Abstract

Ovarian cancer is one of the most common cancers in women and is often diagnosed as advanced stage because of the subtle symptoms of early ovarian cancer. To identify the somatic alterations and new biomarkers for the diagnosis and targeted therapy of Chinese ovarian cancer patients, a total of 65 Chinese ovarian cancer patients were enrolled for detection of genomic alterations. The most commonly mutated genes in ovarian cancers were TP53 (86.15%, 56/65), NF1 (13.85%, 9/65), NOTCH3 (10.77%, 7/65), and TERT (10.77%, 7/65). Statistical analysis showed that TP53 and LRP1B mutations were associated with the age of patients, KRAS, TP53, and PTEN mutations were significantly associated with tumor differentiation, and MED12, LRP2, PIK3R2, CCNE1, and LRP1B mutations were significantly associated with high tumor mutational burden. The mutation frequencies of LRP2 and NTRK3 in metastatic ovarian cancers were higher than those in primary tumors, but the difference was not significant (P = 0.072, for both). Molecular characteristics of three patients responding to olapanib supported that BRCA mutation and HRD related mutations is the target of olaparib in platinum sensitive patients. In conclusion we identified the somatic alterations and suggested a group of potential biomarkers for Chinese ovarian cancer patients. Our study provided a basis for further exploration of diagnosis and molecular targeted therapy for Chinese ovarian cancer patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ovarian cancer is one of the most common gynecological malignant tumors worldwide. Since morbidity and mortality are increasing year by year, ovarian cancer has become a real threat to women's health and survival1,2. Patients with early stage ovarian cancer can typically undergo surgical treatment, but those with advanced stage or metastasis usually do not have specific treatment options, and therefore, the prognosis is poor3,4. The initial treatment for advanced ovarian cancer is usually debulking surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy or neoadjuvant therapy5. However, 5-year survival rates of ovarian cancer are less than 50%2. Therefore, understanding the mechanism of tumorigenesis and developing potential biomarkers for diagnosis and targeted therapy would be of great clinical value for ovarian cancer.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) technology has been widely used in molecular genetic research of various tumors6,7,8. Recently, a series of studies on the mutational landscape of ovarian cancer have been reported9,10. Balendran et al. identified the most commonly altered genes in brain metastatic ovarian cancer to be BRCA1/2, TP53, and ATM10. TP53 was the most commonly mutated gene in all ovarian cancer subtypes9. A study on a cohort of patients with epithelial ovarian cancer identified 77.4% of patients having at least one somatic or germline mutation, and that the most frequent germline and somatic mutations were BRAC1/2 and TP53 mutations, respectively11. There are many subtypes of ovarian cancer and these histological types have different carcinogenesis mechanisms, which leads to potentially different treatment options for each subtype12,13. According to the FIGO Cancer Report 2018, epithelial ovarian cancers were the most common type, and high-grade serous ovarian cancer (HGSOC) was the most common subtype14. Garziera et al. found a heterogeneous mutational landscape and poorer prognosis in HGSOC patients harboring concurrent mutations of 2 driver actionable genes in the 26-cancer-gene panel15. Targeted NGS showed potential advantage for identifying subgroups of patients with distinct therapeutic vulnerabilities based on the mutational profile expressed by ovarian cancers15. A bioinformatics analysis of mutational and clinical data of 334 HGSOC tumor samples from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) revealed a sub-cluster of high-frequency mutations in 58 genes associated with DNA damage repair, apoptosis, and cell cycle regulation in 22 patients, indicating that germline mutations of CHECK2, RPS6KA2, and MLL4 genes could be used as a risk factor predictor for women16. Also, Kuo et al. had reported that CDKN2A/B, CSMD1, and DOCK4 were the most common alterations in HGSOC17, and Ganapathi et al. found that COL2A1 and pseudogene SLC6A10P could be used for predicting tumor recurrence in HGSOC18. However, patients from different races or geographic regions often have different mutational characteristics. Analyzing the mutational characteristics of patients in China could complement and improve the knowledge of molecular characteristics of ovarian cancers as a whole and provide evidence for diagnosis and targeted therapy for ovarian cancers. Therefore, we enrolled 65 Chinese ovarian cancer patients in this study and performed NGS testing to identify characteristics of genomic alterations (GAs) and potential biomarkers for diagnosis and targeted therapy of ovarian cancers.

Patients and methods

Patient enrollment and sample collection

A total of 65 ovarian cancer patients were enrolled in this study from Zhejiang Cancer Hospital. Informed consent was obtained from all patients and this study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee. Both formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tumor tissues, including 49 primary lesions, 10 metastatic lesions, and 6 lesions with unknown origin, and matched blood samples were collected from enrolled patients. FFPE samples containing at least 20% of tumor cells were used for NGS detection. Genomic DNA was isolated by using QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit and QIAamp DNA Blood Midi Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentration of DNA was measured by Qubit and normalized to 20–50 ng/μL.

