Abstract

Trichoderma harzianum is a filamentous fungus used as a biological control agent for agricultural pests. Genes of this microorganism have been studied, and their applications are patented for use in biofungicides and plant breeding strategies. Gene editing technologies would be of great importance for genetic characterization of this species, but have not yet been reported. This work describes mutants obtained with an auxotrophic marker in this species using the CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats)/ Cas (CRISPR-associated) system. For this, sequences for a guide RNA and Cas9 overexpression were inserted via biolistics, and the sequencing approach confirmed deletions and insertions at the pyr4 gene. Phenotypic characterization demonstrated a reduction in the growth of mutants in the absence of uridine, as well as resistance to 5-fluorotic acid. In addition, the gene disruption did not reduce mycoparasitc activity against phytopathogens. Thus, target disruption of the pyr4 gene in T. harzianum using the CRISPR/Cas9 system was demonstrated, and it was also shown that endogenous expression of the system did not interfere with the biological control activity of pathogens. This work is the first report of CRISPR Cas9-based editing in this biocontrol species, and the mutants expressing Cas9 have potential for the generation of useful technologies in agricultural biotechnology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Species of the fungal genus Trichoderma are important biocontrol agents (BCAs) used in agriculture, and they are also industrial producers of enzymes1,2,3,4,5. Several bioformulations have been reported as both mycoparasites and nematode parasites and are already registered3,6. Additionally, there are a number of studies on biotechnological applications of enzymes from these organisms for biodiesel production4,5,7,8 and in transgenic plants leading to resistance to biotic and abiotic stresses9,10. Therefore, efficient molecular tools are essential for structural and functional genomics investigations in Trichoderma industrial and biocontrol species6,11,12.

Based on studies in a number of filamentous fungi, it is very difficult to achieve gene deletion in Trichoderma biocontrol strains using traditional genetic approaches13,14,15. They have an inefficient homologous recombination machinery and, because the fungus reproduces asexually, it prefers to perform non-homologous recombination, which results in a low frequency of correct genomic integration16,17,18,19,20. These challenges could be overcome by the CRISPR/Cas9 system, a gene editing technique in which nucleotides can be inserted, replaced or removed from the genome through endonucleases13,19,20,21. To date, work on the CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing system has occurred exclusively in Trichoderma reesei, and has been able to generate either selective markers or strains with increased protein production16,20,21. However, this species is an industrial producer of cellulases and hemicellulases that already present a high number of mutants produced using traditional genetic approaches, including strains with pyr as an auxotrophic marker22,23,24,25.

Trichoderma harzianum is a soil-borne fungus used in biofungicides for the biological control of agricultural diseases that affect crops of economic importance, such as soybean, rice, corn, tomato, tobacco, and bean11,26,27. This microorganism is cosmopolitan and performs biocontrol through several mechanisms of action, including antibiosis, competition for nutrients and mycoparasitism, in addition to promoting plant growth, inducing greater tolerance to stresses and increasing seed germination rates2,28,29. These beneficial effects promoted by T. harzianum on plants are possible due to their ability to colonize and penetrate the roots of plants and to carry out symbiotic relationships2,3,11,12.

Due the fact that T. harzianum is among the bioagents most used in today’s agriculture worldwide11,30,31, there is increasing interest in understanding the modes of action of this biocontrol fungus and the underlying molecular processes in greater detail. The recent development of the CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing technique could form the basis for large-scale genetic manipulations of this biocontrol fungus, but the establishment of additional selection markers is also crucial. Thus far, only a limited number of selection markers have been available for genetic transformation of T. harzianum, and OMP-decarboxylase deletion (pyr −) has proved to be a reliable auxotrophic marker for filamentous fungi5,14,22,32,33. Furthermore, the effects of gene deletion together with Cas9 overexpression in a biocontrol fungus is innovative. The use of the CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing system to disrupt the pyr4 gene in T. harzianum represents a promising strategy for validating the technique in this fungus; it also prepares the ground for further work on gene editing and the functional analysis of this system during mycoparasitism.

