Abstract

Although the Mediterranean Sea covers approximately a 0.7% of the world’s ocean area, it represents a major reservoir of marine and coastal biodiversity. Among marine organisms, sponges (Porifera) are a key component of the deep-sea benthos, widely recognized as the dominant taxon in terms of species richness, spatial coverage, and biomass. Sponges are evolutionarily ancient, sessile filter-feeders that harbor a largely diverse microbial community within their internal mesohyl matrix. In the present work, we firstly aimed at exploring the biodiversity of marine sponges from four different areas of the Mediterranean: Faro Lake in Sicily and “Porto Paone”, “Secca delle fumose”, “Punta San Pancrazio” in the Gulf of Naples. Eight sponge species were collected from these sites and identified by morphological analysis and amplification of several conserved molecular markers (18S and 28S RNA ribosomal genes, mitochondrial cytochrome oxidase subunit 1 and internal transcribed spacer). In order to analyze the bacterial diversity of symbiotic communities among these different sampling sites, we also performed a metataxonomic analysis through an Illumina MiSeq platform, identifying more than 1500 bacterial taxa. Amplicon Sequence Variants (ASVs) analysis revealed a great variability of the host-specific microbial communities. Our data highlight the occurrence of dominant and locally enriched microbes in the Mediterranean, together with the biotechnological potential of these sponges and their associated bacteria as sources of bioactive natural compounds.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Several marine organisms, such as macro and microalgae, sponges and fishes have developed various defence mechanisms during their evolution, including the exploitation of a large variety of natural molecules. In addition to their ecological roles, these compounds display several biological activities, such as anticancer, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antimicrobial, antihypertensive, making them good candidates for biotechnological applications in the pharmaceutical, nutraceutical and cosmeceutical fields1. Marine sponges are multicellular, benthic and generally sessile organisms, spread throughout the seabed, from the tropics to the poles. In the 1950s, the interest in sponges was relighted thanks to the discovery of new bioactive nucleosides (spongotimidine and spongouridine) in the marine sponge Tectitethya crypta (i.e., Tethya cripta)2. These nucleosides were the basis for the synthesis of Ara-C, the first marine antitumor agent and antiviral drug3. It is important to consider that marine sponges are known for hosting microbial communities whose composition can be quite complex4. These symbiotic bacteria are usually involved in carbon and nitrogen fixation, nitrification, anaerobic metabolism, stabilization of the sponge skeleton, protection against UV. However, they are mainly responsible for the production of bioactive metabolites5. For example, it has been demonstrated that a Alphaproteobacteria symbiotic of the sponge Dysidea avara produce an inhibitor of angiogenesis 2-methylthio-1,4-naphthoquinone6. The structural classes of natural products commonly associated with microbial sources include non-ribosomal peptides (penicillin and vancomycin), polyketides (erythromycin and tetracycline) and hybrid peptide polyketides (cyclosporin A and rapamycin). Some of these molecules are synthesized by non-ribosomal peptide synthases (NRPSs) and polyketide synthases (PKSs), which are encoded by genes clustered in the genome7,8. Several studies have highlighted the biotechnological potential of bacterial communities in marine sponges through the identification of PKSs and NRPSs genes, encoding for secondary metabolites9,10,11,12,13.

Concerning the phylum Porifera, the Mediterranean is known to host a huge biodiversity, counting about 700 species14 and more than half of these live in the coralligenous (a hard bottom of biogenic origin mainly produced by the accumulation of calcareous encrusting algae)15,16,17. Unfortunately, anthropogenic activities together with climate changes are strongly impacting the biodiversity of the Mediterranean18,19 and, as a consequence, this facilitates the spreading of alien species20. Examples of these environmental events are Paraleucilla magna, a sponge firstly described in 2004 off the Brazilian waters and now widespread in many areas of the Mediterranean21.

In the present work, we aim at deeper exploring the microbial communities associated with sponges in the Mediterranean Sea. Eight species of sponges were collected from four different areas of the Mediterranean, in Italy: Faro Lake (in Sicily) and “Porto Paone”, “Secca delle fumose”, “Punta San Pancrazio” (in the Gulf of Naples). Species characterization was performed by morphological observation of the skeleton and amplification of several conserved molecular markers (18S and 28S rRNA, ITS and CO1), with the only exception of Geodia cydonium, which has been previously characterized22,23,24. In order to analyse the biodiversity of symbiotic communities among different sampling sites, we performed a metataxonomic analysis of sponge samples through an Illumina MiSeq platform. More than 1500 bacterial isolates from eight samples were phylogenetically identified to understand if they were host-specific and/or site-specific. The ASVs analysis was then discussed to evaluate the biotechnological potential of sponges under investigation, in view of literature data.

Results

Morphological identification

All eight studied sponges belong to the class Demospongiae (Table 1). Seven species commonly live in the Mediterranean Sea, while Oceanapia cf. perforate (Sarà, 1960) is a rare species distributed in the western Mediterranean.

Molecular characterization

BLAST similarity search corresponded with the morphological identification achieved with two (S.spi and E.dis) of the three sponge samples collected in the Faro Lake (Sicily; see Tables S1-S2). In particular, molecular analyses confirmed S.spi as Sarcotragus spinosulus and E.dis as Erylus discophorus. ITS region displayed the best alignment for the identification of S.spi specimen with 98% of identity. Concerning the sample O.per, collected in the same site, the sequence of the species Oceanapia cf. perforata, identified by morphological analysis was not available in GenBank. Nevertheless, 18S and 28S rRNA primer pairs allowed a partial identification at the genus level, with high similarity to Oceanapia isodictyiformis, plus several hits annotated as Oceanapia sp. at low percentage of identity (Tables S1-S2).

In the case of sponges collected from “Porto Paone” in the Gulf of Naples, CO1 and 18S rRNA were the best molecular markers since they allowed the identification of sponges at the species level. Concerning T.aur sample, the species Tethya aurantium was identified (95% of identities) by CO1, whereas the sample A.dam, collected in the same site, was well identified as Axinella damicornis by 18S rRNA primers, producing a high percentage of sequence similarity (99%) (Tables S1-S2).

Molecular analysis confirmed the samples A.acu and A.oro, as Acanthella acuta and Agelas oroides, respectively, with 28S and 18S rRNA reporting the highest percentage of sequence similarity (100%) (Tables S1-S2). Alignments are reported in Figures S1-S7.

Diversity analysis

Alpha rarefaction on the observed features and three diversity indices (Chao1, Shannon and Simpson), were used to determine whether each sample was sequenced up to a sufficient depth. Rarefaction curves indicated that the majority of taxa was captured, since all samples under analysis reached a plateau (Fig. 1; Figure S8). Alpha diversity within each sample, measured through diversity indices at the family, genus and species levels, revealed a considerable bacterial diversity for all sponges under analysis, particularly when the species were considered (Table S3). When the impact of the abiotic features (temperature, pH and salinity) was examined, no statistical differences were observed between the groups. Overall, PERMANOVA analysis revealed that the environmental features did not affect the species composition or abundance in the symbiotic community.

