Abstract

Many of today’s most pressing societal concerns require decisions which take into account a distant and uncertain future. Recent developments in strategic decision-making suggest that individuals, or a small group of individuals, can unilaterally influence the collective outcome of such complex social dilemmas. However, these results do not account for the extent to which decisions are moderated by uncertainty in the probability or timing of future outcomes that characterise the valuation of a (distant) uncertain future. Here we develop a general framework that captures interactions among uncertainty, the resulting time-inconsistent discounting, and their consequences for decision-making processes. In deterministic limits, existing theories can be recovered. More importantly, new insights are obtained into the possibilities for strategic influence when the valuation of the future is uncertain. We show that in order to unilaterally promote and sustain cooperation in social dilemmas, decisions of generous and extortionate strategies should be adjusted to the level of uncertainty. In particular, generous payoff relations cannot be enforced during periods of greater risk (which we term the “generosity gap”), unless the strategic enforcer orients their strategy towards a more distant future by consistently choosing “selfless” cooperative decisions; likewise, the possibilities for extortion are directly limited by the level of uncertainty. Our results have implications for policies that aim to solve societal concerns with consequences for a distant future and provides a theoretical starting point for investigating how collaborative decision-making can help solve long-standing societal dilemmas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

If individuals choose between rewards that differ only in amount, timing, or certainty, decisions are relatively predictable because general principles of choice apply1. For example, individuals tend to choose higher rewards over lower ones, sooner rewards over later ones, and secure rewards over risky ones. Indeed, such decisions make sense from both an economic and evolutionary perspective and are observed in both humans and animals1,2. Predicting decisions becomes more challenging when the choice options differ in a combination of these factors. For example, it can be difficult to predict how an individual chooses between a small but immediate reward and a large but distant one. Although such combinations of different features usually require trade-offs in decision-making, their salient features can be studied from the perspective of discounting on the basis of the expected time (delay discounting) or likelihood of their occurrence (probability discounting)1,3,4,5. Indeed, these discounting methods are positively correlated4,5.

Game theory provides a unifying framework through which these decision-making processes can be formalised under a variety of complex situations. The defining feature of games is that their outcomes depend on not only one’s own decision, but also on the decisions of others. This interdependence inherently causes uncertainty in probable outcomes and payoffs. It becomes more challenging in repeated games in which a series of interactions occur over time and individuals need to make strategic decisions that take into account how their past and current decisions can influence future payoffs under reciprocal altruism, antagonism, punishment or reward6,7,8.

Of particular interest are social dilemmas in which immediate self-interests conflict with long-term collective interests. In these complex social and economic situations, discounting and reciprocity have been shown to interactively influence the level of “selfless” cooperative decisions9,10,11. This interaction also serves as a plausible explanation for the changing (cooperative) behaviours throughout the life span of humans12,13,14.

Understanding if, and how, strategic decisions are affected by delay and probability discounting is becoming more and more important because many of today’s most pressing societal concerns, like climate change, require current decisions to take into account the consequences for an uncertain distant future15,16,17. In these complex settings, theoretical models for both delay and probability discounting methods use discount rates that decrease over time2,18,19,20,21,22. These hyperbolic-like functions have indeed proven to be a better fit to empirical discounting rates than traditional time-consistent exponential functions that tend to discount the far future too fast1,21,23.

Recent developments in the theory of direct reciprocity and strategic behaviour suggest that a single, or small group of strategic individuals, can have a much larger influence on other players’ decisions than previously anticipated24,25. In particular, these theories enable strategic individuals to solve social dilemmas by applying generous strategies that can unilaterally “enforce” mutual cooperation in a large group of decision-makers25,26. However, these theories are built on traditional time-consistent discounting methods, that leave out important elements of the psychology of discounting16. In fact, the current assumptions on discount factors in repeated social dilemmas can easily cause discrepancies between theoretical cooperation levels and observed experimental behaviours27,28.

