Abstract

There has been tritium groundwater leakage to the land side of Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plants since 2013. Groundwater was continuously collected from the end of 2013 to 2019, with an average tritium concentration of approximately 20 Bq/L. Based on tritium data published by Tokyo Electric Power Company Holdings (TEPCO) (17,000 points), the postulated source of the leakage was (1) leaks from a contaminated water tank that occurred from 2013 to 2014, or (2) a leak of tritium that had spread widely over an impermeable layer under the site. Based on our results, sea side and land side tritium leakage monitoring systems should be strengthened.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Fukushima Dai-ichi Nuclear Power Plant (FDNPP) accident released a large amount of radioactive materials into the environment since 2011. Most were in the gaseous state, released primarily through the atmosphere to the land of eastern Japan and to the north-west Pacific Ocean. The released amount was estimated to be approximately 520 PBq1, with radioactive iodine (mainly 131I), radioactive cesium (134Cs, 137Cs), and noble gases such as 133Xe accounting for most of the released amount. Tritium (3H, T1/2 12.3 y.) was an additional part of the radioactive materials released, but is considered as a “soft”, or low energy, beta emitter. The tritium beta energy is low (max 18.6 keV), and requires large quantities to deliver significant radiation doses, so that the measurement of other nuclear species was prioritized when considering human protection immediately following the accident. Therefore, data on tritium in the environment after the FDNPP accident are still limited in Japan2,3.

Tritium in a boiling water reactor is mainly produced by ternary fission. At FDNPP, 8.51 × 1013 Bq/month at 1.1 MW operation was produced by ternary fission4. Tritium is also produced in reactors by 10B(n, 2α)3H, 10B(n, α)7Li, 7Li(n, α)3H, or 6Li(n, α)3H, 2H(n, γ)3H5.

Cumulate 3H yields in the reactors at FDNPP have been estimated to range from 0.01% to 0.0108%6,7. According to estimates made immediately after the accident in 2011, there were reports that the inventory of 3H at the time of the accident was 1.81 × 1013 Bq8, but according to recent reports by Tokyo Electric Power Company Holdings (TEPCO), the inventory of 3H immediately after the accident was estimated to be 1.0 × 1015 Bq at Unit 1, 1.2 × 1015 Bq at Unit 2, and 1.2 × 1015 Bq at Unit 3, for a total of 3.4 × 1015 Bq4. As of March 24, 2016, 7.6 × 1014 Bq was in the storage tanks at the FDNPP site, 2.7 × 1013 Bq in the reactor building(R/B), and estimated 1.8 × 1015 Bq was released outside the reactor or in debris (Table 1)9,10.

There are three possible pathways for the release of 3H from FDNPP to the outside: ocean, atmosphere, and groundwater. Among them, direct releases to the ocean and releases to the atmosphere have been reported in detail.

An estimated 0.1–0.5 PBq of 3H flowed into the north Pacific Ocean from the accident6,11. Tritium was detected in the north-west Pacific Ocean off the coast of Hirono town, Fukushima Prefecture 1 month after the accident12.

Investigation of 3H in precipitation may be one of the easiest ways to confirm the release of 3H into the atmosphere. The highest tritium concentration in precipitation was estimated 10 days after the accident at 1342 TU (equivalent to 158 Bq/L)13. A surface water concentration of 3H at 184 (± 2) Bq/L was detected in rice paddy fields at 1.5 km from the FDNPP plant12. Since both reports greatly exceeded the natural 3H level in Japan (1.1–7.8 TU, equivalent to 0.13–0.92 Bq/L) or 6 TU (equivalent to 0.71 Bq/L)2,14, there was no doubt that the 3H was from the FDNPP accident. Also, since the samples were collected approximately 1 month after the accident, the 3H on the ground most likely originated as precipitation from the atmosphere, not via groundwater.

Leaking of 3H through groundwater is difficult to analyze. In this study, we report that 3H above natural levels has been detected continuously in groundwater sampled from 2013 to 2019 on land approximately 30 m from the FNDPP site boundary. A key aspect of this study is that the water examined was groundwater, not surface water. To reveal the hydrogeological origin of the groundwater sources, Sr isotope ratio (87Sr/86Sr) was also measured as a natural tracer of water–rock interaction and ground water mixing patterns15,16,17,18.

