Abstract

Raffinose family oligosaccharides (RFOs) are implicated in plant regulatory mechanisms of abiotic stresses tolerance and, despite their antinutritional proprieties in grain legumes, little information is available about the enzymes involved in RFO metabolism in Fabaceae species. In the present study, the systematic survey of legume proteins belonging to five key enzymes involved in the metabolism of RFOs (galactinol synthase, raffinose synthase, stachyose synthase, alpha-galactosidase, and beta-fructofuranosidase) identified 28 coding-genes in Arachis duranensis and 31 in A. ipaënsis. Their phylogenetic relationships, gene structures, protein domains, and chromosome distribution patterns were also determined. Based on the expression profiling of these genes under water deficit treatments, a galactinol synthase candidate gene (AdGolS3) was identified in A. duranensis. Transgenic Arabidopsis plants overexpressing AdGolS3 exhibited increased levels of raffinose and reduced stress symptoms under drought, osmotic, and salt stresses. Metabolite and expression profiling suggested that AdGolS3 overexpression was associated with fewer metabolic perturbations under drought stress, together with better protection against oxidative damage. Overall, this study enabled the identification of a promising GolS candidate gene for metabolic engineering of sugars to improve abiotic stress tolerance in crops, whilst also contributing to the understanding of RFO metabolism in legume species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Persistent abiotic stress conditions, such as drought, salinity and extreme temperatures, are major environmental adverse factors that negatively affect the physiology and biochemistry of plants and limit crop production worldwide. To withstand the damaging effects of the intracellular water loss caused by the different types of abiotic stresses, plants have evolved a molecular arsenal for stress sensing, signaling, acclimation, and defense1. Complex molecular networks are thus activated to allow plants to cope with stressful conditions2, including modifications in plant metabolism to produce a series of low molecular weight compounds that accumulate in the cytosol or vacuole, such as soluble sugars, amines and amino acids3. These compounds participate in osmotic adjustment, stabilize cell components, provide membrane protection, and scavenge excess Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)4.

The raffinose family oligosaccharides (RFOs), such as raffinose, stachyose and verbascose, have been intensively studied as osmoprotectants that accumulate in response to abiotic stress, representing a crucial element of plant defense mechanisms3,5. These oligosaccharides also have many other functions in plants, including protection of the embryo during maturation and desiccation of seeds, long-distance sugar transport in the phloem sap, storage of carbon, protection of the photosynthetic apparatus, mRNA export, and as signaling molecules in plant defense upon wounding or pathogen infection.

Biosynthesis of RFOs begins with the conversion of uridine diphosphate-galactose (UDP-Gal) and myo-inositol to galactinol catalyzed by galactinol synthase (GolS)6. GolS has a significant influence over RFO accumulation, as the first enzyme that commits carbon to RFO biosynthesis, and hence influences carbon partitioning between sucrose and RFOs. Raffinose, the first member of this series of RFOs, is synthesized by raffinose synthase (RS) through the transfer of a galactosyl moiety from galactinol to sucrose. The subsequent addition of another galactosyl residue to raffinose by stachyose synthase (STS) results in the production of stachyose7. Raffinose and stachyose can then be cleaved to produce a number of different oligosaccharides. The removal of the fructosyl unit of raffinose and stachyose by beta-fructofuranosidase (BFLUCT) leads to the formation of melibiose and manninotriose, respectively. Galactose can also be removed from RFOs through the action of alpha-galactosidase (AGAL).

Galactinol and RFOs are ubiquitous in plants and the genes coding for enzymes involved in their metabolism have been identified and characterized in some crop species, including Zea mays8, Manihot esculenta9, Sesamum indicum10, Solanum lycopersicum11 and Malus × domestica12. Whilst RFOs are major soluble sugars that are second only to sucrose in abundance in mature legume seeds13, very little is known about the genes involved in raffinose metabolism in Fabaceae species, with few examples described in Cicer arietinum and Glycine max14,15. RFOs are indeed antinutritional and undesirable compounds of legume seeds and the development of cultivars with reduced levels of raffinose and stachyose has been the focus of breeding programs for improving nutritional quality in many grain legumes13,16,17. In peanut (Arachis hypogaea), the second most cultivated grain legume in the world after soybean, seeds also accumulate high amounts of indigestible RFOs, which limits its consumption13,17.

Over the past years, we have exploited the peanut wild relatives gene pool as a source of valuable traits for peanut breeding, such as resistance/tolerance to abiotic and biotic stresses18. Progress in functional genomics of wild Arachis led to the discovery of many genes and proteins involved in water deficit responses in the drought-tolerant A. duranensis and in the drought-sensitive A. stenosperma, including genes involved in RFO metabolism19,20,21,22,23,24. Furthermore, the availability of the complete genome sequences of the wild ancestral species of peanut, A. duranensis and A. ipaënsis (https://www.peanutbase.org/), has enabled genome-wide analysis and contributed to new insights into the molecular function and evolution of gene families in the genus Arachis25. However, despite the important role of peanut, and other legumes, as protein sources for human and animal consumption, a detailed study of the genomic organization of RFO metabolic genes is still missing.

In the present study, a genome-wide analysis identified 28 genes in A. duranensis and 31 in A. ipaënsis as coding for five key enzymes of the RFO biosynthesis, accumulation, and catabolism (GolS, RS, STS, AGAL and BFLUCT). Phylogenetic relationships, gene and protein structures, and the chromosome distribution patterns of these genes were also characterized. Additionally, analysis of transcriptome data of different wild Arachis species submitted to water deficit treatments identified the AdGolS3 gene as a candidate gene for drought tolerance. The effects of AdGolS3 overexpression in transgenic Arabidopsis plants and its putative role in abiotic stress responses were investigated. Our findings indicated AdGolS3 may act preventively to protect plant cells against oxidative damage and therefore contribute to drought tolerance.

Methods

Construction of profile hidden Markov models and scans of Fabaceae predicted proteomes

The protein sequences of five key enzymes involved in plant raffinose metabolism were downloaded from Carbohydrate-Active enZyme database (CAZy; https://www.cazy.org/;26). In CAZy, only the proteins whose biochemical activity has been experimentally confirmed are assigned an Enzyme Commission (EC) number. We thus retrieved from legumes the glycosyltransferase family 8 (GT8) galactinol synthase (GolS; EC 2.4.1.123) and the glycoside hydrolases: family 36 (GH36) raffinose synthase (RS; EC 2.4.1.82) and stachyose synthase (STS; EC 2.4.1.67); family 27 (GH27) alpha-galactosidase (AGAL; EC 3.2.1.22); and family 32 (GH32) beta-fructofuranosidase (BFLUCT; EC 3.2.1.26). For each selected CAZyme family, protein sequences found in Fabaceae species were aligned using MAFFT software27 and trimmed with trimAL software, to eliminate regions with more than 10% gaps28. For each of the five enzymes, a profile hidden Markov model (profile-HMM) was built using the hmmbuild function from HMMER suite v3.1 (https://hmmer.org/;29), with the aligned and trimmed protein sequences as input.

The predicted proteomes of A. duranensis and A. ipaënsis25 were retrieved from PeanutBase (https://peanutbase.org/) and the protein sets of the remaining Fabaceae species were downloaded from the UniProt database (https://www.uniprot.org/taxonomy/fabaceae/). The five HMM profiles (for GolS; RS; STS; AGAL and BFLUCT) were then used as queries against this set of proteomes to find the matching proteins, using the hmmsearch function from HMMER v3.1 (https://hmmer.org/). Only the protein sequences with a full sequence score > 100 were retained and considered for further analyses. The CD-HIT software (https://weizhongli-lab.org/cd-hit/;30) was used to eliminate the redundant proteins, with a cut-off sequence identity of 90%. Details of the methods used for final multiple sequence alignments and phylogenetic analysis as well as the analysis of gene/protein structures and genomic distribution in Arachis spp. are given in the Supplementary Methods.

In silico expression profiling of A. duranensis genes

Illumina RNA-seq data previously obtained by our group were used to determine the in silico expression profiles of GolS, RS, STS, AGAL and BFLUCT genes in Arachis spp. This data comprises: (1) Transcripts expressed in roots of A. duranensis and A. stenosperma plants submitted to dehydration treatment, by the withdrawal of hydroponic nutrient solution from 25 to 150 min21 and pooled in equal amounts, a treatment which we previously showed to induce major alterations in the transcriptome of these species. (2) Transcripts expressed in A. duranensis and A. stenosperma plants subjected to a decreased in soil availability with withholding of irrigation for four days, a treatment which induced proteomic and transcriptomic alterations24. The differential expression values (log2 of fold-change) between stressed and control samples in A. duranensis and A. stenosperma roots were plotted in a heatmap graph using the heatmap2 from ggplot R package, as previously described23.