Although these novel theories provide important perspectives for policy-makers when exerting influence in long-run collective outcomes, it is not yet known how the intricate strategies hold up under more sophisticated discounting methods that take the inherent uncertainty of future outcomes into account. By incorporating uncertainty about the discount factor into the framework of repeated games, we generalise the existing theories on strategic play and show how individuals can exert a significant level of influence even under time-inconsistent discounting. The proposed discounting framework is consistent with the hyperbolic form observed by experimentalists and, in its deterministic limits, complies with existing theories of strategic play. We postulate that this theoretical framework is more appropriate for describing real-world decision making procedures in which judgements on the number of interactions is made under uncertainty27 or the far-distant future is crucial for the success of current strategic decisions16.

Illustration of a social dilemma. Dots represent players: cooperators are indicated by blue dots and defectors by red dots. The size of the dot indicates the payoff of the player. A group of cooperators typically create a maximum collective benefit. In mixed groups defectors benefit from cooperators and receive larger payoffs. When all individuals defect the collective benefit is typically minimum as in the “tragedy of the commons”29.

To show the utility of our results, we consider a general class of n-player social dilemmas15,16,25. In the model individual players repeatedly choose to cooperate or defect. A player’s payoff in a given round depends on their decision and the number of cooperating co-players25,30,31. If \(z\in \{0,1,\dots ,n-1\}\) co-players cooperate, then the single-round payoff for cooperation is \(a_z\), and the single-round payoff for defection is \(b_z\). We only assume the single-round payoffs satisfy three characteristic properties of social dilemmas25,32: first, irrespective of one’s own decision to cooperate or defect, players prefer their co-players to cooperate; second, in a group of cooperators and defectors, defecting players have a strict advantage; finally, the mutual cooperation payoff (\(a_{n-1}\)) is more beneficial than the mutual defection payoff (\(b_0\)), see Fig. 1. These characteristics are able to capture a variety of complex situations in which payoffs can non-linearly depend on the decisions of one’s co-players and include the prisoners dilemma game, the public goods game, the volunteers dilemma, the n-player snowdrift game31, the n-player stag hunt game33, and many more.

Discounting an uncertain future

In traditional repeated games with finite but undetermined time horizons, the expected number of rounds is determined by a fixed and common discount factor \(\delta \in (0,1)\) that, given the current round of interactions, determines the probability of a next round, and is therefore also referred to as a continuation probability. Consequently, expected discounted payoffs are calculated using a discounting function \(\delta ^t\) that corresponds to deterministic discrete-time exponential discounting16,34,35. However, if one is uncertain about the discount factor or the probability for next interactions27, then the value of the payoffs relying on future interactions are uncertain as well and it is not the case that a fixed parameter \(\delta\) can be used to represent the discounted value of payoffs.

Under this uncertainty, hyperbolic discounting functions typically refer to relatively short-run decision-making behaviour under delayed or probabilistic rewards5,23,36,37. A similar argument can be made for discounting the distant future: strategic decisions with consequences for the distant future are made not knowing the relevant outcome and should therefore be discounted probabilistically21,23. In the spirit of gamma discounting21, let us thus assume that discount factors are described by a random variable x, whose probability density function \(f(x,\alpha ,\beta )\), defined for all \(x\in [0,1]\), is of the beta form

where \(\mathrm {B}(\alpha ,\beta )\) is the beta function. Indeed, the beta distribution is often used to describe the distribution of a bounded random variable (like an uncertain probability) and is thus a suitable choice38,39. The obtained effective discounting function21 becomes

where \(\Gamma (\cdot )\) indicates the gamma function. This effective discounting function indicates how payoffs are discounted when the probability for future interactions and their outcomes are uncertain (Fig. 2).

Discounting uncertain future outcomes. Strategic decisions in social dilemmas are affected by the valuation of probabilistic long-run outcomes that result from collective behaviour and the probability for continued interaction. Different outcomes, indicated by the partially filled coloured circles in panel (a), can be valued with different discount factors depending on expected time and likelihood of occurrence. Theoretically these psychological and economic complexities in decision-making can be modelled by an uncertain discount factor shown in panel (b). This results in the hyperbolic-like effective discounting function shown in panel (c) and equation (1). In the illustration the shape parameters of the beta distribution in panel (b) are \(\alpha =5\) and \(\beta =\frac{5}{4}\), leading to a mean discount factor of 0.8 and a variance of approximately 0.022.

