Abstract

Although many advances have been achieved to treat aggressive tumours, cancer remains a leading cause of death and a public health problem worldwide. Among the main approaches for the discovery of new bioactive agents, the prospect of microbial secondary metabolites represents an effective source for the development of drug leads. In this study, we investigated the actinobacterial diversity associated with an endemic Antarctic species, Deschampsia antarctica, by integrated culture-dependent and culture-independent methods and acknowledged this niche as a reservoir of bioactive strains for the production of antitumour compounds. The 16S rRNA-based analysis showed the predominance of the Actinomycetales order, a well-known group of bioactive metabolite producers belonging to the Actinobacteria phylum. Cultivation techniques were applied, and 72 psychrotolerant Actinobacteria strains belonging to the genera Actinoplanes, Arthrobacter, Kribbella, Mycobacterium, Nocardia, Pilimelia, Pseudarthrobacter, Rhodococcus, Streptacidiphilus, Streptomyces and Tsukamurella were identified. The secondary metabolites were screened, and 17 isolates were identified as promising antitumour compound producers. However, the bio-guided assay showed a pronounced antiproliferative activity for the crude extracts of Streptomyces sp. CMAA 1527 and Streptomyces sp. CMAA 1653. The TGI and LC50 values revealed the potential of these natural products to control the proliferation of breast (MCF-7), glioblastoma (U251), lung/non-small (NCI-H460) and kidney (786-0) human cancer cell lines. Cinerubin B and actinomycin V were the predominant compounds identified in Streptomyces sp. CMAA 1527 and Streptomyces sp. CMAA 1653, respectively. Our results suggest that the rhizosphere of D. antarctica represents a prominent reservoir of bioactive actinobacteria strains and reveals it as an important environment for potential antitumour agents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In general, microbial natural products have higher selectivity and bioactivity indices when compared to combinatorial chemistry libraries1,2. The search for bioactive molecules from microorganisms has received growing attention in recent decades3,4,5. Part of this is due to the specific action of microbial metabolites as substrates for many transport systems, which allows the release of compounds into intracellular sites6,7. However, despite the extensive search for microbial metabolites to address a great deal of clinical threat, the discovery rate of new and effective drug compounds has been declining every year, which is due, in part, to the use of traditional techniques of chemical isolation and the investigation of microorganisms in extensively studied environments3,8,9.

Thus, bioprospecting studies have advanced into auspicious ecological niches, which tend to favour the prevalence of exotic metabolisms and endemic species10,11. In this context, the Antarctic continent has been considered one of the most promising bioprospecting ecosystems and a valuable source to isolate new and diverse microorganisms due to its environmental peculiarities, such as extremely low temperatures and precipitation, high levels of UV radiation, ocean flooding, high salinity rates, and large unexplored areas12,13,14,15,16.

Although many organisms are adapted to the harshest environmental conditions of the Antarctic, the species Deschampsia antarctica Desv. (Poaceae) and Colobanthus quitensis (Kunth) Bartl. (Caryophyllaceae) have received more attention because they represent unique vascular plants in the whole Antarctic continent and play an important ecological role as a shelter for a plethora of microbes with wide metabolic capacities17,18. However, the reduced dispersion of D. antarctica Desv. in few Antarctic sites has attracted special interest in ecological and bioprospecting investigations17,19,20.

In this way, several studies have been carried out to characterize the microbiome associated with Antarctic hairgrass (D. antarctica), as well as to understand the adaptive mechanisms of this species to survive the harsh environmental conditions of Antarctica21,22,23. Even so, studies exploring the potential of this microbiome to access novel cultivable strains and bioactive compounds are still scarce.

Recently, Sivalingam and colleagues (2019)24 reported the prominence of Actinobacteria, especially species of Streptomyces, derived from extreme sources as an extraordinary reservoir of novel biosynthetic gene clusters with potential for developing anticancer drugs. Indeed, actinomycetes have been recognized as a prolific source of natural products with a myriad of bioactivities, including phytotoxic, antimicrobial, insecticidal and mainly antiproliferative and antitumour activities25,26,27,28. Compound classes belonging to the peptides, polyketides, macrolides, quinolones and others represent these bioactivities28,29,30,31,32. Accordingly, the isolation and identification of actinomycetes have become a fruitful area of research in recent years that has subsequently led to the identification of novel Actinomycete species that should be exploited to unveil possible biosynthetic pathways and discover new bioactive natural products12,33,34,35. Thus, the rhizosphere bacterial composition of Antarctic hairgrass (Fig. 1) was investigated by the 16S rRNA gene sequencing and the cultivable associated actinobacteria were evaluated as potential sources of antitumour compounds.

Satellite images (Google Earth Pro, 2019) and study sites. (A) Antarctic Continent; (B) Antarctic Peninsula; (C) South Shetland Islands; D-E–F) King George Island [sampling sites: Torre Meteoro Direito—TMD, Torre Meteoro Esquerdo—TME and Morro da Cruz—MDC (green, red and yellow location icon, respectively)]; (G) Deschampsia antarctica Desv.

Results

Bacterial community associated with Deschampsia antarctica rhizosphere

In this study, a total of 249.176 high-quality 16S rRNA reads were recovered after the QC filter step (Table S1—Supplementary Material). Sequences were assigned to 229.631 OTUs, and the rarefaction curves reached the plateau phases, confirming the adequate sequencing depth of the samples. The bacterial community structure revealed by the higher-ranking taxa classification was congruent among the different rhizosphere samples (Fig. 2).

The average taxonomic signatures of all samples from sites Morro da Cruz, Torre Meteoro Direito e Torre Meteoro Esquerdo (MDC, TMD and TME, respectively) showed that Actinobacteria (34%) was the most abundant phylum, followed by Chloroflexi (21%) and Proteobacteria (20%) (Fig. 2a). Members of the phyla Acidobacteria and Verrucomicrobia were detected at lower frequencies (< 5%). The ‘unclassified’ sequences contributed to 7% of the dataset, showing that the understanding of the plant-microbiome interaction is still limited and that the rhizosphere of D. antarctica may harbour unknown taxonomic groups to be further explored. A more detailed taxonomic analysis showed that the phylum Actinobacteria was mainly represented by members of the order Actinomycetales (86%), followed by Acidimicrobiales (8%) and Solirubrobacteriales (3%) (Fig. 2b).

