Abstract

The salivary glands actively concentrate plasma nitrate, leading to high salivary nitrate concentrations (5–8 mM) after a nitrate-rich vegetable meal. Nitrate is an ecological factor that can induce rapid changes in structure and function of polymicrobial communities, but the effects on the oral microbiota have not been clarified. To test this, saliva of 12 healthy donors was collected to grow in vitro biofilms with and without 6.5 mM nitrate. Samples were taken at 5 h (most nitrate reduced) and 9 h (all nitrate reduced) of biofilm formation for ammonium, lactate and pH measurements, as well as 16S rRNA gene Illumina sequencing. Nitrate did not affect biofilm growth significantly, but reduced lactate production, while increasing the observed ammonium production and pH (all p < 0.01). Significantly higher levels of the oral health-associated nitrate-reducing genera Neisseria (3.1 ×) and Rothia (2.9 ×) were detected in the nitrate condition already after 5 h (both p < 0.01), while several caries-associated genera (Streptococcus, Veillonella and Oribacterium) and halitosis- and periodontitis-associated genera (Porphyromonas, Fusobacterium, Leptotrichia, Prevotella, and Alloprevotella) were significantly reduced (p < 0.05 at 5 h and/or 9 h). In conclusion, the addition of nitrate to oral communities led to rapid modulation of microbiome composition and activity that could be beneficial for the host (i.e., increasing eubiosis or decreasing dysbiosis). Nitrate should thus be investigated as a potential prebiotic for oral health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The salivary glands actively concentrate plasma nitrate into the saliva, which leads to fasting levels of salivary nitrate in the 100–500 μM range (i.e., approximately 10 times higher than in plasma) (reviewed in REFS1,2). After a nitrate containing meal, this mechanism causes a further increase of salivary nitrate concentrations up to 5–8 mM2, which remain elevated many hours due to the long half-life circulation of nitrate3. The food groups that naturally contain most nitrate are vegetables and fruits, both generally associated with health benefits, lower disease prevalence and longevity4,5. Certain oral bacteria reduce nitrate (NO3−) mostly to nitrite (NO2−), but also further to more reactive nitrogen intermediates such as nitric oxide (NO) in a process called denitrification6.

Importantly, a significant amount of the produced nitrite is swallowed and taken up into the blood circulation of the host, where it is converted into nitric oxide—a signaling molecule involved in cardiovascular and metabolic regulation4,7. This is referred to as the nitrate-nitrite-nitric oxide pathway and provides an oral microbiome-dependent way of obtaining bioactive nitric oxide in addition to the classical NO synthases of the host1. Described systemic effects from nitrate supplementation include lowering of blood pressure, improved endothelial function, increased exercise performance, reversal of metabolic syndrome and anti-diabetic effects4. The importance of nitrate-reducing oral bacteria is reflected by the observation that blood pressure acutely increases in fasting individuals after using chlorhexidine mouthwash resulting from the loss of oral nitrate reduction7. Additionally, chlorhexidine mouthwash interferes with post-exercise hypotension8 and over-the-counter mouthwash usage correlated with pre-diabetes and diabetes development9.

Importantly, inside the oral cavity, salivary nitrate, nitrite and the nitrate reducing capacity of the oral microbiome have been proposed to be beneficial to prevent caries10,11,12. Additionally, two weeks of nitrate-rich lettuce juice consumption improved gingival health in a recent clinical study13. Finally, in other recent clinical intervention studies14,15, 1–4 weeks of high doses of nitrate in the form of concentrated beetroot juice increased the number of health-associated nitrate-reducing bacteria in saliva16. It is therefore important to determine experimentally if nitrate can be considered a dietary component associated with oral health.

While different studies have shed light on the molecular mechanisms involved in the systemic effects of nitrate reduction by the oral microbiota1,4,7,17, mechanisms leading to the apparent health-associated roles inside the oral cavity remain largely hypothetical. To unravel these mechanisms, the effect of nitrate on oral communities must be studied. Oral microorganism in saliva form biofilms on tooth surfaces (i.e., dental plaque) and the tongue (i.e., tongue coating)16,18. These biofilms are involved in the development of the most common oral diseases, including caries, periodontitis and halitosis.

It must be born in mind that nitric oxide has antimicrobial properties and planktonic cultures of certain oral species associated to periodontitis have shown to be sensitive to this highly oxidative compound19. It would therefore be crucial to determine if the reduction of nitrate affects the composition of oral communities by inhibiting the growth of disease-associated species, while increasing health-associated nitrate-reducing species. Furthermore, the capacity of oral bacteria to reduce nitrite to the alkali molecule ammonia, and to use lactic acid as a carbon source during denitrification could both prevent acidification, which is responsible for caries development6,12.

In relation to this, in a pioneering study, Koopman et al. (2016)20 applied 5 mM nitrate pulses of 6 min to 1–4 week old oral microcosms (i.e., complex, large in vitro oral biofilms) from two individuals, and each of them responded differently to nitrate. However, an effect on pH buffering was not detected and the number of participants was too low to conclude how the biofilm composition may be affected by nitrate.

In our current study, the effect of a single dose of nitrate on freshly sampled oral communities was tested in vitro. In short, saliva of 12 healthy donors was incubated in nutrient-rich medium with or without the physiologically relevant concentration of 6.5 mM nitrate in an impedance-based system (xCELLigence) that monitors real-time biofilm growth21,22. Samples were taken after 5 h, when most nitrate was reduced and some nitrite was produced, and at 9 h, when all nitrate and most nitrite were metabolized. Supernatant samples were taken for the measurements of nitrate, nitrite, ammonium, lactate and pH. The remaining biofilms were collected for protein and DNA quantification, as well as Illumina sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene. By this experimental protocol, we aimed to study the short-term effect of a single dose of nitrate on pH, oral biofilm growth and bacterial composition.

Materials and methods

Unstimulated saliva sampling

For this study, adults who reported to be systemically healthy were recruited as saliva donors at the FISABIO Institute (Valencia, Spain). Individuals were excluded if frank cavitation was detected at the moment of sampling (following the criteria of Rosier et al., 201723, which was assessed visually by an experienced dentist, or any history of periodontitis (following the criteria of Camelo-Castillo et al., 201524, as well as if they had used antibiotics or regularly used oral antiseptics in the previous month.

Twelve healthy donors were instructed to have a normal breakfast and abstain from oral hygiene before saliva collection in the morning. Five mL of unstimulated saliva were collected at least one hour after breakfast by drooling25 in a sterile tube in a quiet room. The saliva was used for in vitro growth and biofilm quantification. The procedure was repeated another time for biofilm sequencing and supernatant analysis.

To determine the effect of nitrate on acidification due to glucose fermentation, 9 healthy donors were asked to donate saliva under fasting conditions (abstaining from breakfast and oral hygiene) to avoid the presence of dietary-derived salivary nitrate.

The fresh unstimulated saliva was always directly used in the experiments or kept at 4 °C for < 1 h before usage. All donors gave informed consent prior to sample collection and the protocol was approved on 2016/05/23 by the Ethical Committee of DGSP-FISABIO (Valencian Health Authority) with the reference BIO2015-68711-R2. This study was carried out according to the relevant guidelines and regulations of the Declaration of Helsinki.

In vitro oral biofilm growth and impedance-based quantification

Unstimulated saliva of twelve donors was grown in ‘E-Plate 96’ 96-well plates in the xCELLigence system (ACEA Biosciences, San Diego, California, USA). Each E-Plate is coated with a golden layer at the bottom of the wells that is connected to microelectrodes, allowing the measurement of biofilm growth in real-time21,22,26,27. The impedance formed by biofilm adherence has been shown to be proportional to biofilm mass, which is provided by a corresponding Cell Index and expressed in arbitrary units28. Previous sequencing of biofilms grown under these circumstances show that bacterial composition is representative of different oral niches, depending on the sample type used for inoculation22.

