Abstract

It is challenging to secure a cytopathologic diagnosis using minute amounts of tumor fluids and tissue fragments. Hence, we developed a rapid, accurate, low-cost method for detecting tumor cell-derived DNA from limited amounts of specimens and samples with a low tumor cellularity, to detect KRAS mutations in pancreatic ductal carcinomas (PDA) using digital PCR (dPCR). The core invention is based on the suspension of tumor samples in pure water, which causes an osmotic burst; the crude suspension could be directly subjected to emulsion PCR in the platform. We examined the feasibility of this process using needle aspirates from surgically resected pancreatic tumor specimens (n = 12). We successfully amplified and detected mutant KRAS in 11 of 12 tumor samples harboring the mutation; the positive mutation frequency was as low as 0.8%. We used residual specimens from fine-needle aspiration/biopsy and needle flush processes (n = 10) for method validation. In 9 of 10 oncogenic KRAS pancreatic tumor samples, the "water-burst" method resulted in a positive mutation call. We describe a dPCR-based, super-sensitive screening protocol for determining KRAS mutation availability using tiny needle aspirates from PDAs processed using simple steps. This method might enable pathologists to secure a more accurate, minimally invasive diagnosis using minute tissue fragments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

It is challenging to acquire histological evidence regarding solid tumors non-invasively; this hamper clinical management decisions that need to be made at appropriate time points. Fine-needle aspiration (FNA) is a standard procedure for collecting tumor tissues; however, there are cases where inadequate sampling resulted in false negative results1. This technical issue might be highlighted when tumors, including pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas (PDAs), which have a low tumor cell content, are targeted. Because of the invasiveness of needle-assisted cytology and biopsy as well as the potential for tumor cell dissemination, albeit at a low incidence, the frequent repetition of the procedure is not generally recommended2,3.

The assessment of the tumor grade and histological type is an essential task for pathologists; however, there are possibilities of inter-pathologist diagnostic disagreement4. Information regarding the expression levels of specific tumorigenesis-associated proteins in routine clinical practice enables pathologists to reach a consensus on the matter5. Limited amounts of specimens can also be an obstacle for performing additional molecular analysis, which emphasizes the necessity of alternative tools that provide evidence regarding malignant tumors6.

A robust solution might involve the detection of frequently mutated genes in a specific type of cancer7. For instance, in human PDAs, the KRAS gene is ubiquitously mutated, and in over 90–95% of patients, lesions emerged because of oncogenic events at the earliest periods of the tumorigenesis process8. Another initiating driver mutation in KRAS has been reported in colorectal (40%) and lung adenocarcinomas (15–20%). Mutations in other types of tumors, including BRAF mutations in melanomas (50–90%) and papillary thyroid carcinomas (50%), EGFR mutations in lung cancer, and PIK3CA mutations in colorectal and breast cancer might be used as genetic markers for the early identification of malignant tumors9,10,11,12.

Recent technological advances in genetics such as sequencing and PCR-based genetic analysis might allow the super-sensitive and absolute quantification of very low levels of mutant alleles, even in a small yield of tumor samples with shallow cellular content13. Here, we sought to further develop a new digital PCR (dPCR) protocol using tissues collected from pancreatic tumors by FNA, which allows for the detection of genetic mutations in small amounts of specimens. In pre-clinical settings, by obtaining tumor specimens right after resection, a high accuracy of detection of tumor cell-derived DNA via dPCR was achieved. By eliminating the genomic DNA purification process, the sample could be processed in a simple and rapid manner and subsequent analysis could be conducted; this may support the routine clinical diagnosis.