Functional prediction of the bacterial communities

The predictive functional profile of the entire rhizosphere-associated bacterial community resulted in more than 6,500 protein-coding genes, which could be assigned to 329 KEGG Orthology functional categories (KOs). To determine a specific functional contribution, Actinobacteria-affiliated 16S rRNA reads were extracted and compared with the predictive functional traits of the total bacterial community. Principal component analysis (PCA) showed a clear separation between the predicted functional profiles of the total bacterial community and Actinobacteria groups (Figure S1—Supplementary Material). Nineteen KOs were significantly over-represented (p-value < 0.05) between the two datasets. The pathways carbohydrate metabolism, amino acid metabolism, metabolism of terpenoids and polyketides, xenobiotic biodegradation and metabolism, DNA replication and repair, membrane transporter, and biosynthesis of other secondary metabolites were significantly enriched (p < 0.05) in the Actinobacteria dataset when compared to the total bacterial community (Fig. 3).

Extended error bar plot showing the predicted KO-level 2 categories significantly different between total community and Actinobacteria members from Deschampsia antarctica Desv. rhizosphere (n = 9). Only P < 0.05 is displayed. (Kanehisa; Goto, 2000; Kanehisa et al., 2019; Kanehisa, 2019; Langille et al., 2013)38,39,40,41.

Isolating, culturing and identifying actinobacteria

A total of 72 actinomycetes were isolated with the media and procedures employed in this study. The isolates belonged to the genera Actinoplanes, Arthrobacter, Kribbella, Mycobacterium, Nocardia, Pilimelia, Pseudarthrobacter, Rhodococcus, Streptacidiphilus, Streptomyces and Tsukamurella from 6 families in the phylum Actinobacteria. Genomic analysis based on 16S rRNA sequences was used to select 30 isolates as representative strains of the accessed actinomycetes diversity. The nearest type strains, the percentage of identity and the GenBank access number are presented in Table S2—Supplementary Material. The strains are deposited in the Collection of Microorganisms of Agricultural and Environment Importance (CMAA)—Embrapa, Brazil (Fig. 4).

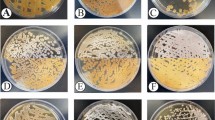

Screening for bioactive strains

First, all thirty isolated strains were evaluated against Pythium aphanidermatum CMAA 243T. Seventeen strains showed growth inhibition effects, as determined by the antagonism test (Figure S2 and Table S3—Supplementary Material), and these strains were selected for the antiproliferative assay against human tumour cell lines; glioma (U251), breast 174 (MCF-7) and lung/non-small cells (NCI-H460). Two strains, CMAA 1527 and CMAA 1653, exhibited potent activity, considering that Total Growth Inhibition (TGI) values lower than 6.25 µg/mL. Crude extracts of both CMAA 1527 and CMAA 1653 completely inhibited the growth of breast (MCF-7, TGI < 0.25 µg/mL, both extracts), glioblastoma (U251, TGI = 3.05 and < 0.25 µg/mL, respectively) and non-small lung (NCI-H460, TGI = 0.57 and 5.8 µg/mL, respectively) tumour cells (Fig. 5).

Phylogenetic analysis

According to the phylogenetic reconstruction based on the 16S rRNA gene similarity the bioactive actinobacterial strains were affiliated with the genus Streptomyces. The CMAA 1527 strain was closely related to Streptomyces aurantiacus NBRC 13017T, while CMAA 1653 was related to Streptomyces fildesensis DSM 41987T (Fig. 6), although they form a distinct phyletic branch towards the phylogenetic tree.

Phylogenetic tree based on the 16S rRNA gene sequences, obtained by Neighbor–Joining method analysis for the bioactive strains CMAA 1527 and CMAA 1653 and their closely related type strains—MEGA 7.042. Numbers at nodes indicate the level of bootstrap support based on 1,000 replications (only values > 50% are shown). Streptacidiphilus oryzae was used as outgroup for this study.

Bioassay-guided fractionation and structural identification of compounds

The crude extracts obtained from Streptomyces sp. CMAA 1527 and Streptomyces sp. CMAA 1653 showed high antiproliferative activity. Both extracts were analysed by LC–MS and presented different chemical profiles (Fig. 7).

The major peak in Streptomyces sp. CMAA 1527 crude extract was analysed by LC–MS at the retention time of 13.15 min and had mass spectra with m/z 826 (Fig. 7a). The extract was fractionated by semi-preparative HPLC, resulting in 4 grouped fractions (FR-1, FR-2, FR-3 and FR-4) that were subjected to a biological assay. Figure 5c and Table 1 shows the antiproliferative potential of fraction FR-3, the most bioactive fraction according to human cancer cell line panel. FR-3 was submitted to structural identification experiments, although other fractions showed lower biological activities (data not shown).

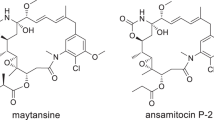

The chemical structure of FR-3 was confirmed by the analysis of the HRESIMS spectrum, and the molecular formula was determined to be C42H51NO16 as [M + H]+ was observed at m/z 826.3298 u, calculated for C42H52NO16+ (Figure S3—Supplementary Material). Cinerubin B was identified based on spectral data such as HRESIMS, 1H NMR, COSY, gHMBC, and gHMQC. The compound was isolated as a red amorphous powder that was soluble in methanol (MeOH) and trichloromethane (CHCl3) with UV absorption maxima at 490 nm. The 1H NMR spectrum of cinerubin B (Figure S4—Supplementary Material) showed signs of characteristic chemical shifts of anthracycline class; the signals of phenolic hydrogen were at δ 12.99 (s, 1H), δ 12.83 (s, 1H), and δ 12.28 (s, 1H). There were also signs of aromatic hydrogen at δ 7.75 (s, 1H) and δ 7.33 (d, J = 4.41 Hz, 2 H), as well as a broad doublet for a carbinolic hydrogen at δ 5.27 (dl, J = 2.50 Hz, 1 H). Other observed signals that are characteristic of this compound refer to three methoxyl group hydrogens at δ 3.71 (s, 3H), the hydrogen signals from an ethyl group at δ 1.76 (q, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H) and δ 1.09 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 3H), and the methyl hydrogen signals belonging to an N-dimethyl group at δ 2.16 (s, 6H). In addition, the presence of three anomeric hydrogens at δ 5.49 (sl, 1H), δ 5.12 (dl, J = 2.9 Hz, 1H), and δ 5.21 (dl, J = 2.9 Hz, 1H) indicated the presence of a trisaccharide moiety in the chemical structure of the compound. The 2D correlations from the HMBC and COSY spectra (Table S4—Supplementary Material) were used to assign all signals present in the cinerubin B structure (Fig. 8 and Figure S5—Supplementary Material).

