Abstract

Malaysia is a country with an intermediate endemicity for hepatitis B. As the country moves toward hepatitis B and C elimination, population-based estimates are necessary to understand the burden of hepatitis B and C for evidence-based policy-making. Hence, this study aims to estimate the prevalence of hepatitis B and C in Malaysia. A total of 1458 participants were randomly selected from The Malaysian Cohort (TMC) aged 35 to 70 years between 2006 and 2012. All blood samples were tested for hepatitis B and C markers including hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), anti-hepatitis B core antibody (anti-HBc), antibodies against hepatitis C virus (anti-HCV). Those reactive for hepatitis C were further tested for HCV RNA genotyping. The sociodemographic characteristics and comorbidities were used to evaluate their associated risk factors. Descriptive analysis and multivariable analysis were done using Stata 14. From the samples tested, 4% were positive for HBsAg (95% CI 2.7–4.7), 20% were positive for anti-HBc (95% CI 17.6–21.9) and 0.3% were positive for anti-HCV (95% CI 0.1–0.7). Two of the five participants who were reactive for anti-HCV had the HCV genotype 1a and 3a. The seroprevalence of HBV and HCV infection in Malaysia is low and intermediate, respectively. This population-based study could facilitate the planning and evaluation of the hepatitis B and C control program in Malaysia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a partially double stranded DNA virus that belongs to the hepatitis DNA viruses (hepadnaviruses), while hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a plus-stranded RNA virus of the Flaviviridae family. Infection with HBV and/or HCV were associated with the development of liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma1,2. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that by 2017, approximately 248 million people will be living with chronic HBV infection and 110 million people with HCV infection; of these, 80 million people will have an active viral infection3,4. Most HBV and HCV infections are asymptomatic, and about 90% of patients infected with HCV are unaware that they have the virus that makes them a healthy carrier5. Nonetheless, both HBV and HCV infections are generally preventable, treatable and potentially curable if they are diagnosed at an early stage1,2.

The Ministry of Health (MoH), Malaysia has reported that about 5% of Malaysian population is infected with HBV6. Despite the incidence of HBV in Malaysia being constant between 11 and 15% for the past 5 years (since 2015) and the introduction of HBV vaccination in 1989, the incidence of hepatitis B (HB) is projected to increase between 2010 and 20407. This will add an additional burden on health services due to the chronic sequelae of HB due to the higher rates of hospitalization and treatment for liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, which is currently among the eight most common types of cancer in Malaysia8. A population based seroprevalence study could provide insights on the current situation of HB in Malaysia including the impact of HB vaccination policy and existing screening strategies to further mitigate HB transmission in the community.

About 2 to 2.5% of the Malaysian population is infected with HCV6. The HCV infection in Malaysia is projected to rise steeply over the coming decades. A total of 64,000 hepatitis C-related death was projected to happen in 2039 with a total of 2002 and 540 individuals will developed decompensated cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma, respectively9. Thus, it is important to determine the true prevalence of HBV and HCV infection in the Malaysian population in order to determine the burden of infection and to estimate the size of the chronically infected community and those in need of treatment. Such data can be used in health planning or policy decision making in order to reduce the transmission of HBV and HCV and the mortality rates. The data may also facilitate the health authorities to review priorities, improve and extend early screening and strategies to reduce the burden of chronic HBV and HCV infection. To date, no population-based studies have been conducted to ascertain the prevalence of HBV and HCV infections among the adult population of Malaysia.

Therefore, this study aims to determine the prevalence of HBV and HCV (seroprevalence) infection in Malaysian adult population by determining the presence of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), antibody to hepatitis B core antigen (anti-HBc) and antibody to hepatitis C virus (anti-HCV) in the serum.

Results

The baseline characteristics for the 1458 The Malaysian Cohort (TMC) participants are presented in Supplementary Table S1. The cohort comprises randomly chosen individuals who were recruited between 2007 and 2012 and mostly in 2011 (24%). Most of the participants were between 45 and 54 years old, Malays (40%), married (89%), had attained secondary education level (51%), working in the non-governmental sectors (43%), from the state of Selangor (24%) and urban area (71%).

