Abstract

The industrial production of Tenebrio molitor L. requires optimized rearing and processing conditions to generate insect biomass with high nutritional value in large quantities. One of the problems arising from processing is a tremendous loss in mineral accessibility, affecting, amongst others, the essential trace element Zn. As a feasible strategy this study investigates Zn-enrichment of mealworms during rearing to meet the nutritional requirements for humans and animals. Following feeding ZnSO4-spiked wheat bran substrates late instar mealworm larvae were evaluated for essential micronutrients and human/animal toxic elements. In addition, growth rate and viability were assessed to select optimal conditions for future mass-rearing. Zn-feeding dose-dependently raised the total Zn content, yet the Znlarvae/Znwheat bran ratio decreased inversely related to its concentration, indicating an active Zn homeostasis within the mealworms. The Cu status remained stable, suggesting that, in contrast to mammals, the intestinal Cu absorption in mealworm larvae is not affected by Zn. Zn biofortification led to a moderate Fe and Mn reduction in mealworms, a problem that certainly can be overcome by Fe/Mn co-supplementation during rearing. Most importantly, Zn feeding massively reduced the levels of the human/animal toxicant Cd within the mealworm larvae, a technological novelty of outstanding importance to be implemented in the future production process to ensure the consumer safety of this edible insect species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

World population is projected to reach ten billion people by the middle of the century. The United Nations therefore assume that between 2050 and 2070 food production needs to be twice as high as today in order to meet the expected increase in consumption1. Consequently, alternative food sources are becoming increasingly important. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, insects as an alternative environmentally friendly food and feed source are amongst the nutrients of choice for ensuring food security for the growing world population2. Just recently Europe has opened the utilization of insects for food (EU regulation 2015/22833) and feed (EU 2017/8934). There is an urgent need to define globally harmonized quality standards for animal farming, processing and marketing in view of food safety, nutritional quality, and consumer demands5,6. In 2015, the EFSA published a scientific opinion on a risk profile related to the production and consumption of insects as food and feed7,8. Amongst the insects evaluated, the yellow mealworm (Tenebrio molitor L., Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae) has received extensive attention because of its high macronutrient value (on a dry weight basis \(\sim\) 55% protein, 30% lipids, 7% carbohydrate)9 and its wide range of potential applications10,11. This makes these mealworms ideal candidates for cultivation and processing on an industrial scale12. With regard to economics and environmental issues, efforts have been made to improve mass production of the yellow mealworm by utilizing alternative raw materials with high nutritional value and low cost. In particular, wheat bran, a by‐product of industrial wheat flour milling amounting to about 150 million tons per year13, represents a highly economic, low-cost source of valuable nutrients for animals, including insects10,14,15. Recent studies showed the benefits of admixing agri-food industry by-products into wheat flour/bran for mealworm larvae rearing in terms of improved larval growth, diminished microbial load and improved antioxidant status16,17. Moreover, co-feeding of lipid- and protein-based supplements had a positive effect on macronutrient composition of mealworm larvae, upgrading them for food and feed applications18.

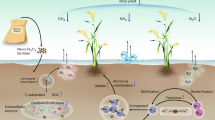

Little is known about the specific metabolic and nutritional response of yellow mealworms to alterations in dietary micronutrient supply. T. molitor larvae in principle are rich in vitamins and minerals9. The in vitro solubility and availability of essential minerals, particularly Zn, from fresh mealworms, however, is rather poor19. Mealworm drying even aggravates this problem20. A promising strategy for improving the mineral quality of T. molitor could be the use of Zn-enriched feed during breeding20. In this regard, the mealworm Zn tolerance needs to be determined, in order to minimize feed-aversion induced growth delays and mortality during rearing21. Moreover, excess Zn and minerals ingested with the feed may compete for intestinal transporters and intracellular chaperones in order to be efficiently delivered across the gut epithelium into the hemolymph. For mammals, intestinal competition between Zn and several other essential micronutrients (Cu, Fe, Ca) or toxic heavy metals (Pb, Cd) has been described22,23. Hence, the aim of this study was to investigate the potential dimensions of Zn enrichment in T. molitor during late instar larval development, when providing a ZnSO4-spiked wheat brain diet. Furthermore, it was to be investigated to what extent this fortification impacts the larval composition in essential and toxic elements, respectively. These results will be of utmost importance when aiming to improve T. molitor processing technologies, a basic prerequisite for utilizing mealworms as novel food or animal feed in the future.