Identification of GAs and tumor mutational burden (TMB)

The genomic information of 59 ovarian cancer patients was produced by using the YuanSu450 gene panel, which covers all of the coding exons of 450 cancer-related genes and 64 selected introns in 39 genes that are frequently rearranged in solid tumors (supplementary material 1), and the genomic information of 6 olaparib sensitive patients was produced by whole exome sequencing (WES). The mean depth of Yuansu450 gene panel was 800 × (range: 320–2727), and the mean depth of WES was 500 × (range: 122–1814). All sequencing data were obtainedby using Illumina NextSeq 500 (Illumina, Inc., CA) in OrigiMed laboratory certified by College of American Pathologists (CAP) and Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA). GAs were identified followed previous study19,20. Single nucleotide variants (SNVs) were identified by MuTect (v1.7). Insertion-deletions (Indels) were identified by using PINDEL (V0.2.5). The raw calls of SNV and short Indel were further selected as follows: A minimum of 5 reads was required to support alternative calling. Variants with read depths less than 30 × with strand bias larger than 10% or VAF < 0.5% were removed. The functional impact of GAs was annotated by SnpEff3.0. Copy number variation (CNV) regions were identified by Control-FREEC (v9.7) with the following parameters: window = 50,000 and step = 10,000. Gene fusions/rearrangements were detected through an in-house developed pipeline: paired-end reads with abnormal insert size of over 2000 bp aligned to the same chromosome or aligned to different chromosomes were collected and a discordant paired clusters according to the pairing relationship, then consistent breakpoints from the paired-end discordant reads within a cluster were identified to establish potential fusion/rearrangement breakpoints. Gene fusions/rearrangements were assessed by Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV). Germline variants were filtered from database of the 1000 Genomes. TMB was calculated by counting the somatic mutations, including SNVs and Indels, per megabase of the sequence examined in each patient. The variation information can be found in supplementary materials 2.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed by using SPSS version 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Fisher’s exact test was used to analyze significant differences. Bonferroni correction were performed for multiple test correction. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical statement

The project was approved by the Ethic Committee of Zhejiang Cancer Hospital. We declare that all methods used in this protocol were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. This study was approved by all patients and all participants provided informed consent.

Results

Clinical characteristics of ovarian cancer patients

A total of 65 Chinese ovarian cancer patients with a median age of 54 years (range 33–84 years) were enrolled in this study. These samples consisted of 50 (76.92%) high-grade serous adenocarcinomas, 6 (9.23%) low-grade serous adenocarcinomas, 1 (1.54%) mucinous adenocarcinoma, 1 (1.54%) clear cell tumor, 1 (1.54%) endometrioid tumor, and 6 (9.23%) unknown tumor subtypes. Forty-nine (75.38%) samples were primary lesions, and 10 (15.38%) samples were metastatic lesions. The lesion sites of 6 (9.23%) samples were unknown. According to TNM staging system, which considered the tumor size (T), lymph node/lymph node diffusion (N), and tumor metastasis (M), 5 (7.69%) patients were in stage I, 8 (12.31%) patients were in stage II, , 33 (50.77%) patients were in stage III, 9 (13.8%) patients were in stage IV, and 8 (12.31%) patients with unclear tumor stage. Histologically, 4 (6.15%) tumors were well/moderately differentiated, and 53 (81.54%) tumors were poorly/undifferentiated ovarian cancer. The differentiation information of 8 (12.31%) tumors was unknown. Patients’ clinical or pathological information was summarized and shown in Table 1.

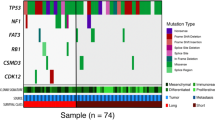

GAs in ovarian cancer

A total of 595 clinically relevant somatic GAs in 317 genes were identified by using NGS sequencing targeting 450 cancer genes and WES, with a mean of 9.15 alterations per sample (range 1–29). GAs included 285 (47.90%) SNV/ShortIndels, 263 (44.20%) CNVs, 31 (5.21%) fusions, and 16 (2.69%) LongIndels (Table S1). The most commonly mutated genes were TP53 (86.15%, 56/65), NF1 (13.85%, 9/65), NOTCH3 (10.77%, 7/65), and TERT (10.77%, 7/65) (Fig. 1). Notably, most TP53 mutations were SNVs and mainly occurred in the DNA-binding domain. In this cohort, 39 mutation sites of TP53 were detected, with the most common mutation being R273H, which was detected in 5 cases, followed by Y220C in 4 cases, and R248Q/W in 4 cases (Figure S1). Most TP53 mutations were detected once in this cohort. Although 7 GAs of TERT were detected, most of them were CNVs (Fig. 1). Germline mutations were detected in 25 of 65 OC patients, including mutations from 17 BRCA1, 3 BRCA2, 3 RAD51D, 1 RAD51C, and 1 FANCA. Except for 4 BRCA1 and 1 BRCA2 mutations which belong to SNV, the others are truncation (Table S2).

Mutational landscape of 65 ovarian cancer patients. The X-axis represents each case sample and the Y-axis represents each mutated gene. The bar graph above shows the tumor mutational burden (TMB) value of each sample, and the bar graph on the right shows the mutation frequency of each mutated gene in 65 samples. Green represents substitution/Indel mutations, red represents gene amplification mutations, blue represents gene homozygous deletion mutations, yellow represents fusion/rearrangement mutations, and purple represents truncation mutations.

Mutation characteristics of ovarian cancer patients at different ages

Patients were divided into 3 groups based on age: 32–49 years old (27.69%, 18/65), 50–59 years old (38.46%, 25/65), and 60–84 years old (33.85%, 22/65). In patients aged 32–49 years, 180 GAs from 145 genes were detected (10 GAs/patient and 8.1 genes/patient), and the most commonly mutated genes included TP53, FGFR3, MYC, and NSD2. In patients aged 50–59 years, 224 GAs from 162 genes were detected (8.96 GAs/patient and 6.48 genes/patient), and the most commonly mutated genes included TP53, NF1, BRAC1, and NOTCH3. In patients aged 60–84 years, 156 GAs from 112 genes were detected (7.1 GAs genes/patient and 5.1 genes/patient), and the most commonly mutated genes included TP53, LRP1B, CCNE1, LRP2, and NOTCH1 (Table S3).

