Abstract

Birth by cesarean section is increasing worldwide and associates with offspring morbidities capable of adversely impacting cardiorespiratory fitness later in life. Whether birth by cesarean section associates with lower levels of cardiorespiratory fitness later in life is unknown and is of interest to public health. Four Swedish national registers were linked to follow 339,451 singleton males, born between 1973–1987 until December 31 2005, for Watt-maximum achieved on a cycle ergometer test at conscription into the Swedish military. Main exposure was birth by cesarean section which was compared to vaginal birth. A sub-population of 45,999 males born between 1982–1987 was identified to explore differentiated associations between elective and non-elective cesarean section with Watt-maximum. Within-family analyses of 34,252 families with 70,632 biological male siblings, who conscripted during the study period, were performed to explore the role of familial confounding on Watt-maximum. Swedish males born by cesarean section achieved lower mean Watt-maximum (− 2.32 W, 95%C.I. − 2.90 to − 1.75) and displayed excess odds of low cardiorespiratory fitness (aOR = 1.08, 95%C.I. 1.05 to 1.11) at conscription in the eighteenth life-year compared to males born vaginally after adjusting for birth characteristics, maternal morbidities and parental socioeconomic position. In the sub-population, males born 1982–1987, there was a greater negative association of elective cesarean section with cardiorespiratory fitness (− 4.42 W, 95%C.I. − 6.27 to − 2.57, p < 0.001) than non-elective cesarean sections (− 1.96 W, 95%C.I. − 3.77 to − 0.16, p = 0.033) as compared to vaginal births. No associations between modes of cesarean delivery and cardiorespiratory fitness levels persisted in the within-family analyses where biological male siblings were compared whilst controlling for factors shared within families. Males born by cesarean section had lower levels of cardiorespiratory fitness eighteen years later compared to males born vaginally. These findings appear to be largely explained by factors of familial confounding.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The incidence of cesarean section (CS) is increasing worldwide and the global prevalence nearly doubled from 12.1% of all births in 2000 to 21.1% in 20151,2,3,4,5. Maternal and offspring health outcomes associated with CS are consequently of growing interest for public health but are not fully understood. CS rates between 10 and 15% at the population level have been suggested as motivated from a medical viewpoint on the basis that no reductions in maternal or fetal mortality can be found above these rates6,7,8. On the one hand, CS is a vital-indication intervention that reduces maternal and fetal mortality and morbidity. On the other, maternal medical histories of CS are associated with persistent severe obstetric risks in later pregnancies as well as with an excess maternal morbidity burden9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17. Epidemiological studies have shown associations between birth by CS with excess risks of a range of offspring morbidities each capable of adversely impacting cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) later in life10,18,19,20,21,22,23. If CS is a causal factor in such morbidities, it is possible that CS would impact CRF. CRF is a gender-independent predictor of mortality, morbidity and long-term survival24,25,26. Levels of CRF are inversely associated with risks of all-cause mortality, premature death, death from cardiovascular disease and cancer independent of traditional risk factors such as obesity, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia and socioeconomic position27,28,29,30,31,32,33.The high prognostic value of CRF on long-term survival and disease-specific morbidities throughout an individual’s lifetime underscores the importance to public health of understanding drivers of CRF and targeting early-life interventions to improve CRF. We posited three specific research questions; (i) whether birth by CS in Swedish males born 1973–1987 are associated with lower levels of CRF later in life; (ii) whether such an association differs between elective and non-elective CS in a sub-population of males born 1982–1987 and (iii) whether any associations found robustly persist across within-family analyses.

Materials and methods

Study design

We conducted a population-based longitudinal cohort study using nationwide register-linked data on Swedish males born between 1973–1987. The analytic sample was followed until December 31, 2005 for Watt-maximum (Wmax) achieved on a cycle ergometer test during standardized nationwide conscription into the Swedish military. To explore associations of modes of cesarean delivery with Wmax we identified a sub-population of males born between 1982–1987 for which register data allowed differentiation between elective and non-elective CS. To investigate the impact of familial confounding on Wmax we identified biological brothers in the analytic sample and performed within-family sibling comparison analyses.

Data sources

The unique Swedish personal identity number was used to link four Swedish nationwide registers34. The Swedish Medical Birth Register (MBR), containing compulsory reported data from all birth clinics on nearly all deliveries in Sweden since 1973, was used to collect data on modes of delivery, birth characteristics and maternal medical histories35. The Swedish Military Service Conscription Register was used to collect CRF data at conscription into the Swedish military. The Population and Housing Censuses (PHC) were used to collect information on parental education levels, household disposable income, parental country of birth and parental socioeconomic position. The Swedish Multigeneration Register facilitated linking of individual family members into family clusters permitting within-family analyses of biological male siblings.

