Abstract

Similar to humans, the fecal microbiome of dogs may be useful in diagnosing diseases or assessing dietary interventions. The accuracy and reproducibility of microbiome data depend on sample integrity, which can be affected by storage methods. Here, we evaluated the ability of a stabilization device to preserve canine fecal samples under various storage conditions simulating shipping in hot or cold climates. Microbiota data from unstabilized samples stored at room temperature (RT) and samples placed in PERFORMAbiome·GUT collection devices (PB-200) (DNA Genotek, Inc. Ottawa, Canada) and stored at RT, 37 °C, 50 °C, or undergoing repeated freeze–thaw cycles, were compared with freshly extracted samples. Alpha- and beta diversity indices were not affected in stabilized samples, regardless of storage temperature. Unstabilized samples stored at RT, however, had higher alpha diversity. Moreover, the relative abundance of dominant bacterial phyla (Firmicutes, Fusobacteria, Bacteriodetes, and Actinobacteria) and 24 genera were altered in unstabilized samples stored at RT, while microbiota abundance was not significantly changed in stabilized samples stored at RT. Our results suggest that storage method is important in microbiota studies and that the stabilization device may be useful in maintaining microbial profile integrity, especially for samples collected off-site and/or those undergoing temperature changes during shipment or storage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The canine gastrointestinal (GI) tract harbors a highly dense and diverse population of microorganisms, including bacteria, fungi, archaea, and viruses, collectively termed microbiota. In recent years, DNA-based, high-throughput technologies have allowed a better characterization of the GI microbiome and its role in host health and disease. A large number of studies have demonstrated that altered gut microbiota composition and functions are associated with several metabolic disorders, such as obesity1,2, diabetes3,4, inflammatory bowel diseases5,6,7, autoimmune diseases8,9 and cancers10,11 in humans and/or dogs. Because microbial shifts are often noted with disease, microbiome profiles may be used as biomarkers for diagnosis and/or monitoring in the future12,13,14.

The microbiome field has much to offer, but appropriate sample collection and storage methods are needed for sample integrity and accurate and reproducible data. It has been shown that microbiome profiles of human fecal samples are changed after 48 hours of storage at ambient temperatures15,16. Many studies also demonstrated that proper stabilization and storage methods are key to having accurate and reproducible microbiome data15,17,18,19,20,21. To date, the most appropriate and widely used collection protocol is to rapidly freeze and store samples at − 80° or − 20 °C17,21,22. However, these methods may not be practical in many cases. For example, very low-temperature storage might not always be accessible when collecting fecal samples from study subjects at home or in remote locations. Although studies have reported that storing samples at 4 °C slows bacterial growth and maintains sample integrity, they must be processed or stored at lower temperatures within 24 hours21,23. In addition, maintaining samples at low temperatures during shipment may be challenging and costly. Therefore, development of strategies able to stabilize samples at ambient temperature is of great interest.

Previous studies used a commercially available ambient temperature stabilization device OMNIgene•GUT (DNA Genotek, Inc. Ottawa, Canada) to collect and store human fecal samples. Results suggested that this device maintained the integrity of microbiome data and allowed for a higher recovery of nucleic acids at room temperature when compared with freezing at − 20 °C23,24,25. Similar to humans, researchers are interested in identifying the relationship between the GI microbiota, nutritional status, and health of dogs. The number of studies of the dog microbiome has grown in recent years26,27,28. There is, however, limited information about canine fecal sample collection and storage methods.

