Abstract

We show an annual overview of the sea-air CO2 exchanges and primary drivers in the Gerlache Strait, a hotspot for climate change that is ecologically important in the northern Antarctic Peninsula. In autumn and winter, episodic upwelling events increase the remineralized carbon in the sea surface, leading the region to act as a moderate or strong CO2 source to the atmosphere of up to 40 mmol m–2 day–1. During summer and late spring, photosynthesis decreases the CO2 partial pressure in the surface seawater, enhancing ocean CO2 uptake, which reaches values higher than − 40 mmol m–2 day–1. Thus, autumn/winter CO2 outgassing is nearly balanced by an only 4-month period of intense ocean CO2 ingassing during summer/spring. Hence, the estimated annual net sea-air CO2 flux from 2002 to 2017 was 1.24 ± 4.33 mmol m–2 day–1, opposing the common CO2 sink behaviour observed in other coastal regions around Antarctica. The main drivers of changes in the surface CO2 system in this region were total dissolved inorganic carbon and total alkalinity, revealing dominant influences of both physical and biological processes. These findings demonstrate the importance of Antarctica coastal zones as summer carbon sinks and emphasize the need to better understand local/regional seasonal sensitivity to the net CO2 flux effect on the Southern Ocean carbon cycle, especially considering the impacts caused by climate change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The investigation of Antarctic coastal regions has long been neglected because they are difficult to access1,2,3,4, especially during periods other than the austral summer5,6,7,8. This occurs because of most of the year, i.e., from April to November, these regions are almost completely or completely covered by sea ice9,10. Such conditions lead to a biased representation of sampling in autumn and winter, which are likely critical periods for changes in seawater carbonate chemistry and net sea-air CO2 flux (FCO2). In fact, several studies have been conducted during the austral summer to better understand the FCO211,12,13,14,15,16 and carbonate system parameter variability17,18,19,20,21,22 in the remote Southern Ocean. It is widely known that the Antarctic coasts behave as a strong CO2 sink during the summer15,23, which has intensified during recent years14,15. Actually, the intensity of this behaviour is marked by high interannual variability, since the summer CO2 fluxes in the Gerlache Strait, for example, oscillate between periods of strong CO2 sink (i.e., < − 12 mmol m–2 day–1) and sea-air near-equilibrium conditions at inter-annual scales15. However, even when Antarctic coastal regions do not behave as a strong CO2 sink, they take up CO2 in the summer15, although eventual episodes of CO2 outgassing can occur20.

Although some studies have provided important information on the seasonality of the FCO27,8,19, they are restricted to a few specific years or localized regions, which may bias the modelled long-term trends of these regions. Hence, understanding the annual budget of sea-air CO2 exchanges remains a challenge4,24. This is particularly true for the Gerlache Strait and likely other major embayments around the Antarctic coasts, since it remains unclear whether this CO2 sink behaviour persists throughout the year or is balanced in other seasons. Moreover, little is known about the main drivers of FCO2 seasonality and their consequences for the sea surface carbonate system. Therefore, here, we present an annual overview of the FCO2 and the carbonate system properties in the Gerlache Strait, an ecologically and climatically important area of the northern Antarctic Peninsula (NAP). Furthermore, we demonstrate that this region acted as an annual net CO2 source to the atmosphere from 2002 to 2017, contrasting with previous findings for the western Antarctic Peninsula environments7,8,19 and other regions around Antarctica25,26,27.

Oceanographic features of the Gerlache Strait

The Gerlache Strait is a coastal region along the NAP that is being impacted by climate change24,28 and is essential for the health of the Antarctic food web29,30,31. The strait is a shallow basin that lies between the NAP and the Palmer Archipelago and is connected to the Bellingshausen Sea (to the west) and the Bransfield Strait (to the north) (Fig. 1a,b). Although it covers a smaller area (~ 8000 km2) than other coastal regions around the NAP, the Gerlache Strait is a highly productive coastal zone. In the Gerlache Strait, records of chlorophyll a (used as an indicator of primary producer biomass) range from ~ 2.0 mg m–331 to ~ 23 mg m–332 under distinct austral summer conditions. These concentrations have the same or a greater magnitude than those observed in more extensive regions, such as the Bransfield Strait (4.4 ± 3.84 mg m–3)32 and the northwestern Weddell Sea (1.38 ± 2.01 mg m–3)33. In addition, the Gerlache Strait has experienced intense diatom blooms reaching > 45 mg m–3 of chlorophyll a32. Although higher, this value is consistent with that recorded in the vicinity of Palmer Station, in the southernmost part of the Gerlache Strait, where the maximum chlorophyll a recorded was ~ 30 mg m–334.

Location of the (a) western and northern Antarctic Peninsula and the (b) Gerlache Strait, with a simplified surface circulation pattern (red arrows) that is strongly influenced by the Bellingshausen Sea. The surface circulation in (b) was based on Savidge and Amft98. The dashed red arrows represent the modified Circumpolar Deep Water intrusions into the strait, which were identified by Smith et al.42, Prézelin et al.36 and García et al.43. The green square depicts the U.S. Palmer Station location (64.8°S, 64.1°W), from which we extracted atmospheric data. The colour shading represents the bottom bathymetry. These maps were generated by using the software Ocean Data View (v. 5.3.0, https://odv.awi.de)100.

The high biological productivity in this region, reflected at different trophic levels35, is mainly due to the complex interplay of its distinct water mass sources, sea ice dynamics, ocean circulation, nutrient-rich meltwater input and protection from severe weather conditions36,37. Additionally, the rapid effects of climate change24,28,38, a recent increase in glacial meltwater discharge39, and likely the advection of both organic and anthropogenic carbon around the NAP21,40,41 have influenced the coupled physical-biological processes changing the carbon biogeochemistry across the entire western Antarctic Peninsula shelf region28,39.

Moreover, the Gerlache Strait is affected by irregular intrusions of Circumpolar Deep Water (CDW; e.g., Refs.36,42,43,44) (Fig. 1b). CDW is a warm, salty, poorly oxygenated and carbon- and nutrient-rich water mass flowing eastward with the Antarctic Circumpolar Current at intermediate and deep levels around the continent43,45,46. CDW intrusions along the western shelf of the Antarctic Peninsula are often associated with upwelling, mainly caused by shallow bathymetry47 and predominant wind systems36. These intrusions are also affected by modes of climate variability that regulate the intensity of winds in the Southern Ocean, such as the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and Southern Annular Mode (SAM)45,48,49. During the positive phases of the SAM, the westerly winds are intensified, and the frequency and intensity of episodic CDW intrusions increase45. Conversely, under extreme ENSO, winds are weakened and cooled48, probably reducing CDW intrusions on the western shelf of the Antarctic Peninsula. Under any of these conditions, the physical properties of CDW change when it is mixed with cooler and less saline surface waters, originating the modified CDW (mCDW) in the shelf and coastal domain.

At depths greater than 100 m, the Gerlache Strait is influenced by the mixing of water masses sourced from the Bellingshausen and Weddell seas. In addition to mCDW, the north of the strait is influenced by a modified variety of High Salinity Shelf Water (HSSW), which is cooler and more oxygenated than CDW45,50. HSSW is formed on the northwestern Weddell Sea continental shelf and is advected towards and along the Bransfield Strait by the Antarctic Coastal Current50,51. Signs of its presence at deep levels of the Gerlache Strait are an important aspect of the NAP because HSSW is younger than CDW, and the biogeochemical impact of mixing between the modified varieties of these waters is not yet completely understood21,22,40. However, a consequence of HSSW is the intrusion of anthropogenic carbon in deep levels of the strait25,26, which can intensify the ocean acidification process in the region.

