Abstract

Metabolic syndrome is characterized by central obesity, insulin resistance, elevated blood pressure, and dyslipidemia. Metabolic syndrome is a significant risk factor for several common cancers (e.g., liver, colorectal, breast, pancreas). Pharmacologic treatments used for the components of the metabolic syndrome appear to be insufficient to control cancer development in subjects with metabolic syndrome. Murine models showed that cancer has the slowest progression when there is no food consumption during the daily activity phase. Intermittent fasting from dawn to sunset is a form of fasting practiced during human activity hours. To test the anticancer effect of intermittent fasting from dawn to sunset in metabolic syndrome, we conducted a pilot study in 14 subjects with metabolic syndrome who fasted (no eating or drinking) from dawn to sunset for more than 14 h daily for four consecutive weeks. We collected serum samples before 4-week intermittent fasting, at the end of 4th week during 4-week intermittent fasting and 1 week after 4-week intermittent fasting. We performed serum proteomic analysis using nano ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. We found a significant fold increase in the levels of several tumor suppressor and DNA repair gene protein products (GP)s at the end of 4th week during 4-week intermittent fasting (CALU, INTS6, KIT, CROCC, PIGR), and 1 week after 4-week intermittent fasting (CALU, CALR, IGFBP4, SEMA4B) compared with the levels before 4-week intermittent fasting. We also found a significant reduction in the levels of tumor promoter GPs at the end of 4th week during 4-week intermittent fasting (POLK, CD109, CAMP, NIFK, SRGN), and 1 week after 4-week intermittent fasting (CAMP, PLAC1) compared with the levels before 4-week intermittent fasting. Fasting from dawn to sunset for four weeks also induced an anti-diabetes proteome response by upregulating the key regulatory proteins of insulin signaling at the end of 4th week during 4-week intermittent fasting (VPS8, POLRMT, IGFBP-5) and 1 week after 4-week intermittent fasting (PRKCSH), and an anti-aging proteome response by upregulating H2B histone proteins 1 week after 4-week intermittent fasting. Subjects had a significant reduction in body mass index, waist circumference, and improvement in blood pressure that co-occurred with the anticancer, anti-diabetes, and anti-aging serum proteome response. These findings suggest that intermittent fasting from dawn to sunset actively modulates the respective genes and can be an adjunct treatment in metabolic syndrome. Further studies are needed to test the intermittent fasting from dawn to sunset in the prevention and treatment of metabolic syndrome-induced cancers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

One of the grand challenges of our times is the rising prevalence of metabolic syndrome1. Metabolic syndrome is characterized by central obesity, insulin resistance, elevated blood pressure, high triglyceride, and low high-density lipoprotein levels2. Metabolic syndrome has adversely impacted many aspects of society3. Importantly, metabolic syndrome is a significant risk factor for several common cancers (e.g., liver, colorectal, breast, endometrium, pancreas)4,5.

Disrupted circadian clock rhythm has been recognized as one of the causes of metabolic syndrome and metabolic syndrome-induced cancers6,7,8. Pharmacologic treatments used for the components of the metabolic syndrome appear to be insufficient to reduce the risk of developing metabolic syndrome-induced cancers9. Moreover, pharmacologic treatments cannot reset the circadian clock rhythm; thus, there is an urgent need for an effective intervention to reset the circadian clock and prevent metabolic syndrome and metabolic syndrome-induced cancers. Animal studies showed that resetting the circadian clock by time-restricted feeding improves metabolic syndrome and inhibits the development of cancer10,11. Therefore, resetting the disrupted circadian clock in humans by consecutive daily intermittent fasting could provide a primary strategy to improve metabolic syndrome and reduce the incidence of metabolic syndrome-induced cancer10,11,12. Fasting during activity hours in contrast to the inactivity hours of the day appears to be important for the optimization of anticancer effect and gene expression. Mice with no access to food during the activity phase (dark phase) of a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle had a significantly slower tumor progression and higher survival compared with mice that had no access to food during the inactivity phase (light phase), and mice that had access to food ad libitum13. Consistent with these findings, an earlier murine study showed that the uncoupling of the peripheral clocks from the control of the central clock only occurred when mice had no access to food during the active phase14. In contrast, a minimal change in the phase of gene expression was observed when mice had no access to food during the inactive phase14, corresponding to night time in humans. The findings of murine studies should be interpreted in the context of the fact that humans are diurnal (activity occurs during daytime), and mice are nocturnal (activity occurs during nighttime). The findings of these murine studies are in accord with the findings of our preliminary studies conducted in healthy subjects15. Our results showed that 30-day intermittent fasting from dawn to sunset, the human activity phase, was associated with an anticancer serum proteome response and upregulated several key regulatory proteins that play a key role in tumor suppression, DNA repair, insulin signaling, glucose, and lipid metabolism, circadian clock, cytoskeletal remodeling, immune system, and cognitive function15. Importantly, the increase in the levels of these critical regulatory proteins occurred in the absence of any significant weight loss and calorie restriction15. Several human studies showed beneficial effects of intermittent fasting (e.g., Ramadan fasting16,17,18), and time-restricted eating19 in subjects with metabolic syndrome. However, in none of these studies, proteomic profiling was performed to understand the mechanism behind the anticancer effect of intermittent fasting and time-restricted eating in subjects with metabolic syndrome.

To this end, we hypothesized that intermittent fasting from dawn to sunset practiced exclusively during the human activity hours for four weeks would be associated with an anticancer serum proteome response, upregulate anticancer proteins and regulatory proteins of DNA repair and insulin signaling, and downregulate pro-cancer proteins.

Methods

Study subjects

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Baylor College of Medicine Biomedical Research and Assurance Information Network (BRAIN) under protocol number H-31612. All research was conducted in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations after written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. The study did not qualify for prospective registration as a clinical trial because there was no study directed intervention. The religious fast was habitual personal conduct, not study directed, and as such, the study was observational in study design. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Subjects who are 18 years old or older; (2) Subjects who plan to fast during the religious month of Ramadan16; (3) Subjects should meet any three of the following five criteria for metabolic syndrome as described by Grundy et al.2 (a) central obesity assessed by waist circumference equal to or greater than 102 cm (40 inches) in men, and equal or greater than 88 cm (35 inches) in women; (b) fasting serum triglyceride level equal to or greater than 150 mg/dL or on drug therapy for hypertriglyceridemia (e.g., fibrates, nicotinic acid); (c) low high-density lipoprotein level less than 40 mg/dL in men and less than 50 mg/dL in women or on drug therapy for low high-density lipoprotein level (fibrates, nicotinic acid); (d) elevated systolic blood pressure equal to or greater than 130 or elevated diastolic blood pressure equal to or greater than 85 or on drug therapy for hypertension, (e) elevated fasting glucose level equal to or greater than 100 mg/dL or on drug therapy for hyperglycemia/diabetes); (4) Subjects who agreed to undergo FibroScan20 testing for evaluation of hepatic steatosis and fibrosis20. Subjects were excluded if they had any of the following: (1) inability to provide informed consent; (2) women who are pregnant or breastfeeding; (3) active cancer; (4) active infection requiring antibiotic use; (5) seizure disorder; (6) cardiovascular event during the last 6 months; (7) use of alcohol or recreational substances.

The primary outcome of this pilot study was the induction of an anticancer proteome response at the end of 4th week during 4-week intermittent fasting and 1 week after 4-week intermittent fasting. The secondary outcomes were improvement in the components of metabolic syndrome, lipid panel (total cholesterol, triglyceride, high-density lipoprotein, and low-density lipoprotein), hepatic panel (albumin, total protein, alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase), and adiposity, oxidative stress, and inflammation biomarkers.

