Abstract

SQUAMOSA-promoter binding like proteins (SBPs/SPLs) are plant specific transcription factors targeted by miR156 and involved in various biological pathways, playing multi-faceted developmental roles. This gene family is not well characterized in Brachypodium. We identified a total of 18 SBP genes in B. distachyon genome. Phylogenetic analysis revealed that SBP gene family in Brachypodium expanded through large scale duplication. A total of 10 BdSBP genes were identified as targets of miR156. Transcript cleavage analysis of selected BdSBPs by miR156 confirmed their antagonistic connection. Alternative splicing was observed playing an important role in BdSBPs and miR156 interaction. Characterization of T-DNA Bdsbp9 mutant showed reduced plant growth and spike length, reflecting its involvement in the spike development. Expression of a majority of BdSBPs elevated during spikelet initiation. Specifically, BdSBP1 and BdSBP3 differentially expressed in response to vernalization. Differential transcript abundance of BdSBP1, BdSBP3, BdSBP8, BdSBP9, BdSBP14, BdSBP18 and BdSBP23 genes was observed during the spike development under high temperature. Co-expression network, protein–protein interaction and biological pathway analysis indicate that BdSBP genes mainly regulate transcription, hormone, RNA and transport pathways. Our work reveals the multi-layered control of SBP genes and demonstrates their association with spike development and temperature sensitivity in Brachypodium.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Characterization of various transcription factors has revealed their organism-specific function and a particular class of these transcription factors have been discovered in animals, yeast and plants. SQUAMOSA-promoter binding like proteins (SBPs) form a major family of plant-specific transcription factors. SBPs were first identified in Antirrhinum majus interacting with the promoter sequence of floral meristem gene SQUAMOSA1. SBP-box proteins share a highly conserved 76 amino-acids long DNA binding domain known as SBP domain, which contains two zinc ion binding motifs (Cys2HisCys and Cys3His) and a nuclear localization signal (NLS) sequence2. The SBP domain of the SBP-box family members binds to TNCGTACAA consensus sequence present in the promoter regions with GTAC as a core motif3,4. Phosphorylation of serine amino acid within the SBP domain has been recently shown to modify DNA binding affinity and immunity in rice5. As a multigene family, SBP genes have been identified in green moss6, algae7, P. trichocarpa8 and angiosperm9. There are 16 SBP genes in Arabidopsis thaliana10, 19 in rice11, 28 in Populus trichocarpa8, 41 in soybean12 and 17 in barley13. SBP genes play key roles in various plant developmental pathways such as flowering time14, vegetative to reproductive phase transition15,16, plant architecture17,18,19, gibberellic acid biosynthesis20,21, anthocyanin biosynthesis22, and abiotic stresses23,24.

Another layer of gene regulation involves microRNAs (miRNAs), which are single-stranded non-coding RNA molecules of 20–22 nucleotides in length that bind to their complementary sequences present in the messenger RNAs (mRNAs) of their target genes25,26. Thus, both miRNAs and their target genes can be manipulated for crop improvement. Out of 16 SBP genes in Arabidopsis, 10 are known to be negatively regulated by a conserved miRNA, miR15627. The role of SBP/miR156 module has been observed in many plant developmental processes such as, vegetative to reproductive phase change, plant architecture and flowering time14,18. On the basis of SBP domain, these genes can be classified into five groups in Arabidopsis such as SPL3/4/5, SPL9/15, SPL2/10/11, SPL6 and SPL13A/B6,11. The miR156 targeted SPLs accelerate the phase transition by positively regulating the expression of APETALA1 (AP1), FRUITFULL (FUL), and SUPPRESSOR OF CONSTANS OVEREXPRESSION 1 (SOC1) and LEAFY genes28,29,30. In wheat and barley, VERNALIZATION1 (VRN1) is the homolog of FUL/AP1 and acts as both an activator and a target of VRN3 which is a homolog of FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT)31,32,33. Based on the gain or loss of functions, SPL genes in Arabidopsis can be classified into three groups30. Group 1 contains SPL2/9/10/11/13/15 genes which promote both the juvenile-to-adult transition (vegetative phase) and the vegetative-to-reproductive phase transition. The SPL9/13/15 genes are central players for these developments as compared to SPL2/10/11. Group 2 contains SPL3/4/5 genes, which play major roles to accelerate the transition of floral meristem identity. Group 3 contains only SPL6 which does not have a major role in shoot development but may be key to some other biological pathways.

In monocots, SBP/miR156 module has been anticipated as an important tool-box to genetically enhance crop productivity34. Interaction between miR156-SPLs and strigolactone signaling pathway regulates bread wheat tiller branching and spikelet development35. In rice, overexpression of OsmiR156 targets OsSPL14 and promotes panicle branching and grain yield18,36. Likewise, miR156 regulated OsSPL16 and OsSPL13 control grain shape, size and quality in rice37,38. The unbranched2 and unbranched3 members of SBP-box transcription factor family modulate plant architecture and yield in maize39. In switchgrass, miR156/SPL4 module regulates aerial axillary bud formation; branching and biomass yield19.

Brachypodium distachyon, the small monocot plant, is an emerging model system ideal for functional genomics research to study complex monocot species, especially the triticeae crops40,41. It is extensively being used to study the biology of flowering and vernalization response42,43. In Arabidopsis, FLOWERING LOCUS T (FT) gene is known as a key player of floral signaling processes44. In Brachypodium, FT undergoes age dependent alternative splicing and is regulated by miR5200 and FT/miR5200 module control photoperiod dependent flowering45,46,47,48. Homoeolog-specific transcriptome changes under heat stress conditions have been examined in B. stacei, B. distachyon and B. hybridum49. Brachypodium auxin influx facilitator (AUX1) T-DNA mutants showed dwarf phenotype and had aberrant flower development50. In the current study, we identified 18 SBP genes in B. distachyon genome and studied their phylogenetic relationship with barley, wheat, rice and Arabidopsis. Further, their gene structure, alternative splicing event, gene duplication event, miR156 mediated negative regulation, co-expression and protein–protein interaction network have been investigated systematically. Transcriptional changes of individual SBP genes in leaf and spike at different developmental stages and temperature regimes were critically examined. Moreover, SBP genes role in early (Bd21) and late (Bd1-1) flowering accessions of Brachypodium was verified. Further, Bdsbp9 T-DNA mutant was characterized to understand its function in spike development.

Results

Identification and characterization of SBP-box genes in B. distachyon

In this study, we identified 18 SBP genes in B. distachyon and designated as BdSBP. BdSBP family members were named according to the closest homologs present in wheat, barley or rice. Details of SBP gene family in Brachypodium are given in Table 1. Brachypodium SBP genes encode proteins ranging from 177 (SPL7) to 1,110 (SPLl4) amino acids (aa) in length and from 122 kda (SBP15) to 12 kda (SBP23A) in molecular weight. The number of exons ranged from 1 to 11 and isoelectric point (pI) was from 5 to 10. The 18 BdSBP genes were located on all 5 chromosomes (chr), with maximum number of BdSBP genes detected in chr 3 of B. distachyon (Table 1).