Results and discussion

Since genetic tools have scarcely been developed for most filamentous fungus, it is currently difficult to employ genetic engineering in understanding the biology of Trichoderma spp. and to fully exploit them industrially8,34. Moreover, the frequency of homologous recombination in some species is traditionally very low, time-consuming and sometimes troublesome16,19,20,33. For these reasons, there is a demand for developing versatile methods that can be used to genetically manipulate this biocontrol species. Therefore, gene editing technologies represent a highly promising alternative in genetic engineering of T. harzianum and have prompted us to establish new mutant lines for large-scale genetic manipulations. To facilitate this, we have developed a CRISPR/Cas9-based system adapted for use in this biocontrol fungus.

To CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing, both the endonuclease and the sgRNA need to be present in the nucleus of the target organism13. In order to create vectors suitable for pyr4 gene editing in T. harzianum, the respective Cas9 sequence was inserted in pNOM102 plasmid35, under control of the A. nidulans gpdA promoter and trpC terminator. Subsequently, the gRNA sequence for pyr4 was inserted in pLHhph1-tef136 plasmid, containing a hygromycin phosphotransferase gene (hyg) from E. coli as a dominant selectable marker. The resulting plasmids, pCas and pGpyr4 (Fig. 1), were used for fungal transformation procedure.

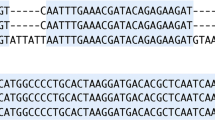

Screening of T. harzianum mutants resistant to 5′-FOA. (A) Schematic representation of vectors used to transform fungus spores. (B) Genomic DNA of T. harzianum wild-type (WT) and FOA-resistant mutants (ΔP3, ΔP4, ΔP7, and ΔP13) was isolated and screened by PCR for the presence of the Cas9 gene which yielded a specific amplicon of 1242-bp. (C) Phenotype and growth of T. harzianum wild-type (WT) and FOA-resistant mutants (ΔP3, ΔP4, ΔP7, and ΔP13). *Bars marked with asterisk differ significantly (P < 0.05). (D) A fragment from pyr4, which was used for sequencing, confirmed mutants’ indels at target region. The sgRNA guiding sequence is highlighted in bold.

Protoplast transformation of Trichoderma species includes PEG/CaCl2, electroporation, and A. tumefaciens-mediated strategies. However, preparation of protoplasts using various cell-wall degrading enzymes is time-consuming and expensive. In this way, biolistic bombardment is simple and versatile, as plasmids can be delivered into Trichoderma intact conidia.

Disruption of pyr4 confers 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA) resistance to T. harzianum. Mutants which are defective in pyr4 are prototrophic strains resistant to 5-FOA, which is converted by orotidine-5′-monophosphate (OMP)-decarboxylase to the toxic intermediate 5-fluoro-UMP37. In this work, biolistic have been employed successfully for introducing Cas9 and gRNA in T. harzianum, and positive transformants presented both plasmids by PCR, as described in the materials and methods section. Colonies began to appear 3 days after plating of conidia on selective medium containing 5-FOA and uridine. Fourteen transformants were generated in two bombardment experiments (12 plates), with an efficiency of between 0 and 3 co-transformants per plate. Four T. harzianum mutants (named ΔP3, ΔP4, ΔP7 and ΔP13) that showed the codon-optimized Cas9 gene (Fig. 1B) after selection in 5-FOA medium and single spore isolation (Fig. 1C) were used for assays.

Correspondingly, sequencing approaches were used to carry out a comparative pyr4 analysis with the wild-type strain, and indels at the gRNA target were shown for all mutants (Fig. 1D). Thus, the CRISPR/Cas9 technique enabled the production of T. harzianum strains with an auxotrophic marker that also expressed the Cas9 gene. From a practical perspective, our work introduces a powerful genome-editing approach in mitotically stable mutants with endogenous pyr4 gene disruption accomplished by Cas9 expression. This system could be versatile and simple, as new mutagenesis can be achieved in T. harzianum lines by re-transforming with a single plasmid containing RNA guide.

