Abstract

Cross-sectional observations have shown that the timing of eating may be important for health-related outcomes. Here we examined the stability of eating timing, using both clock hour and relative circadian time, across one semester (n = 14) at daily and monthly time-scales. At three time points ~ 1 month apart, circadian phase was determined during an overnight in-laboratory visit and eating was photographically recorded for one week to assess timing and composition. Day-to-day stability was measured using the Composite Phase Deviation (deviation from a perfectly regular pattern) and intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) were used to determine individual stability across months (weekly average compared across months). Day-to-day clock timing of caloric events had poor stability within individuals (~ 3-h variation; ICC = 0.12–0.34). The timing of eating was stable across months (~ 1-h variation, ICCs ranging from 0.54–0.63), but less stable across months when measured relative to circadian timing (ICC = 0.33–0.41). Our findings suggest that though day-to-day variability in the timing of eating has poor stability, the timing of eating measured for a week is stable across months within individuals. This indicates two relevant timescales: a monthly timescale with more stability in eating timing than a daily timescale. Thus, a single day’s food documentation may not represent habitual (longer timescale) patterns.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Weight gain and obesity rates have continued to rise globally1,2, despite the efforts of public health initiatives designed to combat this epidemic3. College-aged individuals have the highest rates of increased weight gain compared to the general population or any other age group4,5,6. Weight gain during this time may have major public health implications as college is a critical developmental time for establishing long-term health behaviors7,8. As overweight or obese adolescents have double the risk for high weight status in adulthood9, identification of mechanisms and behaviors by which college students are vulnerable to weight gain, and thus could be targeted by countermeasures, is imperative to combat this global obesity epidemic.

Mounting evidence suggests that the timing of eating plays an important role in cardiometabolic health10,11,12,13,14,15. We have shown that, relative to lean individuals, non-lean individuals consume the majority of their daily calories later, specifically closer to their dim-light melatonin onset (DLMO), a circadian phase marker denoting the start of a person’s biological night16,17. Other reports have also found relationships between later eating and weight gain18 and higher body mass index19. However, these observations of the timing of eating and poor health have come from short, cross-sectional protocols using clock time (which is not a physiological variable) as the reference point. The reliability of cross-sectional studies of meal timing, and more specifically the circadian timing (i.e., a physiological variable) of caloric intake, to accurately reflect the timing of eating has been largely unexplored.

The stability of meal intake (in addition to its timing) has also been hypothesized to play a role in cardiometabolic health20. Often, meal stability is discussed as the regular consumption (or skipping) and size of specified meals (breakfast, lunch, dinner, and snacks) or the number of meals, across multiple days. In these cases, less stable patterns of eating timing have been shown to be associated with poorer cardiometabolic health20,21,22. These reports20,21,22 on meal stability are also limited in that stability is typically examined only across several days within a week, and not multiple time-points further apart. By measuring regularity as either consuming or not consuming a meal, rather than examining day-to-day stability in the timing of caloric events (defined as any time calories are consumed > 15 min apart16,23,24), as we have previously done using day-to-day stability of sleep metrics25, important information regarding stability may be overlooked.

We examined the stability of the timing of food consumption, referenced to both clock time and relative to circadian time, at three time points across a semester in college undergraduates both for all individuals and for lean vs non-lean group. Specifically, we tested the hypotheses that (i) the timing of food consumption would be stable across multiple months, and (ii) the physiologically-based circadian timing of food consumption would be more stable than clock timing of food consumption. Additionally, we tested the exploratory hypotheses that (iii) individuals with a lean body composition would have more stable timing of food consumption and number of daily calories per month compared to non-lean individuals. It is critical to understand these relationships in order to determine whether results from cross-sectional studies can be meaningfully extrapolated into potential predictors for disease or used in countermeasures to combat poor health and disease, and encourage healthy eating behaviors.

Materials and methods

Participants

Participants (n = 15) were studied during one spring semester at one US university. One lean participant (male) did not complete any meal diaries and was excluded from the analyses; thus 14 individuals (5 female), aged 19.1 years (± standard error of mean (SEM), range; 0.3, 18–21) with an average body mass index of 22.9 kg/m2 (0.8, 18.3–28.5), were studied. To be eligible, participants needed to: have a device capable of downloading the food tracking application; not be currently employed in night shift work; and not have traveled more than one time zone in the 3 months prior to and during the protocol. Study procedures were approved at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital by the Partner’s Healthcare Institutional Review Board (#2012P001631) and performed in accordance to the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided written informed consent. This trial was registered at clinicaltrials.gov as NCT02846077. Note, only a subset of participants from the overall trial partook in this semester-long study, and no participants or their data from previous publications16,17,25 were used in the current study.