Study procedures

Subjects were scheduled for a screening visit within three weeks of initiation of 4-week intermittent fasting at Baylor College of Medicine in the Texas Medical Center Digestive Diseases Center Clinical Research Core E Laboratory. During this visit, their eligibility was assessed based on inclusion and exclusion criteria, and written informed consent was taken. Medical history and physical examination were performed. Blood pressure measurements were performed at rest and sitting position. A urine pregnancy test for the female subjects at childbearing age was performed.

Hepatic steatosis and fibrosis were assessed using FibroScan with a controlled attenuation parameter (CAP)20.

Subjects started fasting at dawn after a pre-dawn breakfast and ended fasting at sunset (dusk) with a dinner for 29 consecutive days. Strict fasting occurred without eating or drinking between dawn and sunset (dusk), which are symmetrical transition time zones of the day. There was no interventional calorie or energy restriction otherwise. Subjects had their main meals at the transition time zones of the day, including pre-dawn breakfast (at the first transition time of the day) and dinner at sunset (at the second transition time of the day) and were allowed to eat (e.g., snacks) or drink if they needed between sunset and dawn in addition to the pre-dawn breakfast and dinner at sunset.

Data on weight, waist circumference and blood pressure and blood specimens were collected within three weeks before the initiation of 4-week intermittent fasting to assess the effect of ad libitum eating, at the end of 4th week during 4-week intermittent fasting to assess the effect of intermittent fasting and 1 week after 4-week intermittent fasting to assess the carryover effect of intermittent fasting on serum proteome, components of metabolic syndrome, lipid and hepatic panels, and adiposity, oxidative stress, and inflammation biomarkers. At each time point, data on weight, waist circumference, and blood pressure and blood specimens were collected after at least 8 h of fasting.

The compliance with fasting was monitored by a 13C-isotopic breath enrichment test, as previously described15,21.

Serum proteomics

We previously described a robust, streamlined proteomic approach to perform quantitative analysis of human serum samples using nano ultra-highperformance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (nano UHPLC-MS/MS)15. Briefly, 10 μl of serum was incubated with the top 12 abundant serum protein depletion kit (Thermo Scientific Pierce, Cat# 85164) and digested with trypsin on S-Trap column (ProtiFi, NY). The digested peptide was eluted, vacuum dried, and fractionated using high pH STAGE (Stop-and-go extraction) method into two pools, then subjected to nano-HPLC–MS/MS analysis. The parameters for mass spectrometry analysis and the process for mass analysis is maintained the same as previous publication15. We also explained the details of the gene protein product (GP)s quantification in our previous publication15. Briefly, we quantified GPs using the label-free, intensity-based absolute quantification (iBAQ) method and then normalized to final quantificational value (FOT) defined as the iBAQ value of an individual protein divided by the total iBAQ values of all identified proteins within one experiment. The FOT represents the relative abundance of each GP. The FOT values of a particular GP in different conditions (e.g., FOT value of a GP before 4-week intermittent fasting and at the end of 4th week during 4-week intermittent fasting) can be divided to get a fold change. FOT value also provides the relative quantification of different GPs in the same condition (e.g., FOT value of two different GPs at the end of 4th week during 4-week intermittent fasting).

Statistical analysis

For statistical analysis of serum proteomics, we used Excel application (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA). To determine statistically significantly regulated protein levels at the end of 4th week during 4-week intermittent fasting and 1 week after 4-week intermittent fasting, we performed paired two-tailed student’s t-test using log converted iFOT values15. We considered protein levels that showed an equal to or greater than fourfold average paired change and a P value of < 0.05 as significant15. We performed a volcano plot analysis to display the GPs that had an equal to or greater than fourfold significant change at the end of 4-week intermittent fasting during 4-week intermittent fasting and 1 week after 4-week intermittent fasting compared with the levels before 4-week intermittent fasting15.

Components of metabolic syndrome, lipid and hepatic panels, adiposity, oxidative stress and inflammation biomarkers

We measured the components of metabolic syndrome, lipid panel, hepatic panel and adiposity, oxidative stress, and inflammation biomarkers within three weeks before 4-week intermittent fasting, at the end of 4-week intermittent fasting during 4-week intermittent fasting, and 1 week after 4-week intermittent fasting. We estimated the insulin resistance by using Homeostatic Model Assessment for Insulin Resistance (HOMA-IR) equation as described by Matthews et al.22 We calculated the mean arterial blood pressure using the following formula: (diastolic blood pressure) + [(systolic blood pressure-diastolic blood pressure)/3]23.

Statistical analysis

We used SAS Version 9.4 TS Level 1M5 X64_10PRO platform (SAS, Cary, NC, USA)24 to perform statistical analysis of the components of metabolic syndrome, lipid panel, hepatic panel, and adiposity, oxidative stress, and inflammation biomarkers. We performed a student’s paired t-test to determine statistically significant changes in the levels of the components of metabolic syndrome, lipid panel, hepatic panel, and adiposity, oxidative stress, and inflammation biomarkers measured at the end of 4th week during 4-week intermittent fasting, and 1 week after 4-week intermittent fasting. We calculated Pearson’s correlation coefficient to assess correlations between significant GPs (i.e., GPs that showed significant fold changes at the end of 4th week during 4-week intermittent fasting and 1 week after 4-week intermittent fasting) and the components of metabolic syndrome, lipid panel, hepatic panel, and adiposity, oxidative stress, and inflammation biomarkers. In these analyses, we considered a two-tailed P value of ˂ 0.05 statistically significant.

Results

Subjects

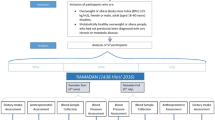

We enrolled 14 subjects with metabolic syndrome (8 males:6 females) with a mean age of 59 years (SD = 16). All subjects fasted for more than 14 h daily for 29 days beginning from May 06, 2019, until June 03, 2019 (Fig. 1). Mean FibroScan CAP was 286 (SD = 77) dB/m, and the mean elastic modulus was 9.7 (SD = 8.4) kPa. Ten subjects had moderate to severe hepatic steatosis (S2–S3), two had mild hepatic steatosis (S1), and two had no hepatic steatosis (S0). Two subjects had F4 hepatic fibrosis, two had F3 hepatic fibrosis, one had F2 hepatic fibrosis, and nine had F0–F1 hepatic fibrosis. Nine subjects were on anti-hypertensive medications; seven subjects were on antidiabetic medications, and six subjects were on statins.

Intermittent fasting from dawn to sunset (dusk) for four weeks. Subjects fasted (no eating or drinking) for more than 14 h. daily for 29 days, from May 06, 2019, until June 03, 2019. The minimum required duration of daily fasting from dawn to sunset was 14 h., 8 min for the shortest day (May 6, 2019), and 14 h., 42 min for the longest day (June 03, 2019). Ramadan fasting is a unique form of intermittent fasting from dawn to sunset (dusk) without eating or drinking during the month of Ramadan based on the lunar calendar16 and has several major unique features: (1) Fasting is exclusively practiced during the human activity hours from dawn to sunset and is for both eating and drinking, which differentiates the dawn to sunset intermittent fasting from the other forms of intermittent fasting where eating light meals and/or drinking are allowed during the fasting window; (2) Although the main meals are at transition time zones of the day (pre-dawn breakfast and dinner at sunset), eating and drinking outside these transition time zones is allowed as long as it is within the non-fasting window; (3) There is no interventional calorie or energy restriction; (4) Daily fasting window is in synchrony with circadian rhythm and earth’s rotation on its axis because the daily fast starts at dawn (the first transition time zone of the day) after a pre-dawn breakfast and ends at sunset (dusk) (the second transition time zone of the day) with dinner; (5) Monthly fasting window is in synchrony with the moon’s rotation around the earth and lunar phases because the monthly fasting starts and ends when the new moon is sighted (with permission from Baylor College of Medicine).