Further, a principal component analysis (PCA) was performed to reveal the bacterial species that greater contributed to the clustering of samples (Fig. 2). PCA showed seven components, with eigenvalues of 87.57, 21.42,19.12, 11.49, 10.82, 8.48, and 8.11. The first two components, including around 65.2% of the inertia of data, were used for further analyses, in order to detect the most interesting patterns. Firstly, PCA displayed three major groups, with 167 bacterial species that particularly influenced the clustering (Fig. 2).

PCA analysis—Biplot of individuals (n = 8) and explanatory variables (n = 167) of two principal components (PC1 and PC2) of metataxonomic data. The majority of species diversity is explained by the first three PCs (76.7%), with PC1 and PC2 having the highest contribution (PC1 = 52.4% and PC2 = 12.8%). Biplot shows the PCA scores of the explanatory variables as vectors (in red) and individuals grouped for salinity class (S38 = Gulf of Naples, S31 = Strait of Messina). The circle represents the equilibrium of variables contribution. The importance of each variable is reflected by the magnitude of the corresponding values in the eigenvectors (higher magnitude-higher importance). Vectors pointing towards similar (small angle) and opposite directions (0 to 180 degrees) indicate positively or negatively correlated variables, and vectors at approximately right angles (90 to 270 degrees) suggest a low correlation. Sample IDs: O.per = Oceanapia cf. perforata, S.spi = Sarcotragus spinosulus, E.dis = Erylus discophorus, A.oro = Agelas oroides, T.aur = Tethya aurantium, A.dam = Axinella damicornis and A.acu = Acanthella acuta.

Moreover, the sponge A. acuta (indicated as A.acu) clearly segregated, with several bacterial species (red vectors) contributing to the clustering (Fig. 2). Several taxa, such as Proteobacteria, Bacteroidia, Actinobacteria, Gracilibacteria, Cyanobacteria, Flavobacteria, Verrucomicrobiae, Campylobacteria, Planctomycetacia, Phycisphaerae, Nitrososphaeria, greatly affected the separation from the other sponges under analysis (Fig. 2). On the other hand, G. cydonium, T. aurantium and A. damicornis (reported as G.cyd, T.aur and A.dam, respectively), clustered into another group, where the bacteria belonging to the classes Anaerolineae, Alphaproteobacteria (Rhodobacteraceae, Hyphomicrobiaceae, Hyphomonadaceae, Kiloniellaceae, Magnetospiraceae families) and Gammaproteobacteria (Colwelliaceae and Vibrionaceae families) particularly contributed to the divergence (Fig. 2). The third cluster, corresponding to O. cf. perforata, S. spinosulus, E. discophorus and A. oroides (indicated as O.per, S.spi, E.dis and A.oro, respectively), was chacterized by an abundance of bacteria included into the phyla Proteobacteria, Chloroflexi, Tectomicrobia and Acidobacteria (Fig. 2).

Taxonomic profiling

ASVs analysis was performed on those reporting a confidence percentage ≥ of 75%. The full taxonomy of sponge samples was reported in Tables S4-S11. Among the sponges collected in the Faro Lake (Sicily) was found i. the largest number of features (142) in E. discophorus, especially Acidimicrobiia, Gemmatimonadetes, Nitrospira, Acidobacteria and Gammaproteobacteria (Fig. 3); ii. 111 ASVs in S. spinosulus, with a greater abundance of Dehalococcoidia, Anaerolineae, Acidimicrobiia, Dadabacteriia, Rhodothermia and Gammaproteobacteria (Fig. 3); iii. 109 ASVs in Oceanapia cf. perforata, where Verrucomicrobiae, Clostridium, Deltaproteobacteria, Nitrospirae, Dehalococcoidia, Anaerolineae, Thermoanaerobaculia, Acidimicrobiia, Gemmatimonadetes and Deltaproteobacteria were highly represented (Fig. 3).

Heat-map comparing the abundance of the most representative bacterial classes identified from O. cf. perforata (O.per), S. spinosulus (S.spi), E. discophorus (E.dis), A. oroides (A.oro), T. aurantium (T.aur), A. damicornis (A.dam), A. acuta (A.acu) and G. cydonium (G.cyd). Color code: green = high number of features, pink = low number of features. Taxonomy code: R = regnum, P = phylum, C = class. Heat-map was performed using GraphPad Prism V. 9 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA).

In sponges T. aurantium and A. damicornis, both collected in the Porto Paone, in the Gulf of Naples, 76 and 98 ASVs were detected, respectively. The most abundant bacterial classes in T. aurantium were Alphaproteobacteria, Gammaproteobacteria, Acidimicrobiia and Dadabacteriia, whereas bacterial community of A. damicornis was dominated by Gammaproteobacteria, Nitrospira and Deltaproteobacteria (Fig. 3).

Among the sponges collected in Punta San Pancrazio (Ischia island, Bay of Naples), A. acuta, showed 316 features, with a few abundant classes (Gammaproteobacteria, Nitrospira, Alphaproteobacteria and Acidimicrobiia) and a long tail of extremely low ASVs (Fig. 4; Figure S9). In contrast, A. oroides mainly revealed five bacterial groups (Dehalococcoidia, Anaerolineae, Gammaproteobacteria, Dadabacteria and Deltaproteobacteria), with a total of 198 ASVs (Fig. 4; Figure S9).

G. cydonium, collected in “Parco Sommerso” of Baia (Bay of Naples), showed 144 ASVs with a significant abundance of Gammaproteobacteria, Poribacteria and Nitrospira (Fig. 3).

Specifically, the taxonomic composition revealed an abundance of Proteobacteria and Cloroflexi found in O. cf. perforata (4%, respectively), S. spinosulus (3% and 4%, respectively) and A. oroides (3% and 4% respectively) (Fig. 4; Figure S9).

Differently, a high percentage (17–20%) of Actinobacteria and Proteobacteria were detected in E. discophorus. In addition, T. aurantium revealed 14% of an unknown phylum, and low percentages (5%) of another phylum (Proteobacteria) (Fig. 4; Figure S9). The sponge A. damicornis revealed 12% of Gammaproteobacteria class, while a low percentage (1%) of Nitrospirae phylum. The sponge A. acuta revealed 16% of Proteobacteria phylum and 1% of Nitrospirae phylum. Interestingly, this sponge was the only species revealing a certain abundance of Archea belonging to the phylum Thaumarchaeota (Fig. 4; Figure S9). Concerning G. cydonium, the most abundant class was Dehalococcoidia with 29.1% and Gammaproteobacteria with 19.4% (Fig. 4; Figure S9).

As reported above, the sponges O. cf. perforata, S. spinosulus, A. oroides and G. cydonium revealed a similar composition in bacterial species distribution. In fact, a high abundance of Cloroflexi and Proteobacteria was observed in these species (Fig. 4; Figure S9).