Results

Hydrographic properties and the carbonate system

Negative sea surface temperatures were recorded from April to November (Fig. 2a), and the lowest values in summer were observed in the northernmost part of the strait, where the highest salinities were recorded (Figure S4). The opposite temperature distribution pattern occurred during spring, when the lowest temperatures were recorded at the southern end of the strait. At the connection between the central basin of the Gerlache Strait and the Bellingshausen Sea (i.e., Schollaert Channel), higher temperatures were associated with lower salinity (Figure S4). On the other hand, the spatial distributions of temperature and salinity in autumn and winter were more homogeneous than those in summer and spring. The carbonate system properties also demonstrated distinct spatial distribution patterns among seasons (Figures S5–S8). The seasonal variabilities of total alkalinity (AT) and total dissolved inorganic carbon (CT) followed that of seawater CO2 partial pressure (pCO2sw) and were inverse to those of pH and the calcite and aragonite saturation states (ΩCa and ΩAr, respectively) throughout the year. AT was higher than CT from December to March and was lower than CT during the rest of the year (Fig. 2d). This seasonal pattern was also observed for CO2 saturation relative to the atmosphere; i.e., the difference (∆pCO2) between pCO2sw and the CO2 partial pressure in the atmosphere (pCO2atm) was positive from April to November and negative from December to March (Fig. 2b). Minimum pH values (total scale) of 7.99 ± 0.02 were observed in winter, while in the other seasons, they were equal to or greater than 8.00 (Fig. 2c). Undersaturated carbonate calcium conditions (i.e., Ω less than 1) were not observed for either species during the seasonal cycle (Fig. 2c), although the lowest surface values of ΩCa and ΩAr were recorded in winter, on average.

Detrended annual cycle of hydrographic and carbonate system properties on the surface of the Gerlache Strait. (a) Temperature and salinity, (b) CO2 partial pressure in the sea surface (pCO2sw) and the difference between pCO2sw and atmospheric pCO2 (∆pCO2), (c) pH (total scale) and saturation states of calcite (ΩCa) and aragonite (ΩAr), and (d) total alkalinity (AT) and total dissolved inorganic carbon (CT). The blue bars are the standard deviations oriented up or down for visual clarity. The horizontal lines are the boundaries of 0 °C (a) and a ∆pCO2 equal to 0 (b).

In summer, virtually all processes exerted some influence on the surface CO2 system, as shown by the wide dispersion of the salinity-normalized AT and CT (nAT and nCT, respectively; Fig. 3a). In general, carbonate dissolution seems to exert a greater influence in autumn and winter than in spring and summer, although sea ice growth also acts to control AT and CT in winter. Carbonate dissolution/calcification processes were observed to play a role in changing the AT and CT surface distributions in spring, although sea ice growth and melting processes are also expected to exert an influence, mainly during October and November, in association with low temperatures (Fig. 3d) and high pCO2sw. On the other hand, high temperatures (> 0 °C) in spring were associated with an increased influence of photosynthesis on the AT and CT (Fig. 3d).

Salinity-normalized (average salinity for each season as in Figure S4) total alkalinity and total dissolved inorganic carbon (nAT and nCT, respectively) dispersal diagram for the (a) summer, (b) autumn, (c) winter, and (d) spring. nAT and nCT were calculated for non-zero salinities following Friis et al.99. Arrows represent the nAT:nCT ratio that characterizes the physical-biogeochemical processes that affect nAT and nCT (adapted from Zeebe56). The theoretical arrow representing the sea ice growth and melt processes was based on the threshold values for AT and CT described in Rysgaard et al.64. More details about the normalization of AT and CT as well as sea ice growth and melt processes are provided in the Supplementary Material. Note that the magnitudes of the axes are different among subplots.

Drivers of pCO2 sw seasonal changes

CT had the dominant effect on changes in pCO2sw throughout the year. AT and temperature were secondary drivers of these changes, while salinity had a minor influence on surface pCO2sw (Fig. 4). In summer and spring, there was a considerable decrease in pCO2sw, mainly due to the CT drawdown. This decrease was compensated by the increasing effect on pCO2sw of the reduction in AT and the increase in temperature. In winter and autumn, the considerable increase in pCO2sw was driven by the increase in CT and partially compensated for by the increase in AT and decrease in temperature.

Effects of total alkalinity (AT), total dissolved inorganic carbon (CT), sea surface temperature (SST) and sea surface salinity (SSS) on seawater pCO2 (pCO2sw) for each season in the Gerlache Strait. The variation in each parameter is calculated as the difference between the values of each parameter and their respective averages in previous seasons. The unit of all drivers is the same as that for pCO2sw (µatm), and their magnitudes represent their influence on pCO2sw changes. Positive values indicate that an increase in the parameter led to an increase in pCO2sw; negative values indicate that a decrease in the parameter led to a decrease in pCO2sw. The only exception to this is AT because an increase in AT leads to a decrease in pCO2sw and vice versa. The error bars (purple) show the difference between the sum of all drivers and the actual variation in pCO2sw (∆pCO2drv), indicating the extent to which the decomposition of pCO2sw into its drivers differs from ΔpCO2drv. More details are given in the methods section.

Net sea-air CO2 fluxes (FCO2)

FCO2 exhibited distinct seasonality throughout the year, with the region swinging from a strong CO2 sink (FCO2 < − 12 mmol m–2 day–1) in summer to a strong CO2 source (FCO2 > 12 mmol m–2 day–1) in winter (Fig. 5). During autumn and spring, the behaviour of the region oscillated between the major situations normally observed during winter and summer, resulting in a moderate FCO2. Despite this well-marked seasonality, the region was an annual weak CO2 source from 2002 to 2017, with an average estimated FCO2 of 1.24 ± 4.33 mmol m–2 day–1. Notably, with high spatial and temporal variability, this net near-equilibrium condition was achieved because the region switched from a moderate to strong CO2 ocean sink from December to March to a moderate to strong CO2 source to the atmosphere throughout the rest of the year (Fig. 5). Months with the most intense CO2 uptake levels (< − 12 mmol m–2 day–1) have occurred more frequently since 2011, with the peak in January and February of 2016. On the other hand, months with the maximum CO2 outgassing (> 12 mmol m–2 day–1) seem to have become less frequent since 2009 (Fig. 5).

Monthly averages of net sea-air CO2 fluxes (FCO2) in the Gerlache Strait from January 2002 to December 2017 with an inset showing the variability throughout the year to characterize the seasonal cycle of FCO2 and the percentage of sea ice cover (filled blue bars). The gaps are from years when there was no winter sampling in the region. The blue bars oriented upwards are the standard deviations from the respective monthly averages, as are the black bars in the inset. Positive FCO2 values represent the outgassing of CO2 to the atmosphere, whereas negative FCO2 values represent CO2 uptake by the ocean.