As one would expect, the payoffs that are received now are not subject to uncertainty and are “discounted” by the factor \(d(0)=1\). Interestingly, the rate of change of equation (1) is

and thus supports the empirically validated feature of hyperbolic discounting in which the discount rate decreases monotonically over time1, 2 and thereby suitably discounts the distant future with the lowest possible rate21,23.

To theoretically investigate how this affects strategic decision-making, one can incorporate the effective discount function in equation (1) in a repeated game. Denoting by \(\pi _i(t)\) the expected payoff of player i in round t, the average discounted payoff of player i can be written as

For \(\beta >1\) the series of the effective discounting function in the denominator of equation (3) converges to

indicating that the shape parameters of the beta distribution analytically determine the normalisation factor of the average discounted payoff of players. It is worth pointing out that the requirement \(\beta >1\) rules out the possibility for a uniform and u-shaped distribution, indicating that players cannot be “completely” uncertain about how to value an uncertain future.

Influencing an uncertain future

A strategic individual is typically interested in maximising their influence in a decision-making process by employing a decision-making strategy that guarantees a desired relative performance. One could, for instance, be interested in outperforming others via extortionate ZD strategies or ensuring that others do well via generous ZD strategies24,25,40. When there is no discounting or future payoffs are discounted deterministically, individuals can indeed strategically influence outcomes by employing a fixed strategy that enforces a linear payoff relation in the average discounted payoff of their co-players (\(\pi _{-i}\)) and their own average discounted payoff24,25,35:

The strategy parameter s is commonly referred to as the slope of the linear payoff relation and determines how \(\pi _{-i}\) varies with \(\pi _i\), while the parameter l is referred to as the baseline payoff that determines the average discounted payoffs when all players employ the same ZD strategy25. While a fixed strategy suffices in the deterministic case, equation (2) indicates that uncertainty does change discount rates, which have to be taken into account in one’s effort to strategically influence uncertain future outcomes. This necessarily requires one’s decision-making strategy to adapt to the changing discount rates and thus become time-varying. In section 2 of the Supplementary Information we show how risk-adjusted strategies cope with uncertainty and by doing so, allow a strategic player to strategically influence an uncertain future. However, the uncertainties, that are so common in the real-world, come with fundamental limitations that previous theories have overlooked.

The generosity gap

Strategies that can enforce generous payoff relations (\(0<s<1,l=a_{n-1}\)) have received significant scientific attention for their ability to unilaterally promote and sustain cooperative behaviour via direct reciprocity7,25,26 and evolution40,41. We find that such strategies do not exist when the uncertain future is discounted using the hyperbolic-like effective discounting function in equation (1) (see Supplementary Information section 2 for more details). Due to the time-varying discount rates these strategies become well-defined only after a significant amount of time, i.e. the generosity gap (see Fig. 3), has passed:

Equation (6) implies that the more uncertain an “as if” constant mean discount factor becomes, the longer a strategic player is prevented from enforcing a generous payoff relation, unless they simply always cooperate (see Supplementary Information section 2 for details). After the generosity gap has passed, the effective discounting function has decreased to such an extent that a desired generous payoff relation can be enforced, but only over the averaged payoffs received beyond the generosity gap that are discounted with a relatively constant and low discount rate. This indicates that under uncertainty a generous strategic player can only solve social dilemmas by completely setting aside their immediate and short-term interests and adjust their strategic influence to a notably far-distant future. Interestingly, if the discount factor becomes certain, the deterministic limits of equation (1) are consistent with existing theories in which generous payoff relations can be enforced without any generosity gap (see the Supplementary Information section 2 for more details).

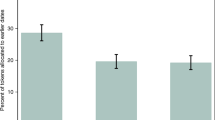

The generosity gap. Numerical example of the conditional probability for the strategic player to mutually cooperate with their co-players for a variable shape parameter \(\alpha\), a fixed mean discount factor \(\mu =0.8\), and \(\beta =\frac{\alpha (1-\mu )}{\mu }\). When the variance in the discount factor increases (for lower \(\alpha\) values) it takes longer for the generous risk-adjusted strategy to become well-defined. Consequently, the generosity gap, that indicates the time the strategic player cannot enforce a generous payoff relation, increases in length.

