Abstract

Organophosphorus compounds, such as chemical warfare nerve agents and pesticides, are known to cause neurological damage. This study measured nerve agent-related neuropathology and determined whether quantitative T2 MRI could be used as a biomarker of neurodegeneration. Quantitative T2 MRI was performed using a 9.4 T MRI on rats prior to and following soman exposure. T2 images were taken at least 24 h prior, 1 h and 18–24 h after soman exposure. Rats were pre- and post-treated with HI-6 dimethanesulfonate and atropine methyl nitrate. A multicomponent T2 acquisition and analysis was performed. Brains were stained with Fluoro-Jade C to assess neurodegeneration. Rats exposed to soman developed behavioral expression of electrographic seizures. At 18–24 h after soman exposure, significant increases in T2, a possible marker of edema, were found in multiple regions. The largest changes were in the piriform cortex (before: 47.7 ± 1.4 ms; 18–24 h: 82.3 ± 13.4 ms). Fluoro-Jade C staining showed significant neurodegeneration 18–24 h post exposure. The piriform cortex had the strongest correlation between the change in relaxation rate and percent neurodegeneration (r = 0.96, p < 0.001). These findings indicate there is regionally specific neurodegeneration 24 h after exposure to soman. The high correlation between T2 relaxivity and histopathology supports the use of T2 as a marker of injury.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Globally, there are up to two million cases of acute pesticide poisoning annually1. Organophosphorus (OPs) compounds are one of the most widely used pesticides and account for 33% of the pesticides used within the United States in 20122. Although new regulations have led to a decrease in OP usage in the United States from 20002, pesticide self-poisoning remains a global health problem in low to middle income countries1. The ingestion of OPs may account for over 100,000 deaths per year1. More potent forms of OPs include nerve agents that have been developed as chemical warfare agents. Confirmed usage of nerve agents in Syria, in 2013 and 2017, accounted for the death of hundreds of civilians whilst injuring thousands3. Nerve agents including tabun, sarin, soman, and VX continue to pose a threat to both civilians and military personnel. Exposure can lead to lacrimation, miosis, tremor, paralysis, convulsive seizures, and respiratory failure, often leading to death if untreated4.

A key problem is that following nerve agent exposure, assessing the extent of brain injury is difficult. A non-invasive method that is sensitive to nerve agent related pathology would allow for the monitoring of patients and determining the efficacy of nerve agent treatment protocols. Current treatment protocols are effective in protecting against lethality; however, they may not prevent nerve agent-related neuropathology and associated long-term sequelae. MRI has been used to assess brain pathology post OP exposure5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12 but few studies have directly correlated the MR changes to histopathology7,8,10. Diffusion MRI provides contrast that relates to cell swelling, changes to myelin, and water content13. In models of OP exposure, diffusion MRI has shown contrast that correlates with histological damage detected with hematoxylin and eosin7,8 or hemalun-phloxine10, and neuroinflammation detected with ionized calcium binding adaptor molecule 1 (IBA1) and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)8. The main contributor to nerve agent-related neurological damage is believed to be from prolonged nerve agent-induced seizure activity14. Nerve agents irreversibly inhibit acetylcholinesterase which leads to hyperactivity of cholinergic neurons in the piriform cortex and medial septum15. This hyperactivity initiates a cascade that recruits glutamatergic neurons in the temporal lobe causing the onset of seizures4,16. Prolonged nerve agent-induced seizures have been shown to cause consistent damage in the cerebral cortex, piriform cortex, amygdala, thalamus, and hippocampus17.

Quantitative T2 imaging (qT2) can be used to study the neuropathology following soman-induced convulsive seizures as it is sensitive to the changes in water content (edema) in the brain microstructure. Previous T2 relaxivity studies using soman have mainly focused on using signal intensity7,9 or change in T2 time5,6 to identify regions of damage followed by histology to validate the damage5,6,7,9. However, there have been no studies published that have attempted to correlate T2 relaxivity to the percentage of neurodegeneration following soman exposure.

This study used quantitative T2 MRI to correlate the severity and regional specificity of neurodegeneration following soman exposure. Soman is typically used to study the neuropathology of nerve agents since it is the fastest aging (form an irreversible bond with acetylcholinesterase) nerve agent18 and produces consistent convulsive seizures in defined models. Aging occurs within 2–3 min compared to hours for other nerve agents18, which introduces complexity in treating soman exposure. Therefore, treatments that are effective against soman are often effective, if not more so, against other nerve agents19.

The first objective of the study was to use qT2 MRI to identify structural changes in the brain 1 h and 18–24 h after a convulsive dose of soman. The second objective was to correlate the changes in qT2 MRI to the severity of neurodegeneration using histology. We hypothesized that soman-induced convulsive seizures would cause edematous injury and neurodegeneration within 24 h that could be consistently detected using qT2 MRI. Establishing the sensitivity of qT2 MRI to soman-related neuropathology will be useful as a diagnostic biomarker and facilitate the application to examining the efficacy of treatments in the future.

Methods

Experimental design

Previously, we determined that 90 µg/kg (subcutaneous) of soman consistently induced convulsive seizures in a rodent model20. HI-6 dimethanesulfonate (HI-6) (125 mg/kg) and atropine methyl nitrate (AMN) (20 mg/kg), were dissolved in saline, and given as pre- and post-treatment (volume of 1 ml/kg; intraperitoneal) to reduce peripheral soman-related symptoms thereby increasing animal throughput. HI-6 reactivates AChE by breaking the phosphate bond between AChE and soman before the aging process21. AMN is a competitive inhibitor of ACh at muscarinic receptors, which reduces peripheral cholinergic symptoms22. HI-6 and AMN are poor at crossing the blood–brain barrier (BBB), hence have minimal therapeutic benefit for seizure control.

