Abstract

We report a novel self-patterning method for solution-processed indium zinc oxide (IZO) thin films based on photosensitive precursors. This approach is an alternative and evolutionary approach to the traditional photoresist patterning techniques. Chelate bonds between metal ions and β-diketone compounds in ultraviolet light-exposed IZO solutions provided intrinsic photosensitivity, which resulted in a solubility difference between exposed and non-exposed regions. This difference enabled self-patterning of the IZO for thin-film transistor (TFT) fabrication. Compared with previously reported self-patterning methods based on photosensitive activators, our self-patterned IZO TFTs based on photosensitive precursors displayed excellent electrical characteristics and stability. The field-effect mobility increased from 0.27 to 0.99 cm2/Vs, the subthreshold swing decreased from 0.54 to 0.46 V/dec, and the threshold voltage shift under a positive bias stress test (1,000 s) improved from 9.32 to 1.68 V. The photosensitive precursor played a key role in these improvements permitting fewer organic species which act as defect sites after metal oxide formation. Consequently, our approach compares favorably with that of conventional fabrication process using photoresist in terms of its simplicity, cost efficiency, and electrical performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Solution-processed electronic devices are of increasing interest due to their potential lower cost and vacuum-free fabrication processes. Unlike traditional semiconductor processing, low-temperature solution processes enable the deposition of metal oxides on a broader range of substrate materials (e.g., polyimide) and provide opportunities to produce flexible devices1,2,3. Since the first report of InGaZnO-based thin-film transistors (TFTs), solution-processed amorphous metal oxides have been regarded as some of the most promising materials for next-generation displays because of their high mobility and transparency4,5,6.

Meeting the needs of the times, numbers of solution-based processes have been developed, however, there remain barriers to commercialization, such as the patterning method7. Most applications require metal oxides to be finely patterned to form specific active areas in devices such as TFTs, solar cells, and analog circuits8,9,10,11.

Conventional photolithography process comprises many complex steps, including photoresist coating, vacuum drying, development, etching, and strip. This complexity limits not only the design of circuits, such as the pattern density, pattern profile, and width, but also the characteristics of processes, such as the thickness and profile of the photoresist, and chemical or physical damage to the etching12. Therefore, various alternative patterning methods have been developed such as micro-stamping and ink-jet printing13,14,15. Among them, a self-patternable solution process is of considerable interest because of its simplicity and low cost which means no specialized equipment is necessary. For instance, self-patterning of metal oxide using selective surface wetting has been reported. However additional layer was needed for surface modification; thus, plasma treatment was required to subsequently remove this layer16.

In previous study, we have suggested photoresist-free solution-processed amorphous oxide semiconductor TFTs using photosensitive sol-gels and determined the mechanism of the self-patterning process17. Photosensitive activators based on β-diketone compounds, such as benzoylacetone or acetylacetone (AcAc), play an important role in the presented self-patterning method. The addition of photosensitive activators to metal salts results in the formation of chelate bonds that lead to the crosslinking under ultraviolet (UV) light exposure allowing self-patterning of the metal-oxide film free of the photolithography process.

These results indicate the potential of the self-patterning method. However, some issues remain to be resolved, such as the reducing organic residues. Unwanted organic species from photosensitive activators and metal precursor ligands (e.g., nitrate (NO3–), chloride (Cl–), or acetate (CH3COO–)) remain after film formation; these species can cause degradation of TFT electrical characteristics and reliability18.

Herein, we report a new self-patterning method for solution-processed In–Zn–O (IZO) TFTs that focuses on the reduction of organic residues in the film. This was achieved using photosensitive precursors, rather than photosensitive activators19. The chemical and structural compositions of the self-patterned IZO thin films, based on the AcAc precursor and AcAc activators, were analyzed under the same conditions for comparison. Self-patterned IZO TFTs based on a precursor were named intrinsic photosensitive (IP) IZO TFTs, while self-patterned IZO TFTs based on an activator were named extrinsic photosensitive (EP) IZO TFTs. We confirmed enhancement of the electrical characteristics and stability of the IP IZO TFTs. The ease of processing, as well as the improved electrical characteristics and reliability of the TFTs, are expected to facilitate commercial realization of the self-patterning method.