Majority of the participants had no history of hepatitis A and B immunisation (82%), no history of chronic hepatitis (99.8%) and no history of blood transfusion (92%). The proportion was almost similar for individuals with or without history of surgery. All the participants had no family history of chronic hepatitis.

Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)

The seroprevalence of HBsAg was 4% as depicted in Table 1. There were differences between patients’ characteristics and status of HBsAg test. Those were positive HBsAg were aged between 55 and 64 years old (5%), male (5%), from the rural area (5%), among the Bumiputera ethnic group in Sabah (11%), married (4%), with no formal education (8%), unemployed (4%) and with no history of blood transfusion (3%). It is interesting to know that although no history of hepatitis immunization was statistically associated with HBsAg positivity, for immunized persons we found the highest proportion of positives in those vaccinated against hepatitis A virus. In addition, those who had history of chronic hepatitis was statistically associated with HBsAg positivity. However, only gender, ethnicity and history of chronic hepatitis disease showed significant differences with the status of HBsAg test. There were four out of 1458 samples which were equivocal. All equivocal samples were Malays, had no history of chronic hepatitis and blood transfusion, were married and working with the non-government sector.

Gender, ethnicity and locality were significantly associated with HBsAg seropositivity in the crude analysis (Table 2). The final multivariable models for HBsAg seropositivity included gender, ethnicity, locality, and immunisation history, history of surgery and history of blood transfusion. All these factors contributed to 8% risk of HBsAg seropositivity. History of chronic hepatitis was removed from the model due to high collinearity. Immunisation history, history of surgery and history of blood transfusion were included in the final models due to the clinical importance of the information. None of the other risk factors showed association with the status of HBsAg (p < 0.20) or were retained in the multivariable model.

In the final model, after adjusting for other confounding factors, males had two times significantly higher odds of HBsAg seropositivity compared to females (OR 2.0, 95% CI 1.1–3.8, p = 0.02). Compared to the Malays, the Chinese had the significantly highest odds in HBsAg seropositivity (OR 4.9, 95% CI 2.2–11.2, p < 0.001), followed by Bumiputera Sabah (OR 4.6, 95% CI 1.9–11.2, p = 0.001) and Bumiputera Sarawak (OR 3.9, 95% CI 1.2–12.8, p = 0.027). Those who lived in rural areas had a twofold significantly higher risk of HBsAg seropositivity than those who lived in urban areas (OR 2.1, 95% CI 1.0–4.3, p = 0.044). Participants who had a history of blood transfusion had higher risk than those who did not have history of blood transfusion, although the result was significant (OR 2.4, 95% CI 0.9–5.9, p = 0.054). Even though the results were not significant, the individuals with history of surgery and history of hepatitis A immunisation showed 26% and 25% higher HBsAg seropositivity respectively.

Antibody to hepatitis B core antigen (anti-HBc)

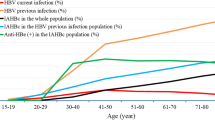

The prevalence of hepatitis B core antigen (anti-HBc) positive was 20% as shown in Table 3. Majority of those with hepatitis B core antigen seropositivity (anti-HBc) were recruited in 2007 (25%), aged 65 to 70 (35%), and working in non-government sectors (20%). Similar to HBsAg, those were male (23%) and lived in rural areas (23%), were Bumiputera Sabah (44%), had no formal education (40%), with history of chronic hepatitis, were more likely to be positive in hepatitis B core antigen serology. However, only age, gender, ethnicity, education level, state, locality and history of chronic hepatitis were significantly associated with the status of anti-HBC serology. There were 53 (4%) participants who were positive for both HBsAg and anti-HBc.

The final multivariable model consisted of age, gender, ethnicity, state, history of immunisation, history of surgery and history of blood transfusion, and together these factors contributed to 10% of anti-HBc seropositivity (Table 4). The risk of anti-HBc seropositivity significantly increased with age and was 53% higher among males than females. The risk was significantly higher among Bumiputera Sabah, followed by Chinese and Bumiputera Sarawak. However, anti-HBc seropositivity was substantially higher by almost threefold in those from the state of Terengganu. Those who had history of hepatitis B immunisation only and those who had both A and B immunisation were significantly protected against HBV compared to those who had no history of immunisation.

