Abstract

We proposed surface-plasmon-coupled optical force sensors based on metal–insulator–metal (MIM) metamaterials with a movable air gap as an insulator layer. The MIM metamaterial was composed of an air gap sandwiched by a metal nanodot array and a metal diaphragm, the resonant wavelength of which was red-shifted when the air gap was narrowed by applying a normal force. We designed and fabricated a prototype of the proposed sensor and confirmed that the MIM metamaterial could be used as a force sensor with larger sensitivity than a force sensor based on Fabry-Pérot interferometer (FPI).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Optical force sensors offer several advantages such as immunity to electromagnetic interference, no risk of electric shock in biomedical applications, and long-distance measurement using a single optical fiber without complicated wiring compared to electric force sensors1. A typical example of optical force sensors is a force sensor mounted based on Fabry-Pérot interferometer (FPI)2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10, which is utilized for monitoring various biosignals such as blood pressure11, intradiscal pressure12, intracranial pressure13, and intraocular pressure14. The sensitivity of an FPI-based force sensor depends on both the deflection of diaphragm per unit force and the resonant wavelength shift per unit deflection. However, the latter is constant in each resonant mode of FPI; for example, the value becomes 2 in the first resonant mode. Thus, the sensitivity of the sensor depends on only the deflection of diaphragm, which leads to a tradeoff between the high sensitivity and the maximum force capacity.

As with FPI, some photonic metamaterials also show an optical resonant response due to an electromagnetic interaction between an incident light and the subwavelength structure formed in them15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22. One of the photonic metamaterials is a metal–insulator–metal (MIM) metamaterial which shows a dip of the reflectance at a resonant wavelength23,24. This dip is described as the absorption of the light due to localized surface plasmon resonance on two metal layers sandwiching an insulator layer25, which leads to various applications of MIM metamaterials such as refractive index sensors26, color filters27, and absorbers28. According to previous researches, the resonant wavelength depends on the thickness of insulator layer and drastically shifts when the insulator layer becomes narrower29. This shift per unit thickness change can be larger than that of FPI; therefore, there is a possibility to break through the tradeoff of the existing optical force sensors. To our best knowledge, although several force/pressure/strain sensors with nanoplasmonic structure have been proposed so far30,31,32,33,34,35, there is no research on force sensors using the thickness change of the insulator layer in MIM metamaterials.

In this study, we propose a MIM-metamaterial-based force sensor which is composed of an air gap as an insulator layer sandwiched by a metal nanodot array and a metal diaphragm. The insulator layer is the movable air gap that changes with the deflection of diaphragm, which enable MIM metamaterials to be used as a force sensor. Compared to an FPI-based force sensor, the MIM-metamaterial-based force sensor shows larger resonant wavelength shift per unit thickness change of the air gap. Moreover, the resonant wavelength can be designed as the planar size of nanodot pattern in the MIM metamaterial while it can be designed as the thickness of optical cavity in FPI, which means the MIM-metamaterial-based sensor can be thinner when the same resonant wavelength is designed.

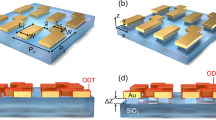

Figure 1 shows a schematic diagram of the MIM-metamaterial-based force sensor, which is composed of an SiO2 diaphragm with an Al film, an air gap, an Al nanodot array, and an SiO2 substrate. The Al nanodot array is capped with SiO2 so as to prevent contact between the Al film and the Al nanodot array when the air gap is narrowed by a normal force applied on the diaphragm. Thus, the MIM metamaterial is composed of the Al film as a top metal layer, the movable air gap and the SiO2 cap as an insulator layer, and the Al nanodot array as a bottom metal layer. With white light incident on the bottom side of the sensor, a strong absorption peak occurs at the resonant wavelength of the MIM metamaterial and is red-shifted as the air gap is narrowed by the force. Therefore, by monitoring the resonant wavelength in the reflectance spectrum, the change of force can be detected. Note that Al is chosen as the material of MIM metamaterials because Al is found better than Au in adhesiveness to SiO2 and better than Ag in oxidative resistance due to the oxide film near the Al surface.