Study population

A flow diagram detailing the construction of the analytic sample, family clusters and analytic sub-population and are shown in Fig. 1. The study population of all Swedish singleton males born between 1973–1987 (N = 762,262) was identified from the MBR. Individuals where data was missing on delivery mode (N = 22,877, 3.0%), birth weight and/or gestational age (N = 6849, 0.9%), maternal age (N = 45, < 0.1%) and parental socioeconomic variables (N = 20,488, 2.7%) were excluded. Further, individuals who did not conscript into Swedish military service during the study period (N = 98,514, 12.9%) were excluded. The resulting cohort (N = 613,489, 80.5%) was matched with conscription data as recorded in the Swedish Military Service Conscription Register. Individuals with extreme values of height (below 150 cm or above 210 cm), weight (below 40 kg or above 150 kg) or body-mass index (BMI) (below 15 kg/m2 or above 60 kg/m2) (N = 276, < 0.1%) as well as individuals who conscripted but were not allowed to perform the maximum load cycle ergometer test (N = 273,762, 35.9%) were excluded to define the main analytic sample (N = 339,451). To explore the role of familial confounding on Wmax, we identified 34,252 families with 70,632 biological brothers in the main analytic sample who all conscripted during the study period. To explore the associations of modes of cesarean delivery with Wmax, we defined a sub-population of males born 1982–1987 (N = 45,999) where MBR data allowed differentiation between elective and non-elective CS deliveries, respectively.

Exposure and controls

Exposure in the main analytic sample was defined as births by CS (N = 29,910, 8.8%) and these were compared to vaginal births (N = 309,541, 91.2%). In the analytic sub-population of males born 1982–1987, exposures were defined as elective (N = 1903, 4.1%) and non-elective (N = 1958, 4.3%) CS, respectively and compared to vaginal births (N = 42,138, 91.6%). The reporting standards of the MBR remained constant throughout the study period and defined elective CS as CS delivery before the onset of labor, and non-elective CS as CS delivery after the onset of labor.

Outcome

Wmax, a validated proxy measure of CRF36, was defined as outcome. During the study period conscription in Sweden was mandated by law and exemption from conscription required stated medical approval, usually granted to those with severe medical conditions. All recruits called for conscription in the eighteenth life-year, who were considered medically fit, were invited to take the adjustable resistance cycle ergometer test during standardized nationwide conscription. Individuals eligible for conscription but who were not considered medically fit during conscription testing due to muscular och skeletal injuries, abnormal resting ECG or other relevant medical indications were excluded from performing the ergometric testing by supervising physicians. The maximum work output achieved by each recruit at exhaustion, measured in Watts, was recorded as their respective Wmax. We quantified associations between modes of delivery with mean Wmax and with low CRF, where we ordered Wmax into quartiles and categorically defined low CRF as the lowest quartile of recruits (≤ 270 Wmax). Within-family analyses in the linear regression model were performed on 70,632 continuously outcome discordant siblings and on 20,590 categorically outcome discordant siblings in the logistic model.

Other covariates

We used known indications for cesarean delivery and predictors of fetal health and development as covariates in our main analyses. We adjusted for birthweight and gestational age since both are positive predictors of CRF later in life37,38. Maternal covariates at the time of delivery included age39, parity40, diabetes41,42, hypertension43, preeclampsia during pregnancy44,45 and systemic lupus erythematosus46,47. Increased data coverage in the MBR after 1982 allowed additional adjustments in our analyses on the sub-population of males born 1982–1987 of pre-pregnancy BMI40,48 and self-reported smoking habits during pregnancy49,50. From the PHC we acquired data collected from the census conducted closest to the time of delivery on highest parental educational level, household disposable income (in quintiles), parental country of birth (Sweden or one/two parents born outside Sweden) and highest parental occupational class.

Statistical analysis

Linear and logistic regression were employed to estimate mean difference in Wmax and odds ratios (OR) of low CRF in males born 1973–1987 by any CS as compared to males born vaginally. The same methodology was applied to males in the analytic sub-population born 1982–1987, where we differentiate between elective and non-elective CS as compared to males born vaginally. Within-family analyses employed fixed-effects (conditional) linear and logistic regressions, thereby accounting for genetic and environmental familial factors shared between biological brothers. Within-family analyses were adjusted similarly as other analyses, with the exception of parental education and parental country of birth which did not vary between brothers. For all analyses standard errors were estimated using the robust (sandwich) method to account for correlation between biological brothers. Significance tests were two sided and statistical analyses were performed using STATA 15.1 (Stata Corp.)

Sensitivity analysis

To explore possible heterogeneity in vaginal births we differentiated vaginal delivery with forceps and/or vacuum extraction from non-instrumental vaginal delivery, Supplementary Table S2. To verify that individuals excluded because of extreme-value conscription data did not materially impact our findings, we included those previously excluded (Model 1). To relax linearity assumptions of covariates, we employed restricted cubic splines with five knots at percentiles suggested by Harrell51 (5th, 27.5th, 50th, 72.5th and 95th percentiles) for maternal age, household disposable income, gestational age and birthweight standardized according to gestational age (Model 2). To explore the possible influence of both a previous CS and maternal weight gain during pregnancy in the analytic sub-population we adjusted for a maternal medical history of CS after 1972 (Model 3) and standardized maternal gestational weight gain, according to a Swedish reference methodology52 (Model 4). To explore the possibility that gestational age is a collider on causal pathways between CS and Wmax we excluded adjustment for gestational age (Model 5). To ascertain that the effect of CS on Wmax is not limited to the extremes of gestational age we excluded pre-term births (< 37 weeks, Model 6) and restricted the analytic sample to males born at-term (Model 7).