The absolute abundance of each bacterial phylum retrieved from the eight sponge samples was reported in Table S12.

Discussion

In this study we analyzed the biodiversity of marine sponges in the Mediterranean, focusing on four sampling sites: one in the Messina Strait (North–East of Sicily) and three in the Gulf of Naples. This work represents an important step forward in the investigation of the Mediterranean, being considered as a biodiversity hotspot25. Long-term variations of biodiversity are significant signs of environmental change. Concerning the Mediterranean sea, data are available to compare possible variations in the species richness and faunal compositions, which are responsible of loss or turn-over of biodiversity18,19,26. Moreover, enclosed saline coastal basins, such as the case of the Faro Lake, represent good models of aquatic system to study temporal variation of sponge biodiversity26.

Firstly, we identified seven sponges, complementing the traditional identification by morphological features using a molecular approach, based on DNA sequencing of 28S and 18S rDNA, ITS and CO1. Our results demonstrated that none of the molecular markers alone was able to define the sponges under analysis up to the lowest taxonomic level. Indeed, molecular markers were found to be suitable depending on the species of sponge to be classified. However, it must be considered that the barcoding analysis could be negatively affected by the lack of curated sequences collection.

Among these used molecular markers, 28S and 18S rRNA are characterized by sufficiently heterogeneous regions useful to address phylogeny at different levels27,28. Because of their rapid evolution, ITS regions are considered markers at high resolution29. The COI mitochondrial DNA locus, despite the high variability at the sequence level, it is easy to amplify for its conservation across multicellular animals and abundant in eukaryotic DNA30,31. In fact, it resulted to be the most successful molecular marker to discriminate sponges at various taxonomic levels32,33. According to these literature data, no single marker exists for all sponge species, having each marker its strength and limitations34. This difficulty is also linked to the incomplete sequences annotated in database, so limiting phylogeny-based molecular taxonomic approaches that are commonly used for species identification. For this reason, a multi-locus-based molecular approach is recommended for the reliability in the case of sponge identification34. This was in complete agreement with our experimental strategy for the identification of sponges under analysis.

An important finding achieved by this study regarded the fact that, among the three sponges collected at Faro Lake, only E. discophorus was recorded in 2013 during a survey on the long-term taxonomic composition and distribution of the shallow-water sponge fauna from this meromictic–anchialine coastal basin26. The other two species, O. cf. perforata and S. spinosulus, were not reported so far, suggesting them to be new colonizers of this lake. Recently, the significant number of first reports of species from several biogeographic regions found in the Faro Lake35,36,37,38 is probably related to the import of bivalves from Atlantic and Mediterranean sites, for aquaculture activities. All three sponges usually live on rocks, coralligenous concretions and marine caves in the Mediterranean. In addition, O. cf. perforata is a rare species in the Mediterranean. Concerning the other sponges collected in the Gulf of Naples, T. aurantium, A. damicornis, A. acuta and A. oroides, represent typical species for the Mediterranean, as well as, G. cydonium.

Furthermore, through metataxonomic analysis, we also investigated the bacterial diversity among these Mediterranean sites. Recent advances in molecular ecology techniques, such as the sequencing of bacterial 16S rRNA gene, led to a clear picture of the taxonomic and functional composition of marine microbiota, including associated symbionts39.

Our results showed that sponges under analysis host diverse bacterial communities. Surprisingly, sponges collected in the Faro Lake were characterized by a more diversified composition of phyla in comparison to those collected in the Gulf of Naples (Fig. 4; Figure S9). Moreover, G. cydonium revealed a little sequencing depth (Fig. 1), probably related to the uniqueness of the collecting site (Table 1), which has strictly influenced the symbiotic community by selecting a few species of well adapted bacteria. In fact, Secca delle Fumose represents a good case study, due to the variations in seawater pH and gas-rich hydrothermal vents40. As reported in literature, extreme environments are well-known to inhabit a macro- and micro-biota with high biotechnological value41,42,43,44.

Moreover, PCA analysis suggested interesting results for the sponges collected from Punta San Pancrazio (Ischia Island). In fact, A. oroides revealed considerable similarities to the sponges retrieved in the Strait of Messina, since they clustered in the same group (Fig. 2). On the other hand, A. acuta separated from the other sponges under analysis, revealing a completely different symbiotic community that needs to be taken into consideration (Fig. 2).

The phylogeny of sponges must also be considered in our analysis, because it probably influenced the community structure. In fact, S. spinosolus, A. oroides, E. discophorus belonging to Dictyoceratida, Agelasida, Tetractinellida orders, respectively, were recorded as High Microbial Abundance (HMA) species, while T. aurantium, A. damicornis and A. acuta were instead indicated as Low Microbial Abundance (LMA) species45,46,47. HMA sponges hosted a more diversified symbiont community than LMA, which were discovered to be extremely stable over seasonal and inter-annual scales46. The correlation of sponge taxonomy to the abundance and diversification of microbial communities was evident in the heat-map, since the HMA species displayed higher values of bacterial features (Fig. 3). Moreover, these considerations could justify the clustering obtained through the PCA analysis, where T. aurantium and A. damicornis separated from S. spinosolus, A. oroides and E. discophorus (Fig. 2).

Many studies reported about the sponge associated-bacteria as good candidates for the isolation of natural compounds, useful in biotechnological applications. This study represents a first evaluation of the biotechnological potential of the aforementioned sponges. For this reason, we will further discuss the known bioactivities of the most abundant bacterial phyla identified in the considered sponges, according to the available literature.

The symbiotic community of the five sponges from the Gulf of Naples, mainly in T. aurantium, A. damicornis, A. acuta, A. oroides and G. cydonium was dominated by Proteobacteria, classes Alphaproteobacteria, Deltaproteobacteria and Gammaproteobateria (Figs. 3, 4; Figure S9).

Alphaproteobacteria were commonly found in the Mediterranean, mainly in the sponges Sarcotragus fasciculatus, Ircinia oros and Ircinia strobilina48,49. Overall, proteobacteria are known to produce N-acyl homoserine lactone (AHL) signal molecules involved in bacterial quorum sensing50. In fact, several species belonging to Alpha- and Gamma-proteobacteria, isolated from the Mediterranean sponges Halichondria panicea, Ircinia fasciculata, Axinella polypoides, and Acanthella sp.51 and from the Red sea sponge Suberea mollis52 showed antimicrobial activities, making them suitable tools for pharmacological purposes53,54,55,56,57.