Considering all seasons between 2002 and 2017, high seasonal variability in FCO2 magnitude was identified (Fig. 6). However, the behaviour of the Gerlache Strait as a CO2 sink or source remained almost consistent within each season, as observed in summer (Fig. 6b) and winter (Fig. 6d). Only two particular exceptions occurred in the autumns of 2011 and 2014, when the region was a weak CO2 sink (Fig. 6c). Exceptions were also identified in spring, when the region behaved as a strong CO2 source in 2008 and a particularly strong CO2 sink in 2010 (Fig. 6e). Although the specific episodes in autumn did not appear to influence the average annual FCO2, the unusual spring FCO2 magnitudes coincided with increases in the average annual FCO2 in the respective years (Fig. 6a). The Gerlache Strait acted as an absolute annual CO2 source of 4.4 ± 2.8 mmol m–2 day–1 from 2002 to 2009 and has become predominantly a net annual CO2 sink of − 2.0 ± 3.0 mmol m–2 day–1 since 2010 (Fig. 6a).

Time series of average (a) annual net sea-air CO2 flux (FCO2) during (b) summer, (c) autumn, (d) winter and (e) spring in the Gerlache Strait from 2002 to 2017. The gaps are from years when there was no winter sampling in the region. The blue bars oriented upwards are the standard deviations from the respective annual averages. Positive FCO2 values represent the outgassing of CO2 to the atmosphere, whereas negative values represent CO2 uptake by the ocean.

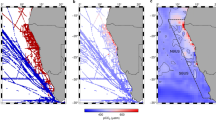

A seasonal pattern in the spatial distribution of FCO2 along the Gerlache Strait was also identified. This pattern was characterized by a more homogeneous spatial distribution in autumn and winter (Fig. 7b,c) than in summer and spring (Fig. 7a,d). Moreover, the northernmost part of the strait, north of 64°S, had a higher annual FCO2 (3 ± 8 mmol m–2 day–1) than the southernmost part of the strait, south of 65°S. In the southernmost part, there was an annual CO2 uptake of − 7 ± 16 mmol m–2 day–1.

Surface distribution of the net sea-air CO2 flux (FCO2) in the Gerlache Strait from 2002 to 2017 in (a) summer, (b) autumn, (c) winter and (d) spring. Positive FCO2 values represent the outgassing of CO2 to the atmosphere, whereas negative FCO2 values represent CO2 uptake by the ocean. The numbers indicate the averages and standard deviations of FCO2 in each season. The black continuous and dashed isolines depict the FCO2 values of –12 and + 12 mmol m–2 d–1, respectively, for the strong CO2 sink and outgassing situations. These maps were generated by using the software Ocean Data View (v. 5.3.0, https://odv.awi.de)100.

Discussion

Seasonal changes in sea-air CO2 fluxes

In late spring and summer, the Gerlache Strait is a CO2 sink, with rates ranging from − 13 ± 12 mmol m–2 day–1 in January to − 5 ± 9 mmol m–2 day–1 in March (Fig. 5). This strong CO2 uptake is driven by an increase in biological activity coupled with meltwater input (Fig. 8a)14,15,20,52,53,54 from December until late summer (Fig. 5), when sea ice formation becomes gradually more intense9,10. This is revealed by the substantial CT drawdown (Fig. 4), which characterizes the influence of photosynthesis on the surface water3,55,56, associated with a slight decrease in AT as a result of further respiration (Fig. 3b). Phytoplankton growth is favoured by the increased stability of the nutrient-rich shallower mixed layer in summer and late spring (Fig. 8a), mainly due to meltwater input14, 46,53,54,57. This is more evident in the southernmost part of the strait, where intrusions of warmer mCDW would likely lead to sea ice melting36 and the higher percentage of meteoric water (Figure S9) than in the northernmost region, which is comparatively ice-free (Figure S9). Hence, this could potentially account for the greater CO2 uptake in the southern region than in the northern region (Fig. 7). Nevertheless, the spatial variability of the carbonate system parameters is clearly greater in spring and summer than in autumn and winter. Therefore, it is likely that other oceanographic processes simultaneously have roles in changing the surface nAT and nCT.

Distinct processes driving surface CO2 partial pressure (pCO2) and seasonal sea-air CO2 fluxes in a coastal region of the northern Antarctic Peninsula (NAP). From (a) December to March, sea ice melting provides a shallow mixed layer that leads to phytoplankton growth. This spring–summer scenario coupled with less intense modified Circumpolar Deep Water (mCDW) intrusions into the NAP and a decrease in total dissolved inorganic carbon (CT) from meltwater causes pCO2 drawdown. Therefore, in these months, the region behaves as a strong sink of atmospheric CO2. Conversely, from (b) April to November, under sea ice cover conditions, more intense mCDW intrusions coupled with a deeper mixed layer lead to intensified vertical mixing, resulting in the upwelling of CO2-rich waters. Such processes, in association with the rejection of CT through brine release during sea ice growth, lead to a significant increase in surface pCO2. Then, the region becomes a moderate to strong CO2 source to the atmosphere during the autumn–winter. The theoretical depth of the shallowest spring–summer mixed layer is approximately 50 m, reaching approximately 150 m in the autumn–winter61. Drawn by Thiago Monteiro. Symbols courtesy of the Integration and Application Network, University of Maryland Center for Envrionmental Science (ian.umces.edu/symbols/).

In fact, during early spring, the carbonate dissolution/precipitation and sea ice growth/melt associated with low temperatures (Fig. 3d) seem to influence the carbonate system due to the increase in CT that is rejected through the sea ice brine. However, the impact of each of these processes, and even the presence of other involved processes, is not yet well understood. The dominant processes in spring (i.e., carbonate dissolution/precipitation or photosynthesis/respiration), as well as during other seasons, can also exhibit interannual variability. For example, during summer, there is variability in CO2 uptake oscillating between 2 and 4 years, by which FCO2 in the region alternates between strong CO2 sink and near-equilibrium conditions15. This variability is associated with both intense biological activity and the intrusion of local upwelled CO2-rich waters (e.g., mCDW). In addition, it is linked to the influence of modes of climate variability, such as ENSO, which decreases the wind intensity, leading to favourable conditions for phytoplankton blooms14. This explains why the most intense CO2 uptake was recorded in 2016 (Fig. 5), as this was the year with the most extreme ENSO since 199858, which was associated with biogeochemical changes along the water column41. Therefore, the same mechanism underlying the shift in the dominant physical processes may occur in other seasons of the year. This would likely explain why the region was an exceptionally strong CO2 source in spring 2008 but a strong CO2 sink in spring 2010 (Fig. 6e).

In autumn, the region becomes a moderate CO2 source to the atmosphere, with the maximum magnitude in August (14 ± 7 mmol m–2 day–1). Such behaviour is due to a significant increase in CT, which leads to an increase in pCO2sw. This is further partially offset by the effect that the increase in AT has on pCO2sw (Fig. 4), implicating the upwelling process as a likely cause. In fact, more intense short-term irregular intrusions of mCDW44,59,60 coupled to the deeper mixed layer, which lead to intensified vertical mixing in the winter61, are likely to carry CO2-rich waters to the surface layer of the strait (Fig. 8b). Indeed, this has been the process most observed in other Southern Ocean coastal regions8,11,24. On the western Antarctic Peninsula shelf, for example, there is no evidence of inorganic macronutrient regeneration in late summer, revealing that the increase in CT must be more associated with upwelling and/or advection processes18. Although these mCDW intrusions can occur throughout the year and through virtually all connections of the Gerlache Strait36,42,43, they are expected to be more intense in winter61 and at the southern end of the strait62. In addition, the rejection of CT through sea ice brine63,64 is an important process (Fig. 8b). Despite occurring more intensely in winter than in other seasons, this process should also contribute to CO2 release in autumn, as it was also dominant in controlling AT and CT (Fig. 3c). The increase in CT due to ice growth, first shown in a laboratory experiment63, occurs in both Arctic and Antarctic regions, where there is an intense sea ice dynamic64. Hence, the increase in CT leads to high pCO2sw values but is also related to decreases in ΩCa and ΩAr65. Thus, these conditions contribute to maintaining a relatively low pH (≤ 8.00) until mid-spring, when sea ice begins to melt and both CT and pCO2sw decrease towards the summer season.

