Abstract

Vitamin B12 (B12) is a micronutrient essential for one-carbon (1C) metabolism. B12 deficiency disturbs the 1C cycle and alters DNA methylation which is vital for most metabolic processes. Studies show that B12 deficiency may be associated with obesity, insulin resistance and gestational diabetes; and with obesity in child-bearing women. We therefore hypothesised that the associations between B12 deficiency, BMI and the metabolic risk could be mediated through altered 1C metabolites in early pregnancy. We explored these associations in two different early pregnancy cohorts in the UK (cohort 1; n = 244 and cohort 2; n = 60) with anthropometric data at 10–12 weeks and plasma/serum sampling at 16–18 weeks. B12, folate, total homocysteine (tHcy), methionine, MMA, metabolites of 1C metabolism (SAM, SAH) and anthropometry were measured. B12 deficiency (< 150 pmol/l) in early pregnancy was 23% in cohort 1 and 18% in cohort 2. Regression analysis after adjusting for likely confounders showed that B12 was independently and negatively associated with BMI (Cohort 1: β = − 0.260, 95% CI (− 0.440, − 0.079), p = 0.005, Cohort 2: (β = − 0.220, 95% CI (− 0.424, − 0.016), p = 0.036) and positively with HDL cholesterol (HDL-C) (β = 0.442, 95% CI (0.011,0.873), p = 0.045). We found that methionine (β = − 0.656, 95% CI (− 0.900, − 0.412), p < 0.0001) and SAH (β = 0.371, 95% CI (0.071, 0.672), p = 0.017) were independently associated with triglycerides. Low B12 status and alteration in metabolites in 1C metabolism are common in UK women in early pregnancy and are independently associated with maternal obesity and dyslipidaemia. Therefore, we suggest B12 monitoring in women during peri-conceptional period and future studies on the pathophysiological relationship between changes in 1C metabolites and its association with maternal and fetal outcomes on larger cohorts. This in turn may offer potential to reduce the metabolic risk in pregnant women and their offspring.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The rise in obesity is a global challenge and is rapidly increasing in reproductive age. This influences obesity and increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes during pregnancy, which reinforces the risk to childhood obesity and other non-communicable diseases in adult life1. It is known that maternal macronutrients influence obesity, but emerging evidence suggest micronutrient deficiency such as vitamin B12, could play a role in adipogenesis2,3. B12 is involved in 1C metabolism and supplies the methyl groups required for the DNA methylation, which is key for maternal health and optimal fetal growth and development. Deficiency in B12 alters the levels of total homocysteine (tHcy), methionine, methylmalonic acid (MMA) and metabolites of 1C cycle including S-adenosyl methionine (SAM) and S-adenosyl homocysteine (SAH), which is associated with various adverse pregnancy outcomes and cardiovascular complications4. Since epigenetic modifications play a major role on the pathogenesis of many disease states, recent research predicts that metabolites of 1C metabolism might have an intermediate effect in adverse metabolic outcomes5.

Several observational and epidemiological studies have shown that low B12 is associated with high BMI6, insulin resistance (IR)7, increasing severity of glucose tolerance8 and adverse lipid profiles in type 2 diabetes (T2D)9. Supporting this, a recent Mendelian Randomization study10 reported a possible causal relationship between B12 and fasting glucose and β-cell function. A series of studies during pregnancy in both South Asian11,12 and Caucasian6 have shown association of low B12 with obesity, IR and higher risk of GDM. In children and adolescents, increase in BMI13 and IR14 have been associated with low B12 levels. Furthermore, studies in early pregnancy have focussed on association between lower maternal micronutrient status (B12, folate, iron) with pre-pregnancy overweight and obesity in mothers15,16,17, with lower micronutrients in low-birth weight infants18 and with higher BMI and heart rate in children at age 5–619. Our in vitro studies have shown that B12 deficiency in adipocytes altered DNA methylation levels2 of the transcription factors of lipid regulation2 and the adipose derived miRNAs targeting IR3 thereby suggesting that B12 deficiency dysregulates epigenetic mechanisms.