The minimum required duration of daily fasting from dawn to sunset (dusk) was 14 h, 8 min for the shortest day (May 6, 2019), and 14 h, 42 min for the longest day (June 03, 2019). All subjects tolerated intermittent fasting well without any complications.

The components of metabolic syndrome, lipid and hepatic panels, and adiposity, oxidative stress and inflammation biomarkers

Table 1 shows the mean levels of the components of metabolic syndrome, lipid panel, hepatic panel, and adiposity, oxidative stress, and inflammation biomarkers before 4-week intermittent fasting and their mean paired changes at the end of 4th week during 4-week intermittent fasting and 1 week after 4-week intermittent fasting. There was a significant reduction in weight (P < 0.0001), body mass index (P < 0.0001), waist circumference (P = 0.006), systolic (P = 0.023), diastolic (P = 0.002) and mean (P = 0.002) arterial blood pressures at the end of 4th week during 4-week intermittent fasting and a significant reduction in weight (P < 0.0001), body mass index (P < 0.0001), waist circumference (P = 0.021) and HOMA-IR (P = 0.035) 1 week after 4-week intermittent fasting compared with the levels before 4-week intermittent fasting. We observed a reduction in insulin, glucose, HOMA-IR, triglyceride, leptin, and several oxidative stress and inflammation biomarker levels and an increase in high-density lipoprotein and adiponectin levels at the end of 4th week during 4-week intermittent fasting, however, these parameters did not reach statistical significance.

Serum proteomics

The proteome coverage and its dynamic order of average iFOT values from the samples taken at the end of 4th week during 4-week intermittent fasting are shown in Fig. 2A. There were 1219 GPs recovered with over eight orders of magnitude of dynamic range. There was a significant average paired fold change in the levels of several GPs at the end of 4th week during 4-week intermittent fasting compared with the levels before 4-week intermittent fasting (Supplementary Table S1). Figure 2A,B, and Table 2 show the selected ones from these GPs associated with tumor suppression, carcinogenesis, DNA repair, and insulin signaling. There was an average 74-fold increase in adaptor related protein complex 5 subunit zeta 1 (AP5Z1) (log2 fold = 6.201, P = 0.005), 53 fold increase in VPS8 subunit of CORVET complex (VPS8) (log2 fold = 5.730, P = 0.043), 19 fold increase in integrator complex subunit 6 INTS6 (log2 fold = 4.234, P = 0.041), 18 fold increase in calumenin (CALU) (log2 fold = 4.135, P = 0.012), 16 fold increase in insulin-like growth factor binding protein 5 (IGFBP5) (log2 fold = 4.008, P = 0.015), tenfold increase in RNA polymerase mitochondrial (POLRMT) (log2 fold = 3.355, P = 0.020), sevenfold increase in KIT proto-oncogene receptor tyrosine kinase (KIT) (log2 fold = 2.891, P = 0.033), sevenfold increase in ciliary rootlet coiled-coil, rootletin (CROCC) (log2 fold = 2.742, P = 0.043), sixfold increase in polymeric immunoglobulin receptor (PIGR) (log2 fold = 2.684, P = 0.041) GP levels at the end of 4th week during 4-week intermittent fasting compared with the levels before 4-week intermittent fasting. We found significant decrease in DNA polymerase kappa (POLK) (log2 fold = − 2.987, P = 0.026), CD109 molecule (CD109) (log2 fold = − 3.977, P = 0.027), cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide (CAMP) (log2 fold = − 5.020, P = 0.012), nucleolar protein interacting with the FHA domain of MKI67 (NIFK) (log2 fold = − 5.048, P = 0.019) and serglycin (SRGN) (log2 fold = − 6.286, P = 0.009) GP levels compared with the levels before 4-week intermittent fasting.

Gene protein products (GP) recovered at the end of 4th week during 4-week intermittent fasting and one week after 4-week intermittent fasting. (A) Distribution of normalized relative GP amount and location of focused significantly increased or decreased proteins in serum samples taken at the end of 4th week during 4-week intermittent fasting shown in GP name and rank order. (B) Volcano plot shows selected GPs that had an equal to or greater than fourfold significant change (blue and red colors represent a significant decrease and increase in the levels of GPs, respectively) at the end of 4th week during 4-week intermittent fasting compared with the levels before 4-week intermittent fasting. (C) Distribution of normalized relative GP amount and location of focused significantly increased or decreased proteins in serum samples taken 1 week after 4-week intermittent fasting shown in GP name and rank order. (D) Volcano plot shows selected GPs that had an equal to or greater than fourfold significant change (blue and red colors represent a significant decrease and increase in the levels of GPs, respectively) 1 week after 4-week intermittent fasting compared with the levels before 4-week intermittent fasting.

The proteome coverage and its dynamic order from 14 samples collected 1 week after 4-week intermittent fasting are shown in Fig. 2C. There were 1216 GPs recovered with over eight orders of magnitude of dynamic range. There was a significant average paired fold change in the levels of several GPs 1 week after 4-week intermittent fasting compared with the levels before 4-week intermittent fasting (Supplementary Table S2). Figure 2C,D, and Table 2 show selected ones from these GPs associated with tumor suppression, carcinogenesis, insulin signaling, and prolonged lifespan. There was an average 73 fold increase in PRKCSH protein kinase C substrate 80 K–H (PRKCSH) (log2 fold = 6.191, P = 0.031), 33 fold increase CALU (log2 fold = 5.026, P = 0.007), 16 fold increase in calreticulin (CALR) (log2 fold = 3.958, P = 0.020), 13 fold increase in insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 4 (IGFBP4) (log2 fold = 3.728, P = 0.033), tenfold increase in semaphorin 4B (SEMA4B) (log2 fold = 3.386, P = 0.020), sixfold increase in H2B clustered histone 3 (HIST1H2BB) (log2 fold = 2.656, P = 0.044), H2B clustered histone 5 (HIST1H2BD) (log2 fold = 2.620, P = 0.044), and H2B clustered histone 1 (HIST1H2BA) (log2 fold = 2.565, P = 0.020). We found a significant reduction in cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide (CAMP) (log2 fold = − 3.743, P = 0.038) and placenta enriched 1 (PLAC1) (log2 fold = − 7.071, P = 0.032) GP levels 1 week after 4-week intermittent fasting compared with the levels before 4-week intermittent fasting.

There was a significant average paired fold change in the levels of several GPs 1 week after 4-week intermittent fasting compared with the levels at the end of 4th week during 4-week intermittent fasting (Supplementary Table S3). Supplementary Fig. 1 and Table 2 show the average paired fold changes in the selected GPs 1 week after 4-week intermittent fasting compared with the levels at the end of 4th week during 4-week intermittent fasting.

Correlations between GPs and metabolic syndrome components, lipid and hepatic panels, adiposity, oxidative stress, and inflammation biomarkers

Several GPs that showed significant average paired fold changes at the end of 4th week during 4-week intermittent fasting and 1 week after 4-week intermittent fasting were correlated with the components of metabolic syndrome, lipid and hepatic panels and adiposity, oxidative stress and inflammation biomarkers at the end of 4th week during 4-week intermittent fasting (Supplementary Table 4) and 1 week after 4-week intermittent fasting (Supplementary Table 5). There was no significant correlation between log2 fold changes in the selected proteins (gene names are displayed in Table 2) and changes in weight, waist circumference and body mass index at the end of 4th week during 4-week intermittent fasting and 1 week after 4-week intermittent fasting compared with baseline.