Results

Simulation of optical characteristics

Figure 2a shows a schematic diagram of a unit cell of the nanodot array and a part of the diaphragm opposing the unit cell. The unit cell is square-shaped, 750 nm each side. The Al nanodot and SiO2 cap are also square-shaped at the center of the unit cell, 350 nm each side. The thicknesses of the Al nanodot and SiO2 cap are 30 nm and 25 nm, respectively. The Al film on the diaphragm are positioned above the unit cell with air gap being interposed therebetween, the thickness of which is represented as g. The thickness of the Al film is 100 nm. To investigate optical characteristic changes with respect to g, numerical simulations were carried out by using a commercial software (DiffractMOD, Synopsys, Inc.) based on Rigorous coupled-wave analysis (RCWA) method36. The linearly polarized light was irradiated on the bottom side of the MIM metamaterial vertically, and g was set in the range from 0 to 60 nm.

(a) A schematic diagram of a unit cell of the MIM metamaterial. Simulated results of (b) the reflectance spectra when the thickness of the air gap was 0, 20, 40, or 60 nm and (c) the relationship between the resonant wavelength and the thickness of air gap. (d) The relationships between the change rate of resonant wavelength to thickness of air gap and the thickness of air gap of the MIM metamaterial and FPI. The real parts of (e) the electric field and (f) the magnetic field in the cross section through the center of the unit cell parallel to the x–z plane at g = 40 nm and λ0 = 1,324 nm.

Figure 2b shows the calculated results of the reflectance spectrum. The resonant wavelengths, λ0, at g = 0, 20, 40, and 60 nm were 1,634, 1,370, 1,324, and 1,307 nm, respectively. It can be seen that the resonant wavelength was red-shifted, and the minimum peak value of the reflectance decreased as the air gap became narrower. Figure 2c shows the relationship between the resonant wavelength and the thickness of air gap. This relationship was not linear, and the change rate of resonant wavelength to thickness of air gap became larger as the air gap became narrower. Figure 2d shows the relationships between the change rate of resonant wavelength to thickness of air gap, − Δλ0/Δg (a minus sign is attached because λ0 decreases as g increases), and the thickness of air gap of the MIM metamaterial and FPI. In the case of FPI, the resonant wavelength is equal to 2 times the thickness of air gap in the first resonant mode; therefore, the change rate of resonant wavelength to thickness of air gap is a constant value, 2. In the case of the MIM metamaterial, the change rate of resonant wavelength to thickness of air gap was larger than 2 in the range of the thickness of air gap from 0 to 30 nm.

Since the change of the force on the sensor, ΔF, is detected as the resonant wavelength shift, Δλ0, the sensitivity of the sensor is represented as the change rate of resonant wavelength to force, Δλ0/ΔF. Furthermore, it is also represented as the product of the change rate of resonant wavelength to thickness of air gap, Δλ0/Δg, and the change rate of thickness of air gap to force, Δg/ΔF. Because the latter depends on the mechanical properties of the diaphragm, the difference of the sensitivities between the MIM-metamaterial-based force sensor and FPI-based force sensors is determined by Δλ0/Δg if the same diaphragm is used. From the above results, it can be seen that the sensitivity of the MIM-metamaterial-based sensor is superior to that of an FPI-based force sensor in the range of the thickness of air gap from 0 to 30 nm.

Figures 2e,f show the real parts of the electric field and the magnetic field in the cross section through the center of the unit cell parallel to the x–z plane at g = 40 nm and λ0 = 1,324 nm, which is the resonant wavelength at g = 40 nm, respectively. Enhancements of the electric and magnetic fields were confirmed inside the insulator layer made of the air gap and the SiO2 cap, which indicates that the confinement of electro-magnetic energy in the MIM metamaterial leads to the dissipation of the incident light at the resonant wavelength corresponding to the thickness of air gap as mentioned in the previous research25.