Field study procedures

To track meals throughout the three separate occasions across the protocol, participants used the photographic mobile phone application MealLogger (Wellness Foundry, New York, NY) for 7-consecutive days (including both school/work and free days). Each food monitoring week occurred near the time of each in-laboratory visit; none occurred during the in-laboratory visit and it was random as to whether it occurred before or after the visit and day of the week that it started. All food monitoring weeks occurred when participants were at school; none was a vacation week. The food monitoring app allowed participants to take a time-stamped photograph of all food and beverages consumed, label what meal was being consumed (breakfast, lunch, dinner, snack, or beverage) and write a detailed description of the meal content (i.e., any ingredients or foodstuffs unable to be identified from the photo)16,17. Participants were asked to include an object of known size within the picture to help calculate portion size and to take a second photo if the meal was not fully consumed to estimate total caloric intake. After participants had uploaded the picture and description of their meals, the photos were available to study nutritionists and study staff for scoring of timing of meal, caloric content, and macronutrient composition. Participants were also able to take a picture for later upload if out of internet range or cell-service at the time of the meal. If any aspect of the photo was unclear, or if the participant documented ≤ 2 meals within a waking day, staff followed up with participants via email or through the mobile app within 24 h after upload.

In-laboratory procedures

Participants were admitted to the Brigham and Women’s Hospital Center for Clinical Investigation and Intensive Physiologic Monitoring Unit at the beginning, middle, and end of semester (i.e., three separate occasions) for an approximate 16-h overnight stay to assess DLMO timing as a marker of circadian timing and to determine body composition. Beginning at ~ 15:30 h, ambient lighting was lowered to dim settings (~ 4 lx) and saliva samples were collected hourly beginning at ~ 16:00 h and ending at ~ 07:00 h (16 samples per participant) and later assayed for melatonin. Upon admission, participants were not allowed to use any personal light-emitting electronic devices, and were instructed to refrain from eating or drinking and to maintain a constant seated posture for 20 min immediately prior to each saliva sample collection, to minimize any potential exogenous influences on melatonin concentrations. At all other times during the protocol, participants were able to eat a provided snack, ambulate within the study room, remain seated, or sleep in a seated position. If participants slept, they were awakened by research staff immediately prior to saliva collection.

During each visit to the laboratory, participants also had their body composition measured via four-lead bioelectrical impedance (Quantum II BIA analyzer, RJL Systems, Clinton Township, MI); all metals and devices were removed and measurements were conducted on participants in the supine position. Impedance measurements were performed three times per visit and an average impedance score of the three measures per visit was used for analysis.

Analysis

DLMO was determined as the linear interpolated point in time at which melatonin concentrations crossed and remained above a 5 pg/ml threshold26. All caloric events were assigned a circadian phase relative to the timing of each participant’s DLMO (which was assigned 0°).

The timing of each caloric event record was reviewed within 24 h of entry and double checked for accuracy by a second staff member. Caloric content and macronutrient compositions of each entry were independently scored by two research dieticians within the Brigham and Women’s Hospital Center for Clinical Investigation using the University of Minnesota Nutrition Data System for Research software27,28. Any caloric event that was recorded ≤ 15 min of a previous event and labeled as the same type of meal (e.g., lunch) was combined with the previous entry into one ‘caloric event’16,23. The caloric midpoint was calculated as the time at which 50% of each individuals’ daily calories were consumed16 and peak calories as the circadian phase each day in which participants consumed their highest caloric intake, both measured daily and averaged across each week.

To assess day-to-day stability of meal timing, the Composite Phase Deviation (CPD) metric was applied to the first, midpoint, and last daily caloric event. The CPD combines two components: (i) how different meal timing is compared to that on the previous day (regularity component) and (ii) how far away it is from the daily mean (alignment component)29. CPD scores reflect the average deviation in hours from a perfectly regular pattern of meal timing (i.e., same time every day).

where DD stands for “day-to-day”, AT for “average timing”, and i denotes a given day and N the total number of days. The metric was originally developed for sleep timing but has been previously applied to the daily timing of social events25. We also computed the standard deviation of first, midpoint, and last caloric event for each individual for each week of measurement.

In order to account for physiological sex differences in body fat compositions, sex-dependent criteria were used to separate participants into lean (n = 8, 1 female) or non-lean (n = 6, 4 female) body composition groups. Non-lean participants were defined as an average body fat percentage across the three in-lab visits ≥ 31% for females and ≥ 21% for males30; lean participants had an average body fat percentage below those criteria.