BHI medium (Biolife, Deerfield, Illinois, USA) with an additional 0.05 mg/L haemin, 0.005 mg/L menadione and 0.2 mM vitamin K (all Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, Missouri, USA) was prepared of which 100 µL was added to each well for background impedance measurements. Additional 25 µL of 65 mM nitrate (NaNO3, Sigma-Aldrich) in water or just water was added to each well of the nitrate or control condition, respectively. Then, 125 µL freshly collected saliva was added, leading to a final concentration of 6.5 mM nitrate (within the 5–8 mM physiological range of saliva after a nitrate containing meal) in the nitrate condition. The E-Plate 96 was placed in the xCELLigence system inside an incubator at 37 °C. Every 10 min, a Cell Index measurement was taken. All experiments were performed without agitation and anaerobic conditions were favored by sealing the wells with adhesive aluminum foil (VWR, Radnor, Pennsylvania, USA), which previously allowed the growth of strictly anaerobic bacteria22. All conditions (control 5 h, control 9 h, nitrate 5 h, nitrate 9 h) were grown in duplicate.

For 0 h measurements, 1:1 medium and saliva mixtures were used. After 5 h and 9 h of growth, the supernatant was sampled and stored at − 20 °C until pH, nitrate, nitrite, ammonium and lactate measurements were performed in duplicate. A PBS washing step was then performed to remove unattached cells and, after this, the remaining cells were removed with a pipette and resuspended in 100 µL PBS. Biofilm duplicates were resuspended together in 200 µL PBS for storage at − 20 °C until DNA isolation for sequencing.

The washing step removed part of the (slightly attached) bacteria that had accumulated after 5 h or 9 h at the bottom of the well. Therefore, for protein and DNA quantification, the PBS washing step was not performed to quantify the entire microbial community that affected the physiological measurements in our in vitro system (e.g., pH, lactate and ammonium). After removing supernatant, the biofilms were resuspended in 75 µL PBS. It was observed that nitrate affects the impedance of the xCELLigence system and this effect depended on the saliva of the donor. Therefore, controls with microorganism-free filtered saliva were used to normalize the cell-index measurements. For this, the saliva was first filtered with a 5 µm filter and then with 0.1 µm filter.

Incubating saliva with nitrate and glucose

The unstimulated saliva of nine donors collected under fasting conditions was used to test the effect of different concentrations of nitrate on a pH drop caused by 0.2% of glucose after 5 h of incubation. For each donor, 187 µL of saliva and 22 µL of glucose (2% diluted in water) was added per well of a standard 96-well plate. Then, 11 µL of water without or with different concentrations of nitrate was added, leading to final concentrations of 0 mM, 0.5 mM, 1 mM, 1.5 mM, 2.5 mM, 3.5 mM, 4.5 mM, 5.5 mM, 6.5 mM ,7.5 mM and 8.5 mM of nitrate. The plate was sealed with adhesive aluminum foil and incubated during 5 h at 37 °C. After incubation, the samples were stored at − 20 °C until pH measurements.

Nitrate, nitrite, ammonium, lactate and pH measurements

For the nitrate, nitrite, ammonium, lactate and pH measurements, the RQflex 10 Reflectoquant (Merck Millipore, Burlington, Massachusetts, USA) reflectometer was used. This method is based on the intensity of reflected light by two reactive pads on test strips that change in color intensity based on the concentration of a specific substance29.

The test strips (Reflectoquant, Merck Millipore) for pH had a range from pH 4–9, the strips for nitrate a range of 3–90 mg/L, the strips for nitrite a range of 0.5–25 mg/L, the strips for ammonium a range of 5–20 mg/L, and the strips for lactate a range of 3–60 mg/L. Accuracy of all reflectometer methods was confirmed by the use of standard solutions (nitrate, nitrite, ammonium, all Merck Millipore; lactate, BioVision, Milpitas, California, USA) with known concentrations of the different compounds.

A method was used based on Hemke et al. (2009) and Ferrer et al. (2020)30,31. In short, undiluted supernatant was used for pH measurements and, for the rest of the measurements, 10 × or higher dilutions were made to obtain a concentration within the detection threshold of the test strips. Then, 15 µL of (diluted) supernatant was added to each of the two reactive patches on a strip, and excess liquid was removed by tipping the side of the strip on a tissue.

Before nitrate measurements, the diluted supernatants in which 0.5 mg/L or more nitrite was detected were treated with amidosulfuric acid (Sigma-Aldrich) based on the manufacturer's instructions. For this, 35 µL of diluted supernatant was mixed with 1.5 µL amidosulfuric acid solution (10%).

For ammonium measurements, aliquots were made of 50 µL diluted supernatant to which 10 µL of reagent 1 (ammonium 5–20 mg/L test strip kit, Reflectoquant, Merck Millipore) was added first and resuspended well. Then, 15 µL of a freshly made mixture of reagent 2 dissolved in 1.25 mL water was added and resuspended. This solution was then directly added to the strips and incubated according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Biofilms protein and DNA quantification

Biofilms grown for 5 h and 9 h were resuspended in 75 µL PBS of which 30 µL was used for protein quantification and the rest for DNA isolation. For protein quantification, the Bradford protein assay was applied, which is based on the colour change of the Coomassie Brilliant Blue dye (G-250) when bound to proteins. Duplicates of 15 µL of resuspended pellet were added to different wells of a standard 96-well plate. Then, 240 µL of Bradford Reagent (Sigma-Aldrich), containing G-250, was added and, after 5 min of incubation in the dark, the absorbance was measured with an Infinite F200 plate reader (TECAN, Männedorf, Switzerland) at 600 nm. Protein concentrations were determined using a calibration curve with known concentrations of BSA (range 0–1.5 mg/mL, Sigma-Aldrich) on each plate. For DNA quantification, DNA was extracted as described in the next section. Then, the DNA concentration was measured using the Qubit 1 × dsDNA HS Assay Kit and a Qubit 3 Fluorometer (both Thermo Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA), according to manufacturer’s instructions.

Biofilm composition determined by 16 rRNA sequencing

DNA extraction for sequencing

For DNA extraction, the biofilm duplicates (or salivary pellets from 250 µL saliva for inoculum sequencing) were resuspended in 100 µL PBS and disaggregated 30 s in a sonicator bath (model VCI-50, Raypa, Barcelona, Spain) at low ultrasound intensity. After this, DNA was isolated by MagNA Pure LC 2.0 Instrument (Roche Diagnostics, Risch-Rotkreuz, Switzerland), using the MagNA Pure LC DNA Isolation Kit III for Bacteria and Fungi (Roche Diagnostics) following the manufacturer’s instructions with an additional enzymatic lysis step: to a bacterial pellet in 100 µL PBS, 130 µL lysis buffer and 2.5 µL of enzyme mix, containing 20 mg/mL lysozyme (Thermomixer comfort, Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany), 5 mg/L lysostaphin (Sigma-Aldrich) and 0.625 mg/mL mutanolysin (Sigma-Aldrich), were added and incubated for 60 min at 37 °C. DNA was resuspended in 100 µL elution buffer and frozen at − 20 °C until further analysis. To determine the amount of DNA for sequencing, the Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA Assay Kit and a Qubit 3 Fluorometer (both Thermo Scientific) were used, according to manufacturer’s instructions.

16 rRNA sequencing

A pre-amplification step of the V1–V5 regions of the 16S rRNA gene was performed, following Dzidic et al. (2018)32. An Illumina amplicon library was then performed following the 16S rRNA gene Metagenomic Sequencing Library Preparation Illumina protocol (Part #15044223 Rev. A), targeting the 16S rRNA gene V3 and V4 regions, resulting in a single amplicon of 460 bp. Amplicons were sequenced on a MiSeq Sequencer according to manufacturer’s instructions (Illumina, San Diego, California, USA) using the 2 × 300 bp paired-ends protocol.

