Abstract

Photonic de Broglie waves offer a unique property of quantum mechanics satisfying the complementarity between the particle and wave natures of light, where the photonic de Broglie wavelength is inversely proportional to the number of entangled photons acting on a beam splitter. Very recently, the nonclassical feature of photon bunching has been newly interpreted using the pure wave nature of coherence optics [Sci. Rep. 10, 7,309 (2020)], paving the road to unconditionally secured classical key distribution [Sci. Rep. 10, 11,687 (2020)]. Here, deterministic photonic de Broglie waves are presented in a coherence regime to uncover new insights in both fundamental quantum physics and potential applications of coherence-quantum metrology.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The nonclassical feature of anticorrelation on a beam splitter (BS), known as Hong-Oh-Mandel dip or photon bunching, has been the heart of quantum mechanics in terms of quantum entanglement, which cannot be achieved by classical means1,2,3,4,5. Unlike most anticorrelation studies based on the statistical nature of light, a deterministic solution has been recently found in a coherence manner for a particular phase relation between two input fields impinging on a BS6. Owing to coherence optics with a phase control, the BS-based anticorrelation can be achieved in a simple Mach–Zehnder interferometer (MZI)6. One of the first proofs of MZI physics for quantum mechanics was for anticorrelation using single photons1. For the coherence version, unconditionally secured classical key distribution has been proposed recently7. Although the physics of the unconditionally secured classical key distribution is based on quantum superposition, i.e., indistinguishability in the MZI paths7, the key carrier is not a quantum particle but a classical coherent light compatible with current fiber-optic communications networks. As debated for several decades, fundamental questions about the quantum nature of light are still an on-going important subject in the quantum optics community8,9,10.

Here in this paper, the fundamental questions of “what is the quantum nature of light? and “what is the origin of nonclassicality?” are asked and answered in terms of photonic de Broglie waves (PBWs) in a pure coherence framework based on the wave nature of light. Due to the quantum property of linear optics such as a BS or MZI6, however, nonclassical light itself does not have to be excluded1. Thus, the present paper provides a general conceptual understanding of fundamental quantum physics as well as potential applications of coherence-quantum metrology to overcome single photon-based statistical quantum limitations such as an extremely low rate at the higher-order entangled photon-pair generation and practical difficulties of generating higher-order entangled photon pairs of NOON states11,12,13,14,15,16.

The photonic de Broglie wavelength \({\lambda }_{B}\) is a key feature of quantum mechanics regarding wave-particle duality and complementarity of the quantum nature of light, where classical physics is not capable of explaining such phenomena11,12,13,14,15,16. PBWs have been demonstrated using entangled photon pairs generated from a spontaneous parametric down conversion (SPDC) process, where \({\lambda }_{B}={\uplambda }_{0}/\mathrm{N}\), and \({\uplambda }_{0}\) (N) is the initial wavelength (number of entangled photons) of nonclassical light11,12,13,14,15,16. For example, a single-photon entangled pair on a beam splitter results in a PBW at \({\lambda }_{B}={\uplambda }_{0}/2\). Similarly, this is also the case for \({\lambda }_{B}={\uplambda }_{0}/4\) for a two-photon entangled pair13. Due to experimental difficulties of obtaining a higher-order entangled photon pair, however, the application of quantum PBWs has been severely limited so far, whose latest record is \({\lambda }_{B}={\uplambda }_{0}/18\) with N = 1816. By the same reasoning, quantum lithography and quantum sensing have also been limited17,18,19. In particular, no deterministic entangled photon pair generator exists.

In the present paper, deterministic control of PBWs using coherence-optics-based anticorrelation6 is presented for both fundamental physics and its potential applications to coherence-quantum metrology, where the order N in \({\lambda }_{B}\) is unbounded. The deterministic control of PBWs should beneficial to quantum sensors beyond the standard quantum limit. The deterministic controllability of higher-order PBWs is a breakthrough in the practical limitations of entangled photon-based conventional quantum metrology17,18,19. Most importantly, a more general understanding of the quantum nature of light is presented.