Results

Larval growth parameters

Diet composition is one of the main variables determining the efficiency of feed conversion into biomass for a given insect species in industrial mass rearing. T. molitor larvae fed over the whole period with Znbasal wheat bran (Fig. 1) did effectively increase their starting L3–4 weight by a factor of 40, with very low mortality rate (Table 1). Overall 15.0 ± 0.5 g (around 75%) of the total offered Znbasal wheat bran material was consumed (FC) with a total assimilation (FA) of 6.7 ± 0.3 g. The increase in larval body weight is reflected in a favorable feed conversion ratio (FCR 5.1 ± 0.1) and feed conversion efficiency (ECI 19.5 ± 0.3%) (Table 1). Mealworms grown in any of the Zn-enriched wheat bran materials also remained highly viable until late instar, but were significantly lower in fresh weight at stage L9–10 (52.3 ± 1.6 mg Znbasal vs. 42.4 ± 1.8 mg Zn40; ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test Znbasal vs Zn40 p < 0.01), corresponding to a loss in biomass of around 20% (Table 1). Total feed consumption over the eight weeks feeding period was almost the same for the different groups, suggesting that the animals had no aversions against the spiked wheat bran, even though the added ZnSO4 was in the range of gustatory impact (0.35% w/w in the Zn40 wheat bran21). Likewise, total feces production was comparable, indicating that the overall amount of feed available for assimilation and growth (FA) was similar between the different feeding groups. Nevertheless, the slightly diminished feed conversion efficiency (ECI and ECD) of the Zn-enriched wheat bran (Table 1) suggests certain post-absorptive nutrient imbalances of the larvae, when starting from Zn-enriched bran, which seems to be restrictive for mealworm growth and development.

Zn-enrichment in T. molitor larvae

Based on FC, total Zn intake for the Znbasal group during the feeding period was estimated to be 1.4 ± 0.1 mg (\(\sim\) 24.3 ± 0.9 µg Zn/ animal; Fig. 2B). Total Zn content in the final biomass of the Znbasal L9–10 larvae was 116.4 ± 4.3 mg kg−1 dry weight (Fig. 2A). Yet the larvae are higher in total Zn than the feeding material, indicating an accumulation of the essential mineral within the animals (Fig. 2C). Wheat bran contains significant amounts of phytate, an anti-nutrient inhibiting intestinal Zn absorption in both invertebrates and vertebrates24,25. Assuming a typical phytate content of \(\sim\) 6000 mg/100 g wheat bran26, the estimated phytate/Zn molar ratio for the Znbasal feed corresponds to 66, which might be disadvantageous for larval midgut Zn accessibility. In the Zn-spiked feed this ratio is shifted in favor of Zn, decreasing the molar phytate/Zn-ratio to 3.8 for the Zn5-wheat bran and down to 1.7 for Zn40-wheat bran. We observed a rise in larval Zn content with elevated level of Zn in the wheat bran, yielding up to a maximum of 309.0 ± 0.5 mg Zn kg−1 larval dry mass for the Zn40 group (Fig. 2A). The Znlarvae/Znwheat bran ratio, however, decreased with increasing Zn concentration in the feed from 1.3 ± 0.1 for the Znbasal group down to 0.1 ± 0.0 for Zn40 feed larvae (Fig. 2C), suggesting an active regulation of Zn homeostasis within the mealworms.

Zn concentrations in the Zn-biofortified T. molitor larvae. T. molitor larvae were provided for 8 weeks with either Znbasal wheat bran or wheat bran material spiked with ZnSO4·7H2O up to fourfold of basal Zn content (see Table 1). (A) Larval Zn content determined by ICP-MS normalized to the weight of the freeze dried animals. Statistically significant differences from control are indicated (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test) (B) Total Zn intake over the feeding period was calculated from feed consumption data (see Table 2). (C) Znlarvae/Znwheat bran ratio. Data are shown as means + SEM of five replicates.

Effect of Zn-feeding on larval Cu, Fe, Mn and Cd content

Increased Zn within the larval midgut might influence the uptake, transport and distribution of other metals. Feeding of the Zn40-spiked diet did not affect the copper status of the mealworm larvae (Fig. 3A; Znbasal 20.5 ± 1.6 mg Cu kg−1 dry weight vs Zn40 18.4 ± 0.7 mg Cu kg−1 dry weight). Fe content was 78.8 ± 8.4 mg kg−1 larval dry weight in the Znbasal group. Administration of Zn40-wheat bran resulted in a decrease of larval Fe content to 59.1 ± 7.0 mg kg−1 larval dry weight (Fig. 3B; Mann–Whitney test: Fe [mg kg−1 dry weight] Znbasal vs Zn40 p < 0.01). Likewise, Mn concentrations declined when providing Zn-enriched feed (Fig. 3C; Znbasal 13.1 ± 0.7 mg Mn kg−1 dry weight vs Zn40 8.0 ± 0.4 mg Mn kg−1 dry weight; Mann–Whitney test: Znbasal vs Zn40 p < 0.001). Larval basal Cd content was 0.1 ± 0.0 mg kg−1 dry weight; almost the same as the wheat brain material (0.1 ± 0.0 mg Cd kg−1). Following feeding of the Zn40-wheat bran, 40% less Cd was detected within the L9–10 larval biomass (Fig. 3D; Mann–Whitney test: Cd [mg kg−1 dry weight] Znbasal vs Zn40 p < 0.001). Lead was not detected within the larvae, neither in the Znbasal nor in the Zn40 group.

Concentrations of Cu, Fe, Mn and Cd in Zn-biofortified T. molitor larvae. T. molitor larval material obtained from the Znbasal and Zn40 feeding groups was analyzed for (A) Cu, (B) Fe, (C), Mn and (D) Cd content. Data are shown as means + SEM of five replicates. Statistically significant differences from control are indicated (**p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; Mann–Whitney test).