From 2013 to 2019, several countermeasures have been taken at the FDNPP to prevent contaminated groundwater from leaking off site. The relevance will be discussed, including the results of detailed tritium measurements in the water collected inside/outside FDNPP site.

Results

Outflow of 3H into groundwater from FDNPP

Most of the tritium present in the FDNPP was assumed to have been produced by ternary fission. As long as no re-criticality occurs, no new tritium is produced. However, it is estimated that there is 1.8 × 1015 Bq of tritium that has not been identified in the turbine buildings and in contaminated water, in addition to the amount released outside after the accident or the amount in debris10. In Japan, the limit for tritium release into the ocean is 6.0 × 104 Bq/L in a typical nuclear facility, but in the case of the FDNPP, 1500 Bq/L is the regulatory limit for tritium effluent19. Therefore, over 1.2 × 1012 L of water would be required for dilution.

Figure 1 shows a schematic diagram of the nuclear power plant site after the accident.

The land-side water impermeable wall (frozen soil wall) and the sea-side water impermeable wall (steel sheet pile) were installed to surround the circumference of the FDNPP and prevent 3H flow off site. Frozen soil walls block uncontaminated groundwater from getting close to reactors and buildings, while steel sheet piles block potentially contaminated groundwater from spreading into the ocean.

A series of wells were drilled at 35 m above sea level, upstream of FDNPP, to reduce the amount of groundwater flowing under the reactor building, and the well water was constantly pumped (Ground water bypass). The wells were drilled to a depth directly above an impermeable layer inside the plant's grounds. Figure 2 shows the radioactivity of tritium in groundwater flowing through this bypass from June 2014 to June 2019. The ground water bypass system has 12 wells (No.1 to No.12)20, and the highest concentration of radioactivity was in No. 10 well on the south side. The concentration of 3H on June 2014 was 10 Bq/L, but it exceeded 3000 Bq/L in April 2016 and has been gradually decreasing since then to approximately 1400 Bq/L in 2019. No. 10 well is next to No.11, which also had levels of 3H higher than other wells, at 700 Bq/L as of June 11, 2019. No. 12 is the southernmost well, but unlike No. 10 and No. 11 wells, the tritium levels tended to decrease monotonically from a peak in April 201421.

3H radioactivity in water collected from wells that facilitate ground water bypass of the FDNPP. The location of wells is shown in Fig. 1.

Groundwater was estimated to flow into the ocean from the mountain side based on ground water flow modeling22.

It was not possible to determine from these data whether tritium-contaminated groundwater was still being released as tritium had already spread before the completion of the several barriers. Contaminated water may still be leaking from FDNPP site even after the barrier was completed23. The fact that tritium has been continuously detected in groundwater from the bypass installed upstream of FDNPP even after the completion of the water barrier (frozen wall) does not mean that tritium in the groundwater flows to the sea. In addition, the radioactivity trends in the neighboring wells vary widely, indicating that groundwater is moving in a complex manner.

The movement of groundwater may be impacted by the removal of the water from the wells. The amount of water removed from the wells has been changed in a timely manner in order to maintain appropriate groundwater level. If the water level was lowered too much, water flow would be induced from the reactor.

In order to evaluate the absolute amount of tritium contained in well water, information such as flow rate would be required, but TEPCO has not disclosed flow rates publicly.

3H radioactivity leakage

The concentration of 3H in the sump water collected at the sites indicated by asterisks in Fig. 3 is shown in Fig. 4. The 3H observed in sump water ranged from 15 to 31 Bq/L and was almost constant (average 20 Bq/L). The 3H exceeded the expected natural level (up to 7.8 TU(1 TU = 0.118 Bq/L), 0.92 Bq/L) of 3H, thus it is assumed that the 3H originated from FDNPP. Since the sump water were collected directly from cliffs, tritium in sump water would have passed under the ground of FDNPP site.

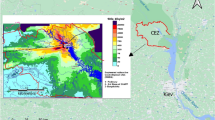

Bird’s eye view of FDNPP from south side. The sump water sampling point was the under the cliff (*), at 17 m above the sea level. The sump water which flowed out from the plastic pipe which stuck in the wall was sampled directly. Sump water was also identified on the shoreline (**). There is a river running on the south side that reaches the north-west Pacific Ocean. This map was created by processing an electronic topographic map by Geospatial information authority of Japan.