For MRI, rats (n = 23) were anaesthetized with a mixture of 1–2.5% isoflurane, delivered in 70% nitrogen and 30% oxygen. Baseline qT2 MRI was performed using a 9.4 T MRI at least 24 h prior to saline or soman treatment. Pre-treatment was administered 20 min prior to soman exposure. For safety during soman exposure, rats were lightly anaesthetized with isoflurane for a maximum of 2–3 min and injected (25G 5/8 needle, volume of 0.4 ml/kg) subcutaneously with soman (90 µg/kg) at the scruff of the neck. The injection site was immediately decontaminated with Reactive Skin Decontamination Lotion and the rat was placed in an observation cage. Rats were observed for the development of soman-related symptoms based on the Suffield rating scale20 and behavioral seizures using the Racine scale23. An additional three doses of the post-treatment regimen were administered at 20-min intervals (intraperitoneal).

Separate groups of soman treated rats were imaged at 1 h (n = 9) or 18–24 h (n = 10) after exposure. Rats that were given saline were imaged at 1 h and 24 h (n = 4). To account for the neuroprotective properties of isoflurane24, the brain tissues of soman treated rats were preserved through fixation (see “Tissue preparation and histology” section) immediately after imaging. The brain tissues of saline treated rats were collected at 24 h. Fluoro-Jade C histochemistry was performed and level of staining quantified as an indicator of neurodegeneration.

Animals

Animal care protocols were approved by the University of Calgary Animal Care committee and met the Canadian Council of Animal Care (CCAC) guidelines. Rats were closely monitored daily by qualified staff to ensure animal welfare standards were maintained.

Male Sprague–Dawley rats, weighing 240–300 g, were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Montréal, QC, Canada). Rats were housed in pairs at the University of Calgary Animal Care Facility (Calgary, AB, Canada) in an environmentally controlled room on a 12-h light/dark cycle. Access to food and water ad libitum. All experiments were performed following a minimum acclimatization period of 5 days in their new environment and to human interactions.

Soman and treatments

(±) Soman (O-pinacolyl methylphosphonofluoridate; CAS 96-64-0), HI-6 dimethanesulfonate (CAS 144252-71-1), and Reactive Skin Decontamination Lotion were provided by the Defence Research and Development Canada Suffield Research Centre. Atropine Methyl Nitrate (CAS 52-88-0) was purchased from Sigma Aldrich (Milwaukee, WI, USA).

Symptom and seizure evaluation

The Suffield Rating Scale was used to evaluate soman-related symptoms20 while the Racine scale was used to measure behavioral seizures23. Rats treated with soman were monitored and rated every 10 min for up to 2 h. If the rats were rated 4 or higher on the Suffield Rating Scale, additional observations were required until an improvement was observed for at least two consecutive observation periods.

MRI parameters and analysis

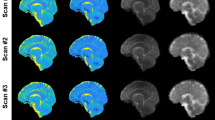

MRI was performed using a 9.4 T Bruker Avance console (Bruker Biospin GmbH, Rheinstetten, Germany) with a 35-mm quadrature volume coil. Rats were anaesthetized with 1–2.5% isoflurane, in 70% nitrogen and 30% oxygen. An in-house built restraining system including ear bars and a bite bar that was used to secure the head and prevent motion artifacts. Scanning protocol involved a multi-slice multi-echo T2 sequence: TR = 6,534 ms, 32 echoes were collected with 10 ms echo spacing, 1 average, 20 slices, field of view = 30 × 30 mm2, and matrix size = 128 × 128, voxel size = 0.23 × 0.23 × 0.8 mm3. Respective baseline images were obtained for each rat followed by either saline or soman injection (Fig. 1). Throughout the image acquisition, temperature and respiration rate were monitored and maintained at normal physiological range (approximately 36.5 °C and 60 breaths per minute).

Representative coronal images of the fourth echo (40 ms), (A) baseline and (B) 18–24 h after soman injection. (C) Comparison of baseline, saline, 1 h after soman, and 18–24 h after soman. At 18–24 h after soman exposure, extensive hyperintensive regions were observed in the piriform cortex, cerebral cortex, amygdala, and thalamus (colored arrows). Additionally, ventricular enlargement was seen 18–24 h after soman exposure.

Multiexponential T2 analysis was performed using AnalyzeNNLS (https://sourceforge.net/projects/analyzennls/), which is a compilation of open source MATLAB scripts25. The T2 relaxation curve was mapped starting with the second echo due to complications with the stimulated echoes. Tissue heterogeneity produces a decay curve composed of multiexponential components. The different components in a multiexponential decay curve can be analyzed by Eq. (1)26:

where ti is the echo time, M = 120 which are the logarithmically spaced T2 times between 5 to 640 ms, N = 32 which represents the total number of echoes, and sj represents the relative signal amplitude at the partitioned T2 time (T2j). The analysis utilizes a non-negative least square (NNLS) algorithm to minimize misfit and smoothing constraint for the T2 distribution. This provides a more consistent fit when noise is present26,27. We defined the area under the amplitude of the T2 curve as three different water compartments depending on the T2 values. We used the range of T2 < 25 ms for myelin associated water, T2 of 25–200 ms for intra/extracellular water, and T2 > 2000 ms for cerebrospinal fluid.

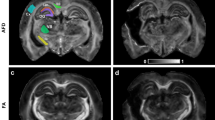

A rat brain atlas28 was used as a reference to manually draw the corresponding regions of interest in the qT2 images. Signal changes before and after exposure were measured in the piriform cortex, basolateral amygdala, medial amygdala, medial thalamus, dorsolateral thalamus, cerebral cortex, and retrosplenial cortex. Representative T2 fitting and distribution before and 18–24 h after soman-induced seizures in the piriform cortex can be seen in Fig. 2.