The phylum Actinobacteria (class Acidimicrobiia) was the most abundant in S. spinosulus and E. discophorus (Figs. 3, 4; Figure S9), also found in T. aurantium and A. acuta. Actinobacteria are Gram positive, mostly aerobic, mycelial and primarily soil organisms, but recent studies revealed that some Actinobacteria taxa were also well-adapted to marine environments. Moreover, these bacteria were attracting interest as key producers of therapeutics, for their great potential in extracellular enzyme production, as well as in the synthesis of a variety of bioactive metabolites with antimicrobial and antifungal activity11,58,59. In fact, Actinobacteria together with the already discussed Proteobacteria, showed antagonistic activity against bacterial belonging to the genera Bacillus, Pseudovibrio, Ruegeria, Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli K12, and fungi Fusarium sp. P25, Trypanosoma brucei TC 221, Leishmania major, Aspergillus fumigatus, Candida glabrata and C. albicans13,52,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71. Furthermore, this group of bacteria, also isolated from Suberites domuncula and Dysidea sp., showed antimicrobial, antifungal and cytotoxic activity against different cell lines as HeLa cells and pheochromocytoma (PC12) cells53,54,55,56.

Dehalococcoides and Anaerolineae (a class of the phylum Chloroflexi) seem to be peculiar species of both collection sites, being detected in S. spinolosus, E. discophorous, and A. oroides (Figs. 3, 4; Figure S9). This was an interesting finding, because both bacterial groups were isolated for the first time from Mediterranean sponges. In fact, Anaerolineae were found most abundant in Aaptos suberitoides and Xestospongia testudinaria collected in South East Misool, Raja Ampat, West Papua (Indonesia)72,73. No data were reported so far for marine biotechnology applications. In contrast, the anaerobic Dehalococcoides showed surprising capabilities to transform various chlorinated organic compounds via reductive dechlorination. For this reason, Dehalococcoides were extensively used for the restoration of environments contaminated by chlorinated organics, which are normally released through industrial and agricultural activities74,75. ASVs analysis showed a peculiar abundance of the phylum Verrucomicrobia (class Verrucomicrobiae) in the sponge O. cf. perforata (Figs. 3, 4; Figure S9). Little information was reported on the abundance and ecology of aquatic Verrucomicrobia, being prevalent in lakes characterized by nutrient abundance and phosphorus availability76,77. These bacteria play an important role in global carbon cycling, processing decaying organic materials and degrading various polysaccharides78,79,80,81. It was found that the sponge-symbiotic Verrucomicrobiae bacteria (e.g. Petrosia ficiformis) exhibited enrichment of the toxin-antitoxin (TA) system suggesting the hypothesis that these bacteria use these systems as a defense mechanism against antimicrobial activity deriving from the abundant microbial community co-inhabiting their host77. Rubritalea squalenifaciens (strain HOact23T; MBIC08254T) is a rare marine bacterium belonging to the phylum Verrucomicrobia, isolated from Halichondria okadai (collected in Japan), from which a novel acyl glyco-carotenoic acids, diapolycopenedioic acid xylosyl esters A, B, and C, were isolated as red pigments with a potent antioxidative activity82.

Furthermore, Nitrospirae (class Nitrospira) was the most abundant bacterial phylum in the three sponges from the Gulf of Naples, A. damicornis, G. cydonium and A. acuta, as well as, in O. cf. perforata and E. discophous from the Faro Lake (Figs. 3, 4; Figure S9). The first described Nitrospira species was N. marina, isolated by Watson et al.83 from water collected in the Gulf of Maine. In particular, Nitrospira spp. play pivotal roles in nitrification as anaerobic chemolithoautotrophic nitrite-oxidizing bacterium84. These bacteria also have been found in several sponge species such as Theonella swinhoei and Geodia barretti85,86. Concerning their biotechnological potential, very little information is available so far. A recent work, using BLASTp search against the Integrated Microbial Genomes (IMG) database, identified a Pseudoalteromonas luteoviolacea gene encoding for a L-amino acid oxidase (LAAO) with antimicrobial properties in a strain belonging to the phylum Nitrospinae87.

Summarizing, our data pointed out the attention on the species biodiversity of the Mediterranean Sea and on 16S rRNA sequence datasets, which allowed to the detection of several signature resident microbial fauna. In addition, data reported on the biotechnological potential of the bacteria identified in the eight sponges under analysis, suggest the need for further validations through bioassay-guided fractionation to identify novel metabolites useful for the pharmaceutical, cosmeceutical and nutraceutical fields.

Methods

Sponge collection

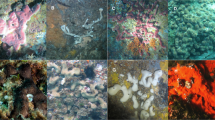

The size of sponge samples ranged from 10 to 20 cm in diameter. Three sponge samples, O.per, S.spi and E.dis were collected at Faro Lake (Messina, Sicily; depth = 2–3 m; 38°16’N, 15°38’E, Fig. 5A; temperature 20 °C, pH 8.25, salinity 31 PSU) in October 2019.

The site Faro Lake (0.263 Km2) is the deepest coastal lake in Italy located within the Natural Reserve of “Capo Peloro” (NE Sicily). The Faro Lake is characterized by a funnel-shape profile, with a steep sloping bottom reaching the maximum depth of 29 m in the central area and a wide nearshore shallow waters area. In the deepest part, the Faro Lake shows typical features of a meromictic temperate basin, with an oxygenated mixolimnion (the upper 15 m) and a lower anoxic and sulphidic monimolimnion88. Two channels, a northern and a north-eastern, connect the lake to the Tyrrhenian Sea and the Strait of Messina. Salinity ranges are from 26 to 36 PSU, temperature from 10 to 30 °C and pH ranges from 7.0–8.626. Four samples were collected in the Gulf of Naples in September 2019 by scuba diving of Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn of Naples (temperature 23.9 °C, pH 8.3, salinity 38 PSU): two samples, reported as T.aur and A.dam, were collected at Porto Paone (depth = 15–17 m; 40°47ʹN, 14°9ʹE, Fig. 5B); A.acu and A.oro were retrieved from Punta San Pancrazio (depth = 7–9 m; 40°42ʹN, 13°57ʹE, Fig. 5C); G.cyd (Geodia cydonium) was harvested at Secca delle Fumose, Parco Sommerso di Baia (depth = 20 m; 40°49ʹN, 14°5ʹE, Fig. 5D). All collecting sites were selected on the basis of some data reporting on the great biodiversity and, in some cases, the presence of alien species26,89,90.

Collected samples were immediately washed at least three times with filter-sterilized natural seawater. A fragment of each specimen was preserved in 70% ethanol for taxonomic identification; another fragment was then placed into individual sterile tubes and kept in RNAlater© at − 20 °C used for molecular analysis. Details on sampling were reported in Table 1.

Morphological analysis of the sponges

For the taxonomic analysis, the spicules of each sponge specimen, spicule complement and skeletal architecture, were examined under light microscopy following published protocols91,92. Taxonomic decisions were made according to the classification present in the World Porifera Database (WPD)14. The sponge samples were all identified at the species level.