Although the spatial distribution of FCO2 is more homogeneous in autumn and winter than in other seasons (Fig. 7), there is intense interannual variability in these fluxes (Fig. 6). It is not yet clear what drives this variability, but it has been linked to sea ice cover variability in other Antarctic regions8,13,66. This link makes sense due to the good correlation (r2 = 0.73; p = 0.0006; n = 12) of the FCO2 seasonal cycle with the sea ice cover seasonality in the Gerlache Strait, mainly in the months when it acts as a CO2 source (r2 = 0.93; p = 0.0136; n = 7) (Figure S10). Despite the strong CO2 outgassing during these periods, sea ice cover constrains sea-air CO2 exchanges8,26, leading to the conclusion that this CO2 outgassing could be even more intense under sea ice-free conditions, as observed in the Arctic Ocean67. Hence, the FCO2 dynamics in sea ice-covered periods may be more sensitive than previously thought.

Seasonality of the carbonate system and acidification process

The carbonate system parameters on the surface of the strait follow seasonal FCO2 dynamics, that is, sea ice dynamics. The lower pH, ΩCa and ΩAr values in winter than in other seasons, although expected, reinforce the biogeochemical sensitivity of this season. The low temperatures and the brine released by sea ice growth lead to the dissolution of calcium carbonate and decreases in ΩCa and ΩAr19. However, we did not find the calcium carbonate in the surface of the Gerlache Strait to be in a subsaturated state, even in winter when there was high pCO2sw; this was also the case in Ryder Bay18,19, a region located farther south on the western Antarctic Peninsula shelf, which is under dynamic conditions similar to those of the Gerlache Strait. In summer, carbonate mineral supersaturation is associated with regions where there is strong CO2 uptake, such as in the southernmost portion of the strait, where meteoric water input is most intense (Figure S9) and salinity is relatively low (Figures S4 and S7). This reveals that the intense pCO2sw drawdown caused by biological activity outweighs the increase in pCO2sw by the effect of carbonate precipitation18, and carbonate dissolution is minimized due to the biological uptake of CT. Nevertheless, the sensitivity of these parameters should be observed in more detail, as carbonate calcification and dissolution processes also seem to play an important role in controlling AT and CT (Fig. 3b,c). Furthermore, because we found minimum pH values in winter (7.92) lower than those at Ryder Bay in 1994 (8.11) and 2010 (8.00)7 as well as between 2011 and 2014 (7.95)19, these waters may be experiencing ocean acidification, although counterintuitive processes may be offsetting the effects in the studied region22. In fact, the waters of the Gerlache Strait have previously been reported to show signs of acidification in summer below the mixed layer20,22, with surface pH values lower than those found at Ryder Bay (8.21–8.4818).

The effects of intensified summer CO2 uptake on calcite and aragonite saturation in surface waters may emerge in the coming years. However, supersaturation of these carbonate species is associated with decreased pCO2sw values in summer15. This reveals that these feedback effects need to be further investigated, especially considering the residence time of these waters in coastal regions. As strong summer CO2 sink periods are extended, an inverse effect of sea surface acidification may occur, as observed in the southernmost portion of the Gerlache Strait. Nevertheless, the acidification process should occur in the deep layers of these strong CO2 sink regions and in adjacent deep waters due to horizontal advection. Indeed, this will likely be the case because the residence time of surface waters in this region was estimated to be less than 7 days, while the residence time in adjacent larger basins ranges between 13 and 40 days50. Therefore, assuming a steady increase in both atmospheric CO268 and temperature69, the Southern Ocean coastal regions may become intense hotspots of deep-ocean acidification, with some expected implications for organisms throughout the water column and the food web as a whole. For example, on the sea surface, there may be a restructuring of the food web due to a shift in the dominant groups of phytoplankton, such as from diatoms to smaller organisms [Refs.24,53 and references therein]. Such changes will potentially decrease the transfer of carbon, energy and nutrients through organisms such as diatoms to pelagic and benthic ecosystems, with complex feedbacks on ocean biogeochemistry and climate24. In this sense, these findings shed light on the importance of clarifying the real impacts of these changes throughout the water column. This is because, despite showing signs of acidification, most studies provide only snapshots, and coupled ocean–land–ice processes can mask the real ocean acidification state of Southern Ocean coastal regions.

Annual budget of sea-air CO2 exchanges

We have identified the Gerlache Strait as a weak CO2 source from 2002 to 2017, with an annual budget of sea-air CO2 exchanges at near-equilibrium conditions. This contrasts with the expectations for other Antarctic coastal regions, which demonstrate annual CO2 sink behaviour5,13,25, such as in summer and spring11,14,33. The studied region acts as a moderate CO2 source in autumn and a strong CO2 source in winter. The CO2 outgassing that occurs during 8 months of the year (i.e., from April to November) is almost fully compensated for in only 4 months (i.e., from December to March), when the region acts as a moderate to strong CO2 sink. Although this behaviour is not considered typical for Antarctic coastal regions, the Gerlache Strait lies at approximately 64°S, where Takahashi et al.70 verified an approximately neutral annual sea-air CO2 flux. Nevertheless, here, we hypothesize that this scenario is more common to coastal regions of the Southern Ocean than previously thought because incipient signs of this behaviour have already been identified in other Antarctic coastal regions. For example, Bakker et al.26 found strong supersaturation of seawater CO2 relative to atmospheric CO2 in autumn and winter in the Weddell Sea but suggested that the region was an annual CO2 sink. These contrasting summer/winter behaviours, with an annual CO2 sink budget, also extend to other Southern Ocean coastal regions, such as the western Antarctic Peninsula5,7,8,11, the Ross Sea13, the Indian Antarctic sector6,71 and even the Antarctic Zone south of 62°S as a whole72. However, the relatively low monthly and interannual coverage in most of these studies may have biased the integrated FCO2 budget throughout the year. This is particularly true if we take into account recent estimates of FCO2 from long-term climatology for global coastal regions4. In this climatology, the NAP, as well as the Weddell Sea and much of the Atlantic and Indian sectors of the Southern Ocean, was a net CO2 source between 1998 and 2015. Despite this, the CO2 uptake by CO2 sink regions was so intense that the annual FCO2 budget for this period was approximately − 17 Tg C year–14.