Results

Development of a method to detect the minimal copy number of tumor-derived mutant KRAS

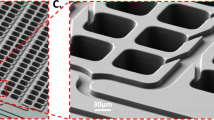

We investigated a method for detecting mutations in tiny tissue samples using absolute quantification via dPCR. To prepare input DNA from the samples, we first tested two methods, to avoid losses during the nuclear purification step. In the first method, cells/tissues were encapsulated using the droplet generator, and the PCR reaction was then directly performed. We performed serial dilution using two different cell lines, i.e. MIA PaCa-2 (homozygous KRAS G12C) and NB1RGB (wild-type KRAS). The ratios of mutants to wild-type genes in cell mixtures were 20:4,000, 100:4,000, 500:4,000, and 1,000:4,000. The cells suspended in 4 µL of PBS were directly enclosed within emulsion drops (Fig. 1A), using the QX200 system, and then used for the dPCR mutation detection assay. As shown in Fig. 1C, the frequency of detection of mutations after the capture of the enclosed cells was modest (12.9% in KRAS mutant cells or 2.9% in wild-type KRAS cells, on average).

Experimental results using cell lines to improve the dPCR method for the highly sensitive mutation analysis of simple prepared samples. (A) Encapsulated cells in dPCR droplets. Cells were collected, resuspended in dPCR reaction solution, and mixed with droplet generation oil using the QX200 droplet generator. Scale bars; 200 μm. (B) Cells were burst using pure water. Cells were collected and resuspended in nuclease-free water, which caused an osmotic burst of cells, and genomic DNA was released into the water. The “crude” solution, including gDNA, was used as the dPCR template. Scale bars; 500 μm. (C) The DPCR assay was performed using the two novel DNA preparation methods, without a purification step. KRAS wild-type (Fibroblast; NB1RGB) and KRAS G12C (PDA; MIA PaCa-2) cells were mixed with several dilution series (left panel). The wild-type or G12C mutation in KRAS was detected using the QX200 droplet reader, as compared to the conventional DNA preparation method using commercial purification kits (see details in “Methods”). The KRAS copy number of wild-type or G12C measured by QuantaSoft software (right panel).

We, therefore, examined the alternative method, where cells were collected and resuspended in nuclease-free water, which caused an osmotic burst of collected cells; this could cause genomic DNA to be released into the liquid fraction (Fig. 1B). The “crude” DNA was then directly utilized as the dPCR template without performing the DNA purification step (around 30 min); hence, throughout the assay, we could determine the KRAS mutation status in fresh tumor samples within 2.5 h (a few minutes of preparation of tumor-derived DNA before processing dPCR). The dPCR reaction proceeded successfully even with impure DNA, and the detection of the KRAS copy number was comparable to that for the sample prepared through conventional DNA purification (Fig. 1C). These results suggested that the “water-burst” method could be used to perform both timesaving preparation steps and achieve high-efficiency detection of small numbers of DNA copies.

Mutation detection analysis using fresh needle-aspirated tissues from resected pancreatic neoplasia

Next, we examined the feasibility of detecting KRAS mutants using a tiny amount of resected tumor tissue. Twelve patients with pancreatic tumors were enrolled, and the needle aspirates from the tumor and the non-tumor areas of the resected specimens were analyzed. The aspirates were suspended in nucleus-free water following storage and spin-down. In the dPCR assay, KRAS G12/G13 mutations were found in the PDA from 10 patients, including IPMN-associated pancreatic cancers; 1 PDA patient exhibited mutant KRAS Q61H. In contrast, no KRAS mutation was detected in tumors in a patient with a pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor (Table 1). Multiple KRAS mutations were found in the tumor obtained from one patient with IPMN-associated carcinoma.

Using the “water-burst” method, we successfully detected the KRAS G12/G13 mutations in the fresh needle aspirates from 10 PDAs with corresponding mutations. Besides, the KRAS Q61 mutation was found in 1 sample from a patient exhibiting KRAS Q61H mutation, while the number of KRAS G12/G13 mutations was below the cut-off value (Table 1, Supplementary Figure). We found a 100% concordance in KRAS mutations in a small tumor cohort including a sample with wild-type KRAS. The lowest frequency in the mutation to wild-type in these patients was 0.82% (mutation allele frequency in the primary tumor lesion was 12.8%; Table1).