Arabidopsis thaliana lines overexpressing AdGolS3 gene

The coding sequence of the AdGolS3 gene was identified by the alignment of the Aradu.ZK8VV gene model (https://peanutbase.org) with the four best BLASTn hits of A. duranensis at NCBI (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). The obtained AdGolS3 consensus sequence (981 bp) was synthetized and cloned under the control of the A. thaliana actin 2 promoter in the binary vector pPZP_201BK_EGFP31 by Epoch Life Science Inc. (TX, USA). The resulting vector, pPZP-AdGolS3, was transferred to the Agrobacterium disarmed strain ‘GV3101’ and the transformed colonies selected by PCR with specific eGFP and AdGolS3 primers (Table S1), using standard protocols.

Wild-type (WT) A. thaliana plants (ecotype Columbia; Col-0) were transformed with the GV3101-pPZP-AdGolS3 Agrobacterium strain by the floral dip immersion method32. The eGFP-positive and hygromycin-resistant T0 transformants were grown in a controlled growth chamber (21 °C with a 12 h photoperiod and light intensity of 120 µmols.m−2.s−1) to obtain transgenic AdGolS3 overexpressing (OE) lines, as described previously22. T1 seeds of each transgenic line obtained by self-pollination of T0 plants were germinated on hygromycin selective medium and T1 plants grown to maturity. Self-pollinated T2 seeds derived from each T1 plant were maintained separate and 24 T2 seeds tested for homozygosity through germination on hygromycin selective medium. If all T2 seeds germinated in hygromycin selective medium, we considered that they derived from a T1 plant homozygote producing T2 homozygous seeds. All the subsequent stress treatments and analyses were conducted with homozygous AdGolS3-OE plants of the T2 generation.

Transgene expression and sugar content in AdGolS3-OE lines

The expression of AdGolS3 transgene in 13 independent Arabidopsis OE lines was confirmed through qRT-PCR analysis as described below (2.10), using specific AdGolS3 primers (Table S1). The content of four sugars (glucose, fructose, sucrose and raffinose) was determined in leaves of one-month-old WT and transgenic plants (five individuals per genotype) as described previously33. Sugars were extracted using 80% (v/v) ethanol at 80 °C, and the extracts dried and resuspended in water for analysis. Samples were analyzed using a High Performance Anion Exchange (HPAE) chromatography system (Dionex, ICS 3,000, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) equipped with a pulsed amperometric detector and Carbopak PA-10 column. Sugars were separated using an isocratic method with 52 mM NaOH and a column flow of 0.2 mL.min−1 over 35 min and quantified using standard curves.

Dry-down assay

Based on the HPAE analysis, three AdGolS3-OE lines (GolS17, GolS20 and GolS22) that showed significantly higher levels of raffinose compared to WT were selected for the subsequent abiotic stress assays. Seeds from WT and transgenic plants were sown in 250 mL pots containing the same amount of substrate (Carolina Soil, CSC, Brazil) and maintained under the growth conditions described above. The dry-down assay started when the plants were 30 days old and lasted for 20 days. Plants were divided into three treatments: (1) Control (CTR) group maintained under irrigated conditions, i.e., around 70% of field capacity (FC); (2) Stressed (STR) group where irrigation was suspended; and (3) Rehydrated (REH) group where STR plants were irrigated 24 h before collection. CTR, STR and REH treatments started at the same time and were carried out in parallel, each group with its own set of plants. At the end of the assay, ten individuals from each treatment (CTR, STR and REH) were collected (at 9 am) for each genotype, weighed and stored at -80 °C for later biochemical and molecular analyses.

The leaf disc submersion methods were used for the determination of the relative water content (RWC) and electrolyte leakage (EL), as described previously34,35. For RWC and EL measurements, three leaf discs of 0.4 cm2 were used per individual for each treatment (CTR, STR and REH).

Soluble sugar analysis and metabolic profiling

Soluble sugars (glucose, sucrose and raffinose) were separated and quantified in the three selected AdGolS3-OE lines and in WT plants under CTR, STR and REH conditions using the HPAE chromatography system, as described above. Metabolic profiling of these four genotypes was carried out according to36. Samples of lyophilized tissue were extracted using the methanol:chloroform:water method with ribitol as an internal standard. Aliquots of the polar phase were dried and derivatized using methyoxyamine hydrochloride in pyridine followed by MSTFA. Samples were analyzed using an Agilent 7820A GC coupled to an Agilent 5,975 MSD equipped with a 30 m HP5-ms column. Metabolites were identified by comparison with a custom mass spectral library and chromatograms were aligned using MetaAlign37.

NaCl and PEG treatments

Based on the results of the dry-down experiment, the GolS22 OE line was selected for evaluation of its performance in response to two additional abiotic stress treatments: NaCl (salt stress) and polyethylene glycol (PEG; osmotic stress). WT and GolS22 plants were grown as described above for 30 days then divided between three groups: (1) Control group maintained under irrigated conditions (maintained at 70% FC); (2) Salt stressed group irrigated with a 150 mM NaCl solution instead of water; and (3) Osmotic stressed group irrigated with a PEG 6,000 20% (w/v) solution instead of water. Plants from each group were maintained under these conditions for 15 days. Ten individuals from each treatment were collected (at 9 am) per genotype, weighed and analyzed for RWC and EL, as described above.

qRT-PCR analysis

The relative expression of the AdGolS3 transgene and of a subset of Arabidopsis genes was determined in WT plants and OE lines by qRT-PCR analysis, as previously described22. This gene subset comprises five Arabidopsis genes selected based on their putative interaction with AtGolS2 in Arabidopsis, as predicted by geneMANIA38. It includes (Table S1): Glutathione S-transferase (AtGSTU24), Stress‐Associated Protein (AtSAP13), Ascorbate Peroxidase (AtAPX1), Peroxisomal Catalase (AtCAT2) and Alpha amylase family protein (AtEMB2729). AtGolS2 is the orthologous of the AdGolS3 gene in Arabidopsis and was included in the qRT-PCR analysis. Specific primers were designed (Table S1) using the software Primer3Plus, following the parameters described previously39. The qRT-PCR reactions were performed on a StepOne Plus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, USA) in technical triplicates for each sample, using No Template (NTC) and No Amplification (NAC) samples as negative controls. The relative quantification (RQ) of mRNA levels was normalized with AtACT2 and AtEF-1α reference genes (Table S1).

Results

Genome-wide identification of wild Arachis genes involved in RFO metabolism

Galactinol synthase (GolS)

We identified six plant proteins with experimentally verified biochemical function in the CAZy database as GolS proteins that shared the common conserved PFAM domain (PF01501) of the GT8 family. The two belonging to the Fabaceae family (GLYMA Q7XZ08 and MEDSA Q84MZ5) were then used as references for HMM profile construction.

Using this HMM profile, 30 proteins from 11 Fabaceae species were identified in UniProt as putatively belonging to the GolS family (Table S2), together with five proteins each for A. duranensis and A. ipaënsis genomes. These 10 Arachis putative GolS proteins ranged from 311 to 341 amino acids in length (average of 328) without signal peptides (Table 1). Phylogenetic analysis performed with the 40 putative GolS proteins revealed two distinct clusters: cluster 1, with 15 proteins, and cluster 2 with 25 (Fig. S1a). Arachis GolS proteins had representatives in both clusters, with six proteins in cluster 1 and four in cluster 2 (Fig. S1a).

Phylogenetic clustering was associated with the number of exons, with all genes coding the six proteins from cluster 1 consistently having three exons and those from cluster 2 having three to five exons (Fig. S1b). Three highly-conserved protein motifs were identified in the in the Arachis GolS family (Fig. S1c).

Raffinose synthase (RS) and stachyose synthase (STS)

Although the RS and the STS families have distinct EC codes, they are characterized by the presence of the same conserved GH36 family domain (PFAM domain PF05691). We found two plant proteins functionally characterized as belonging to the RS family and only one from the STS family in the CAZy database that were then used for the construction of separate RS and STS HMM profiles.

In total, 62 putative RS proteins were identified in 11 Fabaceae species in UniProt (Table S2). Another seven RS proteins were found in A. duranensis and six in A. ipaënsis, with an average length of 773 amino acids (ranging between 546 and 1,035) and lack of signal peptides (Table 1). Phylogenetic analysis of the 75 putative Fabaceae RS separated these proteins into seven distinct clusters (Fig. S2a). The Arachis RS proteins were evenly distributed among six clusters, with one protein per cluster, except for cluster 1, with two A. duranensis proteins (AdRS1 and AdRS2). As for GolS, RS protein clustering is related to its gene organization in Arachis, with genes belonging to the same cluster presenting a similar number of exons (Fig. S2b), which ranges from three exons in cluster 2 to more than 12 exons in clusters 1 and 3. The analysis of proteins sequences showed the presence of three conserved motifs in the 13 Arachis RS (Fig. S2c).

