherapeutic and subtherapeutic plasma concentrations compared to those on EFV regimens. Social-psychological factors negatively impact adherence and are associated with increased NVP plasma concentration compared with EFV.

Data availability

All data will be stored at figshare at the moment submitted as electronic data.

References

UNAIDS. 2020. Global AIDS update 2020. Seizing the Moment. Tackling entrenched Inequalities to end epidemics. Available https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2020_global-aids-report_en.pdf. Accessed August 16, 2020.

WHO. HIV/AIDS Psychosocial Support. Available at https://www.who.int/hiv/topics/psychosocial/support/en/#references. Accessed March 7, 2021.

Okonji, E. F., Mukumbang, F. C., Orth, Z., Vickerman-Delport, S. A. & Van Wyk, B. Psychosocial support interventions for improved adherence and retention in ART care for young people living with HIV (10–24 years): A scoping review. BMC Public Health 20(1), 1841 (2020).

Kose, S., Mandiracioglu, A., Mermut, G., Kaptan, E. & Ozbel, Y. The social and health problems of people living with HIV/ AIDS in Izmir. Turkey. EAJM. 44, 32–39 (2012).

Mbonu, N. C., van den Borne, B. & De Vries, N. Stigma of people with HIV/AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa: A literature review. J. Trop. Med. 14, 1–14 (2009).

Greeff, M. et al. Disclosure of HIV status: Experiences and perceptions of persons living with HIV/AIDS and nurses involved in their care in Africa. Qual. Health Res. 18(3), 311–324 (2008).

Rankin, W., Brennan, S., Schell, E., Laviwa, J. & Rankin, S. The stigma of being HIV-positive in Africa. PLoS Med. 8, e247 (2005).

Ministry of Health, National AIDS & STI Control Program. Guidelines on Use of Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating and Preventing HIV Infection in Kenya 2018 Edition. Nairobi, Kenya: NASCOP, August 2018. Print.

Veldkamp, A. I. et al. High exposure to nevirapine in plasma is associated with an improved virological response in HIV-1-infected individuals. AIDS 15(9), 1089–1095 (2001).

Mur, E., Droste, J. A., Bosch, M. & Burger, D. M. Nevirapine plasma concentrations are still detectable after more than 2 weeks in the majority of women receiving single-dose nevirapine: Implications for intervention studies. J. Acquir Immune Defic. Syndr. 39(4), 419–421 (2005).

Pavlos, R. & Phillips, E. J. Individualization of antiretroviral therapy. Pharmgenom. Pers. Med. 5(1), 1–17 (2012).

Ngayo, M. O. et al. Impact of first line antiretroviral therapy on clinical outcomes among HIV-1 infected adults attending one of the largest hiv care and treatment program in Nairobi Kenya. J. AIDS Clin. Res. 7, 615 (2016).

Lemeshow, S., Hosmer, D. W., Klar, J. & Lwanga, S. K. Adequacy of sample size in health studies (John Wiley & Sons, 1990).

Gunda, D. W. et al. Plasma concentrations of efavirenz and nevirapine among HIV-infected patients with immunological failure attending a tertiary Hospital in North-Western Tanzania. PLoS ONE 8(9), e75118 (2013).

Oluka, M. N., Okalebo, F. A., Guantai, A. N., McClelland, R. & Graham, S. M. Cytochrome P450 2B6 genetic variants are associated with plasma nevirapine levels and clinical response in HIV-1 infected Kenyan women: a prospective cohort study. AIDS Res. Ther. 12, 10 (2015).

Ochieng, W. et al. Implementation and operational research: correlates of adherence and treatment failure among kenyan patients on long-term highly active antiretroviral therapy. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 69(2), e49–e56 (2015).

Reddy, S. et al. A LC–MS/MS method with column coupling technique for simultaneous estimation of lamivudine, zidovudine, and nevirapine in human plasma. J. Anal. Sci. Technol. 7, 17 (2016).

Duong, M. et al. Usefulness of therapeutic drug monitoring of antiretrovirals in routine clinical practice. HIV Clin. Trials. 5(4), 216–223 (2004).

Gopalan, B. P. et al. Sub-therapeutic nevirapine concentration during antiretroviral treatment initiation among children living with HIV: Implications for therapeutic drug monitoring. PLoS ONE 12(8), e0183080 (2017).

UNAIDS (2016) 'Prevention Gap Report'. Available at http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2016-prevention-gap-report_en.pdf. (Accessed Jan 2021).

Davis, N. L. et al. Antiretroviral drug concentrations in breastmilk, maternal HIV Viral Load, and HIV transmission to the infant: Results from the BAN study. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 80(4), 467–473 (2019).

Boulle, A. et al. Antiretroviral therapy and early mortality in South Africa. Bull World Health Organ. 86(9), 678–687 (2008).

Phillips, E. J. & Mallal, S. A. Personalizing antiretroviral therapy: Is it a reality?. In Per. Med. 6(4), 393–408 (2009).

Goffman, E. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity (Simon and Schuster, 2009).

Ochieng, W. et al. Implementation and operational research: correlates of adherence and treatment failure among Kenyan patients on long-term highly active antiretroviral therapy. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 69(2), 49–56 (2015).

Gonzalez, D. et al. Nevirapine plasma exposure affects both durability of viral suppression and selection of nevirapine primary resistance mutations in a clinical setting. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49, 3966–3969 (2005).

Chambers, L. et al. Stigma, HIV and health: a qualitative synthesis. BMC Public Health 15, 1–17 (2015).