Statistical analysis showed that the frequencies of TP53 and LRP1B mutations were significantly higher in patients aged 60–84 years compared to that in the other 2 age groups (P = 0.02 and P = 0.04, respectively), while the frequency of BRAC1 mutations was significantly higher in patients aged 50–59 years compared to the other 2 age groups (P = 0.03). Multiple comparison showed that TP53 mutation was significantly more frequent in 60–84 years group than that in 32–49 years group, and LRP1B mutation was significantly more frequent in 60–84 years group than that in 50–59 years group (Fig. 2A). Among the mutated genes with more than 2 GAs in this cohort, FGFR2 and FLI1 mutations specifically occurred in patients aged 32–49 years, FGFR1, CREBBP, NFKBIA, and RUNX1 mutations specifically occurred in patients aged 50–59 years, and LRP2, CHD4, CRLF2, EPHA3, KDM6A, KMT2C mutations specifically occurred in patients aged 60–84 years (Table S3). Although the differences of mutation frequency in each patient group were not significant, these specific gene mutations might be potential biomarkers that correlate with the age of ovarian cancer patients.

Correlated analysis of mutated genes and clinical characteristics. (A) Correlation analysis of mutated genes and the age of patients; (B) Correlation analysis of mutated genes and tumor stage; (C) Correlation analysis of mutated genes and tumor differentiation; and (D) Correlation analysis of mutated genes and TMB. The X-axis shows the mutated genes and the Y-axis represent the mutational frequency of each gene. Fisher’s exact test was used to analyze significant differences and bonferroni correction were performed for multiple test correction. ns P > 0.05, * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, and *** P < 0.001.

The mutation of BRD4 and STK11 is associated with the tumor stage of ovarian cancer

Patients were divided into 2 groups based on tumor stages: patients with stage I and stage II tumors (13 patients) and patients with stage III and stage IV (44 patients). Interestingly, we found that BRD4 and STK11 mutations were specifically detected in patients with stage I and II tumors. Statistical analysis showed that the frequency of BRD4 and STK11 mutations were significantly higher in stage I/II tumors than that in stage III/IV tumors (15.4% vs. 0%, P = 0.049, for both) (Fig. 2B).

The correlation analysis between mutated genes and tumor differentiation of ovarian cancer

Based on the tumor differentiation of ovarian cancer, we divided patients into 2 groups, patients with well/moderately differentiated tumors (4 patients) and patients with poorly/undifferentiated tumors (53 patients). In the 4 patients with well/moderately differentiated tumors, mutations of KRAS, TP53, and PTEN were detected as the most frequently mutated genes. Statistical analysis showed that the mutation frequencies of KRAS and PTEN were significantly higher in well/moderately differentiated tumors than that in poorly/undifferentiated tumors, while the mutation frequency of TP53 was significantly higher in poorly/undifferentiated tumors than that in well/moderately differentiated tumors (Fig. 2C). Although the mutation frequency of some genes, such as NF1, PRKCI, and BRCA1, were higher in the poorly/undifferentiated tumors than those in well/moderately differentiated tumors, the differences were not significant according to statistical analysis (Table S4).

GAs of ovarian cancer patients in primary and metastatic lesions

Based on the tumor lesion site, samples were divided into primary lesions and metastatic lesions. The most commonly mutated genes in 49 primary lesions were TP53, NF1, LRP2, and NTRK3, while in 10 metastatic lesions, the most commonly mutated genes were TP53, NF1, TERT, NOTCH3, and PRKCI. The mutation frequency of LRP2 and NTRK3 in metastatic tumors was higher than those in primary tumors (2% vs. 20%, P = 0.072, for both). However, due to the small number of samples, the statistical analysis results were not significant (Table 2).

The correlation between gene variations and TMB

To explore the correlation between TMB and clinically relevant GAs, we measured TMB in all samples. The median TMB of 65 samples was 4.1 muts/Mb (ranges 0.6–23.2 muts/Mb) (Table 1). Four patients were identified as high TMB (TMB-H), defined as TMB values more than 10 muts/Mb, and 54 patients were identified as low TMB (TMB-L), defined as TMB values lower than 10 muts/Mb. TMB values were not identified in 7 patients. The mutations of LRP1B, OBSCN, PIK3R2, TP53, CCNE1, LRP2, MED12, and NOTCH3 frequently occurred in patients with TMB-H, while the mutations of TP53, NF1, TERT, MYC, FAM135B, and PRKCI frequently occurred in patients with TMB-L (Table S5). Statistical analysis showed that the mutation frequencies of MED12, LRP2, PIK3R2, CCNE1, and LRP1B were significantly higher in patients with TMB-H than that in patients with TMB-L (Fig. 2D).