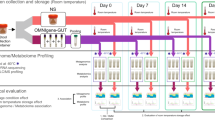

The microbiota communities of humans and dogs are distinct. The human gut is dominated by Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes29,30 while the canine gut is co-dominated by Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes and Fusobacterium6,31. Here, we used a similar commercial stabilization device designed specifically for animals, PERFORMAbiome•GUT (DNA Genotek, Inc. Ottawa, Canada), to study canine fecal sample collection and storage. In addition to what was conducted in previous human studies23,24,25, the current study investigated the effectiveness of this device in preserving samples during different storage temperatures that was meant to mimic shipment conditions where temperatures often change. The effects of a longer storage time (60 days in this study; up to 28 days in human studies) at room temperature (RT) were also studied. To assess the ability of this device to preserve fecal samples in different conditions, stabilized samples were stored at (1) RT (~ 23 °C), (2) 37 °C, (3) 50 °C, or (4) underwent repeated freeze–thaw (-20 °C/30 °C) cycles. We compared samples extracted on the collection day (baseline) to stabilized samples incubated for 1, 3, 14 or 60 days. Unstabilized samples were also collected and stored at RT to compare with stabilized samples stored at RT (Fig. 1). Finally, in order to determine intra-sampling variation, we compared samples collected from three locations of each fecal sample.

Experimental design. Fresh fecal samples were collected from 30 healthy beagles. Each sample was aliquoted into three stabilization devices and one unstabilized aliquot, and incubated under different conditions. One stabilized sample was aliquoted and incubated at 37 °C and 50 °C after baseline microbiota data were obtained. Microbiota data were obtained at different time points as marked.

Results

Microbiome profiles are largely unaffected by storage method at baseline

All baseline samples were extracted on the collection day within 2 hours, including three stabilized samples (D0-37/50, D0-FT, D0-RT) and one unstabilized sample (D0-UNST) were compared. The stabilized samples were from one defecation and were not handled differently. An even sampling depth of 22,931 sequences per sample was used for assessing alpha- and beta diversity measures. Alpha- (p = 0.506) and beta diversity measures were not different between baseline samples on the collection day (D0) (Fig. 2). Relative abundances of bacteria at the phylum level were not different (p > 0.05) between samples. At the genus level, the relative abundances of Faecalibacterium (p = 0.001; stabilized: 1.10%; UNST: 0.57%) and Phascolarctobacterium (p < 0.001; stabilized: 2.74%; UNST: 1.14%) were greater, while relative abundances of Lactobacillus (p = 0.047; stabilized: 1.70%; UNST: 3.31%) and Clostridium (p = 0.004; stabilized: 0.77%; UNST: 1.17%) were lower in stabilized samples (D0-37/50, D0-FT, D0-RT) compared with unstabilized samples (D0-UNST). No other differences to taxa were observed.

Fecal microbiota communities of baseline stabilized samples (D0-37/50, D0-FT, D0-RT) and unstabilized sample (D0-UNST). (A) Alpha diversity measures, including phylogenetic diversity (PD) whole tree (shown), suggested that species richness and diversity were not affected by collection method at baseline (ANOVA, p = 0.506). Principal coordinates analysis plots of unweighted (B) and weighted (C) UniFrac distances of fecal microbial communities revealed that beta diversity was not altered by collection method at baseline.

Stabilized samples stored at high temperatures yield consistent microbiota profiles that are similar to baseline samples

To validate the ability of the stabilization device to preserve samples at high temperatures, which could occur during shipment, stabilized samples were stored at 37 °C or 50 °C for 1 day or 3 days (D1-37, D3-37, D1-50, D3-50, respectively) and compared to baseline samples (D0-37/50). An even sampling depth of 6,310 sequences per sample was used for evaluating alpha- and beta diversity measures. Alpha- (p = 0.944) and beta diversity measures were not affected by temperature or storage time (Fig. 3A–E). At the phylum level, the relative abundance of Firmicutes was greater (p = 0.026) in samples at baseline (24.80%) than in D1-37 (18.73%) and D1-50 (18.70%) samples. At the genus level, the relative abundance of Ruminococcus was greater (p = 0.004) in baseline samples (0.09%) than in D1-37 (0.04%), D3-37 (0.05%), D1-50 (0.05%), and D3-50 (0.05%) samples. No other differences to taxa were observed. Changes of relative abundance of genera were small as correlation coefficients between baseline and D1-37 (r = 0.972), D3-37 (r = 0.967), D1-50 (r = 0.981), and D3-50 (r = 0.976) were high (Fig. 3F–I).