One of the most important advancements in recent years, for improving the performance of research with Trichoderma species is the development of auxotrophic strains. Disruption of pyr4 also generates auxotrophic strains defective for uridine (uracil). In our work, we present the successful establishment of this selection marker for the genetic transformation of the biocontrol fungus T. harzianum. Indeed, results from assays in PDA medium without uridine demonstrated that mutants (ΔP3, ΔP4, ΔP7 and ΔP13) presented lower growth ratios compared to the wild-type (WT) strain (Fig. 2A). Moreover, assays in PDA with uridine revealed that all mutants showed higher growth ratios compared to WT (Fig. 2A). In relation to assays conducted in MEX medium, it was demonstrated that pyr4 disruption also reduced the mutants’ growth ratio in the absence of uridine. However, addition of uridine to MEX medium only reestablished mutants’ growth ratio similarly to WT (Fig. 2B). In this way, the CRISPR/Cas9 system caused insertions and deletions (indels) in target regions of the pyr4 gene and successfully interrupted gene function. In addition, phenotypic analyses confirmed that these mutants need a complement of uridine in the medium to present similar growth to the wild-type, thus certifying the presence of this convenient selection marker.

Phenotype analysis of T. harzianum mutants for uridine auxotrophy. T. harzianum wild-type and mutants (ΔP3, ΔP4, ΔP7, and ΔP13) were grown at 28 °C in absence or presence of uridine. Pictures after 2 days from bioassays conducted in PDA (A) and MEX (B) media. *Bars marked with asterisk differ significantly (P < 0.05).

Microorganisms with pyr-negative marker are widely used in biotechnological processes, industries and research14,21,25. Indeed, genomic research with the industrial species T. reesei entered a new era after pyr-negative strains became available. Nevertheless, T. reesei with this auxotrophic marker has been produced using both traditional genetic approaches22,25 and, recently, CRISPR/Cas9 technology20. Additionally, research using the CRISPR/Cas9 system reveals that these markers are exclusive to T. reesei15,16,20,38. These studies used protoplast or Agrobacterium transformation methods and described only in vitro transcription of gRNA15,16,20,38. Our work was successfully carried out by biolistic direct transformation of T. harzianum with the Cas9/gRNA complex, and it may be an alternative means to achieve fast gene disruption, while the overexpression of a codon-optimized Cas9 provides a means to speed up genome editing in this biocontrol fungus. In addition, the use of Cas9 and gRNA in separate plasmids allows the generation of new edition vectors by manipulating only the gRNA vector in a simple and cheaper manner. Mutants overexpressing Cas9 could be re-transformed with new gRNA vectors, taking advantage of the pyr4 auxotrophic marker. Despite these advantages, there has been no report of using such a technique in other Trichoderma biocontrol species.

Trichoderma harzianum is a cosmopolitan filamentous fungus that displays a remarkable range of applications in agricultural biotechnology2,3. Because of its ability to antagonize plant–pathogens as well as stimulating plant growth and defense responses, some strains are used in bioformulation for biological control2,11,26,27. In this way, gene disruption has been a critical technique for improvement of T. harzianum strains and biocontrol studies.

The effects of pyr4 disruption and Cas9 overexpression on the mycoparasitic interaction between T. harzianum and fungal hosts were assessed in plate confrontation assays. In relation to S. sclerotiorum assays, we observed that the absence of uridine did not affect mutants’ ability to mycoparasitize this pathogen, compared to the WT strain (Fig. 3A). However, confrontation assays carried out in the presence of uridine demonstrated that mutants decreased S. sclerotiorum overgrowth compared to wild-type (Fig. 3A).

Mycoparasitic abilities of uridine auxotrophic mutants. The antagonistic activity of mutants (ΔP3, ΔP4, ΔP7, and ΔP13) in comparison to the T. harzianum wild-type was assessed in plate confrontation assays using Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (A) or Fusarium oxysporum (B) as host fungus. Bioassays were conducted in presence and absence of uridine. *Bars marked with asterisk differ significantly (P < 0.05).