Taxonomic classification

The sequences were analyzed according to Boix-Amorós et al. (2016)33. In short, the reads were quality-filtered and end-trimmed in 10 bp windows with Prinseq. The PCR chimeras were removed with UCHIME according to Edgar et al. (2011)34. Given that taxonomic assignment accuracy decreases dramatically in reads shorter than 200 bp35, single reads were discarded and only joined reads were used to be taxonomically assigned at the genus level with the classifier of the Ribosomal Database Project36, using a confidence interval of 80%. Operational Taxonomic Unit (OTU) selection was performed using VSEARCH37 at a 97% of sequence identity. Given that taxonomic accuracy gets reduced at species level, especially in some genera with a highly similar 16S rRNA gene among species, only sequences > 400 bp were used for species-level classification38. We aligned each OTU centroid using BLAST at 97% of identity and 100% query coverage and retrieved only those species that agreed with the previous classification of the centroid at genus level provided by RDP classifier39.

Statistical analysis

We used overall R programming language for statistical computing40 to perform downstream analyses. Only those taxa with an abundance of > 0.001% in more than three samples in at least one condition were selected for the analyses. For multivariant analysis, an Adonis test (Permutational Multivariate Analysis of Variance Using Distance Matrices), provided by the Vegan library of R41, was used to compare groups. To visualize groups and their differences in a two-dimensional map, we computed constrained principal components via constrained correspondence analysis (CCA) which is also part of Vegan library41. For univariate analyses, paired non-parametric Wilcoxon tests (i.e., “wilcox.test” function of stats library of R40 were performed to test the differences in genera and all other parameters between groups. Correlations within and between genera and other parameters were determined with Spearman's rho, along with associated p-value using the “cor.test” function of the stats library of R40. Finally, to see if the observed taxonomic changes were supported by a standard compositional data analysis (CODA) technique, an ANCOM-II analysis was performed according to Kaul et al. (2017)42, which also controls the false discovery rate at a desired level of significance. For all taxonomic comparisons and correlations, only adjusted p-values were used.

Results

Effect of nitrate on biofilm growth

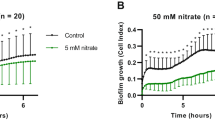

The addition of 6.5 mM nitrate (i.e., 403 mg/L) did not show significant changes in real-time impedance measurements of biofilm formation compared to the control condition (Fig. 1A). In agreement with this, total protein measurements of formed biofilms did not differ significantly between the different conditions (Fig. 1B). There was a positive correlation between DNA and protein of the communities (R = 0.62, p < 0.01). The amount of DNA, however, was 21% higher in the nitrate condition at 5 h (p < 0.01, Fig. 1C), suggesting that the number of cells could be higher under nitrate supplementation or that there is an increase in extracellular DNA. Additionally, 56% and 58% more DNA were detected in the control and nitrate conditions, respectively, at 9 h compared to 5 h (both p < 0.05).

Effect of nitrate on biofilm formation. Biofilms were grown with saliva as inoculum in a 6.5 mM nitrate condition (orange) and a control condition (blue). (A) Plot shows averages ± SE of biofilm mass, measured by Cell Index values, as indicated by impedance measurements, after normalization (norm.) with microorganisms-free filtered saliva. Measurements were taken every 10 min. Error bars are only shown at half an hour intervals for clarity. Sampling: samples were collected at 5 h and 9 h for different measurements (grey arrows). (B), (C) Protein and DNA quantification of the biofilms harvested at 5 h and 9 h. Bars represent averages of 12 donors with their corresponding standard deviations. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 according to a Wilcoxon test.

Changes in nitrate, nitrite, ammonium, lactate and pH during biofilm growth

Mixtures of saliva and BHI medium with or without 6.5 mM nitrate before growth (0 h) and the supernatants after 5 h and 9 h of growth were analyzed. At baseline (0 h), there were differences in the measured parameters between donors due to person-specific saliva properties (Fig. 2A–E; for measurements in individual donors, see Supplementary Spreadsheet).

Effect of nitrate supplementation on in vitro oral biofilm metabolism. Barplots show averages and standard deviations of measurements in supernatant samples from 12 donors under 6.5 mM nitrate (orange) and control (blue) conditions at different times of biofilm growth (0 h is the 1:1 mixture of saliva and medium, and 5 h and 9 h are supernatant measurements after in vitro growth). (A) Nitrate (mg/L), (B) nitrite (mg/L), (C) ammonium (mg/L), (D) lactate (mg/L) and (E) pH. ***p < 0.005, **p < 0.01, *p < 0.05, according to a Wilcoxon test.

In the condition with an additional 6.5 mM nitrate (i.e., 403 mg/L), most nitrate was used up after 5 h (Fig. 2A): in 7 individuals there was no nitrate detectable after 5 h, while for the other 5 donors, 76–85% of the nitrate had been reduced. In accordance with this, nitrite increased from an average of 1.64 mg/L at 0 h to 64.68 mg/L at 5 h. However, at 9 h the nitrite levels had dropped significantly, indicating further reduction to other compounds (Fig. 2B).

After 5 h, the mean of ammonium had increased 1.72 × in the control condition and 2.21 × in the nitrate condition compared to 0 h (both p < 0.005). Ammonium was significantly higher in the nitrate condition compared to the control conditions at 5 h (p < 0.01, Fig. 2C) and 9 h (p < 0.005).The mean of lactate increased notably after 5 h in both conditions compared to 0 h (4.74 × in the control condition and 3.40 × in the nitrate condition, both p < 0.005). After 9 h, the lactate had decreased in both conditions compared to 5 h (p < 0.005), indicating lactate was being metabolized. Importantly, lactate was significantly lower in the nitrate condition compared to the control condition at 5 h and 9 h (p < 0.005, Fig. 2D). There was a negative correlation between lactate and ammonium at 9 h that was more evident in the control condition (at 9 h, r = − 0.87, p < 0.005 in control and r = − 0.71, p < 0.05 in nitrate condition, Tables 1 and 2).

In accordance with a higher amount of ammonium production and lower amounts of lactate, pH was significantly higher in the nitrate condition at 5 h and 9 h (both, p < 0.005, Fig. 2E). In this regard, the pH dropped significantly after 5 h compared to 0 h in the control condition (p < 0.005), but not in the nitrate condition (p = 0.056). Interestingly, at 5 h, there was a negative correlation between pH and nitrite in the nitrate condition (r = − 0.82, p < 0.005, Table 2): individuals with 0 mg/L nitrite, possibly all used up, had the highest pH. Likewise, in the nitrate condition, ammonium correlated negatively with nitrite at 5 h (r = − 0.64, p < 0.05), indicating that part of the nitrite was further reduced to ammonia. In agreement with this, there was a negative correlation between the nitrate reduction capacity of communities (determined by the nitrate left after 5 h in the nitrate condition) and ammonium detected in both the nitrate and the control conditions (both r = − 0.717, p < 0.01, Table 2 and Supplementary Table 1). This suggests that communities with the best nitrate reduction capacity produced most ammonia (in the presence or absence of nitrate), indicating a possible link between the two processes.

The effect of different nitrate concentrations on acidification by sugar metabolism

To investigate if nitrate would have an effect on salivary acidification by sugar without the presence of culture medium, unstimulated saliva was incubated with 0.2% glucose and a concentration range of nitrate from 0.5–8.5 mM during 5 h (Fig. 3). The salivary pH before growth was 7.17 (SD 0.41). After 5 h of incubation with 0.2% glucose without nitrate, the pH dropped to pH 4.71 (SD 0.29, LQ 4.49, UQ 4.96). All nitrate concentrations from 1 mM to 8.5 mM resulted in a significantly higher pH after 5 h compared to 0 mM nitrate (p < 0.05 for 1 mM and 1.5 mM, p < 0.01 for higher concentrations up to 8.5 mM). Interestingly, 3.5 mM nitrate resulted in pH 4.92 (SD 0.36, LQ 4.75, UQ 5.2) and the pH levels did not further increase significantly when adding more nitrate.