Discussion

The need to find innovative sources for food and feed production has led to an increased recognition of insects2,27,28. Currently, about 92% of the ~ 2000 edible insect species worldwide is wild harvested29. However, this is no longer an option with regard to economics of food and feed production, as there is a compelling need to farm the insects in mass quantities. Consequently, present-day insect industry is looking for reliable, consistent ways to scale their production in order to compete with other sources of livestock feed while guaranteeing safety and high nutritive quality of insects2.

T. molitor L. is a promising candidate and already grown by mass rearing10,11. There are several studies examining rearing conditions and the effect of different substrates on mealworm larval development16,17,30,31. The current study confirmed the larval fitness and growth response when grown on pure wheat bran20. The estimated FCR for the Znbasal group (value 5.1) is almost identical to the one published by Melis et al. 2019 for wheat bran-fed mealworm larvae32, confirming the potency of this species to convert the bran feed into body weight of appropriate proximate composition20,32. However, dietary efficiency seems to be related to the micronutrient composition of the diet, as biomass output decreased with elevated Zn feeding. Feed avoidance due to excessive heavy metal concentrations (> 0.1% Zn2+) is common in terrestrial insects21, but was not observed in the present study. Recent observations depict the role of the Zn2+-gated midgut sensor Hodor in controlling Drosophila melanogasters food intake behavior, to ensure insect growth even under macronutrient-scarce conditions33. This mechanism, however, seems to be of minor importance in the present study, as mealworms were fed with a rather high-calorie wheat bran diet.

Developmental retardation has already been observed in Zn feeding trials with other terrestrial insects34,35. This could be the outcome of systemic Zn intoxication. Besides, Zn might restrict the systemic availability of other essential minerals in the larvaes’ midgut22,36. Like any other organism, T. molitor requires trace elements for survival. A 6 ppm zinc supplementation was established by Fraenkel37 for optimal larval growth in synthetic casein/glucose-based minimal media. Hence, feeding wheat bran material containing a total of 89.4 mg Zn kg−1 (89.4 ppm) is seemingly an excess of Zn. However, the abundance of the anti-nutritive mineral antagonist phytate in wheat bran (estimated phytate/Zn molar ratio of 66) provides a rather unfavorable matrix for intestinal Zn absorption, decreasing its Zn bioavailability38. Still, the measured total Zn content for Znbasal T. molitor larvae of around 120 mg kg−1 dry weight surpasses the wheat bran (Znlarvae/Znwheat bran ratio > 1). Accordingly, the mealworm larvae seem, at least partially, to abolish the Zn-antagonist throughout the digestion process, either by activating phytogenic phytase or phytases of gut-associated bacteria17,39. Feeding Zn-enriched wheat bran led to the intended Zn fortification of the insects, in the same order of magnitude as in a previous study40. Considering the estimated Zn-bioaccessibility upon human intestinal digestion of 40%20, an intake of ~ 30 g Zn40-freeze dried mealworms would be more than sufficient for an adult to replenish the daily zinc losses41. Due to their reduced total Fe content, consumption of Zn40-T. molitor larvae would result in lower Fe intake compared to food prepared from conventionally reared animals. Yet, the Fe content is still in excess of most other food sources, making even Zn40- larvae potentially useful for preventing Fe deficiency and contributing significantly to meeting the nutritional Fe requirements42,43. In any way, introducing Zn-biofortified mealworm larvae for use in food and feed will necessitate a copious assessment of the potential implications not just of their Fe content, but of their total macronutrient and vitamin composition as well as an examination of biological and chemical contaminants. This is crucial for avoiding long-term risks and adverse health effects for consumers5,6,7.

The Znlarvae/Znwheat bran ratio decreased inversely related to its concentration in the diet. Thus T.molitor larvae, similar to the mass rearing insect Hermetia illucens44, appear to be metal-deconcentrators45, able to adjust their internal Zn levels through homeostatic adaption of Zn absorption and excretion. Movement of Zn ions across the insect midgut epithelium, nowadays best described for the holometabolous insect D. melanogaster, requires the concerted interplay of solute carrier (SLC)39/Zrt, Irt-like protein (ZIP) Zn importers, SLC30/Zn transporter (ZnT) Zn exporters and cysteine-rich metal-binding metallothioneins (MT). Amongst the 10 ZIP and 7 ZnT proteins encoded in the Drosophila genome, the two importers dZIP42C.1 and dZIP42C.2, along with the exporter dZnT63C, are predominantly involved in dietary Zn absorption. Moreover, their expression is sensitive to both excessive and insufficient Zn supply46. Currently, 1219 insect genome-sequencing projects have been registered within the National Center for Biotechnology Information, among them 174 for Coleoptera, but the nuclear genome of T. molitor has not yet been unraveled47. According to our BLAST searches homologs of D. melanogasters dZIPs and dZnTs as well as the metal-responsive transcription factor-1 (dMTF-1) are encoded in Tenebrionidae genomes (Suppl Tables 1 and 2; Suppl Fig. 1–3). Notably, insects within this superfamily seem to lack the classical Cys-MTs, as the metal-buffering activity within midgut cells of T. molitor was shown to be mediated by other low molecular weight proteins rich in Asp/Glu48. Elucidating the expression, activity and tissue distribution of all these proteins during the lifecycle of T. molitor would not only contribute to the overall knowledge on Zn homeostasis in insects, but particularly provide decisive advances when aiming to raise the mealworm Zn enrichment quota by implementing Zn transporter-targeted strategies into rearing49.