Confrontation assays were also performed to compare mycoparasitic abilities of T. harzianum strains against F. oxysporum either in absence or presence of uridine (Fig. 3B). No differences between the tested strains were observed for the inhibition of F. oxysporum in all media analyzed (Fig. 3B). Bioassays with pathogens demonstrated that pyr4 gene disruption (OMP-decarboxylase), important for the pyrimidine synthesis pathway, in addition to Cas9 expression, did not reduce the mycoparasitic activity of mutants. Thus, our results underscore the use of the CRISPR/Cas9 system in T. harzianum has many prospects for functional analysis of biocontrol genes, metabolic modifications, and the selection or production of new strains for biotechnological uses.

Conclusion

For the first time, this work successfully established a promising approach for genome editing in the biocontrol fungus T. harzianum. Mutants produced with an auxotrophic marker and Cas9 overexpression provide a tool for functional analysis of biocontrol genes, selection of strains for bioformulations, and the generation of new strains for biotechnological uses.

Materials and methods

Microorganisms and culture conditions

Trichoderma harzianum ALL42 (Enzymology group collection—UFG/ICB) was used for this study. Fusarium oxysporum and Sclerotinia sclerotiorum were from the EMBRAPA–CNPAF culture collection. The microorganisms were maintained on potato/dextrose/agar (PDA) plates with periodic sampling and stored at 4 °C in EMBRAPA/CNPAF before use.

Construction of the CRISPR/Cas9 gene edition system

For the construction of the CRISPR/Cas9 editing system, the Cas9 gene coding sequence from S. pyogenes was codon-optimized for expression in Trichoderma harzianum and synthesized by Epoch Life Science, Inc. (Sugar Land, TX, USA) (Supplementary Material). The Cas9 sequence was inserted in the pNOM102 plasmid35 between the constitutive A. nidulans gpdA promoter (GenBank accession number: Z32524.1, position 61 to 2129) and trpC terminator (GenBank accession number: X02390.1, position 3466 to 4168), generating the vector pCas. The gRNA sequence for pyr4 (JGI ID: 480432, Fig. 1) edition was designed using the online E-CRISPR design server (http://www.e-crisp.org/E-CRISP/) and inserted downstream of the constitutive H. jecorina (T. reesei) tef1 promoter of the plasmid pLHhph1-tef136, generating the vector pGpyr4. The two final vectors (pCas and pGpyr4; Fig. 1) were used for biolistic transformation in a 1:1 molar ratio.

Preparation of microparticles and cells for bombardment, and biolistic co-transformation of T. harzianum

Transformation procedure was based on previous protocols18,39,40, with some essential modifications described in the following. DNA was bound to 0.2-μ-diameter tungsten particles (M5, Sylvania Inc.) by mixing sequentially in a microcentrifuge tube: 50 μl microparticles (60 mg ml−1 in 50% glycerol), 5 μl (1 μg μl −1) of each plasmid constructed (pCas and pGpyr4), 50 μl CaCl2 (2.5 M) and 20 μl spermidine free-base (100 mM). After 10 min incubation, the DNA-coated microparticles were centrifuged (15,000×g, 10 s) and the supernatant removed. The pellet was washed with 150 μl 70% ethanol and then with absolute ethanol. The final pellet was resuspended in 24 μl of absolute ethanol and sonicated for 2 s, just before use. Aliquots of 3 μl were spread onto carrier membranes (Kapton, 2 mil, DuPont) which were allowed to evaporate in a desiccator at 12% relative humidity.

The target material for transformation by microparticle bombardment was Trichoderma harzianum (ALL42) intact conidia. A suspension of conidia, previously produced by cultivation of the fungus on potato-dextrose agar was prepared by harvesting the conidia from the plate, suspending them in 0.9 M NaCl, and separating them from mycelial carryover by filtration through a column filled with glasswool. A conidial suspension (30 μl) containing 1.7 × 107 spores ml−1 was bombarded with the DNA-coated microparticles utilizing a high pressure helium-driven particle acceleration device built in our laboratory40. The relative humidity in the biolistic laboratory was 50%, the gap distance from shock wave generator to the carrier membrane was 8 mm, the carrier membrane flying distance to the stopping screen was 13 ram, the DNA-coated microparticles flying distance to the target was 80 mm, the vacuum in the chamber was 27 inches of Hg and the helium pressure utilized in all experiments was 1 200 psi. After the bombardment, transformants were incubated at 28 °C on yeast extract/agar (MEX) plates containing 5-FOA (1.5 g/L; Fermentas, St. Leon-Rot, Germany) and uridine (10 mM).