Salivary acidification is inhibited by nitrate. Saliva of 9 donors was incubated for 5 h with 0.2% glucose and a given concentration of nitrate (0.5–8.5 mM), which is within the physiological range of human saliva. In this plot, averages (black dots) with standard deviations, upper quartiles (green line) and lower quartiles (red line) are shown. All the different concentrations of nitrate were compared with 0 mM nitrate and significance was marked with * for p < 0.05 and ** for p < 0.01 according to a Wilcoxon test.

Nitrate strongly affects biofilm composition

The addition of nitrate had a significant effect on the bacterial composition of in vitro oral communities, explaining a large proportion of data variability regardless of biofilm sampling time (Fig. 4). The control and nitrate conditions differed significantly at 5 h and 9 h (individual CCA and Adonis p-values ≤ 0.005, Supplementary Figure 1). The CCA p-value between the control condition at 5 h and 9 h was not significant, but the Adonis p-value was (< 0.05). The difference between the nitrate condition at 5 h and 9 h was significant (CCA and Adonis p-value < 0.05), indicating that oral communities can change rapidly (in a matter of a few hours) under certain conditions, especially in the presence of nitrate.

Effect of nitrate on oral biofilm composition at 5 h and 9 h of in vitro growth. Both Adonis and CCA p-values suggest statistically significant differences in bacterial composition on a genus-level between the control and nitrate conditions at 5 h and 9 h (for two-group comparisons, see Supplementary Figure 1). In this plot, the first constrained component clearly separates the two experimental conditions (control and nitrate), whereas the second one reflects variability due to time (5 h and 9 h), showing that both biofilm formation time and nitrate influence bacterial composition.

The relative abundances of individual donors at 5 h and 9 h were plotted as percentages in Fig. 5B and Supplementary Figure 2B, respectively (individual data can be found in the Supplementary Spreadsheet). Based on medians, in the control condition, the five most common genera after 5 h of biofilm growth were Streptococcus (50.17%), Veillonella (19.14%), Neisseria (6.62%), Haemophilus (6.16%) and Granulicatella (1.94%). In the nitrate condition, the most abundant genera after 5 h were Streptococcus (43.81%), Neisseria (20.27%), Veillonella (10.63%), Haemophilus (6.64%) and Gemella (2.17%). After 9 h, Streptococcus remained the dominant genus (38.94% and 32.78% in control and nitrate conditions, respectively) followed by Veillonella (28.85%), Haemophilus (8.75%), Neisseria (6.27%) and Porphyromonas (1.77%) in the control condition and by Neisseria (20.55%), Veillonella (19.53%), Haemophilus (8.22%) and Gemella (1.48%) in the nitrate condition. The saliva used as inoculum of 4 randomly selected donors was sequenced (Supplementary Figure 2A) and comparable dominant genera were found as in the in vitro biofilms (Fig. 5A and Supplementary Figure 2B): with a similar percentage of Streptococcus (43.88%) on the first place in the inoculum and then Veillonella (7.19%), Neisseria (6.97%), Gemella (6.44%) and Granulicatella (5.27%).

Bacterial composition in oral biofilms as determined by 16S rRNA sequencing. (A) Ring charts of the average relative abundance of genera in biofilms of 12 donors at 5 h and 9 h of growth. Above the ring charts, there is a zoom-in showing the low-abundance genera between Haemophilus (dark grey) and Steptococcus (blue). (B) Relative abundance of genera in biofilms of individual donors at 5 h. In this figure, the outer rings are the control condition (−) and the inner rings the condition with 6.5 mM nitrate (+). Genera at < 0.1% abundance are indicated as “Other” for clarity. The genera are sorted based on their maximum average abundance in one of the conditions from most to least abundant. Data for the inoculum and 9 h can be found in Supplementary Figure 2.

To study the effect of nitrate supplementation, significant changes in genera between the nitrate and the control conditions at 5 h or 9 h were analyzed (see Supplementary Spreadsheet for all p-values). The lower abundance of Veillonella (a bacterium that uses lactate as carbon source) in the nitrate condition compared to the control condition was significant at 5 h and 9 h (p < 0.05 and p < 0.01, respectively, Fig. 6) as well as the lower percentage of Streptococcus (a genus known to produce lactate) at 9 h (p < 0.05). The genus Prevotella at 5 h was lower in the control condition (1.51% compared to 0.78% in the nitrate condition, p < 0.05). No significant differences were observed between Haemophilus and Gemella in the two conditions. The dominant OTUs within each genera are listed in Supplementary Tables 2 and 3.

Changes in biofilm bacterial composition under nitrate conditions. Bar graphs show the log2 value of the ratio [average abundance nitrate condition]/[average abundance control condition] of 12 donors. Genera shown are those significantly different between the 6.5 mM nitrate and control conditions at 5 h or 9 h and, additionally, Treponema and Tannerella—two clinically relevant genera—were added. The genera that are higher in the nitrate condition are listed first and sorted by their highest average abundance in one of the conditions. After the vertical black stripe, the genera that are lower in the nitrate condition are listed, sorted by their highest average abundance in one of the conditions from highest to lowest (all taxa after unclass. Veillonellaceae had an average abundance of < 0.5% in all conditions). Red circles are placed before the genera of periodontitis-associated “red-complex” bacteria. unclass. = unclassified (only shown at family level); *adjusted p < 0.05 and **adjusted p < 0.01 between the control and nitrate conditions, according to a Wilcoxon test (Supplementary Spreadsheet).

The 3.1 × increase at 5 h and 3.3 × at 9 h of the median of Neisseria in the nitrate condition compared to the control condition were significant (both p < 0.01, Fig. 6). Identified Neisseria OTUs included N. flavescens, N. subflava, N. bacilliformis, and N. elongata. Rothia, another nitrate-reducing genera dominated by an OTU classified as R. aeria or R. dentocariosa, was at low abundance (i.e., median in all conditions 0.14%, range 0.01–1.7%), but the median was 2.9 × higher in the nitrate condition (0.35%) than in the control condition at 5 h (0.12%, p < 0.01). A third nitrate-reducing bacterium, Kingella, was present at low abundance but also at higher levels in the nitrate condition. However, the difference was not significant (p = 0.15).

Other genera significantly lower in the nitrate condition were periodontitis and/or halitosis-associated Porphyromonas (including the OTU P. endodontalis or oral taxon 285), Fusobacterium (including F. periodonticum and F. nucleatum), Leptotrichia (including the OTU L. wadei or oral taxon 417, and L. hongkongensis) and Avoprevotella (including A. rava and A. tannerae) at 5 h (p < 0.05), and the caries-associated Oribacterium (including O. parvum and O. sinus) at 9 h (p < 0.05). Decreases were also observed for the periodontitis-associated “red complex” bacteria Tannerella and Treponema (Fig. 6), but these differences were not significant using Wilcoxon adjusted p-values.

When using ANCOM-II adjusted p-values (Supplementary Figure 3 and Supplementary Spreadsheet), the significant changes in genera between the control and nitrate conditions were consistent (i.e., genera that differed significantly between the nitrate and control conditions at 5 h and/or 9 h using Wilcoxon adjusted p-values, still differed significantly at 5 h and/or 9 h using ANCOM-II adjusted p-values). However, several additional genera decreased significantly in the nitrate condition compared with the control condition when using ANCOM-II. These were Tannerella at 9 h, and Granulicatella, Atopobium, Actinomyces, Lachnoanaerobaculum and Dialister at 5 h.