Representative T2 fitting and distribution before (A,B) and 18–24 h after a convulsive dose of soman (C,D) in the piriform cortex. A, signal intensity decayed by 250 ms. B, the mean geometric T2 distribution was 48 ms. (C) 18–24 h after soman higher signal intensity was detected with the signal decay by 320 ms. (D) 18–24 h after soman the mean T2 distribution was 93 ms which widened and shifted to the right.

Tissue preparation and histology

Rats were deeply anaesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (200 mg/kg; intraperitoneal) immediately following MRI. To preserve the brain tissue, rats were intracardially perfused with 150 ml of cold 1% phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fixed with 200 ml of 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) solution. Brains were extracted and stored in 4% PFA for 24 h at 4 °C then transferred to a 30% sucrose solution for long-term storage. The brains were sliced to 25 μm thickness using a cryostat (Leica, Biosystems). Slices were placed on electrostatically charged slides and stored at − 80 °C.

To determine the number of neurons in control tissue, saline treated rats were stained for Neuronal Nuclei (NeuN) (no. ab177487, Abcam Inc, ON, Canada). The slides were removed from the freezer and air dried for 30 min. The slides were then incubated for 1-h in a blocking serum composed of 10% horse serum, 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 0.1% cold fish skin gelatin (CFSG), 0.5% Triton X-100, and 0.05% Tween-20 in 1 × PBS. Following incubation slides were rinsed in a 0.05% Tween-20 solution in 1 × PBS for 10 min. The primary antibody NeuN, diluted with 5% horse serum, 1% BSA, 0.1% CFSG, and 0.5% TritonX-100 in 1 × PBS, was applied on the slides for 12-h. Slides were once again rinsed in 0.05% Tween-20 in 1 × PBS for 10 min. The secondary antibody Alexa Fluor 594 (no. 711-585-152, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc, PA, USA) was diluted in 1% BSA, 0.1% CFSG, and 1% TritonX-100 solution in 1 × PBS. Slides were incubated with the secondary antibody for 1-h and rinsed in 0.05% Tween-20 in 1 × PBS for 10 min. Throughout the secondary incubation and all subsequent steps, the slides were kept in a dark environment at room temperature. Slides were then fitted with coverslips using Immuno-Mount (Thermo Scientific, ON, Canada).

Tissues were stained using Fluoro-Jade C (no. AG325, Millipore, ON, Canada), which has been shown to selectively stain for degenerating neurons29. Frozen sections were rehydrated followed by incubation in 0.06% KMnO4 for 20 min. The sections were then drained and rinsed for 2 min with distilled water followed by incubation in 0.00001% Fluoro-Jade C (FJC) solution for 20 min. Following incubation slides were rinsed three times in distilled water and dried with a hair dryer for 5 min in a dark environment. Dried slides were placed in xylene for 5 min, and cover slipped with dibutylphthalate polystyrene xylene (DPX) mounting medium (Sigma Aldrich, Milwaukee, WI, USA).

Quantification of NeuN and FJC

A rat brain atlas28 was used to determine the counting frame in FJC and NeuN stained slices. The stained sections were visualized using the Olympus BX61-DSU microscope. FJC was viewed with a fluorescein isothiocyanate filter at 450–490 nm and NeuN was viewed with a tetramethylrhodamine filter at 488–532 nm. The images were taken using a high-resolution digital camera from MBF Bioscience (Williston, VT, USA). Quantification of FJC and NeuN positive cells was performed manually using Stereo Investigator (version 11, MBF Bioscience). Regions of interests were identified at × 10 magnification (Numerical aperture = 0.24). The counting frame was 400 × 400 μm2 in the regions of interest. The FJC and NeuN positive cells per area were calculated via number of cells over the area of the counting frame.

To quantify and compare the extent of neurodegeneration, the heterogeneity in cells per area between regions must be accounted for. As such, we calculated the percentage of neurodegeneration by comparing the FJC and NeuN positive cells per area.

Statistics

All statistical analyses were performed using R 3.5.030 or MATLAB 2018a Statistics and Machine Learning Toolbox (Mathworks, Natick, MA, US). There were three groups (saline, 1 h after soman, and 18–24 h after soman), each imaged twice before and after saline or soman exposure. A general linear model was performed evaluating the changes in T2 after exposure. Group (saline, soman 1 h, soman 18–24 h), treatment (before, after exposure), and brain regions were entered as fixed effects. This was followed by Tukey’s honestly significant difference post-hoc test. For the linear regression, the relaxation rate (R2) was calculated using \(R_{2}=1/T_{2}\). The relationship between changes in R2 vs. percentage of neurodegeneration was determined through linear regression to calculate the correlation coefficient (r), and equation of the line. We excluded one rat from the linear regression because tissues did not adhere to the slides and FJC staining could not be assessed. Statistical significance was determined a priori using α = 0.05.

Results

Consistent with our previous study20, rats (n = 19) exposed to soman developed generalized tonic–clonic seizures within 7–21 min post exposure. These rats continued to exhibit intermittent mild tremors with rhythmic head movement until imaging at 1 h (n = 9) or 18–24 h (n = 10). As expected, rats (n = 4) treated with saline did not exhibit behavioral abnormalities.

To consider qT2 MRI as an accurate depicter of brain damage following soman-induced seizures, the images that it produces need to clearly depict the regions of damage. Compared to the baseline (Fig. 1A), at 18–24 h after soman exposure we found clearly defined hyperintensive regions in the basolateral amygdala, medial amygdala, dorsolateral thalamus, medial thalamus, and piriform cortex (Fig. 1B). Whereas more subtle hyperintensity was observed in the cerebral cortex and retrosplenial cortex (Fig. 1B). The cohort 18–24 h after soman had notable changes that were easily identifiable, while there were no observable changes in saline treated and 1 h after soman exposure groups (Fig. 1C). As there were substantive changes found 18–24 h after soman exposure, the change in T2 relaxation time was quantified in the regions of interest, using a multiexponential T2 decay analysis.