All variables were first analyzed using mixed-effects models (variance components) with month (each individuals’ 7-day monitoring average within month 1, 2, or 3) as a categorical fixed factor and participant as a random factor to determine group differences across months. If a main effect was present, planned comparison dependent t-tests were used to determine differences between months and Bonferroni corrections were applied (p < 0.017 needed to reach significance) to correct for multiple comparisons. To examine individual consistency of each variable within a participant across measurement months, intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC) were used to determine the stability of individual differences across months for a single score, two-way mixed-effects model31. The strength of ICC scores were defined using the following criteria: slight (0.00–0.20), fair (0.21–0.40), moderate (0.41–0.60), substantial (0.61–0.80), and almost perfect (0.81–1.00)32. Relationships between months were also analyzed using Pearson correlations after being measured for normality using skewness and kurtosis metrics. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

On average, participants were studied across 104 days (overall 3-month average ± SEM, range for 3 months; 2.4, 80–112 days) during the semester. Data collection (identified as Months 1–3) occurred at weeks 2–6 (month 1), 7–11 (month 2), and 12–16 after start of overall study (month 3). Across the semester, average overall DLMO timing was 23:26 (0:29, 20:06–03:32), which did not significantly differ between months (Table 1). To explore the relationship between the stability of metrics and body composition, we analyzed the associations between months in individuals separated into lean (n = 8) and non-lean (n = 6) categories based on sex-specific body fat percentage criteria30. To first understand whether differences in melatonin stability were driven by body composition, we tested the relationship between DLMO timing between months in each group. We found a significant positive association in DLMO timing in the non-lean group between month 1 and 2 (r = 0.94, p < 0.01) and in both lean (r = 0.9, p = 0.04) and non-lean (r = 0.93, p < 0.01) groups between months 1 and 3; there were no significant associations between month 1 and 2 in the lean group (r = 0.78, p = 0.07).

Day-to-day variability in timing of eating

To compute day-to-day variability in the timing of food consumption, we applied the CPD (i.e., average deviation in hours from a perfectly regular pattern of meal timing) and calculated standard deviation for the first, midpoint, and last daily caloric events for each participant every day within each week. In general, across the duration of study, the CPD for the first daily caloric event was 3.1 h (0.4, 0.8–5.3), midpoint was 3.7 h (0.4, 1.2–5.5), and last was 4.9 h (0.3, 3.0–6.7), whereas standard deviations were 2.2 h (0.2, 0.2–5.1), 3.5 h (0.2,1.1–6.0) and 2.6 h (0.2, 0.4–5.7), respectively; there were no significant main effects for month for any CPD or standard deviation metric (all p > 0.36, Table 1). CPD metrics were relatively inconsistent within participants across months, with ICC values ranging from slight (ICC = 0.12 and 0.13 for first daily caloric event and caloric midpoint, respectively) to fair (ICC = 0.34 for last daily caloric event) in strength. Standard deviations ranged from slight (ICC = 0.18 for caloric midpoint) to moderate (ICC = 0.43 for both first and last daily caloric events). There was a significant positive association in the CPD for first daily caloric event and standard deviation of caloric midpoint between months 1 and 3 in the lean group (r = 0.96, p < 0.01; r = 0.95, p < 0.05), but no significant relationships between months in any other CPD or standard deviation metric for either lean (all p > 0.12) or non-lean (all p > 0.11) groups.

Stability of eating behaviors by clock timing

To determine the stability of eating timing across months, data were analyzed using mixed-effects models across months. At this population level, there were no significant effects of month across the study in weekly timing of participant-identified breakfast, lunch, or dinner; there was a significant main effect of month for snacks (Table 1). The variation across months was ~ 1 h (in comparison to the ~ 3 h day-to-day variation detailed above). Planned comparisons of snack timing did not reveal any significant differences between specific months (all p > 0.06). There was overlap in the timing of breakfast and lunch meals, and of snack meals and all other meals. We also calculated the weekly average group timing of the first daily caloric event, the time at which 50% of daily calories were consumed (i.e., caloric midpoint), and the last daily caloric event. There was a significant main effect of month for the timing of the first daily caloric event, but not the caloric midpoint or the last daily caloric event (Table 1), with the first caloric event significantly earlier during month 1 versus month 2 (p < 0.01).

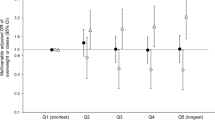

At the individual level across the three months, participants were least consistent in the timing of breakfast and lunch (ICC score of fair relationship strength), more consistent in snack timing (moderate relationship strength), and most consistent in dinner timing (substantial relationship strength) (Fig. 1). Participants tended to be more individually consistent in the timing of the first (substantial relationship strength), than in the midpoint and last caloric event (both moderate relationship strengths) (Fig. 2a–c).

Individual differences in breakfast (a), lunch (b), dinner (c) and snacks (d) timing during three different months across the semester. Participants are ordered from earlier to later timing for each measure. Closed symbols denote lean participants and open denote non-lean participants; circles denote month 1, squares month 2, and triangles month 3. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) with the strength of the scores are presented on each panel.