The molecular characteristics of high grade serous ovarian cancer patients in China are different from those in the West

Among 65 ovarian samples, 56 were serous ovarian cancer including 50 HGSOC and 6 low-grade serous ovarian cancer. The most somatic mutations were TP53 (94%), NF1 (16%), NOTCH3, PRKCI, and TERT (12%, for each), and FAM135B, MYC, NOTCH1, and PTK2 (11%, for each). According to the report from TCGA21, we compared the somatic mutational characterization of ovarian cancers between Chinese and Western. Statistical analysis showed that the mutational frequencies of NF1 (P = 0.0024), NOTCH3 (P = 0.004), PRKCI (4.49 × 10–6), TERT (4.44 × 10–7), FAM135B (0.008), MYC (4.44 × 10–7), NOTCH1 (2.71 × 10–5), and PTK2 (4.49 × 10–6) in Chinese ovarian cancer patients were significantly higher than those in Western patients (Fig. 3A). Although the mutations of BRCA1 and BRCA2 are the most common germline mutations in ovarian cancer, the mutational frequency of BRCA1 is significantly higher in Chinese than in Western (P = 0.0001), while the mutation frequency of BRCA2 is similar between them (P = 0.78) (Fig. 3B).

Different molecular characteristics of high-grade serous ovarian cancer patients in China and Western countries. (A) Differences of somatic mutations between Chinese and Western patients. (B) Differences of germline mutations between Chinese and Western patients. The X-axis shows the mutated genes and the Y-axis represents the mutational frequency of genes. Fisher’s exact test was used to analyze significant differences. ns P > 0.05, ** P < 0.01, and *** P < 0.001.

Molecular characteristics of platinum sensitive patients and their response to olaparib

Patients who relapsed more than 6 months after the last platinum chemotherapy are considered to be platinum sensitive. Six platinum sensitive patients were treated with olaparib at the recommended dose of 200 mg twice a day. Five of them (case 1–5) responded well and one (case 6) failed to response. To understand the molecular feature of these patients, WES was performed for further mutated gene detection. The most frequent mutated gene of 6 cases were TP53, AURKA, ITK, NOTCH3, RECQL4, and BRCA1 and the other 110 mutated genes were detected only once (Fig. 4, Table S6). We found that only case 2 harbored the mutation of BRCA1 rearrangement, the amplifications of AURKA and RAD21 were detected in case 1, and AURKA SNV was detected in case 3. Most of mutations in case 1 were gene amplification, while most of mutations in other cases were SNV. In addition to SNV and gene amplification mutations, deletion of PARK2, QKI, GATA4, PML, PRKAR1A, and LRP1B were detected in case 6 (Table S6).

Discussion

Ovarian cancer is a heterogeneous disease in morphology and biology. Effectively identifying gene variations is of great importance to personalized medicine and determining potential therapeutic targets for ovarian cancer. NGS technology is a potentially effective method for identifying subgroups of patients based on their genomic characteristics. Here, we identified the mutational profile of 65 ovarian cancer samples, most of which were HGSOC. Consistent with previous studies, TP53 was also the most frequently detected gene mutation9,10,11. TP53 is a well-known tumor suppressor gene which can regulate key transcription factors of DNA repair, apoptosis, aging, and stress metabolism22. The mutation of TP53 may lead to inactivation of the p53 pathway and activation of multiple carcinogenic pathways23. The mutations of TP53 can be classified as gain-of-function or loss-of-function24,25. Previously, Garziera et al. successfully identified 6 new mutation sites of TP53 in HGSOC patients by using NGS26. Although 38 mutation sites of TP53 were detected in this cohort, none of them were the same. These results indicate that TP53 variants are complex and each mutation site that was detected might be a potential target for further therapy. A high frequency of TP53 mutations was associated with a poor prognosis in many cancers, including HGSOC27. A TP53 mutation frequency of more than 80% was detected in this cohort and may suggest a poor prognosis of ovarian cancer patients. In addition to TP53 mutations, KRAS, PIK3CA, PTEN, and BRCA1 mutations were also commonly detected in ovarian cancer10,28. However, a lower mutation frequency of KRAS, PIK3CA, and BRCA1 was detected in this cohort, which may be due to most patients having HGSOC.

Patients’ age, tumor stage, and histological subtype are the most important prognostic factors29. Based on 104 patients with epithelial ovarian cancer, Ashour et al. showed that 86.4% of patients harboring BRCA1/2 mutations were younger than 50 years old, suggesting that the age at diagnosis was a strong predictor of the presence of pathogenic BRCA1/2 mutations30. In another study of stage II-IV high-grade epithelial ovarian cancer, deleterious germline BRCA mutations were detected and patients’ mean age at diagnosis was younger for patients harboring BRCA1 mutations than patients harboring BRCA2 mutations (52 years vs. 57 years, respectively, P = 0.06)31. Zhu et al. showed that serous ovarian cancer had a significantly higher BRCA1 hypermethylation frequency compared to non-serous ovarian cancer, but there was no significant correlation between BRCA1 hypermethylation and age32. Consistent with previous studies, we also found that BRCA1 mutations occurred with a higher frequency in the younger age group, but there was no significant difference between each age group. Notably, a high frequency of TP53 mutations occurred in older patients in this cohort, suggesting a worse prognosis for older patients.

LRP1B is a tumor suppressor that interacts with uPAR to inhibit cell migration33. LRP1B was reported to be a potential factor for chemoresistance in HGSOC patients34. Similar to TP53 mutations, the mutation of LRP1B also implies a poor prognosis in older ovarian cancer patients. In this study, we detected a high frequency of LRP1B mutations in older ovarian cancer patients. Together, our results supported that TP53, LRP1B, and BRCA1 were potential biomarkers for ovarian cancer patients. However, a shortcoming of this study was the small number of samples, and whether or not FGFR1 and LRP2 mutations specifically occurred in certain age groups still needs to be further confirmed with a larger patient cohort. We analyzed the mutations of BRD4 and STK11 from TCGA database and found that the mutation frequency of these two genes was (0.6%, 2/316)21. In this study, the mutation frequency of these two genes were 3% (2 / 65). Although the mutations of BRD4 and STK11 were associated with tumor stage in this study, the low frequency of BRD4 and STK11 mutations suggests that the sample population may be too small to cause false positive. Further studies with large population are needed to confirm this.