Antibody to hepatitis C virus (anti-HCV)

The hepatitis C seropositivity (anti-HCV) was 0.3% (Table 5). Majority of those who were anti-HCV positive were recruited in 2011, aged between 55 and 64 years old, males, Malays, single, had primary education, self-employed, had no history of immunisation, no history of chronic hepatitis, had history of surgery and had history of blood transfusion. However, none of the risk factors were significantly associated with the serology status of anti-HCV. Interestingly, two of them (0.2%) were positive for both anti-HCV and anti-HBc.

The final multivariable model included marital status and history of blood transfusion which contributed to 13% of anti-HCV seropositivity (Table 6). Those who were married had lower risk of getting anti-HCV seropositivity compared to those who were single. While those who had history of blood transfusion had two times higher risk of getting anti-HCV seropositivity compared to those who had no history.

Discussion

This study showed that the prevalence of HBsAg and anti-HBc among the Malaysian adult population were 4% and 20%, respectively. The prevalence of HBsAg positive was higher than the previous studies conducted among the blood donors in Kelantan (1%) and thalassaemic patients in the National University of Malaysia hospital (HUKM) (2%), but lower than previous studies conducted among Negrito tribe in Kelantan (9%) and Malaysian volunteers in 1997 (5%)10,11,12,13. In contrast, the prevalence of anti-HBc in Malaysia from this study was lower than the prevalence among the adult population in Turkey (23%), Romania (27%), Northeast China (36%) and Korea (39%)14,15,16,17. However, the prevalence of anti-HBc positive in Malaysia is higher than in Croatia (7%), France (7%), Germany (9%), and Iran (16%)18,19,20,21.

The low prevalence of HBsAg among our participants may suggest that less people were acutely infected at the moment of blood collection. Result from this study indicated that HB endemicity level in Malaysia is intermediate13. Our study showed that being male was significantly associated with HBsAg seropositivity and similar finding were reported in Brazil and China22,23. Our study also found that those who lived in the rural areas had a higher risk of being HBsAg positive. There are several factors that may be associated with higher prevalence of HBsAg positive in rural areas including limited access to health care services and low vaccination coverage12,24.

The high prevalence of anti-HBc could be from acquired immunity from natural infection because the HBV vaccination program in Malaysia was introduced in 1989 and all the participants were born before 198925. This might explain the reason we found that the prevalence of anti-HBc was higher among older people and those who were not vaccinated in this study. This would imply that most of them were asymptomatic and without any treatment, might lead to the chronic sequalae of HB. These individuals, including their family members who are probably undiagnosed and asymptomatic, pose a potential risk for the mode of transmission for hepatitis. The similar finding were reported in Brazil, Germany, and Thailand where prevalence of anti-HBc were higher in those people who were born before the HB immunisation program was started22,26,27.

In this study, HBsAg and Anti-HBc positivity was found to be significantly associated with males. Several factors that may be attributed to high prevalence of HbsAg and Anti-HBc in men including high-risk sexual behavior and the usage of intravenous drug27,28. Our study also revealed that HB infection was prevalent in certain ethnic groups such as the Chinese, Bumiputera Sarawak and Bumiputera Sabah. Previous studies also reported that HBsAg positivity was more prevalent among the Chinese than other ethnic group in Malaysia6,13. Although the reasons behind the high rate of HB in certain ethnic groups are still unknown, previous study suggested that high-risk behaviour and cultural activity, such as unhygienic tattooing, body piercing, high-risk sexual activities, and alcohol consumption may have been contributed to high prevalence of HBsAg and Anti-HBc22,29. Thus, further study on the association of lifestyles, behaviour or occupational risk exposures and HBV infection in different populations and ethnicities were needed in order to explain the different levels of HB infection between different populations.