Multiexponential T2 analysis was used to obtain the T2 distribution and decay curves because it provides enhanced pathological specificity compared to a monoexponential T2 analysis31. A representative analysis using the piriform cortex as an example is shown in Fig. 2. As expected, at 18–24 h after soman exposure the T2 distribution was higher and wider with a rightward shift (Fig. 2B,D). The baseline had a geometric mean T2 of 48 ms (Fig. 2B) while 18–24 h after soman exposure the T2 was 93 ms (Fig. 2D). We did not see any peaks between 200 and 2000 ms, which is consistent with previous observations32,33,34.

We quantified the changes in T2 relaxation time after soman-induced seizures to determine the damage in the regions of interest (Table 1). There was a three-way interaction between group, treatment, and brain region (F12, 280 = 11.71, p < 0.001). Post-hoc test was performed and revealed that there was no significant change pre and post saline exposure (n = 4) in every brain region (Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. S1). Additionally, at 1 h after soman exposure (n = 9) there was no significant change before and after soman in regions of interest (Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. S1). At 18–24 h after soman exposure (n = 10), there was a significant increase in T2 in the basolateral amygdala by 36% (t = 14.8, df = 280, p < 0.001), dorsolateral thalamus by 35% (t = 12.5, df = 280, p < 0.001), and piriform cortex by 42% (t = 20.5, df = 280, p < 0.001) (Fig. 3). A significant increase in T2 was also found in the cerebral cortex by 20% (t = 5.8, df = 280, p < 0.001), medial amygdala by 21% (t = 7.3, df = 280, p < 0.001), and medial thalamus by 29% (t = 10.2, df = 280, p < 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. S1). Quantification of T2 reveals that the piriform cortex had the most severe damage followed by the basolateral amygdala and dorsolateral thalamus.

The effects of soman exposure on T2 relaxation time before exposure, 1 h after soman (n = 9), or 18–24 h after soman (n = 10). (A–C) there was no significant difference 1 h after soman exposure from the respective baseline. There was a significant difference 18–24 h after soman exposure from the respective control in the basolateral amygdala (t = 14.8, df = 280, p < 0.001), dorsolateral thalamus (t = 12.5, df = 280, p < 0.001), and piriform cortex (t = 20.5, df = 280, p < 0.001). There was no significant difference in the saline treated group (n = 4). Rats were imaged at least 24 h before treatment. Black bars are the maximum and minimum T2 time. Middle black line is the median and the plus signs are outliers. The baseline for each group served as their own respective control. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Using FJC, which is a stain for neurodegeneration29, we validated the damage found in the regions of interest when using qT2 MRI. The qualitative assessment suggests that there was no neurodegeneration in saline treated rats or in rats examined 1 h after soman exposure (Fig. 4, Supplementary Fig. S2). While at 18–24 h after soman exposure, there were a high number of FJC positive cells in the regions of interest (Fig. 4, Supplementary Fig. S2). To quantify this observation, we analyzed the FJC positive cells per area in the regions of interest (Table 1). We found the medial amygdala had the highest neurodegeneration per area of 747 ± 205 cells per mm2 (mean ± SD) while the retrosplenial cortex had the lowest neurodegeneration per area of 291 ± 110 cells per mm2. However, when the heterogeneity in cells per area between regions were accounted for, using NeuN, we found the piriform cortex had the highest percentage of neurodegeneration of 76% while the cerebral cortex had the lowest percentage of 23%. These finding suggests there may be heterogeneity in the progression of neurodegeneration that are region dependent and are not reflective of the T2 relaxation time.

Effect of soman-induced seizures on neuronal cells following 18–24 h after soman exposure in the cerebral cortex, medial amygdala, and piriform cortex. Rats were perfused and fixed immediately after MR imaging and stained using Fluoro-Jade C, which is a marker for neurodegeneration. Fluoro-Jade C positive cells were manually quantified in regions corresponding to the T2-weighted MR images.

To determine the efficacy of qT2 MRI in delineating soman-related brain damage, the changes in the relaxation rate (R2 = 1/T2) were correlated to the percentage of neurodegeneration in regions of interest. The percentage of neurodegeneration was used to account for heterogeneity between regions. We correlated with R2 as the relaxation rate changes linearly with factors that influence relaxation of water35. Since there were no FJC positive cells in saline treated or 1 h after soman exposure, only the 18–24 h after soman exposure group (n = 9) was analyzed. There was a significant correlation in the cerebral cortex (r = 0.86, p = 0.003 with a slope of 0.013), medial amygdala (r = 0.86, p = 0.003 with a slope of 0.006), and piriform cortex (r = 0.96, p < 0.001 with a slope of 0.008) (Fig. 5). Additional correlations are shown in the supplementary information: dorsolateral thalamus (r = 0.76, p = 0.02, with a slope of 0.014), and medial thalamus (r = 0.78, p = 0.014 with a slope of 0.0065) (Supplementary Fig. S3). Notably, there was no significant correlation in the basolateral amygdala (r = 0.07, p = 0.87 with a slope of 4.99 × 10–4), and retrosplenial cortex (r = 0.63, p = 0.07 with a slope of 0.004). The piriform cortex had the highest correlation coefficient of 0.96 followed by the cerebral cortex and medial amygdala with a correlation coefficient of 0.86.

Effect of soman-induced seizures on the rate of relaxation (R2) correlated to the percentage of neurodegeneration in the cerebral cortex, medial amygdala, and piriform cortex. (A–C) significant correlation was found in the cerebral cortex (r = 0.86, p = 0.003), medial thalamus (r = 0.86, p = 0.003), and piriform cortex (r = 0.96, p < 0.001). Each point represents one rat.