Tritium in sump water collected under the cliff at the boundary of the FDNPP shown in Fig. 3 (single asterisk. *).

In addition, the sump water also contained radiocesium (134Cs and 137Cs). The concentration of 137Cs ranged from 3 to 4 Bq/kg, and the ratio of 134Cs/137Cs radioactivity at the time of the accident was almost 1. This also suggests that the water originated from FDNPP site24.

Tritium deposited via the air in surface water is not expected to mix with ground water. No tritium exceeding natural levels was detected in the air and precipitation around the FDNPP during the study period (2013–2019). At the FDNPP, four measures have been taken to prevent surface water from infiltrating into groundwater25..

-

1.

Grouting of surfaces (to prevent from soaking rainwater into the ground) (from Oct. 2014),

-

2.

Pumping of water from the sub-drain (from Sep. 2015),

-

3.

Frozen soil wall around the 4 nuclear plants (from Mar. 2016),

-

4.

Sea-side impermeable wall (from Oct. 2015).

It was clear that there was no direct correlation with the radioactivity of tritium contained in the leachate compared with the respective construction periods.

No tritium above the natural level was detected in the flowing-wells about 500 m away from the nuclear power plant. (see supplementary data).

The flowing-well water tritium concentration ranged from 0.003 to 0.01 Bq/L and was measured using the ingrowth method. Natural level of 3H in Japan was ranged from 0.13–0.92 Bq/L. Meanwhile the radioactivity of tritium in flowing water was below 0.01 Bq/L. The radioactivity of the water was at least one eighth. It was considered to be at least three half-lives above conservative estimates. Therefore, it was estimated that the tritium in the groundwater from the flowing-well had an age of nearly 40 years.

Discussion

Relationship between countermeasures and contaminated water

Tritium released into the north-west Pacific Ocean by FDNPP as liquid prior to the accident was reported as 2.0 × 1012 Bq in 2009, 1.6 × 1012 Bq in 2008, 1.4 × 1012 Bq in 200726. These tritium releases were legal and planned. Quantitatively, and in comparison, the amount of leakage noted in this research may not be a major problem.

However, it is important to note that there is a route of tritium groundwater leakage on the land-side from the inside to the outside of the site. There may be further leakage in the future. We postulate three scenarios where leakage could occur in the future.

First, there is a possibility that surface water has infiltrated the groundwater. The river water within a 1 km radius around the site in Fig. 3 was sampled and analyzed for 3H during the study period, but 3H above the natural level was never detected. Therefore, the first possibility was not demonstrated.

Second, there was a possibility of leakage from a group of tanks just above the cliff. In August 2013 in the H4 area and in February 2014 in the H6 area, contaminated water leaked from the tanks to the ground. In the H4 area, outflow was reported to be 8.4 × 107 Bq/L (total beta) over about 300 m3, with most of the water infiltrating the ground27. In the H6 area, 3.0 × 106–2.3 × 108 Bq/L (total beta) leaked into to about 100 m328. The radioactivity of tritium in water pumped from observation wells around the H4 (E1-E14, wellpoint, F1 well) and H6 areas (G1-G3 well) are shown in Fig. 5a,b, respectively. The time of leakage from the contaminated water tank was indicated by the red arrow (Fig. 5a,b). In the H4 area, tritium contained in the E1 well was highest (790 kBq/L, Oct 17th, 2013). After 2013, radioactivity in the E1 well-tended to decrease gradually.

(a) Radioactivity of 3H in well (E1 to E14, well-point, F1) water around H4 area (inside the plant site). The red arrow indicates when the leak occurred from the tanks. (b) Radioactivity of 3H in well (G1–G3) water around H6 area (inside the plant site). The red arrow indicates when the leak occurred from the tanks.

A well near the leaking tank (E1, E10) had higher tritium activity than other wells. Therefore, it is possible that tritium leaked from the tank and was continuously mixed into the well water. On the other hand, there was no clear correlation between tritium in wells in the H6 area and leakage. It is possible that the H6 tank leaked water may not have reached the well water in the H6 area yet.

The possibility cannot be ruled out that the contaminated water gradually spread underground and eventually leaked off site. Although no direct evidence of this and of spillage outside the site has been found, there was a possibility that tritium soaked underground due to accidental spills from tanks in 2013 and 2014 and was leaking directly off the site.