KRAS encodes a small GTPase and functions in many cellular processes by regulating its downstream pathways35. KRAS mutations have been considered as a biomarker for a more increased risk of ovarian cancer36, and its mutation status could also be a predictor for MEK inhibitor sensitivity in ovarian cancer37. PTEN is a tumor suppressor that regulates phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) signals38. Many studies have reported the importance of PTEN in ovarian cancer. Loss of PTEN may lead to a poor response to bortezomib in advanced ovarian cancer patients39, and the expression of PTEN was reported to be a prognosis biomarker in ovarian cancer40. Both KRAS and PTEN mutations commonly occurred in ovarian cancer10. Interestingly, even though only 4 cases with well/moderately differentiated tumors, we detected a correlation between TP53, KRAS, and PTEN mutations and tumor differentiation. This result supported that TP53, KRAS, and PTEN could be potential biomarkers as prognostic predictors of ovarian cancer. However, further confirmation is still needed. Tumor differentiation is associated with prognosis. Poorly differentiated tumors usually indicate a poor prognosis and well-differentiated tumors are more likely to indicate a good prognosis41. Su et al. reported that the high expression of miR-23a and the low expression of miR-23b were not only associated with medium/high differentiated tumors, but were also associated with the poor prognosis of ovarian cancer patients42. Combined with the correlation between the mutations of TP53, KRAS, and PTEN and tumor differentiation of ovarian cancer, it supports that tumor differentiation might be positively associated with prognosis in ovarian cancer.

Tumor heterogeneity is mainly due to the production of clones with metastatic potential and the existence of drug resistant mutations43. Metastasis is the main cause of malignant transformation and death for most cancer patients44. A large number of ovarian cancer patients develop widespread cancer cells beyond the ovaries or distant metastasis45. Biomarkers of biological targets that are associated with ovarian cancer metastasis have been widely researched. Zhao et al. found that STAT4 is a key regulator of ovarian cancer metastasis46. Wang et al. reported that the expression of MTA1 was reported to be associated with metastasis of ovarian cancer47. Grither et al. reported that discoidin domain receptor 2 (DDR2), a receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK), is a potential target for the treatment of metastatic ovarian cancer48. In this study, although no significant correlation between mutated genes and tumor metastasis was detected, high mutational frequencies of LRP2 and NTRK3 were detected in metastatic tumors. NTRK3 had been reported to be a prognosis predictor of ovarian cancer based on the correlation between NTRK3 CNVs and platinum-sensitive and platinum-resistant recurrences49. Festuccia et al. also reported that CEP-701, a pan TRK inhibitor, could effectively reduce metastasis in advanced prostate cancer50. Recently, Tian et al. explained that LRP2 played an important role in tumor cell motility and the tumor metastasis mechanism regulated by Hsp90α51. All these studies support our conclusion from this study that NTRK3 and LRP2 might be prognosis biomarkers for Chinese ovarian cancer patients.

Wang et al. investigated the molecular profiles and analyzed TMB in Chinese patients with gynecological cancers, including ovarian, cervical, and endometrial cancers, and found that the mutation of BRCA1 was associated with higher TMB in ovarian cancer patients52. Birkbak et al. studied TMB in ovarian cancer with BRCA1 and BRCA2 and found that TMB coupled with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations could be used as a genomic marker of prognosis and a predictor of treatment response53. Although most BRCA1/2 mutations occurred in the TMB-L group, we did not detect a correlation between BRCA1/2 mutations and TMB in this study, which might be due to the small number of patients in this cohort. However, correlations between the mutations of MED12, LRP2, PIK3R2, CCNE1, and LRP1B and TMB-H were detected. TMB-H has been reported to correlate with the generation of neoantigens and potential clinical responses to immunotherapies in many cancer types54,55. A case report of a 71-year-old female with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer also showed that TMB might be a biomarker for immunotherapy56. Together, we deduced that MED12, LRP2, PIK3R2, CCNE1, and LRP1B might be potential biomarkers for immunotherapy of ovarian cancer.

Previous studies showed that 96% of ovarian cancer patients had TP53 mutation, while the frequencies of other mutations were less than 10%21. In this study, in addition to the high frequency TP53 mutations, we also identified a series of somatic mutations such as NF1, NOTCH3, PRKCI, TERT, FAM135B, MYC, NOTCH1, and PTK2, which were high frequently occurred and significantly higher in Chinese than those in Western patients, suggesting different mutational patterns of Chinese and Western patients. The high frequency mutations in this cohort means that Chinese ovarian cancer patients may share more common mutation, which is of great significance for the development of targeted treatment and precise treatment for further ovarian cancer treatment. The common germline mutations in ovarian cancer includes BRCA1, BRCA2, ATM, MSH3 and PALB257. The most common germline mutations are BRCA1 and BRCA257. In this study, we identified 25 germline mutations from 25 patients. Interestingly, the frequency of BRCA1 germline mutations in Chinese is significantly higher than that in Western ovarian cancer patients, which also supported the different mutational patterns of ovarian cancer patients in different regions. Other germline mutations, such as BRCA2, RAD51D, RAD51C, and FANCA, were also identified in this study. They are all associated with homologous recombination deficiency (HRD)58, suggesting that nearly half of Chinese ovarian patients may benefit from Polyadenosine-diphosphate-ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors.