Phylogenetic analysis and gene duplication in BdSBP genes

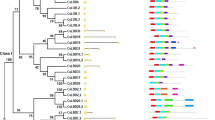

A phylogenetic tree was constructed using conserved SBP domain sequences of SBP proteins from Brachypodium, wheat, barley, rice and Arabidopsis (Fig. 1A,B). A total of 79 SBP proteins from different plant species including 18 from rice, 10 from wheat, 17 from barley and 16 from Arabidopsis were used for phylogenetic analysis. SBPs clustered into 8 groups (G1–G8), with AtSBP3/4/5/6 as ungrouped members. Each group contained at least one SBP protein from Brachypodium. As anticipated, BdSBPs exhibited closer relationship with the SBP proteins from barley and wheat as compared to rice and Arabidopsis. Group 1 and group 5 contained maximum number of BdSBPs, where SBP proteins from barley and wheat were also grouped. Moreover, gene duplication analysis among BdSBP genes identified 9 putative paralogous gene pairs in the Brachypodium genome (Fig. 2A,B). Divergence time for duplicated BdSBP genes was estimated from Ka and Ks values and their ratios. The dates of duplication events (T) were calculated using Ks values through the formula T = Ks/2λ × 10−6 (millions of year, Mya). The λ = 6.5 × 10−9 substitutions per synonymous site per year was assumed as universal clock-like rate for Brachypodium distachyon. For BdSBP1 and BdSBP6 gene pair, Ka and Ks values were 0.60 and 2.14, respectively and their ratios 0.28 imply their evolution under purifying selection. Similarly, the ratio (0.30) of Ka and Ks values for BdSBP16 and BdSBP18 gene pair highlights purifying selection. Purifying selection also called negative selection, influence genomic diversity in natural populations. It eliminates the changes that produce deleterious effects on the fitness of the host. The frequency distributions indicate that SBP genes in Brachypodium went through a large-scale duplication event ranging from 55 to 164 million years ago (mya). SBP gene paralogs were located on same as well as different chromosomes, indicating that expansion of Brachypodium SBP genes was both, tandem as well as segmental/block duplication during evolution.

taken from Brachypodium, barley, wheat, rice and Arabidopsis. The amino acid sequences were aligned using MUSCLE tool and Interative Tree of Life (iTOL) resource was used to annotate the phylogenetic tree. (B) Sequence logo of Brachypodium SBP domain. The height of amino acid residues shows level of conservation. Two zinc finger motif and nuclear localization signal (NLS) and joint peptide are shown.

Evolutionary analysis of SBP domain transcription factors. (A) Phylogenetic tree of SBP proteins

Gene duplication of SBP genes in Brachypodium genome. (A) Segmental and tandem duplications gene pairs located on Brachypodium chromosome regions are marked in red and green colours. The gray lines on each chromosome represent the total number of SBP genes present in Brachypodium genome. (B) Summary of BdSBP duplicated gene pairs and type of duplication events in Brachypodium.

BdSBP genes have diverse gene and protein structures

Gene structure and genetic diversity analyses (Fig. 3A–C) in Brachypodium SBP gene family revealed that the BdSBP genes contain at least one intron; however genes in group 1–3 have the largest number (10–11) of exons (Fig. 3A). Other BdSBP genes possess only 2–4 exons. Interestingly, five sister gene pairs (SBP1/6; SBP14/17; SBP21/22; SBP3/11 and SBP16/18) have similar exon/intron numbers but intron phases with variable lengths. Conserved motif sequence database search identified a total of 10 motifs, which were designated as motif 1–10 (Fig. 3B). Gene pairs (SBP1/6/15; SBP14/17; SBP8/21/22 and SBP16/18) shared a similar type of motif structure. Some motifs were found to be specific to one or two groups of BdSBP proteins. Motif 6 that encodes miR156 target sequence was present in all miR156 targeted BdSBP proteins. Whereas motif 10 and motif 4 were found in group 1 BdSBP and group 3 and 4 BdSBP proteins respectively. To predict possible functions of BdSBP genes, we also performed gene ontology (GO) term enrichment analysis (Fig. 3C). Most of the BdSBP genes with similar gene structure and motifs (BdSBP1/6; BdSBP3/11; BdSBP13A/23A; BdSBP14/17; and BdSBP16/18) were predicted for their similar biological processes (BP), molecular function (MF) and cellular component (CC).

Gene structure and protein motif analysis of BdSBP genes. (A) Un-rooted neighbour-joining tree was developed using SBP domain sequences through MEGA6 package. The organizations of exon–intron and intron phases of the BdSBP genes are displayed. Exons, introns and 5′UTR/3′UTR are denoted by red boxes, horizontal black lines and black boxes, respectively. *miR156 targeted BdSBP genes. (B) The conserved motifs in BdSBP proteins are shown in different colors. Full length protein sequences of BdSBPs were used to search motif using MEME tool. (C) Functions of BdSBP genes are annotated based on Gene ontology. The biological processes (BP), molecular functions (MF), and cellular component (CC) are shown in the box below. Biological Processes (BP): 1. GO:0006355; regulation of transcription, DNA-templated; 2. GO:0010229;inflorescence development; 3. GO:0010228;vegetative to reproductive phase transition of meristem; 4. GO:0010321;regulation of vegetative phase change; 5. GO:0009911;positive regulation of flower development; 6. GO:0055070;copper ion homeostasis; 7. GO:0048638;regulation of developmental growth; 8. GO:0035874;cellular response to copper ion starvation; 9. GO:0048510;regulation of timing of transition from vegetative to reproductive phase; 10. GO:0048653;anther development; 11. GO:0045893;positive regulation of transcription, DNA-templated 12. GO:0010358;leaf shaping 13. GO:0009556;microsporogenesis; 14. GO:0009554;megasporogenesis; 15. GO:0042127;regulation of cell proliferation; 16. GO:2000025;regulation of leaf formation; 17. GO:0008361;regulation of cell size;18. GO:0042742;defense response to bacterium; 19. Unknown (U). Molecular function (MF): 1.GO:0003677; DNA binding; 2. GO:0005515;protein binding; 3. GO:0003700; transcription factor activity, sequence-specific DNA binding; 3. GO:0043565; sequence-specific DNA binding; 4. GO:0042803;protein homodimerization activity; 5. GO:0044212; transcription regulatory region DNA binding; 6. unknown (U). Cellular Component (CC): 1. GO:0005634;Nucleus; 2. GO:0009941;chloroplast envelope 3. GO:0016607;nuclear speck; 4. GO:0005886;plasma membrane 5. Unknown (U).

Higher transcript abundance of BdSBP genes correlates with early inflorescence development

RNA-seq data of B. distachyon acc. Bd21(https://www.ebi.ac.uk/gxa/experiments/E-MTAB-4401/Results) from 9 different tissues and organs (leaf, early inflorescence, emerging inflorescence, anther, pistil, seed 5 days after pollination, seed 10 days after pollination, plant embryo and endosperm) was mined to understand the dynamics of BdSBP genes expression (Fig. 4). The expression profile of BdSBPs was grouped into three clusters. Higher expression of BdSBP genes of cluster 1 was observed in early inflorescence, emerging inflorescence and pistil tissues. Many BdSBP genes of cluster 1 were also expressed in anther, plant embryo, developing seeds (5 and 10 days after pollination), leaf, and endosperm tissues, implying their significant role throughout the Brachypodium plant development, especially in spike architecture. The BdSBP genes of cluster 2 (BdSBP7 and BdSBP1) either lacked expression in any tissue (BdSBP7) or poorly expressed (BdSBP1) in pistil, leaf, and developing seeds (seed 5 and 10 days after pollination), and endosperm. The BdSBP genes from cluster 3 were found to be expressed mainly in early and emerging inflorescence. Expression profiles of BdSBP genes indicate their involvement in the reproductive units of B. distachyon.

Expression pattern of BdSBP genes in nine different tissues. The log2 transformed FPKM values are represented as a color scale bar on the top of heatmap which shows high and low expression. Details of tissues utilized for expression analysis are shown on the top of map. The genes are mentioned on the right side of the map and *denotes miR156 targeted BdSBPs.