Individual differences in the clock time of the first, midpoint, and last caloric events during three different months (a–c) and relationship between timing of caloric events and months (d–i). Participants are ordered from earlier to later timing for each measure. Closed symbols denote lean participants and open denote non-lean participants; circles denote month 1, squares month 2, and triangles month 3. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) with the strength of the scores are presented on each panel. Solid and dashed-lines represent significant correlations between months in lean and non-lean participants, respectively.

Influence of body composition on stability of eating behaviors relative to clock timing

When comparing the lean and non-lean participants’ meal timing between months, there was a significant positive association for dinner timing in both lean (r = 0.84, p = 0.01) and non-lean (r = 0.83, p = 0.04) groups and for snack timing in the non-lean group (r = 0.94, p = 0.02) between months 1 and 2. There were also significant positive associations when comparing months 1 and 3 for breakfast (r = 0.85, p = 0.03), lunch (r = 0.86, p = 0.03), and dinner (r = 0.94, p < 0.01) in the non-lean group; there were no significant associations when comparing month 1 and 2. When examining consistency between months in the timing of first, midpoint, and last daily caloric events, we found significant positive associations for the timing of first, midpoint, and last daily caloric events in the non-lean group between months 1 and 2 and a significant positive association in the timing of first daily caloric event between months 1 and 3 for both groups (all p ≤ 0.05, Fig. 2d–i).

Stability of eating behaviors by circadian timing

To examine meal timing in relation to a physiological marker, the timing of caloric events was analyzed relative to DLMO. We first analyzed meals within 4 h of DLMO until sleep onset as any caloric events eaten during that time would likely result in a postprandial energetic response that would continue after DLMO33 and to be consistent with our prior work16. At the group level, there were no significant effects of month across the study for: the percentage of calories consumed within 4 h of DLMO until sleep onset; the circadian phase of peak caloric timing; or the timing of caloric midpoint relative to DLMO (Table 1). Nonetheless, when examining the relationship on an individual level, the ICC score for percentage of calories consumed within 4 h of DLMO until sleep onset had a moderate relationship strength, whereas the ICC scores for circadian phase of peak caloric timing and the timing of caloric midpoint relative to DLMO both had a fair relationship strength (Fig. 3a–c).

Individual differences in the circadian timing of caloric events during three different months (a–c) and relationship between circadian timing of caloric events and months (d–i). Participants are ordered from earlier to later timing for each measure. Closed symbols denote lean participants and open denote non-lean participants; circles denote month 1, squares month 2, and triangles month 3. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) with the strength of the scores are presented on each panel. Solid and dashed-lines represent significant correlations between months in lean and non-lean participants, respectively. DLMO, dim-light melatonin onset. A circadian phase of 0° denotes timing of DLMO.

Influence of body composition on stability of eating behaviors relative to circadian timing

There were no significant associations in lean and non-lean participants when examining consistency between months for the percentage of calories consumed within 4 h of DLMO until sleep onset (both p > 0.06). For the circadian phase of peak caloric timing and the timing of caloric midpoint relative to DLMO, however, we observed significant positive associations between months 1 and 2 in the non-lean group, but not the lean group (Fig. 3d–i).

Stability of caloric and macronutrient intake

On average, our study participants consumed 1627 kcal (127, 840–2346) daily across the three months during the study, with a significant effect of month (Table 1). However, there were no significant differences in daily calories consumed between particular months by planned comparisons (all Bonferroni-corrected p > 0.03). These calories were consumed in an average of 2.9 meals (0.3, 1.7–6.4) per day, with no significant month effect for meal number. In regards to macronutrients consumed, there were no significant main effects for percentage of daily calories from fat, carbohydrates, or protein consumed at the group level across months (Table 1).

Individuals were relatively consistent across months for caloric intake (Fig. 4). In particular, we found that the strength of the ICC relationships ranged from moderate (percent of daily calories from fat) to substantial (daily calories and percent of daily calories from carbohydrates) to almost perfect (percent of daily calories from protein) (Fig. 4). There was no intra-individual consistency between macronutrients (e.g., consistency in percent of fat intake was not always associated with consistency of carbohydrate intake). In terms of meal number, we found that individuals were moderately consistent across months, with a significant positive association between number of meals in months 1 and 2 (r = 0.90, p = 0.002) and months 1 and 3 (r = 0.89, p = 0.04) for lean participants, but not for non-lean participants (r = 0.75, p = 0.09 and r = 0.28, p = 0.59, respectively).