Experimental Section

Preparation of the IZO solutions

For solution-processed oxide thin-film, synthesis of solution should be undertaken first. Indium acetylacetonate (In(OCCH3CHOCCH3)3) and zinc acetylacetonate hydrate (Zn(C5H7O2)2·xH2O) were selected as precursors to prepare the IP IZO solutions (0.3 M). The precursors were dissolved in 2-methoxyethanol (2ME) at various In:Zn molar ratio (i.e., 1:4, 1:3, 1:2, 1:1, and 2:1) to compare the patternability and electrical characteristics of the IP IZO thin films. An EP IZO solution (0.3 M) was prepared as follows. Indium nitrate hydrate (In(NO3)3·xH2O) and zinc nitrate hydrate (Zn(NO3)2·xH2O) were dissolved in 2ME at the In:Zn molar ratio of 1:2, which was the optimal ratio in terms of TFT electrical characteristics. This is the preparation method for conventional IZO solutions. Then, AcAc was added as photosensitizer. The mixture was stirred for 1 h at 70 °C and aged another 24 h at room temperature.

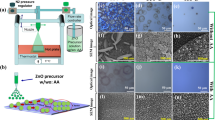

Fabrication of IZO TFTs using the self-patterning method

The IP and EP IZO TFTs were fabricated under exactly the same conditions for comparison (Fig. 1). The device substrate was a heavily-doped p-type Si wafer on which a 1,200-Å-thick SiO2 layer had been thermally grown. After a standard cleaning procedure, the EP or IP IZO solution was spin-coated onto the substrate at 3,000 rpm for 30 s, then pre-annealed at 90 °C for 10 min. The pre-annealed IZO thin films were subsequently exposed to UV light—main emission peaks were at 253.7, 294.7, 302.2, and 365.0 nm—while a shadow mask was applied to the film for 15 min in ambient air. Following UV irradiation, the non-exposed IZO was etched by immersion in ethanol for 5 s, and post-annealed at 350 °C for 1 h in air. Source and drain electrodes were deposited by Al thermal evaporation; channel length and width are 150 and 1,000 μm, respectively.

Film and device characterization

The optical absorbances of the IZO solutions at various wavelengths were measured using a UV–visible spectrophotometer (model V-650; JASCO). Images of the self-patterned IZO films were acquired using an optical microscope (model BX-51; Olympus). The chemical properties of the IZO thin films were analyzed by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) (model K-alpha; Thermo Fisher Scientific) and Fourier transform-infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) (model Vertex 70; Bruker).

A Hall effect measurement system (model HMS 3000; ISTECH) was used to measure the semiconductor characteristics. The thickness of a patterned film was measured by atomic force microscopy (AFM) (model NX10; Park). The electrical characteristics of an IZO TFT were measured using a semiconductor parameter analyzer (model HP 4156C; Agilent Technologies) in a dark box under ambient conditions. The transfer curve was measured at a fixed drain voltage (VDS) of 10.1 V as the gate voltage (VGS) was swept from –30 to 30 V. A positive bias stress (PBS) test was carried out at a VGS of 20 V and VDS of 10.1 V for 1,000 s.

Discussion

In our previous research involving EP IZOs, metal salts (MXn; n = 4) dissolved in β-diketone compounds formed metal chelate bonds by exchanging the X ligands, such as chloride (Cl–), acetate (CH10COO–), or nitrate (NO3–). UV irradiation induced π → π* electronic transitions and decomposition of these chelate ring structures, which consisted of a central metal ion surrounded by β-diketonato ligands. The partial distribution of excited electrons on the oxygen atoms reduced the coordination strength between the metal ion and the β-diketonato ligands. As a result, this gradual decomposition allowed photosensitive behavior altering its solubility in some organic agent leading to hydrolysis of the IZO thin films20,21. This series of reactions is depicted in Fig. 2a.