Post-transcription of BdSBP genes is regulated by miR156 and alternative splicing (AS)

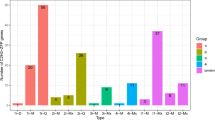

The cDNA sequences of BdSBP genes were searched for putative target sites of Brachypodium miRNAs (Fig. 5A). Ten BdSBP genes are found to be the target of miR156. Out of these, 8 contain miR156 complementary sequences in their coding regions. However, in other two genes, BdSBP1 and BdSBP13, miR156 target site was found in their 3′-UTR and 5′-UTR regions, respectively. The BdSBP gene family undergoes AS which specifically targets miR156 regulated BdSBP (Fig. 5B). The number of splice isoforms for each BdSBP genes was derived from plant Ensembl database. Splice variants from Ensembl gene are compared to generate an inclusive list of elementary alternative splicing events. The range of splice isoforms produced by BdSBPs was between 2 and 7. Most of the splice variants of BdSBP genes possess miR156 target site except BdSBP1, which has 4 splice variants and only one contains miR156 target site.

Analysis of post-transcriptional regulation of BdSBP genes by miR156 and AS. (A) Prediction of miR156 target site in BdSBPs transcripts. The SBP domain is represented in green. miR156 complementary sequences of BdSBPs are indicated in red. 5′ and 3′-UTRs are indicated in black horizontal lines. (B) Details of AS events in miR156 targeted and non-targeted BdSBP genes. X-axis shows BdSBP genes and Y-axis indicates number of transcripts. (C) Agarose gel image showing product of 5′-RACE PCR to measure transcript cleavage of BdSBP genes by miR156. (D) miR156 mediated cleavage site mapping in BdSBP3, BdSBP17 and BdSBP23 genes. The arrow indicates exact cleavage site and number indicates clones used for confirmation. (E) Semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis of BdSBP genes in leaf and spike tissues. BdUBC18 was used as an internal control. miR156 targeted BdSBP genes expressed poorly in leaf and higher in spike.

Organ specific differential accumulation of BdSBP genes is regulated by miR156

Three BdSBP genes (BdSBP3, BdSBP17 and BdSBP23) were analyzed for miR156 mediated transcript degradation by 5′-RLM-RACE (Fig. 5C,D). Additionally, to observe miR156 mediated cleavage pattern, we also constructed cDNA libraries from leaf and spike. Interestingly, BdSBP genes were highly degraded by miR156 in leaf as compared to spike tissue. We hypothesized that this differential degradation of BdSBP genes in leaf and spike tissues might be connected with their expression patterns in these tissues. To validate this, we performed semi-quantitative RT-PCR of several potential BdSBP genes on the basis of in silico expression data (Fig. 5E). Our data indicate that miR156 targeted BdSBP genes indeed expressed poorly in the leaf and abundantly in the spike, confirming our hypothesis. The miR156 non-targeted genes (BdSBP9 and BdSBP15) expression was constant in both the leaf and the spike, suggesting no effect of miR156 on these genes. Furthermore, to map the miR156 cleavage site in BdSBPs transcript, the 5′-RLM-RACE products were cloned and sequenced. Data indicates that miR156 cleaves between 9 and 10th nucleotide of 5′ site of BdSBPs transcript, except BdSBP3 where cleavage site was found between 10 and 11th nucleotides. Collectively, our results suggest multilayered regulation of BdSBP genes at the post-transcriptional level.

BdSBP genes are involved in complex regulatory network and pathways

BdSBPs co-expressed genes were investigated using publicly available large-scale co-expression database (www.gene2function.de), and MapMan (https://mapman.gabipd.org) ontology term enrichment to study their roles in different biological pathways (Fig. 6A–B). Around 710 co-expressed genes were found to be associated with 15 members of BdSBP family (Supplementary Table S5). The MapMan ontology of the co-expressed genes suggests that 22 out of 35 of the major biological classes have at least one of the BdSBP family members (Fig. 6B). Cell, development, transport, hormone metabolism, secondary metabolism, stress, lipid metabolism, cell wall, DNA, RNA, protein and signaling were major biological processes in which co-expressed genes of BdSBP family members were involved. Some other BdSBP family members and their co-expressed genes were enriched in photosynthesis, major CHO metabolism, fermentation, oxidative pentose pathway, mitochondrial electron transport and amino acid metabolism. However, BdSBP co-expressed genes were not augmented in the C1-metabolism, microRNA, polyamine metabolism, nucleotide metabolism, S-assimilation, N-metabolism, glycolysis and minor CHO metabolic pathways.

Co-expression and metabolic pathway analysis of BdSBP genes: (A) the co-expression neighbourhood was analysed using PlaNet tool. The green, oranges and red edge colours shows strong, medium and weak co-expression. Coloured shapes indicate label co-occurrences. The gene annotation of co-expressed genes is available in Supplementary Table S5. (B) The co-expressed genes of BdSBPs that are enriched for a biological pathway given by MapMan term are shown by red boxes.

In addition, a network of protein–protein interaction of B. distachyon proteins was developed using STRING database. This database predicts interactions based on experimentally determined, predicted, text mining, co-expression, gene fusion, gene neighbourhood etc. A total of 39 interactive proteins were found (confidence value = 0.5) for 9 of BdSBP proteins, which were based on either predicted interactions or text mining (Fig. 7A, Supplementary Table S6). Protein annotation reveals that BdSBP proteins might interact with MYB33, PHABULOSA (PHB), Homeobox TF family, Growth regulating factor 5 (GRF5), Heat shock TF, ZnF C2H2, F-box TF, NBS-LRR, protein kinase family protein, ankyrin repeat protein, protein kinase family protein, chlorophyll a-b binding protein, DCL1, DCL2 and DCL3 proteins. The BdSBP7 was the only B. distachyon protein that interacts with DCL2 and DCL3 proteins. The MapMan term ontology of interactive protein partners of the BdSBPs indicates that 10 out of 35 proteins of the major biological terms were enriched by at least one of the BdSBP protein network (Fig. 7B). These biological processes were linked to development, RNA, photosynthesis, cell wall, protein, transport, signaling, cell cycle and stress.

Protein interaction network and pathway analysis of BdSBP proteins. (A) The potential interactors for 9 BdSBP proteins were predicted using STRING tool and are shown with different coloured connective lines. (B) The biological pathways enriched in MapMan terms in which the interacting partners of BdSBP proteins are involved. (C) Effect of heat stress on the expression of BdSBP genes in B. distachyon, B. stacei, and B. hybridum grown under normal (22 °C) and heat stress (42 °C) conditions.

BdSBP genes express differentially during variable temperature conditions

In order to advance our knowledge about the molecular mechanism controlling heat stress in Brachypodium, we examined the transcriptional changes in BdSBP genes in the spike development under 22 °C and 42 °C in B. distachyon, B. stacei and B. hybridum (Fig. 7C). Transcript abundance of BdSBP1, BdSBP14 and BdSBP16 was higher at 42 °C among all the accessions, independent of ploidy level and it will be important to functionally validate these key genes in future. Negligible transcript abundance of BdSBP8, BdSBP9 and BdSBP23 was observed in B. stacei. However, transcript level of BdSBP3, BdSBP8, BdSBP9, BdSBP18 and BdSBP23 was higher in B. distachyon and B. hybridum as compared to B. stacei under both conditions. We did not observe any temperature dependent specific expression pattern among miR156 targeted and non-targeted BdSBP genes. Our results imply important roles of BdSBP genes to beat the heat in the reproductive organs of Brachypodium spp.