Detection of KRAS mutations via dPCR using residual tissues of endoscopic biopsy samples

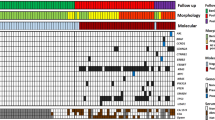

We attempted to validate the capture of dPCR-based driver mutations via the “water-burst” method using a residual piece of tumor tissue in the FNA needle. After submitting pancreatic tumor biopsy specimens to the pathology laboratory, minimal amounts of the remaining samples were collected to test the “water-burst” method, by scratching the residual tissues from Petri dishes and flushing the needle with the stabilizing solution (Fig. 2A). The fluid was preserved, shipped, and centrifuged before genetic analysis. Then, the pellets suspended in water and the supernatants were analyzed via the dPCR assay, which targeted KRAS mutations. In 9 of 10 patients, we found KRAS mutations in residual tissues (G12/G13 mutants in 8 patients, Q61 mutant in 1 patient) obtained after FNA. In 7 specimens of needle-rinsed fluids, we detected G12/G13 mutations in 6 patients, and Q61 mutation in 1 patient (Table 2, Fig. 2B). In patient 7, who was diagnosed with a pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma exhibiting no KRAS mutations, the level of the KRAS G12/G13 variant was found to be approximately similar to the detection limit of the screening kit (0.2%). In contrast, the mutation allele frequency in other samples with mutant KRAS was over 10%. Either the residual tissue or needle flush part of the FNA samples was also analyzed using dPCR assay following DNA purification (Table 2). A strong correlation was observed between amplified KRAS copy numbers and the amount of template DNA (Supplementary Table 2 and Supplementary Fig. 2). The “water-burst” assay using pellets from FNA residual tissue showed a KRAS mutant allele frequency equivalent to that of purified DNA except for patient 2, whereas the supernatants required DNA purification.

KRAS mutation analysis using FNA residual tissues via the “water-burst” sample preparation method. (A) Workflow for sample collection and DNA preparation. After submitting patient specimens obtained via FNA for cytopathological diagnosis, residual specimens and the needle washing solution were collected, centrifuged, and separated into a pellet and supernatant. DNA was prepared by the “water-burst” method, in which the precipitate was centrifuged and suspended in water, and dPCR analysis was then performed. The supernatant was directly subjected to the dPCR reaction. These methods do not require DNA purification, and it takes about 2.5 h to obtain genetic information after the collection of a sample. Purified DNA was also subjected to the assay as control (see Table 2). (B) DPCR plot of the KRAS G12/G13 mutation assay in the collected tissues were resuspended using water (left large panels). The plot graph shows the pattern of detection of KRAS tissues obtained via centrifugation from FNA residual tissues or needle rinsed fluids. The threshold (solid pink line) was manually set to extend to an amplitude of 2,000 or 1,000 (FAM mutant or HEX wild-type probe) above the maximum background intensity value. The asterisk indicates the results for the KRAS Q61 mutation assay for patient 9 (right small panels; see Table 2).

To confirm the fact that the KRAS mutations identified using this method originated from the tumor, pathological specimens from FFPE blocks were genotyped via targeted amplicon sequencing. In all 9 samples in which mutant KRAS was detected by the “water-burst” method, the KRAS mutation was pathologically proven to be present in the PDA tissue. In one patient with a KRAS G12D tumor, we failed to detect mutations during the FNA-needle flush process, while we could identify the mutation using DNA that was purified and concentrated from the supernatant and water-bursting of the residual tissue in FNA-needles (Table 2; patient 8). Another patient with an absent mutation calling in KRAS, as observed by the “water-burst” dPCR assay, was pathologically diagnosed as having a pancreatic acinar cell carcinoma with no KRAS mutations (patient 7). Taken together, the mutation detection method, and rapid and easy sample preparation rendered it highly feasible for us to identify KRAS mutations in small amounts of tissues.