Ethics declaration

The study was approved by the Stockholm ethical review board (Dnr:2016/1445-31/1) and carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was not required for analysis of anonymized register data and formally waived by the approving committee. Additional approval from the National Board of Health and Welfare, the Swedish Military Service Conscription Registry and Statistics Sweden was secured prior to collecting the data. All data was collected in accordance with Swedish data privacy legislation and was anonymized using a conversion key held by Statistics Sweden.

Results

Population characteristics

Vaginally born males achieved higher Wmax (304.0 W) compared to males born by CS (301.0 W) and were of the same median age during conscription testing (18.3 years old), Table 1. Vaginally delivered males had higher average birth weights (3602.2 g) and longer gestational periods (39.7 weeks) compared to males delivered through CS (3398.8 g, 38.8 weeks), Table 1. Mothers who gave birth through CS were older (28.8 years old), more likely to have a university degree (40.0%) and be primiparas (median parity 1.0) and were part of households with higher disposable income (51.1% quintiles 4–5) compared to mothers who delivered vaginally (27.2 years old, 37.6% university degree, median parity 2.0 and 47.8% quintiles 4–5), Table 1.

Population characteristics of the analytic sub-population of males born 1982–87 were similar compared to the main analytic sample, Supplementary Table S1. Mothers who gave birth through non-elective CS had a higher pre-pregnancy BMI (17.7% overweight or obese) and were more likely to smoke during pregnancy (29.9% smokers) compared to mothers who delivered vaginally (12.6% overweight or obese, 25.5% smokers) and mothers who delivered through elective CS (16.6% overweight or obese, 25.9% smokers), respectively, Supplementary Table S1. Mothers who gave birth through elective CS were part of households with higher disposable income (39.7% quintiles 4–5) compared to mothers who delivered vaginally and through non-elective CS (33.2% and 33.9% quintiles 4–5 respectively). Population characteristics of excluded individuals are shown in Supplementary Table S4.

Cesarean delivery and cardiorespiratory fitness

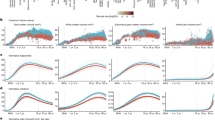

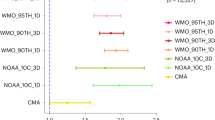

Male offspring born by CS between 1973–1987 achieved lower Wmax (− 2.32 W, 95%C.I. − 2.90 to − 1.75, p < 0.001, Fig. 2) and showed excess odds of low CRF (aOR = 1.08, 95%CI 1.05 to 1.11, p < 0.001, Fig. 3) compared to males born vaginally after adjusting for birth characteristics, maternal morbidities and socioeconomic position. When comparing 70,632 biological siblings across 34,252 families in the main analytic sample, of which 4750 and 1479 siblings were fully exposure and outcome discordant in the linear (Fig. 2) and logistic (Fig. 3) model respectively, the associations of CS with Wmax at conscription attenuated towards the null, with the exception of birth by any CS (elective and non-elective combined) in the within-family linear regression model which showed a statistically significant positive association with Wmax after fully adjusting for covariates (2.79 W, 95%C.I. 0.48 to 5.10, p = 0.018, Fig. 2). Associations with Wmax did not differ between males born by instrumental vaginal birth and those delivered by unassisted vaginal births suggesting no impact on Wmax from heterogeneity in vaginal births, Supplementary Table S2. Associations between birth by CS with lower levels of CRF, as compared to vaginal births, were stable and persisted across all sensitivity analyses performed, Supplementary Table S3.

Association between cesarean section and Wmax performance at conscription in the 18th life-year for the main analytic sample, within-family analyses and analytic sub-population. Superscript 1: Adjusted models in main analyses show linear regression estimates of mean difference in Wmax, as measured in Watts (W), 95% confidence intervals and p-values between individuals born through cesarean section (elective and non-elective combined) as compared to all individuals born vaginally. Adjustments included: birthweights standardized according to gestational age, gestational age, maternal age, parity, maternal diseases (diabetes, hypertension, preeclampsia, SLE), highest parental educational level, household disposable income, parental country of birth and highest parental occupational class. Superscript 2: Within-family analyses were similar in terms of adjustments (excluding parental country of birth and highest parental education) to the main analyses and were performed on all biological siblings in the main analytic sample who conscripted during the study period. Superscript 3: Adjusted models in the analytic sub-population show linear regression estimates of mean difference in Wmax, as measured in Watts (W), 95% confidence intervals and p-values between individuals born through cesarean section (elective and non-elective combined as well as differentiated by mode of cesarean delivery) as compared to all individuals born vaginally. Adjustments included: birthweights standardized according to gestational age, gestational age, maternal age, parity, maternal diseases at time of giving birth (diabetes, hypertension, preeclampsia, SLE) and parental educational level, disposable income, country of birth and occupational class as well as pre-pregnancy BMI and self-reported maternal smoking habits during pregnancy.