Cu, Mn, and Fe contents of T. molitor larvae grown on non-spiked wheat bran were close to values reported for mealworm larvae in other feeding trials19,50, underlining the micronutrient quality of the applied bran material. Yet, the metals were differently impacted by Zn-biofortification. The Cu status of the mealworms remained stable, irrespective of Zn dosing. This is contrary to the situation in mammals, where prolonged high Zn feeding causes systemic copper-deficiency, possibly due to overexpression of intestinal apo-MT retaining the copper ions inside the enterocytes51. Insect midgut function seems to be strictly regionalized52,53. Cu uptake occurs primarily within the so-called “copper cell region”, where, at least in D. melanogaster, Zn was shown to slightly colocalize33,54. Nevertheless, the bivalent Zn2+ does not compete with cellular Cu uptake via the high-affinity Cu+ transporter Ctr155. Cellular Zn-sensing by the metal regulatory transcription factor MTF-1 is critical with regard to triggering the expression of Zn-sensitive genes (e.g., metallothionein genes) in any species—including insects56. In addition to its conserved zinc fingers within the DNA-binding domain D. melanogaster MTF-1 contains a unique C-terminal cysteine-enriched copper-cluster that allows specific intracellular copper monitoring; consequently dMTF-1 keeps the cellular metallothionein gene transcription low under limited Cu supply and enhanced upon copper overload57. A homologous Cu-cluster sequence is present in the predicted protein of the beetle Tribolium castaneum, wheras Asbolus verrucosus MTF-1 is C-terminally truncated, thus missing this domain (Suppl Fig. 3). The outcome of the 1KITE (1 K Insect Transcriptome Evolution) and the “i5k” (Sequencing Five Thousand Arthropod Genomes)58 initiative will soon provide insight into the regulation of Zn and Cu homeostasis in several other insects designated for food/feed production.

The reduction in total Fe and Mn content in the Zn40 larvae is probably due to a competition with Zn for intestinal transporters at the site of absorption. Malvolio (Mvl), an insect homolog of the divalent metal ion transporter 1 (DMT1), is the likeliest candidate for the luminal uptake of Fe2+and Mn2+ 59 in the mealworm midgut (see Suppl Table 2). Although Zn2+ is a rather weak Mvl substrate60, there might be a competition with the aforementioned metal ions, especially under massive nutritional Zn excess. Accordingly, a Zn/Fe/Mn-mixed co-supplementation strategy during mealworm rearing would be a worthwhile option when aiming to counterbalance the other trace element delivery quotas while simultaneously enhancing larval growth/biomass output.

As T. molitor larvae are aimed to be rated as novel food or feed, further quality and safety concerns should be addressed and strictly monitored in addition to their macro- and micronutrient content. In fact, insects might accumulate hazardous chemicals during growth, amongst them heavy metals that may pose a risk to humans or animals7,61. As a natural resource, grain material varies considerably in its elemental composition, which is also reflected in slightly different toxic metal contents in T. molitor within various studies61. The EU maximum level for Cd in complete feed for farm animals has been set at 0.5 mg kg−1 (relative to a moisture content of 12%)62. From a safety perspective, the mealworm larvae grown on Znbasal wheat bran in the present study would be acceptable for feed application, consistent with results of other studies using the same feeding substrate63,64. Insects intended for human consumption in Europe are covered by the Novel Food Regulation EU 2015/22833, and must therefore be authorized by EU institutions61. The EU “ALARA" (as low as reasonably achievable policy) precautionary principle becomes relevant when setting maximum limits for contaminants, including heavy metals, in foodstuff for public health protection purposes (Regulation 315/93/EEC65). The introduction of Zn-enriched wheat bran material into mealworm breeding is certainly an effective strategy to reduce the amount of the human/animal toxicant Cd within the mealworm larvae. Zn-competitive transport routes for cellular Cd uptake in insects were already discussed66, yet their molecular identity and mechanisms need to be clarified when intending to further target the Cd burden of insects during rearing. Aside from interfering with the uptake of this toxic element, Zn triggers synthesis of the aforementioned MT-like proteins within the midgut epithelium, providing a stable pool of midgut Cd-trapping molecules. In fact, these proteins were described to be released into the feces during cell gut renewal44,48,63, explaining the decreased mealworm larval Cd bioaccumulation factor observed in the present study. As a substantial part of Cd enters the cells via Ca2+ channels67, it might be useful to include this macromineral in future mealworm enrichment strategies. Here, Zn/Fe/Cu/Mn/Ca-supra-supplemented wheat bran should provide an ideal trace element composition when aiming to produce mealworm larvae enriched in multiple essential micronutrients and low in toxic metals, which is worthwhile to be tested and introduced into T. molitor rearing on an industrial scale.