Expected scenarios for the future of sea-air CO2 exchanges

The recent changes observed in the NAP, mainly related to the intensification of the westerly winds49, rising temperatures73 and the prolongation of ice-free water periods74,75, are expected to persist in the coming years24,28. In this sense, two future scenarios for net sea-air CO2 fluxes can be projected. First, with longer ice-free water periods, these coastal regions could release CO2 that would otherwise remain in the seawater isolated by sea ice, intensifying the annual CO2 source. This release may be enhanced by intensified mCDW intrusion into the western Antarctic Peninsula shelf that have been projected24,45, although little is known about its periodicity and variability. On the other hand, nutrient-rich mCDW intrusions coupled with the delayed sea ice cover period and rising temperatures should lead to prolonged phytoplankton growth75. Thus, strong CO2 sink periods should also extend beyond late summer. As CO2 uptake has intensified in the summer14,15 and proved to nearly counteract annual CO2 evasion, this region could become an annual CO2 sink in future years, particularly assuming that the Southern Ocean is becoming greener75. Actually, this second scenario seems likely to occur, as the magnitude and frequency of FCO2 in months when the region is a strong CO2 sink are increasing and in months when the region is a strong CO2 source have been less frequent (Fig. 5), leading to intensified annual CO2 uptake since 2010 (Fig. 6a).

These scenarios become more complex when we take into account the influence of the modes of climate variability. For example, the positive phase of SAM has been associated with more intense CO2 outgassing due to the deepening of the mixed layer76. Conversely, it was also associated with higher CO2 uptake due to the intensification of upwelling, which supplies iron and nutrients to the sea surface and hence increases phytoplankton growth77. This reveals the sensitivity of sea-air CO2 exchanges to these feedback mechanisms and the urgent need to broaden investigations for a coupled analysis of ocean-climate systems. Nevertheless, signs of intensifying summer CO2 sink behaviour14,15 suggest that the influence of SAM should be reversing the flux to encourage annual net CO2 uptake in Antarctic coastal regions.

Methods

Dataset and carbonate system properties

We used the data available from Surface Ocean CO2 Atlas version 6 (SOCATv6)78 to compile a temporal series spanning 2002 to 2017 (Figure S2) of the sea surface (up to a depth of 5 m) temperature (SST), salinity (SSS) and seawater CO2 partial pressure (pCO2sw) of the Gerlache Strait. Here, we evaluated the seasonal variability of the net sea-air CO2 flux (FCO2) and hydrographic and carbonate system parameters. Therefore, the seasons were defined as (1) summer: January to March; (2) autumn: April to June; (3) winter: July to September; and (4) spring: October to December. We analysed the months in which the data covered the majority of the Gerlache Strait in all seasons (Figure S3).

The pCO2sw data extracted from SOCATv6 were directly measured using air–water equilibrators and an infrared analyser for CO2 quantification78. However, SOCATv6 provides surface pCO2sw data with only corresponding SST and SSS values. Hence, we used total alkalinity (AT) from the High Latitude Oceanography Group (GOAL)79 and the World Data Center PANGAEA80 to estimate AT from SSS using Eq. 1 (r2 = 0.98, RMSE = 4.4, n = 140).

These data were sampled in the austral summers of 1995/96 (PANGAEA; https://doi.pangaea.de/10.1594/PANGAEA.825645;81) and 2015–2019 (GOAL; Table S1;15,22). Equation 1 was developed using the curve fitting toolbox of MATLAB, with the least absolute residual mode and first-order polynomial adjustment. This option considered all the data important, minimized the residuals, and can be used when data series have few nonconfigurable values82. Using the estimated AT and pCO2sw from SOCATv6, we calculated the total dissolved inorganic carbon (CT), pH and saturation states of calcite (ΩCa) and aragonite (ΩAr) with CO2SYS version 2.183,84. This program determines these parameters from the thermodynamic equilibrium relation between the carbonate species using carbonate dissociation constants. Because of the good response obtained in high-latitude regions14, 15,20,85,86, we used the constants K1 and K2 proposed by Goyet and Poisson87 and the sulphate and borate constants proposed by Dickson88 and Uppström89, respectively.

Drivers of pCO2 sw changes

The pCO2sw drivers throughout the seasons were calculated based on the difference between the values of the parameters in each season and their respective averages in previous seasons (ΔpCO2drv; Table 1). Then, the ΔpCO2drv values were separated into categories representing the contributions of differences in CT, AT, SST and SSS. The relative contributions of the drivers changing pCO2sw were assessed by converting their relative changes into pCO2sw units (μatm) following Lenton et al.55 as in Eq. 2:

where ΔCT, ΔAT, ΔSST and ΔSSS are the differences between the values of the parameters and their respective averages in previous seasons. This analysis was conducted in each year, and the results were averaged to represent an average year. The partial derivatives were calculated using Eqs. 3 to 6 (see details in Takahashi et al.3). These approximations have been widely used in the Southern Ocean12,21,51 to evaluate pCO2sw drivers, both seasonally and spatially. Here, we used the average Revelle and Alkalinity factors of 14 and − 13, respectively.

Net sea-air CO2 flux (FCO2)

We calculated FCO2 using Eq. 74, 90:

where ∆pCO2 is the difference between pCO2sw and atmospheric pCO2 (pCO2air); Kt is the gas transfer velocity, depending on wind speed91; Ks is the CO2 solubility coefficient, as a function of both SST and SSS92; and Ice is a dimensionless coefficient corresponding to the fraction of the air–water interface (between 0 and 1) covered by sea ice. We used monthly averages of pCO2air and wind speed (m s–1) data from the U.S. Palmer Station, located in the southern part of the Gerlache Strait. The station continuously measures meteorological parameters throughout the year68. We calculated pCO2air from the monthly averages of the atmospheric molar fraction of CO2 (xCO2air) and atmospheric pressure (both from the Palmer Station), which was corrected by the water vapour pressure estimated from SST and SSS by the widely used equations of Weiss and Price93. Sea ice cover was obtained from the monthly mean of the 0.25° daily satellite products by Reynolds et al.94, which cover the entire length of the Gerlache Strait (Figure S9e–h).

Spatial distributions of properties

All spatial distribution maps for the properties in this study were interpolated using Data-Interpolating Variational Analysis (DIVA) gridding95. We used a length scale value of 15‰ for both the X and Y axes to ensure optimal preservation of data structure and smoothness. The averaging and all other calculations performed in this study were based only on the observed or reconstructed data and not on the interpolated data. Map interpolations were made to provide reader-friendly visualization of the results.

Limitations and uncertainties

We estimated the propagated uncertainty from the partial derivatives of all calculated parameters (Table 2) in relation to each variable involved in the calculation as follows:

where the derived functions \(f(x)\) are the calculated parameters (i.e., FCO2, CT, Ω and pH) and σ is the uncertainty associated with each variable involved in calculation of the parameter. Because SSS uncertainties are expected to be low enough to be negligible (i.e., < 0.001, according to the GOAL and PANGAEA datasets), they were not considered here. Hence, the propagated uncertainties in CT, Ω and pH fundamentally represented the errors associated with the estimated AT (± 4.4 μmol kg–1), SST (± 0.05 °C) and measured pCO2sw. We used pCO2sw data from SOCATv6 with uncertainties < 2 µatm (55% of total) and < 5 µatm (45%). We calculated the propagated uncertainties for all carbonate system properties with the CO2SYS error tool96. For FCO2, uncertainty was related to the standard error of the averaged wind speed for each season, the measured pCO2sw and xCO2air, and sea ice cover. The analytical error for xCO2air measurements from the U.S. Palmer Station was estimated to be ± 0.07 µmol/mol for the studied period68. Sea ice concentrations were computed to a precision of 1% coverage94,97.

Finally, we used a first-order polynomial relationship between AT and SSS to estimate AT and calculate the other parameters of the carbonate system based on summertime data. We assumed this relationship for all seasons because the summer was the only period with available AT data for the study region. However, the summer is characterized by greater AT variability than other seasons, implying that the ranges of AT and SSS may represent the annual range (i.e., AT: 2200–2320 μmol kg−1; SSS: 32–34.5). Such limitations are mainly due to the scarcity of data in periods other than summer and highlight the need for additional efforts to better understand the dynamics of the carbonate system parameters in coastal regions of the Southern Ocean.