PARP inhibitors were considered to improve progression-free survival (PFS) of platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer patients59,60. In this study, we identified the mutations of six platinum sensitive patients who were received olaparib treatment. Interestingly, BRCA1 rearrangement was found in an olaparib benefited patient. The BRCA mutations in response to PAPR inhibitors is complex. So far, few studies had reported that BRCA1 rearrangement in ovarian cancer was responsive to olaparib. Our result suggested that patients with BRCA rearrangement might also be sensitive to olaparib. Meanwhile, we also found the amplification of AURKA and RAD21 and SNV mutation of AURKA in 2 olaparib benefited patients. Both AURKA and RAD21 were reported to relate with DNA repair system, and so that considered as HRD genes61,62. Many studies have shown that ovarian cancer patients with HRD related mutations were a target for PARP inhibitors63. However, both BRCA mutations and reported HRD related mutations failed to detected in two patients who benefits from olaparib in this study. This may be due to other mechanisms and further research is needed. Interestingly, we found deletions of GATA4 and LRP1B in a patient who failed to response to olaparib. GATA4 and LRP1B were tumor suppressor genes32,64, which might be related to the resistance of olaparib. However, only one patient tested is not enough to support this deduce, and more relevant cases still needed for further research.

In conclusion, we identified the genomic landscape of Chinese ovarian cancer patients and identified the correlation between mutated genes and clinical features including patients’ age, tumor differentiation, tumor lesion site, and TMB value. A series of potential biomarkers were identified for the prognosis of ovarian cancer patients. Our results supported that olaparib is effective in platinum sensitive patients with BRCA mutation and HRD related mutations. Although we had a limited number of samples, our study has enriched the understanding of the genomic mutational features of ovarian cancer and provides a basis for further development and application of molecular targeted therapy for ovarian cancer patients.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Stewart, C., Ralyea, C. & Lockwood, S. Ovarian cancer: an integrated review. Semin. Oncol. Nurs. 35, 151–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soncn.2019.02.001 (2019).

Jemal, A., Siegel, R., Xu, J. & Ward, E. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J. Clin. 60, 277–300. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.20073 (2010).

Chien, J. & Poole, E. M. Ovarian cancer prevention, screening, and early detection: report from the 11th biennial ovarian cancer research symposium. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer Off. J. Int. Gynecol. Cancer Soc. 27, S20-s22. https://doi.org/10.1097/igc.0000000000001118 (2017).

Jayson, G. C., Kohn, E. C., Kitchener, H. C. & Ledermann, J. A. Ovarian cancer. Lancet (London, England) 384, 1376–1388. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(13)62146-7 (2014).

Monk, B. J. & Coleman, R. L. Changing the paradigm in the treatment of platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer: from platinum doublets to nonplatinum doublets and adding antiangiogenesis compounds. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer Off. J. Int. Gynecol. Cancer Soc. 19(Suppl 2), S63-67. https://doi.org/10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181c104fa (2009).

Groisberg, R., Roszik, J., Conley, A., Patel, S. R. & Subbiah, V. The role of next-generation sequencing in sarcomas: evolution from light microscope to molecular microscope. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 19, 78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11912-017-0641-2 (2017).

Kamps, R. et al. Next-generation sequencing in oncology: genetic diagnosis, risk prediction and cancer classification. Int. J. Mol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms18020308 (2017).

Imperial, R. et al. Matched whole-genome sequencing (WGS) and whole-exome sequencing (WES) of tumor tissue with circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) analysis: complementary modalities in clinical practice. Cancers https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers11091399 (2019).

Li, C. et al. Mutational landscape of primary, metastatic, and recurrent ovarian cancer reveals c-MYC gains as potential target for BET inhibitors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 116, 619–624. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1814027116 (2019).

Balendran, S. et al. Next-Generation Sequencing-based genomic profiling of brain metastases of primary ovarian cancer identifies high number of BRCA-mutations. J. Neurooncol. 133, 469–476. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-017-2459-z (2017).

Li, W. et al. Germline and somatic mutations of multi-gene panel in Chinese patients with epithelial ovarian cancer: a prospective cohort study. J. Ovar. Res. 12, 80. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13048-019-0560-y (2019).

Risch, H. A., Marrett, L. D., Jain, M. & Howe, G. R. Differences in risk factors for epithelial ovarian cancer by histologic type. Results of a case-control study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 144, 363–372. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008937 (1996).

Fortner, R. T. et al. Reproductive and hormone-related risk factors for epithelial ovarian cancer by histologic pathways, invasiveness and histologic subtypes: results from the EPIC cohort. Int. J. Cancer 137, 1196–1208. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.29471 (2015).

Prat, J. & Mutch, D. G. Pathology of cancers of the female genital tract including molecular pathology. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. Off. Organ Int. Feder. Gynaecol. Obstetr. 143(Suppl 2), 93–108. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.12617 (2018).

Garziera, M. et al. New challenges in tumor mutation heterogeneity in advanced ovarian cancer by a targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS) approach. Cells https://doi.org/10.3390/cells8060584 (2019).