Fecal microbiota communities of stabilized samples at baseline (D0-37/50) and stored at 37 °C and 57 °C for 1 (D1-37, D1-50) and 3 days (D3-37, D3-50). (A) Alpha diversity measures, including phylogenetic diversity (PD) whole tree (shown), suggested that species richness and diversity were not affected by storage condition (ANOVA, p = 0.944). Principal coordinates analysis plots of unweighted (B) and weighted (C) UniFrac distances of fecal microbial communities as well as unweighted (D) and weighted (E) UniFrac distances from baseline revealed that beta diversity was not altered by storage condition. Scatterplots show the relative abundance of each genus in baseline samples against samples stored at 37 °C for 1 (F) and 3 days (G), and samples stored at 50 °C for 1 (H) and 3 days (I).

Microbiota profile of stabilized samples is largely unaffected by freeze–thaw cycles

Stabilized samples that underwent 6 freeze–thaw cycles (D14-FT) were compared with baseline samples (D0-RT) to evaluate the effectiveness of the device to stabilize samples undergoing temperature changes. An even sampling depth of 28,957 sequences per sample was used for assessing alpha- and beta diversity measures. Alpha- (p = 0.630) and beta diversity measures were not different between samples before and after the freeze–thaw cycles (Fig. 4A–C). Relative abundances of bacteria at the phylum level were not affected (p > 0.05) by freeze–thaw cycles. At the genus level, relative abundances of Collinsella were greater (p = 0.041; D0: 0.37%, D14: 0.68%), while relative abundances of Faecalibacterium (p = 0.010; D0: 1.13%; D14: 0.67%) and Phascolarctobacterium (p = 0.008; D0: 2.70%; D14: 1.83%) were lower in samples stored at freeze–thaw cycles for 14 days (D14-FT). No other differences to taxa were observed. Changes of relative abundance of genera were small as the correlation coefficient between baseline and D14-FT was high (r = 0.984; Fig. 4D).

Fecal microbiota communities of stabilized samples at baseline (D0-FT) and stored at freeze–thaw cycles (D14-FT). (A) Alpha diversity measures, including phylogenetic diversity (PD) whole tree (shown), suggested that species richness and diversity were not affected by storage condition (ANOVA, p = 0.630). Principal coordinates analysis plots of unweighted (B) and weighted (C) UniFrac distances of fecal microbial communities revealed that beta diversity was not altered by storage condition. The scatterplot (D) shows the relative abundance of each genus in baseline samples against samples after freeze–thaw cycles.

Stabilized samples yield consistent microbiota profiles, while unstabilized samples result in substantial changes in microbiota profiles when stored at room temperature

To investigate the ability of the device to stabilize fecal samples at ambient temperature, stabilized samples stored at RT for 14 (D14-RT) and 60 days (D60-RT) were compared with baseline samples (D0-RT) as well as unstabilized samples from baseline (D0-UNST) and those stored at RT for 14 days (D14-UNST). An even sampling depth of 22,875 sequences per sample was used for evaluating alpha- and beta diversity measures. Alpha-diversity measures (Fig. 5A), including phylogenic diversity whole tree (p < 0.001), Chao1 (p < 0.001) and observed OTU (operational taxonomic unit; p < 0.001) revealed higher species richness in unstabilized samples stored at room temperature for 14 days (D14-UNST) than in stabilized samples or baseline unstabilized samples. In addition, the Chao1 metric showed a lower diversity in D60-RT than those of D0-RT (p = 0.0193), D14-RT (p = 0.0431), and D0-UNST (p = 0.013; Fig. 5A). Beta diversity measures revealed a shift for unstabilized samples (Fig. 5B,C). Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) plot of weighted UniFrac distance showed that D14-UNST samples clustered together and away from other samples (Fig. 5C). In addition, D14-UNST and D60-RT had a greater unweighted UniFrac distance from baseline than D14-RT (p < 0.001; Fig. 5D) and D14-UNST had a greater weighted UniFrac distance from baseline than stabilized samples (p < 0.001; Fig. 5E). Relative abundances of four dominant phyla were different between D14-UNST samples and stabilized samples: Actinobacteria (p < 0.001) and Firmicutes (p < 0.001) were greater, while Bacteroidetes (p < 0.001) and Fusobacteria were lower (p < 0.001) in D14-UNST samples than D0-UNST and stabilized samples (Table 1). Additionally, relative abundances of many dominant genera were different between D14-UNST samples and stabilized samples (Table 1). Changes of relative abundance of genera in stabilized samples after 14 days and 60 days at RT were small because the correlation coefficients between D0-RT and D14-RT (r = 0.975) and D60-RT (r = 0.961) were high (Fig. 5F,G). A great change was observed in unstabilized samples, where the correlation coefficient between D0-UNST and D14-UNST was r = 0.443 (Fig. 5H).

