Abstract

Exact solutions of a novel quasi-relativistic quantum mechanical wave equation are found for Hydrogen-like atoms. This includes both, an exact analytical expression for the energies of the bound states, and exact analytical expressions for the wavefunctions, which successfully describe quantum particles with mass and spin-0 up to energies comparable to the energy associated to the mass of the particle. These quasi-relativistic atomic orbitals may be used for improving ab-initio software packages dedicated to numerical simulations in physical-chemistry and atomic and solid-state physics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Wavefunctions of Hydrogen-like atoms, which are obtained by solving the Schrödinger equation1,2,3,4,5, are often used in ab-initio quantum mechanics simulations6,7,8.

For instance, there are plotted two probability functions (P(r)) in Fig. 1. P(r) were calculated using the following expression:

In Fig. 1, Rn,l(r) = R2,1,Sch(r) is the radial part of the solution of the Schrödinger equation for Hydrogen-like atoms1,2,3,4,5:

In Eq. (2), ℏ is the Plank constant (h) divided by 2π, m is the mass of the quantum particle, and U(r) is the Coulomb potential1,2,3,4,5:

In Eq. (3), e is the electron charge, Z is the atomic number, and εo is the electric permittivity of vacuum. P(r) gives the probability to find the electron inside of a hollow spherical shell of radius r and thickness Δr. In both cases (Z = 1 and 100), it was assumed that the electron is in a quantum state with principal quantum numbers n = 2 and orbital quantum number l = 11,2,3,4. As seen in Fig. 1, the electron is more closely confined around the nucleus in the Hydrogen-like Fermium atom (Z = 100) than in the Hydrogen atom (Z = 1). However, when using for simulations wavefunctions obtained by solving the Schrödinger equation, one should be aware of the limitations of this description. The Schrödinger equation is not Lorentz invariant9; therefore, it should only be used for atomic simulations when the electron has energies much smaller that the energy associated to his mass10,11,12,13. The energies of the electron in Hydrogen-like atoms, calculated using the Schrödinger equation, are given by the following expression1,2,3,4,5:

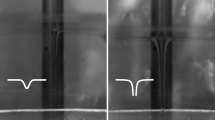

In Eq. (4), μ = (memn)/(me + mn) is the electron’s reduced mass, and me and mn are the electron and nucleus masses, respectively. Using Eq. (4) and denoting with the symbol (c) the speed of the light in vacuum, one can then find that |Ę2,Sch|/μc2 ~ 10–5 and ~ 0.0666 for Z = 1 and 100, respectively. Consequently, one should expect that the probability function for Z = 1 plotted in Fig. 1 is a better approximation to reality than P(r) for Z = 100. This expectation is confirmed by the probability functions plotted in Fig. 2, where the probability function shown in Fig. 1b is superposed to the corresponding probability function calculated using the solutions of the following recently reported quasi-relativistic wave equation10,11,12,13:

Formally, Eq. (5) can be obtained by substituting 2 m in Eq. (2) by (γV + 1)m. The factor γV is found in many equations of the Einstein’s special theory of relativity, and depends on the ratio between the square of the particle’s speed (V2) and c214,15,16:

The quasi-relativistic wave equation (Eq. 5) successfully describes a particle of mass m moving at quasi-relativistic energies (Ę = K + U ~ mc2)10,11,12,13. Equation (5) implies that the relation between the particle’s kinetic energy (K) and its linear momentum (p) is the one required by the special theory of relativity10,11,12,13,14,15,16

This contrasts with the non-relativistic relation, K = p2/2 m, for a particle described by the Schrödinger equation1,2,3,4,5,10,11,12,13,14,15,16. It should be noted that everywhere in this work, Ę = K + U is called the energy or the quasi-relativistic energy of the particle. Ę is not the total relativistic energy of the particle (E), which is given by the following expression: E = Ę + mc210,11,12,13,14,15,16. Also, this work focuses on Hydrogen-like atoms; therefore, m = μ in Eqs. (2), (5), and (7). The electron energy when the Hydrogen’s electron is in the quantum state n = 2, l = 1 is much smaller than μc2. Consequently, the probability functions calculated using Eqs. (2) and (5) superpose to each other almost perfectly (not shown). However, as shown in Fig. 2, this does not happen for Z = 100. Ę2,Sch ~ − 0.0666 μc2 in the Hydrogen-like Fermium atom; at these energies, as shown in Fig. 2, the Schrödinger equation underestimate the confinement of the electron around the Fermium nucleus. The wavefunctions found solving Eq. (5) then allows for improving the calculation of P(r) at quasi-relativistic electron energies.