In order to identify other anthracyclines the LC–MS/MS analysis using neutral loss methodology was performed. The chemical structure of the predominant compound produced by Streptomyces sp. CMAA 1527 (cinerubin B; m/z 826.3298 u) showed a neutral loss of 240 u, which refers to a charge-remote hydrogen rearrangement with consequent loss of disaccharide cinerulosyl-2-deoxyfucosyl to form the product ion m/z 586 as a base peak, which it was attributed to pyrromycin. This methodology allowed us to show the presence of other bioactive compounds in the crude extract (Figure S6—Supplementary Material) but with lower concentrations than cinerubin B since it was not possible to perform the isolation process. These compounds were identified as 1 or 11-hydroxysulfurmycin B (m/z 854), auramycin B (m/z 812) or N-desmethylcinerubine B (m/z 812) and 1-deoxycinerubin B (m/z 810) which have been attributed to the lower bioactivities detected at the others fractions (Figure S7, S8 and S9, respectively—Supplementary Material). Furthermore, it is noteworthy that these metabolites have isomeric structures; therefore, for unambiguous confirmation, it is necessary to perform NMR spectroscopic characterization for each of the isolated metabolites.

The analysis of the Streptomyces sp. CMAA 1653 crude extract revealed a predominant peak at 25.30 min corresponding to mass spectra m/z 1,269 (Fig. 7b and Figure S10—Supplementary Material). The HRESIMS/MS spectrum showed the main product ions of m/z 956, m/z 857, m/z 657, m/z 558, m/z 459, m/z 399, and m/z 300 (Figure S11—Supplementary Material). These ions provided abundant structural information, and their identification was performed. HRESIMS/MS data were identical to those previously reported in the literature44. As a result of the fractionation procedures, FR-5, FR-6 and FR-7 were recovered, within the FR-7 portion as the main bioactive fraction (Fig. 5d and Table 1). Thus, the compound present in the fraction FR-7 was identified as actinomycin V (C62H84N12O17) (Fig. 9). The other fractions obtained by semi-preparative HPLC did not show bioactivity in the experiments carried out in this study.

Discussion

The analysis of the rhizosphere microbiota in cold extreme habitats is crucial to understand the ecological roles and unlocking the biotechnological potential of these environments. Actinobacteria was also the dominant phylum in the rhizosphere of other D. antarctica retrieved from the maritime Antarctica region, as well as soils from cold and desert environments45,46,47,48. This prevalence may be explained by their spore-forming ability, UV radiation tolerance and other environmental adaptations that ensure survival in harsh conditions. Actinobacterial genera are known for their great potential to produce several bioactive substances47,49,50, although they also have the ability to degrade and use complex organic compounds and for their bioremediation of contaminated soils51. In fact, the predictive functional analysis using the Actinobacteria-derived 16S rRNA gene sequences showed enrichment of some functional categories related to carbohydrate metabolism, xenobiotic biodegradation and bioactive compound biosynthesis when compared with the total bacterial community. Vikram et al. (2016)52 also showed the genetic potential of Actinobacteria for C metabolism and membrane transport systems, which supports our PICRUSt functional predictions. The results obtained by 16S rRNA gene sequencing coupled to predictive functional analysis were useful to reveal diversified Actinobacteria pathways to produce biologically active metabolites. In doing so, we reported the presence of many pathways related to the biosynthesis of antibiotics such as streptomycin, novobiocin, phenylpropanoids, pyridine alkaloids, stilbenoids, neomycin, vancomycin, and tetracyclines, indicating a great bioactive potential of the bacterial community associated with D. antarctica (Table S5—Supplementary Material).

Despite advances in environmental sequencing (metagenomics) and single-cell genomics, the screening procedures of novel molecules remain largely related to the microorganisms culturing53. Thus, efforts to isolate new psychrotolerant strains were performed, resulting in a diverse collection of Actinobacteria revealed by the 16S rRNA gene sequencing. However, recent studies have found that discrepancies in terms of chemical and morphological features were possible in microorganisms belonging to same taxonomy, as determined for identical 16S rRNA gene sequences54. This finding was especially observed when studying bacteria from geographically distant origins or associated with different host species, in accordance to the ecovar concept55,56,57. Therefore, although the limitations of 16S rRNA gene have been widely recognized for screening of bioactive strains, we have assumed that the rhizosphere of D. antarctica could lead to high grade of specialism, with a lot of clonal populations. This fact was also observed in the 16S rRNA sequences of all isolated strains (data not shown), and supported by previous reports of Antarctic microbiota, which demonstrated that the type of habitat dramatically constrained the bacterial community composition45,58.

Although the Actinobacteria diversity has been underestimated through cultivation-dependent techniques, the isolation was able to access undiscovered species with the potential to produce novel bioactive compounds59,60,61. Some of them were not detected in microbiome analysis, possibly belonging to the rare community. Indeed, previous studies reported that cultivation techniques are still unable to access the real microbial diversity found in natural environments. The cultivation of recalcitrant microorganisms from extreme environments is difficult, especially the rhizosphere of Antarctic plants. However, the use of different culture media and growing conditions may be tested to improve the recovery of a major diversity of Actinobacteria members14,62. The low sequence identity registered in this study indicates the potential to identify novel species that require a polyphasic taxonomic approach for proper characterization and description. Based on phylogenetic, phenotypic and chemotaxonomic data, a new actinobacterial species isolated from D. antarctica was recently identified, named Rhodococcus psychrotolerans sp. nov12.

For current purposes, antiproliferative screening using P. aphanidermatum CMAA 243T as a model organism resulted in 17 bioactive strains. The bioassay was followed the protocol successfully applied to the primary screening against the Oomycota Pythium, which contain in its hyphal walls and cell membrane, proteins, lipids and sterols such as cholesterol, compounds which resemble cancer cells. The advantage of this method is the simplicity, low cost and practicality63. Among these strains, Streptomyces sp. CMAA 1527 and Streptomyces sp. CMAA 1653 stood out, showing a high antiproliferative index for human tumour cells. According to the phylogenetic reconstruction and 16S rRNA gene similarity, Streptomyces sp. CMAA 1527 was closely related to Streptomyces aurantiacus NBRC 13017T (99.37%), while Streptomyces sp. CMAA 1653 was related to Streptomyces fildesensis DSM 41987T (99.72%). Interestingly, Streptomyces fildesensis DSM 41987T was isolated from Antarctic soil and was recently presented as a prominent producer of antibiotic compounds64. Although both strains have been presented in the literature, they have not been listed as potential producers of antitumour compounds.