Discussion

The genetic profiling of solid tumors enables us to understand the molecular signatures of tumor development and progression more effectively; it also provides clinically relevant information for an early diagnosis, and pharmacological vulnerability and resistance towards various types of cancer8. The safer acquisition of cancer cells or tissue sampling sometimes makes it difficult for pathologists to secure a proper diagnosis. Recently, genetic tests utilizing a biopsy specimen have been more commonly used for patients with lung and colorectal cancer, for the selection of chemotherapeutic reagents; this generally requires a certain amount of tissues with a high tumor-cell content14,15. However, there are cases where a low tumor cellularity, as well as a tiny amount of tumor specimens per se hampered molecular analysis16,17. Besides, although DNA extraction/purification has been routinely performed for genetic testing, the process is time- and cost-consuming and sometimes significantly dilutes the target molecule. Here, we used specimens from patients with pancreatic cancer, which is characterized by a very low tumor cell content and abundant desmoplasia; these are challenging biospecimens not only for conventional immunohistochemistry analysis, but also for molecular analysis.

In this study, we evaluated a DNA preparation method without the purification step, for the genetic testing of the FNA specimen obtained from the pancreas, using the dPCR platform. We tried two different methods; the “cell-in-droplet” method involved the direct enclosure of the target cells into the droplet, followed by dPCR, while the “water-burst” approach attempted to capture tumor-derived DNA, following the osmotic burst of cancer cells, by their exposure to pure water just before their compartmentalization during the dPCR. We found that the latter approach was superior to the “cell-in-droplet” method. In the “water-burst” method, we could detect even a small number of cells with a homozygous KRAS mutation at codon 12, in as low as 20 cells (= 40 copies) in 4,000 normal cells with wild-type KRAS, showing that it was feasible to detect dPCR-based direct driver mutations in crude tumor tissues. We found this method to be clinically relevant, as it demonstrated that the KRAS mutation was detected in needle aspirates, with the tumor lesion cells being detected in 11 of 12 needle aspirates obtained from surgically resected pancreatic tissues, and in 9 of 10 residual tumor cells obtained from FNA needles, after sending the core specimens to the pathology lab. These results indicated that the combination of the “water-burst” approach and dPCR technology has the potential for detecting mutations in a super-sensitive manner, in a specimen with low-tumor cell content, such as a pancreatic tumor.

FNA is the gold standard for pathological diagnosis in patients with different types of cancer, including PDA, owing to its high diagnostic accuracy18. Because of tumor heterogeneity, multiple punctures might be required to avoid failure during pathological assessment. Occasionally, the report was based on the assessment of a limited number of cancer cells, and the use of insufficient amounts of tumor tissues for sampling can result in false-negative results. On the other hand, the dilemma associated with FNA involves the potential risk of bleeding and needle tract seeding at the puncture site3, 19. The detection of genetic mutations might compensate for limitations in pathological assessment, and the utility of such a strategy has been demonstrated13,20.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS)-based gene panel testing has been an invaluable tool in cancer diagnostics7,21. This modality offers a great deal of information related to genetic variation from a single sample, and over time, it has become much easier to operate. Nevertheless, a certain amount of high-quality DNA from an abundant of tumor tissue requiring multiple FNA punctures is required. Besides, the handling duration for the sample preparation, library quantification, and sequencing was long22. The limit of detection of mutations is > 1%, unless additional library preparation processes, such as molecular barcoding are employed, which would make the assay more expensive and time-consuming. Besides, careful bioinformatics assessments, such as those for error elimination and reporting are required to translate the data to the clinic23. On the other hand, the dPCR assay requires only a small amount of sample (1–5 ng of DNA), and the frequency of detected mutations is as low as 0.05%24. The running cost for dPCR is affordable, and it serves as an excellent filter for identifying high-risk patients.

The most distinctive feature of this study was that we could save on the effort, cost, and time required for DNA purification by simply suspending the stored material in water and breaking the cells. Molecular tests involving dPCR have not been used widely in the clinic25. This new method would potentially play an active, significant role in routine examinations. Because of the ease of sample preparation, operations with a high mobility during testing caused the confinement of regions of genes in a small number of samples, such as that observed during the compensatory assessment using the dPCR-method for the cytopathology test. The only parameter to ensure sample quality in the water-burst method is currently the copy number of KRAS amplified. A strong correlation was observed between the copy number and the amount of template DNA when the purification step was included in the same sample sets. Additional parameters such as DNA fragment size may help to precisely determine the quality of the crude samples.