In the nitrate condition, Veillonella and Actinomyces correlated negatively with pH at 9 h (r = − 0.77 and − 0.72, respectively, both p < 0.05, Supplementary Figure 4). In contrast, Neisseria correlated positively with pH at 9 h in the nitrate condition (r = 0.84, p < 0.01), as well as at 5 h in the control condition (r = 0.75, p < 0.05).

Discussion

The salivary glands contain electrogenic sialin 2NO3−/H+ transporters, which after a nitrate-containing meal increase salivary nitrate to millimolar levels, resulting in elevated nitrate concentrations over many hours43. The data presented in the current manuscript indicate that nitrate supplementation at the physiological levels found in saliva is able to prevent or reduce bacterial dysbiosis and stimulate eubiosis by elevating health-associated genera and reducing the levels of disease-associated bacteria. In addition, our work provides some of the mechanisms underlying the potential beneficial effect of nitrate for oral health, including lactate consumption or ammonia-mediated pH buffering (Fig. 7).

Overview of potential effects of nitrate inside the oral cavity. This graphical summary of the discussion is based on this study and current literature. Nitrate (NO3−) from food, such as vegetables (e.g., leafy greens, beetroots and carrots) and fruits, enters the blood stream and plasma nitrate is concentrated into saliva by sialin transporters in the salivary glands. There is also a direct effect of nitrate when the foods are chewed or pass through the mouth. Nitrate is reduced into nitrite (NO2−) and further to nitric oxide (NO) by denitrifying oral bacteria. Nitric oxide is an antimicrobial molecule that could limit the growth of certain species (e.g., periopathogenic species have been shown to be sensitive to NO) and thereby affecting the composition of oral biofilms. Additionally, at a pH of 5 and lower, acidic decomposition of nitrite to nitric oxide takes place (orange arrow), which could stimulate the antimicrobial effect when the pH drops due to sugar fermentation. Nitrite can also be reduced to ammonia (NH3) by the bacterial Dissimilatory Nitrate Reduction to Ammonium (DNRA) pathway, increasing the local pH. Additionally, nitrate-reducing species can use lactate as a carbon source, which further prevents a drop in pH. Other bacterial enzymes that lead to ammonia production are ureases using urea as a substrate and arginine deiminase system (ADS) enzymes using arginine. Denitrification is more energy efficient than sulfate reduction and, therefore, the presence of nitrate should limit hydrogen sulfide (H2S) production. In our study, we observed an increase of the health-associated genera Neisseria and Rothia, while caries-associated genera Streptococcus, Veillonella and Oribacterium decrease, as well as the anaerobic periodontal diseases- and halitosis-associated genera Porphyromonas, Fusobacterium, Leptotrichia, Prevotella, and Alloprevotella. It should be noted that these genera may also contain health-associated representatives. However, generally, the total abundance of these genera increases in the associated diseases. *assoc. associated genera, ADS arginine deiminase system.

It is surprising that nitrate metabolism in the oral cavity has scarcely been studied as a potential factor influencing biofilm composition and activity, as nitrate is an important ecological factor influencing the composition and functioning of microbial communities in natural environments6,44. There is evidence suggesting that nitrate reduction is also relevant for the oral cavity, where nitrate appears to lead to health-associated changes in the oral microbiota. For instance, nitrate metabolism has been associated with lower caries abundance11 and in a recent clinical study, gingival inflammation in patients with chronic gingivitis was significantly reduced after 14 days of nitrate intake in the form of lettuce juice13.

Our data show that less lactate and more ammonium was produced after 5 h and 9 h of in vitro oral biofilm growth in the presence of 6.5 mM nitrate, and, accordingly, the pH was higher than in the control condition without nitrate (all p < 0.01). Additionally, there was a strong negative correlation between lactate and ammonium produced after 9 h, which was more evident in the nitrate condition. This supports the hypotheses by Li et al. (2007)12 that alkali production and lactate consumption by nitrate-reducing communities limit a drop in pH when carbohydrates are fermented. In vivo this could potentially reduce the time that the dental tissue is under demineralizing pH45. In our study, we found that nitrate concentrations from 1 mM prevented salivary acidification due to glucose fermentation, while no additional pH buffering was observed for concentrations above 3.5 mM. Li et al.12 only used a nitrate concentration of 1.5 mM in modified saliva samples and also observed that nitrate prevented a drop in pH due to sugar fermentation by oral microorganisms under anaerobic conditions, but not under aerobic conditions. In addition, Burleigh et al. (2020)46 observed an increase in salivary pH after 7 days of nitrate-rich beetroot juice supplementation, which could be explained by the mechanisms detected in our in vitro study.

In our study, biofilm growth curves and protein levels were not significantly different between the control and the nitrate condition. Notably, biofilms grown with nitrate contained several times higher levels of Neisseria and Rothia, which are nitrate-reducing genera47,48, already after a short period of 5 h (p < 0.01) and Neisseria remained significantly higher after 9 h (p < 0.01). This included an increase of total abundance of Rothia mucilaginosa and Neisseria flavescens, which was also observed in vivo by Velmurugan et al. (2016)14 in saliva after 6 weeks of daily beetroot juice intake. Vanhatalo et al. (2018)15 showed that 10 days of daily beetroot intake increased Rothia and Neisseria, while decreasing Veillonella and Prevotella, in saliva, which is in accordance with our results in newly formed in vitro oral biofilms. Putting these results together, it appears that species of Rothia and Neisseria have a selective advantage in the presence of nitrate.

In the majority of recent sequencing studies, different Neisseria and Rothia species have been associated with disease-free individuals. For example, Rothia spp. and Neisseria spp. were more abundant in subgingival plaque of periodontally healthy individuals compared to patients with periodontitis49,50,51,52. Apart from relative abundance, also the prevalence of Rothia and Neisseria is higher in healthy subgingival plaque compared to periodontitis samples53.

Periodontitis is a chronic and destructive inflammation of the gingiva and can result from repeated or long-lasting episodes of gingivitis (i.e., reversible inflammation of the gingiva). In one study, the genus Neisseria correlated with anti-inflammatory mediators and was associated with a better recovery of the gingiva after experimental gingivitis54. In another study, Rothia aeria negatively correlated with inflammatory cytokines IL-17 and TNF-α55, whereas Rothia dentocariosa has been found to induce TNF-α production in a human cell line in vitro56. Given the high dynamic nature observed for many oral bacteria, nitrate-reducing isolates that show promising features as oral probiotics should be individually tested to confirm their systemic safety57.

Additionally, both Rothia58,59 and Neisseria58,60 species were more abundant in supragingival plaque of caries-free individuals compared to individuals with active caries. In a recent study, Rothia dentocariosa was also found to be more abundant on the tongue of halitosis-free individuals compared to halitosis patients61. In conclusion, Neisseria and Rothia are associated with oral disease-free individuals and an increase in these genera can be considered a positive change in the microbiota related to general oral health (i.e., eubiosis).

The DNA of biofilms in our study was 21% higher in the nitrate condition compared to the control condition after 5 h (p < 0.01), but not significantly different after 9 h. The small increase in DNA after 5 h could have resulted from a higher number of cells from, e.g., Rothia and Neisseria. Alternatively, the higher DNA amount could be derived from a larger production of extracellular DNA, which has previously been shown to affect biofilm integrity and adhesion62. Given that extracellular DNA could affect 16S rRNA sequencing results, in future experiments the samples could be treated with DNAse prior to DNA isolation to remove the effect of this extracellular DNA on bacterial composition assessment. Additionally, possible differences in biofilm properties due to extracellular DNA should be tested.

Regarding disease-related bacterial composition, we observed a decrease in Veillonella, Streptococcus and Oribacterium, which are genera associated with lactate, acidification and caries63,64,65, in the nitrate condition after 9 h (p < 0.05). Future studies performed with longer sequences should focus on species-level analyses, because even when a given genus is generally associated with disease (i.e., a consistent increase in disease is observed when compared with health in different studies), species66,67 and probably even strains within species could be associated with health.

