Abstract

Many plants, including fruits and vegetables, release biogenic gases containing various volatile organic compounds such as ethylene (C2H4), which is a gaseous phytohormone. Non-destructive and in-situ gas sampling technology to detect trace C2H4 released from plants in real time would be attractive for visualising the ageing, ripening, and defence reactions of plants. In this study, we developed a C2H4 detection system with a detection limit of 0.8 ppb (3σ) using laser absorption spectroscopy. The C2H4 detection system consists of a mid-infrared quantum cascade laser oscillated at 10.5 µm, a multi-pass gas cell, a mid-IR photodetector, and a gas sampling system. Using non-destructive and in-situ gas sampling, while maintaining the internal pressure of the multi-pass gas cell at low pressure, the change in trace C2H4 concentration released from apples (Malus domestica Borkh.) can be observed in real time. We succeeded in observing C2H4 concentration changes with a time resolution of 1 s, while changing the atmospheric gas and surface temperature of apples from the ‘Fuji’ cultivar. This technique allows the visualisation of detailed C2H4 dynamics in plant environmental response, which may be promising for further progress in plant physiology, agriculture, and food science.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Plants generate various phytohormones and substances in their tissues and organs at all growth stages, and their expression can change in response to infectious diseases. Ethylene (C2H4) is the lightest gaseous phytohormone. It is involved in many functions, such as leaf and flower senescence, promotion of seed germination and flowering, and softening and ripening of fruit1,2,3,4. Moreover, part of the C2H4 produced in the plant is released as a volatile organic compound (VOC). For example, ripe apples and avocados release approximately < 200 µL·kg−1 h−1 of C2H45,6,7,8. Rice releases a low concentration of approximately 10 µL·kg−1 h−1 of C2H4 upon disease infection9. It has also been reported that soya beans and wheat release 10–60 ppb of C2H4 during periods of canopy expansion and rapid growth10. The amount of C2H4 released depends on the weight and growing conditions of the plants, and the concentration of C2H4 is strongly influenced by the gas sampling method. In many cases, non-destructive and real-time detection of ppb-level C2H4 allows the visualisation of C2H4 dynamics to plant environmental responses.

Some methods to detect trace C2H4 exist, such as gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC/MS), chemiresistive sensors, and laser sensing. GC/MS is a widely used method for detecting and analysing numerous VOCs, including C2H411,12. Nevertheless, GC/MS is not suitable for real-time detection of gas concentration changes, owing to the necessity of long measurement times and complex pretreatments. However, chemiresistive sensors made from single-walled carbon nanotubes are now available, which are tiny sensors that allow real-time detection of sub-ppm level C2H413,14. In addition, artificial metalloenzyme-based chemical biosensors have been used to detect ethylene gas spatially by fluorescence in fruits and leaves15. However, it is difficult to detect ppb-level C2H4. Moreover, these sensors respond to several gases (e.g., ethanol, acetaldehyde, and hexane) other than C2H4.

Optical sensing technologies based on laser spectroscopy allow rapid detection of trace VOCs. These include photoacoustic absorption spectroscopy (PAS)16,17, cavity ring-down spectroscopy (CRDS)18,19, and laser absorption spectroscopy (LAS)20,21 using tunable diodes or quantum cascade lasers (QCLs). A detection limit of 0.3 ppb (for 2σ) of C2H4 has been demonstrated with PAS using a CO2 laser as the pump source22. When a quantum cascade laser (QCL) was used as a pump source, a detection limit of 50 ppb of C2H4 was obtained, and C2H4 was successfully detected in the gases released from the apple23. In this case, the gas released from the apple was collected in a slightly complicated manner using a sample bag. The apples were placed in the bag, and a pump fully evacuated the air inside the bag. Then, N2 with 99.999% purity was introduced into the bag until atmospheric pressure was reached. After waiting for at least 15 min, the gas in the bag was used for the measurement. In CRDS, sub-ppb C2H4 detection has been realised using a near-IR distributed feedback (DFB) laser oscillating at 1.6 µm24. However, these optical sensing methods are not yet robust and user-friendly because they require high-power lasers and optical cavities with precision adjustment.