Fecal microbiota communities of stabilized and unstabilized samples at baseline (D0-RT, D0-UNST) and stored at room temperature (RT) for 14 (D14-RT, D14-UNST) and 60 days (D60-RT). (A) Alpha diversity measures, including phylogenetic diversity (PD) whole tree, Chao1, and observed operational taxonomic units (OTUs), suggested that species richness and diversity were greater in unstabilized samples stored at RT for 14 days (Tukey’s HSD, p < 0.001). The Chao1 metric showed a lower diversity in D60-RT than those of D0-RT (Tukey’s HSD, p = 0.0193), D14-RT (Tukey’s HSD, p = 0.0431), and D0-UNST (Tukey’s HSD, p = 0.013). Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) plots of unweighted (B) UniFrac distances of fecal microbial communities revealed that beta diversity was not altered by storage condition. PCoA plots of weighted (C) UniFrac distance showed that D14-UNST samples clustered together (circled area) and away from other samples. Unweighted UniFrac distance from baseline (D) revealed that D14-UNST and D60-RT had greater distance than 14-RT. Weighted UniFrac distance (E) showed that D14-UNST had a greater distance than stabilized samples. a,b mean values with unlike letters were significantly different (Tukey’s HSD, p < 0.05). Scatterplots show the relative abundance of each genus in baseline samples against stabilized samples stored at RT for 14 (F) and 60 days (G), and unstabilized samples stored at RT for 14 days (H).

Microbial composition varies among collection sites within a fecal sample

To evaluate the intra-sampling variation, we compared aliquots collected from both ends (Rep1, 3) and the middle (Rep2) of each fresh fecal sample. At the phylum level, relative abundance of Actinobacteria was different (p = 0.021) among collection sites. Relative abundances of several genera, including Clostridium (p = 0.016), Collinsella (p = 0.026), Dialister (p = 0.023), Escherichia (p = 0.045), Faecalibacterium (p = 0.011), Phascolarctobacterium (p = 0.001), Roseburia (p = 0.004), Ruminococcus (p < 0.001), Sarcina (p = 0.023), and Shigella (p = 0.019), were different among collection sites (Table 2).

Discussion

As the relationship between the gut microbiota and human health has become clearer, interest in the microbiome field has increased dramatically. A similar trend has been observed in companion animals, as pet owners are now considering their pets to be family members and prioritize health and longevity. One critical factor that contributes to microbiome data integrity and accuracy is sample collection and storage methods. Currently, rapid freezing and storage of fecal samples at − 80 °C is widely considered to be the gold standard. This method, however, is often challenging and costly, which limits the ability of collection at remote sites or collection of a large sample number. Therefore, an ambient collection and stabilization strategy would be of great value for such microbiome studies.

In this study, we collected and stored canine fecal samples using a commercially available device, PERFORMAbiome•GUT (DNA Genotek, Inc. Ottawa, Canada). Stabilized samples were incubated at different conditions to evaluate the ability of the stabilization device to preserve fecal samples for microbiota analysis. In accordance with previous studies using a similar device for humans23,24,32, our results revealed that alpha- (species richness and evenness within samples) and beta diversity (species richness among samples) were not altered in stabilized samples after storage at 37 °C and 50 °C for up to 3 days, at RT for up to 14 days, or undergoing 6 freeze–thaw cycles. In contrast, substantial changes were observed in the unstabilized samples, where alpha diversity increased, and the abundance of several taxa were altered after 14 days at RT. In support of our findings, shifted microbiota profiles were reported in unstabilized human samples after 48 or 72 hours at RT16,23,33.