This study also found the prevalence of HCV was only 0.34%, which is a huge discrepancy as compared to the estimated prevalence based on modelling and routine screening in Malaysia6,9,30. This level was lower than in the previous studies conducted among blood donors in Malaysia in 1993 and 2012 and among adult population in Iran (0.5%), Oslo (0.7%), France (0.8%), Croatia (0.9%), Morocco (2%), Czech Republic (2%), and Romania (3%)18,19,21,31,32,33,34,35,36. HCV genotype 1a and 3a were found in the HCV-positive samples, and those two genotypes are the common HCV circulating genotypes in Malaysia37,38. Interestingly, in this study, there was no difference between most of the basic sociodemographic factors and HCV infection except for marital status. We found that being married was significantly associated with HCV infection. Similar finding was found in Pakistan whereby being married was significantly associated with higher odds of acquiring HCV infection and sexual transmission between spouses may increase the horizontal transmission between healthy individual and HCV-infected individual39.

This study has several limitations including the samples selection was based on simple random sampling and limited questionnaires to investigate further risk factors of hepatitis. Thus, it is recommended to conduct a serosurvey using proper randomization with the appropriate sampling design to obtain the true estimates of HBV and HCV in the population-based setting and incorporate questions that will examine a wider set of risk factors in order to obtain a better understanding of hepatitis infection while controlling for bias22,40,41. This is important to further understand the socio-economic impact of hepatitis infection thus enabling better management and specific intervention on the susceptible and vulnerable population.

As a conclusion, we found that the prevalence of HBsAg, anti-HBc and anti-HCV positivity among Malaysian adult population were 4%, 20%, and 0.3%, respectively. The prevalence of anti-HBc was high among older adults with low immunisation coverage and with no reported history of chronic HB. This indicate the importance of hepatitis screening and testing to prevent the transmission in the family and community. Awareness on hepatitis could also help to avoid the chronic sequelae if the infected person could seek early treatment. It is vital to identify social and behaviour risk factors of these susceptible populations who have not been vaccinated in order to understand how they acquire the infection.

Methods

Study population

The Malaysian Cohort (TMC) project is a prospective population-based study that was initiated in 200642. The project has recruited 106,527 Malaysians aged 35 to 70 years, from various ethnic groups, geographical locations, and lifestyles42. The cohort sampling was performed using a mixed approach of voluntary participants (through advertisement and publicity campaigns) and cluster sampling. Written informed consent was taken for: (i) the study interview; (ii) the biophysical examination, (iii) blood taking, baseline blood tests and storage of bio-specimens; and (iv) future research and recontact. The inclusion criteria included being a Malaysian citizen, in possession of a valid identification card, not suffering from any acute illness at the time of study and giving informed consent to the study. Detailed information about each participant was collected along with blood and urine samples prior of eight hours fasting.

The sample size for this seroprevalence study was calculated using a single proportion formula for estimation of prevalence incorporated with Neyman allocation for stratified sampling based on estimation of 2.5% prevalence of hepatitis C in Malaysia9. Hence, a total of 1458 serum samples were randomly identified from the initial population of 106,527 (Supplementary Table S1). Sociodemographic data including age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, education levels, and history of illness were retrieved from TMC database. All samples were anonymized prior to analysis.

Serological testing for hepatitis B and C markers

Five millilitres of venous blood were collected from each participant into a dry tube and centrifuged at 3000 rpm, for 10 min at 4 °C to separate the serum. The serum samples were aliquoted into cryotubes containing 500 µl each and stored at – 80 °C prior to use. Presence of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), antibody to hepatitis B core antigen (anti-HBc), and antibody to hepatitis C virus (anti-HCV) in the serum samples were screened by a chemiluminescence immunoassay (Roche Diagnostic, Germany; Abbott immunoassay, USA; Roche Diagnostic, Germany) on the Cobas analyser43,44,45. The results were interpreted in accordance with the manufacturers’ instructions. All equivocal results were retested using a sample from another cryotube belonging to the same individual. Samples reactive in the HCV screening assay were further tested to determine HCV RNA viral load and genotyping by Cepheid Xpert HCV Viral Load assay and sequencing, respectively46,47. Detection of HBsAg was considered indicative of chronic HBV infection and detection of anti-HCV was considered a marker of HCV infection23.