Third, groundwater may be spreading horizontally over the impermeable layer below the FDNPP. As shown in Fig. 2 and Fig. 5a,b, tritium has been widely detected in wells at the FDNPP. Therefore, it was reasonable to assume that tritium was seeping from the point where the impermeable layer was cut off by the cliff at the site boundary. However, while tritium radioactivity in the leachate was always constant, there is insufficient data for determining if the tritium is moving along the impermeable layer.

The tritium detected under the cliff was not exceptionally high, but it appears that a hydrologic route has been established for the tritium to leak via underground pathways off site. If a new earthquake or tsunami occurs, more highly contaminated water may flow out though the route. The monitoring system on the land side is very vulnerable and needs to be improved.

The origin of tritium-containing water

The discussions so far have made it clear that tritium is leaking out of the impermeable layer on the cliffs of the FDNPP. Strontium isotope ratio (87Sr/86Sr) analysis was carried out to determine whether the water was widely spread on the south side of the plant. A comparison of strontium between water collected at the cliff (* in Fig. 3) and spring water collected at the shoreline (** in Fig. 3) was performed to ascertain if a hydrologic connection between the two sites exists. The results are presented in Table 2. Sr concentrations were not specific at 185 and 121 ppb at the site * and at the site **, respectively. However, when comparing the 87Sr/86Sr ratios of groundwater at the two sites, the two have distinctly different values over the uncertainty on the Sr isotopic analysis. The difference is more visible if the results are normalized to NIST-987 strontium carbonate isotopic standard (standard value of 87Sr/86Sr is 0.710248)29. For this purpose, the “delta notation” has been applied as per following:

The obvious divergence of the delta notations reflects distinct water/rock or water/water interactions. Therefore, it is assumed that the hydrogeological origin of groundwater at (*) and (**) are different. This indicates that the flow path of groundwater over impermeable ground layers is not simple. 90Sr contamination was not confirmed in both cases, and the 90Sr levels were below the detection limit.

Since the end of 2013, tritium originating from the FDNPP has been detected from the south side of the site. This is the first report of continuous tritium detection on the land side of the site. There are 2 possible causes of elevated tritium on the land side of the site: the leakage of contaminated water from the tanks in 2013 and 2014, or the leakage of tritium from the initial accident, which had already spread widely underground at the FDNPP site. The leaking tritium concentration in water was approximately 20 Bq/L, which is lower than the tritium concentration detected at the nuclear site. In addition, 87Sr/86Sr isotope ratio analysis revealed that groundwater flowing over the impervious layer south of the plant had a different hydrogeological pathway. It appears that an underground route for contaminated water has been established which could lead to future problems. It is necessary to strengthen surveillance of leakage on both the ocean boundary and also land boundary of FDNPP.

Methods

Sample collection

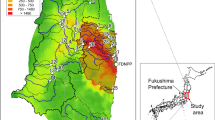

Environmental samples were collected in Okuma Town, Fukushima Prefecture, where the FDNPP is located (Fig. 6). The FDNPP is located adjacent to the north-west Pacific Ocean and is 230 km away from Tokyo. Groundwater samples were collected from 2013 to 2019.

Most of Okuma town is still highly contaminated with radioactive cesium, making it difficult for re-habitation. The reactor buildings (R/B) and turbine buildings (T/B) of the FDNPP face the north-west Pacific Ocean at 10 m or less above sea level, as indicated by blue green in Fig. 3. The contaminated water tanks and treatment facilities are shown in pink on a hill at 35 m above sea level (Fig. 3).

Sampling of the sump water was carried out under a cliff at the boundary of the FDNPP at 17 m above sea level. As shown in the photo in Fig. 3, the sump sample was taken directly from a pipe that was stuck into a cliff. Since the pipe was stuck in the cliff wall, it was possible to directly sample the groundwater. Groundwater could be sampled directly from sump without touching contaminated soil or plants, and was the best place to assess groundwater contamination.

Tritium analysis

3H in water was measured by noble gas mass spectroscopy and a liquid scintillation counter. The suspended matter of the environmental water was removed by filtration (Advantec 5C), and 3H was extracted according to the official MEXT method30. Approximately 50 mg of KMnO4 and 50 mg of Na2O were added to 50 ml of filtered water and distilled for 1 day.