Association between cesarean section and low cardiorespiratory fitness at conscription in the 18th life-year for the main analytic sample, within-family analyses and analytic sub-population. Superscript 1: Adjusted models in main analyses show logistic regression estimates of odds ratios of low CRF (defined as lowest quartile of Wmax achieved by all recruits during the study period), 95% confidence intervals and p-values between individuals born through cesarean section (elective and non-elective combined) as compared to all individuals born vaginally. Adjustments included: birthweights standardized according to gestational age, gestational age, maternal age, parity, maternal diseases (diabetes, hypertension, preeclampsia, SLE), highest parental educational level, household disposable income, parental country of birth and highest parental occupational class. Superscript 2: Within-family analyses were similar in terms of adjustments (excluding parental country of birth and highest parental education) to the main analyses and were performed on all biological siblings in the main analytic sample who conscripted during the study period. Superscript 3: Adjusted models in sub-population show logistic regression estimates of odds ratios of low CRF (defined as lowest quartile of Wmax achieved by all recruits during the study period), 95% confidence intervals and p-values between individuals born through cesarean section (elective and non-elective combined as well as differentiated by mode of cesarean delivery) as compared to all individuals born vaginally. Adjustments included: birthweights standardized according to gestational age, gestational age, maternal age, parity, maternal diseases at time of giving birth (diabetes, hypertension, preeclampsia, SLE) and parental educational level, disposable income, country of birth and occupational class as well as pre-pregnancy BMI and self-reported maternal smoking habits during pregnancy.

Modes of cesarean delivery and cardiorespiratory fitness

For males in the analytic sub-population born 1982–1987 associations of birth by any cesarean delivery method with Wmax were similar to the main analytic sample after similar adjustments with the addition of pre-pregnancy BMI and self-reported maternal smoking habits during pregnancy, Fig. 2. When differentiating between modes of cesarean delivery and after adjusting for confounders, both elective and non-elective CS associated with lower mean Wmax at conscription (Mean difference = − 4.42, 95%CI − 6.27 to − 2.57, p < 0.001 and − 1.96, 95%CI − 3.77 to − 0.16, p = 0.033 respectively, Fig. 2) as compared to vaginal delivery. Elective CS in the logistic model associated with increased odds of low CRF at conscription (aOR = 1.15, 95%CI 1.04 to 1.28, p = 0.009, Fig. 3). Non-elective CS associated with increased odds of low CRF at conscription (aOR = 1.10, 95%CI 0.99 to 1.22, Fig. 3) although not statistically different from vaginal deliveries (p = 0.082). There was no difference between elective CS and non-elective CS in their association to mean Wmax (p = 0.055) and odds of low CRF (p = 0.505), as compared to those born by vaginal delivery.

Discussion

Principal findings

Our analysis of data from Swedish nationwide health and administrative registers, of 339,451 singleton males born 1973–1987, suggested that males born by CS have lower levels of CRF in the eighteenth life-year compared to males born vaginally. The association between CS with low CRF persisted across all sensitivity analyses performed. Analysis of data in our sub-population of 45,999 singleton males born 1982–1987, for which modes of cesarean delivery were differentiated, indicated that both elective and non-elective cesarean delivery associated with lower levels of CRF later in life as compared to vaginal delivery, albeit not statistically significant in the case of non-elective CS. When comparing 70,632 biological siblings across 34,252 families who all conscripted during the study period, the negative association between exposure to birth by any CS with levels of CRF later in life initially found in our main analysis inverted to a statistically significant positive association after fully adjusting for covariates.

Interpretation of findings

Our main analysis captured a modest but statistically significant association between birth by CS and lower levels of CRF. However, this negative association between CS with levels of CRF later in life inverted when accounting for genetic and environmental factors and our linear regression within-family model estimated a positive association between birth by any CS and Wmax after fully adjusting for covariates. Rather than overreaching in our interpretation of the relevance of this positive association, which we consider more sporadic in nature than clinically relevant, we interpret the findings of our within-family analyses to indicate a full attenuation of the negative association between birth by CS with lower levels of CRF later in life as initially indicated in our main analysis.

Thus, residual confounding capable of explaining the negative association found in our main analysis is relevant to consider in this context. Firstly, it is known that physical activity (PA) in adult populations in high Human Development Index (HDI) countries is positively associated with socioeconomic position, with a stronger impact in the first half of one’s lifetime53,54,55,56. In turn, low to moderate physical exercise during pregnancy, particularly in the second and third trimester, has been shown to reduce the risk for cesarean delivery57,58. In addition, maternal obesity is a known indication of CS in general and elective CS in particular, and is strongly inversely associated with both socioeconomic position and PA, particularly in high-HDI countries59,60. That is to say, although we controlled for socioeconomic position through a range of relevant covariates it is possible that our main analyses are still impacted by unmeasured residual socioeconomic confounding. Secondly, another possibility is that shared genetic predisposition and behavioral modulators of CRF phenotype in our within-family analysis accounts for the attenuation observed. CRF phenotype is a strong gender-independent predictor of individual mortality and morbidity independent of PA-levels61. Although CRF is subject to genetic predisposition, it is also clearly subject to modulation through behavioral attitudes towards PA participation and physiological factors62. By thus comparing biological siblings in our within-family analysis the shared genetic predisposition for CRF phenotype as well as the shared behavioral and physiological modulating factors of CRF could thus all contribute towards the attenuation. If genetic predisposition for CRF phenotype would also have a bearing on the probability of a CS delivery, for example via maternal obesity63, it could be material in explaining our within-family attenuation. E-values for our estimates indicate that an unmeasured confounder that increased the odds of the outcome by 26% in either the exposed or unexposed group, and if that unmeasured confounder was 26% more prevalent among the exposed than the unexposed, would suffice to fully attenuate the association64,65. Altogether, analysis of the available data on balance does not support the likelihood of a causal link between birth by CS and low levels of CRF later in life. Instead it favors an interpretation where residual confounding, possibly socioeconomic or genetic in nature, likely accounts for the initially observed associations that attenuate across within-family analyses where individuals exposed to the same socioeconomic and genetic modulators of CRF are compared.