A potential challenge in predictive MRI is the inter-subject variability. The heterogeneity of T2 relaxation times in the baseline was within 2 ms in each brain region, which is a coefficient of variation of less than 6%. At 1 h after soman exposure, when no neurodegeneration was observed, the standard deviation was 2.2 ms, which is a coefficient of variation less than 5%. When high levels of neurodegeneration were noted, at 18–24 h after soman, the standard deviation was 13.4 ms, with a coefficient of variation of 16%.

Discussion

T2 has been widely used in MRI to detect major changes in water content and tissue pathophysiology in preclinical models such as cancer36,37 and stroke38,39. Much of the previous T2 related literature quantifies T2 using less than seven echo times to describe a relaxation curve following soman exposure5,6,12. In order to quantify the T2 more accurately, more echoes were utilized to fit the decay curve. The brain is a heterogeneous structure mainly composed of water, lipids, and proteins. The decay curve can be processed as a multiexponential function to describe different T2 components representative of the microstructures in the brain. The complex nature of the different water environments results in multiple T2 decay times within a single voxel. In utilizing a NNLS T2 fitting algorithm, the T2 decay curve can be separated into the respective water compartments that contribute to the total T2 signal. Analysis using NNLS algorithm is advantageous as it makes no assumptions a priori on the number of water compartments that make up the T2 decay curve26. Therefore, rather than assuming a set number of water compartments through a few number of exponentials, NNLS can analyze relaxation data in a continuous model26. Compared to a discrete spectrum a continuous spectrum considers slow and fast decaying protons in addition to intermediate decaying protons, which may arise from an interaction between compartments40, thereby better modelling biological samples. In a healthy brain with high signal to noise, three components are commonly seen, a short component associated with myelin water, a medium component associated with intra/extracellular water, and a long component associated with CSF31,32,34. Although a healthy brain can be accurately modelled with three components, in pathological states, having a large number of relaxation components can provide a more accurate overview on the changes in microstructures. For a discussion on the pros and cons of using NNLS see paper by Whittall and MacKay26.

In our study, we rarely saw a short T2 component in the grey matter. This component has been attributed to water interacting with myelin or myelin water fraction34. It is common in animal studies to only detect one component in the grey matter. This is because of the low myelin content32. This study focused on detecting cerebral edema as well as the pathophysiology of tissue damage in the grey matter following soman exposure.

At 18–24 h post-soman exposure, rats had cerebral edema and neurodegeneration in the amygdala, cerebral cortex, piriform cortex, and thalamus based on increases in T2. These findings correspond with previous studies where cerebral edema was observed 24 h after OP-induced seizures5,6,7,10,11,12,17 and is thought to be a combination of both cytotoxic and vasogenic edema11. The edema following soman-induced seizures likely developed from the damage sustained through excitotoxicity41,42,43, oxidative stress44,45 and neuroinflammation46,47,48. When the neurons are unable to recover from the damage, they undergo degeneration. This corresponds to our study where the edematous regions showed extensive neurodegeneration using FJC (Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. S2). FJC staining was used to assess neurodegeneration as this stain shows specificity towards degenerating neurons29. Normalization using NeuN has shown the piriform cortex to have the highest level of neurodegeneration, which is similar to what was observed using qT2. Therefore, we speculate that the extent of neurodegeneration may mediate cerebral edema.

T2 is often used as a marker of edema but it also shows changes in cell pathophysiology. The strong correlation with FJC indicates that either edema strongly correlates with neurodegeneration or that T2 is detecting changes from two processes, cell integrity and edema. Regardless, qT2 is proving to be a sensitive metric of neurodegeneration associated with edema. Based on a study using sarin, changes in the BBB occurs as early as 2 h but leakage does not occur until 24 h49. The severity of localized BBB disruption may be proportional to the inflammatory cytokines released from degenerating neurons following soman-induced seizures. Cytokine release including interleukin (IL)-6, IL-1 α, IL-1 β, and tumor necrosis factor- α following soman-induced seizures48,50 were found to increase the permeability of the BBB51. The increased permeability may allow neutrophil infiltration, which can further exacerbate the initial injury and cause BBB leakage. The piriform cortex was shown to have a high number of neutrophil infiltrations at 24 h following soman-induced seizures47 which matches the time point where vasogenic edema is expected to occur. A study using a nerve agent substitute, diisopropyl fluorophosphate, found a correlation between diffusion MRI (apparent diffusion coefficient) and neuronal necrosis and neuroinflammation8. Thus, the vasogenic edema that we observed at 18–24 h may be mediated through neuroinflammation. As a result, we were able to demonstrate that qT2 was able to detect the severity of neurodegeneration non-invasively.

The high degree of correlation between R2 and neurodegeneration following soman exposure demonstrates the feasibility of qT2 MRI as a marker of injury (Fig. 5, Supplementary Fig. S3). The cerebral cortex, medial amygdala, and piriform cortex showed consistent pathology with T2 (Fig. 3, Supplementary Fig. S1) and histology (Fig. 4, Supplementary Fig. S2). However, there appears to be significant regional specificity of neurological damage following soman-induced seizures. In particular the piriform cortex had the highest correlation between R2 and percent neurodegeneration among the regions of interest (Fig. 5c). The difference in the level of predictability may be due to the regional susceptibility to seizures or the time course for the development of neuropathology. The piriform cortex was speculated as the site of seizure onset following OP exposure15 which may allow more time for edema to develop. This region has been shown to also play an important role in initiating and mediating seizure activity in rodents52. Based on qT2, regional differences in the pathophysiology post soman exposure, and changes in T2 that are proportional to the magnitude of neurodegeneration can be clearly detected. This method of imaging can be useful for diagnosis of nerve agent mediated brain injury, assessment of efficacy of novel treatments, and provide a critical time course of recovery.