For stabilized samples stored at RT for 60 days, the Chao1 index for alpha diversity measures was decreased compared with baseline samples and samples stored for 14 days. The Chao1 index is a metric highly favoring rare OTUs. The longer storage with the PERFORMAbiome•GUT kit may reduce the diversity by decreasing numbers of rare OTUs. However, the relative abundance of the main phyla and genera were not significantly different among stabilized samples stored at RT at any time points. Additionally, correlations of relative abundance of genera after 60 days against baseline were high (r = 0.961). This was also observed in a previous study where human and canine fecal samples were stored at RT for 56 days using the OMNIgene•GUT, and the correlations of OTU abundance against baseline samples were r = 0.9632.

Previous studies using OMNIgene•GUT kits for human fecal samples have reported changes in the relative abundance of a few genera. For example, a decreased abundance of Sutterella and Faecalibacterium were observed after 72 hours at RT23. Hill et al. noted the decreased abundance of Clostridium (XIVa and XVII) and Sorobacter as well as an increased abundance of Faecalibacterium after 1 week at RT34. Here, we found changes in Faecalibacterium and Clostridium, but not other genera reported in previous studies. After fecal samples were stabilized in the PERFORMAbiome•GUT device, an immediate increase in Faecalibacterium and decrease in Clostridium were noted when compared to the unstabilized samples. Additionally, the abundance of Faecalibacterium was decreased after six freeze–thaw cycles. This stabilization device and a similar product may not have the best ability to preserve Faecalibacterium as shown here and in two previous studies23,34. Therefore, this should be considered when testing samples of animals with gastrointestinal diseases, whereby Faecalibacterium abundance has been shown to be altered in both humans and dogs13,35,36.

Significant changes in the abundance of a few other taxa were observed in stabilized samples at high temperatures or freeze–thaw cycles. These changes, however, are considered relatively small when samples are stored at extreme conditions. In addition, correlations of genera abundance between baseline and after storage were high (r > 0.96). Similar to the results reported by Song et al. (2016) who used OMNIgene•GUT kits for human and dog fecal samples, small changes were noted in stabilized samples stored under two freeze–thaw (− 20 °C/RT) and two heat (4 °C/40 °C) cycles, as correlations between OTU abundance at baseline and after 8 weeks were high (r = 0.93 and 0.77, respectively). The unstabilized samples, on the other hand, showed large shifts after freeze–thaw or heat cycles (r = 0.15 and 0.41, respectively)32.

Finally, we showed the intra-sampling variation of the microbiota profile in this study. The relative abundance of nine genera were different among collection sites within a fecal sample. Gorzelak et al. also found high variation in microbial abundance when human fecal samples were not homogenized before DNA extraction37. Therefore, these data suggest that homogenization of fecal samples should be done so that a consistent microbial composition reflecting the entire fecal sample is reported.

Our findings demonstrate that the collection and storage strategy tested in this study minimized changes in microbiota profiles of canine fecal samples stored at ambient temperatures or undergoing significant temperature changes. This device should enable sample collection and storage when ultra-low temperature storage and transport methods are not feasible, allowing for collection at remote locations. This strategy also allows for shipment at low or high temperatures and long-term storage at ambient temperatures. Together, this device appears to be a robust approach for canine fecal sample collection and storage.

Methods

Fecal sample collection

All animal care and experimental procedures were approved by the University of Illinois Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee before experimentation (protocol #17008, #17135, and #17180). All methods were performed in accordance with the United States Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Fresh fecal samples were collected from 30 healthy female adult beagles (average age: 4.1 ± 1.3 years) within 15 minutes of defecation. All fecal samples were scored according to the following scale that has been used by our research group for decades38,39: 1 = hard, dry pellets, small hard mass; 2 = hard, well formed, dry stool; 3 = soft, formed, and moist stool, retains shape; 4 = soft, unformed stool, assumes shape of container; and 5 = watery, liquid that can be poured. All fecal samples had scores ranged from 2.5–3, which are considered to be normal, healthy stools. Three subsamples (2 ml; from each end and middle of a fecal sample) were collected and placed into cryovials and immediately frozen and stored at − 80 °C. The remaining fecal samples were aliquoted either into a conical tube stored at room temperature or into three PERFORMAbiome•GUT collection devices (PB-200) (DNA Genotek, Inc. Ottawa, Canada). After baseline microbiota data were obtained from each collection device, one stabilized sample was aliquoted and incubated at 37 °C and 50 °C. The other two stabilized samples were stored at RT (~ 23 °C) or undergoing six freeze–thaw (− 20 °C/30 °C) cycles (Fig. 1).