Conclusion

Global population growth will increasingly challenge the food industry in the coming years. The yellow mealworm (T. molitor) is a sustainable alternative source to animal-derived protein and lipids, suitable for mass rearing and large-scale industrial production. Yet, the industrial technology needs to be optimized and standardized to process the insects in the best possible way, from an economic, food/feed safety and nutritive point of view. Summarizing this study’s results, a Zn-spiked wheat bran feeding strategy is an easy and inexpensive approach to produce T. molitor valorized in its content of the essential micronutrient Zn. Zn-biofortification led to a moderate Fe and Mn reduction in mealworms, reflected in reduced feed conversion efficiency. Nevertheless this can easily be counteracted in the future by Fe/Mn co-supplementation. Importantly, Zn-enriched rearing reduced the levels of the human/animal toxicant Cd within the mealworm larvae, a technological novelty of outstanding importance to be implemented in the future production process to ensure the consumer safety of this edible insect species. Overall, these results provide relevant insight for the development of optimized strategies to process T. molitor in the future, both in terms of nutrient quality and quantity.

Materials and methods

Materials and chemicals

Wheat bran/wheat flour (Roland Mills Nord GmbH & Co. KG, Bremen, Germany); H2O2 (Sigma Aldrich, Munich, Germany); HNO3 (Sigma Aldrich, Munich, Germany); Indium Standard for ICP-MS TraceCERT (Sigma Aldrich, Munich, Germany); Multielement Standard Solution 6 for ICP TraceCERT (Sigma Aldrich, Munich, Germany); Rhodium ICP-MS Standard TraceCERT (Sigma Aldrich, Munich, Germany); ZnSO4∙7H2O (Sigma Aldrich, Munich, Germany).

Experimental design

T. molitor beetles of University of Applied Sciences Bremerhaven own breeding were placed on wheat flour for oviposition (see Fig. 1). After 7 days, the eggs were removed from the laying substrate with a fine-mesh sieve (1 mm mesh size) and placed in the breeding container. Freshly hatched larvae were allowed to grow in the wheat bran substrate. 6 weeks post hatching T. molitor larvae (stage L3–4, average starting weight 1.23 ± 0.01 mg) were seeded into 400 ml glass beakers on Zn-spiked wheat bran feed (Znbasal to Zn40fold basal; further details for wheat bran preparation are provided in the “feed spiking” section). Each Zn treatment was performed in 5 biological replicates, where each replicate comprised 60 mealworm larvae in a density of 142 larvae/dm2 growth surface. All beakers were incubated at 27 °C with a humidity of 75% with no day/night rhythm for light, temperature and humidity for an 8 week period68. Each feeding group was fed as soon as the feed in the beaker had been consumed, with a total of 20 g feed over the whole feeding period. The exact amount of feed supply and feces production was recorded separately for every larval replicate. After harvesting at day 98 post hatching, the number and larval weight of living L9–10 animals was registered to assess the growth performance and feed utilization. Prior to metal analysis, larvae were starved for 24 h to diminish gastrointestinal feed residues. Following freeze-drying in a Christ Beta 1–8 LD Plus freeze dryer (Martin Christ, Osterode am Harz, Germany)20 all samples were stored at − 20 °C.

Feed spiking

Wheat bran already contains micronutrients, including Zn. Thus the basal Zn content of this study’s wheat bran batch was evaluated prior to spiking. To this end, 500 mg wheat bran samples were subjected to a microwave-assisted digestion (Mars 6, CEM GmbH, Kamp-Lintfort, Germany) with a 1:1 mixture of ultrapure HNO3 (65%) and H2O2 (30%). Zn content was analyzed by flame atomic absorption spectrometry (FAAS) on a Perkin Elmer AAnalyst 800 (Perkin Elmer, Rodgau, Germany) applying an external calibration (analytical parameters: LOD 10.3 µg Zn/l; LOQ 15.9 µg Zn/l;20). Based on these values, spiking of 500 g wheat bran samples with ZnSO4·7H2O pre-solved in 50 ml 18.2 MΩ·cm water (Millipore Milli-Q Water Purification System) was then performed to reach the desired final Zn biomass concentration ranging between 89.4 mg/kg wheat bran (Znbasal) to a maximum of 3577.5 mg/kg wheat bran (Zn40fold basal) (see Table 2).

Larval growth performance and feed utilization parameters

Larval growth performance was evaluated based on the larval fresh weight and the survival rate (SR, Eq. 1) of L9–10 animals.

Larval weight data from the end (stage L9–10) and the beginning (stage L3–4) of the feeding period along with total feed consumption (FC, Eq. 2) were further used to calculate the efficiency of ingested feed conversion (ECI, Eq. 3) and the feed conversion ratio (FCR; feed input per unit of fresh product; Eq. 4) on fresh matter basis16,31,69.