Change history

09 December 2020

An amendment to this paper has been published and can be accessed via a link at the top of the paper.

References

Takahashi, T. et al. Climatological mean and decadal change in surface ocean pCO2, and net sea-air CO2 flux over the global oceans. Deep Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 56, 554–577 (2009).

Lenton, A. et al. Sea-air CO2 fluxes in the Southern Ocean for the period 1990–2009. Biogeosci. Discuss. 10, 285–333 (2013).

Takahashi, T. et al. Climatological distributions of pH, pCO2, total CO2, alkalinity, and CaCO3 saturation in the global surface ocean, and temporal changes at selected locations. Mar. Chem. 164, 95–125 (2014).

Roobaert, A. et al. The spatiotemporal dynamics of the sources and sinks of CO2 in the global coastal ocean. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles https://doi.org/10.1029/2019GB006239 (2019).

Gibson, J. A. E. & Trull, T. W. Annual cycle of fCO2 under sea-ice and in open water in Prydz Bay, East Antarctica. Mar. Chem. 66, 187–200 (1999).

Metzl, N., Bunet, C., Jabaud-Jan, A., Poisson, A. & Schauer, B. Summer and winter air–sea CO2 fluxes in the Southern Ocean. Deep Res. I 53, 1548–1563 (2006).

Roden, N. P., Shadwick, E. H., Tilbrook, B. & Trull, T. W. Annual cycle of carbonate chemistry and decadal change in coastal Prydz Bay, East Antarctica. Mar. Chem. 155, 135–147 (2013).

Legge, O. J. et al. The seasonal cycle of ocean-atmosphere CO2 flux in Ryder Bay, West Antarctic Peninsula. Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 2934–2942 (2015).

Cavalieri, D. J. & Parkinson, C. L. Antarctic sea ice variability and trends, 1979–2006. J. Geophys. Res. 113, C07004 (2008).

Parkinson, C. L. & Cavalieri, D. J. Antarctic sea ice variability and trends, 1979–2010. Cryosphere 6, 871–880 (2012).

Karl, D. M., Tilbrook, B. D. & Tien, G. Seasonal coupling of organic matter production and particle flux in the western Bransfield Strait, Antarctica. Deep-Sea Res. 38, 1097–1126 (1991).

Takahashi, T., Olafsson, J., Goddard, J. G., Chipman, D. W. & Sutherland, S. C. Seasonal variation of CO2 and nutrients in the high-latitude surface oceans: a comparative study. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 7, 843–878 (1993).

Arrigo, K. R. & Van Dijken, G. L. Interannual variation in air-sea CO2 flux in the Ross Sea, Antarctica: a model analysis. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 112, 1–16 (2007).

Brown, M. S. et al. Enhanced oceanic CO2 uptake along the rapidly changing West Antarctic Peninsula. Nat. Clim. Change 9, 678–683 (2019).

Monteiro, T., Kerr, R., Orselli, I. B. M. & Lencina-Avila, J. M. Towards an intensified summer CO2 sink behaviour in the Southern Ocean coastal regions. Prog. Oceanogr. 183, 102267 (2020).

Caetano, L. S. et al. High-resolution spatial distribution of pCO2 in the coastal Southern Ocean in late spring. Antarct. Sci. 1, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954102020000334 (2020).

Nomura, D. et al. Winter-to-summer evolution of pCO2 in surface water and air–sea CO2 flux in the seasonal ice zone of the Southern Ocean. Biogeosciences 11, 5749–5761 (2014).

Jones, E. M. et al. Ocean acidification and calcium carbonate saturation states in the coastal zone of the West Antarctic Peninsula Peninsula. Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 139, 181–194 (2017).

Legge, O. J. et al. The seasonal cycle of carbonate system processes in Ryder Bay, West Antarctic Peninsula. Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 139, 167–180 (2017).

Kerr, R. et al. Carbonate system properties in the Gerlache Strait, Northern Antarctic Peninsula (February 2015): I. Sea-air CO2 fluxes. Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 149, 171–181 (2018).

Kerr, R. et al. Carbonate system properties in the Gerlache Strait, Northern Antarctic Peninsula (February 2015): II. Anthropogenic CO2 and seawater acidification. Deep Res. Part II 149, 182–192 (2018).

Lencina-Avila, J. M. et al. Past and future evolution of the marine carbonate system in a coastal zone of the Northern Antarctic Peninsula. Seep Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 149, 193–205 (2018).

Dejong, H. B. & Dunbar, R. B. Air-sea CO2 exchange in the Ross Sea, Antarctica. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean 122, 8167–8181 (2017).

Henley, S. F. et al. Variability and change in the west Antarctic Peninsula marine system: research priorities and opportunities. Prog. Oceanogr. 173, 208–237 (2019).

Lenton, A., Matear, R. J. & Tilbrook, B. Design of an observational strategy for quantifying the Southern Ocean uptake of CO2. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 20, GB4010 (2006).

Bakker, D. C. E., Hoppema, M., Schröder, M., Geibert, W. & de Baar, H. J. W. A rapid transition from ice covered CO2–rich waters to a biologically mediated CO2 sink in the eastern Weddell Gyre. Biogeosciences 5, 1373–1386 (2008).

Arrigo, K. R., van Dijken, G. & Long, M. Coastal Southern Ocean: a strong anthropogenic CO2 sink. Geophys. Res. Lett. 35, 1–6 (2008).

Kerr, R., Mata, M. M., Mendes, C. R. B. & Secchi E. R. Northern Antarctic Peninsula: a marine climate hotspot of rapid changes on ecosystems and ocean dynamics. Deep Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 149, 4–9 (2018).

Nowacek, D. P. et al. Super-aggregations of Krill and Humpback Whales in Wilhelmina Bay, Antarctic Peninsula. PLoS ONE 6, e19173 (2011).

Dalla Rosa, L. et al. Movements of satellite-monitored humpback whales on their feeding ground along the Antarctic Peninsula. Polar Biol. 31, 771–781 (2008).

Mendes, C. R. B. et al. New insights on the dominance of cryptophytes in Antarctic coastal waters: a case study in Gerlache Strait. RDeep Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 149, 161–170 (2018).

Costa, R. R. et al. Dynamics of an intense diatom bloom in the Northern Antarctic Peninsula, February 2016. Limnol. Oceanogr. 66, 1–20 (2020).

Ito, R. G., Tavano, V. M., Mendes, C. R. B. & Garcia, C. A. E. Sea-air CO2 fluxes and pCO2 variability in the Northern Antarctic Peninsula during 3 summer periods (2008–202010). Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 149, 84–98 (2018).

Kim, H. et al. Inter-decadal variability of phytoplankton biomass along the coastal West Antarctic Peninsula. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 376(2122), 20170174 (2018).

Secchi, E. R. et al. Encounter rates and abundance of humpback whales (Megaptera novaeangliae) in Gerlache and Bransfield Straits, Antarctic Peninsula. J. Cetacean Res. Manag. 3, 107–111 (2011).

Prézelin, B. B., Hofmann, E. E., Mengelt, C. & Klinck, J. M. The linkage between upper circumpolar deep water (UCDW) and phytoplankton assemblages on the west Antarctic Peninsula continental shelf. J. Mar. Res. 58, 165–202 (2000).