Discussion

We reported the results of the first human study of serum proteomics of 4-week intermittent fasting from dawn to sunset conducted in subjects with metabolic syndrome. The results showed that intermittent fasting from dawn to sunset for more than 14 h daily for four consecutive weeks induced a unique anticancer, anti-diabetes and anti-aging proteomic response (Table 2, Figs. 1 and 2), upregulated several regulatory proteins that play a key role in tumor suppression, DNA repair, humoral defense, insulin signaling, and downregulated several tumor promotor proteins. These changes in protein expression are likely related to the reset of the circadian clock rhythm by intermittent fasting from dawn to sunset and in line with the results of previous murine studies13,14.

Intermittent fasting from dawn to sunset for 4 weeks is associated with an anticancer serum proteomic signature

This pilot study has important clinical implications, specifically from the standpoint of type of intermittent fasting on cancer prevention in subjects with metabolic syndrome. There are two major forms of daily intermittent fasting based on the time to start and end fasting: (1) Fasting that starts at dawn and ends at sunset (dusk). The fasting window is between two symmetrical transition time zones of the day (dawn and dusk) which is the human activity period (Fig. 1); (2) Fasting that starts at a self-determined time of the day and lasts for a fixed number of hours consisting of both human activity (daytime) and inactivity (nighttime) periods (e.g., 16:8 intermittent fasting that starts at 8 pm and ends at noon).

Ramadan fasting is a unique form of intermittent fasting from dawn to sunset (dusk) without eating or drinking during the month of Ramadan based on the lunar calendar16 and has several major unique features: (1) Fasting is exclusively practiced during the human activity hours from dawn to sunset (dusk) and is for both eating and drinking, which differentiates the dawn to sunset intermittent fasting from the other forms of intermittent fasting where drinking and/or eating light meals are allowed during the fasting window; (2) Although the main meals are at the transition time zones of the day (pre-dawn breakfast and dinner at sunset), eating (e.g., snacks) and drinking outside these transition time zones is allowed as long as it is within the non-fasting window; (3) There is no interventional calorie or energy restriction; (4) Daily fasting window is in synchrony with circadian rhythm and earth’s rotation on its axis because the daily fast starts at dawn (the first transition time zone of the day) after a pre-dawn breakfast and ends at sunset (dusk) (the second transition time zone of the day) with dinner; (5) Monthly fasting window is in synchrony with the moon’s rotation around the earth and lunar phases because the monthly fasting starts and ends when the new moon is sighted. It is surmised that this fasting pattern results in energy reserves being accessed without leading to micronutrient deficiencies due to replenishment after sunset.

Fasting during activity hours of the day appears to be of paramount importance in cancer prevention and treatment. A study showed that mice with no access to food during the activity phase of a 12-h light/12-h dark cycle had a significantly slower tumor progression and higher survival compared with mice that had no access to food during the inactivity phase, and mice that had access to food ad libitum13. The highest anticancer response occurred in the mice with no access to food during the activity phase, and the worse outcome was in the mice that had access to food ad libitum13. There was a minor anticancer effect and no survival benefit in the mice with no access to food during the inactivity phase13. In regards to humans, a study conducted among 2413 women with breast cancer without diabetes mellitus showed that fasting equal to or longer than 13 h at night (the combination of inactivity and activity hours) was associated with a reduced risk of breast cancer recurrence25. Of note, this study did not have control subjects who fasted exclusively during the activity hours (daytime)25. Altogether, these animal and human studies show that intermittent fasting either during daily activity or inactivity hours (with or without extending to activity hours) have an anticancer effect compared with ad libitum eating; however, the most robust anticancer response appears to occur when prolonged fasting is practiced exclusively during the activity hours13.

In accord with the findings of these murine and human studies13,25, we found a significant fold increase in the levels of specific tumor suppressor/anticancer proteins at the end of 4th week during 4-week intermittent fasting from dawn to sunset and/or 1 week after 4-week intermittent fasting from dawn to sunset, including CALR, CALU, INTS6, KIT, CROCC, PIGR, IGFBP4, and SEMA4B that are downregulated in several cancers resulting in cancer metastasis and poor prognosis (Table 2, Fig. 2). The CALR gene encodes for calreticulin, which is a calcium-binding protein located in the endoplasmic reticulum and nucleus26. Cancer cells tagged by calreticulin on their surface stimulate an immunogenic cancer cell death by enabling their phagocytosis by the dendritic cells of the immune system which in turn triggers T-cell-mediated immune response27,28,29. Obeid et al.28 showed that anthracyclines translocate calreticulin to the tumor cell surface, and trigger immunogenic tumor cell death (“eat me” signal).

CALU gene encodes for calumenin, a calcium-binding protein that plays a significant role in the endoplasmic reticulum functions, including folding and sorting of proteins26. Calumenin is an inhibitor of cell migration and metastasis in several cancers30, e.g., hepatocellular30,31, pancreatic30, head and neck squamous cell32, and lung squamous cell33 carcinomas. INTS6 gene encodes for a DEAD box RNA helicase that has a motif of Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp26. It is a tumor suppressor gene that plays a significant tumor-suppressive role in hepatocellular carcinoma and prostate ca34,35. The induction of INTS6 gene was shown to suppress castration-resistant prostate cancer35. Mutations in KIT are linked to several cancers26, and the loss of proto-oncogene c-KIT expression has been associated with poor prognosis in breast cancer36,37.

Several other anticancer GPs require elaboration. CROCC, also known as TAX1BP2, is a tumor-suppressor gene that was shown to suppress hepatocellular carcinoma via p38/p53/p21 pathway activation38. The downregulation of CROCC was associated with poor survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma after surgical resection38. PIGR, that encodes for polymeric immunoglobulin receptor26, was found to be downregulated in pancreatic39 and periampullary adenocarcinoma39 and lung cancer40. The upregulation of IGFBP4 (encodes for a protein that binds insulin-like growth factors I and II26), was shown to function as a potent tumor suppressor in hepatocellular carcinoma and delay tumor formation in prostate cancer cells41,42. SEMA4B is involved in protein-coding26 and encodes for a protein that inhibits tumor growth in non-small cell lung cancer43.

A significant fold-reduction in the levels of several tumor promoter/pro-cancer GPs was observed at the end of 4th week during 4-week intermittent fasting and/or 1 week after completion of 4-week intermittent fasting. These include POLK, NIFK, SRGN, CAMP, CD109, and PLAC1 that are upregulated in several cancers resulting in metastasis and poor prognosis (Table 2, Fig. 2).

POLK gene (POLQ) encodes for a specialized DNA polymerase26. Specialized DNA polymerases are ectopically overexpressed in several cancers, can function as an oncogene and enhance mutations induced by DNA damage44,45,46. Overexpression of POLK has been reported in lung cancer45,47. POLK overexpression contributes to cancer development by inactivating wild-type p53, and this was shown in lung cancer47. POLK gene also plays a role in breast cancer48. A case–control study showed a higher risk of developing breast cancer in women with two specific single nucleotide polymorphisms in the POLK gene compared with controls48. NIFK that encodes for a protein that functions in mitosis and progression of cell cycle26 was found to be upregulated and associated with poor prognosis in lung cancer49. SRGN encodes for a proteoglycan in hematopoietic cells26 and its overexpression is associated with poor prognosis in hepatocellular50, colorectal cancer51, non-small cell lung cancer52, and nasopharyngeal carcinoma53. CAMP that is also known as LL37 and CAP18, encodes for cathelicidin antimicrobial peptide26. CAMP was shown to increase the growth of colon cancer via Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway activation54 and function as a tumor promoter for lung55 and ovarian56 cancers. CD109 encodes for a glycosyl phosphatidylinositol-linked glycoprotein26 that was found to be overexpressed in several tumors, e.g., malignant melanoma57, squamous cell carcinoma of the lung58 and oral cavity59. PLAC1, which has a biased expression in placenta26, was shown to be expressed in hepatocellular carcinoma60, and overexpressed in breast cancer61, non-small cell lung cancer62, and pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma63.