Though several studies have found an association between B12 and metabolic risk, there are very few studies on 1C metabolites in pregnancy. Our pilot study showed association of 1C metabolites with low B12 and increased triglycerides20. A study in Brazil reported that lower maternal B12 concentration is associated with higher tHcy and lower SAM:SAH in newborns21. A Danish cross-sectional study in non-pregnant adults found that plasma 1C metabolites positively associated with higher risk of metabolic dysfunction22. In addition, a recent study of mother-infant dyads identified changes in methylation patterns in 993 CpG sites, which were related to altered 1C metabolite indices over pregnancy, thereby suggesting the impact of different 1C metabolites on regulation of DNA methylation at multiple sites23. This evidence supports that altered 1C metabolites, adversely affect epigenetic mechanisms and metabolic health of both mother and offspring. Since underlying nutritional status influences the predictors of DNA methylation, studying these 1C biomarkers at early pregnancy, the embryonic development period involving complex epigenetic remodelling will extend our understanding of association of 1C metabolites with metabolic risk.

Furthermore, understanding the early life contributors will be crucial for delineating the risk factors and their mechanisms leading to maternal obesity and metabolic risk. This may inform targeted implementation of obesity prevention in early pregnancy. We therefore hypothesise that the associations between B12 deficiency, BMI and the metabolic risk could be mediated through altered 1C metabolites in early pregnancy. Our current study investigated the prevalence of B12 deficiency and the associated changes in tHcy, methionine, MMA and metabolites of 1C metabolism (SAM and SAH) during early pregnancy. We also report their association with maternal obesity and dyslipidemia.

Research design and methods

Study population

Cohort 1

The study was conducted in George Eliot Hospital, Nuneaton, UK. Pregnant women (n = 244) who met the inclusion criteria of women with singleton pregnancy, free of chronic diseases or any other pregnancy complications and delivered full-term (37–42 weeks of gestation) healthy infant were included in this study. All pregnant women provided blood samples between 16 and 18 weeks of their pregnancy as part of their routine care. Data on age, weight, smoking, alcohol, parity and socioeconomic status were obtained from pregnancy records. The samples were stored at − 80 °C and later analysed for metabolites. All methods were carried out in accordance with the approved ethical guidelines. The study was approved by the NHS Research Ethics Committee (12/LO/0239) and all subjects gave written informed consent.

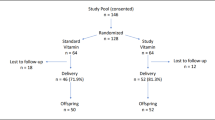

Cohort 2

This study was conducted in the Antenatal Metabolic Clinic, Simpson’s Centre for Reproductive Health, Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh. Pregnant women (n = 60) identified during their first community midwifery visit having a BMI ≥ 40 and lean controls with BMI ≤ 25 were invited to participate in a prospective cohort study from 2008 to 201224. Information on age, parity, smoking status and social and demographic data were collected. The main exclusions were pre-existing diabetes and major anomalies. Women who developed GDM or did not undergo an oral glucose tolerance test at 24–28 weeks’ gestation or developed pre-eclampsia or delivered < 37 weeks’ gestation were excluded from analyses. Venous blood samples were collected at 16–18 weeks’ gestation after an overnight fast and samples were stored at − 80 °C for later determination of metabolites. All research methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. Ethical approval was obtained from the Lothian NHS Research Ethics Committee, and all subjects gave informed written consent (REC reference number 08/S1101/39)25.