BdSBP genes regulate spike development and flowering

In silico expression analysis revealed higher expression of BdSBP genes during spike emergence and in early inflorescence development (Fig. 4). Therefore, the transcript abundance of 9 BdSBPs was examined during different developmental stages [7–24 Days after Heading (DAH) of Brachypodium spikelet] (Fig. 8A,B; Supplementary Fig. S3). Five genes including BdSBP3, BdSBP16, BdSBP17, BdSBP18, BdSBP21 and BdSBP23 were highly abundant during early spikelet development (7 DAH), as compared to mid-phase (15–20 DAH) or maturation phase (24 DAH). However, the transcript level of BdSBP1 was constant at 7, 15 and 20 DAHs except at 24 DAH. No change in transcript level of BdSBP15 was observed at any of the above-mentioned developmental stages. Expression pattern of BdSBP9/16/17/18 was also confirmed by qPCR (Fig. 8B). Expression of BdSBP9 was slightly lower at 15DAH as compared to 7 and 24DAHs.

Expression pattern of BdSBP genes during spikelet development and flowering. (A,B) Semi-quantitative RT-PCR and quantitative real time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis of BdSBP genes at 7, 14, 20, and 24 DAH stages of spikelet development. *miR156 targeted BdSBP genes. (C) Brachypodium accessions Bd21 (early flowering) and Bd1-1 (delayed flowering) under vernalization and non-vernalization time course. Bar represents 1 cm. (D) Semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis of BdSBP genes in vernalized and non-vernalized Brachypodium accessions Bd21 and Bd1-1. BdUBC18 was loaded as internal control.

To ensure the reproductive success, flowering is the critical stage of plant reproduction, which is mainly regulated by gibberellin, vernalization, photoperiod and autonomous pathways. Vernalization promotes the flowering in alpine species and its molecular mechanism has been investigated in Arabis alpina and A. thaliana plants (Bergonzi et al.51). Therefore, to understand the genetic control of vernalization response in grasses, we analysed the expression pattern of BdSBP genes in Brachypodium. Transcript abundance of several BdSBP genes was compared in the rapid flowering (Bd21) and delayed flowering (Bd1-1) accessions of Brachypodium under vernalization and non-vernalization conditions (Fig. 8C,D; Supplementary Fig. S4). We observed that Bd21 accession flowered rapidly under non-vernalised condition, whereas Bd1-1 lacked flowering until maturity. However, both the accessions produced flowers with 6-weeks vernalisation at 4 °C. BdSBP1 and BdSBP3 expressed differentially in these accessions following vernalization or non-vernalization. The expression of BdSBP1 and BdSBP3 were found to be lower in Bd1-1 as compared to Bd21 under non-vernalized condition. Whereas, under vernalized condition, no change in the transcript level was observed suggesting their possible role in flowering time and spikelet development. However, transcript level of BdSBP9/16/17/21/23 was not altered significantly under vernalization condition.

To further confirm the function, T-DNA mutant for BdSBP9 gene was obtained from JGI (Fig. 9A–C). The Bdsbp9 mutant has a T-DNA insertion in the first exon of BdSBP9. Electron microscopy indicated that different patterns of lignification in the wild type as compared to Bdsbp9. Wild-type patterns were straighter, with no circular patches whereas, Bdsbp9 patterns are less uniform, with some circular patches. Further, we investigated the promoter region (1000 bp upstream of initiation codon) of the co-expressed genes of BdSBP9 (Fig. 9D). Data indicate that 92% of the co-expressed genes contain GTAC motif, a specific binding site for SBP genes. The expression of one of the interacting partners matches with BdSBP9 expression pattern (Fig. 9E).

Shoot and spikelet phenotype of Bdsbp9 mutant. (A) Schematic diagram of the T-DNA insertion line for BdSBP9 gene. The insertion was within first exon of the gene. (B) Comparison of shoot growth in Bd21-3 wild-type and Bdsbp9 mutant at vegetative and reproductive stage. Bar represents 1 cm. (C) Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis of the terminal spikelet of Bd21-3 wild-type and Bdsbp9 mutant. The SEM was performed at three resolutions at ×25, ×100 and ×500. Bar represents 4 mm, 1 mm and 200 µm. (D) Promoter regions analysis of BdSBP9 co-expressed genes for GTAC binding motif. (E) Heat map based expression analysis of BdSBP9 interactor proteins.

Discussion

SBP/miR156 genetic circuit controls the transition of vegetative to reproductive phase change in Arabidopsis14,52. Owing to the importance of SBP genes, we conducted the first-ever genome-wide identification of this gene family in Brachypodium and discovered 18 BdSBP genes (Table 1). The number of SBP genes in Brachypodium were similar to the SBP genes in barley (17), B. luminifera (18), rice (19) and Arabidopsis (17), but was smaller in comparison to soybean (41), moso bamboo (32) and P. trichocarpa (28), suggesting that SBP genes were evolved in a species specific manner and underwent different gene duplication events. On the basis of phylogenetic analysis BdSBP genes were divided into eight (G1–G8) groups (Fig. 1A). BdSBP genes grouped closely with HvSPLs and TaSPLs, suggesting that these SBP genes possibly diverged from a common ancestor. The DNA binding SBP domain binds to the promoter regions of its target genes containing TNCGTACAA consensus nucleotide sequence with GTAC as a core motif53. Two zinc ion binding motifs Cys3His1 and Cys2His1Cys1 at N terminus and a nuclear localization signal (NLS) at C terminus were found in BdSBP proteins (Fig. 1B). SBP genes share similar gene structures within their same phylogenetic group as mentioned previously in barley13, rice11,54, and tomato55. Gene duplication events are key to evolution and gene expansion which produce many paralogous gene pairs56. Additionally, gene duplication also assists organisms to cope up with different environmental conditions during growth and development57. In order to study gene duplication, we estimated the Ka/Ks ratio for each duplicated genes using Plant Genome Duplication Database and PLAZA 4.0 (Fig. 2A,B), which suggests that BdSBP genes underwent duplication event ~ 74 to 164 mya. The Ka/Ks ratio of > 1 shows that the gene has experienced positive selection, = 1 indicate neutral selection and < 1 indicates purifying selection or negative, respectively. Based on Ka/Ks ratio56; the BdSBP gene pairs which were ranged from 0.2 to 0.7 suggesting that these genes were duplicated under purifying selection. Also, BdSBP genes shared similar intron/exon structures within the same phylogenetic groups (Fig. 3A). Additionally, most of the BdSBPs from the same phylogenetic groups possess similar motifs (Fig. 3B). Consequently, the genes in the same phylogenetic group might have similar roles in Brachypodium, which have been supported by gene ontology terms of BdSBP genes (Fig. 3C). In addition to conserved BdSBPs motifs, several unique group-specific motifs were observed, such as motif 4, 9 and 10 in group 1 and motif 8 in group 8. These specific motifs might be important for specified roles of BdSBP genes, and their functional differentiation could arise during evolution of different lineages.

All BdSBP genes expressed substantially during early and emerging inflorescence development except, BdSBP1 and BdSBP7, implying their role in inflorescence development of Brachypodium (Fig. 4). Most of the BdSBP genes except, BdSBP7/8/17/21, expressed significantly in pistil whereas BdSBP3/6/11/ 14/15/16 expressed highly in the anther, suggesting their role during reproduction. However, BdSBP6/9/15 were constitutively expressed in all the 9 tissues. Previously, differences in expression profiles of miR156 targeted and non-targeted SBP genes have been reported in barley13, Brassica napus58, Betula59 and soybean12. Importantly, miR156 targeted BdSBP genes showed differential expression pattern and most of the miR156 non-targeted BdSBPs showed constitutive expression profiles in Brachypodium. Post-transcriptional regulation of SBP genes through miR156 has been considered as the key process for the functionality of these genes27,29,60. A total, 11 of 19 SBP genes in rice11, 10 of 17 SBPs in Arabidopsis52, 7 of 17 SBPs in barley13, and 18 of 28 SBPs in Populus8 have been identified as targets of miR156. In our study, miRNA target prediction revealed that 10 BdSBP genes are regulated by miR156 (Fig. 5A). A total 8 (BdSBP3,-11,-13A,-14,-16,-17,-18, and 23) of 10 miR156 targeted BdSBP genes contained miR156 complementary sequence in their coding region whereas, BdSBP1 and BdSBP13 contained target site in 5′ and 3′UTRs, respectively. Thus, miR156 targets BdSBP1 and BdSBP13 along with other BdSBP genes will be unable to perform downstream roles. This phenomenon of binding of miRNAs to their complementary sequences in the coding sequences or un-translated regions of target genes to inhibit gene function either by transcript cleavage or deadenylating has also been reported elsewhere (Rhoades et al.61).