Individual differences in daily caloric intake (a), percent of daily calories from fat (b), carbohydrates (c), and proteins (d) during three different months. Participants are ordered from lower to higher amounts for each measure. Closed symbols denote lean participants and open denote non-lean participants; circles denote month 1, squares month 2, and triangles month 3. Intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) with the strength of the scores are presented on each panel.

Discussion

Determining the reproducibility, or stability, of behaviors significantly associated with optimal health from cross-sectional findings is fundamental to the scientific process. The current study reveals that although there were significant differences in several of our variables of interest at the month level, the individual stability of timing of eating in these participants living in real-world settings was fair-to-almost perfectly stable when measured across a week and compared across 3-months of observation relative to clock time. Moreover, day-to-day timing of eating was only slight-to-moderately consistent at the individual level, which may suggest two relevant time scales: a monthly timescale with more stability in eating timing than a daily timescale. Taken together, these data suggest that week-long cross-sectional studies regarding eating behaviors are likely reflecting habitual behaviors at the individual level, and that a single day’s food documentation may not represent habitual (i.e., longer time-scale) behaviors.

Unique to this study, we analyzed the consistency of meal timing across multiple months of observation, both as clock time and in relation to circadian time. Interestingly, the strength of individual stability tended to be strongest when clock timing of caloric events (i.e., first, midpoint, and last caloric event) were analyzed rather than participant identified meals. It was expected that the timing of caloric events would fare better than self-identified meals, as caloric events are unaffected by a skipped or misidentified meals. This point is highlighted by the fact that the participants’ average first caloric event tended to be later than a meal identified as breakfast, potentially signifying a skipping of breakfast. We suggest that future studies using timing of any caloric intake rather than timing of a meal as the appropriate metric.

Interestingly, clock timing of caloric events was more stable than caloric events in relation to circadian timing. One explanation for these findings could be external constraints (i.e., a social component, short amount of time, other obligations) of when a participant may choose to eat their primary meals (i.e., breakfast, lunch, and dinner)34. For example, because snacking is often done alone and meals are more commonly consumed with others35, the timing of when a social network is available to eat together on a daily basis could drive meal timing and decrease stability in eating relative to circadian time. We have recently shown that students attending the same college can have wide ranges of DLMO timing (> 10 h)17, and thus if meal timing is partially influenced by social constructs, two participants with large differences in DLMO choosing to eat together would decrease stability relative to circadian time but not clock time. The fact that the timing of dinner and the last daily caloric events were similar may support this point, as individuals may choose to eat with others as opposed to eating alone later at night. Despite this explanation, and other exogenous causes of variability, it is important to note that the stability of meal timing was always at least fair in strength. Future work is needed in identifying the consistency of meal timing relative to circadian timing outside of the college setting and also how social constructs may influence the timing of eating.

In addition to examining the stability of meal timing at an individual level, we also performed an exploratory analysis of the stability of meal timing when participants were separated into lean and non-lean body composition groups. Counter to our initial hypothesis, we found that non-lean individuals tended to have higher stability in timing of meals and caloric events between months (significant correlations in 11 out of 30 of our timing metrics) as compared to the lean group (4 out of 30 timing metrics). Because we found that our non-lean group had more stable DLMO timing across months, this could help account for the more regular timing of calories relative to circadian timing. This was unexpected as previous accounts have found less stable eating patterns associated with higher body fat compositions and poorer health20,21,22. One potential explanation for our differences in findings may be how stable meal intake is defined. Often, stability is described as the number of meals consumed within a day; this was not how we defined it here. A more variable number of meals consumed day-to-day, or frequency of meals, tends to be associated with poorer health21,36,37.

Our finding that day-to-day stability across months within an individual was somewhat poor, as compared to the average timing of caloric events, might reflect a general reliability issue for metrics of stability38. Mean values may have good reliability with few measurements, whereas variability measures (e.g., standard deviation) often need a high number of repeated observations to achieve reasonable reliability (i.e., as many as 5039). Thus, an increased observation sample may help to improve day-to-day stability metrics. Another potential problem with single day assessments of dietary behaviors may be altered behaviors associated with the recording of those behaviors; this change in behaviors is less likely with longer recording durations.

Although our protocol spanned over an entire semester, with three separate highly controlled inpatient overnight-visits, this study is not without limitations. First, our low sample size limited our ability to draw conclusions for some lean vs. non-lean metrics, for non-college or other college populations, and about the timing of meals and cardiometabolic health. Previously, we have shown that the circadian timing of caloric intake is associated with higher body fat composition16. In the current study, we were under-powered to perform any regression analysis in regard to meal timing and body composition metrics, and thus could not test to replicate our previous findings. Second, although we intentionally studied participants across the duration of a semester, inherent changes associated with a progressing semester (e.g., exams, seasonal changes, etc.) may have led to exogenous influences impacting our outcome measures. Moreover, by recording data across 7-consecutive days during each measurement interval, we may have increased day-to-day variability due to caloric events potentially being later on free-days as compared to school/work days. However, we would argue that these exogenous influences due to real-life demands actually strengthen our findings as they demonstrate how robust the stability of these behaviors are despite outside influence and allow for real-world generalizability of our findings. Future work randomizing or starting cohorts at serial times and including populations that are not college students are still needed to fully elucidate the repeatability of our metrics.