Fecal DNA extraction, amplification, and sequencing

Total bacterial DNA of all fecal samples was extracted according to the timeline shown in Fig. 1. Baseline samples were extracted on the collection day within 2 hours of collection. Total DNA was extracted according to manufacturer’s instructions using the MO BIO PowerFecal Kit (MO BIO Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA) with bead beating using a vortex adaptor. Concentration of extracted DNA was quantified using a Qubit® 3.0 Fluorometer (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). Following extraction, the V3-V4 region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene was amplified by polymerase chain reaction using the following forward and reverse primers: Bakt_341F (CCTACGGGNGGCWGCAG) and Bakt_805R (GACTACHVGGGTATCTAATCC), which include an additional 0–7 bases between the transposase and primer sequences, and paired such that the final combination of primer pairs sum to the same length. 16S rRNA template amplification and index addition was performed using Illumina’s recommended 16S library preparation protocol with a customized dual index version of Illumina’s Nextera XT indexing protocol. Amplicons were sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq using 2 × 300 bp PE MiSeq reagent kit V3. Base calling diversity for amplicon sequencing was increased through use of 10% PhiX spike into each sequencing pool and through variable length spacers in primer sequences.

Bioinformatics and statistical analysis

Trimmomatic was used to remove sequencing adaptors and low-quality reads40. The FLASH algorithm was used for read merging and automated rejection of low quality sequences41. Quality screening for length and ambiguous bases was performed with proprietary scripts. Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology (QIIME 1.9.1)42 was used to process the sequence data. A closed-reference taxonomic classification was performed, where each sequence was aligned to the curated SILVA version 123 reference database43. Sequences were aligned at 97% sequence identity using the NINJA-OPS algorithm, version 1.5.144. At 97% sequence identity, each OTU represents a genetically unique group of biological organisms. These OTUs were then assigned a curated taxonomic label based on the seven-level SILVA taxonomy. Alpha- and beta diversity measures were assessed at an even sampling depth sequences per sample. Data for each specific comparison (i.e., research aim) were analyzed separately. Alpha diversity was estimated using phylogenetic diversity whole tree, Chao1, and observed OTU matrices. Beta diversity was calculated using weighted and unweighted UniFrac45 distance measures, and presented as PCoA plots. UniFrac distances between baseline and samples stored at 37 °C and 50 °C as well as baseline and samples stored at RT were calculated and compared. Correlation of relative abundance of genera between baseline and samples after incubations were analyzed using Pearson’s correlation. Statistical analysis was conducted via Statistical Analyses of Metagenomic Profiles (STAMP) software 2.1.346 and SAS 9.4 using ANOVA and Tukey–Kramer multiple comparison tests. All tests were corrected for multiple inferences using the Benjamini–Hochberg method to control for false discovery rate47. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

References

Ley, R. E., Turnbaugh, P. J., Klein, S. & Gordon, J. I. Human gut microbes associated with obesity. Nature444, 1022–1023 (2006).

Turnbaugh, P. J. & Gordon, J. I. The core gut microbiome, energy balance and obesity. J. Physiol.587, 4153–4158 (2009).

Karlsson, F. H. et al. Gut metagenome in European women with normal, impaired and diabetic glucose control. Nature498, 99–103 (2013).

Hartstra, A. V., Bouter, K. E. C., Bäckhed, F. & Nieuwdorp, M. Insights into the role of the microbiome in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care38, 159–165 (2015).