Sensor fabrication

Figure 3a shows schematic diagrams of the fabrication processes. First, an SiO2 substrate with a nanodot array of the sensor was fabricated using a 0.5-mm-thick glass substrate as a starting substrate. Electron-beam (EB) resist was spin-coated on the glass substrate and patterned by EB lithography. Then, Al and SiO2 were deposited with thicknesses of 30 and 25 nm by EB vapor deposition, respectively. The nanodot array was fabricated by removing the EB resist and Al/SiO2 layer on it by lift-off process. Next, an SiO2 diaphragm with an Al film was fabricated using a 1-mm-thick glass substrate as a starting substrate. The diameter of the diaphragm was 6 mm. Patterning photo resist as a mask, the glass substrate was etched by a 200-nm-depth by ion-beam milling. Then, the Al film was fabricated by depositing Al by a 100-nm-thickness by EB vapor deposition and removing unnecessary photoresist and Al layers. Finally, the SiO2 substrate with the nanodot array and the SiO2 diaphragm with the Al film were bonded by curing UV curable resin around the contact region between them. With the above fabrication processes, the initial thickness of air gap g0 should be 45 nm. However, we observed interference fringes on the contact region between the SiO2 substrate and the SiO2 diaphragm, which indicated some gap existed in the contact region and the initial thickness of air gap was larger than 45 nm. One of the possible causes of the gap is the presence of particles left on the contact region.

Figure 3b shows a photograph of the SiO2 substrate with the nanodot array. The nanodot array was fabricated in a 1 mm square near the center of the SiO2 substrate. Figure 3c shows a photograph of the fabricated sensor after bonding the SiO2 substrate and the SiO2 diaphragm. Figure 3d,e shows scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of an overview and a unit cell of the nanodot array. From the SEM observation, it was confirmed that the nanodot array was fabricated with sufficient accuracy to match the design value.

Evaluation of sensitivity

Change of the optical characteristics of the fabricated sensor was measured by applying a normal force on the top side of the sensor. Figure 4a shows the experimental setup, which was composed of a z-axis automatic stage, a force gauge, the fabricated sensor, a halogen lamp, a half mirror, lenses, a spectrometer and PC for data acquisition. A normal force was applied by pushing the sensor with the tip of the force gauge which was moved vertically by the z-axis automatic stage as shown in Fig. 4b. White light emitted by the halogen lamp was incident on the bottom side of the sensor through the half mirror and lenses, was reflected on the MIM metamaterial, and entered in the spectrometer. Figure 4c shows the measured reflectance spectra when the force, F, was 8.5, 9.0, 9.5, and 10.0 N. As the force increased, the resonant wavelength was red-shifted and the reflectance at the resonant wavelength decreased, which corresponded to the simulated results shown in Fig. 2b. The resonant wavelengths at F = 8.5, 9.0, 9.5, and 10.0 N were 1,425, 1,446, 1,521, and 1,621 nm, respectively. Note that the force unit N is used instead of the pressure unit Pa because it is difficult to apply uniform pressure to the diaphragm with the experimental setup.

(a) Experimental setup for measurement of optical characteristic change of the fabricated MIM metamaterial while a normal force is applied. (b) A photograph of the tip of the force gauge pushing the diaphragm of the fabricated sensor. (c) Measurement results of the reflectance spectra. The relationships (d) between the resonant wavelength shift and the change of air gap and (e) between the change rate of resonant wavelength to thickness of air gap and the change of air gap.