In summary, our findings document the stability of the timing of caloric consumption in relation to both clock hour and the physiological circadian timing. Our findings suggest that food intake timing of eating is fairly stable across multiple months within individuals, even though day-to-day variability of the timing of eating within a week in individuals has poor stability, suggesting that a single day’s food documentation may not represent habitual behaviors. Lastly, our surprising findings that non-lean individuals tended to have a higher stability of meal timing, and the relation between stability, body composition, and cardiometabolic health needs further examination.

Data availability

Data are archived on Brigham and Women’s Hospital servers and available upon request.

References

Hales, C.M., Carroll, M.D., Fryar, C.D. & Ogden, C.L. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2015–2016. NCHS Data Brief, 1–8 (2017).

National Academies of Sciences, E. & Medicine. Current status and response to the global obesity pandemic: proceedings of a workshop (National Academies Press, 2019).

Roberto, C. A. et al. Patchy progress on obesity prevention: emerging examples, entrenched barriers, and new thinking. Lancet 385, 2400–2409 (2015).

Mokdad, A. H. et al. The spread of the obesity epidemic in the United States, 1991–1998. JAMA 282, 1519–1522 (1999).

McTigue, K. M., Garrett, J. M. & Popkin, B. M. The natural history of the development of obesity in a cohort of young U.S. adults between 1981 and 1998. Ann. Intern. Med. 136, 857–864 (2002).

Sheehan, T. J., DuBrava, S., DeChello, L. M. & Fang, Z. Rates of weight change for black and white Americans over a twenty year period. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 27, 498–504 (2003).

Nelson, M. C., Story, M., Larson, N. I., Neumark-Sztainer, D. & Lytle, L. A. Emerging adulthood and college-aged youth: an overlooked age for weight-related behavior change. Obesity (Silver Spring) 16, 2205–2211 (2008).

Levitsky, D. A., Halbmaier, C. A. & Mrdjenovic, G. The freshman weight gain: a model for the study of the epidemic of obesity. Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 28, 1435–1442 (2004).

Serdula, M. K. et al. Do obese children become obese adults? A review of the literature. Prev. Med. 22, 167–177 (1993).

Garaulet, M. & Gomez-Abellan, P. Timing of food intake and obesity: a novel association. Physiol. Behav. 134, 44–50 (2014).

Mattson, M. P. et al. Meal frequency and timing in health and disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 16647–16653 (2014).

Bass, J. & Takahashi, J. S. Circadian integration of metabolism and energetics. Science (New York, N.Y.) 330, 1349–1354 (2010).

Laposky, A. D., Bass, J., Kohsaka, A. & Turek, F. W. Sleep and circadian rhythms: key components in the regulation of energy metabolism. FEBS Lett. 582, 142–151 (2008).

Scheer, F. A., Hilton, M. F., Mantzoros, C. S. & Shea, S. A. Adverse metabolic and cardiovascular consequences of circadian misalignment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 4453–4458 (2009).

Jakubowicz, D., Barnea, M., Wainstein, J. & Froy, O. High caloric intake at breakfast vs. dinner differentially influences weight loss of overweight and obese women. Obesity (Silver Spring) 21, 2504–2512 (2013).

McHill, A. W. et al. Later circadian timing of food intake is associated with increased body fat. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 106, 1213–1219 (2017).

McHill, A. W. et al. Caloric and macronutrient intake differ with circadian phase and between lean and overweight young adults. Nutrients 11, 587 (2019).

Gluck, M. E., Venti, C. A., Salbe, A. D. & Krakoff, J. Nighttime eating: commonly observed and related to weight gain in an inpatient food intake study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 88, 900–905 (2008).

Baron, K. G., Reid, K. J., Kern, A. S. & Zee, P. C. Role of sleep timing in caloric intake and BMI. Obesity (Silver Spring) 19, 1374–1381 (2011).

Pot, G. K., Almoosawi, S. & Stephen, A. M. Meal irregularity and cardiometabolic consequences: results from observational and intervention studies. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 75, 475–486 (2016).

Sierra-Johnson, J. et al. Eating meals irregularly: a novel environmental risk factor for the metabolic syndrome. Obesity (Silver Spring) 16, 1302–1307 (2008).