A liquid scintillation counter (LSC) was used for counting the 3H beta emissions (Perkin Elmer Tri-carb 3180 TR). The detection efficiency was determined based on a self-absorption curve with quench correction. The external standard source method using 133Ba was applied to the beta count. A 20 mL low potassium LSC vial was used, and 10 mL of the water sample and 10 mL of a cocktail agent (UltimaGold LLT, Perkin Elmer) were added to each vial and stirred well. Beta emissions were measured at least 2 h after stirring to eliminate auto-fluorescence. For almost all samples, amount of quenching i.e. transformed Spectral Index of External Standard (tSIE), was approximately 300–400, with a detection efficiency of approximately 23%.

The measurement time per vial was 1 day, (1-h cycles, 24 times). The 3H detection limit was approximately 1.5 Bq/L.

Several samples were measured by noble gas mass spectrometry using the In-growth method to check the 3H LSC measurements3,31. In the helium-3 ingrowth method, tritium concentrations were measured in the collected samples at AORI, the University of Tokyo, Japan. After filtration, and distillation of the groundwater samples, they were placed into stainless steel bottles. All dissolved gases, including helium, were extracted from the groundwater by pumping and shaking the samples in an ultrasonic bath. The completely degassed water samples were sealed in the containers. Several months later, 3He produced by 3H decay was analyzed using a conventional noble-gas mass spectrometer at AORI (Helix-SFT; GV Instruments Ltd.). Tritium concentrations were measured indirectly from the measured 3He amounts. The detection limit and the analytical uncertainties of the 3H measurements were estimated to be approximately 0.003 Bq/L and 10%, respectively. Radioactive decay was corrected for as of the sampling date. Comparison of the ingrowth analytical method with the LSC showed good agreement in measured radioactivity.

87Sr/86Sr and 90Sr/86Sr isotope analysis

Water collected at two locations (“*” and “**” in Fig. 6) was used for stable Sr isotope ratio (87Sr/86Sr) analysis and 90Sr (T1/2 = 28.8y) analysis to determine the origin of the spring water and possible 90Sr contamination.

For this purpose, a Phoenix X62 (Isotopx, UK) thermal ionization mass spectrometry (TIMS) was used. For stable strontium concentration measurement, an Agilent-8800 inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, USA) was utilized. The detailed strontium analysis method is described elsewhere32.

The TIMS is equipped with nine Faraday cups (max 10 V), Daly ion counting system (Photomultiplier PM) (50 mV = 3 × 106 CPS), Secondary electron multiplier (SEM), Rear axial Faraday and four Dynode channel electron multipliers known as Channeltron multiple ion counting system. The collector system also comprises a wide aperture retarding potential (WARP) filter to improve abundance sensitivity and transmission efficiency.

For stable strontium isotopes analysis, multi-dynamic while for 90Sr analysis static procedure were applied. 87Sr/86Sr isotope ratio was measured first and next the 90Sr/86Sr isotopic ratio.

A 50 mL water sample was evaporated and dissolved with 5 mL 8 M HNO3. The HNO3 solution was prepared using analytical grade Tamapure AA-100 reagents (68% w/w) and Milli-Q2 purified water (> 18 MΩ cm at 25 °C).

For strontium separation 0.5 mL DGA and Sr extraction chromatography resin of 100–150 µm particle size (Eichrom Technologies Inc, USA) was packed into polypropylene gravity columns (Muromac, Japan; size, 42 mm in length and 5 mm in diameter) and rinsed with 10 mL H2O and preconditioned with 5 mL 8 M HNO3 with a flow rate of ~ 0.2 mL min−1. The sample was dissolved in 5 mL 8 M HNO3, loaded into the prepared columns and rinsed with 3 mL 8 M HNO3 and 3 mL 3 M HNO3. Finally, the Sr was stripped from Sr resin with 3 mL 0.05 M HNO3. This final solution was evaporated to about 0.1 mL and mixed with 0.5 ml HNO3 and 0.5 mL H2O2. The solution was boiled for 10 min and evaporated to dryness. Thereafter, the residue containing Sr was dissolved in 0.25 mL 1 M HNO3 and evaporated to a tiny drop. This tiny drop containing the Sr was loaded onto a degassed single rhenium filament (99.999%) along with one microliter TaF5 activator. More detail of the TIMS analysis is presented elsewhere33.