Another important observation in our experiments was that periodontal-disease associated Porphyromonas, Fusobacterium, Prevotella, Leptotrichia and Alloprevotella were significantly lower in biofilms grown with nitrate after 5 h (p < 0.05). Porphyromonas, Fusobacterium, and Prevotella contain species of the classic ‘red and orange complexes’ identified by Socransky et al., which are strongly associated with periodontitis68. These include Fusobacterium periodonticum, Prevotella intermedia and Prevotella nigrescens that were also identified in our study. Similarly, Leptotrichia has a strong association with periodontitis69, while very recently it was confirmed that Alloprevotella is more abundant in disease as well67. Nitric oxide-releasing material and metal oxides have been shown to have antimicrobial activity against several periopathogenic species, including Porphyromonas gingivalis, Prevotella intermedia and Fusobacterium nucleatum70. Nitric oxide resulting from nitrate reduction could have killed slow-growing anaerobic bacteria in the inoculum, explaining their decrease after 5 h.

It is interesting to note that Porphyromonas, Fusobacterium, Leptotrichia and Prevotella are also associated with halitosis—bad breath resulting from microbial production of volatile sulfur compounds (VSCs)71. It must be kept in mind that nitrate is used as a biological agent to treat malodour from sewer networks by limiting microbial VSCs production resulting from sulfate reduction72. As long as more energy-efficient denitrification takes place, sulfate reduction is inhibited and this could also be the case in the oral cavity, where sulfate reduction is associated to halitosis73 (Fig. 7). The effect of nitrate supplementation on sulfate reduction and halitosis should be tested in future clinical studies.

The metabolism of nitrite and the production of ammonium in our study indicate the presence of Dissimilatory Nitrate Reduction to Ammonium (DNRA) activity by oral species. The observation that nitrite correlated negatively with ammonium and pH at 5 h (biofilms that metabolized all nitrite produced most ammonium and had the highest pH) further supports this. In the nitrate condition, the amount of ammonium after 9 h was 4.75 mM higher than in the control condition. Stoichiometrically, this could account for 73.1% of the 6.5 mM added nitrate, while (part of) the other 26.9% of nitrate may have been denitrified into nitric oxide and other nitrogenous products. It is unlikely that nitrate was used in assimilatory pathways as low concentrations of ammonium, which were present in all cultures, inhibit nitrate assimilation44,74. Interestingly, several environmental conditions, including pH and the protein:carbohydrate ratio75, direct the conversion of nitrate into ammonia or nitric oxide, and their role in regulating nitrate reduction in the oral cavity should be further investigated.

Arginine has received much attention as a prebiotic that is converted by certain oral microorganisms into ammonia, increasing the local pH and thereby having an anti-caries effect in vivo76,77. Urease activity by some oral bacteria has also been shown to buffer acidic pH by ammonia production and was shown to correlate with caries status78,79. We provide evidence that nitrate could have a similar effect and suggest that all three metabolic activities (i.e. arginine deaminase, urease and nitrate reduction) are considered when estimating the oral biofilm’s pH buffering capacity.

Nitrate: from disease-associated to neutral compound with health benefits

Nitrate has had a bad reputation for decades, because under certain conditions, its bacterial reduction product, nitrite, can react with other molecules and form potentially carcinogenic N-nitroso compounds (e.g., nitrosamine)80,81. This has been reported on processed meats, where nitrate salts are added as preservatives, resulting from bacterial and chemical reactions over time. However, humans obtain more than 80% of dietary nitrate from vegetables, which is a food group unequivocally associated with health benefits4, longevity and lower prevalence of diseases5, including cancer82. Anti-oxidants in fruits and vegetables prevent the formation of N-nitroso compounds from nitrite and stimulate the formation of nitric oxide83,84. In relation to this, different safety agencies stated that epidemiological studies do not suggest that nitrate intake from diet or drinking water is associated with increased cancer risk85 (reviewed by Lundberg et al., 20184. In contrast, evidence has accumulated that the oral microbiota-dependent increase of systemic nitric oxide resulting from dietary nitrate can have several beneficial cardio-metabolic effects4.

The current acceptable daily intake (ADI) of nitrate is 3.7 mg/kg of body weight (222 mg for an adult of 60 kg). In recent clinical studies focusing on cardiovascular effects, which observed an increase in Neisseria and Rothia in saliva, high daily doses of nitrate were given to individuals in the form of beetroot juice (i.e., 372–770 mg per day, which is 1.7–3.5 × the ADI) during periods of 1–4 weeks14,15,46. In our study, we show that a single dose of 101 µg nitrate to obtain 6.5 mM in a volume of 250 µL was enough to increase these nitrate-reducing genera in a short period of 5 h. To draw a parallel to the oral cavity, where volumes of around 0.5–1 mL of saliva are often found, topical doses far below the ADI would suffice to maintain a 6.5 mM concentration over time.

Conclusions

The results in this study showed that nitrate caused rapid structural and functional shifts in oral communities in vitro that would be of benefit to the human host. Based on our results, we conclude that nitrate could be an ecological factor stimulating health-associated oral genera, with the potential to decrease caries-, periodontitis- and halitosis- associated genera (Fig. 7). Additionally, we conclude that nitrate metabolism provides resilience to acidification resulting from sugar metabolism, by increasing lactate consumption and ammonia production, and future studies should test this possibility in vivo.

In biofilms grown with nitrate, Veillonella—a genus that uses lactate as carbon source—correlated negatively with pH and Neisseria positively. Due to the high in vivo prevalence of Neisseria and Rothia in different oral habitats, we argue that these genera could have essential roles in maintaining a healthy symbiotic relationship between the oral microbiota and the host by the reduction of salivary nitrate.

Taking into account our findings and other studies focusing on nitrate and oral health11,12,13,16, we propose that nitrate is a health-associated molecule in the oral cavity. We therefore suggest that nitrate could be used as a prebiotic (e.g., vegetable extracts or nitrate combined with anti-oxidants), and nitrate-containing vegetables tested in dietary interventions, in order to stimulate eubiosis or reduce dysbiosis in the oral cavity. Representatives of Neisseria, Rothia and other nitrate-reducing genera (e.g. Kingella) have traditionally been associated with oral health in many studies and we propose that this is, in part, due to their capacity to reduce nitrate. We therefore suggest that certain nitrate-reducing strains could be used as probiotics to stimulate the benefits of nitrate metabolism. We hope that, although preliminary, our in vitro data stimulate further research to test the potential effect of nitrate and nitrate-reducing bacteria on oral health in human subjects.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Hezel, M. P. & Weitzberg, E. The oral microbiome and nitric oxide homoeostasis. Oral Dis. 21, 7–16 (2015).

Lundberg, J. O. & Govoni, M. Inorganic nitrate is a possible source for systemic generation of nitric oxide. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 37, 395–400 (2004).

Pannala, A. S. et al. The effect of dietary nitrate on salivary, plasma, and urinary nitrate metabolism in humans. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 34, 576–584 (2003).

Lundberg, J. O., Carlström, M. & Weitzberg, E. Metabolic effects of dietary nitrate in health and disease. Cell Metab. 28, 9–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2018.06.007 (2018).

Wang, X. et al. Fruit and vegetable consumption and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer: systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. BMJ https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g4490 (2014).

Schreiber, F. et al. Denitrification in human dental plaque. BMC Biol. 8, 24 (2010).

Kapil, V. et al. Physiological role for nitrate-reducing oral bacteria in blood pressure control. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 55, 93–100 (2013).

Cutler, C. et al. Post-exercise hypotension and skeletal muscle oxygenation is regulated by nitrate-reducing activity of oral bacteria. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 143, 252 (2019).

Joshipura, K. J., Muñoz-Torres, F. J., Morou-Bermudez, E. & Patel, R. P. Over-the-counter mouthwash use and risk of pre-diabetes/diabetes. Nitric Oxide 71, 14–20 (2017).