To evaluate the change rate of resonant wavelength to thickness of air gap of fabricated sensor, we estimated the change of air gap, Δg, corresponding to the applied force. We used the relationship between the deflection change of diaphragm, Δw = − Δg, and the force change, ΔF, which depends on the mechanical properties of the diaphragm. According to the theory of plates and shells37, the deflection change at the center of the diaphragm where point load is applied is represented as Δw = 3a2(1 − ν2)ΔF/(4πEh3); here, a is the radius, ν is the Poisson’s ratio, E is the Young’s modulus, and h is the thickness of the diaphragm. By substituting the design values (a = 3 mm, h = 1 mm) and the material properties of glass (E = 71.6 GPa, ν = 0.23) to the above equation and considering F = 10.0 N as a reference point, the changes of air gap, Δg, at F = 8.5, 9.0, 9.5, and 10.0 N were estimated as 42.6, 28.4, 14.2, and 0 nm, respectively. Also, the resonant wavelength shifts, Δλ0, at F = 8.5, 9.0, 9.5, and 10.0 N were − 196, − 175, − 100, and 0 nm, respectively. Figure 4d shows the relationship between the resonant wavelength shift and the estimated change of air gap of fabricated sensor, where the quadratic regression curve is plotted together. This relationship was not linear as predicted in the simulation result shown in Fig. 2c. Figure 4e shows the change rate of resonant wavelength to thickness of air gap of fabricated sensor, which was calculated by differentiating the regression curve shown in Fig. 4d. The change rate of fabricated sensor was larger than that of FPI in the range of the applied force from 8.8 to 10.0 N. This result shows the MIM-metamaterial-based force sensor has larger sensitivity than an FPI-based force sensor in this range if the same diaphragm is used. Because the range where the sensitivity is higher can be controlled by changing the stiffness of the diaphragm and the initial thickness of air gap, the conventional tradeoff between the sensitivity and the maximum force capacity of FPI-based force sensors can be broken through in the desired range of use.

Discussion

We proposed the MIM-metamaterial-based force sensor with a movable insulator layer made of an air gap. The MIM metamaterial is composed of the Al film on the SiO2 diaphragm as a top metal layer, the Al nanodot array on the SiO2 substrate as a bottom metal layer, and the air gap and the SiO2 cap on the nanodot as an insulator layer. Enhancements of the electric and magnetic fields inside the MIM metamaterial were confirmed by RCWA simulation. A prototype of the MIM-metamaterial-based force sensor was designed and fabricated. The fabricated sensor shows the resonant wavelength shift along with the change of the force applied on the diaphragm. By estimating the change of air gap corresponding to the force, the relationship between the change rate of resonant wavelength to thickness of air gap and the change of air gap were evaluated. The result shows the MIM-metamaterial-based force sensor has larger sensitivity than an FPI-based force sensor in the range of the force from 8.8 to 10 N if the same diaphragm is used, which is promising because the tradeoff between the sensitivity and the maximum force capacity inherent in FPI-based force sensors can be break thorough.

While the sensitivity is remarkable, one of the limitations of the proposed sensor is the difficulty in fabricating a nanoscale air gap with the same thickness as the design value, which leads to a variation of the sensitivity. In order to improve the fabrication accuracy, it is necessary to optimize the fabrication processes and conditions. Especially, the bonding process of the SiO2 diaphragm and the SiO2 substrate may affect the sensitivity heavily. The presence of substances that remain on the bonded surface will increase the initial thickness of air gap. Also, because of the stiffness of the substances themselves, the deflection of the diaphragm does not match the change of air gap, that is, Δw ≠ − Δg. Thus, the estimated change of air gap shown in Fig. 4d,e includes an error, which is the reason why the characteristic of the fabricated sensor shown in Fig. 4e seems to be linear unlike the simulation result shown in Fig. 2d.

Another limitation is the sensitivity change due to the position of the point load applied on the diaphragm. If the position of point load deviates from the center of the diaphragm, the relationship between the force and the change in air gap varies. The same can be said when a distributed pressure is applied. In practical use, the position of the point load must be fixed not to change the sensitivity. As a future work, sensor housings that transfers a point load to the center of the diaphragm need to be designed and combined with the proposed MIM-metamaterial-based sensor as a force-sensing element.

Methods

Simulation conditions

The simulations were conducted with a commercial software (DiffractMOD, Synopsys, Inc.) as follows. Both width and height of a unit cell were 750 nm. Both width and height of Al nanodot and SiO2 cap were 350 nm. The thickness of Al nanodot and SiO2 cap were 30 nm and 25 nm, respectively. Al film was placed away from the top of the SiO2 cap by the thickness of air gap, g. The calculation area was set from 50 nm below the Al nanodot to 30 nm above the air gap. The thickness of air gap, g, was set in the range from 0 to 30 nm with 1 nm step while in the range from 30 to 60 nm with 5 nm step. The materials of components were chosen from Rsoft library built in by default. In the calculation of reflective spectra, harmonics and wavelength step parameters were set to 6 and 2 nm, respectively. In the calculation of electric and magnetic fields, harmonics was set to 13.