One might expect that the early time course of T2 could be predictive of long-term pathology. Prior to this study, the earliest time point following soman-induced seizures where T2 was measured was 3 h12,13 and 6 h32. No changes were reported5,6,12. We also found no significant reduction in T2 1 h after soman, although there was a trend in the cerebral cortex and basolateral amygdala. Interestingly, a study in a febrile seizure model found a decrease in T2 in the basolateral amygdala two hours post seizures53. A decrease in T2 in the basolateral amygdala was predictive of epileptogenesis53. Spontaneous recurrent seizure have also been detected following soman exposure54.

The decrease in T2 found in febrile seizure model may be due to hypoxia, which results in an increase in deoxyhemoglobin55. We have previously found a decrease in cerebral blood flow throughout the brain 1-h after soman exposure56. Despite such a decrease in cerebral blood flow either from neurovascular uncoupling57 or transient vasoconstriction20,58, T2 did not change. The growing evidence of physiological changes at this time point suggests that early changes in T2 may be difficult to detect.

The present study demonstrates the value of qT2 MRI as a marker for neurodegeneration following OP exposure. The extent of neurodegeneration from seizures are often difficult to determine as the pathologies are transient. MRI non-invasive characteristics has the advantage that it could be undertaken over a time course which would help describe regional progression of injury. We suggest that qT2 MRI, as a non-invasive assessment of acute OP toxicity, has the potential to be a paradigm for determining the effectiveness of treatments aimed at reducing OP related neuropathology. Previous studies have found the neurodegeneration to be the highest at 24 h following OP exposure17. Therefore, reducing damage within that time frame may be critical in the prevention of long-term pathologies including the development of spontaneous recurrent seizures54,59.

Another area of interest may lie in the translational value of the results as a diagnostic marker. The similar symptomology of nerve agents with both cyanide poisoning and opioid overdose makes diagnosis difficult, especially when time is a critical factor60. In our results, we found the high level of changes in the piriform cortex. A closely related structure to the piriform cortex is the insular cortex in human. Victims of the 1995 Tokyo subway sarin attack had decreased brain volume in the insular and temporal cortex, 5 to 6 years following the attack61. A recent report on the Havana Syndrome, which suspects OP insecticide exposure, has found BBB leakage in the insular cortex62. Both of these studies were conducted using MRI and detected subtle changes. Therefore, we propose that detecting localized damage in the insular cortex using qT2 MRI may help clinicians to identify acute OP toxicity.

In the future, qT2 MRI should be used to acquire additional time points to elucidate the development of OP related neuropathology over time including both short- and long-term changes. Additionally, the development of neurodegeneration should be compared with other physiological measures including, seizure duration, serum acetylcholinesterase, cerebral blood flow, tissue oxygenation, and BBB leakage.

Using qT2 MRI, we demonstrated that T2 relaxation time was correlated to neurodegeneration following soman exposure. At 18–24 h after soman, we found that an increase in T2, which is indicative of cerebral edema, correlated with neurodegeneration. Although correlations were seen in many different regions, we found the highest correlation in the cerebral cortex, medial amygdala, and piriform cortex. The high degree of correlation and consistency of T2 relaxation time provide evidence that qT2 could be used as a biomarker for civilian and military personnel for nerve agent exposure.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Mew, E. J. et al. The global burden of fatal self-poisoning with pesticides 2006–15: Systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 219, 93–104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.05.002 (2017).

Atwood, D. & Paisley-Jones, C. Pesticides Industry Sales and Usage: 2008–2012 Market Estimates (US Environmental Protection Agency, Washington, DC, 2017).

Rodriguez-Llanes, J. M., Guha-Sapir, D., Schluter, B. S. & Hicks, M. H. Epidemiological findings of major chemical attacks in the Syrian war are consistent with civilian targeting: A short report. Confl. Health 12, 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-018-0150-4 (2018).

McDonough, J. H. Jr. & Shih, T. M. Neuropharmacological mechanisms of nerve agent-induced seizure and neuropathology. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 21, 559–579 (1997).

Bhagat, Y. A., Obenaus, A., Hamilton, M. G. & Kendall, E. J. Magnetic resonance imaging predicts neuropathology from soman-mediated seizures in the rodent. NeuroReport 12, 1481–1487 (2001).

Bhagat, Y. A., Obenaus, A., Hamilton, M. G., Mikler, J. & Kendall, E. J. Neuroprotection from soman-induced seizures in the rodent: Evaluation with diffusion- and T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Neurotoxicology 26, 1001–1013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuro.2005.04.006 (2005).

Rosman, Y. et al. Using MRI for the assessment of paraoxon-induced brain damage and efficacy of antidotal treatment. J. Appl. Toxicol. 32, 409–416. https://doi.org/10.1002/jat.1715 (2012).

Hobson, B. A. et al. From the cover: Magnetic resonance imaging reveals progressive brain injury in rats acutely intoxicated with diisopropylfluorophosphate. Toxicol. Sci. 157, 342–353. https://doi.org/10.1093/toxsci/kfx049 (2017).

Hobson, B. A. et al. A magnetic resonance imaging study of early brain injury in a rat model of acute DFP intoxication. Neurotoxicology 66, 170–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuro.2017.11.009 (2018).

Testylier, G. et al. Cerebral edema induced in mice by a convulsive dose of soman. Evaluation through diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging and histology. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 220, 125–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.taap.2007.01.013 (2007).

Carpentier, P. et al. Hyperosmolar treatment of soman-induced brain lesions in mice: Evaluation of the effects through diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging and through histology. Toxicology 253, 97–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tox.2008.08.016 (2008).