Extortion in an uncertain future

When future interactions are at least as likely as a termination of the game, the beta distribution is symmetric or negatively skewed (\(\alpha \ge \beta\)) and strategic decisions tend to include at least one future interaction. In the Supplementary information (section 2) we show that for many social dilemmas, in fact, this is a requirement for the possibility to strategically influence an uncertain future with an extortionate payoff relation (\(0<s<1, l=b_0\)) that can promote cooperation and typically ensures a beneficial relative performance of the strategic player. For any positively skewed distribution the low mean discount factor does not allow strategic influence because payoffs are discounted too fast and others cannot “learn” to cooperate with the extortioner7,26. This additional requirement also provides insight into how uncertain the discount factor or continuation probability can be before losing the possibility to enforce a desired extortionate payoff relation. For symmetric or negatively skewed distributions the theoretical maximum variance that a strategic player can deal with while exerting an extortionate payoff relation occurs when \(\alpha =\beta\), and evaluates as

Now let us suppose the strategic player has estimated the distribution of the discount factor21. Then, exactly how extortionate can a payoff relation be? In general, this depends on the one-shot payoffs and the mean of the beta distribution given by \(\mu =\frac{\alpha }{\alpha +\beta }\). Figure 4 illustrates this for the linear public goods game and the n-player snowdrift game31. In both games, an increased mean discount factor slows down discounting and enables more extortionate influence (see Supplementary Information section 2 for a general characterisation). However, as with generosity there is a catch: an increased mean discount factor comes at the price of a decreased maximum allowable variance as determined by equation (7). Thus, when discounting becomes slower and the distant future becomes more relevant for today’s decisions, an extortioner is required to be more certain about the valuation of events further in the future.

Enforceable slopes and mean discount factors. Left: Numerical examples of enforceable slopes by extortionate strategies when \(\mu =\frac{9}{10}\). In an n-player snowdrift game with benefit \(b=\frac{5}{4}\), cost \(c=1\) and \(n=3\), extortionate strategies can only enforce slopes after the vertical line at \(s=1-\frac{c}{b(n-1)}=\frac{6}{10}\). Every slope s for which the blue curve is below \(\mu\) is enforceable (blue region). Right: in a linear public goods game with multiplier \(r=\frac{12}{10}\), cost \(c=1\) and \(n=3\), extortionate strategies can enforce any slope s for which the red curve is under \(\mu\), this is indicated by the red region. See the Supplementary Information section 3 for detailed descriptions of the games.

Discussion

Classic theories of strategic decision-making rely on how one’s actions can affect their future. If one would consider to defect by choosing selfishly at some point in time, how large will the consequences of retaliation be? And is the fear of retaliation from others enough to sustain cooperation even when the immediate benefit of defection is large? These strategic trade-offs are commonly referred to as “the shadow of the future” and provide an elegant theoretical explanation for the emergence of cooperative behaviour of rational players in repeated social dilemmas8. However, even with moderate discount factors, the exponential discounting functions used in these theories attribute meaningless significance to the distant future23 and do not take into account empirically observed time-inconsistent valuations, making them less suitable for modelling strategic decisions that affect a distant future. More recently, strategic behaviour has been studied from an alternative perspective by identifying decision-making strategies that can unilaterally exert strategic influence on the long-run collective behaviour. Because they require minimal assumptions on the behaviour of others, such strategies are of particularly interest to human decision-making7. However, also these theories are built upon valuations of future scenarios that, in reality, are riddled with uncertainties in the probability or timing of payoffs that are likely to influence strategic decisions27,42.

Here we have modelled these uncertainties with a discounting method that exhibits the characteristic features of empirically validated delay, probability and social discounting methods1,5. Using the proposed framework, existing theories of strategic decision-making can be recovered in deterministic limits and new insights are obtained into the interaction between uncertainty, discounting and the possibilities for strategic influence. Namely, in social dilemmas, uncertainty leads to generosity gaps that require generous strategic influence to be adjusted to the longer term. These potentially long periods of time in which no generous payoff relation can be enforced may also contribute to the empirically observed inconsistencies in strategic influence and cooperation levels over time25,26. On the other hand, our results indicate that the slower discounting becomes, the more certain an extortioner needs to be about an increasingly distant future: sufficient patience thus requires sufficient certainty. These findings illustrate the difficulties one can expect when attempting to exert strategic influence in the real world and provide new insights for decision-making experiments in more controlled environments. From a more technical point of view, our extension to time-varying strategies that is found in the Supplementary Information section 2, provides a novel perspective for the study of reciprocity in changing environments43.