We used a commercially validated screening probe set for detecting multiple KRAS codon 12/13 mutations using a small amount of tissue sample. There are several limitations associated with using this probe set. The first is that in this study, false positives (0.27% in FNA residual tissues) were observed. The threshold of the mutation frequency determined by the assay manufacturer was 0.2%. In the crude DNA used in this method, impurities existed or DNA was fragmented, because the degrading enzymes secreted from cells might have resulted in non-specific signals for mutations. In the future, it would become necessary to determine the cut-off value unique to our method, by using a larger number of tumor specimens in clinical settings.

The second issue was that screening probe set we utilized could detect multiple KRAS mutations at codons 12, 13, or 61; this does not provide accurate information associated with specific variations in mutations. Pancreatic neoplasia has often evolved with various distributed clonal backgrounds8,26; therefore, it is essential to determine each mutation pattern, to accurately identify primary lesions or the existence of coexisting malignant or benign lesions. Besides, a mutation in KRAS alone is not sufficient to provide genetic evidence of pancreatic cancer. Therefore, improvement of the current protocol targeting related mutations in other driver genes and tumor suppressors, such as TP53 and SMAD4, is warranted. To solve this problem, we are currently developing a novel multiplex analysis method that identifies major KRAS and other gene mutations using 2D-spatial information regarding fluorescence intensity in dPCR. The dPCR system we used can distinguish two fluorescent colors27; however, a novel dPCR platform would be capable of simultaneously detecting multi-color dyes. Such a new tool might further enhance the utility of the assay during multiplex analysis, potentially allowing the detection of driver mutations across multiple genomic regions28.

The number of patients included in this study was minimal. Still, to further validate the feasibility for clinical use, it would be necessary to conduct clinical studies with a larger number of patient samples, and test various types of pancreatic tissues using FNA, ranging from benign to malignant tumor tissues. In addition to pancreatic cancer, validation studies are necessary for detecting driver mutations unique to other types of carcinomas, such as the BRAF V600E mutation observed during thyroid cancer29, as it would enhance the possibility of developing widespread clinical applications. Specifically, this approach would be clinically relevant for the minimally invasive pathological diagnosis of the tumor with a limited amount of tissue used for sampling. As observed during optional assessments using immunohistochemistry, the direct amplification and detection of key driver mutations would compensate for conventional pathological diagnosis using tissue biopsy and cytopathological analysis. Additional dPCR-based assessment of microsatellite instability may provide more detailed information regarding not only cancer diagnosis but also therapeutic implications.

In conclusion, we developed a digital PCR-based, super-sensitive assay for detecting mutations, which might resolve an issue related to the insufficiency of materials during cytopathological analysis. Our results indicated that a high rate of detection of KRAS mutations was associated with small amounts of FNA residual samples. Furthermore, using our “water-burst” method, we showed that even the DNA purification step was not necessary for detecting gene mutations in digital PCR. The straightforward and rapid protocol enables us to perform minimally invasive molecular analysis in cancer clinics.

Methods

Cell lines

Human pancreatic cancer cells (MIA PaCa-2; RCB2094) and non-cancer skin fibroblasts (NB1RGB; RCB0222) were obtained from the RIKEN cell bank (JAPAN), and grown using DMEM (MIA PaCa-2) and α-MEM (NB1RGB) media (FUJIFILM Wako chemicals, Japan) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (GE Healthcare, Chicago, Illinois, USA) and 100 U/mL penicillin–streptomycin (FUJIFILM Wako chemicals). Cell lines were grown at 37 °C with 5% CO2 and passaged at 70–80% confluence. The number of cells was counted using the Countess automated cell counter (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA).