References

Steinhauser, G. Fukushima’s forgotten radionuclides: A review of the understudied radioactive emissions. Environ. Sci. Technol. 48, 4649–4663 (2014).

Matsumoto, T. et al. Tritium in Japanese precipitation following the March 2011 Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Plant accident. Sci. Total Environ. 445–446, 365–370 (2013).

Takahata, N., Tomonaga, Y., Kumamoto, Y., Yamada, M. & Sano, Y. Direct tritium emissions to the ocean from the Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear accident. Geochem. J. 52, 211–217 (2018).

Tokyo Electric Power Plant Company Holdings (TEPCO). Status of Contaminated Water Status of Contaminated Water Treatment and Tritium at Fukushima Treatment and Tritium at Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station, https://www.meti.go.jp/earthquake/nuclear/pdf/140424/140424_02_008.pdf (2014). Accessed 23 Apr 2020.

Hou, X. Rapid analysis of 14C and 3H in graphite and concrete for decommissioning of nuclear reactor. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 62, 871–882 (2005).

Povinec, P. P. et al. Cesium, iodine and tritium in NW Pacific waters–a comparison of the Fukushima impact with global fallout. Biogeosciences 10, 5481–5496 (2013).

Nuclear Energy Agency, JEFF-3.1.1 Nuclear data libraly

Schwantes, J. M., Orton, C. R. & Clark, R. A. Analysis of a nuclear accident: Fission and activation product releases from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear facility as remote indicators of source identification, extent of release, and state of damaged spent nuclear fuel. Env. Sci. Technol. 46, 8621–8627 (2012).

Tritiated Water Task Force. Tritiated Water Task Force Report. https://www.meti.go.jp/english/earthquake/nuclear/decommissioning/pdf/20160915_01a.pdf (2016). Accessed 23 Apr 2020.

Tritiated Water Task Force. Tritiated Water Task Force Report-Reference materials. (2016) (in Japanese).

Kaizer, J. et al. Tritium and radiocarbon in the western North Pacific waters: Post-Fukushima situation. J. Environ. Radioactiv. 184–185, 83–94 (2018).

Querfeld, R. et al. Radionuclides in surface waters around the damaged Fukushima Daiichi NPP one month after the accident: Evidence of significant tritium release into the environment. Sci. Total Environ. 689, 451–456 (2019).

Kashiwaya, K. et al. Spatial variations of tritium concentrations in groundwater collected in the southern coastal region of Fukushima, Japan, after the nuclear accident. Sci. Rep. 7, 12578 (2017).

Yabusaki, S., Tsujimura, M. & Tase, N. Recent Trend of Tritium Concentration in Precipitation in Kanto Plane, Japan. Bull. Terrest. Environ. Res Center Univ. Tsukuba 4, 119–124. https://doi.org/10.15068/00146987 (2003).

Gosselin, D. C., Edwin Harvey, F., Frost, C., Stotler, R. & Allen Macfarlane, P. Strontium isotope geochemistry of groundwater in the central part of the Dakota (Great Plains) aquifer USA. Appl. Geochem. 19, 359–377 (2004).

Lee, S.-G. et al. Geochemical implication of 87Sr/86Sr ratio of high-temperature deep groundwater in a fractured granite aquifer. Geochem. J. 42, 429–441 (2008).

Nakano, T. Potential uses of stable isotope ratios of Sr, Nd, and Pb in geological materials for environmental studies. Proc. Jpn. Acad. Ser. B Phys. Biol. Sci. 92, 167–184 (2016).

Chakrabarti, R., Mondal, S., Acharya, S. S., Lekha, J. S. & Sengupta, D. Submarine groundwater discharge derived strontium from the Bengal Basin traced in Bay of Bengal water samples. Sci. Rep. 8, 4383 (2018).

Tokyo Electric Power Plant Company Holdings (TEPCO). Water Quality Monitoring of Underground Bypass, https://www4.tepco.co.jp/en/nu/fukushima-np/handouts/2014/images/handouts_140521_05-e.pdf (2014). Accessed 18 Aug 2019.