Analytical determinations

Serum B12 and folate were determined by electro-chemiluminescent immunoassay using a Roche Cobas immunoassay analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, UK). We used 150–660 pmol/l for serum B12 and 6–37 nmol/l for serum folate as normal ranges, respectively. The inter-assay coefficient of variations for B12 and folate were 3.9% and 3.7%, respectively26. B12 deficiency was defined as B12 levels below 150 pmol/l, borderline B12 deficiency as 150–220 pmol/l and folate deficiency as below 6 nmol/l. Excess folate is defined as > 37 nmol/l (upper limit of detection by the assay). Measurement of tHcy, methionine, MMA and metabolites of 1C metabolism (SAM and SAH) were determined in plasma by stable isotopic dilution analysis liquid chromatography using an API 6,500 QTrap tandem mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems, UK)20. Glucose concentrations were measured by a hexokinase method (Randox Laboratories, Co. Antrim, UK), total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol (HDL-C), (Olympus Diagnostics, Watford, UK) and triglycerides (Alpha Laboratories, Eastleigh, UK) were measured by colorimetric methods.

Statistical analysis

Continuous data are reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Categorical data are reported in percentages. The distributions of the data such as B12, folate, tHcy, MMA, methionine, SAM, SAH, cholesterol, triglycerides and HDL-C were skewed; these data were log-transformed before analyses. Student’s t-test was used for comparison of groups. Pearson’s correlation was used to compare the variables. Variables that showed significant associations were included as independent variables in the multiple linear regression analyses and adjusted for confounders such as age, smoking, alcohol, parity, BMI, B12, folate, tHcy, MMA, methionine, SAM and SAH. To facilitate comparison, dependent and independent variables were converted into standard deviation scores (SDS). The data are presented as SDS change in dependent variable per SDS change in BMI, triglycerides and HDL-C. All tests were two-sided, and p-values of < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics version 21 (IBM Corp, NY, USA)26.

Results

Baseline characteristics

The clinical characteristics of pregnant women from two cohorts are shown in Table 1. All women were recruited in early pregnancy at 16–18 weeks. Their booking BMI were collected at 10–12 weeks of gestation. Significant proportion of women were obese and reported higher rates of smoking and alcohol intake during pregnancy (Table 1). We found the rates of B12 and borderline B12 deficiency were 23 and 36% in cohort 1 and 18 and 43% in cohort 2, respectively. However, we did not observe any folate deficiency in either of these cohorts (Table 1).

Association of B12 with metabolic risk factors in early pregnancy

In both cohorts, B12 was negatively correlated with BMI, tHcy and MMA; and positively correlated with SAM/SAH (Fig. 1A–H). In addition, in cohort 2, there was evidence of association of B12 with lipid parameters such as negative correlation with triglycerides and positive correlation with HDL-C (Fig. 2A–B). To further examine the independent association of B12 and 1C metabolites with these risk factors, multiple regression analyses were carried out including the potential cofounders such as age, smoking, alcohol, parity, and socio-economic status. We found that B12 remained independently associated with BMI (Cohort 1: β = − 0.260, 95% CI (− 0.440, − 0.079), p = 0.005, Cohort 2: (β = − 0.220, 95% CI (− 0.424, − 0.016), p = 0.036) when adjusted for all co-variates (Table 2).

*Log transformed for statistical comparisons. Correlation between B12 and (A) BMI in cohort 1, (B) BMI in cohort 2, (C) Homocysteine in cohort 1, (D) Homocysteine in cohort 2, (E) MMA in cohort 1, (F) MMA in cohort 2, (G) SAM:SAH in cohort 1, (H) SAM:SAH in cohort 2. Cohort 1: n = 240; cohort 2: n = 60.

In addition, in cohort 2 (Table 3), in the fully adjusted model, B12 showed independent, positive associations with HDL-C (β = 0.442, 95% CI (0.011, 0.873), p = 0.045). We also found that low maternal B12 during early pregnancy was associated with higher triglycerides in the unadjusted model, but after adjustment for all potential confounders, this association was not significant. However, we found that methionine (β = − 0.656, 95% CI − 0.900, − 0.412, p < 0.0001) and SAH (β = 0.371, 95% CI: 0.071, 0.672, p = 0.017) were associated significantly with higher triglycerides after adjusting for the confounders. This implies that higher triglycerides in B12 deficient women during early pregnancy could be mediated by these metabolites.