DNA extraction and PCR amplification

About 10 mg of tissue was used for DNA extraction by QIAamp® DNA Micro kit (QIAGEN), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA quantity (ng/μL) was evaluated by a NanoDrop spectrophotometer. PCR reactions were performed on the C1000 Touch Thermal Cycler (BioRad) in a 30 µL reaction mixture final volume including about 50–100 ng of genomic DNA, 6 µL of 5X Buffer GL (GeneSpin Srl, Milan, Italy), 3 µL of dNTPs (2 mM each), 2 µL of each forward and reverse primer (25 pmol/µL), 0.2 µL of Xtra Taq Polymerase (5 U/µL, GeneSpin Srl, Milan, Italy) as follows (for primer sequences, see also Table S13):

-

i.

for 18S and 28S, a denaturation step at 95 °C for 2 min, 35 cycles denaturation step at 95 °C for 1 min, annealing step at 60 °C (A/B93,94), 57 °C (C2/D295), 55 °C (18S-AF/18S-BR, NL4F/NL4R96,97), 52 °C (18S1/18S298) for 1 min and 72 °C of primer extension for 2 min, a final extension step at 72 °C for 10 min;

-

ii.

ITS primers (RA2/ITS2.294,99), a first denaturation at 95 °C for 2 min, 35 cycles denaturation step at 95 °C for 1 min, annealing step at 67 °C for 1 min and 72 °C of primer extension for 2 min, a final extension step at 72 °C for 10 min;

-

iii.

CO1 primers (dgLCO1490/dgHCO2198100), a first denaturation at 94 °C for 3 min, 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 45 °C for 30 s and primer extension at 72 °C for 1 min.

PCR products were separated on 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis in TAE buffer (40 mM Tris–acetate, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) using a 100 bp DNA ladder (GeneSpin Srl, Milan, Italy) and purified by QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. PCR amplicons were then sequenced in both strands through Applied Biosystems (Life Technologies) 3730 Analyzer (48 capillaries). Sequences produced were ~ 650 bases long in average with more than 97.5% accuracy, starting from PCR fragments. Each 18S, 28S and CO1 PCR products were aligned to GenBank using Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) and then aligned with highly similar sequence using MultiAlin (http://multalin.toulouse.inra.fr/multalin/, see Figures S1-S7).

Metagenomic DNA extraction, Illumina MiSeq sequencing and diversity analysis

About 250 mg of tissue were weighted and used for DNA extraction by using DNeasy® PowerSoil® Pro Kit (QIAGEN), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA quantity (ng/μL) and quality (A260/280, A260/230) were evaluated by a NanoDrop spectrophotometer. DNA samples were separated by 0.8% agarose gel electrophoresis in TAE buffer (40 mM Tris–acetate, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0) to check DNA integrity. 30 ng/μL (final concentration) of sample was used for metataxonomic analysis performed by Bio-Fab Research (Roma, Italy). Illumina adapter overhang nucleotide sequences were added to the gene‐specific primer pairs targeting the V3-V4 region (S-D-Bact-0341-b-S-17/S-D-Bact-0785-a-A-2), with the following sequences:

Forward = 5' TCGTCGGCAGCGTCAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGCCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG-3',

Reverse = 5'-GTCTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGGACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC-3′101.

For 16S PCR amplification, 2.5 µL of microbial genomic DNA (5 ng/µL in 10 mM Tris pH 8.5), 5 µL of each Forward and Reverse primer and 12.5 µL of 2 × KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix to a final volume of 25 µL were used. Thermocycler conditions were set as follows: initial denaturation at 95 °C for 3 min, 25 cycles of 95 °C (30 s), 55 °C (30 s), 72 °C (30 s), final extension at 72 °C for 5 min, hold at 4 °C.

After 16S amplification, a PCR clean-up was done to purify the V3-V4 amplicon from free primers and primer dimer species. This step was followed by another limited‐cycle amplification step to add multiplexing indices and Illumina sequencing adapters by using a Nextera XT Index Kit. A second step of clean-up was further performed and then libraries were normalized and pooled by denoising processes (Table S14), and sequenced on Illumina MiSeq Platform with 2 × 300 bp paired-end reads. Taxonomy was assigned using "home made" Naive Bayesian Classifier trained on V3-V4 16S sequences of SILVA 132 database102. Frequencies per feature and per sample are shown in Figures S10-S11.

QIIME 2 (Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology) platform103 was used for microbiome analysis from raw DNA sequencing data. QIIME 2 analysis workflow was performed by demultiplexing, quality filtering, chimera removal, taxonomic assignment, and diversity analyses (alpha and beta).

Taxonomy BarPlot (Figure S9) was generated through a R version 4.1.1104 using Cairo graphics library105.

Species diversity was estimated by i. Chao 1 index106, which is qualitative species-based method; ii. Shannon107,108 and iii. Simpson109 indices, which are quantitative species-based measures. All these indices were estimated at three taxa levels (Level 5 = Family, Level 6 = Genus, Level 7 = Species). For alpha and beta diversity, significant differences were assessed by Kruskal–Wallis test and pairwise PERMANOVA analysis, respectively. Moreover, Bray–Curtis and “un-, weighted” UniFrac metrics were used to calculate a distance matrix between each pair of samples, independently from the environmental variables.

Data availability

The full dataset of raw data was deposited in the SRA database (Submission ID: SUB8692761; BioProject ID: PRJNA683751).

References

Joseph, B. & Sujatha, S. Pharmacologically important natural products from marine sponges. J. Nat. Prod. 4, 5–12 (2011).

Bergmann, W. & Feeney, R. J. Contributions to the study of marine products XXXII The nucleosides of sponges. I. J. Org. Chem. 16, 981–987 (1951).

Munro, M. H. G., Luibrand, R. T. & Blunt, J. W. The search for antiviral and anticancer compounds from marine organisms. in Bioorganic Marine Chemistry (ed. Scheuer, P. J.) vol. 1 93–176 (Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg, 1987).

Fuerst, J. A. Diversity and biotechnological potential of microorganisms associated with marine sponges. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 98, 7331–7347 (2014).

Mehbub, M. F., Lei, J., Franco, C. & Zhang, W. Marine sponge derived natural products between 2001 and 2010: Trends and opportunities for discovery of bioactives. Mar. Drugs 12, 4539–4577 (2014).

Piel, J. Metabolites from symbiotic bacteria. Nat. Prod. Rep. 26, 338–362 (2009).

Piel, J. et al. Antitumor polyketide biosynthesis by an uncultivated bacterial symbiont of the marine sponge Theonella swinhoei. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101, 16222–16227 (2004).

Noro, J. C., Kalaitzis, J. A. & Neilan, B. A. Bioactive natural products from Papua New Guinea marine sponges. Chem. Biodivers. 9, 2077–2095 (2012).

Schirmer, A. et al. Metagenomic analysis reveals diverse polyketide synthase gene clusters in microorganisms associated with the marine sponge Discodermia dissoluta. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 4840–4849 (2005).

Siegl, A. & Hentschel, U. PKS and NRPS gene clusters from microbial symbiont cells of marine sponges by whole genome amplification. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2, 507–513 (2010).

Graça, A. P. et al. Antimicrobial activity of heterotrophic bacterial communities from the marine sponge Erylus discophorus (Astrophorida, Geodiidae). PLoS ONE 8, e78992 (2013).