Fourteen putative STS proteins were retrieved from nine Fabaceae species (Table S2), including three from A. ipaënsis and only one from A. duranensis. These four putative STS Arachis proteins ranged from 359 to 1,696 amino acids in length (average of 945), without signal peptides (Table 1). Phylogenetic analysis revealed a highly conserved STS family in Fabaceae, forming two clusters: the first one with all proteins exclusive to the genus Arachis (AdSTS1, AiSTS1, AiSTS2 and AiSTS3) and the second with 10 proteins from other Fabaceae species (Fig. S3a). Exceptionally, no relationship was observed between this phylogenetic clustering and the intron/exon organization of the STS Arachis genes (Fig. S3b). The sequences of the four Arachis STS proteins showed at least three conserved motifs (Fig. S3c).

Alpha-galactosidase (AGAL)

AGAL is part of the GH27 enzyme family and is characterized by the presence of the conserved PFAM domain of melibiase_2 (PF16499). We retrieved three functionally characterized AGAL plant proteins from the CAZy database that were used to construct the HMM profile.

This profile revealed 56 putative AGAL proteins from 14 Fabaceae species (Table S2), from which four proteins belonged to A. duranensis and four to A. ipaënsis, with an average length of 374 amino acids, ranging from 178 to 437. Phylogenetic analysis divided these 56 putative AGAL proteins into three clusters (Fig. S4a). Clusters 2 and 3 each contain a single representative from A. duranensis and A. ipaënsis, whereas cluster 1 has two representatives from each species. Interestingly, the two A. duranensis (AdAGAL1 and AdAGAL2) and A. ipaënsis (AdAGAL1 and AdAGAL2) AGAL proteins that contained signal peptides shared the same cluster 1 (Table 1 and Fig. S4a). The Arachis proteins within the same cluster showed a similar intron/exon structure, except for those in cluster 3, where the A. duranensis AdAGAL4 gene had 15 exons while A. ipaënsis AiAGAL4 contained only seven (Fig. S4b). The protein sequence analysis showed that all eight Arachis AGAL proteins share at least three conserved common motifs (Fig. S4c).

Beta-fructofuranosidase (BFLUCT)

The BFLUCT enzyme family belongs to CAZy family GH32 and is also defined by the presence of two glycosyl hydrolase PFAM domains: Glyco_Hydro32N (PF00251) and Glyco_Hydro32C (PF08244). In the CAZy database, 78 plant proteins were functionally characterized as BFLUCT and we used the 11 Fabaceae proteins as references for the construction of an HMM profile.

A total of 114 putative BFLUCT proteins was retrieved from 13 Fabaceae species (Table S2), besides 11 proteins in A. duranensis and 13 in A. ipaënsis, with an average length of 552 amino acids, ranging from 140 to 676 (Table 1). Phylogenetic analysis produced five clusters, from which, four contained at least one representative of each Arachis species (Fig. S5a). Five A. duranensis and four A. ipaënsis BFLUCT proteins harbored signal peptides, but, unlike the AGAL proteins, these proteins did not share the same clusters (Fig. S5a). In general, the intron/exon organization of genes belonging to the same protein cluster was similar (Fig. S5b). Three protein motifs were identified and conserved in all Arachis BFLUCT, except for AdBFLUCT6 (Fig. S5c).

Genomic distribution and duplication patterns of RFO metabolism genes in wild Arachis

Genome-wide analysis of the two wild Arachis species with genome sequences so far available identified 28 RFO metabolism genes in A. duranensis and 31 in A. ipaënsis. In both species, these genes were unevenly distributed in the ten chromosomes regardless of the enzyme family (Fig. 1). The majority of the 59 genes were restricted to the distal chromosomal regions, in accordance with previous studies showing the gene-rich characteristic of these hot recombination hotspot regions in wild Arachis genomes23,25,40.

Genomic distribution of RFO metabolism Arachis genes. Distribution of galactinol synthase (GolS), raffinose synthase (RS), stachyose synthase (STS), alpha-galactosidase (AGAL) and beta-fructofuranosidase (BFLUCT) genes in the ten chromosomes of Arachis duranensis (A01–A10) and A. ipaënsis (B01–B10). Synteny between the two genomes is represented by lines. GolS (purple), STS (yellow), RS (green), AGAL (blue) and BFLUCT (red). The figure was generated by Circa software (https://omgenomics.com).

All the genes identified as involved in raffinose metabolism were duplicated in both Arachis species. The majority of gene copies (50.8%) resulted from dispersed duplications, 35.6% originated from whole-genome (WGD)/segmental duplication, 8.5% from proximal duplication and 5.1% from tandem duplications (Table 1). In the GolS family, specifically, the gene copies resulted mostly from WGD/segmental duplications (80%), while in the RS and AGAL families, the dispersed gene duplications represented the majority (92.3% and 75%, respectively; Table 1). Expansion of STS family genes similarly resulted from tandem and dispersed duplications (50% each) and the BFLUCT family from WGD/segmental and dispersed duplications (41.7% each) (Table 1).

Expression profiling of Arachis RFO metabolism genes in response to water deficit

The expression patterns of the 28 A. duranensis RFO metabolism genes in response to two types of drought imposition (dehydration and dry-down) were analyzed using our previous transcriptome data obtained from the drought-tolerant accession K7988 of A. duranensis and the drought-sensitive accession V10309 of A. stenosperma21. This analysis revealed that the expression of most of the genes involved in RFO metabolism were modulated in response to water deficit, with distinct patterns and expression levels depending on the type of stress imposed and, to a lesser extent, on the Arachis genotype (Fig. 2).

Expression profiling of RFO metabolism Arachis genes. Heatmap of the 28 transcripts identified as involved in RFO metabolism (GolS; RS; STS; AGAL and BFLUCT) in Arachis spp. Expression patterns (log2-based values from RNA-seq data) of Arachis duranensis genes and A. stenosperma orthologs were determined in plants submitted to drought (dry-down) imposed by the gradual decrease in soil water availability and to dehydration by withdrawal of hydroponic nutrient solution. The heatmap was generated by ggplot2 version 3.1 in Rstudio.

The Arachis RS genes exhibited small variations in their expression levels in response to the two types of drought imposition in both genotypes. The exception was AdRS6 with an high upregulation (fold change > 3) under dry-down in A. stenosperma (Fig. 2). Concerning the single representative of the STS family, AdSTS1 was moderately downregulated in both Arachis genotypes in response to the two stresses.

The expression profile of the four representatives of the AGAL family, the initial enzyme responsible for raffinose breakdown, was different in the two treatments, regardless of the Arachis genotype (Fig. 2). Under dehydration stress, AGAL genes exhibited an overall downregulation pattern, with low expression levels, whereas under the dry-down stress, they did not seem to be modulated. Likewise, most of the 11 A. duranensis BFLUCT genes were downregulated in response to the dehydration treatment whilst only being slightly affected by dry-down (Fig. 2). The exception was AdBFLUCT3, which was strongly induced (fold change > 10) in A. duranensis plants submitted to dry-down.

Genes coding for the five GolS showed contrasting expression behaviors in response to the two types of drought imposition, regardless of the Arachis genotype, with a general upregulation under dehydration and downregulation under dry-down (Fig. 2). This was especially evident for AdGolS4 and AdGolS5, which exhibited strong upregulation (fold change > 4) in response to dehydration. AdGolS2 was the only GolS gene downregulated in response to dehydration.

However, AdGolS3 drew particular attention as it exhibited the greatest difference in expression between the dehydration (upregulation of 3.15-fold) and dry-down (downregulation of − 8.16-fold) treatments in the drought-tolerant A. duranensis (Fig. 2). Conversely, in the more drought-sensitive A. stenosperma, the difference in the expression magnitude between dehydration (upregulation of 2.19-fold) and the dry-down (downregulation of − 1.75-fold) was much smaller (Fig. 2). AdGolS3 is also the orthologue of Arabidopsis AtGolS2, which is known to be responsive to diverse abiotic stresses, and confers enhanced drought tolerance when overexpressed in transgenic plants41. Given its differential regulation in drought tolerant and sensitive Arachis species, and orthologous relationship to AtGolS2, we therefore selected AdGolS3 for further in planta functional studies, to better understand the role of GolS genes in the molecular response underlying the process of water loss in wild Arachis.