Clinical relevance

Rapidly increasing global incidence of CS makes systematic investigation of offspring health outcomes associated with birth by CS a growing area of interest for public health. Of particular importance is exploration of associations between CS and gender-independent predictors of long-term survival and all-cause mortality suitable for intervention. Besides genetic predisposition for disease-specific morbidities, CRF is perhaps one of the stronger known predictors of long-term survival that it lends itself to policy-driven intervention at the population-level to improve public health outcomes24,25,26,27,28,29,30,66. We used Wmax as a validated proxy outcome for CRF and did not find any associations between birth by CS and CRF in the eighteenth life-year that was not completely explained by factors of familial confounding.

Wmax has been repeatedly validated in the literature as a close correlate of maximal oxygen uptake (VO2 max) and is considered a relevant proxy for measuring CRF67,68,69. Wmax can be used to estimate VO2 max using formulaic methodology that allows for CRF comparisons across VO2 max which is the global standard of CRF36. In our study we defined low CRF as the lowest quartile of recruits in terms of Wmax achieved, and this translated to a Wmax cut-off value of 270 W. Converting our low CRF cut-off value into VO2 max for a young adolescent weighing 75 kg would correspond to around 42.3 mL/kg/min and is in-line with the 42 mL/kg/min VO2 max cut-offs proposed in the literature for identifying adolescents with increased risk of cardiovascular disease70.

Strengths and limitations

The use of a validated and objectively measured proxy for CRF collected in a standardized test environment, access to high-quality national registers with broad data ranges and total population coverage, the large sample size and long-term follow-up are major strengths of this study. The ability to differentiate between elective and non-elective CS in a large sub-population of males born 1982–1987 is a medically relevant strength as both indications and risk-profiles differ and thus control for a potential source of confounding by indication. Adjustments of a wide range of possible socioeconomic confounders in conjunction with our within-family analysis that likely captures additional unmeasured residual socioeconomic confounding contribute to the robustness of our conclusions.

Yet, residual confounding can never be excluded in an observational study and there are limitations that must be considered. Firstly, our analytic sample contains only males due to sex-biased conscription legislation in Sweden during the study period. Secondly, although within-family analyses are robust to unobserved shared familial confounding they are still sensitive to non-shared confounding71, shared-mediators72, and measurement error71. While we believe measurement errors in our outcome are minimal due to the standardized nature of data collection and even though we controlled for non-shared observed confounding, caution may still be warranted when directly interpreting coefficients from sibling analyses. Thirdly, our findings are potentially limited by exclusion bias. Notwithstanding those excluded because of incomplete or missing data at birth, a total of 372,552 males were excluded because they were either not called upon for conscription or were not allowed to perform the CRF test for various medical reasons. Among those excluded we observe a significantly higher proportion of CS births (11.3%) compared to those who conscripted (9.8%) and our main analytic sample (8.8%) as well as a clear trend towards lower socioeconomic position, particularly in those not invited for conscription, Supplementary Table S4. As a result, our final analytic sample covers only about 44.5% of the total male population born between 1973–1987 and must be considered as significantly healthier and possibly hailing from higher socioeconomic positions compared to the general population. That is to say that while our findings are representative for a large population of healthy Swedish males it is likely that those excluded from our study somehow differ systematically which may lead to an underestimation of a potential causal effect of CS on CRF later in life. Lastly, our data coverage did not include PA-data on recruits which meant that we were unable investigate a possible role of PA in the relationship between CS and CRF.

Conclusions

Our analysis captured modest but statistically significant population-level associations between exposure to birth by CS and lower levels of CRF in the eighteenth life-year. However, these associations attenuated fully in our within-family analyses which take into account factors of familial confounding such as genetic and socioeconomic modulators of CRF. Further research into the possible impact of birth by CS on CRF later in life, particularly in the female population, is warranted and could be of value to public health.

Data availability

Due to Swedish legal restrictions and the existing ethical approval for this study, data will not be made publically available. The research group can provide descriptive data in table form.

Abbreviations

- CS:

-

Cesarean section

- CRF:

-

Cardiorespiratory fitness

- Wmax:

-

Watt-maximum

- MBR:

-

The Swedish medical birth register

- PHC:

-

The population and housing censuses

- BMI:

-

Body-mass index

- aOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- PA:

-

Physical activity

- HDI:

-

Human development index

- VO2 max:

-

Maximal oxygen uptake

References

Boatin, A. A. et al. Within country inequalities in caesarean section rates: Observational study of 72 low and middle income countries. BMJ 360, k55. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k55 (2018).