Santos, O. C. S. et al. Investigation of biotechnological potential of sponge-associated bacteria collected in Brazilian coast. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 60, 140–147 (2015).

Su, P., Wang, D. X., Ding, S. X. & Zhao, J. Isolation and diversity of natural product biosynthetic genes of cultivable bacteria associated with marine sponge Mycale sp from the coast of Fujian. China. Can. J. Microbiol. 60, 217–225 (2014).

Van Soest, R. W. M. et al. World Porifera Database. http://www.marinespecies.org/porifera/. (2020).

Bertolino, M. et al. Stability of the sponge assemblage of Mediterranean coralligenous concretions along a millennial time span. Mar. Ecol. 35, 149–158 (2014).

Longo, C. et al. Sponges associated with coralligenous formations along the Apulian coasts. Mar. Biodivers. 48, 2151–2163 (2018).

Costa, G. et al. Sponge community variation along the Apulian coasts (Otranto Strait) over a pluri-decennial time span Does water warming drive a sponge diversity increasing in the Mediterranean Sea?. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. United Kingdom 99, 1519–1534 (2019).

Bertolino, M. et al. Changes and stability of a Mediterranean hard bottom benthic community over 25 years. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. United Kingdom 96, 341–350 (2016).

Bertolino, M. et al. Have climate changes driven the diversity of a Mediterranean coralligenous sponge assemblage on a millennial timescale?. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 487, 355–363 (2017).

Gerovasileiou, V. et al. New Mediterranean biodiversity records. Mediterr. Mar. Sci. 18, 355–384 (2017).

Ulman, A. et al. A massive update of non-indigenous species records in Mediterranean marinas. PeerJ 2017, e3954 (2017).

Costantini, M. An analysis of sponge genomes. Gene 342, 321–325 (2004).

Costantini, S. et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of a methanol extract from the marine sponge Geodia cydonium on the human breast cancer MCF-7 cell line. Mediators Inflamm. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/204975 (2015).

Costantini, S. et al. Evaluating the effects of an organic extract from the mediterranean sponge Geodia cydonium on human breast cancer cell lines. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18, 2112 (2017).

Coll, M. et al. The biodiversity of the Mediterranean Sea: estimates, patterns, and threats. PLoS ONE 5, e11842 (2010).

Marra, M. V. et al. Long-term turnover of the sponge fauna in Faro Lake (North-East Sicily, Mediterranean Sea). Ital. J. Zool. 83, 579–588 (2016).

Cárdenas, P., Xavier, J. R., Reveillaud, J., Schander, C. & Rapp, H. T. Molecular phylogeny of the astrophorida (Porifera, Demospongiaep) reveals an unexpected high level of spicule homoplasy. PLoS ONE 6, e18318 (2011).

Erpenbeck, D. et al. The phylogeny of halichondrid demosponges: past and present re-visited with DNA-barcoding data. Org. Divers. Evol. 12, 57–70 (2012).

Abdul Wahab, M. A., Fromont, J., Whalan, S., Webster, N. & Andreakis, N. Combining morphometrics with molecular taxonomy: How different are similar foliose keratose sponges from the Australian tropics?. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 73, 23–39 (2014).

Wörheide, G. Low variation in partial cytochrome oxidase subunit I (COI) mitochondrial sequences in the coralline demosponge Astrosclera willeyana across the Indo-Pacific. Mar. Biol. 148, 907–912 (2006).

Carella, M., Agell, G., Cárdenas, P. & Uriz, M. J. Phylogenetic reassessment of antarctic tetillidae (Demospongiae, Tetractinellida) reveals new genera and genetic similarity among morphologically distinct species. PLoS ONE 11, 1–33 (2016).

Morrow, C. C. et al. Congruence between nuclear and mitochondrial genes in Demospongiae: a new hypothesis for relationships within the G4 clade (Porifera: Demospongiae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 62, 174–190 (2012).

Vargas, S. et al. Diversity in a cold hot-spot: DNA-barcoding reveals patterns of evolution among Antarctic demosponges (class demospongiae, phylum Porifera). PLoS ONE 10, 1–17 (2015).

Yang, Q., Franco, C. M. M., Sorokin, S. J. & Zhang, W. Development of a multilocus-based approach for sponge (phylum Porifera) identification: refinement and limitations. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–14 (2017).

Cosentino, A., Giacobbe, S. & Potoschi, A. The CSI of Faro coastal lake (Messina): a natural observatory for the incoming of marine alien species. Biol. Mar. Mediterr. 16, 132–133 (2009).

Zagami, G., Costanzo, G. & Crescenti, N. First record in Mediterranean Sea and redescription of the bentho-planktonic calanoid copepod species Pseudocyclops xiphophorus Wells, 1967. J. Mar. Syst. 55, 67–76 (2005).

Zagami, G. et al. Biogeographical distribution and ecology of the planktonic copepod Oithona davisae: rapid invasion in lakes Faro and Ganzirri (central Meditteranean Sea). in Trends in copepod studies. Distribution, biology and ecology (ed. Uttieri, M.) 1–55 (Nova Science Publishers, 2017).

Saccà, A. & Giuffrè, G. Biogeography and ecology of Rhizodomus tagatzi, a presumptive invasive tintinnid ciliate. J. Plankton Res. 35, 894–906 (2013).

Cao, S. et al. Structure and function of the Arctic and Antarctic marine microbiota as revealed by metagenomics. Microbiome 8, 47 (2020).

Donnarumma, L. et al. Environmental and benthic community patterns of the shallow hydrothermal area of Secca Delle Fumose (Baia, Naples, Italy). Front. Mar. Sci. 6, 1–15 (2019).

Poli, A., Anzelmo, G. & Nicolaus, B. Bacterial exopolysaccharides from extreme marine habitats: production, characterization and biological activities. Mar. Drugs 8, 1779–1802 (2010).

Shukla, P. J., Nathani, N. M. & Dave, B. P. Marine bacterial exopolysaccharides [EPSs] from extreme environments and their biotechnological applications. Int. J. Res. Biosci. 6, 20–32 (2017).

Patel, A., Matsakas, L., Rova, U. & Christakopoulos, P. A perspective on biotechnological applications of thermophilic microalgae and cyanobacteria. Bioresour. Technol. 278, 424–434 (2019).

Schultz, J. & Rosado, A. S. Extreme environments: a source of biosurfactants for biotechnological applications. Extremophiles 24, 189–206 (2020).

Gloeckner, V. et al. The HMA-LMA dichotomy revisited: An electron microscopical survey of 56 sponge species. Biol. Bull. 227, 78–88 (2014).

Erwin, P. M., Coma, R., López-Sendino, P., Serrano, E. & Ribes, M. Stable symbionts across the HMA-LMA dichotomy: Low seasonal and interannual variation in sponge-associated bacteria from taxonomically diverse hosts. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 91, 1–11 (2015).