Previously, the quasi-relativistic wave equation has been solved, following the same mathematical steps required for solving the same problems using the Schrödinger equation, for a free particle10, confinement of a quantum particle in box10,12,13, reflection by a sharp quantum potential12, tunnel effect12, and the Hydrogen atom11,13. In this work, it is discussed how to find the quasi-relativistic wavefunctions which are solution of Eq. (5). We compare the quasi-relativistic wavefunctions found with the corresponding ones for the Schrödinger equation. It is shown that, due to the high similitude between Eqs. (2) and (5), exact analytical solutions of Eq. (5) can be found. Moreover, this can be done using the same mathematical techniques used for solving the Schrödinger equation and with no more difficulty. In atoms and molecules, the number of particles is constant. This is because the energies of the electrons in atoms and molecules are smaller than the energy associated to the electron’s mass. The energies of the external electrons in atoms and molecules are non-relativistic; therefore, the wavefunctions calculated solving the Schrödinger equation are adequate for conducting simulations involving these electrons. However, the internal electrons in heavy atoms have quasi-relativistic energies; therefore, the quasi-relativistic wavefunctions, which are discussed for the first time in this work, can be used for improving ab-initio quantum mechanics simulations involving the inner electrons of heavy atoms. This also can be done using the exact relativistic wavefunctions obtained solving the Dirac equation2,15,16. However, the Dirac equation and the Dirac’s (bispinor) wavefunctions are much more complex than Eq. (5) and its (scalar) wavefunctions2,15,16,17. Both, Eq. (5) and the Schrödinger equation, allow building a relatively simple and intuitive quantum theory of atoms and molecules, where the number of electrons is constant, and no positrons are involved. However, Eq. (5) provides the advantage of including the correct relation between K and p, without paying a heavy price in mathematical and theoretical complexity. In addition, the wavefunctions of Eq. (5) may be smoothly introduced in general courses of Quantum Mechanics for illustrating the consequences, for the quantum theory, resulting from the introduction on it of the basic ideas of the special theory of relativity. It should be remarked that the wavefunction in Eq. (5) is a scalar. This is because Eq. (5) does include the correct relativistic relation between K and p11,13, but does not include the electron spin. The Dirac equation includes exactly both the electron spin and the relativistic effects. This requires a bispinor wavefunction with 4 components2,15,16,17,18. However, there are approximated theories only requiring, for the description of the spin effects, spinor two-component wavefunctions2,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23. In this work, the attention is focused on the consequences resulting, from including the correct relativistic relation between K and p, for the quantum theory of Hydrogen-like atoms. The rest of this paper is organized in the following way. In the next section, for self-reliance purposes, a summary about solving Eq. (5) is presented. In addition, and for the first time, an equation given the exact analytical expression of the energy of the bounded states in Hydrogen-like atoms is presented. Then, in the following section, the analytical expressions of several quasi-relativistic wavefunctions are presented and compared with the corresponding wavefunctions for Eq. (2). Finally, the conclusions of this work are given in the “Conclusions”.

Solving the quasi-relativistic wave equation

Due to the high similitude between Eqs. (2) and (5), exact analytical solutions of Eq. (5), with U(r) given by Eq. (3), can be found following the same procedures needed for solving the Schrödinger equation for Hydrogen-like atoms1,4,11. Expressing in spherical coordinates the Laplace operator in Eq. (5) and looking for separated variables solutions of Eq. (5)1,4,11:

where Yl(m) are the spherical harmonic functions1,2,3,4,5. And:

In Eq. (10):

When the electron moves slowly (V2 < < c2) then γV ~ 1; therefore, Eq. (10) reduces to the radial equation for hydrogen-like atoms obtained using the Schrödinger equation4. If one wants to be able to solve Eq. (10), using the same techniques that are used for solving the Schrödinger’s radial equation for a hydrogen-like atoms, it is necessary to eliminate γV from Eq. (11) This can be done using the relativistic equation11,14:

Therefore:

One can then use Eq. (13) and introduce the following variables11:

In Eq. (14), α is the fine-structure constant15,16:

This allows for rewriting Eq. (10) in the following way11:

When ℏζ < < μc and α2Z2 < < 1, Eq. (17) reduces to the equation that is solved for the Hydrogen atom when using the Schrödinger equation4:

From Eq. (18) can be found that4:

Consequently, when ℏζ < < μc and α2Z2 < < 1, Eq. (4) can be obtained from Eqs. (14), (16), and (19)4. However, each of the three terms in the right side of Eq. (17) contains a different quasi-relativistic correction to the radial equation of Hydrogen-like atoms. Fortunately, the quasi-relativistic Eq. (17) can be solved as Eq. (18) was solved4,11. One can look for a solution of Eq. (17) of the following form11:

This allows expressing τ(ρ) as a finite power series in ρ4,11:

In Eq. (21), jmax = n − (l + 1) and11:

Evaluating Eq. (22) for j = jmax and making ajmax+1 = 0, one can obtain11:

In some cases, for heavy Hydrogen-like atoms with Z > > 1, the term inside the square root in Eq. (24) could be negative; in these cases, the approximation to the square root included in Eq. (24) should be used. Substituting ρo and ρ1 given by Eq. (14) in Eq. (23), solving the resulting equation for ζ, and using Eq. (16), produce an exact analytical expression for Ȩ, which now depends not only on the principal quantum number n, but also on the orbital quantum number l and Z11. This expression is given here for the first time:

In Eq. (25), Δ = Δ(l, Z) given by Eq. (24), and Ξ is given by the following expression :

Expressing Eq. (25) as a series in powers of α, and taking the first terms of the series up to α4, conduct exactly to the following approximated expression of Eq. (25):

In Eq. (27), Ęn,Sch given by Eq. (4) was rewritten as a function of α in the following way:

Therefore, as should be expected, when α2Z2/n2 < < 1, Eq. (25) reduces to Eq. (4). Moreover, Eq. (27) is exactly equal to the relativistic correction to the kinetic energy in first-order perturbation theory4,17. A comprehensive comparison between the energies calculated using Eq. (2), Eq. (5), and the available experimental data corresponding to the Hydrogen’s spectrum, was recently reported11,17. In that work, Eq. (25) was not used but the following approximate equation11:

Equation (29) was obtained assuming that the quasi-relativistic corrections included in ρo and ρ1 do not need to be accounting for because they are too small; therefore, Eq. (29) only includes the effect of the quasi-relativistic correction included in the centrifugal term in Eq. (17)11.

A comparison of Ęn,l dependence on Z, when Ęn,l is calculated using Eqs. (25), and (27–29), is shown in Fig. 3. In all cases the Schrödinger equation (Eqs. 4 and 28, gray continuous curves in Fig. 3) gives the smaller value of |Ęn,l|, while Eq. (29) gives the largest (gray dashed curves). As expected, all equations give similar values when |Ęn,l|/μc2 < < 1. Interestingly, at quasi-relativistic energies Eq. (27), the well-known equation given the relativistic correction to the kinetic energy in first-order perturbation theory (black dashed curves) underestimate the exact value of |Ęn,l| (Eq. 25), black continuous curves in Fig. 3. It is worth restating Eq. (25) is an exact result presented here for the first time, while Eq. (27) is a well-known approximated result4,17. This strongly supports the use of the Grave de Peralta equation (this is how the author proposes Eq. (5) to be called) for describing quantum particles with mass and spin-0 moving at quasi-relativistic energies10,11,12,13. A comparison between the energies calculated using Eq. (25), and the energy values calculated using the Dirac equation, allows a precise determination of which energy contributions are included in Eq. (25) and which ones are not included on it. The following equation gives the exact energies calculated using the Dirac equation2:

In Eq. (30), j = l ± ½2. Figure 4, shows a comparison of the energies calculated using Eqs. (25) and (30).

The Dirac’s energies include three corrections to the energies calculated using the Schrödinger equation2,17. The first is the relativistic correction to the kinetic energy. This correction is exactly included in Eq. (25)11,18. The second is the so-called Darwin correction, which is only non-zero when l = 02,11,17,18. The Darwin correction is related with the non-zero probability for the electron to be found in the nucleus when l = 02,17. The third correction is the spin–orbit correction, which is only non-zero when l > 02,11,17,18. As shown in Fig. 4a, the Darwin correction destabilizes the electron (Ęn,l,j > Ęn,l)17. This destabilization increases at quasi-relativistic energies (Z > > 1). As shown in Fig. 4b, the spin–orbit correction splits the quasi-relativistic energy level Ęn,l in two energy levels corresponding to j = l ± ½2,17. The spin–orbit correction also increases when Z > > 1. However, the energy difference |Ęn,l,j—Ęn,l| is smaller in Fig. 4b than in Fig. 4a because |Ę| is an order of magnitude larger in the ground state with n = 1 and l = 0 than in the excited state with n = 2 and l = 1.