Results

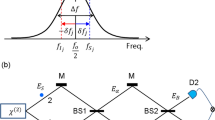

Figure 1 shows the basic building block of coherence PBWs using coherence optics-based anticorrelation. Figure 1a shows a deterministic scheme of anticorrelation with a phase shifter \({\psi }_{n}\) for photon bunching or a HOM dip on a BS6. The controlled phase \({\psi }_{n}\) is used to clarify statistical single photon-based anticorrelation1,2,3,4,5, where such anticorrelation on a BS must satisfy the definite phase between two input photons: \({\psi }_{n}=\pm \left(n-1/2\right)\pi\) for n = 1,2,3…6. Thus, the ambiguity in conventional anticorrelation on a BS has been thoroughly removed and applied for a deterministic nonclassical light generation. Because the BS matrix satisfies a π/2 phase shift between two split outputs, i.e., reflected and transmitted light20, Fig. 1a can be simply represented by a typical MZI as shown in Fig. 1b. Due to the preset π/2 phase shift on the first BS for E3 and E4 in Fig. 1b, the inserted phase shifter of \({\varphi }_{n}\) must be \({\varphi }_{n}=\pm n\pi\) for the same outputs as in Fig. 1a1, 6. The intensity correlation \({g}_{56}^{(2)}(\tau )\) between two outputs \({I}_{5}\) and \({I}_{6}\) is described by \({g}_{56}^{(2)}(\tau )=\frac{\langle {I}_{5}{\left(t+\tau \right)I}_{6}(t)\rangle }{\langle {I}_{5}(t+\tau )\rangle \langle {I}_{6}(t)\rangle }\), where \({I}_{j}\) is the intensity of \({E}_{j}\). Thus, conventional MZI becomes a quantum device for nonclassical photon generation with determinacy for Schrödinger’s cat or macroscopic NOON state generation1 (discussed below).

A basic unit of coherence PBW. a A BS-based anticorrelation scheme for photon bunching. b An equivalent scheme of (a). c A basic unit of coherence PBW. The input field E0 is coherent light. D or D’ indicates a MZI building block composed of beam splitters and a phase shifter. The coupled matrix of \({[D}{^{\prime}}][D]\) represents a coherence PBW scheme equivalent to quantum PBW with N = 4.

In conventional photon bunching phenomenon as exhibited in a HOM dip using SPDC-based entangled photon pairs, the requirement of \({\psi }_{n}\) in Fig. 1a is automatically satisfied by a closed-type \({\chi }^{(2)}\)-based three-wave mixing process in a nonlinear medium. In the SPDC nonlinear optical process, however, the choice of the sign of \({\psi }_{n}\) cannot be deterministic due to the bandwidth-wide, probabilistically distributed space-superposed entangled photons, e. g., as described by a polarization entanglement superposition state2: \(|\psi \rangle =\left({|H\rangle }_{1}{|V\rangle }_{2}+{{e}^{i\psi }|V\rangle }_{1}{|H\rangle }_{2}\right)/\sqrt{2}\). In the case of two independent solid-state emitters, the generated single photon pair can be phase-locked if excited by the same pump pulse. Thus, the condition of \({\psi }_{n}\) in Fig. 1a must be postadjusted to \(\pm \frac{\uppi }{2}\) for the relative phase difference for anticorrelation or entangled state generation3. The proof of the required phase of \(\pm \frac{\uppi }{2}\) in Fig. 1a for nonclassical light generation has already been demonstrated via two independent trapped ions21. In Fig. 1b, the spectral bandwidth \((\mathrm{\delta \omega })\) of the input light E0 should limit the interaction time (τ) or coherence length (\({l}_{C})\) in \({g}_{56}^{(2)}(0)\) anticorrelation. In the application of unconditionally secured communications7, the transmission distance is potentially unbounded on earth if a sub-mHz linewidth laser is used22: \({l}_{C}=\frac{c}{mHz}\sim {10}^{8} (km)\). In this case, a common phase encoding technique may be advantageous compared to the amplitude modulation method. According to ref. 23, the maximal indistinguishability induced by perfect quantum superposition represents maximal coherence, where maximal coherence is a prerequisite for an entangled pair or anticorrelation6.