Intermittent fasting from dawn to sunset for 4 weeks can play an important role in humoral defense against severe acute respiratory syndrome‐associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV)

Calreticulin was shown to enhance IgG-mediated immune response when it is fused with spike (S) protein of SARS-CoV64. Recombinant fusion protein that combines calreticulin and SARS-CoV S protein 450–650 fragment had much higher immunogenicity when compared with SARS-CoV S protein alone64. We found an average 16-fold increase in the CALR GP level 1 week after completion of 4-week intermittent fasting compared with the level before 4-week intermittent fasting. Our findings, combined with the prior report from Qiu et al.64, suggest that 4-week IF can play an important role in humoral defense against SARS-CoV, and further studies are needed.

Intermittent fasting from dawn to sunset for 4 weeks induces key regulatory proteins of insulin signaling and improves insulin resistance

Four-week intermittent fasting induced key regulatory proteins of insulin signaling, including VPS8, POLRMT and IGFBP5 at the end of 4th week during 4-week intermittent fasting and PRKCSH 1 week after 4-week intermittent fasting. The induction of VPS8, POLRMT, and IGFBP5 GPs at the end of 4th week during 4-week intermittent fasting preceded the significant reduction in insulin resistance estimated by HOMA-IR that occurred 1 week after 4-week intermittent fasting. VPS8, a subunit of CORVET complex26, plays a critical role in integrin requiring cell adhesion and migration, and recycling of beta-1 integrins65. Integrins are transmembrane receptors connecting the extracellular matrix to the actin cytoskeleton of the cells and thereby acting as a sensor for cell adhesion66. An impaired integrin signaling in the extracellular matrix of skeletal muscle, adipose tissue and liver can lead to insulin resistance67. An intact skeletal muscle and beta-cell mitochondrial function is vital for insulin synthesis. Type 2 diabetes mellitus is associated with skeletal muscle mitochondrial dysfunction and reduced oxidative capacity68. POLRMT encodes for the mitochondrial RNA polymerase26 that plays a critical role in transcription in pancreatic beta-cells and insulin secretion in the pancreas69. As the loss of POLRMT results in severe mitochondrial dysfunction in cardiac muscle70, a similar mitochondrial dysfunction should occur in beta-cells with the loss or dysfunction of POLRMT, resulting in insulin resistance and diabetes mellitus. IGFBP5 plays an active role in myoblast differentiation by binding to insulin growth factor II and upregulating its expression71. PRKCSH encodes for a protein called hepatocystin or 80K-H, which is a beta subunit of glucosidase II26 and substrate for protein kinase C26, that plays a key role in GLUT4 vesicle trafficking (translocation of GLUT4 to the plasma membrane) in the insulin signaling pathway 72 by forming a complex with 80K-H Overexpression of the hepatocystin 1 week after 4-week intermittent fasting is suggestive of improvement of insulin signaling through enhancement of GLUT4 vesicle trafficking. The upregulation of PRKCSH GPs coincided with the improvement in HOMA-IR 1 week after 4-week intermittent fasting.

Association of 4-week intermittent fasting from dawn to sunset with autophagy and oxidative stress parameters

Autophagy appears to be one of the mechanisms of intermittent fasting in cancer prevention73. Downregulation of the hepatocystin encoded by PRKCSH results in dysfunctional glucosidase II, and thereby increase in autophagy via mTOR dependent pathway74. The fact that we found reduction at the end of 4th week during 4-week intermittent fasting and then 73-fold increase in PRKCSH GP level 1 week after 4-week intermittent fasting is suggestive of increased autophagy during 4-week intermittent fasting and decreased autophagy with the subjects’ return to ad libitum eating (Table 2). Although it did not reach statistical significance, we found a reduction in multiple oxidative stress and inflammation biomarkers as well as gamma-glutamyl transferase levels, suggesting glutathione repletion at the end of 4th week during 4-week intermittent fasting (Table 1).

Intermittent fasting from dawn to sunset for 4 weeks upregulates proteins associated with prolonged longevity and DNA repair

We observed an average sixfold increase in H2B histone GP levels 1 week after 4-week intermittent fasting compared with the levels before 4-week intermittent fasting. Feser et al.75 demonstrated similar findings in yeast cells. They reported that histone proteins are lost in aging yeast cells, whereas histone protein overexpression and supplying extra histone proteins prolonged longevity75. Authors suggested that extra histone protein supply extends lifespan by providing a tighter chromatin packaging, and thereby restoring the transcriptional silencing that is lost in aging75. We also observed a significant positive correlation between H2B histone GP levels and high-density lipoprotein levels 1 week after 4-week intermittent fasting (Supplementary Table 5). The association between high-density lipoprotein levels and longevity was previously reported76. Our findings of a significant positive correlation between H2B histone GP and high-density lipoprotein levels 1 week after 4-week intermittent fasting shed light on the mechanistic understanding of the association between high-density lipoprotein levels and longevity. Besides the extended life span, the overexpression of histone proteins may also be associated with increased DNA expression and repair because irradiation-induced DNA damage was shown to downregulate histone gene transcription via the G1 checkpoint pathway77. Additionally, we observed an average 74-fold increase in the AP5Z1 GP level at the end of 4th week during 4-week intermittent fasting compared with the level before 4-week intermittent fasting. AP5Z1 is a helicase that likely plays a role in the repair of homologous recombination DNA double-strand break26. A variant in the AP5Z1 gene was associated with extreme longevity in a genome-wide association study conducted among 75,000 participants of the UK biobank78.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of our study are as follows: (1) We performed a robust, streamlined proteomics method to quantify proteins in the human serum using nano UHPLC-MS/MS15. With this unique proteomics method, we were able to recover more than 1000 GPs at the end of the 4th week during 4-week intermittent fasting (Fig. 2A) and 1 week after 4-week intermittent fasting (Fig. 2C); (2) We evaluated serum proteome simultaneously with the components of metabolic syndrome, lipid, and hepatic panels, and adiposity, oxidative stress, and inflammation biomarkers; (3) We assessed the carryover effect of 4-week intermittent fasting after switching to ad libitum eating. For this, we compared the GP levels measured 1 week after 4-week intermittent fasting with the levels measured at the end of 4th week during 4-week intermittent fasting. Several GPs that had a significant fold change at the end of 4th week during 4-week intermittent fasting compared with the levels before 4-week intermittent fasting, did not have any significant fold change 1 week after 4-week intermittent fasting compared with the levels at the end of 4th week during 4-week intermittent fasting (e.g., CALU, CAMP) (Table 2). These findings suggest that intermittent fasting has a carryover effect on these proteins. On the other hand, several GPs that had no significant fold change at the end of 4th week during 4-week intermittent fasting compared with the levels before 4-week intermittent fasting, had a significant fold change 1 week after 4-week intermittent fasting compared with the levels at the end of 4th week during 4-week intermittent fasting (e.g., PRKCSH, HIST1H2BA) (Table 2). These findings may suggest either decreased or delayed carryover effect of intermittent fasting on the proteome. There is also a possibility that intermittent fasting might have triggered a cascade of proteomic changes in a continuum that may not be explained by the assessment of the serum proteome at a single time point alone after intermittent fasting is stopped.