LAS is highly robust and user-friendly compared to PAS and CRDS, owing to its simple measurement setup. Therefore, LAS is used for various forms of gas absorption spectroscopy, although its detection sensitivity is inferior to that of PAS and CRDS. Recently, using a 1.62-µm DFB laser and a 3.27-µm interband cascade laser, respective detection limits of 6.6 and 53 ppb C2H4 have been demonstrated25,26. However, the detection limits of LAS-based optical sensing systems have not yet reached the ppb level. When detecting C2H4 released from plants using optical sensing technologies, it is necessary to place the plant into a sample bag or glass chamber to collect gas. Moreover, a carrier gas such as N2 must be used. Non-destructive optical sensing technology that uses in-situ gas sampling methods in an open environment would represent an advance in biogenic gas analysis technology for plants. For example, they would allow us to observe rapid changes in plant environmental response and identify the source of VOCs. The resulting technology would be useful for early disease diagnosis and stress susceptibility monitoring in the plant physiology and breeding fields, and would facilitate efficient quality control of fruits and vegetables in the postharvest industry.

In this study, we developed a C2H4 detection system based on LAS using a QCL and demonstrated the real-time detection of C2H4 released from apples by non-destructive and in-situ gas sampling in an open environment. When apples were stressed by changes in atmospheric gas concentration or surface temperature, we also succeeded in observing rapid changes in the concentration of C2H4 released from apples.

Results and discussion

Trace gas detection system

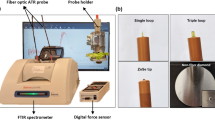

Figure 1 shows a schematic diagram of the C2H4 detection system, which is mainly composed of the mid-IR QCL (QD10500CM1, Thorlabs Inc.), the astigmatic Herriott multi-pass gas cell (AMAC-76, Aerodyne Research), the mid-IR detector (PVI-4TE-10.6, VIGO system), and a gas dilution system. According to the HITRAN database, C2H4 has the strongest absorption lines at approximately 10.5 µm27. Therefore, we selected a single-frequency distributed feedback mid-IR QCL that oscillated at a central wavelength of 10.5 µm (~ 949.5 cm−1). The mid-IR QCL was operated in continuous wave mode, and the typical output power was 10 mW. The mid-IR QCL was controlled at 24 °C by integrated thermoelectric cooling, and the lasing wavelength was swept around the absorption peak at 10.5 µm by current modulation. The QCL output was passed through a lens pair and coupled to a multi-pass gas cell. The multi-pass gas cell provided a long optical pass length of 76 m to detect trace C2H4. The volume of the gas cell was 0.5 L. The output beam from the multi-pass gas cell was focused on the mid-IR detector. The inlet and outlet of the multi-pass gas cell were connected to the apples and scroll pump, respectively. By operating the dry scroll pump and simply making contact between the PTFE tube and the apple, the gas released from the apple was sampled in situ in an open environment without destroying the sample. By controlling the needle valves and mass flows installed at the inlet and outlet of the multi-pass gas cell, it was possible to perform LAS during constant flow of the sampled gas and while maintaining the internal pressure of the gas cell at an arbitrary pressure. By placing the apples in the glass jar connected to the gas dilution system, the atmospheric gas of the apple was also controllable. The gas dilution system was composed of mass flows, reference gases (N2, CO2, C2H4), and a zero-air generator. The CO2 and C2H4 concentrations were adjusted by controlling the flow rate of each reference gas and the zero-air generator. The spectral data were acquired on a PC with a time resolution of 1 s.