Patients

To examine the method for detecting mutations using resected tissues, twelve patients with the resectable pancreatic disease admitted in the Sapporo Higashi Tokushukai Hospital between 2017 and 2018 were included. Ten patients from whom FNA residual samples were obtained were recruited from Asahikawa Medical University in 2019. The study protocol for patient tissue collection and scientific analysis was approved by the Tokushukai Group Ethical Committee on Human Research (#TGE00357-012) and Asahikawa Medical University Research Ethics Committee (#17002). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients before enrolment.

Fresh tissue collection and preparation from surgically resected specimens

Small tissue specimens were obtained within 30 min after the surgical resection of the PDA in the operation room. Multiple tumor areas (typically, 2–3 areas) were punctured and aspirated using 22-gauge cathelin needles (TERUMO, Tokyo, Japan) connected to 10 mL syringes. The aspirated specimens were suspended in 3 mL of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 450 μL of stock solution from the PAXgene Blood ccfDNA Tube (BD Life Sciences; Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) and stored for up to a week at 4 °C. The suspensions were centrifuged at 1,000×g for 10 min at room temperature, and the pellet was resuspended with 12 μL nuclease-free water, using a 200 μL pipette tip with a cut tip; this was immediately utilized as a PCR template.

Collection of FNA-residual specimens

After performing FNA-biopsy sampling for cytological diagnosis, FNA residual tissues were obtained using a 22-gauge Franseen biopsy needle (Acquire; Boston Scientific, Marlborough, MA, USA). Residual tissues that remained in the needle were collected in a 5.0 mL microtube by performing aspiration several times (typically, 2–3 times), followed by the emission of 3 mL of physiological saline solution, which was combined with 450 μL of stock solution from a PAXgene Blood ccfDNA Tube30 by performing inversion and mixing several times and storing the contents for up to a week at 4 °C. Also, we collected needle-wash fluid fractions, to collect the washout tissues. Each suspension was centrifuged at 1,000×g for 10 min at 4 °C. The residual pellet fraction was partly scratched and resuspended with 12 μL nuclease-free water using a 200 μL pipette tip with a cut tip, and the entire pellet of the needle-wash fraction was resuspended in 12 μL nuclease-free water. The fraction resuspended in water was directly utilized as a dPCR template. The supernatant fraction obtained after centrifugation was directly input during dPCR. Purified DNA was prepared and used as a control in conventional mutation analysis methods. DNA in the supernatant fraction was purified using a QIAmp MinElute ccfDNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), and the DNA in the pellet fraction was purified with a DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen).

Mutation detection assay using dPCR

Twenty microliters of the resuspension was mixed with 10 µL of ddPCR Supermix for Probes (no dUTP; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA), and 1 µL of ddPCR KRAS Screening Multiplex Kit that targeted KRAS exon 2 (#1863506; Bio-Rad) and template DNA solution, and then the mixture was vortexed three times at 2,500 rpm for 1 s. The PCR mixture was mixed with 70 µL Droplet Generation Oil (Bio-Rad) and compartmentalized using a QX200 droplet generator (Bio-Rad). The kit enables us to screen seven KRAS mutations (G12A/C/D/R/S/V and G13D) with a frequency > 0.2%, but specific variants cannot be determined. In the case of a tumor harboring KRAS Q61 mutation, as determined via NGS, an additional assay was performed using the ddPCR KRAS Q61 Screening Kit (Q61K/L/R/H, Bio-Rad), to evaluate the mutation status, with a cut-off > 0.5%. Specific variants also cannot be determined.

These mutation detection assays were performed using the following protocol: 10 min at 95 °C, followed by 40 cycles of 30 s at 94 °C, and 60 s at 55 °C, followed by a process for10 minutes at 98 °C (Ramp Rate; 2 °C/sec, at each step). The threshold for the absolute copy number input during the reaction and the ratio of the mutated fragments was calculated using QuantaSoft (ver 1.7; Bio-Rad), based on the Poisson distribution. Samples were scored as positive for mutant KRAS when at least five mutant droplets/reaction were detected using dPCR.