Moitinho-Silva, L. et al. The sponge microbiome project. Gigascience 6, 1–13 (2017).

Hardoim, C. C. P. & Costa, R. Temporal dynamics of prokaryotic communities in the marine sponge Sarcotragus spinosulus. Mol. Ecol. 23, 3097–3112 (2014).

Karimi, E. et al. Metagenomic binning reveals versatile nutrient cycling and distinct adaptive features in alphaproteobacterial symbionts of marine sponges. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 94, 1–18 (2018).

Mohamed, N. M. et al. Diversity and quorum-sensing signal production of Proteobacteria associated with marine sponges. Environ. Microbiol. 10, 75–86 (2008).

Thiel, V. & Imhoff, J. F. Phylogenetic identification of bacteria with antimicrobial activities isolated from Mediterranean sponges. Biomol. Eng. 20, 421–423 (2003).

Bibi, F., Yasir, M., Al-Sofyani, A., Naseer, M. I. & Azhar, E. I. Antimicrobial activity of bacteria from marine sponge Suberea mollis and bioactive metabolites of Vibrio sp EA348. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 27, 1139–1147 (2020).

Thakur, A. N. et al. Antiangiogenic, antimicrobial, and cytotoxic potential of sponge-associated bacteria. Mar. Biotechnol. 7, 245–252 (2005).

Taylor, M. W., Radax, R., Steger, D. & Wagner, M. Sponge-associated microorganisms: Evolution, ecology, and biotechnological potential. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 71, 295–347 (2007).

Thomas, T. R. A., Kavlekar, D. P. & LokaBharathi, P. A. Marine drugs from sponge-microbe association—A review. Mar. Drugs 8, 1417–1468 (2010).

Brinkmann, C. M., Marker, A. & Kurtböke, D. I. An overview on marine sponge-symbiotic bacteria as unexhausted sources for natural product discovery. Diversity 9, 40 (2017).

Haber, M. & Ilan, M. Diversity and antibacterial activity of bacteria cultured from Mediterranean Axinella spp sponges. J. Appl. Microbiol. 116, 519–532 (2014).

Öner, Ö. et al. Cultivable sponge-associated Actinobacteria from coastal area of eastern Mediterranean Sea. Adv. Microbiol. 04, 306–316 (2014).

Gonçalves, A. C. S. et al. Draft genome sequence of Vibrio sp strain Vb278, an antagonistic bacterium isolated from the marine sponge Sarcotragus spinosulus. Genome Announc. 3, 2014–2015 (2015).

Cheng, C. et al. Biodiversity, anti-trypanosomal activity screening, and metabolomic profiling of actinomycetes isolated from Mediterranean sponges. PLoS ONE 10, 1–21 (2015).

Graça, A. P. et al. The antimicrobial activity of heterotrophic bacteria isolated from the marine sponge Erylus deficiens (Astrophorida, Geodiidae). Front. Microbiol. 6, 389 (2015).

Kuo, J. et al. Antimicrobial activity and diversity of bacteria associated with Taiwanese marine sponge Theonella swinhoei. Ann. Microbiol. 69, 253–265 (2019).

Liu, T. et al. Diversity and antimicrobial potential of Actinobacteria isolated from diverse marine sponges along the Beibu Gulf of the South China Sea. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 95, 1–10 (2019).

Hentschel, U. et al. Isolation and phylogenetic analysis of bacteria with antimicrobial activities from the Mediterranean sponges Aplysina aerophoba and Aplysina cavernicola. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 35, 305–312 (2001).

Chelossi, E., Milanese, M., Milano, A., Pronzato, R. & Riccardi, G. Characterisation and antimicrobial activity of epibiotic bacteria from Petrosia ficiformis (Porifera, Demospongiae). J. Exp. Mar. Bio. Ecol. 309, 21–33 (2004).

Kennedy, J. et al. Isolation and analysis of bacteria with antimicrobial activities from the marine sponge Haliclona simulans collected from irish waters. Mar. Biotechnol. 11, 384–396 (2009).

Penesyan, A., Marshall-Jones, Z., Holmstrom, C., Kjelleberg, S. & Egan, S. Antimicrobial activity observed among cultured marine epiphytic bacteria reflects their potential as a source of new drugs. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 69, 113–124 (2009).

Santos, O. C. S. et al. Isolation, characterization and phylogeny of sponge-associated bacteria with antimicrobial activities from Brazil. Res. Microbiol. 161, 604–612 (2010).

Flemer, B. et al. Diversity and antimicrobial activities of microbes from two Irish marine sponges, Suberites carnosus and Leucosolenia sp. J. Appl. Microbiol. 112, 289–301 (2012).

Margassery, L. M., Kennedy, J., O’Gara, F., Dobson, A. D. & Morrissey, J. P. Diversity and antibacterial activity of bacteria isolated from the coastal marine sponges Amphilectus fucorum and Eurypon major. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 55, 2–8 (2012).

Abdelmohsen, U. R. et al. Actinomycetes from Red Sea sponges: sources for chemical and phylogenetic diversity. Mar. Drugs 12, 2771–2789 (2014).

Montalvo, N. F. & Hill, R. T. Sponge-associated bacteria are strictly maintained in two closely related but geographically distant sponge hosts. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 7207–7216 (2011).

Cleary, D. F. R. et al. Compositional analysis of bacterial communities in seawater, sediment, and sponges in the Misool coral reef system. Indonesia. Mar. Biodivers. 48, 1889–1901 (2018).

Bedard, D. L., Ritalahti, K. M. & Löffler, F. E. The Dehalococcoides population in sediment-free mixed cultures metabolically dechlorinates the commercial polychlorinated biphenyl mixture aroclor 1260. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 2513–2521 (2007).

Taş, N., Van Eekert, M. H. A., De Vos, W. M. & Smidt, H. The little bacteria that can - Diversity, genomics and ecophysiology of ‘Dehalococcoides’ spp in contaminated environments. Microb. Biotechnol. 3, 389–402 (2010).

Arnds, J., Knittel, K., Buck, U., Winkel, M. & Amann, R. Development of a 16S rRNA-targeted probe set for Verrucomicrobia and its application for fluorescence in situ hybridization in a humic lake. Syst. Appl. Microbiol. 33, 139–148 (2010).

Sizikov, S. et al. Characterization of sponge-associated Verrucomicrobia: microcompartment-based sugar utilization and enhanced toxin–antitoxin modules as features of host-associated Opitutales. Environ. Microbiol. 22, 4669–4688 (2020).

Cardman, Z. et al. Verrucomicrobia are candidates for polysaccharide-degrading bacterioplankton in an Arctic fjord of Svalbard. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80, 3749–3756 (2014).

Cabello-Yeves, P. J. et al. Reconstruction of diverse verrucomicrobial genomes from metagenome datasets of freshwater reservoirs. Front. Microbiol. 8, 2131 (2017).