In humans ~ 95% and in Arabidopsis > 60% of multi-exonic genes undergo AS62. Meanwhile, we noticed that miR156 targeted BdSBP genes produced different splice variants via. AS (Fig. 5B). AS generally produces transcripts with premature stop codon which are degraded in cytoplasm by non-sense-mediated decay (NMD) pathway63. Splice variants produced by AS generally exhibit spatiotemporal or environmental condition-specific expression patterns63. Our experiments in Brachypodium showed that BdSBP gene products are degraded at higher level by miR156 in the leaf as compared to the spike (Fig. 5C,D), resulting into higher transcript abundance of miR156 targeted BdSBP genes in young spike as compared to leaf (Fig. 5E; Supplementary Fig. S1). However, expression of miR156 non-targeted BdSBP9 and BdSBP15 genes was constitutive in these tissues. This confirms that miR156 negatively regulates SBP genes in Brachypodium and is consistent with previous findings in Arabidopsis, rice, tomato and wheat11,29,35,52,64. Taken together, these results suggest that miR156 in conjunction with AS regulates the transcriptome dynamics.

SBP-correlated gene network and interactome analysis revealed that SBP genes function by regulating other families of transcription factors and membrane transport proteins, and are involved in the metabolism of glucose, in-organic salts and ATP production in Arabidopsis65. Therefore, considering the significance of Brachypodium as a model plant for developmental biology of triticeae crops, we examined the co-expression and MapMan biological pathways (Fig. 6A,B; Supplementary Table S5). MapMan terms enrichment analysis showed that BdSBP genes perform their function by regulating transcription, protein, signalling, transport and development related biological pathways (Fig. 6B). The co-expression network contains mainly transcription factors, hormones (auxin, brassinosteroid, ethylene and gibberellin) responsive genes, cell wall biogenesis related genes and transporters, implying their roles in development as well as cell wall biogenesis of Brachypodium. Existence of CSLF3 and MYB TF indicate that BdSBP genes might be involved in secondary wall synthesis in Brachypodium66. Studying the protein–protein interaction network represents gene functions crucial to plant physiology, pathology, and growth67. Protein–protein interaction at the molecular level might be important in transcription regulation, post-transcriptional modification, cytoskeleton assembly, phosphorylation, acetylation, transporter activation and others68. Previously, it was found that IPA1 (OsSPL14), an important factor which controls plant architecture interacts with D53 protein (DWARF53) in-vivo and in-vitro69. Recently, OsSPL14 protein has been shown to be associated with disease and yield in rice by phosphorylation and non-phosphorylation of Ser163 amino acid respectively during Magnaporthe oryzae fungal infection5. In our study 39 interacting proteins with 9 BdSBP proteins were identified (Fig. 7A,B; Supplementary Table S6). These interacting proteins mainly belonged to bZIP, Homeobox, MYB33, ZnF_C2H2, F-box and heat shock transcription factor families, Dicer-like proteins and protein kinases. These interacting protein partners have been involved in the regulation of the biological pathways including development, RNA, protein, stress, photosynthesis and cell wall, implying the diverse roles of BdSBP proteins in Brachypodium growth and development.

The grain development and filling of Brachypodium spikelet are completed (dry) in 50 days and has been classified into three stages namely-embryo and endosperm development [0–14 days after fertilization (DAF)]; maturation (14–36 DAF) and desiccation (36–50 DAF) stages70. Higher expression of BdSBP1/-3/-16/-17/-18/-21 and 23 at spikelet initiation stage as compared to the maturation stage, might be key to early spikelet development in Brachypodium (Fig. 8A,B). Further, BdSBP9 and BdSBP15 genes exhibited constitutive expression pattern during embryogenesis and maturation stages, suggesting their importance for these stages. Plants bear flowers at a certain time of reproductive phase which is mainly regulated by SBP/miR156 pathway29. As plants grow older, the level of SBP genes increases while miR156 abundance declines. Previously, it was reported that higher production of SBP genes ensures flowering in response to cold in the model perennial Arabis alpina accession Pajares51. It has been reported in Cardamine flexuosa that SBP/miR156 pathway plays a key role in flowering through integrating age and vernalization pathway 71. The SPL/miR156 module has been known to be a key component for flowering phases1,52. Involvement of SBP genes in the control of flowering time of B. distachyon accessions Bd21 and Bd1-1 under vernalization condition (Fig. 8C,D) suggest that BdSBP1 and BdSBP3 potentially involved in this. This result positively supports the previous study about sensitivity of certain SBP genes to vernalization in older plants51. Cereals inflorescence (spike) architecture is one of the main determinants of their yield. In rice, SBP genes have been reported as an important regulator of plant architecture. Overexpression of OsSPL14, present on the IPA1 (ideal plant architecture)/WFP (wealthy farmer’s panicle) QTL, decreased tiller branching but increased panicle branching and grain weight18,36. Likewise, OsSPL7, OsSPL13 OsSPL16 and OsSPL17 also regulate grain size, shape and yield in rice16,37,38. In our study, the Bdsbp9 mutant showed abnormal spike and delayed flowering, implying its role in spike development (Fig. 9A–E). In Arabidopsis, miR156/SPL module confers thermotolerance at reproductive stage[24,72). Our study also indicates that BdSBP genes contribute thermotolerance during spike development in Brachypodium. Interestingly, differential expression of BdSBP genes in the developing spike under variable temperatures was not been associated with ploidy level in Brachypodium genome as described previously49. However, specific expression of these genes in response to high temperature in tetraploid genome, B. hybridum, probably induced by interaction of B. distachyon and B. stacei genomes (Fig. 7C; Supplementary Fig. S2). Overall, our study revealed that altering the expression pattern of BdSBP genes may provide an important tool-box for the genetic improvement of the cereal crops.

Materials and methods

Identification and annotation of SBP genes in Brachypodiumdistachyon

To identify SBP genes in Brachypodium distachyon genome, pHMMER search was performed on EnsemblPlants database (https://plants.ensembl.org/Brachypodium_di/Info/Index) using A. thaliana SBP domain (Pfam: PF03110) sequence as the query13,73. Additionally, phytozome (https://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov/pz/portal.html#!info?alias=Org_Bdiulgare_er) database was also mined through TBLASTN using SBP domain amino acid sequences. The accession numbers of putative BdSBP genes were taken from databases and were named based on their closest homologs present in barley, wheat and rice. Further, EnsemblPlants database (https://plants.ensembl.org/Brachypodium_di/Info/Index) was used to obtain the genomic sequences (Table S1), coding sequences (Supplementary Table S2) and protein sequences (Supplementary Table S3) of BdSBP genes.

Gene structure and phylogenetic analysis of BdSBP genes

The exon/intron structure of each BdSBP gene was predicted through gene structure display server program (https://gsds.cbi.pku.edu.cn/index.php) by comparing their coding and genomic sequences. The TAIR (https://www.arabidopsis.org/index.jsp) was used to obtain the Arabidopsis SBP sequences and rice genome annotation project database was used to obtain the rice SBP genes sequences. SBP sequences of wheat were obtained from a previous study74. SMART tool was used to identify SBP domain sequences from Brachypodium, rice, wheat, and A. thaliana which are presented in Supplementary Table S4. A phylogenetic tree was annotated using the Interactive Tree of Life resource (https://itol.embl.de). SBP domain sequences were aligned using MUSCLE tool followed by Gblocks curation utilities and maximum likelihood method was used to construct the phylogenetic tree using PhyML software (https://www.phylogeny.fr).