Figure 1c presents the basic building block of asymmetrically coupled double-MZI (ACD-MZI) for a deterministic control of PBWs via coherence optics-based anticorrelation. The output fields in the first building block D of Fig. 1c, whether it is for E5 or E6, are fed into the second block D’ by splitting them into E7 and E8, resulting in a second-order superposition state. Here, the condition (basis) of anticorrelation in the MZI is \({\varphi }_{n}=\pm n\pi\), resulting in a distinctive output of either E5 or E6. The same phase shifter is used and simultaneously controlled in both D and D’ in an asymmetric configuration (see the phase shifter \(\Phi (\mathrm{\varphi })\) asymmetrically located). If the phase shifter distribution is symmetric, then a unitary transformation is satisfied for unconditionally secured classical cryptography7. The second-order superposition in Fig. 1c represents the fundamental physics of coherence PBWs. The output of the first block D in Fig. 1c is described as follows:

where \(\left[D\right]=\left[BS\right]\left[\Phi \right]\left[BS\right]\), \(\left[BS\right]=\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\left[\begin{array}{cc}1& i\\ i& 1\end{array}\right]\), and \(\left[\Phi \right]=\left[\begin{array}{cc}1& 0\\ 0& {e}^{i\varphi }\end{array}\right]\). Here, the output fields E5 and E6 are tolerant to fluctuations in phase, frequency, and intensity of the input field E0. As already known in MZI interferometry, Eq. (1) shows a \(2\pi\) modulation period for each output intensity: \({I}_{5}={I}_{0}\left(1-\mathrm{cos}(\varphi )\right)\); \({I}_{6}={I}_{0}\left(1+\mathrm{cos}(\varphi )\right)\) as shown in Fig. 2a. Thus, the intensity correlation \({g}_{56}^{\left(2\right)}(0)\) has a \(\pi\) modulation as expected (see the red curve in Fig. 2a):

Numerical calculations for \({g}_{ij}^{(2)}(\tau )\) intensity correlation of Fig. 1(c). a Red: \({I}_{5}{I}_{6}\) (normalized), Dotted: \({I}_{5}\), Dashed: \({I}_{6}\). b Red: IAIB (normalized), Dotted: \({I}_{A}\), Dashed: IB,. The input field intensity of \({E}_{0}=1\) is assumed.

where the phase basis for \({g}_{56}^{\left(2\right)}(0)=0\) is \({\varphi }_{n}=\pm n\pi\). Equation (2) provides a new understanding of nonclassical features, where perfect coherence plays a major role6. Equation (2) is also known as the classical resolution limit of Rayleigh criterion24.

The output lights, EA and EB, in the second block D′ of Fig. 1c are then described by the following matrix relation:

where \(\left[D{^{\prime}}\right]=\left[BS\right]\left[{\Phi }{^{\prime}}\right][BS]\) and \(\left[{\Phi }{^{\prime}}\right]=\left[\begin{array}{cc}{e}^{i\varphi }& 0\\ 0& 1\end{array}\right]\). Unlike Eqs. (1), (3) results in a twice shorter (faster) modulation period (frequency), i.e., a π modulation in each intensity of IA and IB: \({I}_{A}=\frac{1}{2}\left(1+\mathrm{cos}\left(2\mathrm{\varphi }\right)\right)\); \({I}_{B}=\frac{1}{2}\left(1-\mathrm{cos}\left(2\mathrm{\varphi }\right)\right)\) (see Fig. 2b). As a result, the intensity correlation \({g}_{AB}^{\left(2\right)}(0)\) of IA and IB becomes:

Thus, it has proved that the classical resolution limit of \({\lambda }_{0}/2\) governed by the Rayleigh criterion in Fig. 2a is overcome using coherence optics in the ACD-MZI scheme of Fig. 1c. This is the first analytic proof of such nonclassical features obtained by pure coherence optics. In Eq. (4), the phase basis for \({g}_{AB}^{\left(2\right)}(0)=0\) is accordingly changed from \({\varphi }_{n}=\pm n\pi\) in Fig. 2a to \({\varphi }_{n}=\pm n\pi /2\) in Fig. 2b. This doubly enhanced resolution of the output intensity in Eq. (4) contradicts our general understating on quantum mechanics because the method presented in Fig. 1c is perfectly coherent and classical.