Cinerubin B is an important compound belonging to the anthracycline class. Anthracyclines are a special class of antibiotics widely used as antitumour agents, and the compounds daunomycin, doxorubicin, adriamycin, and aranciamycin anhydride have received great attention since their discovery65. The pronounced activity presented in the secondary metabolites of Streptomyces sp. CMAA 1653 can be clearly justified by the presence of actinomycin V (m/z 1,269.6170 u). The product ions at m/z 956, m/z 857, m/z 657, m/z 399 and m/z 300 corresponded to the loss of the Val-Pro-Sar-MeVal chain and were similar to those observed for actinomycin D44. Moreover, the product ion at m/z 558 indicated the presence of another Pro-Sar-MeVal residue in structure, as well as the product ion at m/z 459, which was characteristic of the core nucleus structure of actinomycins44,66. Actinomycins have been used as chemotherapeutic agents for the treatment of a variety of cancers and are produced by many Streptomyces strains24. They are a family of bicyclic chromopeptide lactones that attach two pentapeptide lactones of nonribosomal origin. Its use dates approximately 70 years ago, acting under several types of malignant human tumours, including nephroblastoma (Wilms’ tumour) and childhood rhabdomyosarcoma67,68,69, and has attracted attention for its potential to assist in the development growth of multi-drug resistance strains and inhibition of HIV-1 reverse transcriptase44,70,71.

Conclusions

This study reveals that the root-associated bacteria of Deschampsia antarctica Desv. from Antarctic ecosystems are a rich source of molecules with antitumour properties. The isolation methods employed in this study were able to retrieve Actinobacteria taxa that were not detected in microbiome analysis, showing that the combination of both strategies may be useful for recovering both rare and abundant members of the Actinobacteria communities for biotechnological exploration. The secondary metabolites of Streptomyces sp. CMAA 1527 and Streptomyces sp. CMAA 1653 showed valuable antiproliferative activities against human cancer cells and therefore can contribute significantly to the development of drugs of technological importance. Cinerubin B and actinomycin V were identified in the bioactive fractions of Streptomyces sp. CMAA 1527 and Streptomyces sp. CMAA 1653, respectively, but many other potential bioactive compounds can still be explored from Antarctic Actinobacteria. Based on these results, one of the two native Antarctic plants represents an attractive and unique model for the study of symbiosis and the discovery of antitumour lead compounds by the associated microbiome.

Methods

Sampling sites

Rhizospheric soil samples were collected (early summer Nov. 2014) at three different points (Morro da Cruz—62°05′04.3″ S/58°23′41.7″ W; Torre Meteoro Direito—62°05′10.4″ S/58°23′34.6″ W and Torre Meteoro Esquerdo—62°05′08.1″ S/58°23′36.6″ W) in Admiralty Bay, King George Island, South Shetland Islands, Antarctica. Deschampsia antarctica rhizospheric soil was obtained by removing plants from the soil (three plants for each collection point) and scraping 1–2 mm of soil adhering to the roots. Samples intended to actinobacteria isolation were kept at 4 °C and samples selected to genomic approach was stored at -20 °C until processed.

Bacterial 16S rRNA metabarcoding sequencing

DNA extractions of the rhizosphere samples were performed using the PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit (MoBio Laboratories—Carlsbad, CA, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. DNA yield and purity was evaluated by Qubit Fluorometric Quantification (Life Technologies—San Diego, CA, USA) and NanoDrop spectrophotometer (ThermoFischer Scientific—Waltham, MA, USA) (checking by the A260nm/280 nm and A260nm/230 nm ratios). The total DNA extracted from rhizosphere samples was ordered to the massive sequencing of the 16S rDNA gene for bacterial diversity analysis. The amplicons were obtained by the amplification of V6 16S rRNA hypervariable region72, using the primers 967F (5′-CAACGCGAAGAACCTTACC-3′) e 1193R (5′-CGTCRTCCCCRCCTTCC-3′)73, with an additional tag of five nucleotides added for each sample (https://vamps.mbl.edu/), according to Souza et al. (2017)74. The PCR products were pooled in equimolar ratio and purified by the SizeSelect EX E-Gel electrophoresis system (Life Technologies Corporation) for DNA size selection. The recovered fragments were further purified using the Agencourt AMPure XP kit (Beckman Coulter—Brea, CA, USA). Purified library product was quantified using the Qubit Fluorometric Quantification. The emulsion PCR procedure and sample enrichment were performed on the Ion OneTouch 2 system using the Ion Template PGM OT2 400 kit (Life Technologies Corporation). The V2 316 chip was used for sequencing as instructed in the Ion Torrent platform manual (Personal Genome Machine—PGM, Life Technologies Corporation).

Statistical and bioinformatic analyses

Raw data obtained from Ion Torrent sequencing were converted to FASTA file and submitted to quality control (QC) using the Galaxy platform75, with the following QC parameters: quality score = 25; barcode size = 5; quality window = 50, and maximum number of homopolymers = 6. Sequences with low quality and lengths < 180 bp were removed. After QC, the remaining high-quality reads were analyzed by the Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology (QIIME) version 1.9 software package36. Open reference operational taxonomic unit (OTU) were grouped at 97% sequence similarity OTU using UCLUST method and representative sequences of each OTU were taxonomically classified using the PyNAST alignment against GREENGENES (version gg_13_8) 16S reference database37,76. Chimeric sequences were detected and removed by the UCHIME algorithm76 before the construction of the OTU table. Afterward, all OTUs consisting of one single sequence (singletons), chloroplasts and non-bacterial sequences were removed before taxonomic classification.

The accurate predictive analysis was performed to infer the functional contribution of rhizosphere-associated Actinobacteria in comparison with the total community. Then, the PICRUSt tool41 was used to predict KEEG Orthology (KO) functional profiles of the bacterial community using the 16S rRNA dataset based on OTUs and reference genomes database38,39,40. For this, 16S reads affiliated to the Actinobacteria phylum were filtered after Greengenes database annotation. The final output of this workflow was quantified in terms of predicted function abundances per sample per OTU. Subsequently, the data were analyzed by the STAMP (Statistical Analysis of Metagenomic Profiles) software package v. 2.1.377 to evaluate biologically meaningful differences between rhizosphere-associated Actinobacteria and the total bacterial community. Statistical inferences were performed by G-test (w/Yates) + Fisher's, DP method: Asymptotic-CC 0.95 and p-value > 0.05 filter.