Tumor specimens and mutation analysis

To validate the mutation signature of the tumor, formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue specimens and unstained sections with a thickness of 10 μm or 4 μm (resected tissue or FNA biopsy specimen, respectively) were prepared. Genomic DNA was isolated using the GeneRead DNA FFPE Kit (Qiagen), and finally eluted with 30 μL of elution buffer, as described previously31. The purified DNA was quantified using the Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit on a Qubit4 fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Somatic mutations in the primary tumor of FFPE tissue specimens were also profiled using targeted amplicon sequencing techniques on the Ion AmpliSeq Custom Next-Generation Sequencing DNA panels, which were designed using the Ion AmpliSeq Designer Website (https://www.ampliseq.com), for targeting 8 PDA-related genes, namely KRAS, TP53, SMAD4, CDKN2A, GNAS, PIK3CA, BRAF, and STK11 (Supplementary Table). Details regarding the sequencing analysis are described in the Supplementary Information.

Abbreviations

- dPCR:

-

Digital PCR

- FNA:

-

Fine-needle aspiration

- PDA:

-

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

References

Hewitt, M. J. et al. EUS-guided FNA for diagnosis of solid pancreatic neoplasms: a meta-analysis. Gastrointest. Endosc. 75, 319–331 (2012).

Wang, K. X. et al. Assessment of morbidity and mortality associated with EUS-guided FNA: a systematic review. Gastrointest. Endosc. 73, 283–290 (2011).

Kawabata, H. et al. Genetic analysis of postoperative recurrence of pancreatic cancer potentially owing to needle tract seeding during EUS-FNB. Endosc. Int. Open 7, E1768–E1772 (2019).

Eloubeidi, M. A. et al. Yield of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy in patients with suspected pancreatic carcinoma. Cancer 99, 285–292 (2003).

Da Cunha Santos, G. et al. A proposal for cellularity assessment for EGFR mutational analysis with a correlation with DNA yield and evaluation of the number of sections obtained from cell blocks for immunohistochemistry in non-small cell lung carcinoma. J. Clin. Pathol. 69, 607–611 (2016).

Bor, R. et al. Prospective comparison of slow-pull and standard suction techniques of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration in the diagnosis of solid pancreatic cancer. BMC Gastroenterol. 19, 6 (2019).

Roy-Chowdhuri, S. et al. Concurrent fine needle aspirations and core needle biopsies: a comparative study of substrates for next-generation sequencing in solid organ malignancies. Mod Pathol 30, 499–508 (2017).

Patra, K. C., Bardeesy, N. & Mizukami, Y. Diversity of precursor lesions for pancreatic cancer: the genetics and biology of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 8, e86 (2017).

How-Kit, A. et al. Ultrasensitive detection and identification of BRAF V600 mutations in fresh frozen, FFPE, and plasma samples of melanoma patients by E-ice-COLD-PCR. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 406, 5513–5520 (2014).

Pupilli, C. et al. Circulating BRAFV600E in the diagnosis and follow-up of differentiated papillary thyroid carcinoma. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 98, 3359–3365 (2013).

Luke, J. J. et al. Realizing the potential of plasma genotyping in an age of genotype-directed therapies. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 106, dju214 (2014).

Beaver, J. A. et al. Detection of cancer DNA in plasma of patients with early-stage breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 20, 2643–2650 (2014).

Sho, S. et al. Digital PCR improves mutation analysis in pancreas fine needle aspiration biopsy specimens. PLoS ONE 12, e0170897 (2017).

Russo, M. et al. Tumor heterogeneity and lesion-specific response to targeted therapy in colorectal cancer. Cancer Discov. 6, 147–153 (2016).

Vendrell, J. A. et al. Detection of known and novel ALK fusion transcripts in lung cancer patients using next-generation sequencing approaches. Sci. Rep. 7, 12510 (2017).