Questionnaire-derived variables

Baseline information related to demographic and medical histories were collected using questionnaires and interviews42. Family history of hepatitis was determined by asking the participants if their biological parents or siblings were ever diagnosed with hepatitis. Participants were also asked about history of immunisation, chronic hepatitis, blood transfusion and surgery. Locality was defined as rural or urban for each participant.

Missing data handling

Multiple imputation was performed by chained equations (MICE) with 25 cycles, based on a missing at random (MAR) assumption48. In each cycle, missing values for each variable were imputed based on a predictive distribution derived from regression on all other variables in the imputation model (education level, marital status, occupation, history of blood transfusion, chronic hepatitis and surgery, family history of hepatitis). Parameter estimates from the imputed datasets were combined using Rubin’s rules49.

Ethics statement

Ethics approval was obtained from the institutional review and ethics board of Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia (Project Code: FF-205-2007) in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants gave their written consent before being recruited in this study.

Statistical analysis

The overall prevalence of HBsAg, anti-HBc, and anti-HCV was expressed as the percentage of seropositive samples. The characteristics of the participants were compared with the serostatus of HBsAg, anti-HBc, and anti-HCV using chi-squared test. For statistical analysis, equivocal results were analysed together with negative results50,51. Multivariable logistic regression model was used to investigate associations of putative risk factors with seropositivity of HBsAg, anti-HBc, and anti-HCV adjusting for other confounding factors. For each analysis a variable selection process was used as previously described52. This involved an initially fitted a multivariable model including all selected risk factors, and then individually removing the least significant risk factor (p > 0.20), provided the likelihood ratio p-value for the nested models exceeded 0.20 and the estimated coefficients (on the logit scale) of all remaining variables did not differ by more than about 10%. Parameter estimates were expressed as odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI). A threshold of 0.05 was used for declaring significance. The risk explained by the classical risk factors was estimated using McFadden’s pseudo R2. All analyses were performed using STATA 14 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA) and GraphPad Prism 7 (GraphPad Software Inc., USA).

References

WHO. Hepatitis B Fact Sheets (World Health Organization, Geneva, 2019).

WHO. Hepatitis C Fact Sheets (World Health Organization, Geneva, 2019).

WHO. Guidelines on Hepatitis B and C Testing (World Health Organization, Geneva, 2018).

WHO. Prevention & Control of Viral Hepatitis Infection: Framework for Global Action (World Health Organization, Geneva, 2012).

Heymann, D. L. Control of Communicable Diseases Manual (American Public Health Association, Washington, DC, 2000).

Raihan, R. Hepatitis in Malaysia: past, present, and future. Euro. J. Hepato-Gastroenterol. 6, 52–55 (2016).

Rajamoorthy, Y., Taib, N. M., Rahim, K. A. & Munusamy, S. Trends and estimation of hepatitis B infection cases in Malaysia, 2003–2030. Malays. J. Public Health Med. 16, 113–120 (2016).

Raihan, R., Azzeri, A., Shabaruddin, F. H. & Mohamed, R. Hepatocellular carcinoma in Malaysia and its changing trend. Euroasian J. Hepato-gastroenterol. 8, 54–56 (2018).

McDonald, S. A. et al. Projections of the current and future disease burden of hepatitis C virus infection in Malaysia. PLoS ONE 10, e0128091 (2015).

Yousuf, R. et al. Trends in hepatitis B virus infection among blood donors in Kelantan, Malaysia: a retrospective study. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 38, 1070–1074 (2007).

Jamal, R. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B, hepatitis C, CMV and HIV in multiply transfused thalassemia patients: results from a thalassemia day care center in Malaysia. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Public Health 29, 792–800 (1998).

Sahlan, N. et al. hepatitis B virus infection: epidemiology and seroprevalence rate amongst Negrito tribe in Malaysia. Med. J. Malays. 74, 320–325 (2019).

Merican, I. et al. Chronic hepatitis B virus infection in Asian countries. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. (Australia) 15, 1356–1361 (2000).

Yildirim, B. et al. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B and C viruses in the province of Tokat in the Black Sea region of Turkey: a population-based study. Turk. J. Gastroenterol. Off. J. Turk. Soc. Gastroenterol. 20, 27–30 (2009).