Selection and stabilization of co-transformants

Inoculated plates were incubated at 28 °C for up to 10 days during which plates were periodically examined directly for Trichoderma harzianum conidia development. Colonies appearing after incubation were picked using a sterile needle and transferred to fresh selective medium. Mutants were sub-cultured for a further three cycles of mycelial growth and conidiation.

Molecular analysis of T. harzianum mutants and sequencing

Following three rounds of single-spore isolation, we obtained 14 mutants by phenotypic analysis (5′FOA resistance). Genomic DNA from four co-transformed strains were isolated as described previously22 and screened by PCR amplification with primers specific for pCas cassette (Cas9_RNAgCheC: 5′-CTGCAAGGCGATTAAGTTGG-3′/ Cas9_3897F: 5′-ACAGCATAAGCACTACCTCG-3′) and also pGpyr4 vector (hygF:5′-CACGTTGCAAGACCTGCCTGAA-3′/ hygR:5′-TCCGGATGCCTCCGCTCGAAGTA-3′). The amplification conditions were: an initial denaturation step of 2 min at 94 °C, followed by 30 cycles of 30 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 55 °C and 60 s at 72 °C, and a final extension step of 10 min at 72 °C. The pyr4 gene fragment, which was used for sequencing and further analysis, was amplified (pyrF: 5′-AGCTCTAACCTGTGCCTGA-3′/ pyrR: 5′-AAGGTAGAGGAGCTCCCG-3′), cloned into the pGEMT-Easy vector according to standard procedures and sequenced using SP6 universal primer. DNA from the wild type (WT) strain was included as control.

Growth and direct confrontation assays

To analyze Trichoderma harzianum mutants for uridine auxotrophy, mycelium-covered plugs were placed at the center of fresh PDA or MEX plates supplemented with 10 mM uridine and incubated at 28 °C for 7 days. Antagonism activity of T. harzianum WT and mutants against pathogens was performed as a plate confrontation assay as described previously41, and colony diameter measurement was taken for a period of 7 days. Two pathogens (Sclerotinia sclerotiorum and Fusarium oxysporum) were independently evaluated during confrontation with T. harzianum strains in presence and absence of uridine. All experiments were performed using three biological replicates.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed for normality (Shapiro–Wilk’s tests) and for homogeneity (Bartlett’s tests). Data that were not normal were transformed using (x + 0.5)1/2. Afterwards, data were subjected to ANOVA, and means were separated by Dunnett’s test at 5% probability whenever ANOVA was significant. The statistical analysis was performed using software R, version 3.2.2 (R Core Team, 2016), and graphical work was carried out using GraphPad Prism version 7.0 software (La Jolla, CA, USA).

References

Druzhinina, I. S. et al. Trichoderma: The genomics of opportunistic success. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9, 749–759 (2011).

Adnan, M. et al. Plant defense against fungal pathogens by antagonistic fungi with Trichoderma in focus. Microb. Pathog. 129, 7–18 (2019).

Harman, G. E. & Uphoff, N. Symbiotic root-endophytic soil microbes improve crop productivity and provide environmental benefits. Scientifica 2019, 9106395 (2019).

Novy, V., Nielsen, F., Seiboth, B. & Nidetzky, B. Biotechnology for biofuels the influence of feedstock characteristics on enzyme production in Trichoderma reesei: A review on productivity, gene regulation and secretion profiles. Biotechnol. Biofuels https://doi.org/10.1186/s13068-019-1571-z (2019).