Betran, A. P. et al. The increasing trend in caesarean section rates: Global, regional and national estimates: 1990–2014. PLoS ONE 11, e0148343. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0148343 (2016).

Barber, E. L. et al. Indications contributing to the increasing cesarean delivery rate. Obstet. Gynecol. 118, 29–38. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e31821e5f65 (2011).

Torloni, M. R. et al. Portrayal of caesarean section in Brazilian women’s magazines: 20 year review. BMJ 342, d276. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d276 (2011).

Treffers, P. E. & Pel, M. The rising trend for caesarean birth. BMJ 307, 1017–1018. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.307.6911.1017 (1993).

Betran, A. P., Torloni, M. R., Zhang, J. J. & Gulmezoglu, A. M. WHO statement on caesarean section rates. BJOG 123, 667–670. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.13526 (2016).

Betran, A. P. et al. What is the optimal rate of caesarean section at population level? A systematic review of ecologic studies. Reprod. Health 12, 57. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-015-0043-6 (2015).

8Ye, J., Betran, A. P., Guerrero Vela, M., Souza, J. P. & Zhang, J. Searching for the optimal rate of medically necessary cesarean delivery. Birth 41, 237–244, https://doi.org/10.1111/birt.12104 (2014).

Kietpeerakool, C. et al. Pregnancy outcomes of women with previous caesarean sections: Secondary analysis of World Health Organization multicountry survey on maternal and newborn health. Sci. Rep. 9, 9748. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-46153-4 (2019).

Keag, O. E., Norman, J. E. & Stock, S. J. Long-term risks and benefits associated with cesarean delivery for mother, baby, and subsequent pregnancies: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 15, e1002494. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002494 (2018).

Motomura, K. et al. Incidence and outcomes of uterine rupture among women with prior caesarean section: WHO multicountry survey on maternal and newborn health. Sci. Rep. 7, 44093. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep44093 (2017).

Silver, R. M. Abnormal placentation: Placenta previa, vasa previa, and placenta accreta. Obstet. Gynecol. 126, 654–668. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0000000000001005 (2015).

Gregory, K. D., Jackson, S., Korst, L. & Fridman, M. Cesarean versus vaginal delivery: Whose risks? Whose benefits?. Am. J. Perinatol. 29, 7–18. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0031-1285829 (2012).

Lumbiganon, P. et al. Method of delivery and pregnancy outcomes in Asia: the WHO global survey on maternal and perinatal health 2007–08. Lancet 375, 490–499. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(09)61870-5 (2010).

Shah, A. et al. Cesarean delivery outcomes from the WHO global survey on maternal and perinatal health in Africa. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 107, 191–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2009.08.013 (2009).

Liu, S. et al. Maternal mortality and severe morbidity associated with low-risk planned cesarean delivery versus planned vaginal delivery at term. CMAJ 176, 455–460. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.060870 (2007).

Villar, J. et al. Caesarean delivery rates and pregnancy outcomes: The 2005 WHO global survey on maternal and perinatal health in Latin America. Lancet 367, 1819–1829. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(06)68704-7 (2006).

Ahlqvist, V. H., Persson, M., Magnusson, C. & Berglind, D. Elective and nonelective cesarean section and obesity among young adult male offspring: A Swedish population-based cohort study. PLoS Med. 16, e1002996. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002996 (2019).

Rifas-Shiman, S. L. et al. Association of cesarean delivery with body mass index z score at age 5 years. JAMA Pediatr. 172, 777–779. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.0674 (2018).

Masukume, G. et al. The impact of caesarean section on the risk of childhood overweight and obesity: New evidence from a contemporary cohort study. Sci. Rep. 8, 15113. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-33482-z (2018).

Yuan, C. et al. Association between cesarean birth and risk of obesity in offspring in childhood, adolescence, and early adulthood. JAMA Pediatr. 170, e162385. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.2385 (2016).

Kuhle, S., Tong, O. S. & Woolcott, C. G. Association between caesarean section and childhood obesity: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes. Rev. 16, 295–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12267 (2015).

Bager, P., Wohlfahrt, J. & Westergaard, T. Caesarean delivery and risk of atopy and allergic disease: Meta-analyses. Clin. Exp. Allergy 38, 634–642. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2222.2008.02939.x (2008).

Mandsager, K. et al. Association of cardiorespiratory fitness with long-term mortality among adults undergoing exercise treadmill testing. JAMA Netw. Open 1, e183605. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.3605 (2018).

Laukkanen, J. A. et al. Long-term change in cardiorespiratory fitness and all-cause mortality: A population-based follow-up study. Mayo Clin. Proc. 91, 1183–1188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.05.014 (2016).

Erikssen, G. et al. Changes in physical fitness and changes in mortality. Lancet 352, 759–762. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(98)02268-5 (1998).

Cao, C. et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness is associated with early death among healthy young and middle-aged baby boomers and generation xers. Am. J. Med. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.12.041 (2020).