Gheorghe, L., Csiki, I. E., Iacob, S. & Gheorghe, C. The prevalence and risk factors of hepatitis B virus infection in an adult population in Romania: a nationwide survey. Eur. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 25, 56–64 (2013).

Zhang, H. et al. Seroprevalence and risk factors for hepatitis B infection in an adult population in Northeast China. Int. J. Med. Sci. 8, 321 (2011).

Song, E. Y., Yun, Y. M., Park, M. H. & Seo, D. H. Prevalence of occult hepatitis B virus infection in a general adult population in Korea. Intervirology 52, 57–62 (2009).

Vilibić-Čavlek, T. et al. Prevalence of viral hepatitis in Croatian adult population undergoing routine check-up, 2010–2011. Cent. Eur. J. Public Health 22, 29–33 (2014).

Meffre, C. et al. Prevalence of hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus infections in france in 2004: social factors are important predictors after adjusting for known risk factors. J. Med. Virol. 82, 546–555 (2010).

Jilg, W. et al. Prevalence of markers of hepatitis B in the adult German population. J. Med. Virol. 63, 96–102 (2001).

Merat, S. et al. Seroprevalence of hepatitis C virus: the first population-based study from Iran. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 14(Suppl 3), e113–e116 (2010).

Pereira, L. M. M. B. et al. Population-based multicentric survey of hepatitis B infection and risk factor differences among three regions in Brazil. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 81, 240–247 (2009).

Wang, S. et al. Epidemiological study of hepatitis B and hepatitis C infections in Northeastern China and the beneficial effect of the vaccination strategy for hepatitis B: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 18, 1088 (2018).

Yang, S. et al. Prevalence and influencing factors of hepatitis B among a rural residential population in Zhejiang Province, China: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 7, e014947–e014947 (2017).

Ministry of Health Malaysia, D. C. D. Evaluation of hepatitis B control program in Malaysia. (unpublished).

Leroi, C. et al. Prevalence of chronic hepatitis B virus infection in Thailand: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 51, 36–43 (2016).

Poethko-Müller, C. et al. Die Seroepidemiologie der hepatitis A, B und C in Deutschland: Ergebnisse der studie zur gesundheit erwachsener in Deutschland (DEGS1). Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundh. Gesundh. 56, 707–715 (2013).

Wang, H. et al. hepatitis B infection in the general population of China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect. Dis. 19, 1–10 (2019).

Rajamoorthy, Y. et al. Risk behaviours related to hepatitis B virus infection among adults in Malaysia: a cross-sectional household survey. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cegh.2019.04.011 (2019).

Petruzziello, A., Marigliano, S., Loquercio, G., Cozzolino, A. & Cacciapuoti, C. Global epidemiology of hepatitis C virus infection: an up-date of the distribution and circulation of hepatitis C virus genotypes. World J. Gastroenterol. 22, 7824–7840 (2016).

Duraisamy, G., Zuridah, F. H., Ariffin, B. M. Y., Zuridah, H. & Ariffin, M. Y. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus antibodies in blood donors in Malaysia. Med. J. Malays. 48, 313 (1993).

Tamim, H. et al. Seroprevalence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection among blood donors: a hospital-based study. Transfus. Apher. Sci. 24, 29–35 (2001).

Dalgard, O. et al. hepatitis C in the general adult population of Oslo: prevalence and clinical spectrum. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 38, 864–870 (2003).

Baha, W. et al. Prevalence and risk factors of hepatitis B and C virus infections among the general population and blood donors in Morocco. BMC Public Health 13, 50 (2013).

Chlibek, R. et al. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus in adult population in the Czech Republic—time for birth cohort screening. PLoS ONE 12, e0175525 (2017).

Gheorghe, L. et al. The prevalence and risk factors of hepatitis C virus infection in adult population in Romania: a nationwide survey 2006–2008. J. Gastrointest. Liver Dis. 19, 373–379 (2010).

Mohamed, N. A., Zainol-Rashid, Z., Wong, K. K., Abdullah, S. A. & Rahman, M. M. Hepatitis C genotype and associated risks factors of patients at University Kebangsaan Malaysia Medical Centre. Pak. J. Med. Sci. 29, 1142–1146 (2013).

