Abstract

Due to the expanding use of non-invasive ventilation (NIV) in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), the question of enteral nutrition is increasingly raised in NIV users ALS patients. Here, we aimed to determine the prognostic factors for survival after gastrostomy placement in routine NIV users, taking into consideration ventilator dependence. Ninety-two routine NIV users ALS patients, who underwent gastrostomy insertion for severe dysphagia and/or weight loss, were included. We used a Cox proportional hazards model to identify factors affecting survival and compared time from gastrostomy to death and 30-day mortality rate between dependent (daily use ≥ 16 h) and non-dependent NIV users. The hazard of death after gastrostomy was significantly affected by 3 factors: age at onset (HR 1.047, p = 0.006), body mass index < 20 kg/m2 at the time of gastrostomy placement (HR 2.012, p = 0.016) and recurrent accumulation of airway secretions (HR 2.614, p = 0.001). Mean time from gastrostomy to death was significantly shorter in the dependent than in the non-dependent NIV users group (133 vs. 250 days, p = 0.04). The 30-day mortality rate was significantly higher in dependent NIV users (21.4% vs. 2.8%, p = 0.03). Pre-operative ventilator dependence and airway secretion accumulation are associated with worse prognosis and should be key decision-making criteria when considering gastrostomy tube placement in NIV users ALS patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Malnutrition and weight loss are independent negative prognostic factors for survival in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS)1. In case of severe dysphagia and/or malnutrition, gastrostomy placement (GP) is frequently offered to maintain adequate nutritional intake in these patients. Optimal timing for GP remains ill-defined and current guidelines1,2 recommend to take into account the severity of dysphagia, malnutrition, respiratory function (vital capacity, VC > 50%) and the patient’s general condition. Early insertion of a feeding tube is recommended2 but GP is at times delayed because of patient’s reservations about enteral nutrition. A recent large prospective study3 identified two main prognostic factors after GP: age at onset of ALS and nutritional status (evaluated by the percentage of weight loss from diagnosis to gastrostomy). In this study, 25% of the patients were routine users of non-invasive ventilation (NIV) but specific prognostic factors in this subpopulation were not studied. However, due to the increasing use of NIV in the ALS population, the question of GP in routine NIV users with ventilator dependence often arises in clinical practice. Here, we aimed to determine the prognostic factors after GP in routine NIV users, taking into account NIV use daily duration and the amount of airway secretions evaluated by the number of clearance treatment sessions required per day.

Patients and methods

Patients and data collection

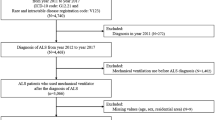

Between January 2014 and December 2017, 92 patients with a diagnosis of definite, probable, laboratory supported or possible ALS (according to the revised El Escorial criteria4) and who were routine NIV users, underwent GP at the Paris ALS center, France (Fig. 1). The indications for GP were a reduction of 5% or more of pre-onset weight, and/or severe dysphagia. The method of insertion—percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) or radiologically-inserted gastrostomy (RIG)—was decided by the referent neurologist5. RIG procedure was preferred for patients with a more compromised respiratory function whereas PEG procedure was usually chosen for patients at a less advanced stage of the disease, who were predicted to be able to tolerate endoscopy (able to flat, receive sedation)6. Whichever method of gastrostomy insertion was chosen, the NIV settings were systematically checked and optimized if necessary within 48 h before GP. The effectiveness of NIV was assessed with arterial blood gases, analysis of ventilator-recorded tracings and nocturnal oximetry. In patients with regular NIV use ≥ 16 h/day, GP was performed under NIV. For patients with nocturnal ventilation or up to 16 h per day, NIV was used if respiratory discomfort and/or oxygen desaturation occurred during the procedure. Oxygen supplementation into the ventilator was not routinely necessary. For RIG, premedication (with sedatives or narcotics) was not required but local anesthesia (lidocaine) was performed to prevent pain. Emergency airway equipment and an anesthesiologist were immediately available if needed. Patients were followed up every three months after GP. The following data were retrospectively collected from patients’ medical records: gender, age at onset, site of onset, method of GP, revised ALS Functional Rating Scale (ALSFRS-R) score, date of death or start of invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV), body mass index (BMI) at the time of GP, daily duration of NIV (< or ≥ 16 h/day), and amount of airway secretions. We estimated the amount of airway secretions by the number of airway clearance sessions (with mechanical insufflator-exsufflator) required per day during the hospitalization for the GP (“absent” or “occasional” when less than 1 session per day was needed, “recurrent accumulation” when at least 1 session per day was needed). Patients were admitted to the hospital a few days before gastrostomy placement, allowing quantification of airway secretions before gastrostomy insertion. Cough efficacy was systematically evaluated on hospital admission, and a cough assist device was available for all patients. Audible airway sounds with breathing (generated by secretions), with or without decreased oxygen saturation level and/or dyspnea, were the main criteria used to indicate the need for an airway clearance session.