Screening of A. thaliana lines overexpressing AdGolS3

The AdGolS3 coding sequence was predicted by the alignment of five sequences: Aradu.ZK8VV (https://peanutbase.org); GW944818.1; XM_016113210.2; HP005973.1 TSA and GW952716.1 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). The consensus sequence of 981 bp was cloned into pPZP-AdGolS3 and used to produce T0 primary Arabidopsis transformants. A total of 13 independent homozygous OE lines at T2 generation were obtained and AdGolS3 overexpression was confirmed by qRT-PCR analysis in all of these OE lines, with the expression levels relative to the two reference genes varying among individual lines (Fig. S6). AdGolS3 expression was not detected in WT plants.

Given the putative involvement of AdGolS3 in the synthesis of raffinose series sugars, the leaf sugar content in the 13 OE lines was also analyzed and compared to WT plants. Leaves from four OE lines (GolS10; GolS17; GolS20 and GolS22) showed a significantly higher level of raffinose compared to WT plants, whereas four (GolS2; GolS4; GolS6, and GolS8) unexpectedly had a significant decrease (p < 0.05, Fig. S7). There was no clear relationship between the transgene expression levels (Fig. S6) and raffinose contents (Fig. S7) in the 13 OE lines, consistent with the complex relationship between transcript abundance and accumulation of metabolites that lie downstream of the encoded enzyme. Overall, the content of other sugars also involved in RFO metabolism (glucose, fructose and sucrose) was not affected by AdGolS3 overexpression (Fig. S7). The exception was the GolS20 OE line, which presented an indirect, and specific, effect in its overall sugar content, with a significant increase in the concentration of all four sugars (glucose, fructose, sucrose and raffinose) compared to WT (Fig. S7). Interestingly, this OE line showed one of the lowest levels of ectopic AdGolS3 expression (Fig. S6). Based on these findings, and given previous reports of correlations between accumulation of RFOs and tolerance to stress3,5, the three promising OE lines that showed the highest levels of raffinose accumulation with variable levels of transgene expression (GolS17, GolS20 and GolS22) were selected for further stress assays and physiological and biochemical analyses.

Analysis of Arabidopsis plants overexpressing AdGolS3

Plant growth, relative water content (RWC) and electrolyte leakage (EL)

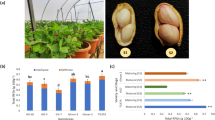

Over the 20 days of the dry-down assay, the morphology of the aerial part of the AdGolS3 OE lines remained similar to that of WT plants under normal irrigation conditions (CTR group) (Fig. 3). In the STR and REH groups, WT plants displayed severe morphological damage (leaf wilt) after 20 days without irrigation, whereas OE lines exhibited fewer symptoms of water deficiency (Fig. 3). In the REH group, one day after rehydration, transgenic plants recovered faster than WT, indicating that the AdGolS3 overexpression increased the ability of plants to recover their normal phenotype, as that observed in CTR group.

Phenotype of A. thaliana plants submitted to three treatments. Wild-type (WT) plants and three AdGolS3 OE lines (GolS17, GolS20 and GolS22) submitted to three treatments: Control group maintained under irrigation (70% FC); Stressed group where irrigation was suspended for 20 days; and Rehydrated group where irrigation was suspended for 20 days followed by irrigation for 24 h. Each plant is a distinct individual and is representative of each treatment group.

Plants submitted to dehydration for 20 days (STR and REH groups) had less shoot biomass when compared to the CTR group, with no significant differences between WT and OE lines (Fig. 4a). The analysis of the leaf relative water content (RWC) in plants maintained under CTR conditions showed values of 85–86%, typical of turgid leaves, with no differences between WT and OE lines (Fig. 4b). An overall reduction in RWC was observed when plants were submitted to STR conditions when compared to CTR. Under dehydration imposition, the three OE lines displayed RWC values higher than WT plants, with the GolS22 OE line showing a significant difference of 25%. Following 24 h of rehydration, both GolS17 and GolS22 OE lines reached higher RWC values than WT plants, comparable to those found for plants under CTR conditions, indicating their ability to rapidly recover to a high leaf water status in response to water availability (Fig. 4b). Accordingly, the opposite behavior was observed for leaf electrolyte leakage (EL) measurements at the end of the dry-down assay, with a significantly lower leakage in the GolS22 line under stressed conditions and in the GolS17 and GolS22 lines following rehydration, as compared to the WT plants (Fig. 4c), representing good evidence of cell membrane stability under stress in these OE lines. Interestingly, GolS17 and GolS22 lines showed significant differences in EL values compared to WT plants, even when plants were maintained under CTR conditions (Fig. 4c). RWC and EL measurements have been widely used to reflect, respectively, water loss control and membrane stability in plants submitted to water-limited conditions, and therefore an improvement in drought tolerance. These results could thus indicate that AdGolS3 overexpression increases plant tolerance to water deficit stress.

Performance of A. thaliana plants under the dry-down treatment. Wild-type (WT) plants and three AdGolS3 OE lines (GolS17, GolS20 and GolS22) submitted to a dry-down treatment for 20 days (Stressed group), followed by 24 h of rehydration (Rehydrated group) and the corresponding irrigated (70% FC) control (Control group). (a) Shoot biomass (grams of fresh weight per plant). (b) Percentage of leaf relative water content (RWC). (c) Percentage of leaf electrolyte leakage (EL). Bars represent value means and standard errors. * and + indicate statistically significant differences compared to control WT plants for each OE line (T-test, n = 7–10, p < 0.05 and p < 0.1 respectively).

Soluble sugar content and metabolic profiling

Soluble sugar (glucose, sucrose and raffinose) abundance in leaves of WT and OE lines (GolS17, GolS20 and GolS22) under CTR, STR and REH conditions were also analyzed. Despite the highly variable absolute concentration of these sugars, previously determined for the 13 OE lines under CTR condition only (Fig. S7), the relative percentage abundance was generally stable in the GolS17, GolS20 and GolS22 lines, regardless of the treatment applied (Fig. S8). The abundance of raffinose relative to glucose and sucrose was indeed higher in the GolS17 and GolS22 OE lines compared to WT plants under CTR conditions. These results corroborated the previous analysis of the absolute raffinose concentration (Figs. S7 and S8). Also, the relative abundance of raffinose did not differ between GolS20 and WT plants under CTR conditions, but it significantly increased from 2.5 to 12.9% when GolS20 plants was submitted to STR conditions (Fig. S8). Conversely, the relative abundance of raffinose in the GolS17 OE line significantly decreased from 7.6% of total sugars under CTR conditions to 3.9% when plants were rehydrated. Interestingly, the ratio between glucose and sucrose relative abundance was almost stable (around 1:1), and apparently independent of the treatment (CRT, STR or REH). In contrast, the ratio between raffinose and these sugars was more variable (Fig. S8).

To further characterize the metabolic response of the AdGolS3 OE lines under STR and REH conditions, we carried out GC–MS based metabolite profiling of leaf tissues (Table 2 and Fig. S9). Overall, few differences between the WT and OE lines were detected in the metabolic profile regardless of the treatment. Under CTR conditions, GolS17 contained less sucrose whilst GolS22 contained more raffinose and galactinol than WT, mirroring the results obtained by HPAE (Table 2; Figs. S7, S8 and S9a). When expressed relative to all detected metabolites abundances of both raffinose and galactinol were also greater in GolS17 than in WT (Table 2 and Fig. S9b), again reflecting a shift in metabolite profile towards raffinose accumulation. As well as these alterations in sugars, citrate concentrations were also higher in GolS20 and threonate concentrations lower in GolS22 under CTR conditions. Under STR condition, the only difference was an increased concentration of putrescine in the GolS22 line compared to WT. Under the REH, when expressed relative to all detected metabolites, raffinose and galactinol in GolS22 remained greater than in WT (Table 2 and Fig. S9).

As anticipated, greater differences were observed between stressed and non-stressed control plants of the same genotype (WT and each OE line) (Table 2 and Fig. S9a). In stressed WT plants, for example, 13 out 26 metabolites showed increased concentrations, including alanine, beta-alanine, aspartate, citrate, fructose, galactinol, glucose, glycerol, myo-inositol, leucine, raffinose, threonate, and valine (Table 2 and Fig. S9a). GolS17 metabolism was similarly affected, with a total of 17 different metabolites showing significant alterations under stressed conditions. Fewer changes, however, were detected in both GolS20 and GolS22 OE lines, as only three (galactinol, myo-inositol and raffinose), and six (beta-alanine, fructose, gluconate, myo-inositol, leucine and valine) metabolites were significantly perturbed by the drought imposition, respectively. Myo-inositol was the only metabolite with increased abundance under stress in all genotypes (Table 2). Whilst large increases in proline were detected in individual samples, the only significant increase was in stressed GolS17 plants relative to their non-stressed controls. Rehydration generally led to metabolite concentrations returning to the levels observed in control conditions. One notable exception was that of myo-inositol, which remained at elevated concentrations relative to control plants for WT, GolS17 and GolS20 (Table 2).