Several GPs that showed significant fold changes in subjects with metabolic syndrome had also shown similar changes (e.g., increase or decrease) at the end of 4th week during 30-day intermittent fasting (KIT, CROCC, DNTT, POLK, SRGN, CLSTN1) and 1 week after 30-day intermittent fasting (PRKCSH, CALU, SPECC1L, IGFBP4, MYH7, CDH6, H2B histone, PKP1, LRRC3, FGB, ENPP2) in our previous study conducted in healthy subjects although they had not reached statistical significance15.

The lack of caloric measurement by dietary assessment is one of the limitations of our study. The improvement in the components of metabolic syndrome could partially be explained by the significant weight reduction. Nonetheless, we did not find any significant correlation between log2 fold changes in the selected proteins (names are displayed in Table 2) and changes in weight, waist circumference and body mass index at the end of 4th week during 4-week intermittent fasting and 1 week after 4-week intermittent fasting compared with baseline suggesting that the effect of 4-week intermittent fasting from dawn to sunset on the proteomic changes was independent of weight reduction. Furthermore, our previous study conducted in healthy volunteers who fasted from dawn to sunset for 30 days showed the induction of an anticancer proteome in the absence of a significant weight change15. We estimated insulin resistance by HOMA-IR equation instead of performing an oral glucose tolerance test. A non-significant reduction in HOMA-IR at the end of 4th week during 4-week intermittent fasting might be related to insufficient accuracy of the HOMA-IR equation in our study population. HOMA-IR equation was found to have limited accuracy in adults between the ages 60 and 88 and subjects on insulin treatment (unless the glucose and insulin are in steady-state levels in subjects on insulin)79,80. Given the fact that 11 out of 14 study subjects were 60 years old or older and one subject was on insulin treatment, HOMA-IR might have underestimated the reduction in insulin resistance that occurred at the end of 4th week during 4-week intermittent fasting. Nonetheless, there was a reduction in glucose, insulin, and HOMA-IR levels at the end of 4th week during 4-week intermittent fasting. Although these findings did not reach statistical significance, they provide additional evidence for the antidiabetic effect of the 4-week intermittent fasting from dawn to sunset.

Conclusions

Serum proteomic signature of 4-week intermittent fasting from dawn to sunset for more than 14 h a day contributed to the mechanistic understanding of the effect of intermittent fasting from dawn to sunset on anticarcinogenesis, DNA repair, insulin signaling, humoral immunity and increased longevity in subjects with metabolic syndrome. Our findings suggest that intermittent fasting from dawn to sunset for four consecutive weeks, which is in synchrony with circadian rhythm and earth’s rotation can be an adjunct treatment in metabolic syndrome and should be tested in the prevention and treatment of metabolic syndrome-induced cancers. Altogether, our findings are in line with the results of our earlier study of 30-day dawn to sunset intermittent fasting conducted in healthy subjects15 and lay the foundation data for a randomized, controlled clinical trial of dawn to sunset intermittent fasting in subjects with metabolic syndrome.

References

Moore, J. X., Chaudhary, N. & Akinyemiju, T. Metabolic syndrome prevalence by race/ethnicity and sex in the United States, National Health And Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–2012. Prev. Chronic Dis. 14, E24. https://doi.org/10.5888/Pcd14.160287 (2017).

Grundy, S. M. et al. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: An American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung. And Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation 112, 2735–2752. https://doi.org/10.1161/Circulationaha.105.169404 (2005).

Afshin, A. et al. Health effects of overweight and obesity in 195 countries over 25 years. N. Engl. J. Med. 377, 13–27. https://doi.org/10.1056/Nejmoa1614362 (2017).

Esposito, K., Chiodini, P., Colao, A., Lenzi, A. & Giugliano, D. Metabolic syndrome and risk of cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 35, 2402–2411. https://doi.org/10.2337/Dc12-0336 (2012).

Welzel, T. M. et al. Metabolic syndrome increases the risk of primary liver cancer in the United States: A study in the seer-medicare database. Hepatology 54, 463–471. https://doi.org/10.1002/Hep.24397 (2011).

Greene, M. W. Circadian rhythms and tumor growth. Cancer Lett. 318, 115–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.Canlet.2012.01.001 (2012).

Shetty, A., Hsu, J. W., Manka, P. P. & Syn, W.-K. Role of the circadian clock in the metabolic syndrome and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Dig. Dis. Sci. 63, 3187–3206. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10620-018-5242-X (2018).

Kettner, N. M. et al. Circadian homeostasis of liver metabolism suppresses hepatocarcinogenesis. Cancer Cell 30, 909–924. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.Ccell.2016.10.007 (2016).

Russo, A., Autelitano, M. & Bisanti, L. Metabolic syndrome and cancer risk. Eur. J. Cancer 44, 293–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.Ejca.2007.11.005 (2008).

Li, X.-M. et al. Cancer inhibition through circadian reprogramming of tumor transcriptome with meal timing. Can. Res. 70, 3351–3360. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.Can-09-4235 (2010).

Hatori, M. et al. Time-restricted feeding without reducing caloric intake prevents metabolic diseases in mice fed a high-fat diet. Cell Metab. 15, 848–860. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.Cmet.2012.04.019 (2012).

Harvie, M. N. & Howell, T. Could intermittent energy restriction and intermittent fasting reduce rates of cancer in obese, overweight, and normal-weight subjects? A summary of evidence. Adv. Nutr. 7, 690–705. https://doi.org/10.3945/An.115.011767 (2016).

Wu, M. W., Li, X. M., Xian, L. J. & Levi, F. Effects of meal timing on tumor progression in mice. Life Sci. 75, 1181–1193. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.Lfs.2004.02.014 (2004).

Damiola, F. et al. Restricted feeding uncouples circadian oscillators in peripheral tissues from the central pacemaker in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Genes Dev. 14, 2950–2961 (2000).

Mindikoglu, A. L. et al. Intermittent fasting from dawn to sunset for 30 consecutive days is associated with anticancer proteomic signature and upregulates key regulatory proteins of glucose and lipid metabolism, circadian clock, dna repair, cytoskeleton remodeling, immune system and cognitive function in healthy subjects. J. Proteom. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.Jprot.2020.103645 (2020).

Mindikoglu, A. L., Opekun, A. R., Gagan, S. K. & Devaraj, S. Impact of time-restricted feeding and dawn-to-sunset fasting on circadian rhythm, obesity, metabolic syndrome, and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterol. Res. Pract. 2017, 3932491. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/3932491 (2017).

Sadiya, A., Ahmed, S., Siddieg, H. H., Babas, I. J. & Carlsson, M. Effect of ramadan fasting on metabolic markers, body composition, and dietary intake in Emiratis of Ajman (Uae) with metabolic syndrome. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. Targets Ther. 4, 409–416. https://doi.org/10.2147/Dmso.S24221 (2011).

Shariatpanahi, Z. V., Shariatpanahi, M. V., Shahbazi, S., Hossaini, A. & Abadi, A. Effect of ramadan fasting on some indices of insulin resistance and components of the metabolic syndrome in healthy male adults. Br. J. Nutr. 100, 147–151. https://doi.org/10.1017/S000711450787231x (2008).

Wilkinson, M. J. et al. Ten-hour time-restricted eating reduces weight, blood pressure, and atherogenic lipids in patients with metabolic syndrome. Cell Metab. 31, 92–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.Cmet.2019.11.004 (2020).

Fibroscan. https://Echosens.Us/. Accessed 19 Feb 2020.

Opekun, A. R., Balesh, A. M. & Shelby, H. T. Use of the biphasic (13)C-sucrose/glucose breath test to assess sucrose maldigestion in adults with functional bowel disorders. Biomed. Res. Int. 2016, 7952891. https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/7952891 (2016).

Matthews, D. R. et al. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and Β-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 28, 412–419. https://doi.org/10.1007/Bf00280883 (1985).