Discussion

Our study involving two cohorts with Caucasian women at early pregnancy from UK had three main findings. Firstly, vitamin B12 deficiency rates were 23% in cohort 1 and 18% in cohort 2. Secondly, low B12 level was associated with higher BMI and lower HDL-C. Thirdly, we found that lower levels of methionine and higher levels of SAH associated with higher triglycerides in these women at early pregnancy.

The prevalence of B12 deficiency in early pregnancy has been reported in very few studies. A recent systematic review showed that B12 deficiency were 21%, 19%, and 29% in the first, second and third trimesters, respectively27. We found similar rates of deficiency of B12 (cohort 1–23% & cohort 2–18%) in our cohorts in early pregnancy. The regression analysis in cohort 1, after correcting for multiple confounders, we found that B12 is independently associated with BMI whereas in cohort 2, in addition to B12, social deprivation was also associated with BMI. The association between BMI and B12 has been shown in other studies in pregnant women15,16,17 but also in adolescents14 and in women of childbearing age28. In addition, B12 deficiency may be causally related to dysglycaemia9. It is therefore conceivable that if women with higher prevalence of B12 deficiency enter pregnancy, it may predispose them to greater risk of obesity, dyslipidemia and hyperglycaemia. However, longitudinal studies are required to investigate whether low B12 in early pregnancy increases the risk of incident GDM.

In a recent meta-analysis, we reported that maternal low HDL-C and high triglycerides at different trimesters of pregnancy are associated with higher birthweight, higher risk of large for gestational age and macrosomia29. The present study showed that lower B12 was associated with lower HDL-C levels in early pregnancy. In our previous study of pregnant women at third trimester a similar association was seen26. Consistent to this, Knight et al.6 showed this relationship in women at 28 weeks of gestation in the UK and Saraswathy et al.30 in a non-pregnant adult population in India. In addition, our mechanistic studies in adipocytes indicate that in low B12 status, hypomethylation of the lipid transcription factors (SREBF1 and LDLR)2 and alteration of miRNAs3 could adversely regulate the adipogenic and lipogenic genes and promote dyslipidaemia.

We also observed that in addition to the effect of B12 deficiency on lipid regulation, metabolites such as lower methionine and higher SAH were associated with higher triglycerides. This was similar to our previous observation in a small study of 30 pregnant women in early pregnancy, where the tHcy and 1C metabolites (SAM, SAM:SAH) were independently associated with triglycerides20. A study in Netherlands in women of reproductive age, found that BMI was the strongest determinant of SAM and SAH concentrations31. Lind et al. showed in people with the metabolic syndrome, the 1C metabolites were determinants of markers of adiposity such as BMI, body fat percentage and IR22. Plasma SAH has been shown to be better indicator of cardiovascular disease than tHcy32 and in vitro models have shown that elevated SAH adversely altered adipocyte function and altered methylation33. In vascular disease, global DNA methylation was altered with a concomitant increase in plasma tHcy and SAH34. Of further interest, a recent study by Knight et al. demonstrated that five out of thirteen 1C metabolites changed over pregnancy and these metabolites were associated with altered methylation levels of genes involved in neuronal and developmental process in both maternal and cord blood23. These findings add to the evidence that alteration in the indices of 1C metabolism in B12 deficient status could change the methylation potential, mediate the epigenetic modifications and contribute to adverse lipid levels and metabolic outcomes. Thus, circulating levels of indices of 1C metabolism could be used as a surrogate for cellular level methylation capacity in early pregnancy. As the biomarkers of cellular methylation are related to health and disease and influenced by micronutrients, it would therefore be of interest to further study this hypothesis in human trials or animal studies to show whether B-vitamins supplementation in peri-conceptional period reduces metabolic risk of the offspring by altering these methylation biomarkers.