On the other hand, in our newly developed method, the IP IZO was made using AcAc-based precursors, which already exhibited chelate bonds between the metal ion and the β-diketonato ligands. In this instance, fewer organic residues originating from the ligands were expected to remain after hydrolysis and crosslinking (Fig. 2b). In both instances, the dissociation of the metal chelate bonds under UV exposure provided photosensitivity. The solubility difference between the UV-exposed and non-exposed regions enabled patterning of the IZO thin film.

Figure 3 compares the optical absorption spectra of three types of IZO solutions: conventional, EP, and IP. The strong absorption bands of the IP and EP solutions between 300 and 350 nm originated from the metal chelate bonds. Regarding the EP IZO solution, the peak at 330 nm was attributed to the formation of metal chelate bonds between In3+ and Zn2+ metal cations and AcAc (In(AcAc)(NO3)2 and Zn(AcAc)NO3)17. A similar absorption peak at 330 nm observed for the IP IZO solution was attributed to the AcAc-based precursor.

On the basis of above photoreactivity, we fabricated the IP IZO TFFs on the Si substrate as shown in Fig. 4a. A finely patterned 35-nm-thick IZO channel was made, which is suitable for TFTs with micron-sized lateral dimensions. Additionally, for practical applications, we demonstrated 3 inch wafer-scale patterned IP IZO films with various sizes and shapes (see Supplementary Fig. S1 online), and it was confirmed that the patterns such as elliptical and rectangular shapes were formed uniformly; the short axis of smallest ellipse is 40 μm and the width of the smallest rectangle is 60 μm. Figure 4b shows the transfer curves of IP IZO TFTs made with various In:Zn molar ratios (i.e., 1:4, 1:3, 1:2, 1:1, and 2:1). We previously established that In was a carrier supplier in the ZnO phase22. Herein, a similar trend was observed: elevated field-effect mobility (μFET) from 0.01 to 1.55 cm2/Vs, reduced in Ion/off ratio from approximately 106 to 102, and increased subthreshold swing (S.S) from 0.93 to 12.49 V/dec with increasing In ratio. Table 1 summarizes the parameter variations. The clear switching behavior in the transfer curve for the In:Zn molar ratio of 1:2 indicated that this was the optimal ratio.

Figure 5a shows the transfer curves of the IZO TFTs with the same molar ratio of 1:2, which were made from but with different types of EP and IP IZO solutions. Regarding the IP IZO, μFET of 0.99 cm2/Vs, Ion/off ratio of 1.00 × 109, and S.S of 0.46 V/dec were observed. Meanwhile, the EP IZO exhibited relatively inferior characteristics with μFET of 0.27 cm2/Vs, Ion/off ratio of 1.07 × 107, and S.S of 0.54 V/dec; the distributions of electrical parameters for the IP and EP IZO TFTs are summarized in Fig. 5b–d and Table 2. When comparing the output characteristics of EP and IP IZO TFTs in Fig. 5e,f, it was confirmed again that the current-level of IP IZO TFT is much higher than that of EP IZO TFT.

A similar trend was observed in the Hall measurement data (Fig. 6a). The IP IZO thin film showed elevated carrier concentration from 3.67 × 1016 to 8.43 × 1016/cm3 and reduced resistivity from 1.24 × 104 to 2.73 × 103 Ωcm, compared with the EP IZO thin film; these characteristics suggested fewer defects in the IP IZO phase. We previously reported that incomplete decomposition and volatilization of β-diketone photosensitive activators during metal oxide formation resulted in organics residues that degraded TFT performance. We presumed that these performance differences were derived from relatively low concentrations of residues in IP IZOs compared with the corresponding EP IZOs after film formation.