Senthil Eagappan, A. R. et al. Evaluation of salivary nitric oxide level in children with early childhood caries. Dent. Res. J. (Isfahan) 13, 338–341 (2016).

Doel, J. J. et al. Protective effect of salivary nitrate and microbial nitrate reductase activity against caries. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 112, 424–428 (2004).

Li, H. et al. Salivary nitrate—an ecological factor in reducing oral acidity. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 22, 67–71 (2007).

Jockel-Schneider, Y. et al. Stimulation of the nitrate-nitrite-NO-metabolism by repeated lettuce juice consumption decreases gingival inflammation in periodontal recall patients: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J. Clin. Periodontol. 43, 603–608 (2016).

Velmurugan, S. et al. Dietary nitrate improves vascular function in patients with hypercholesterolemia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 103, 25–38 (2016).

Vanhatalo, A. et al. Nitrate-responsive oral microbiome modulates nitric oxide homeostasis and blood pressure in humans. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 124, 21–30 (2018).

Rosier, B. T., Marsh, P. D. & Mira, A. Resilience of the oral microbiota in health: mechanisms that prevent dysbiosis. J. Dent. Res. 97, 371–380 (2018).

Govoni, M., Jansson, E. A., Weitzberg, E. & Lundberg, J. O. The increase in plasma nitrite after a dietary nitrate load is markedly attenuated by an antibacterial mouthwash. Nitric Oxide 19, 333–337 (2008).

Kilian, M. et al. The oral microbiome—an update for oral healthcare professionals. Br. Dent. J. 221, 657–666 (2016).

Backlund, C. J., Sergesketter, A. R., Offenbacher, S. & Schoenfisch, M. H. Antibacterial efficacy of exogenous nitric oxide on periodontal pathogens. J. Dent. Res. 93, 1089–1094 (2014).

Koopman, J. E. et al. Nitrate and the origin of saliva influence composition and short chain fatty acid production of oral microcosms. Microb. Ecol. 72, 479–492 (2016).

Ferrer, M. D. et al. Effect of antibiotics on biofilm inhibition and induction measured by real-time cell analysis. J. Appl. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.1111/jam.13368 (2016).

Mira, A. et al. Development of an in vitro system to study oral biofilms in real time through impedance technology: validation and potential applications. J. Oral Microbiol. 11, 1609838. https://doi.org/10.1080/20002297.2019.1609838.eCollection2019 (2019).

Rosier, B. T. et al. Caries incidence in a healthy young adult population in relation to diet. JDR Clin. Trans. Res. 2, 142–150 (2017).

Camelo-Castillo, A. J. et al. Subgingival microbiota in health compared to periodontitis and the influence of smoking. Front. Microbiol. 6, 119 (2015).

Navazesh, M. & Christensen, C. M. A comparison of whole mouth resting and stimulated salivary measurement procedures. J. Dent. Res. 61, 1158–1162 (1982).

Junka, A. F. et al. Use of the real time xCelligence system for purposes of medical microbiology. Pol. J. Microbiol. 61, 191–197 (2012).

Ferrer, M. D., Lamarche, B. & Mira, M. Studying Bacterial Biofilms Using Cellular Impedance. xCELLigence® Real-Time Cell Analyzers (2017).

Gutiérrez, D., Hidalgo-Cantabrana, C., Rodríguez, A., García, P. & Ruas-Madiedo, P. Monitoring in real time the formation and removal of biofilms from clinical related pathogens using an impedance-based technology. PLoS ONE 11(10), e0163966 (2016).

Holden, N. M. & Scholefield, D. Paper test-strips for rapid determination of nitrate tracer. Commun. Soil Sci. Plant Anal. 26, 1885–1894 (1995).

Ferrer, M. D. et al. A pilot study to assess oral colonization and pH buffering by the probiotic Streptococcus dentisani under different dosing regimes. Odontology 108, 180–187 (2019).

Helmke, A. et al. The acidification of lipid film surfaces by non-thermal DBD at atmospheric pressure in air. New J. Phys. https://doi.org/10.1088/1367-2630/11/11/115025 (2009).

Dzidic, M. et al. Oral microbiota maturation during the first 7 years of life in relation to allergy development. Allergy 73, 2000–2011 (2018).

Boix-Amorós, A., Collado, M. C. & Mira, A. Relationship between milk microbiota, bacterial load, macronutrients and human cells during lactation. Front. Microbiol. 7, 492 (2016).

Edgar, R. C., Haas, B. J., Clemente, J. C., Quince, C. & Knight, R. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics 27, 2194–2200 (2011).

Claesson, M. J. et al. Comparison of two next-generation sequencing technologies for resolving highly complex microbiota composition using tandem variable 16S rRNA gene regions. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, e200 (2010).

Wang, Q., Garrity, G. M., Tiedje, J. M. & Cole, J. R. Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 5261–5267 (2007).

Rognes, T., Flouri, T., Nichols, B., Quince, C. & Mahé, F. VSEARCH: a versatile open source tool for metagenomics. PeerJ 4, e2584 (2016).

Camelo-Castillo, A. et al. Nasopharyngeal microbiota in children with invasive pneumococcal disease: identification of bacteria with potential disease-promoting and protective effects. Front. Microbiol. 10, 11 (2019).

Dzidic, M. et al. Oral microbiome development during childhood: an ecological succession influenced by postnatal factors and associated with tooth decay. ISME J. 12, 2292–2306 (2018).

R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. https://www.R-project.org/, https://www.R-project.org/ (2014).

41Oksanen, J., Blanchet, F.G., Friendly, M., Kindt, R., Legendre, P., McGlinn, D., Minchin, P.R., O'Hara, R.B., Simpson, G.L., Solymos, P., Stevens, M.H., Szoecs, E., Wagner, H. vegan: Community Ecology Package. R package version 2.4-2 https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=vegan (2017).

Kaul, A., Mandal, S., Davidov, O. & Peddada, S. D. Analysis of microbiome data in the presence of excess zeros. Front. Microbiol. 8, 2114 (2017).

Qu, X. M. et al. From nitrate to nitric oxide: the role of salivary glands and oral bacteria. J. Dent. Res. 95, 1452–1456 (2016).

Tiedje, J. M. Ecology of denitrification and dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium. Biol. Anaerob. Microorg. 717, 179–244 (1988).

Ten Cate, J. M. Novel anticaries and remineralizing agents: prospects for the future. J. Dent. Res. 91, 813–815 (2012).

Burleigh, M. et al. Dietary nitrate supplementation alters the oral microbiome but does not improve the vascular responses to an acute nitrate dose. Nitric Oxide 89, 54–63 (2019).

Doel, J. J., Benjamin, N., Hector, M. P., Rogers, M. & Allaker, R. P. Evaluation of bacterial nitrate reduction in the human oral cavity. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 113, 14–19 (2005).

Hyde, E. R. et al. Metagenomic analysis of nitrate-reducing bacteria in the oral cavity: implications for nitric oxide homeostasis. PLoS ONE 26, 3 (2014).

Abusleme, L. et al. The subgingival microbiome in health and periodontitis and its relationship with community biomass and inflammation. ISME J. 7, 1016–1025 (2013).

Griffen, A. L. et al. Distinct and complex bacterial profiles in human periodontitis and health revealed by 16S pyrosequencing. ISME J. 6, 1176–1185 (2012).

Kistler, J. O., Booth, V., Bradshaw, D. J. & Wade, W. G. Bacterial community development in experimental gingivitis. PLoS ONE 8, e71227 (2013).

Ikeda, E. et al. Japanese subgingival microbiota in health vs disease and their roles in predicted functions associated with periodontitis. Odontology https://doi.org/10.1007/s10266-019-00452-4 (2019).