In this paper, we interpreted the beta distribution as a common uncertain belief in the discount factor or continuation probability which is a rather restricting assumption. However, we believe arguments can be made for interpreting the beta distribution as an approximation of the distribution of discount factors in a large group of individuals21,44. In this case, (1) can be seen as a weighted average discounting function used in collaborative decisions45,46. In this context, our framework can be used to theoretically study the strategic behaviour of groups making collective decisions and how the group composition can affect their cooperative behaviour.

Regardless of the interpretation, our work shows that strategic efforts to solve social dilemmas must be adjusted to the uncertainty in the valuation of the future, because only then can strategic influence help to solve today’s societal concerns.

References

Green, L. & Myerson, J. A discounting framework for choice with delayed and probabilistic rewards. Psychol. Bull. 130, 769–792 (2004).

Sozou, P. D. On hyperbolic discounting and uncertain hazard rates. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 265, 2015–2020 (1998).

Keeney, R. L. & Raiffa, H. Decisions with Multiple Objectives: Preferences and Value Trade-offs (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1993).

Myerson, J., Green, L., Hanson, J. S., Holt, D. D. & Estle, S. J. Discounting delayed and probabilistic rewards: processes and traits. J. Econ. Psychol. 24, 619–635 (2003).

Jones, B. A. & Rachlin, H. Delay, probability, and social discounting in a public goods game. J. Exp. Anal. Behav. 91, 61–73 (2009).

Dreber, A., Fudenberg, D. & Rand, D. G. Who cooperates in repeated games: the role of altruism, inequity aversion, and demographics. J. Econ. Behav. Org. 98, 41–55 (2014).

Hilbe, C., Röhl, T. & Milinski, M. Extortion subdues human players but is finally punished in the prisoners dilemma. Nat. Commun. 5, 3976 (2014).

Hilbe, C., Chatterjee, K. & Nowak, M. A. Partners and rivals in direct reciprocity. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2, 469–477 (2018).

Stephens, D. W., McLinn, C. M. & Stevens, J. R. Discounting and reciprocity in an iterated prisoners dilemma. Science 298, 2216–2218 (2002).

Harris, A. C. & Madden, G. J. Delay discounting and performance on the prisoners dilemma game. The Psychological Record 52, 429–440 (2002).

Locey, M. L. & Rachlin, H. Temporal dynamics of cooperation. J. Behav. Decis. Mak. 25, 257–263 (2012).

Gutiérrez-Roig, M., Gracia-Lázaro, C., Perelló, J., Moreno, Y. & Sánchez, A. Transition from reciprocal cooperation to persistent behaviour in social dilemmas at the end of adolescence. Nat. Commun. 5, 4362 (2014).

Green, L., Myerson, J. & Ostaszewski, P. Discounting of delayed rewards across the life span: age differences in individual discounting functions. Behav. Process. 46, 89–96 (1999).

Charness, G. & Villeval, M.-C. Cooperation and competition in intergenerational experiments in the field and the laboratory. Am. Econ. Rev. 99, 956–78 (2009).

Jacquet, J. et al. Intra-and intergenerational discounting in the climate game. Nat. Clim. Change 3, 1025–1028 (2013).

Hauser, O. P., Rand, D. G., Peysakhovich, A. & Nowak, M. A. Cooperating with the future. Nature 511, 220–223 (2014).

Weitzman, M. L. Climate change: insurance for a warming planet. Nature 467, 784–785 (2010).

Rachlin, H., Raineri, A. & Cross, D. Subjective probability and delay. J. Exp. Anal. Behav. 55, 233–244 (1991).

Ostaszewski, P., Green, L. & Myerson, J. Effects of inflation on the subjective value of delayed and probabilistic rewards. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 5, 324–333 (1998).

Green, L., Fry, A. F. & Myerson, J. Discounting of delayed rewards: a life-span comparison. Psychol. Sci. 5, 33–36 (1994).