Guinter, M. A., Park, Y. M., Steck, S. E. & Sandler, D. P. Day-to-day regularity in breakfast consumption is associated with weight status in a prospective cohort of women. Int. J. Obes. (Lond.) 44, 186–194 (2020).

Gill, S. & Panda, S. A smartphone app reveals erratic diurnal eating patterns in humans that can be modulated for health benefits. Cell Metab. 22, 789–798 (2015).

Gupta, N. J., Kumar, V. & Panda, S. A camera-phone based study reveals erratic eating pattern and disrupted daily eating-fasting cycle among adults in India. PLoS ONE 12, e0172852 (2017).

Fischer, D. et al. Irregular sleep and event schedules are associated with poorer self-reported well-being in US college students. Sleep 43, zsz300 (2020).

Phillips, A. J. K. et al. Irregular sleep/wake patterns are associated with poorer academic performance and delayed circadian and sleep/wake timing. Sci. Rep. 7, 3216 (2017).

Feskanich, D., Sielaff, B. H., Chong, K. & Buzzard, I. M. Computerized collection and analysis of dietary intake information. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 30, 47–57 (1989).

Johnson, R. K., Driscoll, P. & Goran, M. I. Comparison of multiple-pass 24-hour recall estimates of energy intake with total energy expenditure determined by the doubly labeled water method in young children. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 96, 1140–1144 (1996).

Fischer, D., Vetter, C. & Roenneberg, T. A novel method to visualise and quantify circadian misalignment. Sci. Rep. 6, 38601 (2016).

Jeukendrup, A. & Gleeson, M. Sport nutrition: an introduction to energy production and performance (Human Kinetics, Champaign, 2010).

McGraw, K. O. & Wong, S. P. Forming inferences about some intraclass correlation coefficients. Psychol. Methods 1, 30 (1996).

Landis, J. R. & Koch, G. G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33, 159–174 (1977).

Reed, G. W. & Hill, J. O. Measuring the thermic effect of food. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 63, 164–169 (1996).

Dashti, H. S., Scheer, F., Saxena, R. & Garaulet, M. Timing of food intake: identifying contributing factors to design effective interventions. Adv. Nutr. 10, 606–620 (2019).

Wansink, B., Payne, C. R. & Shimizu, M. Is this a meal or snack? Situational cues that drive perceptions. Appetite 54, 214–216 (2010).

Farshchi, H. R., Taylor, M. A. & Macdonald, I. A. Beneficial metabolic effects of regular meal frequency on dietary thermogenesis, insulin sensitivity, and fasting lipid profiles in healthy obese women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 81, 16–24 (2005).

Kahleova, H., Lloren, J. I., Mashchak, A., Hill, M. & Fraser, G. E. Meal frequency and timing are associated with changes in body mass index in adventist health study 2. J. Nutr. 147, 1722–1728 (2017).

Estabrook, R., Grimm, K. J. & Bowles, R. P. A Monte Carlo simulation study of the reliability of intraindividual variability. Psychol. Aging 27, 560–576 (2012).

Wang, L. P. & Grimm, K. J. Investigating reliabilities of intraindividual variability indicators. Multivariate Behav. Res. 47, 771–802 (2012).

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants and Center for Clinical Investigation staff for their support in conducting these studies. We also thank the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Media Lab Affective Computing group.

Funding

NIH (Grants K01HL146992, F32DK107146, T32HL007901, K24HL105664, R01HL114088, R01GM105018, R01HL128538, P01AG009975, R21HD086392, R01 DK099512, R01 HL140574) and NSBRI (Grants HFP02802, HFP04201, HDP0006). This work has been supported in part by The Spanish Government of Investigation, Development and Innovation (SAF2017-84135-R) including FEDER co-funding; The Autonomous Community of the Region of Murcia through the Seneca Foundation (20795/PI/18) and NIDDK R01DK105072 granted to M. Garaulet.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Designed research, A.W.M., C.J.H., D.F., C.A.C., M.G., F.A.J.L.S. and E.B.K.; Conducted research, A.W.M., C.J.H., and E.B.K.; Analyzed data, A.W.M., D.F.; Writing—original draft, A.W.M.; Writing—review & editing, A.W.M., C.J.H, D.F., C.A.C., M.G., F.A.J.L.S. and E.B.K.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