Wadham, J. L. et al. Ice sheets matter for the global carbon cycle. Nat. Commun. 10, 3567 (2019).

Meredith, M. P. & King, J. C. Rapid climate change in the ocean west of the Antarctic Peninsula during the second half of the 20th century. Geophys. Res. Lett. 32, 1–5 (2005).

Moreau, S. et al. Climate change enhances primary production in the western Antarctic Peninsula. Glob. Change Biol. 21, 2191–2205 (2015).

da Cunha, L. C. et al. Contrasting end-summer distribution of organic carbon along the Gerlache Strait, Northern Antarctic Peninsula: Bio-physical interactions. Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 149, 206–217 (2018).

Avelina, R. et al. Contrasting dissolved organic carbon concentrations in the Bransfield Strait, northern Antarctic Peninsula: insights into Enso and Sam effects. J. Marine Syst. In press (2020)

Smith, D. A., Hofmann, E. E., Klinck, J. M. & Lascara, C. M. Hydrography and circulation of the West Antarctic Peninsula continental shelf. Deep. Res. Part I 46, 925–949 (1999).

García, M. A. et al. Water masses and distribution of physico-chemical properties in the Western Bransfield Strait and Gerlache Strait during Austral summer 1995/96. Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 49, 585–602 (2002).

Couto, N., Martinson, D. G., Kohut, J. & Schofield, O. Distribution of upper circumpolar deep water on the warming continental shelf of the West Antarctic Peninsula. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 122, 5306–5315 (2017).

Barllet, E. M. R. et al. On the temporal variability of intermediate and deep waters in the Western Basin of the Bransfield Strait. Deep Sea Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 149, 31–46 (2018).

Cape, M. R. et al. Circumpolar deep water impacts glacial meltwater export and coastal biogeochemical cycling along the West Antarctic Peninsula. Front. Mar. Sci. 6, 144 (2019).

Venables, H. J., Meredith, M. P. & Brearley, A. Modification of deep waters in Marguerite Bay, western Antarctic Peninsula, caused by topographic overflows. Deep Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 139, 9–17 (2017).

Stammerjohn, S. E., Martinson, D. G., Smith, R. C., Yuan, X. & Rind, D. Trends in Antarctic annual sea ice retreat and advance and their relation to El Ninño-Southern Oscillation and Southern Annular Mode variability. J. Geophys. Res. 113, C03S90 (2008).

Dinniman, M. S., Klinck, J. M. & Hofmann, E. E. Sensitivity of circumpolar deep water transport and ice shelf basal melt along the West Antarctic Peninsula to changes in the winds. J. Clim. 25, 4799–4816 (2012).

Zhou, M., Niiler, P. P. & Hu, J. H. Surface currents in the Bransfield and Gerlache Straits, Antarctica. Deep Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 49, 267–280 (2002).

Dotto, T. S., Kerr, R., Mata, M. M. & Garcia, C. A. E. Multidecadal freshening and lightening in the deep waters of the Bransfield Strait, Antarctica. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans. 121, 3741–3756 (2016).

Alvarez, M., Ríos, A. F. & Rosón, G. Spatio-temporal variability of air–sea fluxes of carbon dioxide and oxygen in the Bransfield and Gerlache Straits during. Dee. Res. 49, 643–662 (2002).

Mendes, C. R. B. et al. Shifts in the dominance between diatoms and cryptophytes during three late summers in the Bransfield Strait (Antarctic Peninsula). Polar Biol. 36, 537–547 (2013).

Mendes, C. R. B. et al. Impact of sea ice on the structure of phytoplankton communities in the northern Antarctic Peninsula. Deep Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 149, 111–123 (2018).

Lenton, A. et al. The observed evolution of oceanic pCO2 and its drivers over the last two decades. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 26, 1–14 (2012).

Zeebe, R. E. History of seawater carbonate chemistry, atmospheric CO2 and ocean acidification. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 40, 141–165 (2012).

Lancelot, C., Mathot, S., Veth, C. & de Baar, H. Factors controlling phytoplankton ice-edge blooms in the marginal ice-zone of the northwestern Weddell Sea during sea ice retreat 1988: field observations and mathematical modelling. Polar Biol. 13, 377–387 (1993).

Santoso, A., Mcphaden, M. J. & Cai, W. The Defining Characteristics of ENSO extremes and the Strong 2015/2016 El Niño. Rev. Geophys. 55, 1079–1129 (2017).

Moffat, C., Owens, B. & Beardsley, R. C. On the characteristics of circumpolar deep water intrusions to the west Antarctic Peninsula continental shelf. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 114, 1–16 (2009).

Moffat, C. & Meredith, M. Shelf–ocean exchange and hydrography west of the Antarctic Peninsula: a review. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 376, 20170164 (2018).

Venables, H. J. & Meredith, M. P. Feedbacks between ice cover, ocean stratification, and heat content in Ryder Bay, western Antarctic Peninsula. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 119, 5323–5336 (2014).

Parra, R. R. T., Laurido, A. L. C. & Sánchez, J. D. I. Hydrographic conditions during two austral summer situations (2015 and 2017) in the Gerlache and Bismarck straits, northern Antarctic Peninsula. Deep Res. Part I 161, 103278 (2020).

Nomura, D., Inoue, H. Y. & Toyota, T. The effect of sea-ice growth on air-sea CO2 flux in a tank experiment. Tellus 58B, 418–426 (2006).

Rysgaard, S. et al. Sea ice contribution to the air–sea CO2 exchange in the Arctic and Southern Oceans. Tellus 63B, 823–830 (2011).

Hauri, C. et al. Two decades of inorganic carbon dynamics along the West Antarctic Peninsula. Biogeosciences 12, 6761–6779 (2015).

Keppler, L. & Landschützer, P. Regional wind variability modulates the Southern Ocean carbon sink. Sci. Rep. 9, 7384 (2019).

Ouyang, Z. et al. Sea-ice loss amplifies summertime decadal CO2 increase in the western Arctic Ocean. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 678–684 (2020).

Dlugokencky, E. J., Lang, P. M., Masarie, K. A., Crotwell, A. M. & Crotwell, M. J. 2015. Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide Dry Air Mole Fractions from the NOAA ESRL Carbon Cycle Cooperative Global Air Sampling Network, 1968–2014, Version: 2015–09–08, ftp://aftp.cmdl.noaa.gov/data/trace_gases/co2/flask/surface.

Turner, J. et al. Antarctic climate change and the environment: an update. Polar Rec. 50, 237–259 (2014).

Takahashi, T. et al. The changing carbon cycle in the Southern Ocean. Oceanography 25, 26–37 (2012).

Metzl, N. et al. Spatio-temporal distributions of air-sea fluxes of CO2 in the India and Antarctic oceans. Tellus 47B, 56–69 (1995).

McNeil, B. I., Metzl, N., Key, R. M., Matear, R. J. & Corbiere, A. An empirical estimate of the Southern Ocean air-sea CO2 flux. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 21, GB3011 (2007).

Siegert, M. et al. The Antarctic Peninsula under a 1.5°C global warming scenario. Front. Environ. Sci. 7, 102 (2019).

Shepherd, A. et al. Mass balance of the Antarctic ice sheet from 1992 to 2017. Nature 558, 219–226 (2018).