Weitzman, M. L. Gamma discounting. Am. Econ. Rev. 91, 260–271 (2001).

Karp, L. Global warming and hyperbolic discounting. J. Public Econ. 89, 261–282 (2005).

Weitzman, M. L. Why the far-distant future should be discounted at its lowest possible rate. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 36, 201–208 (1998).

Press, W. H. & Dyson, F. J. Iterated prisoners dilemma contains strategies that dominate any evolutionary opponent. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 109, 10409–10413 (2012).

Hilbe, C., Wu, B., Traulsen, A. & Nowak, M. A. Cooperation and control in multiplayer social dilemmas. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 111, 16425–16430 (2014).

Wang, Z., Zhou, Y., Lien, J. W., Zheng, J. & Xu, B. Extortion can outperform generosity in the iterated prisoners dilemma. Nat. Commun. 7, 11125 (2016).

Delton, A. W., Krasnow, M. M., Cosmides, L. & Tooby, J. Evolution of direct reciprocity under uncertainty can explain human generosity in one-shot encounters. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 108, 13335–13340 (2011).

Rand, D. G. & Nowak, M. A. Human cooperation. Trends Cognit. Sci. 17, 413–425 (2013).

Hardin, G. The tragedy of the commons. Science 162, 1243–1248 (1968).

Gokhale, C. S. & Traulsen, A. Evolutionary games in the multiverse. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 107, 5500–5504 (2010).

van Veelen, M. & Nowak, M. A. Multi-player games on the cycle. J. Theor. Biol. 292, 116–128 (2012).

Kerr, B., Godfrey-Smith, P. & Feldman, M. W. What is altruism?. Trends Ecol. Evolut. 19, 135–140 (2004).

Skyrms, B. The Stag Hunt and the Evolution of Social Structure (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2004).

Fudenberg, D. & Tirole, J. Game Theory (MIT Press, Cambridge, 1991).

Hilbe, C., Traulsen, A. & Sigmund, K. Partners or rivals? Strategies for the iterated prisoners dilemma. Games Econ. Behav. 92, 41–52 (2015).

Ainslie, G. Picoeconomics: The Strategic Interaction of Successive Motivational States Within the Person (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1992).

Van den Bos, W. & McClure, S. M. Towards a general model of temporal discounting. J. Exp. Anal. Behav. 99, 58–73 (2013).

MacKay, D. J. & Mac, Kay D. J. Information Theory, Inference and Learning Algorithms (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2003).

Jøsang, A. A logic for uncertain probabilities. Int. J. Uncertain. Fuzziness Knowl. Based Syst. 9, 279–311 (2001).

Stewart, A. J. & Plotkin, J. B. From extortion to generosity, evolution in the iterated prisoners dilemma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 110, 15348–15353 (2013).

Hilbe, C., Wu, B., Traulsen, A. & Nowak, M. A. Evolutionary performance of zero-determinant strategies in multiplayer games. J. Theor. Biol. 374, 115–124 (2015).

Murnighan, J. K. & Roth, A. E. Expecting continued play in prisoners dilemma games: a test of several models. J. Confl. Resolution 27, 279–300 (1983).

Hilbe, C., Šimsa, Š, Chatterjee, K. & Nowak, M. A. Evolution of cooperation in stochastic games. Nature 559, 246 (2018).

Myerson, J., Green, L. & Warusawitharana, M. Area under the curve as a measure of discounting. J. Exp. Anal. Behav. 76, 235–243 (2001).

Bixter, M. T., Trimber, E. M. & Luhmann, C. C. Are intertemporal preferences contagious? Evidence from collaborative decision making. Memory Cognit. 45, 837–851 (2017).

Tsuruta, M. & Inukai, K. How are individual time preferences aggregated in groups? A laboratory experiment on intertemporal group decision-making. Front. Appl. Math. Stat. 4, 43 (2018).

Acknowledgements

The work was supported in part by the European Research Council (ERC-CoG-771687) and the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO-vidi-14134).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.G. designed the research; A.G and M.C. performed the research and wrote the paper. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Govaert, A., Cao, M. Strategically influencing an uncertain future. Sci Rep 10, 12169 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-69006-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-69006-x

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.