Gullapalli, R. P. et al. Magnetic resonance imaging reveals that galantamine prevents structural brain damage induced by an acute exposure of guinea pigs to soman. Neurotoxicology 31, 67–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuro.2009.09.004 (2010).

Hagmann, P. et al. Understanding diffusion MR imaging techniques: From scalar diffusion-weighted imaging to diffusion tensor imaging and beyond. Radiographics 26(Suppl 1), S205–S223. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.26si065510 (2006).

Myhrer, T., Enger, S. & Aas, P. Anticonvulsant efficacy of drugs with cholinergic and/or glutamatergic antagonism microinfused into area tempestas of rats exposed to soman. Neurochem. Res. 33, 348–354. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11064-007-9429-3 (2008).

Zimmer, L. A., Ennis, M., Wiley, R. G. & Shipley, M. T. Nerve gas-induced seizures: Role of acetylcholine in the rapid induction of Fos and glial fibrillary acidic protein in piriform cortex. J. Neurosci. 18, 3897–3908 (1998).

Shih, T. M. & McDonough, J. H. Jr. Neurochemical mechanisms in soman-induced seizures. J. Appl. Toxicol. 17, 255–264 (1997).

Baille, V. et al. Soman-induced convulsions: The neuropathology revisited. Toxicology 215, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tox.2005.05.028 (2005).

Worek, F., Thiermann, H., Szinicz, L. & Eyer, P. Kinetic analysis of interactions between human acetylcholinesterase, structurally different organophosphorus compounds and oximes. Biochem. Pharmacol. 68, 2237–2248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bcp.2004.07.038 (2004).

Shih, T. M., Duniho, S. M. & McDonough, J. H. Control of nerve agent-induced seizures is critical for neuroprotection and survival. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 188, 69–80 (2003).

Lee, K. et al. Assessment of brain oxygenation imbalance following soman exposure in rats. Neurotoxicology 65, 28–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuro.2018.01.007 (2018).

Jokanovic, M. & Stojiljkovic, M. P. Current understanding of the application of pyridinium oximes as cholinesterase reactivators in treatment of organophosphate poisoning. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 553, 10–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.09.054 (2006).

Shih, T. M., Koviak, T. A. & Capacio, B. R. Anticonvulsants for poisoning by the organophosphorus compound soman: Pharmacological mechanisms. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 15, 349–362 (1991).

Racine, R. J. Modification of seizure activity by electrical stimulation. II. Motor seizure. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 32, 281–294 (1972).

Krishnan, J. K. S. et al. Brief isoflurane administration as a post-exposure treatment for organophosphate poisoning. Neurotoxicology 63, 84–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuro.2017.09.009 (2017).

Bjarnason, T. A. & Mitchell, J. R. AnalyzeNNLS: Magnetic resonance multiexponential decay image analysis. J. Magn. Reson. 206, 200–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmr.2010.07.008 (2010).

Whittall, K. P. & MacKay, A. L. Quantitative interpretation of NMR relaxation data. J. Magn. Reson. 1969(84), 134–152 (1989).

Lawson, C. L. & Hanson, R. J. Solving Least Squares Problems (Siam, Philadelphia, 1995).

Paxinos, G. & Watson, C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates: Hard Cover Edition (Elsevier, Amsterdam, 2006).

Schmued, L. C., Stowers, C. C., Scallet, A. C. & Xu, L. Fluoro-Jade C results in ultra high resolution and contrast labeling of degenerating neurons. Brain Res. 1035, 24–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2004.11.054 (2005).

30R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2013).

MacKay, A. et al. Insights into brain microstructure from the T2 distribution. Magn. Reson. Imaging 24, 515–525. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mri.2005.12.037 (2006).

MacKay, A. et al. In vivo visualization of myelin water in brain by magnetic resonance. Magn. Reson. Med. 31, 673–677. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.1910310614 (1994).

Menon, R. S. & Allen, P. S. Application of continuous relaxation time distributions to the fitting of data from model systems and excised tissue. Magn. Reson. Med. 20, 214–227. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.1910200205 (1991).

Whittall, K. P. et al. In vivo measurement of T2 distributions and water contents in normal human brain. Magn. Reson. Med. 37, 34–43. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.1910370107 (1997).

Villringer, A. et al. Dynamic imaging with lanthanide chelates in normal brain: Contrast due to magnetic susceptibility effects. Magn. Reson. Med. 6, 164–174. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.1910060205 (1988).

Ali, T. S. et al. QuantitativeT2: Interactive quantitative T2 MRI witnessed in mouse glioblastoma. J. Med. Imaging (Bellingham) 2, 036002. https://doi.org/10.1117/1.JMI.2.3.036002 (2015).

Blasiak, B. et al. Detection of T(2) changes in an early mouse brain tumor. Magn. Reson. Imaging 28, 784–789. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mri.2010.03.004 (2010).

Hoehn-Berlage, M., Eis, M., Back, T., Kohno, K. & Yamashita, K. Changes of relaxation times (T1, T2) and apparent diffusion coefficient after permanent middle cerebral artery occlusion in the rat: Temporal evolution, regional extent, and comparison with histology . Magn. Reson. Med. 34(824), 834. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.1910340607 (1995).

van Dorsten, F. A. et al. Dynamic changes of ADC, perfusion, and NMR relaxation parameters in transient focal ischemia of rat brain. Magn. Reson. Med 47, 97–104. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.10021 (2002).

Zimmerman, J. R. & Brittin, W. E. Nuclear magnetic resonance studies in multiple phase systems: Lifetime of a water molecule in an adsorbing phase on silica gel. J. Phys. Chem. 61, 1328–1333. https://doi.org/10.1021/j150556a015 (1957).

Wade, J. V., Samson, F. E., Nelson, S. R. & Pazdernik, T. L. Changes in extracellular amino acids during soman- and kainic acid-induced seizures. J. Neurochem. 49, 645–650. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-4159.1987.tb02912.x (1987).