Isolation, culturing and identification of actinobacteria from rhizosphere

A pool of rhizosphere samples (0.25 g of each sample for three collected points; n = 9) was serially diluted (10–4, 10–5 and 10–6) in saline solution (NaCl 0.85%), and aliquots of 100 μL were plated on Starch Casein Agar (SCA)78, Humic Acid-Vitamin Agar (HVA)79 and Yeast Extract Malt Extract Agar (YEME)80. All media were supplemented with cycloheximide and nystatin (25 μg/mL) and incubated at 16 °C for 6 weeks. Isolates from the Deschampsia antarctica rhizosphere with the typical morphology of Actinobacteria colonies were taken from the selective isolation plates. The pure cultures obtained by repeated streaking were maintained on Glucose Yeast Extract Agar (GYEA) at 4 °C and as mixtures of mycelial fragments and spores in 20% glycerol (v/v) at − 80 °C.

Genomic DNA extraction, PCR amplification and sequencing methods were performed according to procedures adopted in Souza et al. (2017)34. The 16S rRNA consensus contigs were obtained using PhredPhrap/Consed81 and were aligned by ClustalW against nearest corresponding sequences using EzBioCloud82 and MEGA 7.042. Phylogenetic trees were inferred using the neighbour-joining83 tree-making algorithm drawn from the MEGA 7.0 package. Topologies of the resultant trees were evaluated by bootstrap analysis84 based upon 1,000 replicates.

Cultivation, extraction, and isolation of bioactive compounds

The metabolites of Streptomyces sp. CMAA 1527 and Streptomyces sp. CMAA 1653 were obtained by growing cultures in Potato Dextrose Broth on a rotating shaker (180 rpm, 16 °C) for 10 days. After growth, the mycelium was separated by centrifugation (7,000 rpm, 15 min, room temperature) followed by filtration (0.22 μm filter membrane). Each liquid culture medium was extracted with ethyl acetate (1:3 v/v), and the organic phase was evaporated to dryness under vacuum (Büchi Waterbath B-480). From each crude extract, at least three aliquots were separated, and two of them were subjected to antifungal (oomycete Phytium aphanidermatum CMAA 243T) and antiproliferative (human tumour and non-tumour cell lines) evaluations. Aliquots of each crude extract (650 mg) were fractionated by semipreparative HPLC on a Shimadzu LC system (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan) equipped with a CBM-20A controller, an LC-6AD pump, a DGU-20A5 degasser, and an SPD-20A UV–vis detector. The chromatographic separation was carried out using a C18 Zorbax Eclipse XDB column (250 × 9.4 mm, 5 μm; Agilent), and the mobile phase used was composed of 0.1% formic acid as system A and acetonitrile as system B. The gradient elution programme was 0—40 min from 30 to 100% of system B at a flow rate of 4 mL/min. The chromatograms were monitored using wavelengths at 320 and 500 nm.

Screening of bioactive strains

Antifungal activity

Bioactive strains were screened as described by Santos and Melo (2016)63, using Pythium. aphanidermatum CMAA 243T as a model organism. This bioassay was carried out as a primary screening for antitumour compounds from microorganisms. The antagonism assay was performed using sterile disc paper (0.5 cm diameter), crude extract solubilized in ethyl acetate (1 mg/mL) and potato dextrose agar medium. The plates were incubated at 28 °C for 24 h and evaluated according to the size of the inhibition zone, such as pronounced (+++), moderate (++), reduced (+) or absent (−).

Antiproliferative activity

The antiproliferative activity was investigated against a panel of human tumours [glioblastoma (U251), mamarian adenocarcinoma (MCF-7), ovarian multi-drug resistant adenocarcinoma (NCI/ADR-RES), large cell carcinoma of lung (NCI-H460), adenocarcinoma of kidney (786-0), ovarian adenocarcinoma (OVACAR-03), colon adenocarcinoma (HT-29) and chronic myeloid leukaemia (K-562)] and non-tumour (HaCat, immortalized keratinocytes) cell lines growing in complete medium [RPMI 1640 supplemented with 5% foetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin mixture (1,000 UI:1,000 μg/mL)] at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in a humidified atmosphere. Human tumour and the human non-tumoural cell lines were provided by the Frederick Cancer Research & Development Center (National Cancer Institute, Frederick, MD, USA), and Dr. Ricardo Della Colleta (University of Campinas).

The in vitro assay was performed as described by Monks et al. (1991)85. First, all extracts were screened against three tumour cell lines (U251, MCF-7 and NCI-H460). Then, the most promising extracts were evaluated against the complete panel. For both experiments, each extract was solubilized in dimethyl sulfoxide (100 mg/mL) followed by serial dilution in complete medium affording the final concentrations (0.25, 2.5, 25 and 250 μg/mL). Doxorubicin was used as a positive control at final concentrations of 0.025, 0.25, 2.5 and 25 μg/mL and was diluted following the same protocol.

Each cell line was grown in 96-well plates (100 μL cells/well) for 24 h and exposed for to the extracts, doxorubicin (positive control) or complete medium (negative control) for 48 h. Before (T0 plate) and after (T1 plates) sample addition, cells were fixed with 50% trichloroacetic acid dyed with sulforhodamine B 0.4% in acetic acid 0.1%, and colorimetric evaluation was recorded at 540 nm. The difference in absorbance between the untreated cells before (T0 plate) and after (T1 plates) sample addition represented 100% cell proliferation. Negative values represented a reduction in the cell population related to the T0 plate. The cell proliferation data were analysed using Origin 8.0 software (OriginLab Corporation) using sigmoidal regression to calculate the TGI and GI50 values (sample concentrations required total cell growth inhibition or to elicit 50% of cell death, respectively).

LC–MS analysis

The compounds present in the bioactive fractions were analysed using a Waters ACQUITY UPLC H-Class system coupled to the Xevo TQ-S tandem quadrupole (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA) mass spectrometer with a Z-spray source operating in the positive mode and to the diode arrangement detector (DAD) from 220 to 600 nm, according to Crevelin et al. (2014)31. The samples were solubilized in MeOH and injected (5 µL) into a Zorbax Eclipse XDB-C18 column (150 × 4.6 mm, 3.5 µm particle size—Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA); the mobile phase used for gradient elution consisted of 0.1% formic acid as system A and acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid as system B. The flow rate was 0.5 mL/min, and the gradient elution programme started with 30% B, increased to 90% B in the following 25 min, remained at 90% B for 5 min, and returned to the initial condition within the following 5 min. The source and operating parameters were optimized as follows: capillary voltage, 3.2 kV; cone voltage, 40 V; source offset, 60 V; Z-spray source temperature, 150 °C; desolvation temperature (N2), 350 °C; desolvation gas flow, 800 L/h (mass range from m/z 150 − 1,200).