NaCl and PEG treatments

Additional analysis of GolS22 and WT plants grown under well-irrigated CTR, salt stress (irrigated with NaCl 150 mM) and osmotic stress (irrigated with PEG 20%) conditions was conducted after 15 days of treatment. The phenotype of the GolS22 transgenic plants was similar to that of WT under CTR conditions, with RWC values (78% and 74%, respectively) typical of turgid leaves (Fig. 5a). Similar RWC values for WT and GolS22 plants (65% and 61%, respectively) were maintained even when salt stress treatment was applied; however, RWC was significantly greater in GolS22 (62%) under osmotic stress (Fig. 5a). EL values in the GolS22 line were significantly lower than in WT plants under both stress conditions (NaCl and PEG) (Fig. 5b), as previously observed for drought and rehydration (Fig. 4c) treatments. Together, these results indicate that overexpression of AdGolS3 led to better water retention and membrane stability not only during drought imposition and rehydration recovery but also under both salt and osmotic stresses.

Performance of A. thaliana plants under the NaCl and PEG treatments. Wild-type (WT) plants and the AdGolS3 OE line GolS22 submitted to salt stress (irrigated with 150 mM NaCl) and osmotic stress (irrigated with PEG 6,000 20%) treatments for 15 days and the corresponding irrigated (70% FC) Control. (a) Percentage of leaf relative water content (RWC). (b) Percentage of leaf electrolyte leakage (EL). Bars represent value means and standard errors. * indicate statistically significant differences compared to control WT plants for GolS22 OE line (T-test, n = 11 or 12, p < 0.05).

qRT-PCR expression analysis

Considering that AdGolS3 overexpression enhanced drought tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis, altering sugar and metabolic profiles, the expression levels of a subset of six genes was evaluated. This subset comprises the AtGolS2 gene, which is the AdGolS3 ortholog in Arabidopsis, and five other Arabidopsis genes coding for proteins that putatively interact with AtGolS2 based on a predicted protein–protein interaction network (Fig. S10). These genes were also selected based on their known involvement in drought and osmotic stress responses. The expression analysis of the six genes was carried out by qRT-PCR in roots from three OE lines (GolS17, GolS20 and GolS22) and WT plants submitted to CTR, STR and REH conditions. As a whole, AdGolS3 overexpression by itself was sufficient to induce the expression of five (AtAPX1, AtCAT2, AtGSTU24, AtEMB2729 and AtGolS2) of the six Arabidopsis genes, given that their expression was higher in OE lines than in WT plants under CTR conditions. (Fig. 6a). Interestingly, under drought stress imposition, the expression behavior of four (AtAPX1, AtCAT2, AtGSTU24 and AtEMB2729) of these genes changed drastically with a general pattern of downregulation, and an average decrease of almost threefold in transcript levels when compared to CTR conditions (Fig. 6b).

qRT-PCR expression analysis in A. thaliana plants. Relative quantification of mRNA levels of six Arabidopsis genes (AtAPX1, AtCAT2, AtGSTU24, AtSAP13; AtEMB2729 and AtGolS2) in the three OE lines (GolS17; GolS20 and GolS22) relative to the wild-type (WT) plants, under (a) control, (b) stressed and (c) rehydrated conditions. Values are means ± SD of three biological replicates and the significant (p < 0.05) differences between WT and OE lines are marked with *.

After subsequent plant rehydration, the expression levels of these four genes increased, almost reaching the basal levels observed under CTR conditions (Fig. 6c). Conversely, the endogenous Arabidopsis GolS gene (AtGolS2) was the only gene for which the expression increased (4.12-fold) under drought imposition as compared to CTR conditions, with significant upregulation in all OE lines (Fig. 6b). However, despite its remarkable upregulation under STR conditions, the expression of the AtGolS2 gene rapidly dropped and returned to the basal CTR levels just 24 h after rehydration, as also observed for the other four genes (Fig. 6c). It is interesting that the expression of AtSAP13 was negatively affected by AdGolS3 overexpression, but not by dry-down or rehydration treatments, since its downregulation was maintained (average RQ of 0.81) in the three OE lines under all of the studied conditions (Fig. 6). These findings suggest that AdGolS3 may play an important role in drought-associated pathways by modulating the transcriptional dynamics of downstream genes.

Discussion

The majority of RFO metabolism genes have undergone dispersed duplications in wild Arachis

RFOs are part of the molecular network activated by plants in response to a range of environmental stresses and currently emerge as key components in stress tolerance, acting as osmoprotectants, antioxidants and signaling molecules2,4. Due to their importance, the principal enzymes involved in the first steps of RFO biosynthesis (GolS, RS and STS) have been thoroughly studied at the genome-wide scale in many plant species8,9,10,11,12,15. However, little attention has been given to the enzymes involved in RFO catabolism, such as AGAL and BFLUCT. These enzymes are equally important for the accumulation of RFOs in plants, but only few reports provide a comprehensive analysis of genes involved in both RFO biosynthesis and catabolism5,8,15.

The availability of A. duranensis and A. ipaënsis genomes25, the progenitors of peanut (A. hypogaea), enabled the genome-wide search for gene families and the assessment of their evolutionary history in these wild species. Here, a comprehensive analysis of five gene families (GolS, RS, STS, AGAL and BFLUCT) was conducted, which lead to the identification of 28 genes related to both RFO biosynthesis and catabolism in A. duranensis and 31 in A. ipaënsis. This is in accordance with the 35 RFO-related genes described for Z. mays8 and the 58 RFO-related loci identified in G. max15.

The phylogenetic analysis of putative RFO-related proteins from Fabaceae, including these five enzyme families identified in wild Arachis, showed a clear subdivision within each family, supported by high bootstrap values. This clustering, based on phylogenetic proximity, was related to the intron/exon organization of the corresponding Arachis genes, as previously observed for other plant species8,9,10. Similarly to the conservation of gene structure, amino acid sequences were highly conserved too, for example, the hydrophobic pentapeptide (APSAA), characteristic of the GolS family42, was found for all the proteins from A. duranensis and A. ipaënsis, as well as other conserved motifs in the different enzyme families.

The highly duplicated state of the genes involved in raffinose metabolism is consistent with previous descriptions for other gene families in wild Arachis, such as expansin and NBS-LRR families23,40, however, this was not observed for the dehydrin family22. The majority of the wild Arachis RFO metabolism genes have undergone dispersed duplications. Conversely, the genes from the GolS family have undergone duplication mostly by WGD and can be observed in gene blocks in two different chromosomes. Other studies also found that segmental duplications were the driving force for the expansion of GolS genes in S. indicum and Rosaceae genomes, being associated with a possible subfunctionalization10,12.

The expression profiling of wild Arachis genes differed according to the water-deficit treatment

Wild and cultivated Arachis genotypes exhibit contrasting transpiration behaviors under water-limited conditions, with variable levels of water stress tolerance among the wild species43. Accordingly, the accessions K7988 of A. duranensis and V10309 of A. stenosperma have been selected as the drought-tolerant and the drought-sensitive genotypes, respectively, in our functional genomics studies18,20,21,23,24. Here, the comprehensive expression analysis conducted in these genotypes revealed that most of the 28 A. duranensis genes involved in RFO metabolism, and their orthologs in A. stenosperma, are responsive to drought imposition.

Overall, the expression profiling of these genes indicated that, in wild Arachis, the molecular responses necessary to trigger RFO biosynthesis, accumulation, and eventually catabolism, differed according to the severity of the water loss process, as demonstrated for resurrection plants44. As GolS is the first committed enzyme and the key regulator of the RFO pathway, its general induction in Arachis roots submitted to dehydration could be a rapid transcriptional response to the severe process of water loss during air-drying. However, over the 150 min time frame of the experiment, increased levels of GolS transcripts seem to be insufficient to allow the observation of the expected increase in the expression of the downstream genes involved in the subsequent steps of RFO biosynthesis (RS and STS). Similar comprehensive expression profiles of GolS, RS and STS genes were observed in response to water-deficit treatments in S. indicum, M. esculenta and G. max9,10,15. Also, genes involved in RFO catabolism (AGAL and BFLUCT) were downregulated in response to this severe water-limited condition. It suggested the role of some members of these two multigene families in the transcriptional regulatory networks of drought tolerance in Arachis. Conversely, the moderate drought process imposed by four days of soil drying did not appear to affect the expression of GolS genes in Arachis. Under this moderate stress condition, the subsequent steps of the RFO metabolic pathway were also not yet induced, and accordingly, the transcript levels of genes coding for the enzymes that participate in RFO biosynthesis (RS and STS) and catabolism (AGAL and BFLUCT) were kept rather constant or slightly repressed.