Tokyo Electric Power Plant Company Holdings (TEPCO). Groundwater Bypass Plan, https://www4.tepco.co.jp/en/nu/fukushima-np/info/13052901-e.html (2013). Accessed 18 Sept 2019.

Tokyo Electric Power Plant Company Holdings (TEPCO). Result of Radioactive Nuclide Analysis around Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station/Archives, https://www4.tepco.co.jp/en/nu/fukushima-np/f1/smp/indexold-e.html. Accessed 23 Apr 2020.

Tokyo Electric Power Plant Company Holdings (TEPCO). Analysis on geology, groundwater flow and radionuclides at Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station and required technology, https://irid.or.jp/cw/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/ws1002_ta_6-2_en.pdf (2013). Accessed 18 Sept 2019.

Tokyo Electric Power Plant Company Holdings (TEPCO). Results of Radioactive Analysis around Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station, https://www4.tepco.co.jp/en/nu/fukushima-np/f1/smp/index-e.html#anchor93 (2020). Accessed 28 Sept 2020.

Shozugawa, K. & Hori, M. Variation of the Radioactivities of 134Cs and 137Cs in flowing-well water and sump water, Okuma Town after the Fukushima nuclear accident. J. Hot Spring Sci. 66, 179–187 (2016).

Tokyo Electric Power Plant Company Holdings (TEPCO). Major Initiatives for Water Management, https://www4.tepco.co.jp/en/decommision/planaction/waterprocessing-e.html. Accessed 23 Apr 2020.

Japan Nuclear Energy Safety Organization. Operational Status of Nuclear Facilities in Japan. 2013Edition (2013).

Tokyo Electric Power Plant Company Holdings (TEPCO). Water Leak at a Tank in the H4 Area in Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station (Follow-up Information), https://www7.tepco.co.jp/wp-content/uploads/hd03-02-04-001-001-07-handouts_130820_03-e.pdf (2013). Accessed 18 Sept 2019.

Tokyo Electric Power Plant Company Holdings (TEPCO). Water Overflow from the flange of the top panel on the upper part of H6 tank area, https://www7.tepco.co.jp/wp-content/uploads/hd03-02-04-001-001-06-handouts_140220_05-e.pdf (2014). Accessed 18 Sept 2019.

McArthur, J. M., Howarth, R. J. & Bailey, T. R. Strontium isotope stratigraphy: LOWESS version 3: Best fit to the marine Sr-isotope curve for 0–509 Ma and accompanying look-up table for deriving numerical age. J. Geol. 109, 155–170. https://doi.org/10.1086/319243 (2001).

Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT), Japan. Analytical methods for tritiumin in Series of Radioactivity measurement (ed MEXT) (2002) (in Japanese).

Palcsu, L., Major, Z., Köllő, Z. & Papp, L. Using an ultrapure 4He spike in tritium measurements of environmental water samples by the . Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 24, 698–704 (2010).

Kavasi, N. et al. Measurement of 90Sr in soil samples affected by the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant accident. J. Radioanal. Nucl. Chem. 303, 2565–2570 (2015).

Kavasi, N., Sahoo, S. K., Arae, H., Aono, T. & Palacz, Z. Accurate and precise determination of 90Sr at femtogram level in IAEA proficiency test using thermal ionization mass spectrometry. Sci. Rep. 9, 16532 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by heartfelt fund, Otsuka corporation, and partly supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 19K12306.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.S. and M.H. collected all environmental samples and data from TEPCO, analyzed tritium by LSC, wrote the manuscript. T.J. and M.M. conceived the ideas of the pathways of underground water. N.T. and Y.S. performed the measurement of tritium by novel gas mass spectrometry. N.K. and S.K.S. performed the analysis of strontium isotope ratio in water samples.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shozugawa, K., Hori, M., Johnson, T.E. et al. Landside tritium leakage over through years from Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear plant and relationship between countermeasures and contaminated water. Sci Rep 10, 19925 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-76964-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-76964-9

This article is cited by

-

Temporal variation of tritium concentration in monthly precipitation collected at a Difficult-to-Return Zone in Namie Town, Fukushima Prefecture, Japan

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2024)

-

Levels and behavior of environmental tritium in East Asia

Nuclear Science and Techniques (2022)

-

Decontamination of Uranium-Contaminated Soil by Acid Washing with Uranium Recovery

Water, Air, & Soil Pollution (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.