Here, it should be noted that perfect correlation between two lights (E3/E4 or E7/E8) is achieved by path indistinguishability in MZI, and proved by either anticorrelation1,2,3,4,5,6 or Bell inequality violation25,26,27,28. Thus, the specific phase relation with \({\varphi }_{n}\) between two superposed coherent lights in MZI of Fig. 1b,c is the source of nonclassical features such as anticorrelation and entanglement6. In that sense, the number of superposition states in Fig. 1c should be equivalent to the number of entangled photons in conventional quantum PBWs (see Eqs. 2 and 4). Therefore, the ACD-MZI scheme of Fig. 1c represents the basic unit of the present coherence model of PBWs. As a result, higher-order coherence PBWs can be generated by simply connecting the asymmetrical units of Fig. 1c in a series (discussed in Fig. 3).

Figure 2 shows numerical calculations for Fig. 1c to support the present theory of deterministic control of PBWs in a coherence regime. Figure 2a shows a typical MZI result of Fig. 1b by solving Eq. (1), where each output intensity represents the classical limit. As expected, the conventional MZI scheme has a spectroscopic resolution of \({\uplambda }_{0}/2\), which is the Rayleigh limit in classical physics. This classical resolution limit is now understood as the first order of the present ACD-MZI PBWs: \({\lambda }_{CB}={\uplambda }_{0}/2\zeta\), where \(\upzeta\) is the number of MZI blocks (or superposition states in the form of Fig. 1b), and \({\lambda }_{CB}\) indicates the present coherence PBW. Here, it should be noted that each MZI block in Fig. 1c is equivalent to N = 2 in a quantum PBW11,12,13,14,15,16 for an entanglement superposition description of \(|\psi \rangle =\left({|N\rangle }_{A}{|0\rangle }_{B}+{|0\rangle }_{A}{|N\rangle }_{B}\right)/\sqrt{2}\): \(2\upzeta =\mathrm{N}\). In other words, a typical MZI is a quantum device for anticorrelation or nonclassical light generation if \({\varphi }_{n}=\pm n\pi\) is satisfied. The intensity correlation of \({g}_{AB}^{\left(2\right)}(0)\) in Eq. (4) is numerically calculated in Fig. 2b (see the red curve). The demonstration of \({\lambda }_{CB}={\uplambda }_{0}/4\) in Fig. 2b validates the present theory of coherence PBWs based on Fig. 1c. Thus, it is concluded that the present coherence PBW in Fig. 1c is equivalent to the quantum PBW11,12,13,14,15,16 based on entangled photons with the additional benefit of deterministic controllability.

For the higher order \({\lambda }_{CB}\), the basic scheme of Fig. 1c needs to be repeated in a row as shown in Fig. 3a. In a serial connection, the output from each block becomes two inputs for the next block without loss. Defining \(\left[CM\right]=\left[{D}{^{\prime}}\right]\left[D\right]\) with no loss, the nth output fields in Fig. 3a can be obtained from Eq. (3) as (see the Supplementary information):

From Eqs. (5–3) and (5–4) the related nth output intensities are obtained:

where \({I}_{0}={E}_{0}{E}_{0}^{*}\). Regardless of the chain length, the final output intensity is always the same as the input if optical loss is neglected. As a result, the intensity correlation \({g}_{n}^{\left(2\right)}(0)\) becomes:

where \({g}_{n}^{\left(2\right)}\left(0\right)\) represents for \({g}_{AB}^{\left(2\right)}(0)\) of the nth output in Fig. 3a. Thus, the general solution for the nth coherence PBW in Fig. 3a is:

where n is the number of ACD-MZI of Fig. 1c. For n = 1, it is equivalent to the four-photon (N = 4) case in quantum PBW11,12,13,14,15,16. Because Eq. (8) is deterministic, the coherence PBW is powerful compared with its conventional quantum counterpart in terms of N in the determinacy, controllability, and intensity. These facts may open the door to coherence-quantum metrology based on on-demand \({\lambda }_{CB}^{(n)}\). Compared with the impractical quantum PBWs, where it takes ~ 2 h of acquisition time just for N = 1816, the present coherence PBWs is unbounded in both N and power, and real time in processing due to coherence optics.

Figure 3a represents a serially connected ACD-MZI scheme, where each block is equivalent to Fig. 1c as a four-photon quantum PBW: \({\lambda }_{B} (=\frac{{\lambda }_{0}}{4})\). Regarding the connection lines, only one line is active for coherence PBWs, where the anticorrelation condition \({\varphi }_{n}=\pm n\pi\) is satisfied. If an error is found in the output intensity, that means the maximum superposition in MZI is broken and both lines are active. The error sharpness is the spectroscopic resolution of the coherence PBW for coherence-quantum metrology. To realize the schematic of Fig. 3a, a waveguide-coupled29 or a fiber-coupled30 MZI scheme would be a good example (see the Supplementary Information).