Transmission spectra and detection limit

Figure 2 shows the results of the measured transmission spectra of C2H4 and CO2 using the C2H4 detection system. In this measurement, the multi-pass gas cell was directly connected to the gas dilution system without the apple to obtain the spectral data of the reference gases C2H4 and CO2. Here, the absorption intensity was weaker than that of C2H4, but the absorption spectrum of CO2 also appears near 949.48 cm−1. Therefore, this system was able to measure both the C2H4 and CO2 spectra. C2H4 and CO2 were supplied to the multi-pass gas cell from the gas dilution system at concentrations of 10 ppm and 99.995%, respectively, and the transmission spectra were measured while reducing the pressure inside the gas cell from 20 to 4 kPa. By reducing the internal pressure of the gas cell, the pressure broadening of the gas spectra was suppressed, and spectral narrowing of C2H4 and CO2 was observed. These results show that spectral measurement with pressure reduction helps prevent interference between C2H4 and CO2 absorption.

Figure 3 shows the detection signal of the mid-IR detector for different concentrations of C2H4. Here, the value of the absorption peak at 949.35 cm−1 was used as the detection signal. The C2H4 concentrations were adjusted in the range of 25 ppb to 400 ppb by changing the mixing ratio of C2H4 (10 ppm) and N2 (99.999%) reference gases using a gas dilution system. The internal pressure of the gas cell was fixed at 12 kPa, and the measurement time was 3 min at each concentration. A linear fit to the experimental data yielded an R-square value of 0.9872 and an excellent linear response of the sensor. A histogram plot of the detection signal is shown in Fig. 3. The histogram plots were measured inside the gas cell purged with N2, and the standard deviation (σ) of the detection signal was 0.32 mV. Here, the noise equivalent absorption sensitivity (NEAS)28,29 of the C2H4 detection system was calculated as \({\text{NEAS}} = \Delta I/I \cdot L^{ - 1} \cdot f_{bw}^{ - 1/2}\), where \(\Delta I/I\) is the 1σ value of the limiting noise level, \(L\) is the pass length of the gas cell, and \(f_{bw}\) is the detection bandwidth. The \(\Delta I/I\) value of 0.36% was obtained from the histogram plot, so that the NEAS was ~ 1.5 × 10−8 cm−1 Hz−1/2 (\(L = 76\;{\text{m}},\;f_{bw} = 1\;{\text{kHz}}\)). In addition, the detection limit was estimated using three-standard deviations (3σ)30. The 3σ value of 0.96 mV was obtained from the form histogram plot, which corresponded to 0.8 ppb when compared with the linear fitting line in Fig. 3. However, in the lower concentration region (< 100 ppb), some measurement points deviated from the linear fitting line. When supplying low concentration C2H4 using the gas dilution system, the mass flow meter and pressure gauge have to read out a lower flow rate and pressure. Therefore, in the low concentration region, as compared with the high concentration region, the effective measurement accuracies of the mass flow meter and pressure gauge were lowered, which caused the deviation in the low concentration region. The effective quantification limit was estimated to be approximately 2.8 ppb, which was equivalent to ten-standard deviations (10σ)30. The detection ability of ppb-level C2H4 was sufficient to apply this system to the analysis of C2H4 released from plants.