Motif identification, miR156 target site prediction and alternative splicing event analysis

The MEME 4.11.0 tool (https://meme-suite.org/tools/meme;) was used to search for conserved motifs within BdSBP proteins by using default settings, except that the maximum number of motifs to find was 10, the maximum width was 50 and the minimum width was 6. The sequence logo of the Brachypodium SBP domain was created with an online available WebLogo3 platform (https://weblogo.threeplusone.com/). The cDNA sequences of BdSBPs were subjected to psRNATarget tool (https://plantgrn.noble.org/psRNATarget/?function) to predict the putative target sites of miR156. The Ensemble database (https://plants.ensembl.org/Brachypodium_distachyon/Info/Index) was used to obtain the information on alternative splice events for each BdSBP gene (Supplementary Table S5).

Gene expression analysis of BdSBPs

The log2-transformed fragments per kilobase per million fragments measured (FPKM) values were used to study the expression of BdSBPs in nine tissues as described13,74. A heat map of the expression of BdSBPs was generated by the average hierarchical clustering method using the MeV tool (https://www.tm4.org/mev.html).

Co-expression, protein–protein interaction and gene duplication analysis

The co-expressed genes for BdSBP members were identified using online PlaNet (https://aranet.mpimp-golm.mpg.de/index.html) tool76. PlaNet uses the Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC) and constructs a co-expression network, with PCC cut-off to 0.777. Further, a highest reciprocal rank (HRR) co-expression network with standard edge cutoff of 30 was used. Additionally, a heuristic cluster chiseling algorithm (HCCA), which is optimized for HRRbased networks was used with standard parameters (stepsize = 3). The protein–protein interaction network was identified using STRING database (https://stringdb.org/cgi/input.pl?sessionId=A92xEG08sQEk&input_page_show_search=on), which contained information from various datasets such as; gene coexistence, protein–protein interactions, gene fusion and co-expressed genes to calculate the semantic links between proteins78. The genome-wide genomic duplication files of B. distachyon were retrieved from the plant genome duplication database (PGDD) (https://chibba.agtec.uga.edu/duplication) and PLAZA4.0 (https://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/plaza/versions/plaza_v4_dicots/,79. s*The synonymous substitution (Ks) and non-synonymous substitution (Ka) rates were obtained from PGDD and the ratios of Ka/Ks were used to assess the selection pressure for duplicated gene events.

Plant material and sample preparation

Brachypodium seeds from Bd21-3, Bd21, B. hybridum, B. stacei and Bd1-1 accessions were obtained from Prof. John Vogel (DOE Joint Genome Institute, CA, 94598 USA). Seeds were imbibed in water overnight, dried and stratified at 4 °C in the dark for 1 week. The daily temperature was 22 °C and the photoperiod was 16-h-light/8-h-dark (long day). The Bdsbp9 mutant line JJ12467 was obtained from a Brachypodium T-DNA insertion library80; Prof. John Vogel’s lab; JGI). The T3 Bdsbp9-mutant seeds were advanced for two further generations using conditions described above and according to method by81. For the vernalization experiment, Bd21 and Bd1-1 seeds were vernalized for 6 weeks at 4 °C. For heat stress study, B. distachyon, B.hybridum and B. stacei seeds were grown under 22 °C and 42 °C for 2 h. Further, immature spikes were collected from each accession to elucidate transcript abundance of BdSBP genes. To study the expression pattern of BdSBP genes in Brachypodium spike development, tissue samples were collected from leaf, and spike tissue at 7, 14, 21, and 25 days after heading (DAH).

Genomic DNA and RNA isolation

Leaves from Brachypodium distachyon plants were collected and DNA isolation was performed using cetyl-trimethyl-ammonium bromide-based (CTAB) extraction method as described elsewhere82. PCR-based genotyping was performed using primers following recommendations from Joint Genome Institute80. The spectrum plant total RNA Kit (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was used for RNA isolation following the manufacturer’s protocol. The RNA integrity and purity of all samples were verified on a Nanodrop ND-1000 (Nanodrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA). Prior to synthesizing cDNA, RNA samples were treated with DNase I to remove genomic DNA contamination (Invitrogen, USA). The reaction mixtures were incubated at 23 °C for 15 min and after that 1 µl of 25 mM EDTA was added to each sample.

First strand cDNA synthesis and quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis

First strand cDNA was synthesized from 2 µg total RNA sample using AffinityScript QPCR cDNA Synthesis Kit (Agilent technology, Canada). The qRT-PCR was run on Mx30005p qPCR system (Stratagene, USA) in a 20-μl volume containing 5 µM gene-specific primers, 1 μl diluted cDNA, and 10 μl Brilliant III Ultra-Fast SYBR Green QPCR Master Mix (Agilent, USA). Two biological and three technical replicates were used in all the experiments. The 2−ΔΔCq method was used to quantify the relative level of gene expression (Livak and Schmittgen 2001). The gene-specific primers for BdSBP genes used in semi-quantitative RT-PCR and qRT-PCR are listed in Supplementary Table S7. PCR was performed in a 20 μl volume using GoTaq Green master mix (Promega, USA). BdUBC18 (Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme 18) was used as a reference gene for different developmental stages and SamDC (S-adenosyl methionine decarboxylase) was used for heat stress83.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

Immature spikes (14 days after anthesis) were collected from Bdsbp9-mutant and control plants. Samples were fixed in 25 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) with 3% glutaraldehyde overnight. Dehydration of the tissue was carried out by increasing the ethanol concentration of the solution every hour (30%, 40%, 50%, 60%, 75%, 90%, 100%), keeping the samples in 100% ethanol for two days. Samples were critically point dried using the Leica EM CPD300 and coated with platinum using the Leica EM ACE200. The samples were visualized using Hitachi TM1000.

RNA ligase-mediated modified 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RLM-RACE)

The miR156 mediated cleavage site in the BdSBP transcript was mapped by using First-choice RLM-RACE kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). Total RNA was isolated from leaf and 7 days old spike (after heading). Without pre-treatment, 1 μg total RNA was ligated to the 5′ RACE RNA adapters. The M-MLV reverse transcriptase enzyme and 18mer oligo dT were used to reverse transcribe the adapter-ligated RNA. Primary and secondary nested PCR was carried out using 5′ RACE gene-specific outer and 5′-adapter outer primers and 5′ RACE gene-specific inner and 5′-adapter inner primers. The primer sequences used in nested PCR are listed in Supplementary Table S5. The 5′ RACE PCR amplified fragments were gel extracted and cloned into pGEMTeasy vector. Further, clones were confirmed by EcoRI restriction analysis and Sanger sequencing.

Abbreviations

- SBP:

-

SQUAMOSA-Promoter binding like transcription factor

- miR156:

-

MicroRNA156

- qRT-PCR:

-

Quantitative real-time PCR

- WT:

-

Wild type

References

Klein, J., Saedler, H. & Huijser, P. A new family of DNA binding proteins includes putative transcriptional regulators of theAntirrhinum majus floral meristem identity geneSQUAMOSA. Mol. Gener. Genet. 250, 7–16 (1996).

Yamasaki, K. et al. A novel zinc-binding motif revealed by solution structures of DNA-binding domains of Arabidopsis SBP-family transcription factors. J. Mol. Biol. 337, 49–63 (2004).