Figure 3b shows numerical calculations using Eq. (7) for the intensity correlation \({g}_{n}^{\left(2\right)}(0)\). As shown in Fig. 3b, the coherence \({\lambda }_{CB}^{(n)}\) is equivalent to the quantum \({\lambda }_{B}\). Compared with a quantum PBW11,12,13,14,15,16, the coherence PBW at \({\lambda }_{CB}^{(n)}\) is deterministic, macroscopic, functioning in real time, and boundless on N. Each intensity modulation period for \({\left({I}_{A}\right)}^{n}\) or \({\left({I}_{B}\right)}^{n}\) is twice as long as \({g}_{n}^{\left(2\right)}(0)\), as shown in Eqs. (6–1) and (6–2).

Conclusion

In conclusion, the deterministic control of photonic de Broglie waves (PBWs) was presented based solely on coherence optics for both fundamental physics and potential applications of quantum metrology using a chain of ACD-MZIs. For this, the output from each ACD-MZI was directly inserted into the next one until reaching the given n, where n indicates the number of ACD-MZIs. The analytical expressions and their numerical calculations successfully demonstrated the nonclassical features equivalent to quantum PBWs, where the number of MZIs in the coherence PBWs is equivalent to the entangled photon number N in quantum PBWs. The random phase noise of the MZI system caused by mechanical vibrations, air turbulence, and temperature variations at \(\le\) MHz may be eliminated or minimized through the use of either silicon photonics or fiber-optic technologies. Both stability and linewidth of the input light should act as the bound of coherence PBWs, limiting MZI fringe resolution. Thus, a fine-tuned laser such as sub-mHz laser should provide a higher n for shorter PBWs31. As a result, the proposed coherence PBW can be directly applied to high-precision optical spectroscopy or quantum metrology such as optical clocks32, gravitational wave detection33, quantum lithography17,18, and quantum sensors19. The seemingly contradictory aspect of coherence PBWs with quantum physics is reconciled via the quantum superposition of MZI paths, where MZI is treated as a quantum device like a BS if the appropriate phase is satisfied1,6. Thus, the present scheme of Fig. 3a may open the door to coherence-quantum metrology for deterministic control of photonic de Broglie wavelengths at higher orders in real-time and on-demand settings. Eventually, the present coherence photonic de Broglie wave generation scheme may be applied to non-classical light generation, such as deterministic entangled photons and photonic qubits, resulting in on-demand quantum information processing in a macroscopic regime.

References

Grangier, P., Roger, G. & Aspect, A. Experimental evidence for a photon anticorrelation effect on a beam splitter: a new light on single-photon interference. Europhys. Lett. 1, 173–179 (1986).

Hong, C. K., Ou, Z. Y. & Mandel, L. Measurement of subpicosecond time intervals between two photons by interference. Phys. Rev. Lett. 59, 2044–2046 (1987).

Lettow, R. et al. Quantum interference of tunably indistinguishable photons from remote organic molecules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 123605 (2010).

Peruzzo, A., Shadbolt, P., Brunner, N., Popescu, S. & O’Brien, J. L. A quantum delayed-choice experiment. Science 338, 634–637 (2012).

Deng, Y.-H. et al. Quantum interference between light sources separated by 150 million kilometers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 080401 (2019).

Ham, B. S. The origin of anticorrelation for photon bunching on a beam splitter. Sci. Rep. 10, 7309 (2020).

Ham, B. S. Unconditionally secured classical cryptography using quantum superposition and unitary transformation. Sci. Rep. 10, 11687 (2020).

Bohr, N. The quantum postulate and the recent development of atomic theory. Nature 121, 580–590 (1928).

Wootters, W. K. & Zurek, W. H. Complementarity in the double-slit experiment: Quantum nondeparability and quantitative statement of Bohr’s principle. Phys. Rev. D 19, 473–484 (1979).

Greenberger, D. M., Horne, M. A. & Zeilinger, A. Multiparticle interferometry and the superposition principle. Phys. Today 46(8), 22–29 (1993).