Flowchart of patients included in the study. aThe indications for GP were a reduction of 5% or more of pre-onset weight, and/or severe dysphagia. The method of insertion was decided by the referent neurologist, RIG procedure being preferred for patients with a more compromised respiratory function. bThe NIV settings were systematically optimized if necessary within 48 h before GP. In patients with regular NIV use ≥ 16 h/day, GP was performed under NIV. For patients with nocturnal ventilation or up to 16 h per day, NIV was used if respiratory discomfort and/or oxygen desaturation occurred during the procedure. ALS: amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, GP: Gastrostomy placement, NIV: non-invasive ventilation, RIG: radiologically-inserted gastrostomy, PEG: percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy.

The cutoff time for follow-up was Oct 31, 2018. Five patients with disease duration > 10 years and two dead patients in whom the exact date of death was unknown were excluded from analysis. This retrospective study was performed in agreement with local ethical regulations and approved by the French National Data Protection Authority (registration number 2201855). It was performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations and informed consent was obtained for GP in all patients.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism 6 and Microsoft®Excel XLSTAT 2018.5. Mann–Whitney test was used for quantitative variables and Fischer’s test for qualitative variables. Survival was assessed using Kaplan–Meier curve. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to examine factors affecting survival after GP. As covariates, we included previously reported factors (age at disease onset3,7,8 and site of onset9) and BMI at the time of GP (< or ≥ 20 kg/m2) as a marker of nutritional status. Based on clinical judgment, we also included daily duration of NIV and amount of airway secretions. The level of significance was set at 0.05.

Results

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. There were no differences between dependent NIV users (≥ 16 h/day) and non-dependent patients (nocturnal ventilation or less than 16 h/day) in terms of age and site of disease onset, disease duration at the time of the procedure, method of GP, BMI and amount of airway secretions (Table 1). Overall median survival was 231 days. At the end of follow-up, 73 patients (87%) had died and one patient (in the non-dependent NIV user group) had started IMV 81 days after GP. The overall 30-day mortality rate was 5.9% (5 patients). Cox regression analysis showed that the hazard of death after gastrostomy in routine NIV users was significantly affected by 3 factors (Table 2): age at onset (HR 1.047 [95%CI 1.013–1.083]; p = 0.006), BMI measured at the time of GP (lower vs higher than 20 kg/m2, HR 2.012 [95%CI 1.141–3.545]; p = 0.016) and recurrent accumulation of airway secretions (HR 2.614 [95%CI 1.481–4.613]; p = 0.001). There was a trend towards a 1.8 increased risk of death in dependent NIV user patients, which did not reach statistical significance. To further investigate this aspect, we analyzed the time from gastrostomy to death or IMV (TTD). The mean TTD after gastrostomy was significantly shorter in the dependent than in the non-dependent NIV users group (133 days [range 2–348] vs. 250 days [range 18–1024], p = 0.04). Finally, the 30-day mortality rate was significantly higher in dependent NIV users than in non-dependent patients (respectively 3/14 [21.4%] and 2/71 [2.8%] patients, p = 0.03).

Discussion

In accordance with previous studies, we found that the hazard of death after GP in routine NIV users ALS patients was significantly affected by the age at onset and nutritional status3,8. In addition, we showed that, in this particular ALS patient population, preoperative respiratory status strongly influences prognosis. Indeed, recurrent accumulation of airway secretions (requiring at least one airway clearance session per day) was associated with a 2.6 increased risk of death after GP. Airway secretion accumulation is known to be associated with poor tolerance of NIV in ALS patients10. Our study shows that recurrent accumulation of airway secretions significantly worsens prognosis after GP in routine NIV users ALS patients, highlighting that adequate peri-operative management of airway secretions is crucial in this context.

Pre-operative NIV dependence (defined by NIV daily use ≥ 16 h/day) was also associated with a worst prognosis after GP, with a significantly higher 30-day mortality rate and lower TTD. Although the hazard of death tended to increase with NIV dependence, it did not reach statistical significance in the Cox regression analysis. This may be due to the high cut-off value for NIV use duration that we used to define “ventilation dependence”. There is no clear definition of a ventilator-dependent patient11. The cut-off of 16 h/day corresponds to the “life support ventilation” category defined by the French National Authority for Health, in which an external battery pack and a back-up ventilator must be provided to the patient12. However, patients unable to remain 12 h/day in spontaneous ventilation may already be considered as ventilator-dependent13. The threshold above which NIV dependence is associated with an increased risk of death after GP may thus be lower than 16 h/day. If NIV use per se does not seem to have an effect on survival after GP7,8,14, there are almost no data about the impact of daily NIV use duration on prognosis. One study found no significant difference in survival between patients under “continuous” NIV (i.e. who could not be weaned from ventilator) when compared to patients using it intermittently15. However, NIV use daily duration in the non-permanent users was not specified even though “intermittent” use encompasses very different clinical situations. Overall, our results highlight that GP should be discussed early enough in NIV users ALS patients, when ventilator daily use duration increases with a need for significant diurnal ventilation.