Quasi-relativistic wave functions

The exact analytical wavefunctions of Eq. (5) are given by Eq. (8) with Ęn,l given by Eq. (25), Ωl,ml by Eq. (9), and χ(ζr) and τ(ζr) given by Eqs. (20–21) and (16). Therefore, the quasi-relativistic wavefunctions only differ from the wavefunctions of the Schrödinger equation in the values of Ę and in the radial part of the wavefunctions. τ(ρ) is given by Eq. (21) with jmax = n − (l + 1). Before using Eq. (22) for finding the coefficients, aj, ρ1 should be determined using Eqs. (14), (16), and (25), then ρo can be obtained using Eqs. (23) and (24). After τ(ρ) is found for given values of n and l, χ(ρ) can be obtained using Eq. (20). Finally, the complete unnormalized radial wavefunction is Яn,l = χ(ζr)/r. Therefore, the normalized radial wavefunctions are given by the following equation:

The above description constitutes a general method for obtaining any radial wavefunctions corresponding to Eq. (5). In what follows, for illustration purposes, the Яn,l(r) functions corresponding to the ground state and first excited states of Hydrogen-like atoms will be explicitly discussed. In addition, P(r) will be calculated using Eq. (1) for doing a meaningful comparison (Fig. 2) between Rn,l(r) and the corresponding radial wavefunctions of the Schrödinger equation4. Following the general method stated above, it was obtained the following expression for the ground state (n = 1, l = 0) of Hydrogen-like atoms:

In Eq. (32), A1,0, B1,0, and C1,0 are given by the following expressions:

In Eq. (33), Δ = Δ(l, Z) given by Eq. (24); therefore, by expressing the parameters A1,0, B1,0, and C1,0 as a series in powers of α each, and approximating them by the first terms of the series, one can obtain the following approximations for this parameters, which are valid when α2 Z2 < < 1:

Consequently, Я1,0(r) ~ Я1,0,Sch(r) when α2 Z2 < < 14:

In Eq. (35), rB = ℏ/(αμc) is the Bohr radius1,2,3,4,5. There are two possible values of l in the first excited state (n = 2); l = 0 and l = 11,2,3,4,5. For l = 0, it was obtained:

In Eq. (36):

Following the same procedure discussed above, it can be shown that Я2,0(r) ~ Я2,0,Sch(r)4:

Finally, it was obtained for n = 2 and l = 1:

In Eq. (39):

Here again, Я2,1(r) ~ Я2,1,Sch(r) when α2Z2 < < 14:

As shown in Fig. 3a,b, there is a notable difference between the energy Ę1,Sch ~—0.2663 μc2 corresponding to the ground state of the Hydrogen-like Fermium atom (Z = 100), which is calculated using the Schrödinger equation (Eqs. 4 and 28), and the energy Ę1,0 ~—0.7556 μc2 which is calculated using Eq. (25). At energies like Ę1,0 ~—0.7556 μc2, one should expect a notable difference between Я1,0(r) and Я1,0,Sch(r). This is confirmed by the probability functions (P(r/rB) shown in Fig. 5, which were calculated using Eqs. (1) and (31) and the functions Я1,0(r) and Я1,0,Sch(r) given by the Eqs. (32) and (35), respectively. Clearly, using the Schrödinger equation causes a notable underestimation of the confinement of the electron around the Fermium nucleus. This result was previously mentioned in the preliminary discussion of Fig. 2 made in the Introduction. The probability functions (P(r/rB) shown in Fig. 2 were calculated using Eqs. (1) and (31) and the functions Я2,1(r) and Я2,1,Sch(r) given by the Eqs. (39) and (41), respectively. Using Eq. (25) with n = 2, l = 1, and Z = 100, one can find that Ę2,1 ~ − 0.0724 μc2; therefore |Ę1,0| is an order of magnitude larger than |Ę2,1|. A comparison of Figs. 2 and 5 reveals that the underestimation of the electron confinement around the Fermium nucleus, which results from the use of the Schrödinger equation, dramatically increases as |Ęn,1| increases. This strongly supports the substitution, in ab-initio software packages, of the Schrödinger’s radial wavefunctions for the ones which are solutions of Eq. (5), when simulations involving the inner electrons of heavy atoms should be conducted.