Non-destructive and in-situ sampling of C2H4 released from the apples

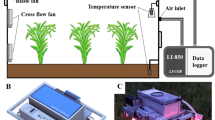

We have demonstrated trace C2H4 detection released from apples by non-destructive and in-situ gas sampling in an open environment. Apples are typical climacteric fruits, characterised by an increase in C2H4 generation and respiration during ripening. In this test, the cultivar ‘Fuji’ was used to clearly detect the source of C2H4 generation in the apple, because it is known to produce remarkably low levels of ethylene gas31,32. Figure 4 shows the locations of C2H4 concentrations. The gases were sampled in situ at the top and bottom of the apple cores and side surfaces of the apples. The sampling flow rate and time were 30 cc/min and 5 min, respectively, and the internal pressure of the gas cell was 12 kPa. Ten apples were used for the measurements. Error bars represent standard deviation. Two apples had cracks on the top of the core, and the other eight apples had no visible cracks. The cracks were from existing natural injuries; they were not intentionally made for the experiment. When using the cracked apples as samples, a C2H4 concentration of 340 ± 160 ppb was detected only at the top of the core. Five of the eight apples without cracks released C2H4 at a concentration of 580 ± 360 ppb from the bottom. In the three remaining apples, C2H4 was not detected in any position. No C2H4 was observed on the side surfaces of any apples. The reason for the absence of C2H4 detection may be that C2H4 released from the side surface was at a much lower concentration than the detection limit. C2H4 release at ~ 100 ppb concentration was observed from the side surface of a few apples when using the PTFE tube with a sucking disk at the tip for gas sampling. However, in this case, the sucking disk quickly sticks to the apple surface, and the apples become stressed by forced gas suction. This sampling method was not stress-free. Additionally, the method is not effective when using plants with bumpy surfaces as samples. Based on the above results, apples without cracks were used as samples in subsequent experiments, and the gas was sampled from the bottom of the core without the sucking disk.

Location dependence of C2H4 concentrations and amount released from apples. Each of the ten apples was sampled in situ to detect released gas at the top and bottom of the core, and the side surface. Five apples released C2H4 from the bottom, and the two apples with a crack on their top released C2H4 from the top. No C2H4 was detected from anywhere in the remaining three apples.

Figure 5 shows the transmittance spectra of C2H4 and CO2 with changing concentrations of CO2 in the atmospheric gas of the apples. The apples were placed in a glass jar, and the concentration of CO2 supplied to the glass jar was controlled between 2.0 and 10.6% using a gas dilution system. The mid-IR absorptions of both C2H4 and CO2 were observed simultaneously in the wavelength region of 949.32–949.52 cm−1. As the CO2 concentration increases from 2.0 to 10.6%, CO2 transmission near 949.48 cm−1 decreases from 75 to 5%, which indicates that CO2 absorption has increased. At the same time, an increase in C2H4 transmission around 949.35 cm−1 was observed. This result shows that C2H4 release from apples decreases as the atmospheric CO2 concentration of the apple increases. It was confirmed that the C2H4 concentration decreased from 2200 to 1200 ppb as the CO2 concentration increased from 2.0 to 10.6%. Using our C2H4 detection system, we succeeded in visualising the suppression of C2H4 production by CO2 treatment, which is a commonly used controlled atmosphere storage method32,33. The same phenomenon was observed in another cultivar termed “Kiou” (data not shown).

The transmittance spectra of gases from apples. Each spectrum shows the changes in the amount of C2H4 released with changing the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere gas of apples. CO2 concentrations were controlled at 2.0, 3.4, 5.7, 8.9, and 10.6% using the gas dilution system. The inset shows the relationship between C2H4 and CO2 concentrations.

Real-time detection of C2H4

Figure 6 shows the results of real-time monitoring of how the C2H4 concentration released by the apple changes with the environmental response. As shown in Fig. 6a, the C2H4 concentration was measured in real time by changing the atmospheric CO2 concentration of the apple. The experimental setup was the same as that in Fig. 5. The CO2 concentration supplied to the glass jar containing the apple was controlled using a gas dilution system. The C2H4 concentration decreased from 1000 to 700 ppb as the CO2 concentration increased to 12%. Then, it returned to 1000 ppb when the CO2 concentration returned to atmospheric concentration. It was observed in real-time that the change in C2H4 concentration was inversely correlated with the change in CO2 concentration. Figure 6b shows the change in the C2H4 concentration when the apple was heated. The apple was soaked in a Dewar vessel filled with water at 22 °C, and a thermocouple for temperature measurement was attached to the apple surface. When the temperature was rapidly increased to 35.5 °C by adding boiling water, the C2H4 concentration increased from 1000 to 1500 ppb. As the temperature decreased, the C2H4 concentration also decreased. We observed for the first time that the C2H4 concentration released from apples changed with a time constant of several minutes in response to environmental changes.