Harber, M. P. et al. Impact of cardiorespiratory fitness on all-cause and disease-specific mortality: Advances since 2009. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 60, 11–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2017.03.001 (2017).

Hogstrom, G., Nordstrom, A. & Nordstrom, P. Aerobic fitness in late adolescence and the risk of early death: A prospective cohort study of 1.3 million Swedish men. Int. J. Epidemiol. 45, 1159–1168, https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyv321 (2016).

Kodama, S. et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness as a quantitative predictor of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events in healthy men and women: A meta-analysis. JAMA 301, 2024–2035. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.681 (2009).

Nocon, M. et al. Association of physical activity with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Cardiovasc. Prev. Rehabil. 15, 239–246. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJR.0b013e3282f55e09 (2008).

Evenson, K. R., Stevens, J., Thomas, R. & Cai, J. Effect of cardiorespiratory fitness on mortality among hypertensive and normotensive women and men. Epidemiology 15, 565–572. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ede.0000129527.53181.c8 (2004).

Church, T. S., Kampert, J. B., Gibbons, L. W., Barlow, C. E. & Blair, S. N. Usefulness of cardiorespiratory fitness as a predictor of all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality in men with systemic hypertension. Am. J. Cardiol. 88, 651–656. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9149(01)01808-2 (2001).

Ludvigsson, J. F., Otterblad-Olausson, P., Pettersson, B. U. & Ekbom, A. The Swedish personal identity number: Possibilities and pitfalls in healthcare and medical research. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 24, 659–667. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10654-009-9350-y (2009).

Cnattingius, S., Ericson, A., Gunnarskog, J. & Kallen, B. A quality study of a medical birth registry. Scand. J. Soc. Med. 18, 143–148. https://doi.org/10.1177/140349489001800209 (1990).

Kokkinos, P., Kaminsky, L. A., Arena, R., Zhang, J. & Myers, J. A new generalized cycle ergometry equation for predicting maximal oxygen uptake: The Fitness Registry and the Importance of Exercise National Database (FRIEND). Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 25, 1077–1082. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487318772667 (2018).

Ahlqvist, V. H. et al. Birth weight and cardiorespiratory fitness among young men born at term: The role of genetic and environmental factors. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 9, e014290. https://doi.org/10.1161/jaha.119.014290 (2020).

Ferreira, I., Gbatu, P. T. & Boreham, C. A. Gestational age and cardiorespiratory fitness in individuals born at term: A life course study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 6, https://doi.org/10.1161/jaha.117.006467 (2017).

Myrskyla, M. & Fenelon, A. Maternal age and offspring adult health: Evidence from the health and retirement study. Demography 49, 1231–1257. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-012-0132-x (2012).

Reynolds, R. M., Osmond, C., Phillips, D. I. & Godfrey, K. M. Maternal BMI, parity, and pregnancy weight gain: Influences on offspring adiposity in young adulthood. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 95, 5365–5369. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2010-0697 (2010).

Tam, W. H. et al. In utero exposure to maternal hyperglycemia increases childhood cardiometabolic risk in offspring. Diabetes Care 40, 679–686. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc16-2397 (2017).

Lindsay, R. S., Hanson, R. L., Bennett, P. H. & Knowler, W. C. Secular trends in birth weight, BMI, and diabetes in the offspring of diabetic mothers. Diabetes Care 23, 1249–1254. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.23.9.1249 (2000).

Fraser, A., Nelson, S. M., Macdonald-Wallis, C., Sattar, N. & Lawlor, D. A. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and cardiometabolic health in adolescent offspring. Hypertension 62, 614–620. https://doi.org/10.1161/hypertensionaha.113.01513 (2013).

44Fox, R., Kitt, J., Leeson, P., Aye, C. Y. L. & Lewandowski, A. J. Preeclampsia: Risk factors, diagnosis, management, and the cardiovascular impact on the offspring. J. Clin. Med. 8, https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8101625 (2019).

Bokslag, A., van Weissenbruch, M., Mol, B. W. & de Groot, C. J. Preeclampsia; short and long-term consequences for mother and neonate. Early Hum. Dev. 102, 47–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2016.09.007 (2016).

Mehta, B. et al. Trends in maternal and fetal outcomes among pregnant women with systemic lupus erythematosus in the United States. Ann. Intern. Med. 171, 164–171. https://doi.org/10.7326/M19-0120 (2019).

Yengej, F. A. Y., van Royen-Kerkhof, A., Derksen, R. H. & Fritsch-Stork, R. D. The development of offspring from mothers with systemic lupus erythematosus. A systematic review. Autoimmun. Rev. 16, 701–711 (2017).

Mintjens, S. et al. Maternal prepregnancy overweight and obesity are associated with reduced physical fitness but do not affect physical activity in childhood: The Amsterdam born children and their development study. Child Obes. 15, 31–39. https://doi.org/10.1089/chi.2018.0171 (2019).

Hagnas, M. P. et al. Association of maternal smoking during pregnancy with aerobic fitness of offspring in young adulthood: A prospective cohort study. BJOG 123, 1789–1795. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.13789 (2016).