FT-IR spectroscopy of the IZO thin films was carried out to support this hypothesis (Fig. 6b). Peaks at 1,116 and 1,265 cm−1 in the EP IZO spectrum were assigned to nitrogen-related vibrations of molecules (e.g., C–N, N = O, and N–H) or as NO3– deformations, most of which originated from nitrate precursors of EP IZOs23,24,25,26. Additionally, broad peaks in the range from 2,000 to 2,700 cm−1 indicated the presence of C=O, O–H, and C–H groups, which derived from incomplete formation of metal chelate bonds between metal ligands and AcAc27,28. These results confirmed the presence of considerable amounts of organic residues from the metal precursors and photosensitive activator that formed during film formation29. On the other hand, most peaks in the range from 1,000 to 1,500 cm−1 were absent in the spectrum of IP IZO. In the range from 2,000 to 2,700 cm−1, some residues from acetylacetonate metal precursors still remained, and relatively small absorbance peaks were shown as already predicted. These findings indicate that uniformly formed metal chelate bonds in acetylacetonate metal precursors are important for the quality of thin films.

Additionally, the chemical and structural compositions of the EP and IP IZO films were analyzed by XPS measurements. Figure 7a,b show the In 3d5/2 and Zn 2p3/2 peaks for the In–O and Zn–O bonds, respectively. For the IP IZO thin film, a shift toward higher binding energy from 444.88 to 444.98 eV and broadening of In 3d5/2 were observed which slightly broadened the peak compared with those of the EP IZO thin film. It has been reported that oxidized states of In-O compounds have higher binding energy and broader peak than In30,31. In this respect, the In 3d5/2 peak represent that more oxidation and better activation was occurred during IP IZO film formation. Same tendency was also shown in Zn 2p3/2 peak, slight shift to a higher binding energy, compared with those of the EP IZO thin film; this observation was consistent with the stronger tendency of the IP IZO thin film to undergo oxide formation32,33. Figure 7c,d show the O 1 s peak deconvoluted into three peaks centered at 530, 531, and 532 eV34.

The OI peak at 530 eV, derived from the oxide lattice in the metal oxide phase, represents advanced conducting pathways for electrons in IP IZO (EP: 56.68%, IP: 62.23%). Meanwhile, the OII peak at 531 eV is associated with oxygen vacancies (VOs), and the OIII peak at 532 eV is attributed to metal–hydroxide (M–OH) or metal–oxycarbon (M–OC) groups of organic residues35. The reduction in the intensity of these two peaks (i.e., OII from 25.98% to 23.67%; OIII from 17.34% to 14.10%) indicated an overall reduction of oxygen impurities that generate trap sites and deteriorate performance. It has been reported that carbon-related species in IZO tend to strongly attract oxygen compared with In or Zn, and interfere with metal oxide (M–O) bond formation36. These reactions result in the formation of VOs (as evidenced by the OII peak) and defect states. In this term, the smaller OII peak for IP IZO indicated fewer defect states and better M–O bonding.

In the IP IZO solution, the only sources of carbon and oxygen impurities were the 2ME solvent and AcAc-based metal precursors. However, in the EP IZO solution, the AcAc activator was an additional impurity source in addition to the 2ME solvent and metal nitrate precursors. Consequently, these results figure out that the IP IZO thin film had enriched M–O bonding and contained fewer organic residues such as carbon or hydroxyl groups compared with the EP IZO thin film. The effect of these impurities was more discernable under bias stress test. Figure 8a,b shows the results of PBS test of the EP and IP IZO TFTs. The bias test was carried out at VGS = 20 V and VDS = 10.1 V for 1,000 s in the dark. As a natural consequence, the IP IZO TFT showed enhanced stability with a threshold voltage shift (ΔVth) of 1.68 V, compared with 9.32 V for the EP IZO TFT.

Conclusion

In summary, we have demonstrated a novel self-patterning method for low-temperature solution-processed IZO TFTs. The AcAc based precursors provided intrinsic photosensitivity to the IZO solution, which self-patterned under UV irradiation. Compared with the conventional self-patterning method using photosensitive activators, our method provided higher-quality IZO thin films with fewer organic residues by limiting the possible sources of organic species to the 2ME solvent and the AcAc based precursors. By arranging M–O bonding of IZO uniformly with decreased VOs, a significant increase in the electrical characteristics in the transfer curve was achieved: μFET increased from 0.27 to 0.99 cm2/Vs, and S.S decreased from 0.54 to 0.46 V/dec. Furthermore, the ΔVth under PBS tests improved from 9.32 to 1.68 V. Consequently, our new self-patterning method of IZO thin films is a commercially viable technique that reduces manufacturing cost and process steps due to non-necessity of photoresist but also contribute to superior electrical characteristics without degradation caused by organic residues.