Our study has limitations. First, data were collected retrospectively and in a single center. In the context of impaired respiratory function, RIG insertion was chosen for most (93%) of the patients, which did not allow us to compare the effect on survival of the different insertion methods. The retrospective nature of the study also did not allow us to collect more precisely the NIV daily use duration for each patient, but only to classify patients as non ventilator-dependent or ventilator-dependent (i.e. daily use ≥ 16 h). We evaluated the amount of airway secretions by the number of clearance treatment sessions required per day—a parameter likely to be available in routine practice for most patients—but the exact volume of mucus expelled was not precisely quantified. Finally, our study did not evaluate the effect of gastrostomy on quality of life. However, the potential impact of GP on quality of life is an important parameter to consider, in the context of increasing ventilation dependence and motor disability.

Keeping those limitations in mind, the results of our study point out that pre-operative ventilator dependence and recurrent accumulation of airway secretions are key prognosis factors after GP in routine NIV user ALS patients. In addition to well-known prognosis factors (age and nutritional status), these two respiratory parameters should be evaluated when considering GP in NIV users ALS patients.

Conclusion

Pre-operative ventilator dependence and airway secretion accumulation are associated with worse outcome after gastrostomy insertion in NIV users ALS patients and should be taken into consideration in the decision-making process.

Data availability

The data supporting this study will be made available upon reasonable request.

References

Miller, R. G. et al. Practice parameter update: The care of the patient with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Multidisciplinary care, symptom management, and cognitive/behavioral impairment (an evidence-based review): Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 73, 1227–1233 (2009).

Andersen, P. M. et al. EFNS guidelines on the Clinical Management of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (MALS)—Revised report of an EFNS task force. Eur. J. Neurol. 19, 360–375 (2012).

ProGas Study Group. Gastrostomy in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ProGas): A prospective cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 14, 702–709 (2015).

Brooks, B. R. El Escorial World Federation of Neurology criteria for the diagnosis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Subcommittee on Motor Neuron Diseases/Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis of the World Federation of Neurology Research Group on Neuromuscular Diseases and the El Escorial ‘Clinical limits of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis’ workshop contributors. J. Neurol. Sci. 124(Suppl), 96–107 (1994).

Banfi, P. et al. Use of noninvasive ventilation during feeding tube placement. Respir. Care 62, 1474–1484 (2017).

Desport, J.-C. et al. Complications and survival following radiologically and endoscopically-guided gastrostomy in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. 6, 88–93 (2005).

Pena, M. J. et al. What is the relevance of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy on the survival of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis?. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. 13, 550–554 (2012).

Fasano, A. et al. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy, body weight loss and survival in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: A population-based registry study. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. Front. Degener. 18, 233–242 (2017).

Bokuda, K. et al. Predictive factors for prognosis following unsedated percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy in ALS patients: Post-PEG Prognosis in ALS. Muscle Nerve 54, 277–283 (2016).

Vandenberghe, N. et al. Absence of airway secretion accumulation predicts tolerance of noninvasive ventilation in subjects with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Respir. Care 58, 1424–1432 (2013).

Morelot-Panzini, C., Bruneteau, G. & Gonzalez-Bermejo, J. NIV in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: The ‘when’ and ‘how’ of the matter. Respirol. Carlton Vic https://doi.org/10.1111/resp.13525 (2019).

French National Authority for Health. Comment bien prescrire une ventilation mécanique (How to properly prescribe mechanical ventilation)? https://www.has-sante.fr/upload/docs/application/pdf/2013-04/comment_bien_prescrire_une_ventilation_mecanique_fiche_buts.pdf (2013).

Rafiq, M. K., Proctor, A. R., McDermott, C. J. & Shaw, P. J. Respiratory management of motor neurone disease: A review of current practice and new developments. Pract. Neurol. 12, 166–176 (2012).

McDermott, C. J. & Stavroulakis, T. Gastrostomy in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: Effects of non-invasive ventilation-Authors’ reply. Lancet Neurol. 14, 1153 (2015).

Park, J. H. & Kang, S.-W. Percutaneous radiologic gastrostomy in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis on noninvasive ventilation. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 90, 1026–1029 (2009).

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all the patients included in the study for agreeing to the use of their clinical and paraclinical data for research and educational purposes.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study concept and design: AH, GB. Data acquisition: all authors. Data analysis: AH, GB. Drafting of the manuscript: AH, CM and GB. All authors critically reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hesters, A., Amador, M.d., Debs, R. et al. Predictive factors for prognosis after gastrostomy placement in routine non-invasive ventilation users ALS patients. Sci Rep 10, 15117 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-70422-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-70422-2

This article is cited by

-

Nutritional and metabolic factors in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

Nature Reviews Neurology (2023)

-

Multidisciplinary care in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis

Neurological Sciences (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.