The strengths of this study are that we included two cohorts of pregnant women from UK at 16–18 weeks of gestation. Detailed information of lifestyle, socio-economic status and methylation biomarkers were available for both the cohorts, which allowed to control for multiple potential confounders. The rate of B12 deficiency and the factors associated with obesity in the two settings increases the generalizability of findings. However, we acknowledge the following limitations. This study is observational in a single time point, so causality cannot be established. The lack of associations observed in other indices of 1C metabolism may well be due to our sample size and hence future investigations should include larger sample size. We did not have lipid levels or holo-transcobalamin levels in the first cohort. However, the independent associations seen with B12 and BMI in both the cohorts as well as the associations with B12/methionine/SAH and HDL-C/triglyceride levels despite the smaller size of cohort 2, warrants further investigation in larger studies. Finally, our study focussed only on some of the indices of the methionine cycle (and serum folate). Future studies measuring the entire 1C metabolite pathway (including the trans-sulphuration pathway) in early pregnancy, may provide more insights into cellular methylation potential and other epigenetic mechanisms.

In summary, our novel study highlighted that underlying nutritional (B12) status is an effective modifier of some of the 1C metabolites in early pregnancy. B12 deficiency in early pregnancy is adversely associated with altered level of 1C metabolites, maternal obesity and dyslipidaemia. These findings may have vital implications for pregnant women and their offspring, especially if they are overweight and obese. Out study suggests that assessment of B12 levels for women planning pregnancy may be worthwhile. Future investigations focusing on metabolites involved in 1C cycle associated with maternal and fetal outcomes is warranted for targeted intervention and obesity prevention in both mother and offspring.

Abbreviations

- 1CM:

-

One-carbon metabolism

- B12:

-

Vitamin B12

- GDM:

-

Gestational diabetes

- tHcy:

-

Total homocysteine

- IR:

-

Insulin resistance

- MMA:

-

Methylmalonic acid

- SAH:

-

S-adenosyl homocysteine

- SAM:

-

S-adenosyl methionine

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SDS:

-

Standard deviation scores

- T2D:

-

Type 2 diabetes

References

Catalano, P. M. & Shankar, K. Obesity and pregnancy: mechanisms of short term and long term adverse consequences for mother and child. BMJ 356, j1 (2017).

Adaikalakoteswari, A. et al. Vitamin B12 insufficiency induces cholesterol biosynthesis by limiting s-adenosylmethionine and modulating the methylation of SREBF1 and LDLR genes. Clin Epigenetics 7, 14 (2015).

Adaikalakoteswari, A. et al. Low vitamin B12 in pregnancy is associated with adipose-derived circulating miRs targeting PPARγ and insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 102, 4200–4209 (2017).

Finer, S., Saravanan, P., Hitman, G. & Yajnik, C. The role of the one-carbon cycle in the developmental origins of Type 2 diabetes and obesity. Diabet Med 31, 263–272 (2014).

Van Winkle, L. J. & Ryznar, R. One-carbon metabolism regulates embryonic stem cell fate through epigenetic DNA and histone modifications: implications for transgenerational metabolic disorders in adults. Front Cell Dev Biol 7, 300 (2019).

Knight, B. A. et al. Lower circulating B12 is associated with higher obesity and insulin resistance during pregnancy in a non-diabetic white British population. PLoS ONE 10, e0135268 (2015).

Li, Z. et al. Folate and vitamin B12 status is associated with insulin resistance and metabolic syndrome in morbid obesity. Clin Nutr 37, 1700–1706 (2018).

Jayashri, R. et al. Prevalence of vitamin B12 deficiency in South Indians with different grades of glucose tolerance. Acta Diabetol 55, 1283–1293 (2018).

