Abstract

The Bełchatów Lignite Mine of Poland is a treasure-cove for mid-to late Miocene plant and animal fossils, deposited in a slow-flowing river valley with swamps and oxbow lakes. Here, we report the finding of abundant fossil anomopod cladocerans. Some are three-dimensionally preserved, including the taxonomically important trunk limbs. They pertain to the families Chydoridae and Bosminidae, with species similar to but distinct from modern ones. All are members of the zooplankton, though some are littoral while others are pelagic in nature. Morphological stasis in these families is not outspoken as in the Daphniidae and the stasis hypothesis, based on ephippia only, is challenged. The absence of Daphnia is conspicuous and ascribed to a combination of fish predation and local water chemistry. Its place in the oxbow lakes is taken by at least two Bosmina species, one of which is undescribed. We consider this a case of paleo-competitive release. For Bosminidae, these are the first certified fossils predating the Pleistocene.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The lignite mine at Bełchatów, Central Poland (Fig. 1), has recently yielded abundant Miocene remains of several species of branchiopod microcrustaceans. They pertain to the order Anomopoda or water fleas, families Chydoridae and Bosminidae. The main synapomorphy of the anomopods is the ephippium, a structure in which sexual or resting eggs are deposited and that forms when external conditions deteriorate. The Daphniidae include the well-known and speciose genus Daphnia, a highly specialized pelagic component of the freshwater zooplankton. The ephippium fossilizes well and is mostly the only structure that survives as a fossil. The Chydoridae are mostly found in the littoral of lakes and ponds, among water plants. The Bosminidae are pelagic, like Daphnia, but are much smaller (around 0.5 mm in body size) while Daphnia and other daphniids may reach up to 6–7 mm.

(A) View of the Bełchatów Lignite Mine outcrop (photo from the nineties of the twentieth century, when the material was collected). The sedimentary unit with deposits with the cladoceran fossils is to the lower right of the picture (photo: G. Worobiec). (B) Piece of mudstone with cladoceran remains (Collection KRAM-P 225, stored in the W. Szafer Institute of Botany, Polish Academy of Sciences). On the exposed surface leaves of trees and shrubs as well as the water plant Potamogeton (red circle) are seen (photo: A. Pociecha).

The fossil-bearing deposits belong to a clayey-sandy (I-P) unit considered to be of mid to late Miocene age1,2. Beside by geology, this age is supported by fission track dating, and fossils of different animal (mollusks, fish) and plant (higher plants, water plants and algae) groups1,2,3,4,5,6,7. The fission track ages were 16.5 to 18.1 million years, while the Miocene, also known as the age of mammals, extended from 23 to 5.3 million years BP.

The Branchiopoda (a class of the Crustacea composed ten extant orders) include some of the most ancient extant crustaceans (the Anostraca or fairy shrimp) with several credible fossils8. However, the fossil record is patchy. While the oldest known anostracan-like representatives date back to the Cambrian, fossils of the four extant so-called cladoceran orders, with an estimated 1,000 extant species, is poor9 and somewhat paradoxical. The order Ctenopoda is known from ca 60 extant species and several Mesozoic fossils (possibly representing orders in their own right) but is rare in the most abundant source of fossils, the sediments of late Pleistocene–Holocene lakes10,11. The Anomopoda, in contrast, have to date a limited Mesozoic fossil record, but their subfossils abound in Holocene lake sediments.

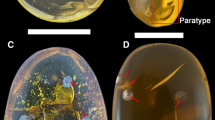

The family Chydoridae is represented in Bełchatów by at least four genera: Alona, Acroperus, Camptocercus, and Chydorus. Alona s.l. rivals Daphnia as the most species-rich genus of the order9. All Alona fossils seen so far had two connected head-pores (Fig. 2), placing them near or in the somewhat controversial genus Biapertura. In modern European faunas, and except for Biapertura affinis, three-pored species are dominant, while two-pored ones tend to be typical of warm-climate faunas. The postabdomen, another typical anomopod structure functioning more or less as a ‘tail’, is similar but not identical to that of Biapertura affinis. Furthermore, distinct other species (Fig. 2) have been found as well.

Another type of fossils (Fig. 3) shares characters of the genera Acroperus and Camptocercus. Some body parts suggest the presence of Acroperus cf. harpae, others are Campocercus like. One three-dimensional fossil of a first trunk limb (P1) with soft parts preserved shows an IDL (inner distal lobe) with two setae and a moderately well developed claw. In Acroperus, a seta instead of a claw is found here. In Camptocercus, P1 has a big hook here, and our fossils are therefore intermediate between both genera, suggesting the fossil to belong to an extinct ancestral stage. The genus Chydorus is represented by C. sphaericus-like fossils (Fig. 3), but the postabdomen is needed to decide on its taxonomic status.

Acroperus-Camptocercus from Miocene mudstone at Bełchatów [(A) complete animal with shell, headshield, and first antenna; (B) abdomen; (C) shell; (D) claw; (E) shell with abdomen; (F) headshield with soft parts, viz. first and second trunk limbs with IDL setae conserved] (photo: A. Pociecha, E. Zawisza).