Ho, S.-H., Ng, K.-P., Kaur, H. & Goh, K.-L. Genotype 3 is the predominant hepatitis C genotype in a multi-ethnic Asian population in Malaysia. Hepatobiliary Pancreat. Dis. Int. 14, 281–286 (2015).

Qureshi, H., Bile, K. M., Jooma, R., Alam, S. E. & Afrid, H. U. R. Prevalence of hepatitis B and C viral infections in Pakistan: findings of a national survey appealing for effective prevention and control measures. East. Mediterr. Health J. 16, 15–23 (2010).

de Ximenes, R. A. A. et al. Methodology of a nationwide cross-sectional survey of prevalence and epidemiological patterns of hepatitis A, B and C infection in Brazil. Cad. Saude Publica 26, 1693–1704 (2010).

WHO. Immunization Vaccines and Biologicals (WHO, Geneva, 2011).

Jamal, R. et al. Cohort profile: the Malaysian cohort (TMC) project: a prospective study of non-communicable diseases in a multi-ethnic population. Int. J. Epidemiol. 44, 423–431 (2015).

Jia, J.-D. et al. Multicentre evaluation of the Elecsys® hepatitis B surface antigen II assay for detection of HBsAg in comparison with other commercially available assays. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 198, 263 (2009).

Seiskari, T., Lehtisaari, H., Haapala, A.-M. & Aittoniemi, J. From Abbott ARCHITECT® Anti-HBc to Anti-HBc II—Improved performance in detecting antibodies to hepatitis B core antigen. J. Clin. Virol. 47, 100–101 (2010).

Li, D. et al. Comparison of Elecsys anti-HCV II assay with other HCV screening assays. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 30, 451–456 (2016).

Grebely, J. et al. Time to detection of hepatitis C virus infection with the Xpert HCV viral load fingerstick point-of-care assay: facilitating a more rapid time to diagnosis. J. Infect. Dis. 221, 2043–2049 (2020).

Iwamoto, M. et al. Field evaluation of GeneXpert® (Cepheid) HCV performance for RNA quantification in a genotype 1 and 6 predominant patient population in Cambodia. J. Viral Hepat. 26, 38–47 (2019).

Royston, P. & White, I. R. Multiple imputation by chained equations (MICE): implementation in Stata. J. Stat. Softw. 45, 1–20 (2011).

Rubin, D. B. Multiple imputation after 18+ years. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 91, 473–489 (1996).

Abebe, A. et al. Seroepidemiology of hepatitis B virus in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: transmission patterns and vaccine control. Epidemiol. Infect. 131, 757–770 (2003).

Molton, J. et al. Seroprevalence of common vaccine-preventable viral infections in HIV-positive adults. J. Infect. 61, 73–80 (2010).

Greenland, S., Daniel, R. & Pearce, N. Outcome modelling strategies in epidemiology: traditional methods and basic alternatives. Int. J. Epidemiol. 45, 565–575 (2016).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Director General of Health Malaysia for his permission to publish this article.

Funding

This work was supported by Ministry of Health Malaysia (NMRR-18-836-40758) and Ministry of Education (PDE48).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.A.M., R.M.A.G., M.R.A.H., T.A. and R.J. conceived the study. M.H.A.M., E.N.M., H.M.H., R.M.Z., N.A., N.A.M.A., N.A.J., N.I., N.A.M.Y., R.O., A.S.K.A., M.S.A. and M.A.K. carried out the assay, performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. N.A.M., R.M.A.G., N.A., N.A.M.A., T.A. and R.J. participated in the experimental design and the analysis and interpretation of data. N.A.M., R.M.A.G., T.A. and R.J. critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Muhamad, N.A., Ab.Ghani, R.M., Abdul Mutalip, M.H. et al. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infection among Malaysian population. Sci Rep 10, 21009 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-77813-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-77813-5

This article is cited by

-

Identification of associated risk factors for serological distribution of hepatitis B virus via machine learning models

BMC Infectious Diseases (2024)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.