Jacobson, J., Gjörk, G., Chung, I. & Yamamato, Y. Photonic de Broglie waves. Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 4835–4838 (1995).

Edamatsu, K., Shimizu, R. & Itoh, T. Measurement of the photonic de Broglie wavelength of entangled photon pairs generated by parametric down-conversion. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 213601 (2002).

Walther, P. et al. Broglie wavelength of a non-local four-photon state. Nature 429, 158–161 (2004).

Giovannetti, V., Lloyd, S. & Maccone, L. Quantum-enhanced measurements: beating the standard quantum limit. Science 306, 1330–1336 (2004).

Leibfried, D. et al. Toward Heisenberg-limited spectroscopy with multiparticle entangled states. Science 304, 1476–1478 (2004).

Wang, X.-L. et al. 18-qubit entanglement with six photons’ three degree of freedom. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 260502 (2018).

Kok, P., Braunstein, S. L. & Dowling, J. P. Quantum lithography, entanglement, and Heisenberg-limited parameter estimation. J. Opt. B: Quantum Semiclass. Opt. 6, S811–S815 (2004).

Clerk, A. A. et al. Introiduction to quantum noise, measurement, and amplification. Rev. Mod. Phys. 82, 1155–1208 (2010).

Pezze, L. et al. Quantum metrology with nonclassical states of atomic ensemble. Rev. Mod. Phys. 90, 035005 (2018).

Degiorgio, V. Phase shift between the transmitted and the reflected optical fields of a semireflecting lossless mirror is π/2. Am. J. Phys. 48, 81–82 (1980).

Solano, E., de Matos Filho, R. L. & Zagury, N. Deterministic Bell states and measurement of the motional state of two trapped ions. Phys. Rev. A 59, R2539–R2543 (1999).

Kessler, T. et al. A sub-40-mHz-linewidth laser based on a silicon single-crystal optical cavity. Nat. Photon. 6, 687–692 (2012).

Mandel, L. Coherence and indistinguishability. Opt. Lett. 16, 1882–1883 (1991).

Pedrotti, F. L., Pedrotti, L. M. & Pedrotti, L. S. Introduction to Optics (Pearson Addison Wesley, London, 2007).

Bell, J. S. On the Einstein Podolsky Rosen paradox. Physics 1, 195 (1964).

Clauser, J. F., Horne, M. A., Shimony, A. & Holt, R. A. Proposed experiment to test local hidden-variable theories. Phys. Rev. Lett. 23, 880–884 (1969).

Rarity, J. G. & Tapster, P. R. Experimental violation of bell’s inequality based on phase and momentum. Phys. Rev. Lett. 64, 2495–2498 (1990).

Franson, J. D. Bell inequality for position and time. Phys. Rev. Lett. 62, 2205–2208 (1989).

Pérez, D. et al. Multipurpose silicon photonics signal processor core. Nat. Commun. 8, 636 (2017).

Zhang, H. et al. On-chip modulation for rotating sensing of gyroscope based on ring resonator coupled with Mzah-Zenhder interferometer. Sci. Rep. 6, 19024 (2016).

Salomon, Ch., Hils, D. & Hall, J. L. Laser stabilization at the millihertz level. J. Opt. Soc. Am. B 5, 1576–1587 (1988).

Ludlow, A. D., Boyd, M. M., Ye, J., Peik, E. & Schmidt, P. O. Optical atomic clock. Rev. Mod. Phys. 87, 637–701 (2015).

Grote, H. et al. First Long-term application of squeezed states of light in a gravitational-wave observatory. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 181101 (2013).

Acknowledegments

This work was supported by a GIST research institute (GRI) Grant funded by GIST in 2020.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.S.H. solely wrote the manuscript text and prepared all ideas, figures, calculations, and discussions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ham, B.S. Deterministic control of photonic de Broglie waves using coherence optics. Sci Rep 10, 12899 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-69950-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-69950-8

This article is cited by

-

Macroscopically entangled light fields

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Experimental demonstrations of unconditional security in a purely classical regime

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Macroscopic and deterministic quantum feature generation via phase basis quantization in a cascaded interferometric system

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Analysis of phase noise effects in a coupled Mach–Zehnder interferometer for a much stabilized free-space optical link

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Coherently controlled quantum features in a coupled interferometric scheme

Scientific Reports (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.