Significantly, Bosminidae in our material were almost as abundant as Alona, while in this family no pre-Pleistocene fossils were previously known at all. Most body parts have been recovered (Fig. 4), but not the postabdomen, which is diagnostic. There is strong variation in the fossils, like in the length of the first antenna (compare Fig. 4B with Fig. 4C,E) and the posterior mucro of the valve. It is impossible to decide whether these antennae belong to several or to a single cyclomorphotic species. However, the distinctly swollen mucros like in Fig. 4A, arrow, are not known in any modern Bosmina, and suggest an extinct taxon.

Daphniid fossil evidence goes back to the Jurassic/Cretaceous boundary. Fossils are fairly common but only consist of resting eggs (ephippia). Ephippia can tentatively be identified to genus level, which has led to the idea that the two subfamilies of Daphniidae have been around, apparently unchanged, for more than 140 million years9. This is known as the morphological stasis hypothesis. Its factual basis is weak although we accept that true Daphnia ephippia occur in the cretaceous of China, Mongolia and Australia9. Credible ephippia have also been isolated from Eocene age Messel pit-oil shales11. Moina (a water flea related to Daphnia) ephippia have been recovered from the early Miocene Barstow formation12,13,14. In the latter place, fossils are three-dimensional, like in our case in Bełchatów. It should be emphasized, however, that at Bełchatów no daphniid fossils have to date been discovered.

A variety of plant and animal groups, including water plants like Potamogeton have been documented from the Bełchatów site. Many are as beautifully preserved as the cladocerans3,4,5,6,7 and attempts have been made to reconstruct the climatic environment in which they lived. It is suggested to have been warmer than today (average 13.5°–16.5°C, cooling down gradually towards the end of the Miocene). The water was probably slowly flowing, through what may have been a swamp or a group of oxbow lakes from freshwater ecosystems2,15.

That we recovered no daphniid fossils may refine our insight into the nature of the Bełchatów aquatic environment: We favour the idea of a series of shallow oxbow lakes in a climate warmer than todays, with at least locally an abundance of macrophytes. Chydorids thrive in such environments, and the genus Simocephalus among daphniids also prefers such an environment. Simocephalus is quite common and widespread in modern weedy lakes but it has not been found in Bełchatów either. Like Daphnia, Bosminids are truly planktonic and need open water. Therefore, the Bełchatów lakes were probably a patchwork of macrophyte beds and open water.

So where did all the daphniids go? Daphniids are also relatively large species (up to several mm in size), while chydorids and bosminids are typically below a millimeter in size. This suggests size-selective predation on the zooplankton, most probably by fish16. Fish (tench, pike, and unidentified species) were present at Bełchatów4, at least until the middle Miocene. Tench is an omnivore and Pike is zooplanktivorous in its early stages, turning to piscivory in later life. Predation-driven exclusion of these large cladocerans may therefore well have acted in concert with the physical environment.

Predatory exclusion is seldom absolute, especially in a non-tropical climate with a cold season (‘winter’) during which predation is relaxed. This allows the prey to recover. In Bełchatów, we see no such a recovery, so another factor must have intervened. We suggest this may have been linked to water chemistry. Cladocerans, though of worldwide occurrence, are sensitive to water chemistry, more than the copepods, the second main group making up the zooplankton. We are unable to specify the precise nature behind the chemical exclusion of daphniids, but there are many examples of lakes in which Cladocera are chemically depressed. Sometimes, like in Lake Tanganyika (Africa), and the Mallili lakes (Indonesia), Cladocera are excluded altogether17,18.

In conclusion, our Miocene assemblage significantly expand our insights in anomopod evolution. They resemble modern faunas but at the same time show stronger signs of evolution at the species and at the genus level than expected under the morphological stasis hypothesis based on Daphnia ephippia. We also find clear indications of a species diversity that resembles todays’, with morphologies that look familiar at first sight but prove divergent in the details.

Bosminid fossils used to be known from the Pleistocene only, but in the Bełchatów fauna they are remarkably abundant and some of them show an unfamiliar morphology. This is best interpreted as a case of paleo-competitive release. Daphniids normally dominate the pelagic and keep bosminid abundances down. But their absence gives these small crustaceans a chance to prosper and dominate the open waters.

Methods

Cladoceran remains were first found during palynological analysis of samples from a collection encoded KRAM-P 225. Only recently, the material containing cladocerans was examined in detail.

The fossils include exoskeletons or almost complete animals, and are encased in mudstone from which they can be isolated by gentle preparation19. Around 50 gr of mudstone was incubated with a 10% solution of sodium hexametaphosphate and was allowed to macerate overnight under gentle heating. After washing with distilled water, the sample was heated with 10% KOH for twenty minutes, washed on a 30 μm sieve, and stained with safranin. We applied no stirring, not to dislocate the delicate fossils. Some showed almost intact soft parts, such as trunk limbs and mouth parts (the labrum). They were, in fact, better preserved than most Holocene (sub)fossils. Often, the fossils were three-dimensional with well preserved soft parts.