Feed assimilation rate (FA, Eq. 5) was used to evaluate the efficiency of digested feed conversion (ECD; Eq. 6;16,69)

Trace element analyses of mealworm larvae

Larval materials were grinded replica-wise and portioned before heating in a laboratory microwave digester (Mars 6, CEM GmbH, Kamp-Lintfort, Germany) in a 3:1 mixture of ultrapure HNO3 (65%) and H2O2 (30%) containing 500 µg/L indium as an internal standard to estimate metal recovery rates. After digestion the samples were prediluted to 5 ml using 18.2 MΩ·cm water (Millipore Milli-Q Water Purification System). For Zn, Cu, Mn and Cd quantification samples were further diluted 1:100 in 0.65% HNO3 containing 5 µg/L rhodium and analyzed on an Elan DRC II inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometer (PerkinElmer LAS GmbH, Rodgau, Germany). For Fe quantification, 1:500 prediluted samples were analyzed in DRC mode using methane as reaction gas. Further ICP-MS conditions are listed in Table 3. The instrument was tuned daily for maximum sensitivity (< 0.03 oxide ratio (140Ce+ 16O/140Ce+), double charged ratio < 0.03 (137Ba++/137Ba+) and background counts < 2 cps).

Statistical analyses

Statistical significance of the experimental results was analyzed by either Mann–Whitney U test or one-way ANOVA/Dunnett’s post hoc test using GraphPad prism software version 8.02 (GraphPad Software Inc., CA, USA).

References

United Nations. in Work. Pap. No. ESA/P/WP.241 (2015).

van Huis, A. Prospects of insects as food and feed. Org. Agric. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13165-020-00290-7 (2020).

EU. Regulation (EU) 2015/2283 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 November 2015 on novel foods, amending Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council and repealing Regulation (EC) No 258/97 of the European Parliament and of the Council and Commission Regulation (EC) No 1852/2001; EU: Brussels, Belgium, 2015.

EU. Commission Regulation (EU) 2017/893 of 24 May 2017 Amending Annexes I and IV to Regulation (EC) No 999/2001 of the European Parliament and of the Council and Annexes X, XIV and XV to Commission Regulation (EU) No 142/2011 as Regards the Provisions on Proc. (2017).

Dobermann, D., Swift, J. A. & Field, L. M. Opportunities and hurdles of edible insects for food and feed. Nutr. Bull. 42, 293–308 (2017).

Lähteenmäki-Uutela, A. et al. The impact of the insect regulatory system on the insect marketing system. J. Insects Food Feed 4, 187–198 (2018).

EFSA. Risk profile related to production and consumption of insects as food and feed. EFSA J. 13, 2 (2015).

Finke, M. D., Rojo, S., Roos, N., van Huis, A. & Yen, A. L. The European Food Safety Authority scientific opinion on a risk profile related to production and consumption of insects as food and feed. J. Insects Food Feed 1, 245–247 (2015).

Rumpold, B. A. & Schlüter, O. K. Nutritional composition and safety aspects of edible insects. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 57, 802–823 (2013).

Grau, T., Vilcinskas, A. & Joop, G. Sustainable farming of the mealworm Tenebrio molitor for the production of food and feed. Zeitschrift fur Naturforsch. Sect. C J. Biosci. 72, 337–349 (2017).

Varelas, V. Food wastes as a potential new source for edible insect mass production for food and feed: A review. Fermentation 5, 81 (2019).

Kröncke, N. et al. In African Edible Insects As Altern Source Food, Oil Protein Bioact. Components (ed. Mariod, A. A.) 123–139 (Springer International Publishing, Berlin, 2020).

Prückler, M. et al. Wheat bran-based biorefinery 1: Composition of wheat bran and strategies of functionalization. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 56, 211–221 (2014).

Cortes Ortiz, J. A. et al. In Insects as Sustain Food Ingredients (eds Dossey, A. T. et al.) 153–201 (Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2016).

Morales-Ramos, J. A., Rojas, M. G., Shapiro-Ilan, D. I. & Tedders, W. L. Self-selection of two diet components by tenebrio molitor (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae) larvae and its impact on fitness. Environ. Entomol. 40, 1285–1294 (2011).

Morales-Ramos, J. A. & Rojas, M. G. Effect of larval density on food utilization efficiency of Tenebrio molitor (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae). J. Econ. Entomol. 108, 2259–2267 (2015).

Mancini, S. et al. Former foodstuff products in Tenebrio molitor rearing: Effects on growth, chemical composition, microbiological load, and antioxidant status. Animals 9, 2 (2019).

Shapiro-Ilan, D., Rojas, M. G., Morales-Ramos, J. A., Lewis, E. E. & Tedders, W. L. Effects of host nutrition on virulence and fitness of entomopathogenic nematodes: Lipid-and protein-based supplements in Tenebrio molitor diets. J. Nematol. 40, 13–19 (2008).

Mwangi, M. N. et al. Insects as sources of iron and zinc in human nutrition. Nutr. Res. Rev. 31, 248–255 (2018).

Kröncke, N. et al. Effect of different drying methods on nutrient quality of the yellow mealworm (Tenebrio molitor L.). Insects 10, 84 (2019).

Mogren, C. L. & Trumble, J. T. The impacts of metals and metalloids on insect behavior. Entomol. Exp. Appl. 135, 1–17 (2010).

Sandstroem, B. Micronutrient interactions: Effects on absorption and bioavailability. Br. J. Nutr. 85, S181–S185 (2001).