References

Roriz, P., Frazão, O., Lobo-Ribeiro, A. B., Santos, J. L. & Simões, J. A. Review of fiber-optic pressure sensors for biomedical and biomechanical applications. J. Biomed. Opt. 18, 050903 (2013).

Tohyama, O., Kohashi, M., Yamamoto, K. & Itoh, H. A fiber-optic silicon pressure sensor for ultra-thin catheters. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 54, 622–625 (1996).

Totsu, K., Haga, Y. & Esashi, M. Ultra-miniature fiber-optic pressure sensor using white light interferometry. J. Micromech. Microeng. 15, 71–75 (2005).

Hill, G. C. et al. SU-8 MEMS Fabry-Perot pressure sensor. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 138, 52–62 (2007).

Bae, H. & Yu, M. Miniature Fabry-Perot pressure sensor created by using UV-molding process with an optical fiber based mold. Opt. Express 20, 14573–14583 (2012).

Eom, J. et al. Fiber optic Fabry-Perot pressure sensor based on lensed fiber and polymeric diaphragm. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 225, 25–32 (2015).

Li, C., Xiao, J., Guo, T., Fan, S. & Jin, W. Interference characteristics in a Fabry-Perot cavity with graphene membrane for optical fiber pressure sensors. Microsyst. Technol. 21, 2297–2306 (2015).

Guermat, A., Guessoum, A., Demagh, N.-E., Zaboub, M. & Bouhafs, Z. Fibre-optic temperature and pressure sensor based on a deformable concave micro-mirror. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 270, 205–213 (2018).

Wu, J. et al. Optical fiber-tip Fabry-Pérot interferometric pressure sensor based on an in situ μ-printed air cavity. J. Lightw. Technol. 36, 3618–3623 (2018).

Ma, W. et al. Microelectromechanical system-based, high-finesse, optical fiber Fabry-Perot interferometric pressure sensors. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 302, 111795 (2020).

Wu, N. et al. A miniature fiber optic blood pressure sensor and its application in in vivo blood pressure measurements of a swine model. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 181, 172–178 (2013).

Nesson, S., Yu, M., Zhang, X. & Hsieh, A. H. Miniature fiber optic pressure sensor with composite polymer-metal diaphragm for intradiscal pressure measurements. J. Biomed. Opt. 13, 044040 (2008).

Shin, J. et al. Bioresorbable optical sensor systems for monitoring of intracranial pressure and temperature. Sci. Adv. 5, 1899 (2019).

Lee, J. O. et al. Fabry-Pérot optical sensor and portable detector for monitoring high-resolution ocular hemodynamics. IEEE Photon. Technol. Lett. 31, 423–426 (2018).

Pendry, J. B., Holden, A. J., Robbins, D. J. & Stewart, W. J. Magnetism from conductors and enhanced nonlinear phenomena. IEEE Trans. Microw. Theory Techn. 47, 2075–2084 (1999).

Ishikawa, A., Tanaka, T. & Kawata, S. Negative magnetic permeability in the visible light region. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 237401 (2005).

Hokari, R., Kanamori, Y. & Hane, K. Comparison of electromagnetically induced transparency between silver, gold, and aluminum metamaterials at visible wavelengths. Opt. Express 22, 3526–3537 (2014).

Hokari, R., Kanamori, Y. & Hane, K. Fabrication of planar metamaterials with sharp and strong electromagnetically induced transparency like characteristics at wavelengths around 820 nm. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 31, 1000–1005 (2014).

Kanamori, Y., Hokari, R. & Hane, K. MEMS for plasmon control of optical metamaterials. IEEE J. Sel. Topics Quant. Electron. 21, 2701410 (2015).