Sears, B. HIV discrimination in health care services in Los Angeles County: The results of three testing studies. Wash Lee J. Civ. Rts Soc. Just. 15, 85 (2008).

Sax, P. E., Meyers, J. L., Mugavero, M. & Davis, K. L. Adherence to antiretroviral treatment and correlation with risk of hospitalization among commercially insured HIV patients in the United States. PLoS ONE 7(2), e31591 (2012).

Nachega, J. B. et al. Lower pill burden and once-daily antiretroviral treatment regimens for HIV infection: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin. Infect. Dis. 58(9), 1297–1307 (2014).

Truong, W. R., Schafer, J. J. & Short, W. R. Once-daily, single-tablet regimens for the treatment of HIV-1 infection. P T. 40(1), 44–55 (2015).

Kenedi, C. A. & Goforth, H. W. A systematic review of the psychiatric side-effects of efavirenz. AIDS Behav. 15, 1803–1818 (2011).

Stutterheim, S. et al. Psychological and social correlates of HIV status disclosure: the significance of stigma Visibility. AIDS Educ. Prev. 23(4), 382–392 (2011).

Rueda, S. et al. Examining the associations between HIV- related stigma and health outcomes in people living with HIV/AIDS: a series of meta-analyses. BMJ Open 6, e011453 (2016).

Rao, D. et al. A structural equation model of HIV-related stigma, depressive symptoms, and medication adherence. AIDS Behav. 16, 711–716 (2012).

Sirikum, C. et al. HIV disclosure and its effect on treatment outcomes in perinatal HIV-infected Thai children. AIDS Care 26(9), 1144–1149 (2014).

Medley, A., Garcia-Moreno, C., McGill, S. & Maman, S. Rates, barriers and outcomes of HIV serostatus disclosure among women in developing countries: implications for prevention of mother-to-child transmission programmes. Bull. World Health Organ. 82, 299–307 (2004).

Johns, D. M., Bayer, R. & Fairchild, A. L. Evidence and the politics of deimplementation: The rise and decline of the “Counseling and Testing” paradigm for HIV prevention at the US centers for disease control and prevention. Milbank Q. 94(1), 126–162 (2016).

Brittain, K. et al. social support, stigma and antenatal depression among HIV-infected pregnant women in South Africa. AIDS Behav. 21, 274–282 (2017).

Campbell, C., Yugi, N. & Sbongile, M. Building contexts that support effective community responses to HIV/AIDS: A South African case study. Am. J. Community Psychol. 39(3–4), 347–363 (2007).

Zachariah, R. et al. Community support is associated with better antiretroviral treatment outcomes in a resource-limited rural district in Malawi. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 101(1), 79–84 (2007).

Handa, S., Halpern, C. T., Pettifor, A. & Thirumurthy, H. The government of Kenya’s cash transfer program reduces the risk of sexual debut among young people age 15–25. PLoS ONE 9(1), e85473 (2014).

Cluver, L. et al. Achieving equity in HIV-treatment outcomes: can social protection improve adolescent ART-adherence in South Africa?. AIDS Car. 28(sup2), 73–82 (2016).

Bhana, A. et al. The VUKA family program: Piloting a family-based psychosocial intervention to promote health and mental health among HIV infected early adolescents in South Africa. AIDS Care – Psych. Socio-Med. Aspects AIDS/HIV. 26(1), 1–11 (2014).

Kilburn, K., Thirumurthy, H., Halpern, C. T., Pettifor, A. & Handa, S. Effects of a large-scale unconditional cash transfer program on mental health outcomes of young people in Kenya. J. Adoles. Health. 58(2), 223–229 (2016).

Pettifor, A., Rosenberg, N. & Bekker, L. G. Can cash help eliminate mother-to-child HIV transmission?. Lancet HIV. 3(2), e60-62 (2016).

UNAIDS. HIV and social protection guidance note. Retrieved from Geneva. 2014. Available at https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2014unaidsguidancenote_HIVandsocialprotection_en.pdf. Accessed March 8, 2021.

PEPFAR. (2015). Preventing HIV in adolescent girls and young women: Guidance for PEPFAR country teams on the DREAMS partnership. Washington, DC: USAID-PEPFAR. Available at http://childrenandaids.org/sites/default/files/2018-11/Preventing%20HIV%20in%20adolescent%20girls%20and%20young%20women%20-%20Guidance%20for%20PEPFAR%20country%20teams%20on%20the%20DREAMS%20Partnership.pdf. Accessed February 2, 2021.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the study patients enrolled at the FACES-KEMRI HIV care and treatment program as well as the technical staff at KEMRI and the Retrovirology, Centre de Recherche Public de la Santé (CRP-Santé), Luxembourg. We wish to acknowledge Assistant Director CMR and the Director General KEMRI for allowing the publication of this work.

Funding

This study was supported by funds from KEMRI-Internal Grant (IRG/20) 2010/2011 and HIV Research Trust Scholarship (HIVRT13-091).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.O.N., M.O. conceived the study. M.O.N. collected samples and conducted laboratory analysis. M.O., W.D.B. and F.A.O. supervised laboratory analysis. M.O.N. analyzed the data and prepared the draft manuscript. M.O., W.D.B. and F.A.O. provided guidance and mentorship during the implementation of the study. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ngayo, M.O., Oluka, M., Bulimo, W.D. et al. Association between social psychological status and efavirenz and nevirapine plasma concentration among HIV patients in Kenya. Sci Rep 11, 22071 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-01345-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-01345-9

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.