Real-time detection of C2H4 released from apples with CO2 concentration change (a) and the temperature change the of apple surface (b). Blue dots show the changes in C2H4 concentration and amount released from the apple in the gas cell. The red dots in (a) and (b) represent CO2 concentrations around the apple and apple surface temperature, respectively.

C2H4 identification by TD-GC/MS and bioassay

We confirmed the existence of C2H4 in the gas released from the apple by thermal desorption gas chromatography-mass spectroscopy (TD-GC/MS) and bioassays. Adsorbents (MonoTrap RGPS TD, GL Science) were inserted inside the PTFE tube while sampling the apple-released gas to prepare analytical samples for TD-GC/MS. The flow rate in the PTFE tube was 30 cc/min, and the time for the gas to flow through the tube was 90 min. The chromatogram of the gas released from the apples is shown in Fig. 7a. The sampled gas contained various VOCs (e.g., ethylene, acetaldehyde, and ethanol), and each peak identification of the VOCs is shown in Fig. 7a. The peak retention time of C2H4 was observed at 2.2 min. The mass spectrum at 2.2 min shows good agreement with that of C2H4.

C2H4 identified in sample gas released from an apple. (a) Chromatograms of TD-GC/MS analysis for the sample gas. The insets show the C2H4 chromatogram peak at 2.2 min retention time and the mass spectrum of the C2H4. (b) Bioassay of banana ripening. Group (A): bananas without exposure to the gas released from apples. Group (B): bananas with exposure to the gas released from an apple over 24 h.

Next, we demonstrated a banana ripening test as a bioassay using the sample gas, because bananas are also typical climacteric fruits. Figure 7b shows the results of ripening bananas with apple-releasing gas collected by in-situ sampling. We used unripened green bananas as the samples. Gas sampled in situ at a flow rate of 30 cc/min from the apple was allowed into the gas chamber at a volume of 2 L, and the green banana was placed in the glass chamber and exposed to the sampling gas for 24 h. After sample gas exposure, the green banana was removed from the glass chamber, and the ripening process was compared with another green banana which was not exposed to the sample gas. A comparative test was performed at room temperature. As a result, a clear visual difference between both bananas was observable on the third day, confirming that bananas exposed to gas released from the apple ripened faster than the other bananas. This result shows that C2H4 in the apple-releasing gas causes banana ripening by inducing climacteric rise6,34,35,36. The TD-GC/MS and banana ripening tests showed that the gases from the apple we sampled contained C2H4. We confirmed that our C2H4 detection system is effective for the non-destructive real-time monitoring of trace C2H4 released from apples.

Conclusions

In this study, we succeeded in real-time monitoring of C2H4 concentration changes in gas released from apples by non-destructive and in-situ gas sampling in an open environment. Monitoring was demonstrated using an original C2H4 detection system based on LAS. We also demonstrated the rapid concentration changes of C2H4 released from apples when apples were stressed by changes in atmospheric gas concentration or surface temperature. Furthermore, a special sampling chamber or bag is not required, which provides a great advantage in that gas can be sampled from an arbitrary place of fruit. Gas sampling from wounds, lesions caused by diseases and pests, and other localised areas of plants are possible. We expect that our method will allow real-time visualisation of C2H4 dynamics following changes in environmental response. By changing the lasers that make up this gas detection system, various VOCs other than C2H4 can be detected. More detailed information about the plant gas response can be obtained by combining it with conventional GCMS research. Our results show promise in advancing analytical techniques for plant environmental responses.

Methods

Plant materials

We purchased ‘Fuji’ apples (LOPIA Co. Ltd, Saitama, Japan) and used the same cultivar for all experiments and analyses. For the bioassay of banana ripening, we used green bananas (‘Cavendish’) without exposure to C2H4. Green bananas were purchased from Konmatsu Co., Ltd. (Iwate, Japan). During the experiment, both the apples and bananas were stored at 20–22 °C.