High-resolution mass spectrometry analysis

The exact mass of the compounds present in the bioactive fractions was determined by high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRESIMS)31,86 on a mass spectrometer microTOFII‑ESI‑Q‑TOF (Bruker Daltonics, Billerica, MA, USA) employing an infusion pump (Kd Scientific, Holliston, MA, USA) at a flow rate of 100 µL/min. The voltage of the capillary was 3,500 V, and the voltage of the end plate was − 400 V in positive ionization mode. The source and operating parameters were optimized as follows: drying gas temperature (N2), 250 °C; a flow rate of 4 mL/min and a pressure of 0.4 bar. The tandem mass spectrometry experiments (MS/MS) with collision-induced dissociation were carried out using N2 as the collision gas on the selected precursor ion at collision energy values ranging from 10 to 50 eV. For internal calibration, a solution of sodium trifluoroacetic acid (Na-TFA) at a concentration of 1 mg/mL was used. Data acquisition and analysis were performed using Compass Data Analysis 4.1 software (Bruker Daltonics Corporation).

NMR analysis

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) measurements were carried out on a Bruker DRX 500 spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics Corporation) operating at 500 MHz for 1H and 125 MHz for 13C (δ in parts per million relative to Me4Si, J in Hertz). The isolated sample (5 mg) was dissolved in deuterated chloroform (CDCl3, Sigma-Aldrich) and analysed by 1D and 2D NMR using a Shigemi 5 mm NMR microtube, as described in Crevelin et al. (2013)86.

References

Stratton, C. F., Newman, D. J. & Tan, D. S. Cheminformatic comparison of approved drugs natural product versus synthetic origins. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 25, 4802–4807 (2015).

Kellenberger, E., Hofmann, A. & Quinn, R. J. Similar interactions of natural products with biosynthetic enzymes and therapeutic targets could explain why nature produces such a large proportion of existing drugs. Nat. Prod. Rep. 28, 1483–1492 (2011).

Harvey, A. L., Edrada-Ebel, R. & Quinn, R. J. The re-emergence of natural products for drug discovery in the genomics era. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 14, 111–129 (2015).

Tao, L. et al. Nature’s contribution to today’s pharmacopeia. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 979–980 (2014).

Li, J. W. H. & Vederas, J. C. Drug discovery and natural products: End of era or an endless frontier?. Biomeditsinskaya Khimiya 325, 148–160 (2009).

Wetzel, S., Bon, R. S., Kumar, K. & Waldmann, H. Biology-oriented synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 10800–10826 (2011).

Drewry, D. H. & Macarron, R. Enhancements of screening collections to address areas of unmet medical need: an industry perspective. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 14, 289–298 (2010).

Genilloud, O. Actinomycetes: still a source of novel antibiotics. Nat. Prod. Rep. 34, 1203–1232 (2017).

Monciardini, P., Iorio, M., Maffioli, S., Sosio, M. & Donadio, S. Discovering new bioactive molecules from microbial sources. Microb. Biotechnol. 7, 209–220 (2014).

Goodfellow, M., Nouioui, I., Sanderson, R., Xie, F. & Bull, A. T. Rare taxa and dark microbial matter: novel bioactive actinobacteria abound in Atacama Desert soils. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek Int. J. Gen. Mol. Microbiol. 111, 1315–1332 (2018).

Chu, P. L., Khoo, C. H. & Cheah, Y. K. Actinobacteria from Greenwich Island and Dee Island: isolation, diversity and distribution. Life Sci. Med. Biomed. 1, 1 (2017).

Silva, L. J. et al. Rhodococcus psychrotolerans sp. nov., isolated from rhizosphere of Deschampsia antarctica. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek Int J. Gen. Mol. Microbiol. 111, 629–636 (2018).

Wlostowski, A. N., Gooseff, M. N. & Adams, B. J. Soil moisture controls the thermal habitat of active layer soils in the mcmurdo dry valleys, Antarctica. J. Geophys. Res. Biogeosci. 123, 46–59 (2018).

Pulschen, A. A. et al. Isolation of uncultured bacteria from Antarctica using long incubation periods and low nutritional media. Front. Microbiol. 8, 1–12 (2017).

Hughes, K. A., Pertierra, L. R., Molina-Montenegro, M. A. & Convey, P. Biological invasions in terrestrial Antarctica: what is the current status and can we respond?. Biodivers. Conserv. 24, 1031–1055 (2015).

Iakovenko, N. S. et al. Antarctic bdelloid rotifers: diversity, endemism and evolution. Hydrobiologia 761, 5–43 (2015).

García-Echauri, S. A., Gidekel, M., Gutiérrez-Moraga, A., Santos, L. & de León-Rodríguez, A. Isolation and phylogenetic classification of culturable psychrophilic prokaryotes from the Collins glacier in the Antarctica. Folia Microbiol. (Praha) 56, 209–214 (2011).

Barrientos-Díaz, L., Gidekel, M. & Gutiérrez-Moraga, A. Characterization of rhizospheric bacteria isolated from Deschampsia antarctica Desv. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 24, 2289–2296 (2008).

Lee, J. et al. Transcriptome sequencing of the Antarctic vascular plant Deschampsia antarctica Desv. under abiotic stress. Planta 237, 823–836 (2013).

John, U. P. & Spangenberg, G. C. Xenogenomics: genomic bioprospecting in indigenous and exotic plants through EST discovery, cDNA microarray-based expression profiling and functional genomics. Comp. Funct. Genomics 6, 230–235 (2005).

Byun, M. Y. et al. Constitutive expression of DaCBF7, an Antarctic vascular plant Deschampsia antarctica CBF homolog, resulted in improved cold tolerance in transgenic rice plants. Plant Sci. 236, 61–74 (2015).

Xiong, F. S., Mueller, E. C. & Day, T. A. Photosynthetic and respiratory acclimation and growth response of Antarctic vascular plants to contrasting temperature regimes. Am. J. Bot. 87, 700–710 (2000).