Baba, S., Wikstrom, A. K., Stephansson, O. & Cnattingius, S. Changes in snuff and smoking habits in Swedish pregnant women and risk for small for gestational age births. BJOG 120, 456–462. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.12067 (2013).

Harrell, F. Regression modeling strategies. BIOS 330, 2018 (2017).

Johansson, K., Hutcheon, J. A., Stephansson, O. & Cnattingius, S. Pregnancy weight gain by gestational age and BMI in Sweden: A population-based cohort study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 103, 1278–1284. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.115.110197 (2016).

Zujko, M. E. et al. Dietary habits and dietary antioxidant intake are related to socioeconomic status in Polish adults: A nationwide study. Nutrients 12, https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12020518 (2020).

Lee, H. H., Perez, A. E. & Operario, D. Age moderates the effect of socioeconomic status on physical activity level among south Korean adults: Cross-sectional analysis of nationally representative sample. BMC Public Health 19, 1332. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7610-7 (2019).

Puciato, D. et al. Physical activity of working-age people in view of their income status. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 8298527. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/8298527 (2018).

Lin, C. H. et al. Influence of socioeconomic status and perceived barriers on physical activity among Taiwanese middle-aged and older women. J. Cardiovasc. Nurs. 32, 321–330. https://doi.org/10.1097/jcn.0000000000000354 (2017).

Poyatos-Leon, R. et al. Effects of exercise during pregnancy on mode of delivery: A meta-analysis. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 94, 1039–1047. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.12675 (2015).

Domenjoz, I., Kayser, B. & Boulvain, M. Effect of physical activity during pregnancy on mode of delivery. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 211(401), e401-411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2014.03.030 (2014).

Volaco, A., Cavalcanti, A. M., Filho, R. P. & Precoma, D. B. Socioeconomic status: The missing link between obesity and diabetes mellitus?. Curr. Diabetes Rev. 14, 321–326. https://doi.org/10.2174/1573399813666170621123227 (2018).

McLaren, L. Socioeconomic status and obesity. Epidemiol. Rev. 29, 29–48. https://doi.org/10.1093/epirev/mxm001 (2007).

Davidson, T., Vainshelboim, B., Kokkinos, P., Myers, J. & Ross, R. Cardiorespiratory fitness versus physical activity as predictors of all-cause mortality in men. Am. Heart J. 196, 156–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2017.08.022 (2018).

Taylor, M. K., Hernández, L. M., Schoenherr, M. R. & Stump, E. J. Genetic, physiologic, and behavioral predictors of cardiorespiratory fitness in specialized military men. Mil. Med. 184, e474–e481. https://doi.org/10.1093/milmed/usz033 (2019).

Schnurr, T. M. et al. Genetic correlation between body fat percentage and cardiorespiratory fitness suggests common genetic etiology. PLoS ONE 11, e0166738. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0166738 (2016).

Mathur, M. B., Ding, P., Riddell, C. A. & VanderWeele, T. J. Web site and R package for computing E-values. Epidemiology 29, e45–e47. https://doi.org/10.1097/ede.0000000000000864 (2018).

VanderWeele, T. J. & Ding, P. Sensitivity analysis in observational research: Introducing the E-value. Ann. Intern. Med. 167, 268–274. https://doi.org/10.7326/m16-2607 (2017).

Pandey, A. et al. Short-term changes in cardiorespiratory fitness in response to exercise training and the association with long-term cardiorespiratory fitness decline: The STRRIDE reunion study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 8, e012876. https://doi.org/10.1161/jaha.119.012876 (2019).

Kaminsky, L. A. et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness and cardiovascular disease—The past, present, and future. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 62, 86–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2019.01.002 (2019).

Sorensen, J. B., Kragstrup, J., Kjaer, K. & Puggaard, L. Exercise on prescription: Trial protocol and evaluation of outcomes. BMC Health Serv. Res. 7, 36. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-7-36 (2007).

Arts, F. J. & Kuipers, H. The relation between power output, oxygen uptake and heart rate in male athletes. Int. J. Sports Med. 15, 228–231. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2007-1021051 (1994).

Ruiz, J. R. et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness cut points to avoid cardiovascular disease risk in children and adolescents; what level of fitness should raise a red flag? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Sports Med. 50, 1451–1458. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2015-095903 (2016).

Frisell, T., Oberg, S., Kuja-Halkola, R. & Sjolander, A. Sibling comparison designs: Bias from non-shared confounders and measurement error. Epidemiology 23, 713–720. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0b013e31825fa230 (2012).

Sjolander, A. & Zetterqvist, J. Confounders, mediators, or colliders: What types of shared covariates does a sibling comparison design control for?. Epidemiology 28, 540–547. https://doi.org/10.1097/ede.0000000000000649 (2017).

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Karolinska Institute. DB is guarantor for the study and is funded by the Stockholm County Council (ALF 20180266).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors meet the ICMJE-criteria for authorship, contributed critically in terms of conception and planning of the study, analysis and reporting of the data and have given final approval for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ekstrom, L.D., Ahlqvist, V.H., Persson, M. et al. The association between birth by cesarean section and adolescent cardiorespiratory fitness in a cohort of 339,451 Swedish males. Sci Rep 10, 18661 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-75775-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-75775-2

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.