Himeno, S., Sumi, D. & Fujishiro, H. Toxicometallomics of cadmium, manganese and arsenic with special reference to the roles of metal transporters. Toxicol. Res 35, 311–317 (2019).

Lemos, D. & Tacon, A. G. J. Use of phytases in fish and shrimp feeds: A review. Rev. Aquac. 9, 266–282 (2016).

Gibson, R. S., King, J. C. & Lowe, N. A review of dietary zinc recommendations. Food Nutr. Bull. 37, 443–460 (2016).

Stevenson, L., Phillips, F., Osullivan, K. & Walton, J. Wheat bran: Its composition and benefits to health, a European perspective. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 63, 1001–1013 (2012).

Mikołajczak, Z., Rawski, M., Mazurkiewicz, J., Kierończyk, B. & Józefiak, D. The effect of hydrolyzed insect meals in sea trout fingerling (Salmo trutta m. trutta) diets on growth performance, microbiota and biochemical blood parameters. Animals 10, 1–20 (2020).

Benzertiha, A. et al. Tenebrio molitor and Zophobas morio full-fat meals as functional feed additives affect broiler chickens’ growth performance and immune system traits. Poult. Sci. 99, 196–206 (2020).

Yen, A. L. Insects as food and feed in the Asia Pacific region: Current perspectives and future directions. J. Insects as Food Feed 1, 33–55 (2015).

Fasel, N. J., Mene-Saffrane, L., Ruczynski, I., Komar, E. & Christe, P. Diet induced modifications of fatty-acid composition in mealworm larvae (Tenebrio molitor). J. Food Res. 6, 22–31 (2017).

Oonincx, D. G. A. B., Van Broekhoven, S., Van Huis, A. & Van Loon, J. J. A. Feed conversion, survival and development, and composition of four insect species on diets composed of food by-products. PLoS ONE 10, 1–20 (2015).

Melis, R. et al. Metabolic response of yellow mealworm larvae to two alternative rearing substrates. Metabolomics 15, 1–13 (2019).

Redhai, S. et al. An intestinal zinc sensor regulates food intake and developmental growth. Nature 580, 263–268 (2020).

Gintenreiter, S., Ortel, J. & Nopp, H. J. Effects of different dietary levels of cadmium, lead, copper, and zinc on the vitality of the forest pest insect Lymantria dispar L. (Lymantriidae, Lepid). Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 25, 62–66 (1993).

Noret, N. et al. Development of Issoria lathonia (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) on zinc-accumulating and nonaccumulating Viola species (Violaceae). Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 26, 565–571 (2007).

Nishito, Y. & Kambe, T. Absorption mechanisms of iron, copper, and zinc: An overview. J. Nutr. Sci. Vitaminol. 64, 1–7 (2018).

Fraenkel, G. S. the effect of zinc and potassium in the nutrition of Tenebrio molitor, with observations on the expression of a carnitine deficiency. J. Nutr. 65, 361–395 (1958).

Maret, W. & Sandstead, H. H. Zinc requirements and the risks and benefits of zinc supplementation. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 20, 3–18 (2006).

Guo, J. et al. Activation of endogenous phytase and degradation of phytate in wheat bran. J. Agric. Food Chem. 63, 1082–1087 (2015).

Bednarska, A. J. & Świątek, Z. Subcellular partitioning of cadmium and zinc in mealworm beetle (Tenebrio molitor) larvae exposed to metal-contaminated flour. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 133, 82–89 (2016).

Haase, H., Ellinger, S., Linseisen, J., Neuhäuser-Berthold, M. & Richter, M. Revised D-A-CH-reference values for the intake of zinc. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtemb.2020.126536 (2020).

EFSA. Dietary reference values for nutrients summary report. EFSA J 14, 2 (2017).

Institute of Medicine of the National Academmies. Dietary Reference Intakes: The Essential Guide to Nutrient Requirements Dietary Reference Intakes DRI (The National Academies Press, Washington, 2006).

Diener, S., Zurbrügg, C. & Tockner, K. Bioaccumulation of heavy metals in the black soldier fly, Hermetia illucens and effects on its life cycle. J. Insects Food Feed 1, 261–270 (2015).

Dallinger, R. Strategies of metal detoxification in terrestrial invertebrates. Ecotoxicol. Met. Invertebr. 2, 245–289 (1993).

Xiao, G. & Zhou, B. What can flies tell us about zinc homeostasis?. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 611, 134–141 (2016).

Li, F. et al. Insect genomes: Progress and challenges. Insect Mol. Biol. 28, 739–758 (2019).

Pedersen, S. A., Kristiansen, E., Andersen, R. A. & Zachariassen, K. E. Isolation and preliminary characterization of a Cd-binding protein from Tenebrio molitor (Coleoptera). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. C Toxicol. Pharmacol. 145, 457–463 (2007).

Hashimoto, A. et al. Soybean extracts increase cell surface ZIP4 abundance and cellular zinc levels: A potential novel strategy to enhance zinc absorption by ZIP4 targeting. Biochem. J. 472, 183–193 (2015).