Reference gas preparation and internal pressure control of multi-pass gas cell

We prepared three reference gases and a zero-air generator (Zero Air Supply Model-111, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) for the gas dilution system. The three reference gases were C2H4 (10 ppm), G1-CO2 (99.995%), and G1-N2 (99.99995%), and all gases were charged in 10 L high-pressure gas cylinders. According to the manufacturer specifications, the zero-air generator provides dry air without NOx, SO2, O3, CO, and hydrocarbons. All gas supply lines had mass flow meters (Standard Mass Flow Controller MODEL 3660 SERIES, KOFLOC, Kyoto, Japan), and the flow rate could be controlled. By changing the mixing ratio with N2 or zero air, C2H4 and CO2 can be diluted to any concentration. The reference and sampling gases were introduced into the multi-pass gas cell using a dry scroll pump connected to the gas cell. Then, using a needle valve attached to the inlet and outlet of the gas cell, the internal pressure of the gas cell can be adjusted between 2 and 100 kPa while maintaining a constant flow rate in the gas cell.

Thermal desorption-gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (TD-GC/MS)

We used thermal desorption gas chromatography-mass spectroscopy (TD-GC/MS) to analyse numerous VOCs present in the apple-releasing gas. The TD-GC/MS consisted of a GC/MC (GCMS-TQ8040, Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) and a high-performance multimode injector (OPTIC-4, Shimadzu). For the thermal desorption analysis, we used MonoTrap RGPS TD (GL Science) as the absorbent. The adsorbents were inserted into a glass tube (MonoTrap TD Liner for OPTIC/LINEX) and introduced into the injector port for thermal desorption. The initial temperature of the injector port was set at 40 °C, and then the temperature was increased to 230 °C at a rate of 10 °C/s to desorb the VOCs in splitless mode. The desorbed VOCs were concentrated at the headspace of the GC column using cryofocus trapping cooled to − 150 °C. After cryofocus trapping, the GC oven temperature was maintained at 35 °C for 3 min, increased to 200 °C (rising rate = 10 °C/min), and then held at 200 °C for 2 min. An Rt-Q-BOND column (ID = 0.32 mm, length = 30 m, df = 10 μm, RESTEK) was used to separate the eluting compounds, and the carrier gas was high purity He (99.9999%) with a constant flow of 5 ml/min. The MS detector was operated in scan mode from 20 to 300 amu at 200 °C for electron ionisation. C2H4 identification was achieved by comparing the mass spectra and retention times with the reference gases of C2H4. We used GCMSsolution software (Ver. 4.45) and Mass Spectral library (NIST 14) to analyse the retention time and mass spectra, respectively. In this measurement, an apple confirmed to absorption spectral peak of C2H4 by our C2H4 detection system was used as a sample. The thermal desorption analysis using the absorbent was carried out three times and the C2H4 was detected in all measurements.

References

Hunter, D. A., Lange, N. & Reid, M. S. Physiology of flower senescence. In Plant Cell Death Processes (ed. Nooden, L.). 307–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012520915-1/50024-2 (Academic Press, 2004).

Blankenship, S. M. & Kemble, J. Growth, fruiting and ethylene binding of tomato plants in response to chronic ethylene exposure. J. Hortic. Sci. 71(1), 65–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/14620316.1996.11515383 (1996).

Hattori, Y. et al. The ethylene response factors SNORKEL1 and SNORKEL2 allow rice to adapt to deep water. Nature 460(7258), 1026–1030. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature08258 (2009).

Nagai, K. et al. Antagonistic regulation of the gibberellic acid response during stem growth in rice. Nature 584(7819), 109–114. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2501-8 (2020).

Li, T. et al. Apple MdACS6 regulates ethylene biosynthesis during fruit development involving ethylene-responsive factor. Plant Cell Physiol. 56(10), 1909–1917. https://doi.org/10.1093/pcp/pcv111 (2015).