Moritake, Y., Kanamori, Y. & Hane, K. Enhanced quality factor of Fano resonance in optical metamaterials by manipulating configuration of unit cells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 107, 211108 (2015).

Moritake, Y., Kanamori, Y. & Hane, K. Demonstration of sharp multiple Fano resonances in optical metamaterials. Opt. Express 24, 9332–9339 (2016).

Moritake, Y., Kanamori, Y. & Hane, K. Emission wavelength tuning of fluorescence by fine structural control of optical metamaterials with Fano resonance. Sci. Rep. 6, 33208 (2016).

Atre, A. C., García-Etxarri, A., Alaeian, H. & Dionne, J. A. A broadband negative index metamaterial at optical frequencies. Adv. Opt. Mater. 1, 327–333 (2013).

Hu, C., Zhao, Z., Chen, X. & Luo, X. Realizing near-perfect absorption at visible frequencies. Opt. Express 17, 11039–11044 (2009).

Sakurai, A., Zhao, B. & Zhang, Z. M. Resonant frequency and bandwidth of metamaterial emitters and absorbers predicted by an RLC circuit model. J. Quant. Spectrosc. Radiat. Transf. 149, 33–40 (2014).

Liu, N., Mesch, M., Weiss, T., Hentschel, M. & Giessen, H. Infrared perfect absorber and its application as plasmonic sensor. Nano Lett. 10, 2342–2348 (2010).

Mudachathi, R. & Tanaka, T. Up scalable full colour plasmonic pixels with controllable hue, brightness and saturation. Sci. Rep. 7, 1199 (2017).

Ogawa, S. & Kimata, M. Metal-insulator-metal-based plasmonic metamaterial absorbers at visible and infrared wavelengths: A review. Materials 11, 458 (2018).

Hao, J. et al. High performance optical absorber based on a plasmonic metamaterial. Appl. Phys. Lett. 96, 251104 (2010).

Pryce, I. M., Aydin, K., Kelaita, Y. A., Briggs, R. M. & Atwater, H. A. Highly strained compliant optical metamaterials with frequency tunability. Nano Lett. 10, 4222–4227 (2010).

Cui, Y., Zhou, J., Tamma, V. A. & Park, W. Dynamic tuning and symmetry lowering of fano resonance in plasmonic nanostructure. ACS Nano 6, 2385–2393 (2012).

Han, X., Liu, Y. & Yin, Y. Colorimetric stress memory sensor based on disassembly of gold nanoparticle chains. Nano Lett. 14, 2466–2470 (2014).

Rankin, A. & McGarry, S. A flexible pressure sensitive colour changing device using plasmonic nanoparticles. Nanotechnology 26, 075502 (2015).

Minati, L. et al. Gold nanoparticles 1D array as mechanochromic strain sensor. Mater. Chem. Phys. 192, 94–99 (2017).

Topcu, G., Guner, T., Inci, E. & Demir, M. M. Colorimetric and plasmonic pressure sensors based on polyacrylamide/Au nanoparticles. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 295, 503–511 (2019).

Moharam, M. G. & Gaylord, T. K. Rigorous coupled-wave analysis of planar-grating diffraction. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 71, 811–818 (1981).

Timoshenko, S. & Woinowsky-Krieger, S. Theory of Plates and Shells 2nd edn. (McGraw-Hill Book Co., Boca Raton, 1959).

Acknowledgements

A part of this research was funded by the MEXT JSPS KAKENHI 19K22097 and performed in Micro/Nano-Machining Research and Education Center, Tohoku University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.S. K.H. and Y.K. conceived the fabrication processes and designed the experiments. S.S. conducted the simulations, fabrications and experiments. T.O. and S.S. analyzed the results and wrote the main manuscript text. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Okatani, T., Sekiguchi, S., Hane, K. et al. Surface-plasmon-coupled optical force sensors based on metal–insulator–metal metamaterials with movable air gap. Sci Rep 10, 14807 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-71825-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-71825-x

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.