AdGolS3 showed opposite expression behavior between drought-tolerant and drought-sensitive wild Arachis

The overexpression of GolS genes leads to enhanced tolerance to abiotic stresses (drought, salt, heavy metal, cold and heat), by increasing galactinol and RFO contents in transgenic dicots and monocot species41,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52. These transgenes were isolated from a number of plant species being the AtGolS2 gene from Arabidopsis, the most commonly used. An AtGolS2 ortholog has been isolated from Thellungiella salsuginea, and its overexpression also resulted in improved tolerance to abiotic stress in transgenic plants53. Besides being the ortholog of AtGolS2 in A. duranensis, the AdGolS3 gene was selected for further functional analysis since it exhibited differential expression behavior between the drought-tolerant A. duranensis and the drought-sensitive A. stenosperma, in both severe and moderate water-limited conditions. Moreover, our previous qRT-PCR expression analysis21 showed that AdGolS3 had a higher magnitude of expression in the tolerant A. duranensis throughout the dehydration treatment. Together, these findings indicate AdGolS3 as a putative regulator gene of the RFO pathway in the A. duranensis drought tolerance mechanisms that could be involved in the early and differential responses to severe and moderate processes of water loss.

Overexpression of AdGolS3 in Arabidopsis increased water retention, maintained membrane integrity and altered metabolic profile

Under water deficit and PEG-mediated osmotic stress, and following rehydration, Arabidopsis AdGolS3 OE lines exhibited higher RWC values than WT plants, indicating less water loss. The capacity of transgenic plants to maintain high leaf water status under abiotic stresses, as expressed in higher RWC, was also observed in some crop species overexpressing GolS genes, such as rice, poplar and chickpea46,49,54. This greater water retention in transgenic plants due to GolS overexpression may reflect a better uptake of soil water by roots and/or lower transpiration. It could increase their efficiency in the control of stomatal opening under water deficit conditions, as previously shown in transgenic Brachypodium distachyon plants48. We also observed a reduced EL when OE lines were submitted to drought, salinity and osmotic stresses, and following rehydration, indicating that AdGolS3 overexpression attenuated the damage of cell membranes. The electrolyte leakage results from loss of cell membrane integrity caused by the generation of ROS in plants submitted to stress conditions and is commonly used to estimate the degree of the membrane injury. Our findings suggested that the overexpression of AdGolS3 led to a common mechanism to respond to, at least, three different types of abiotic stresses (drought, salinity and osmotic), which involves better water retention and less damage to the plasma membrane, as previously suggested by48,50,53. The maintenance of plant water relations and cell membrane integrity have been considered important factors contributing to abiotic stress tolerance.

In addition, overexpression of AdGolS3 resulted in Arabidopsis plants with increased concentrations of few metabolites, including galactinol, product of GolS enzyme activity, and a direct precursor of raffinose. Accordingly, leaf raffinose concentrations were also higher in OE lines than in WT plants as well as raffinose representing a greater proportion of leaf sugar. As expected, when drought stress was imposed the metabolic profile in WT plants changed drastically, with increased levels of most metabolites. Nevertheless, few metabolites were altered in GolS20 and GolS22 OE lines in response to drought stress, which exhibited an overall similar metabolic profile to non-stressed CTR conditions. This suggests that AdGolS3 overexpression in these two lines may have led to a reduction in the metabolic perturbation caused by water deficit. Interestingly, qRT-PCR analysis showed that the expression of the endogenous Arabidopsis AtGolS2 gene was also highly induced in response to drought stress in all OE lines compared to WT. It is likely to have contributed to increased galactinol accumulation with minor alterations in the metabolite profile of transgenic plants. The AtGolS2 gene is known to be induced in Arabidopsis by drought and salinity stresses and is directly regulated by the heat shock transcription factors41,55.

Following rehydration, most metabolite concentrations in WT plants and OE lines returned roughly to levels found in non-stressed plants. However, myo-inositol concentrations remained elevated in WT plants and two of the OE lines, possibly due to its role as one of the principal metabolites, together with galactinol, of the classical RFO pathway3.

The ability of AdGolS3 to improve the tolerance to three different types of abiotic stresses corroborates previous studies that signal GolS as a regulator of the synthesis of galactinol and raffinose, and indirectly other sugars, in stress-tolerant transgenic plants41,46,48,49,50,51,52,53. This may be related to the multiple putative functions of these oligosaccharides in plants. Raffinose may act to stabilize sensitive macromolecular structures and membranes under stress as well as act as an osmolyte48. Besides, such sugars represent also essential sources of energy, not only during germination but during recovery from a variety of abiotic stresses. Furthermore, galactinol and raffinose may also scavenge hydroxyl radicals, leading to oxidative stress defense56,57,58.

Overexpression of AdGolS3 in Arabidopsis modulated the expression of genes involved in plant protection against oxidative damage

Whilst ROS have important signaling roles in plant defense mechanisms, their increased production in response to stress can damage cellular components and is often accompanied by harmful effects on basic cellular processes4, 59. Plants have evolved detoxification mechanisms to control the excess accumulation of ROS that include antioxidant enzymes, such as catalase (CAT), ascorbate peroxidase (APX), and glutathione S-transferase (GST). CAT converts H2O2 into H2O and O2 and is induced by multiple abiotic stresses60. Likewise, APX is responsible for the removal of H2O2 and its activity increases in response to stress exposure whereas the knockout of its cytosolic isoforms reduced tolerance to a variety of abiotic stresses61. GSTs, such as that encoded by AtGSTU24, have both catalytic and non-catalytic activities that allow them to act in a variety of plant defense strategies, such as antioxidant regulation, adaptation and tolerance to abiotic constraints and pathogen resistance62,63.

Given that the AdGolS3 OE lines exhibited increased stress tolerance, we analyzed the expression of genes coding for these three antioxidant enzymes in Arabidopsis. The expression behavior of AtCAT2; AtGSTU24 and AtAPX1 was similar, with increased transcript levels as a result of AdGolS3 overexpression, which dropped to a pattern of downregulation when plants were submitted to STR and REH conditions.

The overexpression of AdGolS3 therefore coincided with accumulation of transcripts of at least the three antioxidant enzyme-coding genes that could potentially increase plant capacity to detoxify ROS, as indicated by their expression profile under CTR conditions, though the mechanistic link between these observations is unclear. Moreover, and consistent with our analysis of electrolyte leakage, lower antioxidant enzyme transcript levels under drought stress suggests that the AdGolS3 overexpression plants suffer from less oxidative than WT plants. This could be due to the action of RFOs as non-enzymatic antioxidants56,64, or due to their action in maintaining plant water content and protecting against the negative effects of desiccation. Additional experiments, including measurement of antioxidant enzyme activities and ROS quantification, will be required to determine how RFOs act in the context of AdGolS3 overexpression.

The potential roles of AtSAP13 and AtEMB2729, genes with altered expression in Arabidopsis OE lines

Following identification of proteins that putatively interact with AtGolS2, we carried out expression analysis of a member of the “Stress-Associated Protein” family (AtSAP13) and a member of the alpha-amylase protein family (AtEMB2729). These genes displayed opposite expression behaviors, with AtSAP13 consistently being downregulated in OE lines regardless of the conditions studied (CTR, STR and REH), and AtEMB2729 being induced under these conditions. Whilst the mechanism of action of SAP family, a class of zinc-finger proteins with A20/AN1 domains, remains unknown, they have been considered as novel regulators (positive or negative) of stress signaling mediated by abscisic acid (ABA) and some representatives of the SAP family displayed a negative role in stress tolerance, by increasing plant sensitivity to drought, cold and salinity65,66. Likewise, little is known about the contribution of the AtEMB2729 gene (also designated as branching enzyme 1, BE1) to abiotic stress responses67. Besides playing a critical function in embryogenesis and maintenance of carbohydrate homeostasis, BE1 genes may also act in the regulation of auxin and cytokinin metabolism67,68. The induction of AtEMB2729 in AdGolS3 OE lines was consistent with a potential role in regulating sugar metabolism under abiotic stress conditions. Elucidation of the function of these genes in stress tolerance and their functional relationship with AtGolS2 and RFO metabolism will, however, require further investigation including phytohormone profiling.