Lallement, G. et al. Neuroprotective activity of glutamate receptor antagonists against soman-induced hippocampal damage: Quantification with an omega 3 site ligand. Brain Res. 618, 227–237 (1993).

Guo, H. et al. N-acetyl-aspartyl-glutamate and inhibition of glutamate carboxypeptidases protects against soman-induced neuropathology. Neurotoxicology 48, 180–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuro.2015.03.010 (2015).

Pazdernik, T. L., Emerson, M. R., Cross, R., Nelson, S. R. & Samson, F. E. Soman-induced seizures: Limbic activity, oxidative stress and neuroprotective proteins. J. Appl. Toxicol. 21(Suppl 1), S87-94. https://doi.org/10.1002/jat.818 (2001).

Jacobsson, S. O., Cassel, G. E. & Persson, S. A. Increased levels of nitrogen oxides and lipid peroxidation in the rat brain after soman-induced seizures. Arch. Toxicol. 73, 269–273. https://doi.org/10.1007/s002040050616 (1999).

Johnson, E. A., Guignet, M. A., Dao, T. L., Hamilton, T. A. & Kan, R. K. Interleukin-18 expression increases in response to neurovascular damage following soman-induced status epilepticus in rats. J. Inflamm. (Lond.) 12, 43. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12950-015-0089-9 (2015).

Johnson, E. A. et al. Increased expression of the chemokines CXCL1 and MIP-1alpha by resident brain cells precedes neutrophil infiltration in the brain following prolonged soman-induced status epilepticus in rats. J. Neuroinflamm. 8, 41. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-2094-8-41 (2011).

Johnson, E. A. & Kan, R. K. The acute phase response and soman-induced status epilepticus: Temporal, regional and cellular changes in rat brain cytokine concentrations. J. Neuroinflamm. 7, 40. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-2094-7-40 (2010).

Abdel-Rahman, A., Shetty, A. K. & Abou-Donia, M. B. Acute exposure to sarin increases blood brain barrier permeability and induces neuropathological changes in the rat brain: Dose-response relationships. Neuroscience 113, 721–741 (2002).

Spradling, K. D., Lumley, L. A., Robison, C. L., Meyerhoff, J. L. & Dillman, J. F. 3rd. Transcriptional responses of the nerve agent-sensitive brain regions amygdala, hippocampus, piriform cortex, septum, and thalamus following exposure to the organophosphonate anticholinesterase sarin. J. Neuroinflamm. 8, 84. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-2094-8-84 (2011).

de Vries, H. E. et al. The influence of cytokines on the integrity of the blood-brain barrier in vitro. J. Neuroimmunol. 64, 37–43 (1996).

Piredda, S. & Gale, K. A crucial epileptogenic site in the deep prepiriform cortex. Nature 317, 623–625. https://doi.org/10.1038/317623a0 (1985).

Curran, M. M. et al. Epilepsy-predictive magnetic resonance imaging changes following experimental febrile status epilepticus: Are they translatable to the clinic?. Epilepsia 59, 2005–2018. https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.14561 (2018).

de Araujo Furtado, M. et al. Spontaneous recurrent seizures after status epilepticus induced by soman in Sprague-Dawley rats. Epilepsia 51, 1503–1510. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02478.x (2010).

Choy, M. et al. A novel, noninvasive, predictive epilepsy biomarker with clinical potential. J. Neurosci. 34, 8672–8684. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4806-13.2014 (2014).

56Lee, K. et al. Measuring the effect of soman, a seizure-inducing chemical warfare nerve agent, with simultaneous perfusion and brain oxygenation measurements. In 26th Annual Meeting of International Society of Magnetic Resonance Medicine 2018, p. 3605. Abstract (2018).

Scremin, O. U., Shih, T. M. & Corcoran, K. D. Cerebral blood flow-metabolism coupling after administration of soman at nontoxic levels. Brain Res. Bull. 26, 353–356 (1991).

Farrell, J. S. et al. Postictal behavioural impairments are due to a severe prolonged hypoperfusion/hypoxia event that is COX-2 dependent. Elife https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.19352 (2016).

Bar-Klein, G. et al. Imaging blood-brain barrier dysfunction as a biomarker for epileptogenesis. Brain 140, 1692–1705. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awx073 (2017).

Ciottone, G. R. Toxidrome recognition in chemical-weapons attacks. N. Engl. J. Med. 378, 1611–1620. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMra1705224 (2018).

Yamasue, H. et al. Human brain structural change related to acute single exposure to sarin. Ann. Neurol. 61, 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.21024 (2007).

Friedman, A. et al. Havana syndrome among Canadian diplomats: Brain imaging reveals acquired neurotoxicity. MedRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/19007096 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We thank our colleagues from the Defence Research and Development Canada- Suffield Research Centre (W7702-155719/A) for providing the materials necessary for the research. This work was supported by the Canadian Department of National Defence. Funding support for this study was provided by Canadian Institutes of Health Research (MOP-130495) and Natural Science and Engineering Research (RGPIN/03819-2014). A Brain Canada Platform grant partially supported the MRI.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.F.D. oversaw the project. K.L. designed and performed all experiments. S.B. provided soman, carried out exposure, and advised on the project. C.V. assisted in soman exposure. J.M. assisted in soman exposure. M.B. assisted in histology, MRI data analysis, and histology quantification. J.S.F. provided protocols for histology and advised on the project. G.C.T. advised on the project. K.L. wrote the main manuscript and prepared all of the figures with oversight from J.F.D. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, K., Bohnert, S., Bouchard, M. et al. Quantitative T2 MRI is predictive of neurodegeneration following organophosphate exposure in a rat model. Sci Rep 10, 13007 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-69991-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-69991-z

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.