Kostic, A. D., Xavier, R. J. & Gevers, D. The microbiome in inflammatory bowel disease: current status and the future ahead. Gastroenterology146, 1489–1499 (2014).

Suchodolski, J. S., Dowd, S. E., Wilke, V., Steiner, J. M. & Jergens, A. E. 16S rRNA gene pyrosequencing reveals bacterial dysbiosis in the duodenum of dogs with idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease. PLoS ONE7, e39333 (2012).

Xenoulis, P. G. et al. Molecular-phylogenetic characterization of microbial communities imbalances in the small intestine of dogs with inflammatory bowel disease. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol.66, 579–589 (2008).

Kim, D., Yoo, S.-A. & Kim, W.-U. Gut microbiota in autoimmunity: potential for clinical applications. Arch. Pharm. Res.39, 1565–1576 (2016).

Markle, J. G. M. et al. Sex differences in the gut microbiome drive hormone-dependent regulation of autoimmunity. Science339, 1084–1088 (2013).

Feng, Q. et al. Gut microbiome development along the colorectal adenoma–carcinoma sequence. Nat. Commun.6, 6528 (2015).

Schwabe, R. F. & Jobin, C. The microbiome and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer13, 800–812 (2013).

Daniels, L. et al. Fecal microbiome analysis as a diagnostic test for diverticulitis. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis.33, 1927–1936 (2014).

Suchodolski, J. S. Diagnosis and interpretation of intestinal dysbiosis in dogs and cats. Vet. J.215, 30–37 (2016).

Zitvogel, L., Ma, Y., Raoult, D., Kroemer, G. & Gajewski, T. F. The microbiome in cancer immunotherapy: diagnostic tools and therapeutic strategies. Science359, 1366–1370 (2018).

Carroll, I. M., Ringel-Kulka, T., Siddle, J. P., Klaenhammer, T. R. & Ringel, Y. Characterization of the fecal microbiota using high-throughput sequencing reveals a stable microbial community during storage. PLoS ONE7, e46953 (2012).

Roesch, L. F. W. et al. Influence of fecal sample storage on bacterial community diversity. Open Microbiol. J.3, 40–46 (2009).

Cardona, S. et al. Storage conditions of intestinal microbiota matter in metagenomic analysis. BMC Microbiol.12, 158 (2012).

Fouhy, F. et al. The effects of freezing on faecal microbiota as determined using MiSeq sequencing and culture-based investigations. PLoS ONE10, e0119355 (2015).

Guo, Y. et al. Effect of short-term room temperature storage on the microbial community in infant fecal samples. Sci. Rep.6, 26648 (2016).

Nechvatal, J. M. et al. Fecal collection, ambient preservation, and DNA extraction for PCR amplification of bacterial and human markers from human feces. J. Microbiol. Methods72, 124–132 (2008).

Tedjo, D. I. et al. The effect of sampling and storage on the fecal microbiota composition in healthy and diseased subjects. PLoS ONE10, e0126685 (2015).

Wu, G. D. et al. Sampling and pyrosequencing methods for characterizing bacterial communities in the human gut using 16S sequence tags. BMC Microbiol.10, 206 (2010).

Choo, J. M., Leong, L. E. & Rogers, G. B. Sample storage conditions significantly influence faecal microbiome profiles. Sci. Rep.5, 16350 (2015).

Anderson, E. L. et al. A robust ambient temperature collection and stabilization strategy: enabling worldwide functional studies of the human microbiome. Sci. Rep.6, 31731 (2016).

Panek, M. et al. Methodology challenges in studying human gut microbiota – effects of collection, storage, DNA extraction and next generation sequencing technologies. Sci. Rep.8, 5143 (2018).

Alessandri, G. et al. Metagenomic dissection of the canine gut microbiota: insights into taxonomic, metabolic and nutritional features. Environ. Microbiol.21, 1331–1343 (2019).

Deng, P. & Swanson, K. S. Gut microbiota of humans, dogs and cats: current knowledge and future opportunities and challenges. Br. J. Nutr.113, S6–S17 (2015).