Del Castillo, C. E., Signorini, S. R., Karaköylü, E. M. & Rivero-Calle, S. Is the Southern Ocean getting greener?. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 6034–6040 (2019).

Lovenduski, N. S., Gruber, N., Doney, S. C. & Lima, I. D. Enhanced CO2 outgassing in the Southern Ocean from a positive phase of the Southern annular mode. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 21, GB2026 (2007).

Hauck, J. et al. Seasonally different carbon flux changes in the Southern Ocean in response to the southern annular mode. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 27, 1236–1245 (2013).

Bakker, D. C. E. et al. A multi-decade record of high-quality fCO2 data in version 3 of the Surface Ocean CO2 Atlas (SOCAT). Earth Syst. Sci. Data 8, 383–413 (2016).

Mata, M. M., Tavano, V. M. & García, C. A. E. 15 years sailing with the Brazilian High Latitude Oceanography Group (GOAL). Deep Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 149, 1–3 (2018).

Hellmer, H. H. & Rohardt, G. Physical oceanography during Ary Rongel cruise AR01. Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Center for Polar and Marine Research, Bremerhaven. PANGAEA https://doi.org/10.1594/PANGAEA.735276 (2010).

Anadón, R. & Estrada, M. The FRUELA cruises: a carbon flux study in productive areas in the Antarctic Peninsula (December 1995–January 1996). Deep Sea Res. II 49, 567–583 (2002).

Patil, G. P. & Rao, C. R. Handbook of Statistics v 12 927 (Amsterdan, Environmental Statistics, 1994).

Lewis, E., Wallace, D. & Allison, L. J. Program Developed for CO2 System Calculations System Calculations 38 (Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center, USA, 1998).

Pierrot, D., Lewis, E. & Wallace, D. W. R. MS Excel Program Developed for CO2 System Calculations, ORNL/CDIAC-105a (Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center. Oak Ridge National Laboratory, U.S. Department of Energy, Tennessee, 2006).

Millero, F. J. et al. Dissociation constants for carbonic acid determined from field measurements. Deep Res. Part I 49, 1705–1723 (2002).

Laika, H. E. et al. Interannual properties of the CO2 system in the Southern Ocean south of Australia. Antarct. Sci. 21, 663 (2009).

Goeyt, C. & Poisson, A. New determination of carbonic acid dissociation constants in seawater as a function of temperature and salinity. Deep Sea Res. Part A Ocean Res. Pap. 36, 1635–1654 (1989).

Dickson, A. G. Thermodynamics of the dissociation of boric acid in synthetic seawater from 273.15 to 318.15 K. Deep Sea Res. 37, 755–766 (1990).

Uppström, L. R. Boron/chlorinity ratio of deep-sea water from the Pacific Ocean. Deep Sea Res. 21, 161–162 (1974).

Deacon, E. L. Gas transfer to and across an air–water interface. Tellus 29(4), 363–374. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2153-3490.1977.tb00724.x (1977).

Wanninkhof, R. Relationship between wind speed and gas exchange over the ocean revisited. Limnol. Oceanogr. Methods 12, 351–362 (2014).

Weiss, R. F. Carbon dioxide in water and seawater: the solubility of a non-ideal gas. Mar. Chem. 2, 203–215 (1974).

Weiss, R. & Price, B. Nitrous oxide solubility in water and seawater. Mar. Chem. 8(4), 347–359. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4203(80)90024-9 (1980).

Reynolds, R. W. et al. Daily high-resolution-blended analyses for sea surface temperature. J. Clim. 20(22), 5473–5496. https://doi.org/10.1175/2007JCLI1824.1 (2007).

Troupin, C. et al. Generation of analysis and consistent error fields using the data interpolating variational analysis (Diva). Ocean Model. 52–53, 90–101 (2012).

Orr, J. C., Epitalon, J., Dickson, A. & Gattuso, J. Routine uncertainty propagation for the marine carbon dioxide system. Mar. Chem. 207, 84–107 (2018).

Grumbine, R. W. Automated passive microwave sea ice concentration analysis at NCEP. NOAA Tech. Note 120, 13 pp. 1996. [Available from NCEP/NWS/NOAA, 5200 Auth Road, Camp Springs, MD 20746.]

Savidge, D. K. & Amft, J. A. Circulation on the West Antarctic Peninsula derived from 6 years of shipboard ADCP transects. Deep Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 56, 1633–1655 (2009).

Friis, K., Körtzinger, A. & Wallace, D. W. R. The salinity normalization of marine inorganic carbon chemistry data. Geophys. Res. Lett. 30(2), 1085. https://doi.org/10.1029/2002GL015898 (2003).

Schlitzer, R. Ocean Data View, v. 5.3.0, https://odv.awi.de (2018).

Acknowledgements

This study contributes to the activities of the Brazilian Ocean Acidification Network (BrOA; www.broa.furg.br) and the Brazilian High Latitude Oceanography Group (GOAL; www.goal.furg.br), which is part of the Brazilian Antarctic Program (PROANTAR). GOAL has been funded by and/or has received logistical support from the Brazilian Ministry of the Environment (MMA), the Brazilian Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation (MCTI), the Brazilian Navy, the Secretariat of the Interministerial Commission for the Resources of the Sea (SECIRM), and the Council for Research and Scientific Development of Brazil (CNPq) through grants from the Brazilian National Institute of Science and Technology of Cryosphere (INCT-CRIOSFERA; CNPq Grants Nos. 573720/2008-8 and 465680/2014-3; FAPERGS Grant no. 17/2551-0000518-0), NAUTILUS, INTERBIOTA, PROVOCCAR and ECOPELAGOS projects (CNPq Grants Nos. 405869/2013-4, 407889/2013-2, 442628/2018-8 and 442637/2018-7, respectively), and Higher Education Personnel Improvement Coordination (CAPES Grant No. 23038.001421/2014-30). T.M. received financial support from PhD Grant No. 88887.360799/2019-00 from CAPES. R.K. received financial support from researcher Grant No. 304937/2018-5 from CNPq and 888881.195000/2018-01 from CAPES. We are thankful for the resources provided by CAPES to support the Graduate Program in Oceanology. We appreciate the availability of high-quality data from the SOCATv6, PANGAEA and Palmer Station datasets. Special thanks to the scientists (Taro Takahashi, Colm Sweeney, David Munro, Stu Sutherland, Timothy Newberger, Steven van Heuven, Mario Hoppema, Vassilis Kitidis and Ian Brown) onboard the RV Lawrence M. Gould, Nathaniel B. Palmer, Polarstern and James Clark Ross, who provided the surface ocean pCO2 measurements publicly available via the SOCAT dataset. We thank all researchers and students from LEOC/FURG and other GOAL groups for their contributions to cruise planning, sampling, and analyses. We also thank the Brazilian Navy, especially the crew onboard the RV Almirante Maximiano, for providing logistical and sampling support during the NAUTILUS and INTERBIOTA cruises.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.M. conducted the data analysis and main interpretations of this study as part of his PhD. thesis. R.K. supervised T.M. in conducting this study. He also planned and was the PI onboard the GOAL cruises. E.M. contributed as an expert in carbonate system and biogeochemical processes. All authors contributed to the interpretation of results and writing the manuscript as experts on marine CO2 systems.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Monteiro, T., Kerr, R. & Machado, E.d. Seasonal variability of net sea-air CO2 fluxes in a coastal region of the northern Antarctic Peninsula. Sci Rep 10, 14875 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-71814-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-71814-0

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.