Gwanpua, S. G., Jabbar, A., Tongonya, J., Nicholson, S. & East, A. R. Measuring ethylene in postharvest biology research using the laser-based ETD-300 ethylene detector. Plant Methods 14(1), 205. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13007-018-0372-x (2018).

Feng, X., Apelbaum, A., Sisler, E. C. & Goren, R. Control of ethylene responses in avocado fruit with 1-methylcyclopropene. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 20(2), 143–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0925-5214(00)00126-5 (2000).

Hershkovitz, V., Friedman, H., Goldschmidt, E. E. & Pesis, E. Ethylene regulation of avocado ripening differs between seeded and seedless fruit. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 56(2), 138–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.postharvbio.2009.12.012 (2010).

Iwai, T., Miyasaka, A., Seo, S. & Ohashi, Y. Contribution of ethylene biosynthesis for resistance to Blast Fungus infection in young rice plants. Plant Physiol. 142(3), 1202–1215. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.106.085258 (2006).

Wheeler, R., Peterson, B. V. & Stutte, G. Ethylene production throughout growth and development of plants. Hortic. Sci. 39(7), 1541–1545. https://doi.org/10.21273/HORTSCI.39.7.1541 (2005).

Kamarulzaman, N. H., Le-Minh, N. L. & Stuetz, R. M. Identification of VOCs from natural rubber by different headspace techniques coupled using GC-MS. Talanta 191, 535–544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.talanta.2018.09.019 (2019).

Dailey, A. et al. VOC fingerprints: Metabolomic signatures of biothreat agents with and without antibiotic resistance. Sci. Rep. 10(1), 11746. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-68622-x (2020).

Esser, B., Schnorr, J. M. & Swager, T. M. Selective detection of ethylene gas using carbon nanotube-based devices: Utility in determination of fruit ripeness. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 51(23), 5752–5756. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.201201042 (2012).

Ishihara, S. et al. Cascade reaction-based chemiresistive array for ethylene sensing. ACS Sens. 5(5), 1405–1410. https://doi.org/10.1021/acssensors.0c00194 (2020).

Vong, K. et al. An artificial metalloenzyme biosensor can detect ethylene gas in fruits and Arabidopsis leaves. Nat. Commun. 10(1), 5746. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13758-2 (2019).

West, G. A., Barrett, J. J., Siebert, D. R. & Reddy, K. V. Photoacoustic spectroscopy. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 54(7), 797–817. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1137483 (1983).

Harren, F. J. M., Bijnen, F. G. C., Reuss, J., Voesenek, L. A. C. J. & Blom, C. W. P. M. Sensitive intracavity photoacoustic measurements with a CO2 waveguide laser. Appl. Phys. B 50(2), 137–144. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00331909 (1990).

Anderson, D. Z., Frisch, J. C. & Masser, C. S. Mirror reflectometer based on optical cavity decay time. Appl. Opt. 23(8), 1238. https://doi.org/10.1364/ao.23.001238 (1984).

O’Keefe, A. & Deacon, D. A. G. Cavity ring-down optical spectrometer for absorption measurements using pulsed laser sources. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 59(12), 2544–2551. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.1139895 (1988).

Martin, P. A. Near-infrared diode laser spectroscopy in chemical process and environmental air monitoring. Chem. Soc. Rev. 31(4), 201–210. https://doi.org/10.1039/b003936p (2002).

Nasim, H. & Jamil, Y. Recent advancements in spectroscopy using tunable diode lasers. Laser Phys. Lett. 10(4), 043001. https://doi.org/10.1088/1612-2011/10/4/043001 (2013).

De Gouw, J. A. et al. 2009 Airborne measurements of ethene from industrial sources using laser photo-acoustic spectroscopy. Environ. Sci. Technol. 43(7), 2437–2442. https://doi.org/10.1021/es802701a (2009).

Wang, Z., Li, Z. & Ren, W. Quartz-enhanced photoacoustic detection of ethylene using a 10.5 μm quantum cascade laser. Opt. Express 24(4), 4143–4154. https://doi.org/10.1364/oe.24.004143 (2016).