Guard, B. C. et al. Characterization of the fecal microbiome during neonatal and early pediatric development in puppies. PLoS ONE12, e0175718 (2017).

Gill, S. R. et al. Metagenomic analysis of the human distal gut microbiome. Science312, 1355–1359 (2006).

Eckburg, P. B. et al. Microbiology: diversity of the human intestinal microbial flora. Science308, 1635–1638 (2005).

Middelbos, I. S. et al. Phylogenetic characterization of fecal microbial communities of dogs fed diets with or without supplemental dietary fiber using 454 pyrosequencing. PLoS ONE5, e9768 (2010).

Song, S. J. et al. Preservation methods differ in fecal microbiome stability, affecting suitability for field studies. mSystems1, e00021-e116 (2016).

Shaw, A. G. et al. Latitude in sample handling and storage for infant faecal microbiota studies: the elephant in the room? Microbiome4, 40 (2016).

Hill, C. J. et al. Effect of room temperature transport vials on DNA quality and phylogenetic composition of faecal microbiota of elderly adults and infants. Microbiome4, 19 (2016).

Lopez-Siles, M., Duncan, S. H., Garcia-Gil, L. J. & Martinez-Medina, M. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii: from microbiology to diagnostics and prognostics. ISME J.11, 841–852 (2017).

Sokol, H. et al. Low counts of Faecalibacterium prausnitzii in colitis microbiota. Inflamm. Bowel Dis.15, 1183–1189 (2009).

Gorzelak, M. A. et al. Methods for improving human gut microbiome data by reducing variability through sample processing and storage of stool. PLoS ONE10, e0134802 (2015).

Lin, C.-Y. et al. Effects of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae fermentation product on fecal characteristics, nutrient digestibility, fecal fermentative end-products, fecal microbial populations, immune function, and diet palatability in adult dogs. J. Anim. Sci.97, 1586–1599 (2019).

Swanson, K. S., Grieshop, C. M., Flickinger, E. A., Merchen, N. R. & Fahey, G. C. Effects of supplemental fructooligosaccharides and mannanoligosaccharides on colonic microbial populations, immune function and fecal odor components in the canine. J. Nutr.132, 1717S-1719S (2002).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics30, 2114–2120 (2014).

Magoč, T. & Salzberg, S. L. FLASH: fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics27, 2957–2963 (2011).

Caporaso, J. G. et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods7, 335–336 (2010).

Yilmaz, P. et al. The SILVA and “all-species living tree project (LTP)” taxonomic frameworks. Nucleic Acids Res.42, D643–D648 (2014).

Al-Ghalith, G. A., Montassier, E., Ward, H. N. & Knights, D. NINJA-OPS: fast accurate marker gene alignment using concatenated ribosomes. PLOS Comput. Biol.12, e1004658 (2016).

Lozupone, C. & Knight, R. UniFrac: a new phylogenetic method for comparing microbial communities. Appl. Environ. Microbiol.71, 8228–8235 (2005).

Parks, D. H., Tyson, G. W., Hugenholtz, P. & Beiko, R. G. STAMP: Statistical analysis of taxonomic and functional profiles. Bioinformatics30, 3123–3124 (2014).

Benjamini, Y. & Hochberg, Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J. R. Stat. Soc.57, 289–300 (1995).

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank Meredith Carroll for her assistance with fecal sample collections. This study was funded by DNA Genotek, Inc.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.S.S. designed the study. C.-Y.L. and E.D. performed laboratory analyses. T.-W.L.C. conducted bioinformatics and statistical analyses. C.-Y.L. performed sample collections and statistical analyses, and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

E.D. is employed by DNA Genotek, Inc. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lin, CY., Cross, TW.L., Doukhanine, E. et al. An ambient temperature collection and stabilization strategy for canine microbiota studies. Sci Rep 10, 13383 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-70232-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-70232-6

This article is cited by

-

The gut microbiota facilitate their host tolerance to extreme temperatures

BMC Microbiology (2024)

-

Validation of method for faecal sampling in cats and dogs for faecal microbiome analysis

BMC Veterinary Research (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.