Druzhinina, I. S. & Kubicek, C. P. Genetic engineering of Trichoderma reesei cellulases and their production. Microb. Biotechnol. 10, 1485–1499 (2017).

Naranjo-Ortiz, M. A. & Gabaldón, T. Fungal evolution: Major ecological adaptations and evolutionary transitions. Biol. Rev. 94, 1443–1476 (2019).

Jiang, D. et al. Molecular tools for functional genomics in fi lamentous fungi: Recent advances and new strategies. Biotechnol. Adv. 31, 1562–1574 (2013).

Schuster, A. & Schmoll, M. Biology and biotechnology of Trichoderma. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 87, 787–799 (2010).

Nicolás, C., Hermosa, R., Rubio, B., Mukherjee, P. K. & Monte, E. Trichoderma genes in plants for stress tolerance- status and prospects. Plant Sci. 228, 71–78 (2014).

Vieira, P. M. et al. Overexpression of an aquaglyceroporin gene from Trichoderma harzianum improves water-use efficiency and drought tolerance in Nicotiana tabacum. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 121, 38–47 (2017).

Silva, R. N. et al. Trichoderma/pathogen/plant interaction in pre-harvest food security. Fungal Biol. 123, 565–583 (2019).

Adnan, M. et al. Microbial Pathogenesis Plant defense against fungal pathogens by antagonistic fungi with Trichoderma in focus. Microb. Pthogenes 129, 7–18 (2019).

Schuster, M. & Kahmann, R. CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing approaches in filamentous fungi and oomycetes. Fungal Genet. Biol. 130, 43–53 (2019).

Ruiz-Díez, B. Strategies for the transformation of filamentous fungi. J. Appl. Microbiol. 92, 189–195 (2002).

Song, R. et al. CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing technology in filamentous fungi: progress and perspective. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 103, 6919–6932 (2019).

Liu, R., Chen, L., Jiang, Y., Zou, G. & Zhou, Z. A novel transcription factor specifically regulates GH11 xylanase genes in Trichoderma reesei. Biotechnol. Biofuels 10, 1–14 (2017).

Zeilinger, S. Gene disruption in Trichoderma atroviride via Agrobacterium-mediated transformation. Curr. Genet. 45, 54–60 (2004).

Vieira, P. M. et al. Overexpression of an aquaglyceroporin gene in the fungal biocontrol agent Trichoderma harzianum affects stress tolerance, pathogen antagonism and Phaseolus vulgaris development. Biol. Control 126, 185–191 (2018).

Wang, Q. & Coleman, J. J. Progress and challenges: Development and implementation of CRISPR/Cas9 technology in filamentous fungi. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 17, 761–769 (2019).

Liu, R., Chen, L., Jiang, Y., Zhou, Z. & Zou, G. Efficient genome editing in filamentous fungus Trichoderma reesei using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Cell Discov. 1, 1–11 (2015).

Rantasalo, A. et al. Novel genetic tools that enable highly pure protein production in Trichoderma reesei. Sci. Rep. 9, 5032 (2019).

Gruber, F., Visser, J., Kubicek, C. P. & de Graaff, L. H. The development of a heterologous transformation system for the cellulolytic fungus Trichoderma reesei based on a pyrG-negative mutant strain. Curr. Genet. 18, 71–76 (1990).

Jørgensen, M. S., Skovlund, D. A., Johannesen, P. F. & Mortensen, U. H. A novel platform for heterologous gene expression in Trichoderma reesei (Teleomorph Hypocrea jecorina). Microb. Cell Fact. 13, 1–9 (2014).

Long, H., Wang, T. H. & Zhang, Y. K. Isolation of Trichoderma reesei pyrG negative mutant by UV mutagenesis and its application in transformation. Chem. Res. Chin. Univ. 24, 565–569 (2008).

Steiger, M. G. et al. Transformation system for Hypocrea jecorina (Trichoderma reesei) that favors homologous integration and employs reusable bidirectionally selectable markers. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 114–121 (2011).

Vieira, P. M. et al. Identification of differentially expressed genes from Trichoderma harzianum during growth on cell wall of Fusarium solani as a tool for biotechnological application. BMC Genom. 14, 177 (2013).