Birkenbihl, R. P., Jach, G., Saedler, H. & Huijser, P. Functional dissection of the plant-specific SBP-domain: Overlap of the DNA-binding and nuclear localization domains. J. Mol. Biol. 352, 585–596 (2005).

Kropat, J. et al. A regulator of nutritional copper signaling in Chlamydomonas is an SBP domain protein that recognizes the GTAC core of copper response element. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102, 18730–18735 (2005).

Wang, J. et al. A single transcription factor promotes both yield and immunity in rice. Science 361, 1026–1028. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aat7675 (2018).

Riese, M., Hahmann, S., Saedler, H., Münster, T. & Huijser, P. Comparative analysis of the SBP-box gene families in P. patens and seed plants. Gene 401, 28–37 (2007).

Guo, A.-Y. et al. Genome-wide identification and evolutionary analysis of the plant specific SBP-box transcription factor family. Gene 418, 1–8 (2008).

Li, C. & Lu, S. Molecular characterization of the SPL gene family in Populus trichocarpa. BMC Plant Biol. 14, 131 (2014).

Zhang, S.-D., Ling, L.-Z. & Yi, T.-S. Evolution and divergence of SBP-box genes in land plants. BMC Genom. 16, 787 (2015).

Cardon, G. et al. Molecular characterisation of the Arabidopsis SBP-box genes. Gene 237, 91–104 (1999).

Xie, K., Wu, C. & Xiong, L. Genomic organization, differential expression, and interaction of SQUAMOSA promoter-binding-like transcription factors and microRNA156 in rice. Plant Physiol. 142, 280–293 (2006).

Tripathi, R. K., Goel, R., Kumari, S. & Dahuja, A. Genomic organization, phylogenetic comparison, and expression profiles of the SPL family genes and their regulation in soybean. Dev. Genes. Evol. 227, 101 (2017).

Tripathi, R. K., Bregitzer, P. & Singh, J. Genome-wide analysis of the SPL/miR156 module and its interaction with the AP2/miR172 unit in barley. Sci. Rep. 8, 7085 (2018).

Wu, G. et al. The sequential action of miR156 and miR172 regulates developmental timing in Arabidopsis. Cell 138, 750–759 (2009).

He, J. et al. Threshold-dependent repression of SPL gene expression by miR156/miR157 controls vegetative phase change in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Genet. 14, e1007337 (2018).

Wang, L. et al. Coordinated regulation of vegetative and reproductive branching in rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 112, 15504–15509 (2015).

Wei, H., Zhao, Y., Xie, Y. & Wang, H. Exploiting SPL genes to improve maize plant architecture tailored for high-density planting. J. Exp. Bot. 69, 4675–4688 (2018).

Jiao, Y. et al. Regulation of OsSPL14 by OsmiR156 defines ideal plant architecture in rice. Nat. Genet. 42, 541–544 (2010).

Gou, J. et al. The miR156-SPL4 module predominantly regulates aerial axillary bud formation and controls shoot architecture. New Phytol. 216, 829–840 (2017).

Zhang, Y., Schwarz, S., Saedler, H. & Huijser, P. SPL8, a local regulator in a subset of gibberellin-mediated developmental processes in Arabidopsis. Plant Mol. Biol. 63, 429–439 (2007).

Yu, S. et al. Gibberellin regulates the Arabidopsis floral transition through miR156-targeted SQUAMOSA PROMOTER BINDING-LIKE transcription factors. Plant Cell 24, 3320–3332 (2012).

Gou, J.-Y., Felippes, F. F., Liu, C.-J., Weigel, D. & Wang, J.-W. Negative regulation of anthocyanin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis by a miR156-targeted SPL transcription factor. Plant Cell 23, 1512–1522 (2011).

Cui, N. et al. Overexpression of OsmiR156k leads to reduced tolerance to cold stress in rice (Oryza sativa). Mol. Breed. 35, 214 (2015).

Chao, L.-M. et al. Arabidopsis transcription factors SPL1 and SPL12 confer plant thermotolerance at reproductive stage. Mol. Plant 10, 735–748 (2017).

Voinnet, O. Origin, biogenesis, and activity of plant microRNAs. Cell 136, 669–687 (2009).

Chen, X. Small RNAs and their roles in plant development. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. 25, 21–44 (2009).

Gandikota, M. et al. The miRNA156/157 recognition element in the 3’ UTR of the Arabidopsis SBP box gene SPL3 prevents early flowering by translational inhibition in seedlings. Plant J. 49, 683–693 (2007).

Yamaguchi, A. et al. The microRNA-regulated SBP-box transcription factor SPL3 is a direct upstream activator of LEAFY, FRUITFULL, and APETALA1. Dev. Cell 17, 268–278 (2009).

Wang, J.-W., Czech, B. & Weigel, D. miR156-regulated SPL transcription factors define an endogenous flowering pathway in Arabidopsis thaliana. Cell 138, 738–749 (2009).

Xu, M. et al. Developmental functions of miR156-regulated SQUAMOSA PROMOTER BINDING PROTEIN-LIKE (SPL) genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Genet. 12, e1006263 (2017).

Hemming, M. N., Fieg, S., Peacock, W. J., Dennis, E. S. & Trevaskis, B. Regions associated with repression of the barley (Hordeum vulgare) VERNALIZATION1 gene are not required for cold induction. Mol. Genet. Genom. 282, 107–117 (2009).

Li, C. & Dubcovsky, J. Wheat FT protein regulates VRN1 transcription through interactions with FDL2. Plant J. 55, 543–554 (2008).

Shimada, S. et al. A genetic network of flowering-time genes in wheat leaves, in which an APETALA1/FRUITFULL-like gene, VRN1, is upstream of FLOWERING LOCUS T. Plant J. 58, 668–681 (2009).

Wang, H. & Wang, H. The miR156/SPL module, a regulatory hub and versatile toolbox, gears up crops for enhanced agronomic traits. Mol. Plant 8, 677–688 (2015).

Liu, J., Cheng, X., Liu, P. & Sun, J. miR156-targeted SBP-Box transcription factors interact with DWARF53 to regulate TEOSINTE BRANCHED1 and BARREN STALK1 expression in bread wheat. Plant Physiol. 174, 1931–1948 (2017).

Miura, K. et al. OsSPL14 promotes panicle branching and higher grain productivity in rice. Nat. Genet. 42, 545–549 (2010).

Wang, S. et al. Control of grain size, shape and quality by OsSPL16 in rice. Nat. Genet. 44, 950–954 (2012).

Si, L. et al. OsSPL13 controls grain size in cultivated rice. Nat. Genet. 48, 447–456 (2016).

Chuck, G. S., Brown, P. J., Meeley, R. & Hake, S. Maize SBP-box transcription factors unbranched2 and unbranched3 affect yield traits by regulating the rate of lateral primordia initiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 111, 18775–18780 (2014).

Girin, T. et al. Brachypodium: A promising hub between model species and cereals. J. Exp. Bot. 65, 5683–5696 (2014).

Kellogg, E. A. Brachypodium distachyon as a genetic model system. Annu. Rev. Genet. 49, 1–20 (2015).

Woods, D. P. et al. Genetic architecture of flowering-time variation in Brachypodium distachyon. Plant Physiol. 173, 269–279 (2017).

Higgins, J. A., Bailey, P. C. & Laurie, D. A. Comparative genomics of flowering time pathways using Brachypodium distachyon as a model for the temperate grasses. PLoS One 5, e10065 (2010).

Kardailsky, I. et al. Activation tagging of the floral inducer FT. Science 286, 1962–1965 (1999).

Qin, Z. et al. Regulation of FT splicing by an endogenous cue in temperate grasses. Nat Commun. 8, 14320 (2017).