Wahl, E. H. et al. Ultra-sensitive ethylene postharvest monitor based on cavity ring-down spectroscopy. Opt. Express 14(4), 1673–1684. https://doi.org/10.1364/OE.14.001673 (2006).

Zhang, T., Zhang, G., Liu, X., Gao, G. & Cai, T. A TDLAS sensor for simultaneous measurement of temperature and C2H4 concentration using a differential absorption scheme at high temperature. Fron. Physiol. 8, 44. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphy.2020.00044 (2020).

Li, J., Du, Z., Zhang, Z., Song, L. & Guo, Q. Hollow waveguide-enhanced mid-infrared sensor for fast and sensitive ethylene detection. Sens. Rev. 37(1), 82–87. https://doi.org/10.1108/SR-05-2016-0087 (2017).

Rothman, L. S. et al. The HITRAN2012 molecular spectroscopic database. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 130, 4–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jqsrt.2013.07.002 (2013).

Moser, H., Walter Pölz, W., Waclawek, J. P., Ofner, J. & Lendl, B. Implementation of a quantum cascade laser-based gas sensor prototype for sub-ppmv H2S measurements in a petrochemical process gas stream. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 409, 729–739. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00216-016-9923-z (2017).

Long, D. A., Truong, G. W., van Zee, R. D., Plusquellic, D. F. & Hodges, J. T. Frequency-agile, rapid scanning spectroscopy: Absorption sensitivity of 2 × 10–12 cm−1 Hz−1/2 with a tunable diode laser. App. Phys. B. 144(4), 484–495. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00340-013-5548-5 (2014).

Shrivastava, A. & Gupta, V. B. Methods for the determination of limit of detection and limit of quantitation of the analytical methods. Chron. Young Sci. 2(1), 21–25. https://doi.org/10.4103/2229-5186.79345 (2011).

Jobling, J. J. & McGlasson, W. B. A comparison of ethylene production, maturity and controlled atmosphere storage life of Gala, Fuji and Lady Williams apples (Malus domestica, Borkh.). Postharvest Biol. Technol. 6(3–4), 209–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/0925-5214(94)00002-A (1995).

Harada, T. et al. An allele of the 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate synthase gene (Md-ACS1) accounts for the low level of ethylene production in climacteric fruits of some apple cultivars. Theor. Appl. Genet. 101(5–6), 742–746. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001220051539 (2000).

Gorny, J. R. & Kader, A. A. Controlled-atmosphere suppression of ACC synthase and ACC oxidase in ‘Golden Delicious’ apples during long-term cold storage. J. Am. Soc. Hort. Sci. 121(4), 751–755. https://doi.org/10.21273/JASHS.121.4.751 (1996).

Hartman, S. MaXB3 limits ethylene production and ripening of banana fruits. Plant Physiol. 184(2), 568–569. https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.20.01140 (2020).

Saltveit, M. E. Effect of ethylene on quality of fresh fruits and vegetables. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 15(3), 279–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0925-5214(98)00091-X (1999).

Terai, H., Ueda, Y. & Ogata, K. Studies on the mechanism of ethylene action for fruits ripening I. J. Jpn. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 42(1), 75–80. https://doi.org/10.2503/jjshs.42.75 (1973).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Public/Private R&D Investment Strategic Expansion Program (PRISM).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.Y. conceived and conducted the experiments and wrote the manuscript with contributions from all authors. Y.K. and T.A. performed the experiments and analysed the data. T.M. proposed the concept of GC/MS and bioassay experiments. S.W. supervised the Project. All the authors contributed to the discussion and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yumoto, M., Kawata, Y., Abe, T. et al. Non-destructive mid-IR spectroscopy with quantum cascade laser can detect ethylene gas dynamics of apple cultivar ‘Fuji’ in real time. Sci Rep 11, 20695 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-00254-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-00254-1

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.