References

Burchart, J., Kasza, L. & Lorenc, S. Fission-track zircon dating of tuffitic intercalations (Tonstein) in the Brown–Coal Mine “Bełchatów”. Bull. Pol. Acad. Sci. Earth Sci. 36(3–4), 281–286 (1988).

Krzyszkowski, D. & Winter, H. Stratigraphic position and sedimentary features of the Tertiary Uppermost Fluvial Member in the Kleszczów Graben, central Poland. Ann. Soc. Geol. Pol. 66, 17–33 (1996).

Stuchlik, L., Szynkiewicz, A., Łańcucka-Środoniowa, M. & Zastawniak, E. Wyniki dotychczasowych badań paleobotanicznych trzeciorzędowych węgli brunatnych złoża “Bełchatów” (summary: Results of the hitherto palaeobotanical investigations of the Tertiary brown coal bed “Bełchatów” (Central Poland). Acta Palaeobot. 30(1–2), 259–305 (1990).

Kovalchuk, O., Nadachowski, A., Świdnicka, E., & Stefaniak, K. Fishes from the Miocene lacustrine sequence of Bełchatów (Poland). Hist. Biol. https://doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2018.1561671 (2019).

Worobiec, E. & Worobiec, G. Miocene palynoflora from the KRAM-P 218 leaf assemblage from the Bełchatów Lignite Mine (Central Poland). Acta Palaeobot. 56(2), 499–517 (2016).

Worobiec, G. & Worobiec, E. Wetland vegetation from the Miocene deposits of the Bełchatów Lignite Mine (central Poland). Palaeontol. Electron. 22(63), 1–38 (2019).

Kowalski, K. & Rzebik-Kowalska, B. Paleoecology of the Miocene fossil mammal fauna from Bełchatów (Poland). Acta Theriol. 47(Supp. 1), 115–126 (2002).

Dumont, H. J. & Negrea, S. V. Introduction to the Class Branchiopoda (Backhuys, Leiden, 2002).

Van Damme, K. & Kotov, A. A. The fossil record of the Cladocera (Crustacea: Branchiopoda): Evidence and hypotheses. Earth Sci. Rev. 163, 162–189 (2016).

Szeroczyńska, K. & Sarmaja-Korjonen, K. Atlas of Subfossil Cladocera from Central and Northern Europe. 1–84 (Towarzystwo Przyjaciół Dolnej Wisły: Świecie, Polska, 2007).

Wojewódka, M., Sinev, A. Y., Zawisza, E. & Stańczak, J. A guide to the identification of subfossil chydorid Cladocera (Crustacea: Branchiopoda) from lake sediments of Central America and the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico: part II. J. Paleolimnol. 63(1), 37–64 (2020).

Wappler, T. et al. Before the ‘Big Chill’: A preliminary overview of arthropods from the middle Miocene of Iceland (Insecta, Crustacea). Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 401, 1–12 (2014).

Peñalver, E., Martínez-Delclòs, X. & De Renzi, M. Registro de pulgas de agua [Cladocera: Daphniidae Daphnia (Ctenodaphnia)] en el Mioceno de Rubielos de Mora (Teruel, España). Comunicaciones de la II Reunión de Tafonomía y Fosilización, 13–15 June 1996; Zaragoza, 311–317 (1996).

Korovchinsky, N. M. The Cladocera (Crustacea: Branchiopoda) as a relict group. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 147(1), 109–124 (2006).

Wilczyński, R. Dotychczasowe wyniki badań podstawowych serii poznańskiej w świetle geologiczno-inżynierskich problemów prowadzenia robót górniczych w KWB “Bełchatów” (summary: The hitherto existing results of the Poznań suite in the light of geological-engineering problems of carrying mining works in the “Bełchatów” brown coal open mine). Acta Universitatis Wratislaviensis, 1354, Prace Geologiczno-Mineralogiczne 24, 91–108 (1992).

Brooks, J. L. & Dodson, S. I. Predation, body size, and composition of plankton. Science 150, 28–35 (1965).

Sabo, E. et al. The plankton community of Lake Matano: factors regulating plankton composition and relative abundance in an ancient, tropical lake of Indonesia. Hydrobiologia 615, 225–235 (2008).

Coulter, G. W., Tiercelin, J. J., Mondegeur, A., Hecky, R. E. & Spigel, R. H. Lake Tanganyika and Its Life (Natural HIstory Museum Publications, London and Oxford, 1991).

Frey, D. G. Cladocera analysis. In Handbook of Holocene Palaeoecology and Palaeohydrology (ed. Berglund, B. E.) 667–692 (Wiley, New York, 1986).

Acknowledgements

This work was co-supported by: Institute of Nature Conservation, Polish Academy of Sciences, Institute of Geological Sciences, Polish Academy of Sciences and W. Szafer Institute of Botany, Polish Academy of Sciences through the statutory funds.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.J.D., A.P., E.Z., K.S. processed data and analysed results. A.P. and E.Z. prepared display items. E.W. and G.W. provided materials for analysis. H.J.D. wrote the manuscript with contributions from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Dumont, H.J., Pociecha, A., Zawisza, E. et al. Miocene cladocera from Poland. Sci Rep 10, 12107 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-69024-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-69024-9

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.