Wu, L. et al. Regulation of FLOWERING LOCUS T by a microRNA in Brachypodium distachyon. Plant Cell 25, 4363–4377 (2013).

Qin, Z. et al. Divergent roles of FT-like 9 in flowering transition under different day lengths in Brachypodium distachyon. Nat. Commun. 10, 812 (2019).

Woods, D. et al. A florigen paralog is required for short-day vernalization in a pooid grass. eLife 8, e42153 (2019).

Takahagi, K. et al. Homoeolog-specific activation of genes for heat acclimation in the allopolyploid grass Brachypodium hybridum. GigaScience 7, giy020 (2018).

van der Schuren, A. et al. Broad spectrum developmental role of Brachypodium AUX 1. New Phytol. 219, 1216–1223 (2018).

Bergonzi, S. et al. Mechanisms of age-dependent response to winter temperature in perennial flowering of Arabis alpina. Science 340, 1094–1097 (2013).

Wu, G. & Poethig, R. S. Temporal regulation of shoot development in Arabidopsis thaliana by miR156 and its target SPL3. Development 133, 3539–3547 (2006).

Cardon, G. H., Hohmann, S., Nettesheim, K., Saedler, H. & Huijser, P. Functional analysis of the Arabidopsis thaliana SBP-box gene SPL3: A novel gene involved in the floral transition. Plant J. 12, 367–377 (1997).

Cai, C., Guo, W. & Zhang, B. Genome-wide identification and characterization of SPL transcription factor family and their evolution and expression profiling analysis in cotton. Sci. Rep. 8, 762 (2018).

Salinas, M., Xing, S., Höhmann, S., Berndtgen, R. & Huijser, P. Genomic organization, phylogenetic comparison and differential expression of the SBP-box family of transcription factors in tomato. Planta 235, 1171–1184 (2012).

Cannon, S. B., Mitra, A., Baumgarten, A., Young, N. D. & May, G. The roles of segmental and tandem gene duplication in the evolution of large gene families in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Plant Biol. 4, 10 (2004).

Bowers, J. E., Chapman, B. A., Rong, J. & Paterson, A. H. Unravelling angiosperm genome evolution by phylogenetic analysis of chromosomal duplication events. Nature 422, 433 (2003).

Cheng, H. et al. Genomic identification, characterization and differential expression analysis of SBP-box gene family in Brassica napus. BMC Plant Biol. 16, 196 (2016).

Lin, E. et al. Molecular characterization of SQUAMOSA PROMOTER BINDING PROTEIN-LIKE (SPL) gene family in Betula luminifera. Front. Plant Sci. 9, 608 (2018).

Wang, S. et al. Non-canonical regulation of SPL transcription factors by a human OTUB1-like deubiquitinase defines a new plant type rice associated with higher grain yield. Cell Res. 27, 1142 (2017).

Rhoades, M. W. et al. Prediction of plant microRNA targets. Cell 110, 513–520 (2002).

Pan, Q., Shai, O., Lee, L. J., Frey, B. J. & Blencowe, B. J. Deep surveying of alternative splicing complexity in the human transcriptome by high-throughput sequencing. Nat. Genet. 40, 1413 (2008).

Lewis, B. P., Green, R. E. & Brenner, S. E. Evidence for the widespread coupling of alternative splicing and nonsense-mediated mRNA decay in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 100, 189–192 (2003).

Silva, E. M. et al. microRNA156-targeted SPL/SBP box transcription factors regulate tomato ovary and fruit development. Plant J. 78, 604–618 (2014).

Wang, Y., Hu, Z., Yang, Y., Chen, X. & Chen, G. Function annotation of an SBP-box gene in Arabidopsis based on analysis of co-expression networks and promoters. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 10, 116–132 (2009).

Nakano, Y., Yamaguchi, M., Endo, H., Rejab, N. A. & Ohtani, M. NAC-MYB-based transcriptional regulation of secondary cell wall biosynthesis in land plants. Front. Plant Sci. 6, 288 (2015).

Yuan, X. et al. Clustered microRNAs’ coordination in regulating protein–protein interaction network. BMC Syst. Biol. 3, 65 (2009).

Ding, X. et al. A rice kinase–protein interaction map. Plant Physiol. 149, 1478–1492 (2009).

Song, X. et al. IPA1 functions as a downstream transcription factor repressed by D53 in strigolactone signaling in rice. Cell Res. 27, 1128–1141 (2017).

Zhou, C. et al. Molecular basis of age-dependent vernalization in Cardamine flexuosa. Science 340, 1097–1100 (2013).

Stief, A. et al. Arabidopsis miR156 regulates tolerance to recurring environmental stress through SPL transcription factors. Plant Cell 26, 1792–1807 (2014)

Guillon, F. et al. A comprehensive overview of grain development in Brachypodium distachyon variety Bd21. J. Exp. Bot. 63, 739–755 (2012).

Kaur, S., Dhugga, K. S., Beech, R. & Singh, J. Genome-wide analysis of the cellulose synthase-like (Csl) gene family in bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). BMC Plant Biol. 17, 193 (2017).

Zhang, B. et al. Molecular characterization and expression analysis of Triticum aestivum squamosal-promoter binding protein-box genes involved in ear development. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 56, 571–581 (2014).

Singh, S., Tripathi, R. K., Lemaux, P. G., Buchanan, B. B. & Singh, J. Redox-dependent interaction between thaumatin-like protein and Î2-glucan influences malting quality of barley. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 20, 201701824 (2017).

Sibout, R. et al. Expression atlas and comparative coexpression network analyses reveal important genes involved in the formation of lignified cell wall in Brachypodium distachyon. New Phytol. 215, 1009–1025 (2017).

Usadel, B. et al. A guide to using MapMan to visualize and compare Omics data in plants: A case study in the crop species, Maize. Plant Cell Environ. 32, 1211–1229 (2009).

Szklarczyk, D. et al. STRING v10: Protein–protein interaction networks, integrated over the tree of life. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, D447–D452 (2014).

Van Bel, M. et al. PLAZA 4.0: An integrative resource for functional, evolutionary and comparative plant genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, 1190–1196 (2017).

Bragg, J. N. et al. Generation and characterization of the Western Regional Research Center Brachypodium T-DNA insertional mutant collection. PLoS One 7, e41916 (2012).

Qin, Z. et al. Regulation of FT splicing by an endogenous cue in temperate grasses. Nat. Commun. 8, 20 (2017).

Singh, M., Singh, S., Randhawa, H. & Singh, J. Polymorphic homoeolog of key gene of RdDM pathway, ARGONAUTE4_9 class is associated with pre-harvest sprouting in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). PloS One 8, e77009 (2013).

Hong, S.-Y., Seo, P. J., Yang, M.-S., Xiang, F. & Park, C.-M. Exploring valid reference genes for gene expression studies in Brachypodium distachyon by real-time PCR. BMC Plant Biol. 8, 112 (2008).

Acknowledgements

The project was supported by a grant to Jaswinder Singh from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada through discovery program (NSERC-Discovery). We thank to Prof. Anja Geitmann lab, McGill University for allowing us to use their SEM facility and Prof. John Vogel, DOE Joint Genome Institute for providing Brachypodium accessions and mutant seeds.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.K.T., J.S.: conceived and designed the experiments. R.K.T.; performed the experiments. W.O.; analysed the T-DNA mutant. R.K.T., J.S.: analysed the data. R.K.T., J.S. wrote the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tripathi, R.K., Overbeek, W. & Singh, J. Global analysis of SBP gene family in Brachypodium distachyon reveals its association with spike development. Sci Rep 10, 15032 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-72005-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-72005-7

This article is cited by

-

Genome-wide identification and analysis of the evolution and expression pattern of the SBP gene family in two Chimonanthus species

Molecular Biology Reports (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.