Improved tolerance to abiotic stresses and accumulation of antinutritional effects

In the present study, the overexpression of the AdGolS3 gene increased the abundance of galactinol and raffinose in transgenic Arabidopsis plants and conferred tolerance to drought, salt and osmotic stresses. These results therefore corroborate previous reports demonstrating that the overexpression of GolS genes can successfully impart tolerance to multiple abiotic stresses in the models Arabidopsis and tobacco5 and also in crop species such as rice, soybean, tomato, and poplar45,46,49,52. It is worth noting, however, that the natural accumulation of RFOs in mature seeds to protect the embryo from desiccation is considered an antinutritional factor for many grain legumes13,17. Thus, the reduction of RFO content, or even their removal, to improve digestibility and nutritional quality of seeds, has been the focus of many legume breeding programs16. It includes the development of transgenic plants by the antisense/RNAi suppression of RFO-synthesizing genes or by the overexpression of RFO-degrading genes69. Therefore, the consistent benefits regarding abiotic stress tolerance of transgenic plants overexpressing GolS genes could come with the potential drawback: higher contents of RFOs in their mature seeds.

Conclusions

In the present work, we studied five key enzymes (GolS; RS; STS; AGAL and BFLUCT) involved in the biosynthesis and catabolism of RFOs in legumes, with an emphasis on wild relatives of peanut, A. duranensis and A. ipaënsis. This represents the first genome-wide survey of genes associated with RFO metabolism in wild Arachis, including those responsive to drought. Furthermore, the overexpression of AdGolS3 gene, encoding a galactinol synthase isolated from A. duranensis, led to increased raffinose production and tolerance to drought, salt and osmotic stresses in transgenic Arabidopsis. In addition to alterations in metabolite profile, the overexpression of AdGolS3 modulated the expression of antioxidant genes, suggesting a protective effect in preventing oxidative damage of plant cells. AdGolS3 is, therefore, a promising candidate gene for introduction in transgenic crops to increase their tolerance to abiotic stresses, though potential impacts on seed nutritional quality must be considered, particularly in legume crop engineering.

References

Kollist, H. et al. Rapid responses to abiotic stress: Priming the landscape for the signal transduction network. Trends Plant Sci. 24, 25–37 (2019).

Guerra, D. et al. Post-transcriptional and post-translational regulations of drought and heat response in plants: A spider’s web of mechanisms. Front. Plant Sci. 6, 57 (2015).

ElSayed, A. I., Rafudeen, M. S. & Golldack, D. Physiological aspects of raffinose family oligosaccharides in plants: Protection against abiotic stress. Plant Biol. 16, 1–8 (2014).

Sami, F., Yusuf, M., Faizan, M., Faraz, A. & Hayat, S. Role of sugars under abiotic stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 109, 54–61 (2016).

Sengupta, S., Mukherjee, S., Basak, P. & Majumder, A. L. Significance of galactinol and raffinose family oligosaccharide synthesis in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 6, 656 (2015).

Liu, J. J., Odegard, W. & De Lumen, B. O. Galactinol synthase from kidney bean cotyledon and zucchini leaf (purification and N-terminal sequences). Plant Physiol. 109, 505–511 (1995).

Peterbauer, T. & Richter, A. Biochemistry and physiology of raffinose family oligosaccharides and galactosyl cyclitols in seeds. Seed Sci. Res. 11, 185–197 (2001).

Zhou, M.-L. et al. Genome-wide identification of genes involved in raffinose metabolism in Maize. Glycobiology 22, 1775–1785 (2012).

Li, R. et al. Genome-wide identification and expression profiling analysis of the galactinol synthase gene family in cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz). Agronomy 8, 1–17 (2018).

You, J. et al. Genome-wide identification and expression analyses of genes involved in raffinose accumulation in sesame. Sci. Rep. 8, 1–11 (2018).

Filiz, E., Ozyigit, I. I. & Vatansever, R. Genome-wide identification of galactinol synthase (GolS) genes in Solanum lycopersicum and Brachypodium distachyon. Comput. Biol. Chem. 58, 149–157 (2015).

Falavigna, V. D. S. et al. Evolutionary diversification of galactinol synthases in Rosaceae: Adaptive roles of galactinol and raffinose during apple bud dormancy. J. Exp. Bot. 69, 1247–1259 (2018).

Obendorf, R. L. & Górecki, R. J. Soluble carbohydrates in legume seeds. Seed Sci. Res. 22, 219–242 (2012).

Salvi, P. et al. Differentially expressed galactinol synthase (s) in chickpea are implicated in seed vigor and longevity by limiting the age induced ROS accumulation. Sci. Rep. 6, 35088 (2016).

Ferreira-Neto, J. R. C. et al. Inositol phosphates and Raffinose family oligosaccharides pathways: Structural genomics and transcriptomics in soybean under root dehydration. Plant Gene 20, 100202 (2019).

Silva, L. C. C. et al. Effect of a mutation in Raffinose Synthase 2 (GmRS2) on soybean quality traits. Crop Breed. Appl. Biotechnol. 19, 62–69 (2019).

Toomer, O. T. Nutritional chemistry of the peanut (Arachis hypogaea). Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 58, 3042–3053 (2018).

Guimaraes, P. M., Brasileiro, A. C. M., Mehta, A. & Araujo, A. C. G. Functional genomics in peanut wild relatives. In The Peanut Genome—Compendium of Plant Genomes (eds Varshney, R. K. et al.) 149–164 (Springer International Publishing, Berlin, 2017).

Guimaraes, P. M. et al. Global transcriptome analysis of two wild relatives of peanut under drought and fungi infection. BMC Genom. 13, 387 (2012).

Brasileiro, A. C. M. et al. Transcriptome profiling of wild Arachis from water-limited environments uncovers drought tolerance candidate genes. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 33, 1–17 (2015).

Vinson, C. C. et al. Early responses to dehydration in contrasting wild Arachis species. PLoS ONE 13, 2 (2018).

Mota, A. P. Z. et al. Contrasting effects of wild Arachis dehydrin under abiotic and biotic stresses. Front. Plant Sci. 10, 1–16 (2019).

Guimaraes, L. A. et al. Genome-wide analysis of expansin superfamily in wild Arachis discloses a stress-responsive expansin-like B gene. Plant Mol. Biol. 94, 1–18 (2017).

Carmo, L. S. T. et al. Comparative proteomics and gene expression analysis in Arachis duranensis reveal stress response proteins associated to drought tolerance. J. Proteom. 192, 2 (2019).

Bertioli, D. J. et al. The genome sequences of Arachis duranensis and Arachis ipaensis, the diploid ancestors of cultivated peanut. Nat. Genet. Adv. 2, 2 (2016).

Lombard, V., Golaconda Ramulu, H., Drula, E., Coutinho, P. M. & Henrissat, B. The carbohydrate-active enzymes database (CAZy) in 2013. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, 490–495 (2013).

Katoh, K. & Standley, D. M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 772–780 (2013).

Capella-Gutiérrez, S., Silla-Martínez, J. M. & Gabaldón, T. trimAl: A tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics 25, 1972–1973 (2009).

Eddy, S. R. Accelerated profile HMM searches. PLoS Comput. Biol. 7, e1002195 (2011).

Fu, L., Niu, B., Zhu, Z., Wu, S. & Li, W. CD-HIT: Accelerated for clustering the next-generation sequencing data. Bioinformatics 28, 3150–3152 (2012).

Chu, Y. et al. A technique to study Meloidogyne arenaria resistance in Agrobacterium rhizogenes-transformed peanut. Plant Dis. 98, 1292–1299 (2014).

Clough, S. J. & Bent, A. F. Floral dip: A simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 16, 735–743 (1998).

Moreira, T. B. et al. A genome-scale metabolic model of soybean (Glycine max) highlights metabolic fluxes in seedlings. Plant Physiol. 180, 1912–1929 (2019).

de Brito, G. G., Sofiatti, V., de Andrade Lima, M. M., de Carvalho, L. P. & Filho, J. L. Physiological traits for drought phenotyping in cotton. Acta Sci. Agron. 33, 117–125 (2011).

Whitlow, T. H., Bassuk, N. L., Ranney, T. G. & Reichert, D. L. An improved method for using electrolyte leakage to assess membrane competence in plant tissues. Plant Physiol. 98, 198–205 (1992).

Lisec, J., Schauer, N., Kopka, J., Willmitzer, L. & Fernie, A. R. Gas chromatography mass spectrometry–based metabolite profiling in plants. Nat. Protoc. Ed. 1, 387 (2006).

Lommen, A. Metalign: Interface-driven, versatile metabolomics tool for hyphenated full-scan mass spectrometry data preprocessing. Anal. Chem. 81, 3079–3086 (2009).