Conclusions

In this work, first, it was obtained an exact analytical expression, which allows obtaining the quasi-relativistic energies of the bound states of the electron in Hydrogen-like atoms. The energies calculated in this way include the first-order perturbation relativistic correction to the kinetic energies calculated using the Schrödinger equation. Moreover, it was shown that Eq. (25) is the exact expression corresponding to the well-known approximate results given by Eq. (27). Second, it was discussed how to obtain the exact analytical wavefunctions of the quasi-relativistic wave equation used in this work (Eq. 5). The solutions were found following the same procedures, and with no more difficulty, than the ones present when solving the same problems using the Schrödinger equation. Nevertheless, the solutions found in this work are also valid when the particle is moving at energies as high as the energy associated to the particle’s mass. These quasi-relativistic atomic orbitals may be used for improving ab-initio software packages dedicated to numerical simulations in physical-chemistry and atomic and solid-state physics.

References

Bohm, D. Quantum Theory 11th edn. (Prentice-Hall, USA, 1964).

Davydov, A. S. Quantum Mechanics (Pergamon Press, USA, 1965).

Merzbacher, E. Quantum Mechanics 2nd edn. (Wiley, New York, 1970).

Griffiths, D. J. Introduction to Quantum Mechanics (Prentice Hall, USA, 1995).

Levine, I. N. Quantum Chemistry 7th edn. (Pearson Education, New York, 2014).

Slater, J. C. The self-consistent field and the structure of atoms. Phys. Rev. 32, 339–348 (1928).

Fischer, C. F. General Hartree–Fock program. Comput. Phys. Commun. 43, 355–365 (1987).

Parr, R. G. On the genesis of a theory. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 37, 327–347 (1990).

Home, D. Conceptual Foundations of Quantum Physics: An Overview from Modern Perspectives (Plenum Press, New York, 1997).

Grave de Peralta, L. Natural extension of the Schrödinger equation to quasi-relativistic speeds. J. Mod. Phys. 11, 196–213 (2020).

Grave de Peralta, L. Quasi-relativistic description of Hydrogen-like atoms. J. Mod. Phys. 11, 788–802 (2020).

Grave de Peralta, L. Quasi-relativistic description of a quantum particle moving through one-dimensional piecewise constant potentials. Results Phys. 11, 788 (2020).

Grave de Peralta, L. Did Schrödinger have other options?. Eur. J. Phys. https://doi.org/10.1088/1361-6404/aba7dc (2020).

Jackson, J. D. Classical Electrodynamics 2nd edn. (Wiley, New York, 1975).

Strange, P. Relativistic Quantum Mechanics: With Applications in Condensed Matter and Atomic Physics (Cambridge University Press, New York, 1998).

Greiner, W. Relativistic Quantum Mechanics: Wave Equations (Springer, New York, 1990).

Nanni, L. The hydrogen atom: A review on the birth of modern quantum mechanics. arXiv:1501.05894 (2015).

Grave de Peralta, L. A notable quasi-relativistic wave equation and its relation to the Schrödinger, Klein-Gordon, and Dirac equations. Can. J. Phys. (2020) (under review).

Van Lenthe, E., Baerends, E. J. & Snijders, J. G. Solving the Dirac equation, using the large component only, in a Dirac-type Slater orbital basis set. Chem. Phys. Lett. 236, 235–241 (1995).

Barysz, M. & Sadlej, A. J. Infinite-order two-component theory for relativistic quantum chemistry. J. Chem. Phys. 116, 2696 (2002).

Iliaš, M. & Saue, T. An infinite-order two-component relativistic Hamiltonian by a simple one-step transformation. J. Chem. Phys. 126, 064102 (2007).

Liu, W. & Peng, D. Exact two-component Hamiltonians revisited. J. Chem. Phys. 131, 031104 (2009).

Saue, T. et al. The DIRAC code for relativistic molecular calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 152, 204104 (2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The author did everything in the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Grave de Peralta, L. Exact quasi-relativistic wavefunctions of Hydrogen-like atoms. Sci Rep 10, 14925 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-71505-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-71505-w

This article is cited by

-

Specific relativistic uncertainty in light transmission with angular orientation non-zero

Applied Physics B (2023)

-

A Non-relativistic Approach to Relativistic Quantum Mechanics: The Case of the Harmonic Oscillator

Foundations of Physics (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.