He, S. et al. Ecophysiology of freshwater Verrucomicrobia inferred from metagenome-assembled genomes. MSphere 2, e00277 (2017).

Sichert, A. et al. Verrucomicrobia use hundreds of enzymes to digest the algal polysaccharide fucoidan. Nat. Microbiol. 5, 1026–1039 (2020).

Shindo, K. et al. Diapolycopenedioic acid xylosyl esters A, B, and C, novel antioxidative glyco-C30-carotenoic acids produced by a new marine bacterium Rubritalea Squalenifaciens. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 61, 185–191 (2008).

Watson, S. W., Bock, E., Valois, F. W., Waterbury, J. B. & Schlosser, U. Nitrospira marina gen. nov sp nov: a chemolithotrophic nitrite-oxidizing bacterium. Arch. Microbiol. 144, 1–7 (1986).

Daims, H. & Wagner, M. Nitrospira. Trends Microbiol. 26, 462–463 (2018).

Off, S., Alawi, M. & Spieck, E. Enrichment and physiological characterization of a novel nitrospira-like bacterium obtained from a marine sponge. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76, 4640–4646 (2010).

Feng, G., Sun, W., Zhang, F., Karthik, L. & Li, Z. Inhabitancy of active Nitrosopumilus-like ammonia-oxidizing archaea and Nitrospira nitrite-oxidizing bacteria in the sponge Theonella swinhoei. Sci. Rep. 6, 1–11 (2016).

Andreo-Vidal, A., Sanchez-Amat, A. & Campillo-Brocal, J. C. The Pseudoalteromonas luteoviolacea L-amino acid oxidase with antimicrobial activity is a flavoenzyme. Mar. Drugs 16, 499 (2018).

Saccà, A., Guglielmo, L. & Bruni, V. Vertical and temporal microbial community patterns in a meromictic coastal lake influenced by the Straits of Messina upwelling system. Hydrobiologia 600, 89–104 (2008).

Polese, G. et al. Meiofaunal assemblages of the bay of Nisida and the environmental status of the Phlegraean area (Naples, Southern Italy). Mar. Biodivers. 48, 127–137 (2018).

Gambi, M. C., Tiberti, L. & Mannino, A. M. An update of marine alien species off the Ischia Island (Tyrrhenian Sea) with a closer look at neglected invasions of Lophocladia lallemandii (Rhodophyta). Not. Sibm 75, 58–65 (2019).

Hooper, J. N. A. ‘Sponguide’. Guide to sponge collection and identification. https://www.academia.edu/34258606/SPONGE_GUIDE_GUIDE_TO_SPONGE_COLLECTION_AND_IDENTIFICATION_Version_August_2000. (2000).

Rützler, K. Sponges in coral reefs. in Coral reefs: Research methods, monographs on oceanographic methodology (eds. Stoddart, D. R. & Johannes, R. E.) 299–313 (Paris: Unesco, 1978).

Medlin, L., Elwood, H. J., Stickel, S. & Sogin, M. L. The characterization of enzymatically amplified eukaryotic 16S-like rRNA-coding regions. Gene 71, 491–499 (1988).

Schmitt, S., Hentschel, U., Zea, S., Dandekar, T. & Wolf, M. ITS-2 and 18S rRNA gene phylogeny of Aplysinidae (Verongida, Demospongiae). J. Mol. Evol. 60, 327–336 (2005).

Chombard, C., Boury-Esnault, N. & Tillier, S. Reassessment of homology of morphological characters in Tetractinellid sponges based on molecular data. Syst. Biol. 47, 351–366 (1998).

Collins, A. G. Phylogeny of medusozoa and the evolution of cnidarian life cycles. J. Evol. Biol. 15, 418–432 (2002).

Dohrmann, M., Janussen, D., Reitner, J., Collins, A. G. & Wörheide, G. Phylogeny and evolution of glass sponges (Porifera, Hexactinellida). Syst. Biol. 57, 388–405 (2008).

Manuel, M. et al. Phylogeny and evolution of calcareous sponges: monophyly of calcinea and calcaronea, high level of morphological homoplasy, and the primitive nature of axial symmetry. Syst. Biol. 52, 311–333 (2003).

Wörheide, G., Degnan, B., Hooper, J. & Reitner, J. Phylogeography and taxonomy of the Indo-Pacific reef cave dwelling coralline demosponge Astrosclera willeyana: new data from nuclear internal transcribed spacer sequences. Proc. 9th Int. Coral Reef Symp. 1, 339–346 (2002).

Meyer, C. P., Geller, J. B. & Paulay, G. Fine scale endemism on coral reefs: Archipelagic differentiation in turbinid gastropods. Evolution 59, 113–125 (2005).

Klindworth, A. et al. Evaluation of general 16S ribosomal RNA gene PCR primers for classical and next-generation sequencing-based diversity studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, e1 (2013).

Quast, C. et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: Improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, 590–596 (2013).

Bolyen, E. et al. Reproducible, interactive, scalable and extensible microbiome data science using QIIME 2. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 852–857 (2019).

R Core Team. A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for statistical computing, Vienna, Austria. (2020).

Urbanek, S. & Horner, J. Cairo: R Graphics device using Cairo graphics library for creating high-quality bitmap (PNG, JPEG, TIFF), vector (PDF, SVG, PostScript) and display (X11 and Win32) output. R package version 1.5–12.2. https://cran.r-project.org/package=Cairo (2020).

Chao, B. F. Interannual length-of-the-day variation with relation to the southern oscillation/El Nino. Geophys. Res. Lett. 11, 541–544 (1984).

Shannon, C. E. A mathematical theory of communication. Bell Syst. Tech. J. 27(379–423), 623–656 (1948).

Shannon, C. E. & Weaver, W. The Mathematical Theory of Communication (University of Illinois Press, 1949).

Simpson, E. H. Measurment of diversity. Nature 163, 688 (1949).

Acknowledgements

We thank the “Parco Sommerso di Baia” in Naples for providing Geodia cydonium and the Fishing Service of Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn for its collection. We also thank Davide Caramiello from the Marine Organisms Core Facility of the Stazione Zoologica for his technical support in sponge maintenance.

Funding

Nadia Ruocco was supported by a research grant “Antitumor Drugs and Vaccines from the Sea (ADViSE)” project (PG/2018/0494374). Roberta Esposito was supported by a PhD (PhD in Biology, University of Naples Federico II) fellowship funded by the Photosynthesis 2.0 project of the Stazione Zoologica Anton Dohrn.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.R., R.E.: molecular identification of sponges, data curation; formal analysis. G.Z., S.D.M.: collection of sponge samples and their identification. M.B.: morphological analysis of sponges. M.S., F.A.: Metataxonomic analysis. S.C., V.Z.: writing—reviewing and editing. M.C.: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Writing—original draft.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ruocco, N., Esposito, R., Zagami, G. et al. Microbial diversity in Mediterranean sponges as revealed by metataxonomic analysis. Sci Rep 11, 21151 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-00713-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-00713-9

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.