Warde-Farley, D. et al. The GeneMANIA prediction server: biological network integration for gene prioritization and predicting gene function. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, W214–W220 (2010).

Morgante, C. V. et al. Reference genes for quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction expression studies in wild and cultivated peanut. BMC Res. Notes 4, 339 (2011).

Mota, A. P. Z. et al. Comparative root transcriptome of wild Arachis reveals NBS-LRR genes related to nematode resistance. BMC Plant Biol. 18, 2 (2018).

Taji, T. et al. Important roles of drought and cold inducible genes for galactinol synthase in stress tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 29, 417–426 (2002).

Peters, S., Mundree, S. G., Thomson, J. A., Farrant, J. M. & Keller, F. Protection mechanisms in the resurrection plant Xerophyta viscosa (Baker): Both sucrose and raffinose family oligosaccharides (RFOs) accumulate in leaves in response to water deficit. J. Exp. Bot. 58, 1947–1956 (2007).

Leal-Bertioli, S. C. M. et al. The effect of tetraploidization of wild Arachis on leaf morphology and other drought-related traits. Environ. Exp. Bot. 84, 17–24 (2012).

Zhang, Q. & Bartels, D. Molecular responses to dehydration and desiccation in desiccation-tolerant angiosperm plants. J. Exp. Bot. 69, 3211–3222 (2018).

Liu, Y. et al. Expression of galactinol synthase from Ammopiptanthus nanus in tomato improves tolerance to cold stress. J. Exp. Bot. 71, 435–449 (2020).

Selvaraj, M. G. et al. Overexpression of an Arabidopsis thaliana galactinol synthase gene improves drought tolerance in transgenic rice and increased grain yield in the field. Plant Biotechnol. J. 15, 1465–1477 (2017).

Wang, Y., Liu, H., Wang, S., Li, H. & Xin, Q. Overexpression of a common wheat gene Galactinol synthase3 enhances tolerance to zinc in Arabidopsis and rice through the modulation of reactive oxygen species production. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 34, 794–806 (2016).

Himuro, Y. et al. Arabidopsis galactinol synthase AtGolS2 improves drought tolerance in the monocot model Brachypodium distachyon. J. Plant Physiol. 171, 1127–1131 (2014).

Yu, X. et al. Enhancement of abiotic stress tolerance in poplar by overexpression of key Arabidopsis stress response genes, AtSRK2C and AtGolS2. Mol. Breed. 37, 57 (2017).

Song, J. et al. Cloning of galactinol synthase gene from Ammopiptanthus mongolicus and its expression in transgenic Photinia serrulata plants. Gene 513, 118–127 (2013).

Zhuo, C. et al. A cold responsive galactinol synthase gene from Medicago falcata (MfGolS1) is induced by myo-inositol and confers multiple tolerances to abiotic stresses. Physiol. Plant. 149, 67–78 (2013).

Honna, P. T. et al. Molecular, physiological, and agronomical characterization, in greenhouse and in field conditions, of soybean plants genetically modified with AtGolS2 gene for drought tolerance. Mol. Breed. 36, 157 (2016).

Sun, Z. et al. Overexpression of TsGOLS2, a galactinol synthase, in Arabidopsis thaliana enhances tolerance to high salinity and osmotic stresses. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 69, 82–89 (2013).

Kamble, N. U. & Majee, M. Ectopic over-expression of ABA-responsive Chickpea galactinol synthase (CaGolS) gene results in improved tolerance to dehydration stress by modulating ROS scavenging. Environ. Exp. Bot. 171, 103957 (2019).

Song, C., Chung, W. S. & Lim, C. O. Overexpression of heat shock factor gene HsfA3 increases galactinol levels and oxidative stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. Mol. Cells 39, 477–483 (2016).

Nishizawa, A., Yabuta, Y. & Shigeoka, S. Galactinol and raffinose constitute a novel function to protect plants from oxidative damage. Plant Physiol. 147, 1251–1263 (2008).

Stoyanova, S., Geuns, J., Hideg, É & Van Den Ende, W. The food additives inulin and stevioside counteract oxidative stress. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 62, 207–214 (2011).

Hernandez-Marin, E. & Martínez, A. Carbohydrates and their free radical scavenging capability: A theoretical study. J. Phys. Chem. B 116, 9668–9675 (2012).

Mhamdi, A. & Van Breusegem, F. Reactive oxygen species in plant development. Development 145, 76 (2018).

Alam, N. B. & Ghosh, A. Comprehensive analysis and transcript profiling of Arabidopsis thaliana and Oryza sativa catalase gene family suggests their specific roles in development and stress responses. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 123, 54–64 (2018).

Shigeoka, S. & Maruta, T. Cellular redox regulation, signaling, and stress response in plants. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 78, 1457–1470 (2014).

Nianiou-Obeidat, I. et al. Plant glutathione transferase-mediated stress tolerance: Functions and biotechnological applications. Plant Cell Rep. 36, 791–805 (2017).

Abuqamar, S., Ajeb, S., Sham, A., Enan, M. R. & Iratni, R. A mutation in the expansin-like A 2 gene enhances resistance to necrotrophic fungi and hypersensitivity to abiotic stress in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Plant Pathol. 14, 813–827 (2013).

Jing, Y., Lang, S., Wang, D., Xue, H. & Wang, X.-F. Functional characterization of galactinol synthase and raffinose synthase in desiccation tolerance acquisition in developing Arabidopsis seeds. J. Plant Physiol. 230, 109–121 (2018).

Zhou, Y., Zeng, L., Chen, R., Wang, Y. & Song, J. Genome-wide identification and characterization of stress-associated protein (SAP) gene family encoding A20/AN1 zinc-finger proteins in Medicago truncatula. Arch. Biol. Sci. 70, 87–98 (2018).

He, X. et al. Genome-wide identification of stress-associated proteins (SAP) with A20/AN1 zinc finger domains associated with abiotic stresses responses in Brassica napus. Environ. Exp. Bot. 165, 108–119 (2019).

Wang, X., Xue, L., Sun, J. & Zuo, J. The Arabidopsis BE1 gene, encoding a putative glycoside hydrolase localized in plastids, plays crucial roles during embryogenesis and carbohydrate metabolism. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 52, 273–288 (2010).

Wang, X. et al. The BRANCHING ENZYME1 gene, encoding a glycoside hydrolase family 13 protein, is required for in vitro plant regeneration in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 117, 279–291 (2014).

Polowick, P. L., Baliski, D. S., Bock, C., Ray, H. & Georges, F. Over-expression of α-galactosidase in pea seeds to reduce raffinose oligosaccharide content. Botany 87, 526–532 (2009).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Mário Alfredo Passos Saraiva (Embrapa Cenargen, Brazil) for valuable contributions to the qRT-PCR experiments.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from EMBRAPA (Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation), INCT PlantStress Biotech (project number 465480/2014-4) and FAPDF (Distrito Federal Research Foundation; project number 0193.001565/2017). CCV, APZM, BNP and ALL received fellowships from CAPES (Brazilian Federal Agency for Support and Evaluation of Graduate Education) and CNPq (Brazilian National Council for Scientific and Technological Development). EGJD was supported by a visiting scientist grant from the Science without Boarders CNPq program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.C.V.: conceptualization; investigation; writing—original draft; writing—review & editing. A.P.Z.M.: formal analysis; writing—review & editing. B.N.P.: formal analysis; writing—original draft. T.N.O.: investigation. I.S.: investigation. A.L.L.: investigation. E.G.J.D.: methodology; writing—review & editing. P.M.G.: conceptualization; writing—review & editing; supervision; project administration; funding acquisition. T.C.R.W.: conceptualization; investigation; writing—review & editing. A.C.M.B.: conceptualization; writing—original draft; writing—review & editing; supervision; project administration; funding acquisition. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Vinson, C.C., Mota, A.P.Z., Porto, B.N. et al. Characterization of raffinose metabolism genes uncovers a wild Arachis galactinol synthase conferring tolerance to abiotic stresses. Sci Rep 10, 15258 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-72191-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-72191-4

This article is cited by

-

Spatio-temporal expression pattern of Raffinose Synthase genes determine the levels of Raffinose Family Oligosaccharides in peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) seed

Scientific Reports (2023)

-

Application of galactinol to tomato enhances tolerance to cold and heat stresses

Horticulture, Environment, and Biotechnology (2022)

-

Transcriptome Analysis of Different Sections of Rhizome in Polygonatum sibiricum Red. and Mining Putative Genes Participate in Polysaccharide Biosynthesis

Biochemical Genetics (2022)

-

Defining the combined stress response in wild Arachis

Scientific Reports (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.