Zuñiga, G. E., Alberdi, M. & Corcuera, L. J. Non-structural carbohydrates in Deschampsia antarctica Desv. from South Shetland Islands. Maritime Antarctic. Environ. Exp. Bot. 36, 393–399 (1996).

Sivalingam, P., Hong, K., Pote, J. & Prabakar, K. Extreme environment streptomyces: Potential sources for new antibacterial and anticancer drug leads? Int. J. Microbiol. 2019 (2019).

de Almeida, L. C. et al. Pradimicin-IRD exhibits antineoplastic effects by inducing DNA damage in colon cancer cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 168, 38–47 (2019).

Martinez, A. F. C., De Almeida, L. G., Moraes, L. A. B. & Cônsoli, F. L. Tapping the biotechnological potential of insect microbial symbionts: new insecticidal porphyrins. BMC Microbiol. 17, 1–10 (2017).

Bauermeister, A., Zucchi, T. D. & Moraes, L. A. B. Mass spectrometric approaches for the identification of anthracycline analogs produced by actinobacteria. J. Mass Spectrom. https://doi.org/10.1002/jms.3772 (2016).

Crevelin, E. J. et al. Isolation and characterization of phytotoxic compounds produced by streptomyces sp. AMC 23 from red mangrove (Rhizophora mangle). Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 171, 1602–1616 (2013).

Rodrigues, J. P. et al. Bioguided isolation, characterization and media optimization for production of Lysolipins by actinomycete as antimicrobial compound against Xanthomonas citri subsp. citri. Mol. Biol. Rep. 45, 2455–2467 (2018).

Bauermeister, A. et al. Pradimicin-IRD from Amycolatopsis sp. IRD-009 and its antimicrobial and cytotoxic activities. Nat. Prod. Res. 6419, 1–8 (2018).

Crevelin, E. J., Crotti, A. E. M., Zucchi, T. D., Melo, I. S. & Moraes, L. A. B. Dereplication of Streptomyces sp. AMC 23 polyether ionophore antibiotics by accurate-mass electrospray tandem mass spectrometry. J. Mass Spectrom. 49, 1117–1126 (2014).

Da Silva, L. J., Taketani, R. G., De Melo, I. S., Goodfellow, M. & Zucchi, T. D. Streptomyces araujoniae sp. nov.: An actinomycete isolated from a potato tubercle. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek Int. J. Gen. Mol. Microbiol. 103, 1235–1244 (2013).

Silva, L. J. et al. Streptomyces araujoniae produces a multiantibiotic complex with ionophoric properties to control botrytis cinerea. Phytopathology 104, 1298–1305 (2014).

Souza, D. T. et al. Saccharopolyspora spongiae sp. nov., a novel actinomycete isolated from the marine sponge Scopalina ruetzleri (Wiedenmayer, 1977). Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. (2017).

Silva, F. S. P. et al. Streptomyces atlanticus sp. nov, a novel actinomycete isolated from marine sponge Aplysina fulva (Pallas, 1766). Antonie van Leeuwenhoek Int. J. Gen. Mol. Microbiol. 109, 1467–1474 (2016).

Caporaso, J. G. et al. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nat. Methods 7, 1–12 (2011).

Caporaso, J. G. et al. PyNAST: a flexible tool for aligning sequences to a template alignment. Bioinformatics 26, 266–267 (2010).

Kanehisa, M. & Goto, S. Kegg: Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, 27–30 (2000).

Kanehisa, M., Sato, Y., Furumichi, M., Morishima, K. & Tanabe, M. New approach for understanding genome variations in KEGG. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D590–D595 (2019).

Kanehisa, M. Toward understanding the origin and evolution of cellular organisms. Protein Sci. 28, 1947–1951 (2019).

Langille, M. G. I. et al. Predictive functional profiling of microbial communities using 16S rRNA marker gene sequences. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 814–821 (2013).

Kumar, S., Stecher, G. & Tamura, K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33, 1870–1874 (2016).

Fouche, G. et al. In vitro anticancer screening of South African plants. J. Ethnopharmacol. 119, 455–461 (2008).

Imamichi, T. et al. A transcription inhibitor, actinomycin D, enhances HIV-1 replication through an interleukin-6-dependent pathway. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 40, 388–397 (2005).

Teixeira, L. C. R. S. et al. Bacterial diversity in rhizosphere soil from Antarctic vascular plants of Admiralty Bay, maritime Antarctica. ISME J. 4, 989–1001 (2010).

Mohammadipanah, F. & Wink, J. Actinobacteria from arid and desert habitats: diversity and biological activity. Front. Microbiol. 6, 1–10 (2016).

Undabarrena, A. et al. Exploring the diversity and antimicrobial potential of marine actinobacteria from the comau fjord in Northern Patagonia, Chile. Front. Microbiol. 7, 1–16 (2016).

Lacerda-Júnior, G. V. et al. Land use and seasonal effects on the soil microbiome of a Brazilian dry forest. Front. Microbiol. 10, 648 (2019).

Uzair, B. et al. Isolation, purification, structural elucidation and antimicrobial activities of kocumarin, a novel antibiotic isolated from actinobacterium Kocuria marina CMG S2 associated with the brown seaweed Pelvetia canaliculata. Microbiol. Res. 206, 186–197 (2018).

Girão, M. et al. Actinobacteria isolated from laminaria ochroleuca: a source of new bioactive compounds. Front. Microbiol. 10, 1–13 (2019).

Centurion, V. B. et al. Unveiling resistome profiles in the sediments of an Antarctic volcanic island. Environ. Pollut. 255, 113240 (2019).

Vikram, S. et al. Metagenomic analysis provides insights into functional capacity in a hyperarid desert soil niche community. Environ. Microbiol. 18, 1875–1888 (2016).

Prakash, O., Shouche, Y., Jangid, K. & Kostka, J. E. Microbial cultivation and the role of microbial resource centers in the omics era. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 97, 51–62 (2012).

Antony-Babu, S., Stach, J. E. M. & Goodfellow, M. Genetic and phenotypic evidence for Streptomyces griseus ecovars isolated from a beach and dune sand system. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek Int. J. Gen. Mol. Microbiol. 94, 63–74 (2008).

Sottorff, I. et al. Different secondary metabolite profiles of phylogenetically almost identical streptomyces griseus strains originating from geographically remote locations. Microorganisms 7 (2019).

Choudoir, M. J., Pepe-Ranney, C. & Buckley, D. H. Diversification of secondary metabolite biosynthetic gene clusters coincides with lineage divergence in Streptomyces. Antibiotics 7, 1–15 (2018).