Mukherjee, P. K. A novel seed-dressing formulation based on an improved mutant strain of Trichoderma virens, and its field evaluation. Front. Microbiol. 10, 1–13 (2019).

Guzm, P., Porras-troncoso, D., Olmedo-monfil, V. & Herrera-estrella, A. Trichoderma species : versatile plant symbionts. Phtopathology https://doi.org/10.1094/PHYTO-07-18-0218-RVW (2019).

Mendoza-Mendoza, A. et al. Molecular dialogues between Trichoderma and roots: role of the fungal secretome. Fungal Biol. Rev. 32, 62–85 (2018).

Kubicek, C. P. et al. Comparative genome sequence analysis underscores mycoparasitism as the ancestral life style of Trichoderma. Genome Biol. 12, R40 (2011).

Mukherjee, M. et al. Trichoderma–plant–pathogen interactions: advances in genetics of biological control. Indian J. Microbiol. 52, 522–529 (2012).

Calcáneo-Hernández, G., Rojas-Espinosa, E., Landeros-Jaime, F., Cervantes-Chávez, J. A. & Esquivel-Naranjo, E. U. An efficient transformation system for Trichoderma atroviride using the pyr4 gene as a selectable marker. Braz. J. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42770-020-00329-7 (2020).

Derntl, C., Kiesenhofer, D. P., Mach, R. L. & Mach-Aigner, A. R. Novel strategies for genomic manipulation of Trichoderma reesei with the purpose of strain engineering. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81, 6314–6323 (2015).

Lorito, M., Woo, S., Harman, G. & Monte, E. Translational research on Trichoderma: from ’omics to the field. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 48, 395–417 (2010).

Pamphile, J. A., da Rocha, C. L. M. S. C. & Azevedo, J. L. Co-transformation of a tropical maize endophytic isolate of Fusarium verticillioides (synonym F. moniliforme) with gusA and nia genes. Genet. Mol. Biol. 27, 253–258 (2004).

Akel, E., Metz, B., Seiboth, B. & Kubicek, C. P. Molecular regulation of arabinan and L-arabinose metabolism in Hypocrea jecorina (Trichoderma reesei). Eukaryot. Cell 8, 1837–1844 (2009).

Hu, H., Boone, A. & Yang, W. Mechanism of OMP decarboxylation in orotidine 5′-monophosphate decarboxylase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 14493–14503 (2008).

Hao, Z. & Su, X. Fast gene disruption in Trichoderma reesei using in vitro assembled Cas9/gRNA complex. BMC Biotechnol. 19, 1–7 (2019).

Inglis, P. W., Aragão, F. J., Frazão, H., Magalhães, B. P. & Valadares-Inglis, M. C. Biolistic co-transformation of Metarhizium anisopliae var. acridum strain CG423 with green fluorescent protein and resistance to glufosinate ammonium. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 191, 249–254 (2000).

Aragão, F. J. L. et al. Inheritance of foreign genes in transgenic bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) co-transformed via particle bombardment. Theor. Appl. Genet. 93, 142–150 (1996).

Gomes, E. V. et al. The Cerato-Platanin protein Epl-1 from Trichoderma harzianum is involved in mycoparasitism, plant resistance induction and self cell wall protection. Sci. Rep. 5, 17998 (2015).

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq- 433198/2018-4 and 307111/2018-0).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Designed the vectors and planned the experiments: P.M.V., G.R.V., and F.J.L.A. Fungal transformation: P.M.V. and G.R.V. Molecular analyses: P.M.V., A.A.V., J.C. Performed fungal bioassays: A.A.V. and P.M.V. Analyzed the data: P.M.V. and A.A.V. Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: F.J.L.A., G.R.V., and P.M.V. Wrote the paper: P.M.V. and A.A.V. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vieira, A.A., Vianna, G.R., Carrijo, J. et al. Generation of Trichoderma harzianum with pyr4 auxotrophic marker by using the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Sci Rep 11, 1085 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-80186-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-80186-4

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.