References

Fortunato, E., Barquinha, P. & Martins, R. Oxide semiconductor thin-film transistors: a review of recent advances. Adv. Mater. 24, 2945–2986 (2012).

Park, S. P., Kim, H. J., Lee, J. H. & Kim, H. J. Glucose-based resistive random access memory for transient electronics. J. Inf. Disp. 20, 231–237 (2019).

Wang, Z. et al. Cluster size control toward high performance solution processed InGaZnO thin film transistor. ACS. Appl. Electron. Mater. 1, 2483–2488 (2019).

Li, Y. et al. High-performance thin-film transistors with aqueous solution-processed NiInO channel layer. ACS. Appl. Electron. Mater. 1, 1842–1851 (2019).

Kim, M. G., Kanatzidis, M. G., Facchetti, A. & Marks, T. J. Low-temperature fabrication of high-performance metal oxide thin-film electronics via combustion processing. Nat. Mater. 10, 382–388 (2011).

Lee, I. S. et al. Improving the performances of oxide phototransistors using a mechanochemically treated porous visible-light absorption layer. J. Inf. Disp. https://doi.org/10.1080/15980316.2019.1708820 (2019).

Park, J. W., Kang, B. H. & Kim, H. J. A review of low-temperature solution-processed metal oxide thin-film transistors for flexible electronics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 1904632 (2020).

Lin, H. C. et al. Deep ultraviolet laser direct write for patterning sol-gel InGaZnO semiconducting micro/nanowires and improving field-effect mobility. Sci. Rep. 5, 10490 (2015).

Rim, Y. S. et al. Direct light pattern integration of low-temperature solution-processed all-oxide flexible electronics. ACS Nano 8, 9680–9686 (2014).

Aumaitre, C., Joly, D., Aldakov, D. & Demadrille, R. Syntax of referencing in The Future of Semiconductor Oxides in Next-Generation Solar Cells (ed. Lira-Cantu, M.) 85–115 (Elsevier, 2018).

Pecunia, V., Fattori, M., Abdinia, S., Sirringhaus, H. & Cantatore, E. Organic and amorphous-metal-oxide flexible analogue electronics (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2018).

Chen, C. Y. et al. Plasma damage-enhanced negative bias temperature instability in low-temperature polycrystalline silicon thin-film transistors. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 27, 893–895 (2006).

Liang, K. et al. High-performance metal-oxide thin-film transistors based on inkjet-printed self-confined bilayer heterojunction channels. J. Mater. Chem. C. 7, 6169–6177 (2019).

Wei, X. et al. Solution-processed flexible metal-oxide thin-film transistors operating beyond 20 MHz. Flex. Print. Electron. 5, 015003 (2020).

Sanjana, N. E. & Fuller, S. B. A fast flexible ink-jet printing method for patterning dissociated neurons in culture. J. Neurosci. Methods 136, 151–163 (2004).

Lee, W. J. et al. Large-scale precise printing of ultrathin sol-gel oxide dielectrics for directly patterned solution-processed metal oxide transistor arrays. Adv. Mater. 27, 5043–5048 (2015).

Rim, Y. S., Lim, H. S. & Kim, H. J. Low-temperature metal-oxide thin-film transistors formed by directly photopatternable and combustible solution synthesis. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 5, 3565–3571 (2013).

Li, Y., Zhao, G. Y., Zhang, W. H. & Chen, Y. Q. Using the photolysis of chemically modified gel films preparing ITO fine patterned thin films. J. Disp. Technol. 2, 175–179 (2006).

Kim, H. J. et al. Self-pattern process of InZnO thin-film transistors using photosensitive precursors. SID Int. Symp. Dig. Tech. Pap. 48, 180–182 (2017).