Madhavan, S., Ooi, W. L., Cohen, H. & Alderman, M. H. Relation of pulse pressure and blood pressure reduction to the incidence of myocardial infarction. Hypertension 23, 395–401. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.Hyp.23.3.395 (1994).

Sas Software. https://www.Sas.com/. The Data Analysis for this Paper Was Generated Using Sas Software, Version 9.4 of the Sas System For Windows. Copyright 2016 Sas Institute Inc. Sas And All Other Sas Institute Inc. Product or Service Names Are Registered Trademarks or Trademarks of Sas Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA.

Marinac, C. R. et al. Prolonged nightly fasting and breast cancer prognosis. JAMA Oncol. 2, 1049–1055. https://doi.org/10.1001/Jamaoncol.2016.0164 (2016).

Gene [Internet]. Bethesda (Md): National Library Of Medicine (Us), National Center For Biotechnology Information; 2004—[Cited 2019 Nov 17]. https://www.Ncbi.Nlm.Nih.Gov/Gene/.

Wang, W.-A., Groenendyk, J. & Michalak, M. Calreticulin signaling in health and disease. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 44, 842–846. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.Biocel.2012.02.009 (2012).

Obeid, M. et al. Calreticulin exposure dictates the immunogenicity of cancer cell death. Nat. Med. 13, 54–61. https://doi.org/10.1038/Nm1523 (2007).

Clarke, C. & Smyth, M. J. Calreticulin exposure increases cancer immunogenicity. Nat. Biotechnol. 25, 192–193. https://doi.org/10.1038/Nbt0207-192 (2007).

Wang, Q. et al. Extracellular calumenin suppresses Erk1/2 signaling and cell migration by protecting fibulin-1 from Mmp-13-mediated proteolysis. Oncogene 34, 1006–1018. https://doi.org/10.1038/Onc.2014.52 (2015).

Ding, S. J. et al. Proteome analysis of hepatocellular carcinoma cell strains, Mhcc97-H And Mhcc97-L, with different metastasis potentials. Proteomics 4, 982–994. https://doi.org/10.1002/Pmic.200300653 (2004).

Wu, W. et al. Identification and validation of metastasis-associated proteins in head and neck cancer cell lines by two-dimensional electrophoresis and mass spectrometry. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 19, 319–326, https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1015515119300 (2002).

Shen, C. et al. Molecular cloning, identification and analysis of lung squamous cell carcinoma-related genes. Lung Cancer 38, 235–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0169-5002(02)00300-8 (2002).

Peng, H. et al. Pseudogene Ints6p1 regulates its cognate gene Ints6 through competitive binding of Mir-17-5p in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget 6, 5666–5677. https://doi.org/10.18632/Oncotarget.3290 (2015).

Chen, H. et al. Small RNA-induced Ints6 gene up-regulation suppresses castration-resistant prostate cancer cells by regulating Β-catenin signaling. Cell Cycle 17, 1602–1613. https://doi.org/10.1080/15384101.2018.1475825 (2018).

Natali, P. G. et al. Breast cancer is associated with loss of the C-Kit oncogene product. Int. J. Cancer 52, 713–717. https://doi.org/10.1002/Ijc.2910520508 (1992).

Janostiak, R., Vyas, M., Cicek, A. F., Wajapeyee, N. & Harigopal, M. Loss of C-Kit expression in breast cancer correlates with malignant transformation of breast epithelium and is mediated by kit gene promoter DNA hypermethylation. Exp. Mol. Pathol. 105, 41–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.Yexmp.2018.05.011 (2018).

Lai, W.-L. et al. The centrosomal protein Tax1 binding protein 2 is a novel tumor suppressor in hepatocellular carcinoma regulated by cyclin-dependent kinase 2. Hepatology 56, 1770–1781. https://doi.org/10.1002/Hep.25851 (2012).

Fristedt, R. et al. Reduced expression of the polymeric immunoglobulin receptor in pancreatic and periampullary adenocarcinoma signifies tumour progression and poor prognosis. PLoS ONE 9, E112728. https://doi.org/10.1371/Journal.Pone.0112728 (2014).

Ocak, S. et al. Loss of polymeric immunoglobulin receptor expression is associated with lung tumourigenesis. Eur. Respir. J. 39, 1171–1180. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00184410 (2012).

Lee, Y.-Y. et al. Loss of tumor suppressor Igfbp4 drives epigenetic reprogramming in hepatic carcinogenesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, 8832–8847. https://doi.org/10.1093/Nar/Gky589 (2018).

Damon, S. E., Maddison, L., Ware, J. L. & Plymate, S. R. Overexpression of an inhibitory insulin-like growth factor binding protein (Igfbp), Igfbp-4, delays onset of prostate tumor formation*. Endocrinology 139, 3456–3464. https://doi.org/10.1210/Endo.139.8.6150 (1998).

Jian, H., Zhao, Y., Liu, B. & Lu, S. Sema4b inhibits growth of non-small cell lung cancer in vitro and in vivo. Cell. Signal. 27, 1208–1213. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.Cellsig.2015.02.027 (2015).

Albertella, M. R., Lau, A. & O’connor, M. J. The overexpression of specialized DNA polymerases in cancer. DNA Repair 4, 583–593. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.Dnarep.2005.01.005 (2005).

O-Wang, J. et al. DNA polymerase Κ, implicated in spontaneous and DNA damage-induced mutagenesis, is overexpressed in lung cancer. Cancer Res. 61, 5366–5369 (2001).

Lehmann, A. R. Replication of UV-damaged DNA: New insights into links between DNA polymerases, mutagenesis and human disease. Gene 253, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1119(00)00250-X (2000).

Wang, Y. et al. Elevated expression of DNA polymerase kappa in human lung cancer is associated with P53 inactivation: Negative regulation of polk promoter activity By P53. Int. J. Oncol. 25, 161–165 (2004).

Dai, Z. J. et al. Association between single nucleotide polymorphisms in DNA polymerase kappa gene and breast cancer risk in Chinese han population: A strobe-compliant observational study. Medicine (Baltimore) 95, E2466. https://doi.org/10.1097/Md.0000000000002466 (2016).

Lin, T.-C. et al. The nucleolar protein NIFK promotes cancer progression via CK1α/β-catenin in metastasis and Ki-67-dependent cell proliferation. Elife 5, e11288, https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.11288 (2016).

He, L. et al. Serglycin (Srgn) overexpression predicts poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Med. Oncol. 30, 707. https://doi.org/10.1007/S12032-013-0707-4 (2013).

Xu, Y. et al. Srgn promotes colorectal cancer metastasis as a critical downstream target of Hif-1alpha. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 48, 2429–2440. https://doi.org/10.1159/000492657 (2018).

Guo, J. Y. et al. Serglycin in tumor microenvironment promotes non-small cell lung cancer aggressiveness in a Cd44-dependent manner. Oncogene 36, 2457–2471. https://doi.org/10.1038/Onc.2016.404 (2017).

Li, X.-J. et al. Serglycin is a theranostic target in nasopharyngeal carcinoma that promotes metastasis. Can. Res. 71, 3162–3172. https://doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.Can-10-3557 (2011).

Li, D. et al. Cathelicidin, an antimicrobial peptide produced by macrophages, promotes colon cancer by activating the Wnt/Β-catenin pathway. Oncotarget 6, 2939–2950. https://doi.org/10.18632/Oncotarget.2845 (2015).

Von Haussen, J. et al. The host defence peptide Ll-37/Hcap-18 is a growth factor for lung cancer cells. Lung Cancer 59, 12–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.Lungcan.2007.07.014 (2008).

Coffelt, S. B. et al. Ovarian cancers overexpress the antimicrobial protein Hcap-18 and its derivative Ll-37 increases ovarian cancer cell proliferation and invasion. Int. J. Cancer 122, 1030–1039. https://doi.org/10.1002/Ijc.23186 (2008).