M.G. and D.F. have no competing interests to disclose; A.W.M. reports speaker honorarium or travel reimbursement fees from the Utah Sleep Research Society and the California Precast Concrete Association; C.J.H. has received travel reimbursement from Integrated Safety Support and Deliberate Innovation; C.A.C. reports grants to BWH from FAA, NHLBI, NIA, NIOSH, NASA, and DOD; is/was a paid consultant to AARP (2018), American Academy of Dental Sleep Medicine (2017, 2018), Eisenhower Medical Center (2018), Emory University (2019), Ganésco, Inc. (2017), Inselspital Bern (2019), Institute of Digital Media and Child Development (2017, 2018, 2019), Klarman Family Foundation (2017, 2018, 2019), M. Davis and Co (2018), Physician's Seal (2019), Samsung (2016), Sleep Research Society Foundation (2019), State of Washington Board of Pilotage Commissioners (2018), Tencent Holdings Ltd (2019), Teva Pharma Australia (2019, 2020), UC San Diego (2018), University of Michigan (2017), University of Washington (2017, 2018), and Vanda Pharmaceuticals Inc (2017, 2018, 2019, 2020), in which Dr. Czeisler also holds an equity interest; received travel support from Annenberg Center for Health Sciences at Eisenhower (2018), Aspen Brain Institute (2018), Bloomage International Investment Group, Inc. (2018, 2019), UK Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (2019), Bouley Botanical (2017, 2018, 2019), Dr. Stanley Ho Medical Development Foundation (2019), European Biological Rhythms Society (2017, 2019), German National Academy of Sciences (Leopoldina) (2019), Illuminating Engineering Society (2018), National Safey Council (2017, 2018, 2019), National Sleep Foundation (2017, 2018, 2019), Society for Research on Biological Rhythms (2018), Sleep Research Society Foundation (2018), Stanford Medical School Alumni Association (2019), Tencent Holdings Ltd (2019), University of Zurich (2018), and Vanda Pharmaceuticals Inc (2017, 2018, 2019), Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München (2018), National Highway Transportation Safety Administration (2018), Office of Naval Research (2018), Salk Institute for Biological Studies/Fondation Ipsen (2018), The National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2017), The Wonderful Company (2017), Department of Defense (2017); receives research/education support through BWH from Cephalon, Mary Ann & Stanley Snider via Combined Jewish Philanthropies, Harmony Biosciences LLC (2019), Jazz Pharmaceuticals PLC Inc (2017, 2018, 2019, 2020), Johnson & Johnson (2019), NeuroCare, Inc. (2019), Philips Respironics Inc/Philips Homecare Solutions (2017, 2018, 2019, 2020), Regeneron Pharmaceuticals (2018, 2019, 2020), Regional Home Care (2019), Teva Pharmaceuticals Industries Ltd, Sanofi SA, Optum, ResMed, San Francisco Bar Pilots, Sanofi, Schneider, Simmons, Sysco, Philips, Vanda Pharmaceuticals; is/was an expert witness in legal cases, including those involving Advanced Power Technologies, Aegis Chemical Solutions LLC (2019), Amtrak (2019); Casper Sleep Inc (2019), C&J Energy Services (2019), Complete General Construction Co (2017), Dallas Police Association (2019), Enterprise Rent-A-Car (2019), Espinal Trucking/Eagle Transport Group LLC/Steel Warehouse Inc (2017, 2018, 2019), FedEx, Greyhound Lines Inc/Motor Coach Industries/FirstGroup America (2017, 2018, 2019), Pomerado Hospital/Palomar Health District (2017, 2018), PAR Electrical Contractors Inc (2019), Product & Logistics Services LLC/Schlumberger Technology Corp/Gelco Fleet Trust (2019), Puckett Emergency Medical Services LLC (2019), South Carolina Central Railroad Company LLC (2017, 2018), Union Pacific Railroad (2019), United Parcel Service/UPS Ground Freight Inc (2017, 2018), and Vanda Pharmaceuticals (2019, 2020); serves as the incumbent of an endowed professorship provided to Harvard University by Cephalon, Inc.; and receives royalties from McGraw Hill, and Philips Respironics (2017, 2018, 2019) for the Actiwatch-2 and Actiwatch Spectrum devices. Dr. Czeisler’s interests were reviewed and are managed by the Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Mass General Brigham in accordance with their conflict of interest policies. F.A.J.L.S. has received lecture fees from Bayer HealthCare, Sentara HealthCare, Philips, Vanda Pharmaceuticals, and Pfizer Pharmaceuticals. E.B.K. has received travel reimbursement from the Sleep Research Society, the National Sleep Foundation, the Santa Fe Institute, the World Conference of Chronobiology, and the Gordon Research Conference; she was paid by the Puerto Rico Trust for a grant review, and has consulted for the National Sleep Foundation.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

McHill, A.W., Hilditch, C.J., Fischer, D. et al. Stability of the timing of food intake at daily and monthly timescales in young adults. Sci Rep 10, 20849 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-77851-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-77851-z

This article is cited by

-

The association between diet quality and chrononutritional patterns in young adults

European Journal of Nutrition (2024)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.