Ow, G. S., Ivshina, A. V., Fuentes, G. & Kuznetsov, V. A. Identification of two poorly prognosed ovarian carcinoma subtypes associated with CHEK2 germ-line mutation and non-CHEK2 somatic mutation gene signatures. Cell cycle (Georgetown, Tex) 13, 2262–2280. https://doi.org/10.4161/cc.29271 (2014).

Kuo, K. T. et al. Analysis of DNA copy number alterations in ovarian serous tumors identifies new molecular genetic changes in low-grade and high-grade carcinomas. Can. Res. 69, 4036–4042. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.can-08-3913 (2009).

Ganapathi, M. K. et al. Expression profile of COL2A1 and the pseudogene SLC6A10P predicts tumor recurrence in high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Int. J. Cancer 138, 679–688. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.29815 (2016).

Cao, J. et al. An accurate and comprehensive clinical sequencing assay for cancer targeted and immunotherapies. Oncologist 24, e1294–e1302. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2019-0236 (2019).

Tian, W. et al. Comprehensive genomic profile of cholangiocarcinomas in China. Oncol. Lett. 19, 3101–3110. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2020.11429 (2020).

Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature 474, 609–615. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10166 (2011).

Freed-Pastor, W. A. & Prives, C. Mutant p53: one name, many proteins. Genes Dev. 26, 1268–1286. https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.190678.112 (2012).

Bykov, V. J. N., Eriksson, S. E., Bianchi, J. & Wiman, K. G. Targeting mutant p53 for efficient cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 18, 89–102. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc.2017.109 (2018).

Brachova, P., Thiel, K. W. & Leslie, K. K. The consequence of oncomorphic TP53 mutations in ovarian cancer. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 14, 19257–19275. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms140919257 (2013).

Brachova, P. et al. TP53 oncomorphic mutations predict resistance to platinum and taxanebased standard chemotherapy in patients diagnosed with advanced serous ovarian carcinoma. Int. J. Oncol. 46, 607–618. https://doi.org/10.3892/ijo.2014.2747 (2015).

Garziera, M. et al. Identification of Novel Somatic TP53 Mutations in Patients with High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer (HGSOC) Using Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS). Int. J. Mol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms19051510 (2018).

Bowtell, D. D. The genesis and evolution of high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 10, 803–808. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc2946 (2010).

Gockley, A. et al. Outcomes of women with high-grade and low-grade advanced-stage serous epithelial ovarian cancer. Obstet. Gynecol. 129, 439–447. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0000000000001867 (2017).

Cannistra, S. A. Cancer of the ovary. N. Engl. J. Med. 351, 2519–2529. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra041842 (2004).

Ashour, M. & Ezzat Shafik, H. Frequency of germline mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 in ovarian cancer patients and their effect on treatment outcome. Cancer Manag. Res. 11, 6275–6284. https://doi.org/10.2147/cmar.s206817 (2019).

Jorge, S. et al. Patterns and duration of primary and recurrent treatment in ovarian cancer patients with germline BRCA mutations. Gynecol. Oncol. Rep. 29, 113–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gore.2019.08.001 (2019).

Zhu, X., Zhao, L. & Lang, J. The BRCA1 methylation and PD-L1 expression in sporadic ovarian cancer. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer Off. J. Int. Gynecol. Cancer Soc. 28, 1514–1519. https://doi.org/10.1097/igc.0000000000001334 (2018).

Li, Y. et al. Low density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor-related protein 1B impairs urokinase receptor regeneration on the cell surface and inhibits cell migration. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 42366–42371. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M207705200 (2002).

Cowin, P. A. et al. LRP1B deletion in high-grade serous ovarian cancers is associated with acquired chemotherapy resistance to liposomal doxorubicin. Can. Res. 72, 4060–4073. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.can-12-0203 (2012).

Karnoub, A. E. & Weinberg, R. A. Ras oncogenes: split personalities. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 517–531. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrm2438 (2008).

Keane, F. K. & Ratner, E. S. The KRAS-variant genetic test as a marker of increased risk of ovarian cancer. Rev. Obstet. Gynecol. 3, 118–121 (2010).

Nakayama, N. et al. KRAS or BRAF mutation status is a useful predictor of sensitivity to MEK inhibition in ovarian cancer. Br. J. Cancer 99, 2020–2028. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.bjc.6604783 (2008).

Miller, T. W. et al. Loss of Phosphatase and Tensin homologue deleted on chromosome 10 engages ErbB3 and insulin-like growth factor-I receptor signaling to promote antiestrogen resistance in breast cancer. Can. Res. 69, 4192–4201. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.can-09-0042 (2009).

Chui, M. H. et al. Chromosomal instability and mTORC1 activation through PTEN loss contribute to proteotoxic stress in ovarian carcinoma. Can. Res. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.can-18-3029 (2019).

Shen, W., Li, H. L., Liu, L. & Cheng, J. X. Expression levels of PTEN, HIF-1alpha, and VEGF as prognostic factors in ovarian cancer. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 21, 2596–2603 (2017).

Shen, J. et al. The impact of tumor differentiation on the prognosis of HBV-associated solitary hepatocellular carcinoma following hepatectomy: a propensity score matching analysis. Dig. Dis. Sci. 63, 1962–1969. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-018-5077-5 (2018).