Lhermitte, B. et al. Adequately defining tumor cell proportion in tissue samples for molecular testing improves interobserver reproducibility of its assessment. Virchows Arch. 470, 21–27 (2016).

Dufraing, K. et al. External quality assessment identifies training needs to determine the neoplastic cell content for biomarker testing. J. Mol. Diagn. 20, 455–464 (2018).

Chen, G., Liu, S., Zhao, Y., Dai, M. & Zhang, T. Diagnostic accuracy of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration for pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis. Pancreatology 13, 298–304 (2013).

Gleeson, F. C., Lee, J. H. & Dewitt, J. M. Tumor seeding associated with selected gastrointestinal endoscopic interventions. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 16, 1385–1388 (2018).

Kanagal-Shamanna, R. et al. Next-generation sequencing-based multi-gene mutation profiling of solid tumors using fine needle aspiration samples: promises and challenges for routine clinical diagnostics. Mod. Pathol. 27, 314–327 (2014).

Muller, S. et al. Next-generation sequencing reveals novel differentially regulated mRNAs, lncRNAs, miRNAs, sdRNAs and a piRNA in pancreatic cancer. Mol. Cancer 14, 94 (2015).

Esling, P., Lejzerowicz, F. & Pawlowski, J. Accurate multiplexing and filtering for high-throughput amplicon-sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, 2513–2524 (2015).

Mallampati, S. et al. Rational “error elimination” approach to evaluating molecular barcoded next-generation sequencing data identifies low-frequency mutations in hematologic malignancies. J. Mol. Diagn. 21, 471–482 (2019).

Ono, Y. et al. An improved digital polymerase chain reaction protocol to capture low-copy KRAS mutations in plasma cell-free DNA by resolving “subsampling” issues. Mol. Oncol. 11, 1448–1458 (2017).

Huggett, J. F., Cowen, S. & Foy, C. A. Considerations for digital PCR as an accurate molecular diagnostic tool. Clin. Chem. 61, 79–88 (2015).

Omori, Y. et al. Pathways of progression from intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm to pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma based on molecular features. Gastroenterology 156, 647–661 (2019).

Alcaide, M. et al. A novel multiplex droplet digital pcr assay to identify and quantify kras mutations in clinical specimens. J. Mol. Diagn. 21, 214–227 (2019).

Madic, J. et al. Three-color crystal digital PCR. Biomol. Detect. Quantif. 10, 34–46 (2016).

Fagin, J. A. & Wells, S. A. Jr. Biologic and Clinical Perspectives on Thyroid Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 375, 1054–1067 (2016).

Schmidt, B. et al. Liquid biopsy - performance of the PAXgene(R) blood ccfDNA tubes for the isolation and characterization of cell-free plasma DNA from tumor patients. Clin. Chim. Acta 469, 94–98 (2017).

Nagai, K. et al. Metachronous intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms disseminate via the pancreatic duct following resection. Mod. Pathol. 33, 971–980 (2019).

Acknowledgements

We thank Yuko Hayakawa for performing next-generation sequencing analysis of resected tumor and biopsy specimens. We also thank Nobue Tamamura (Asahikawa Medical University) for tissue sample preparation. This study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI via grant number 17K09472, the Suzuken Memorial Foundation, and the Suhara Memorial Foundation; all financial support was provided to Y.M. We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.O., A.H., C.M., and M.S. acquired and analyzed data. Y.O., A.H., and Y.M. designed the study and wrote the article. R.W. and H.K. collected the resected tissues and prepared samples. A.H., H.S., H.K., T.O., and T.G. collected the FNA residual tissues and prepared samples. H.K. and T.O. supervised the study. All the authors critically reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Y.O. and Y.M. received funding from the Hitachi High-Technologies Corporation (Tokyo, Japan). The other authors declare no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ono, Y., Hayashi, A., Maeda, C. et al. Time-saving method for directly amplifying and capturing a minimal amount of pancreatic tumor-derived mutations from fine-needle aspirates using digital PCR. Sci Rep 10, 12332 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-69221-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-69221-6

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.