Meuric, V. et al. Signature of microbial dysbiosis in periodontitis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 83, e00462-e517 (2017).

Joshi, V., Matthews, C., Aspiras, M., de Jager, M., Ward, M. & Kumar, P. Smoking decreases structural and functional resilience in the subgingival ecosystem. CONFIDENTIAL DATA (2014).

Corrêa, J. D. et al. Oral microbial dysbiosis linked to worsened periodontal condition in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Sci. Rep. 9(1), 8379. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-44674-6 (2019).

Kataoka, H. et al. Rothia dentocariosa induces TNF-alpha production in a TLR2-dependent manner. Pathog. Dis. 71, 65–68 (2014).

Binder, D., Zbinden, R., Widmer, U., Opravil, M. & Krause, M. Native and prosthetic valve endocarditis caused by Rothia dentocariosa: diagnostic and therapeutic considerations. Infection 25, 22–26 (1997).

Alcaraz, L. D. et al. Identifying a healthy oral microbiome through metagenomics. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 18, 54–57 (2012).

Belda-Ferre, P. et al. The oral metagenome in health and disease. ISME J. 6, 46–56 (2012).

Crielaard, W. et al. Exploring the oral microbiota of children at various developmental stages of their dentition in the relation to their oral health. BMC Med. Genomics 4, 22. https://doi.org/10.1186/1755-8794 (2011).

Seerangaiyan, K., van Winkelhoff, A. J., Harmsen, H. J. M., Rossen, J. W. A. & Winkel, E. G. The tongue microbiome in healthy subjects and patients with intra-oral halitosis. J Breath Res. 6, 3 (2017).

Jakubovics, N. S. & Burgess, J. G. Extracellular DNA in oral microbial biofilms. Microbes Infect. 17, 531–537 (2015).

Aas, J. A. et al. Bacteria of dental caries in primary and permanent teeth in children and young adults. J. Clin. Microbiol. 46, 1407–1417 (2008).

Rosier, B. T., de Jager, M., Zaura, E. & Krom, B. P. Historical and contemporary hypotheses on the development of oral diseases: are we there yet?. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 4, 92 (2014).

Zhou, J. et al. Influences of pH and iron concentration on the salivary microbiome in individual humans with and without caries. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 83, e02412-02416 (2017).

López-López, A., Camelo-Castillo, A. J., Ferrer García, M. D., Simon-Soro, A. & Mira, A. Health-associated niche inhabitants as oral probiotics: the case of Streptococcus dentisani. Front. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2017.00379 (2017).

Chen, C. et al. Oral microbiota of periodontal health and disease and their changes after nonsurgical periodontal therapy. ISME J. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41396-017-0037-1 (2018).

Socransky, S. S., Haffajee, A. D., Cugini, M. A., Smith, C. & Kent, R. L. Jr. Microbial complexes in subgingival plaque. J. Clin. Periodontol. 25, 134–144 (1998).

Costalonga, M. & Herzberg, M. C. The oral microbiome and the immunobiology of periodontal disease and caries. Immunol. Lett. 162, 22–38 (2014).

Vargas-Reus, M. A., Memarzadeh, K., Huang, J., Ren, G. G. & Allaker, R. P. Antimicrobial activity of nanoparticulate metal oxides against peri-implantitis pathogens. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 40, 135–139 (2012).

Seerangaiyan, K., Jüch, F. & Winkel, E. G. Tongue coating: its characteristics and role in intra-oral halitosis and general health-a review. J. Breath Res. 12, 034001 (2018).

Mathioudakis, V. L., Vaiopoulou, E. & Aivasidis, A. Addition of nitrate for odor control in sewer networks: laboratory and field experiments. Glob. NEST 8, 37–42 (2006).

Ren, W. et al. Tongue coating and the salivary microbial communities vary in children with halitosis. Sci. Rep. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep24481 (2016).

Huizenga, J. R., Vissink, A., Kuipers, E. J. & Gips, C. H. Helicobacter pylori and ammonia concentrations of whole, parotid and submandibular/sublingual saliva. Clin. Oral Investig. 3, 84–87 (1999).

Kraft, B. et al. Nitrogen cycling. The environmental controls that govern the end product of bacterial nitrate respiration. Science 345, 676–679 (2014).

Wolff, M. et al. In vivo effects of a new dentifrice containing 1.5% arginine and 1450 ppm fluoride on plaque metabolism. J. Clin. Dent. 24, A23–A31 (2013).

Koopman, J. E. et al. Changes in the oral ecosystem induced by the use of 8% arginine toothpaste. Arch Oral Biol. 73, 79–87 (2016).

Moncada, G. et al. Salivary urease and ADS enzymatic activity as endogenous protection against dental caries in children. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 39, 358–363 (2015).

Nascimento, M. M., Gordan, V. V., Garvan, C. W., Browngardt, C. M. & Burne, R. A. Correlations of oral bacterial arginine and urea catabolism with caries experience. Oral Microbiol. Immunol. 24, 89–95 (2009).

Skibsted, L. H. Nitric oxide and quality and safety of muscle based foods. Nitric Oxide 24, 176–183 (2011).

Sindelar, J. J. & Milkowski, A. L. Human safety controversies surrounding nitrate and nitrite in the diet. Nitric Oxide 26, 259–266 (2012).

Link, L. B. & Potter, J. D. Raw versus cooked vegetables and cancer risk. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 13, 1422–1435 (2004).

Ward, M. H. Too much of a good thing? Nitrate from nitrogen fertilizers and cancer. Rev. Environ. Health 24, 357–363 (2009).

Kobayashi, J., Ohtake, K. & Uchida, H. NO-rich diet for lifestyle-related diseases. Nutrients 7, 4911–4937 (2015).

Scientific Opinion of the Panel on Contaminants in the Food chain. Opinion of the Scientific Panel on Contaminants in the Food chain on a request from the European Commission to perform a scientific risk assessment on nitrate in vegetables. EFSA J. 698, 1–79 (2008).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Maria D. Ferrer, Dr. Arantxa López-López and Ms. Sandra Garcia-Esteban for fruitful discussions and help with laboratory work. We are also very grateful to the graphic designer Nicolas Fisher (nicolas.w.fisher@gmail.com), who did an excellent job in designing Fig. 7. Alex Mira is supported by a grant from the European Regional Development Fund and Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities with the reference RTI2018-102032-B-I00, as well as, a grant from the Carlos III Health Institute with the reference DTS16/00230. Bob T. Rosier is supported by a grant from the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities with the reference Bio2015-68711-R.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.T.R. and A.M. contributed to the design of work, and drafted and revised the manuscript. B.T.R. and E.B. did most experimental work. E.M.M.G. tested the effect of nitrate on acidification by sugar metabolism. B.T.R., E.B., E.M.M.G., A.A. and A.M. contributed to data the acquisition and analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

AM and BTR are co-inventors in a pending patent application owned by the FISABIO Institute, which protects the use of nitrate as a prebiotic. The rest of the authors declare to have no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rosier, B.T., Buetas, E., Moya-Gonzalvez, E.M. et al. Nitrate as a potential prebiotic for the oral microbiome. Sci Rep 10, 12895 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-69931-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-69931-x

This article is cited by

-

How probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics, and postbiotics prevent dental caries: an oral microbiota perspective

npj Biofilms and Microbiomes (2024)

-

Nitrate reduction capacity of the oral microbiota is impaired in periodontitis: potential implications for systemic nitric oxide availability

International Journal of Oral Science (2024)

-

The oral microbiome: diversity, biogeography and human health

Nature Reviews Microbiology (2024)

-

The oral microbiome in the pathophysiology of cardiovascular disease

Nature Reviews Cardiology (2023)

-

Nitrate and a nitrate-reducing Rothia aeria strain as potential prebiotic or synbiotic treatments for periodontitis

npj Biofilms and Microbiomes (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.