Su, L. & Liu, M. Correlation analysis on the expression levels of microRNA-23a and microRNA-23b and the incidence and prognosis of ovarian cancer. Oncol. Lett. 16, 262–266. https://doi.org/10.3892/ol.2018.8669 (2018).

Dexter, D. L. & Leith, J. T. Tumor heterogeneity and drug resistance. J. Clin. Oncol. Off. J. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. 4, 244–257. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.1986.4.2.244 (1986).

Pantel, K. & Brakenhoff, R. H. Dissecting the metastatic cascade. Nat. Rev. Cancer 4, 448–456. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc1370 (2004).

Russell, M. R. et al. Novel risk models for early detection and screening of ovarian cancer. Oncotarget 8, 785–797. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.13648 (2017).

Zhao, L. et al. An integrated analysis identifies STAT4 as a key regulator of ovarian cancer metastasis. Oncogene 36, 3384–3396. https://doi.org/10.1038/onc.2016.487 (2017).

Wang, X. et al. MicroRNA-30c inhibits metastasis of ovarian cancer by targeting metastasis-associated gene 1. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 13, 676–682. https://doi.org/10.4103/jcrt.JCRT_132_17 (2017).

Grither, W. R. et al. TWIST1 induces expression of discoidin domain receptor 2 to promote ovarian cancer metastasis. Oncogene 37, 1714–1729. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41388-017-0043-9 (2018).

Ge, L. et al. Copy number variations of neurotrophic tyrosine receptor kinase 3 (NTRK3) may predict prognosis of ovarian cancer. Medicine 96, e7621. https://doi.org/10.1097/md.0000000000007621 (2017).

Festuccia, C. et al. Tyrosine kinase inhibitor CEP-701 blocks the NTRK1/NGF receptor and limits the invasive capability of prostate cancer cells in vitro. Int. J. Oncol. 30, 193–200 (2007).

Tian, Y. et al. Extracellular Hsp90alpha and clusterin synergistically promote breast cancer epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and metastasis via LRP1. J. Cell Sci. https://doi.org/10.1242/jcs.228213 (2019).

Wang, M. et al. Molecular profiles and tumor mutational burden analysis in Chinese patients with gynecologic cancers. Sci. Rep. 8, 8990. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-25583-6 (2018).

Birkbak, N. J. et al. Tumor mutation burden forecasts outcome in ovarian cancer with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations. PLoS ONE 8, e80023. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0080023 (2013).

Yuza, K., Nagahashi, M., Watanabe, S., Takabe, K. & Wakai, T. Hypermutation and microsatellite instability in gastrointestinal cancers. Oncotarget 8, 112103–112115. https://doi.org/10.18632/oncotarget.22783 (2017).

Chalmers, Z. R. et al. Analysis of 100,000 human cancer genomes reveals the landscape of tumor mutational burden. Genome Med. 9, 34. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13073-017-0424-2 (2017).

Morse, C. B., Elvin, J. A., Gay, L. M. & Liao, J. B. Elevated tumor mutational burden and prolonged clinical response to anti-PD-L1 antibody in platinum-resistant recurrent ovarian cancer. Gynecol. Oncol. Rep. 21, 78–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gore.2017.06.013 (2017).

Kanchi, K. L. et al. Integrated analysis of germline and somatic variants in ovarian cancer. Nat. Commun. 5, 3156. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms4156 (2014).

Heeke, A. L. et al. Actionable co-alterations in breast tumors with pathogenic mutations in the homologous recombination DNA damage repair pathway. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-020-05849-2 (2020).

Pujade-Lauraine, E. et al. Olaparib tablets as maintenance therapy in patients with platinum-sensitive, relapsed ovarian cancer and a BRCA1/2 mutation (SOLO2/ENGOT-Ov21): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 18, 1274–1284. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1470-2045(17)30469-2 (2017).

Moore, K. et al. Maintenance olaparib in patients with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 379, 2495–2505. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1810858 (2018).

Guacci, V. Sister chromatid cohesion: the cohesin cleavage model does not ring true. Genes Cells Devoted Mol. Cell. Mech. 12, 693–708. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2443.2007.01093.x (2007).

Blanco, I. et al. Assessing associations between the AURKA-HMMR-TPX2-TUBG1 functional module and breast cancer risk in BRCA1/2 mutation carriers. PLoS ONE 10, e0120020. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0120020 (2015).

Ledermann, J. A., Drew, Y. & Kristeleit, R. S. Homologous recombination deficiency and ovarian cancer. Eur. J. Cancer (Oxford, England: 1990) 60, 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2016.03.005 (2016).

Gao, L. et al. Lung cancer deficient in the tumor suppressor GATA4 is sensitive to TGFBR1 inhibition. Nat. Commun. 10, 1665. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-09295-7 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by Medical Health Science and Technology Project of Zhejiang Provincial Health Commission (No. 2020383253) and Social Development Project of Public Welfare Technology Research in Zhejiang Province (NO. LGF21H160008).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.Z., Y.Z., and X.C. collected patient consents and samples and analyzed data; X.S., P.Z. and A.L. contributed to bioinformatics analysis and wrote the manuscript; T.Z. designed and supervised the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Y., Shi, X., Zhang, J. et al. A comprehensive analysis of somatic alterations in Chinese ovarian cancer patients. Sci Rep 11, 387 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-79694-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-79694-0

This article is cited by

-

An integrated machine learning-based model for joint diagnosis of ovarian cancer with multiple test indicators

Journal of Ovarian Research (2024)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.