Ohshima, Y. et al. Cd109 expression levels in malignant melanoma. J. Dermatol. Sci. 57, 140–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.Jdermsci.2009.11.004 (2010).

Sato, T. et al. High-level expression of Cd109 is frequently detected in lung squamous cell carcinomas. Pathol. Int. 57, 719–724. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1440-1827.2007.02168.X (2007).

Hagiwara, S. et al. Up-regulation of Cd109 expression is associated with carcinogenesis of the squamous epithelium of the oral cavity. Cancer Sci. 99, 1916–1923. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1349-7006.2008.00949.X (2008).

Guo, L., Xu, D., Lu, Y., Peng, J. & Jiang, L. Detection of circulating tumor cells by reverse transcriptionquantitative polymerase chain reaction and magnetic activated cell sorting in the peripheral blood of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol. Med. Rep. 16, 5894–5900. https://doi.org/10.3892/Mmr.2017.7372 (2017).

Li, Y. et al. Cancer/testis antigen-Plac1 promotes invasion and metastasis of breast cancer through Furin/Nicd/Pten signaling pathway. Mol. Oncol. 12, 1233–1248. https://doi.org/10.1002/1878-0261.12311 (2018).

Yang, L. et al. Placenta-specific protein 1 promotes cell proliferation and invasion in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol. Rep. 39, 53–60. https://doi.org/10.3892/Or.2017.6086 (2018).

Yin, Y. et al. Expression and clinical significance of placenta-specific 1 in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Tumor Biol. 39, 1010428317699131. https://doi.org/10.1177/1010428317699131 (2017).

Qiu, X., Hong, C., Li, Y., Bao, W. & Gao, X.-M. Calreticulin as a hydrophilic chimeric molecular adjuvant enhances Igg responses to the spike protein of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Microbiol. Immunol. 56, 554–561. https://doi.org/10.1111/J.1348-0421.2012.00467.X (2012).

Jonker, C. T. H. et al. Vps3 And Vps8 control integrin trafficking from early to recycling endosomes and regulate integrin-dependent functions. Nat. Commun. 9, 792. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41467-018-03226-8 (2018).

Hynes, R. O. Integrins: Bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell 110, 673–687. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00971-6 (2002).

Williams, A. S., Kang, L. & Wasserman, D. H. The extracellular matrix and insulin resistance. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 26, 357–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.Tem.2015.05.006 (2015).

Phielix, E. & Mensink, M. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and skeletal muscle metabolic function. Physiol. Behav. 94, 252–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.Physbeh.2008.01.020 (2008).

Mulder, H. Transcribing Β-cell mitochondria in health and disease. Mol. Metab. 6, 1040–1051. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.Molmet.2017.05.014 (2017).

Kühl, I. et al. Polrmt regulates the switch between replication primer formation and gene expression of mammalian Mtdna. Sci. Adv. 2, E1600963. https://doi.org/10.1126/Sciadv.1600963 (2016).

Ren, H., Yin, P. & Duan, C. Igfbp-5 regulates muscle cell differentiation by binding to Igf-Ii and switching on the Igf-Ii auto-regulation loop. J. Cell Biol. 182, 979–991. https://doi.org/10.1083/Jcb.200712110 (2008).

Hodgkinson, C. P., Mander, A. & Sale, G. J. Identification of 80k-H as a protein involved in Glut4 vesicle trafficking. Biochem. J. 388, 785–793. https://doi.org/10.1042/Bj20041845 (2005).

Antunes, F. et al. Autophagy and intermittent fasting: The connection for cancer therapy?. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 73, E814s–E814s. https://doi.org/10.6061/Clinics/2018/E814s (2018).

Yang, J. et al. Deficiency of hepatocystin induces autophagy through an Mtor-dependent pathway. Autophagy 7, 748–759. https://doi.org/10.4161/Auto.7.7.15822 (2011).

Feser, J. et al. Elevated histone expression promotes life span extension. Mol. Cell 39, 724–735. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.Molcel.2010.08.015 (2010).

Milman, S., Atzmon, G., Crandall, J. & Barzilai, N. Phenotypes and genotypes of high density lipoprotein cholesterol in exceptional longevity. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 12, 690–697. https://doi.org/10.2174/1570161111666131219101551 (2014).

Su, C. et al. Dna damage induces downregulation of histone gene expression through the G1 checkpoint pathway. EMBO J. 23, 1133–1143. https://doi.org/10.1038/Sj.Emboj.7600120 (2004).

Pilling, L. C. et al. Human longevity is influenced by many genetic variants: Evidence from 75,000 UK Biobank participants. Aging (Albany NY) 8, 547–560. https://doi.org/10.18632/Aging.100930 (2016).

Chang, A. M. et al. Limitation of the homeostasis model assessment to predict insulin resistance and beta-cell dysfunction in older people. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 91, 629–634. https://doi.org/10.1210/Jc.2005-1803 (2006).

Wallace, T. M., Levy, J. C. & Matthews, D. R. Use and abuse of homa modeling. Diabetes Care 27, 1487–1495. https://doi.org/10.2337/Diacare.27.6.1487 (2004).

Acknowledgements

Authors thank Scott C Holmes, C.M.I., a member of the Michael E. DeBakey Department of Surgery Research Core at Baylor College of Medicine, for his assistance during the preparation of Fig. 1.

Funding

This project was supported by 2019 Roderick D. MacDonald Research Award/Baylor St. Luke’s Medical Center (Award Number 19RDM001) (to Ayse L. Mindikoglu, M.D., M.P.H.). This project was supported in part by NIH Public Health Service grant P30DK056338, which funds the Texas Medical Center Digestive Diseases Center and P30CA125123, which funds the Baylor College of Medicine (BCM) Proteomics Core and its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Cancer Institute or the NIH. This project was supported in part by Gladys and David Laws Fund.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.L.M. formulated the study hypothesis and study concept, designed the study, drafted the manuscript, contributed with conducting the study, analyzing data, and critically reviewing and finalizing the manuscript. M.M.A. contributed with conducting the study, and critically reviewing the manuscript. A.J. contributed with performing serum proteomic analysis and critically reviewing the manuscript. P.K.J. contributed with conducting the study, and critically reviewing the manuscript. S.D. contributed with performing the analysis of components of metabolic syndrome, lipid and hepatic panels, and adiposity, oxidative stress and inflammation biomarkers and critically reviewing the manuscript. Z.R.W. contributed with conducting the study and critically reviewing the manuscript. A.R.O. contributed with conducting the study, and critically reviewing the manuscript. S.Y.J. contributed with performing serum proteomic analysis, analyzing data, and critically reviewing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mindikoglu, A.L., Abdulsada, M.M., Jain, A. et al. Intermittent fasting from dawn to sunset for four consecutive weeks induces anticancer serum proteome response and improves metabolic syndrome. Sci Rep 10, 18341 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-73767-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-73767-w

This article is cited by

-

Systemic proteome adaptions to 7-day complete caloric restriction in humans

Nature Metabolism (2024)

-

Intramuscular mitochondrial and lipid metabolic changes of rats after regular high-intensity interval training (HIIT) of different training periods

Molecular Biology Reports (2023)

-

Peristalsis-Associated Mechanotransduction Drives Malignant Progression of Colorectal Cancer

Cellular and Molecular Bioengineering (2023)

-

The CUN-BAE, Deurenberg Fat Mass, and visceral adiposity index as confident anthropometric indices for early detection of metabolic syndrome components in adults

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Body mass index–based predictions and personalized clinical strategies for colorectal cancer in the context of PPPM

EPMA Journal (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.