Seipke, R. F. Strain-level diversity of secondary metabolism in Streptomyces albus. PLoS ONE 10, 1–14 (2015).

Malard, L. A. et al. Spatial variability of Antarctic surface snow bacterial communities. Front. Microbiol. 10, (2019).

Smith, J. J., Tow, L. A., Stafford, W., Cary, C. & Cowan, D. A. Bacterial diversity in three different antarctic cold desert mineral soils. Microb. Ecol. 51, 413–421 (2006).

Babalola, O. O. et al. Phylogenetic analysis of actinobacterial populations associated with Antarctic Dry Valley mineral soils. Environ. Microbiol. 11, 566–576 (2009).

Rego, A. et al. Actinobacteria and cyanobacteria diversity in terrestrial antarctic microenvironments evaluated by culture-dependent and independent methods. Front. Microbiol. 10, 1–19 (2019).

Chaudhary, D. K., Khulan, A. & Kim, J. Development of a novel cultivation technique for uncultured soil bacteria. Sci. Rep. 9, 1–11 (2019).

Santos, S. N. & Soares Melo, I. A rapid primary screening method for antitumor using the oomycete pythium aphanidermatum. Nat. Prod. Chem. Res. 04, 4–7 (2016).

Lavin, P. L., Yong, S. T., Wong, C. M. V. L. & De Stefano, M. Isolation and characterization of Antarctic psychrotroph Streptomyces sp. strain INACH3013. Antarct. Sci. 28, 433–442 (2016).

Li, W. et al. A new anthracycline from endophytic Streptomyces sp. YIM66403. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 68, 216–219 (2015).

Lin, A. et al. Off-target toxicity is a common mechanism of action of cancer drugs undergoing clinical trials. Sci. Transl. Med. 11 (2019).

Aldrink, J. H. et al. Update on Wilms tumor. J. Pediatr. Surg. 54, 390–397 (2019).

Hosoi, H. Current status of treatment for pediatric rhabdomyosarcoma in the USA and Japan. Pediatr. Int. 58, 81–87 (2016).

Green, D. M. The evolution of treatment for Wilms tumor. J. Pediatr. Surg. 48, 14–19 (2013).

Tietjen, I. et al. Inhibition of NF-KB-dependent HIV-1 replication by the marine natural product bengamide A. Antiviral Res. 152, 5–10 (2019).

Zhang, X., Ye, X., Chai, W., Lian, X. Y. & Zhang, Z. New metabolites and bioactive actinomycins from marine-derived Streptomyces sp. ZZ338. Mar. Drugs 14, 1–9 (2016).

Sogin, M. L. et al. Microbial diversity in the deep sea and the underexplored ‘“rare biosphere”’. PNAS 28, 12115 (2014).

Wang, Y. & Qian, P. Y. Conservative fragments in bacterial 16S rRNA genes and primer design for 16S ribosomal DNA amplicons in metagenomic studies. PLoS ONE 4, e7401 (2009).

Souza, D. T. et al. Analysis of bacterial composition in marine sponges reveals the influence of host phylogeny and environment. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 93, fiw204 (2017).

Goecks, J. et al. Galaxy: a comprehensive approach for supporting accessible, reproducible, and transparent computational research in the life sciences. Genome Biol. 11, R86 (2010).

Edgar, R. C., Haas, B. J., Clemente, J. C., Quince, C. & Knight, R. UCHIME improves sensitivity and speed of chimera detection. Bioinformatics 27, 2194–2200 (2011).

Parks, D. H. & Beiko, R. G. Measures of phylogenetic differentiation provide robust and complementary insights into microbial communities. ISME J. 7, 173–183 (2013).

Kuster, E. & Williams, S. Selection of media for isolation of Streptomyces. Nat. Publ. Gr. 4935, 928–929 (1964).

Hayakawa, M. & Nonomura, H. Humic acid-vitamin agar, a new medium for the selective isolation of soil actinomycetes. J. Ferment. Technol. 65, 501–509 (1987).

Shirling, E. & Gottlieb, D. Methods for characterization of Streptomyces species. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 16, 313–340 (1966).

Gordon, D., Abajian, C. & Green, P. Consed: A graphical tool for sequence finishing. Genome Res. 8, 195–202 (1998).

Yoon, S. H. et al. Introducing EzBioCloud: A taxonomically united database of 16S rRNA gene sequences and whole-genome assemblies. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 67, 1613–1617 (2017).

Saitou, N. & Nei, M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 4, 406–425 (1987).

Felsenstein, J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Soc. Study Evol. 39, 783–791 (1985).

Monks, A. et al. Feasibility of a high-flux anticancer drug screen using a diverse panel of cultured human tumor cell lines. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 83, 757–766 (1991).

Crevelin, E. J. et al. Isolation and characterization of phytotoxic compounds produced by Streptomyces sp. AMC 23 from red mangrove (Rhizophora mangle). Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 171, 1602–1616 (2013).

Acknowledgements

This study was made possible thanks to the laboratorial support of EMBRAPA Environment and financial support provided by CNPq (National Council for Scientific and Technological), FAPESP (São Paulo Research Foundation) and ProAntar (Brazilian Antarctic Program).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.J.S. carried out the rhizosphere collection. L.J.S., E.J.C., D.T.S. and A.L.T.G.R. performed the experiments. E.J.C. and G.L.V-J. tabulation, statistical analysis of data. L.J. S. E.J.C. and G.L.V-J. creation of tables and figures. The manuscript was written by L.J.S., E.J.C., D.T.S., G.L.V-J., V.M.O., A.L.T.G.R., L.H.R., L.A.B.M and I.S.M.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Silva, L.J., Crevelin, E.J., Souza, D.T. et al. Actinobacteria from Antarctica as a source for anticancer discovery. Sci Rep 10, 13870 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-69786-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-69786-2

This article is cited by

-

Cryosphere: a frozen home of microbes and a potential source for drug discovery

Archives of Microbiology (2024)

-

Induction of apoptosis and cell cycle arrest in colorectal cancer cells by novel anticancer metabolites of Streptomyces sp. 801

Cancer Cell International (2022)

-

Identification and antibacterial evaluation of endophytic actinobacteria from Luffa cylindrica

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Nocardia noduli sp. nov., a novel actinobacterium with biotechnological potential

Archives of Microbiology (2022)

-

Natural Products from the Poles: Structural Diversity and Biological Activities

Revista Brasileira de Farmacognosia (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.