Chen, Y., Zhao, G., Ren, Y. & Wang, Z. Microfabrication of dilute magnetic semiconducting Ti1-xCoxO2 films using photosensitive sol-gel method. Thin Solid Films 519, 1985–1988 (2011).

Chen, Y. Q., Zhao, G. Y. & Yan, F. X. Ferromagnetic Co-doped ZnO film and fine patterns prepared using photosensitive sol-gel method. J. Sol-Gel Sci. Technol. 54, 325–328 (2010).

Koo, C. Y. et al. Low temperature solution-processed InZnO thin-film transistors. J. Electrochem. Soc. 157, J111–J115 (2010).

Ahn, B. D., Jeon, H. J. & Park, J. S. Effects of Ga: N addition on the electrical performance of zinc tin oxide thin film transistor by solution-processing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 6, 9228–9235 (2014).

Park, J. H. et al. Boron-doped peroxo-zirconium oxide dielectric for high-performance, low-temperature, solution-processed indium oxide thin-film transistor. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 5, 8067–8075 (2013).

Pham, H. T. & Jeong, H. D. Newly observed temperature and surface ligand dependence of electron mobility in indium oxide nanocrystals solids. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 7, 11660–11667 (2015).

John, R. A. et al. Low-temperature chemical transformations for high-performance solution-processed oxide transistors. Chem. Mater. 28, 8305–8313 (2016).

Kowalewska, A., Nowacka, M., Tracz, A. & Makowski, T. Supramolecular self-assembly of linear oligosilsesquioxanes on mica-AFM surface imaging and hydrophilicity studies. Soft Matter 11, 4818–4829 (2015).

Yeh, C. C. et al. Controllable formation of zinc oxide micro- and nanostructures via DUV direct patterning. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 3, 1600373 (2016).

Jung, J. et al. Approaches to label-free flexible DNA biosensors using low-temperature solution-processed InZnO thin-film transistors. Biosens. Bioelectron. 55, 99–105 (2014).

Nomura, K. et al. Amorphous oxide semiconductors for high-performance flexible thin-film transistors. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 45, 4303–4308 (2006).

Hewitt, R. W. & Winograd, N. Oxidation of polycrystalline indium studied by x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy and static secondary ion mass spectroscopy. J. Appl. Phys. 51, 2620–2624 (1980).

Lan, L. F. et al. Enhancement of bias and illumination stability in thin-film transistors by doping InZnO with wide-band-gap Ta2O5. Appl. Phys. Lett. 102, 242102 (2013).

Zan, H. W. et al. Achieving high field-effect mobility in amorphous indium-gallium-zinc oxide by capping a strong reduction layer. Adv. Mater. 24, 3509–3514 (2012).

Seo, S. J., Hwang, Y. H. & Bae, B. S. Postannealing process for low temperature processed sol-gel zinc tin oxide thin film transistors. Electrochem. Solid-State Lett. 13, H357–H359 (2010).

Rim, Y. S., Ahn, B. D., Park, J. S. & Kim, H. J. Manifestation of reversal conductivity on high pressurizing of solution-processed ZnSnO thin-film transistors at low temperature. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 47, 045502 (2010).

Di Valentin, C., Pacchioni, G. & Selloni, A. Theory of carbon doping of titanium dioxide. Chem. Mater. 17, 6656–6665 (2005).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Nano Material Technology Development Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by Ministry of Science and ICT under Grant 2018M3A7B4071521.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.J.Kim (first author) organized the data and drew figures. J.Jung wrote the main manuscript text. All authors reviewed the results and implications and commented on the manuscript at all stages. The project was guided by H.J.Kim (corresponding author).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, H.J., Jung, J. & Kim, H.J. Enhancement of electrical characteristics and stability of self-patterned In–Zn–O thin-film transistors based on photosensitive precursors. Sci Rep 10, 18853 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-76080-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-76080-8

This article is cited by

-

Influence on Post-treatment Process on Optical and Electrical Properties of IZO Thin Films

Transactions on Electrical and Electronic Materials (2024)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.