Simon, E., Baranyai, E., Braun, M., Fábián, I. & Tóthmérész, B. Elemental concentration in mealworm beetle (Tenebrio molitor L.) during metamorphosis. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 154, 81–87 (2013).

Reeves, P. G., Rossow, K. L. & Bobilya, D. J. Zinc-induced metallothionein and copper metabolism in intestinal mucosa, liver, and kidney of rats. Nutr. Res. 13, 1419–1431 (1993).

Marianes, A. & Spradling, A. C. Physiological and stem cell compartmentalization within the Drosophila midgut. Elife 2013, 2 (2013).

Caccia, S., Casartelli, M. & Tettamanti, G. The amazing complexity of insect midgut cells: Types, peculiarities, and functions. Cell Tissue Res. 377, 505–525 (2019).

Jones, M. W. M., De Jonge, M. D., James, S. A. & Burke, R. Elemental mapping of the entire intact Drosophila gastrointestinal tract. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 20, 979–987 (2015).

Lee, J., Petris, M. J. & Thiele, D. J. Characterization of mouse embryonic cells deficient in the Ctr1 high affinity copper transporter: Identification of a Ctr1-independent copper transport system. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 40253–40259 (2002).

Günther, V., Lindert, U. & Schaffner, W. The taste of heavy metals: Gene regulation by MTF-1. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 1823, 1416–1425 (2012).

Günther, V., Waldvogel, D., Nosswitz, M., Georgiev, O. & Schaffner, W. Dissection of Drosophila MTF-1 reveals a domain for differential target gene activation upon copper overload vs. copper starvation. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 44, 404–411 (2012).

Consortium, I. The i5K initiative: Advancing arthropod genomics for knowledge, human health, agriculture, and the environment. J. Hered. 104, 595–600 (2013).

Vá Squez-Procopio, J., Osorio, B., Corté S-Martí Nez, L., Herná Ndez-Herná Ndez, F., Medina-Contreras, O., Rí Os-Castro, E., Comjean, A., Li, F., Hu, Y., Mohr, S., Perrimon, N. & Missirlis, F. Intestinal response to dietary manganese depletion in Drosophila †. Metallomics 12, 218–240 (2020).

Southon, A., Farlow, A., Norgate, M., Burke, R. & Camakaris, J. Malvolio is a copper transporter in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Exp. Biol. 211, 709–716 (2008).

Schrögel, P. & Wätjen, W. Insects for food and feed-safety aspects related to mycotoxins and metals. Foods 8, 1–28 (2019).

EU. Directive 2002/32/EC of The European Parliament and of the Council of 7 May 2002 on Undesirable Substances in Animal Feed; EU: Brussels, Belgium, 2002.

Van Der Fels-Klerx, H. J., Camenzuli, L., Van Der Lee, M. K. & Oonincx, D. G. A. B. Uptake of cadmium, lead and arsenic by Tenebrio molitor and Hermetia illucens from contaminated substrates. PLoS ONE 15, e0166186 (2016).

Truzzi, C. et al. Influence of feeding substrates on the presence of toxic metals (Cd, pb, ni, as, hg) in larvae of Tenebrio molitor: Risk assessment for human consumption. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 16, 4815 (2019).

EU. Council Regulation (EEC) No 315/93 of 8 February 1993 Laying down Community Procedures for Contaminants in Food; EU: Brussels, Belgium, 1993.

Poteat, M. D. & Buchwalter, D. B. Calcium uptake in aquatic insects: Influences of phylogeny and metals (Cd and Zn). J. Exp. Biol. 217, 1180–1186 (2014).

Janssens, T. K. S., Roelofs, D. & van Straalen, N. M. Molecular mechanisms of heavy metal tolerance and evolution in invertebrates. Insect Sci. 16, 3–18 (2009).

Niermans, K., Woyzichovski, J., Kröncke, N., Benning, R. & Maul, R. Feeding study for the mycotoxin zearalenone in yellow mealworm (Tenebrio molitor) larvae—investigation of biological impact and metabolic conversion. Mycotoxin Res. 35, 231–242 (2019).

Waldbauer, G. P. The consumption and utilization of food by insects. Adv. In Insect Phys. 5, 229–288 (1968).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Cathrin Schröder for excellent technical assistance. This project is supported via the German Federation of Industrial Research Associations (AIF-27 LN/1) within the program of promoting the Industrial Collective Research (IGF) of the German Ministry of Economics and Energy (BMWi), based on a resolution of the German Parliament. The work of MM is funded by a Postdoc Grant from the Berlin Institute of Technology.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: C.K., N.K.; data curation: C.K., M.M., N.K.; formal analysis: C.K., M.M.; funding acquisition: H.H. and R.B.; investigation: C.K., M.M., N.K.; project administration: C.K.; resources: H.H., R.B.; supervision: H.H., C.K., R.B.; writing—original draft: C.K., M.M. writing—review and editing: C.K., M.M., N.K., R.B., H.H. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Keil, C., Maares, M., Kröncke, N. et al. Dietary zinc enrichment reduces the cadmium burden of mealworm beetle (Tenebrio molitor) larvae. Sci Rep 10, 20033 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-77079-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-77079-x

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.