Adaikalakoteswari, A. et al. Vitamin B12 deficiency is associated with adverse lipid profile in Europeans and Indians with type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol 13, 129 (2014).

Moen, G., Qvigstad, E., Birkeland, K. I., Evans, D. M. & Sommer, C. Are serum concentrations of vitamin B-12 causally related to cardiometabolic risk factors and disease? A Mendelian randomization study. Am J Clin Nutr 108, 398–404 (2018).

Krishnaveni, G. V. et al. Low plasma vitamin B12 in pregnancy is associated with gestational “diabesity” and later diabetes. Diabetologia 52, 2350–2358 (2009).

Lai, J. S. et al. High folate and low vitamin B12 status during pregnancy is associated with gestational diabetes mellitus. Clin Nutr 37, 940–947 (2018).

Ozer, S., Sonmezgoz, E. & Demir, O. Negative correlation among vitamin B12 levels, obesity severity and metabolic syndrome in obese children: A case control study. J Pak Med Assoc 67, 1648–1653 (2017).

Ho, M. et al. Vitamin B12 in obese adolescents with clinical features of insulin resistance. Nutrients 6, 5611–5618 (2014).

Scholing, J. M., Olthof, M. R., Jonker, F. A. & Vrijkotte, T. G. Association between pre-pregnancy weight status and maternal micronutrient status in early pregnancy. Public Health Nutr 21, 2046–2055 (2018).

O’Malley, E. G. et al. Folate and vitamin B12 levels in early pregnancy and maternal obesity. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 231, 80–84 (2018).

Bjørke-Monsen, A. et al. Impact of pre-pregnancy BMI on B vitamin and inflammatory status in early pregnancy: an observational cohort study. Nutrients 8, 776 (2016).

Riaz, M. et al. Maternal nutrition during early pregnancy and cardiometabolic status of neonates at birth. J Diabetes Res 2018, 7382946 (2018).

Krikke, G. G. et al. Vitamin B12 and folate status in early pregnancy and cardiometabolic risk factors in the offspring at age 5–6 years: findings from the ABCD multi-ethnic birth cohort. BJOG 123, 384–392 (2016).

Adaikalakoteswari, A., Webster, C., Goljan, I. & Saravanan, P. Simultaneous detection of five one-carbon metabolites in plasma using stable isotope dilution liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 1012–1013, 186–192 (2016).

Guerra-Shinohara, E. M. et al. Low ratio of S-adenosylmethionine to S-adenosylhomocysteine is associated with vitamin deficiency in Brazilian pregnant women and newborns. Am J Clin Nutr 80, 1312–1321 (2004).

Lind, M. V. et al. One-carbon metabolism markers are associated with cardiometabolic risk factors. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 28, 402–410 (2018).

Knight, A. K. et al. Association between one-carbon metabolism indices and DNA methylation status in maternal and cord blood. Sci Rep 8, 16873 (2018).

Mohd-Shukri, N. A. et al. Health behaviours during pregnancy in women with very severe obesity. Nutrients 7, 8431–8443 (2015).

Forbes, S. et al. Convergence in insulin resistance between very severely obese and lean women at the end of pregnancy. Diabetologia 58, 2615–2626 (2015).

Adaikalakoteswari, A. et al. Low maternal vitamin B12 status is associated with lower cord blood HDL cholesterol in white Caucasians living in the UK. Nutrients 7, 2401–2414 (2015).

Sukumar, N. et al. Prevalence of vitamin B-12 insufficiency during pregnancy and its effect on offspring birth weight: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Clin Nutr 103, 1232–1251 (2016).

Sukumar, N., Adaikalakoteswari, A., Venkataraman, H., Maheswaran, H. & Saravanan, P. Vitamin B12 status in women of childbearing age in the UK and its relationship with national nutrient intake guidelines: results from two National Diet and Nutrition Surveys. BMJ Open 6, e011247 (2016).

Wang, J. et al. Gestational dyslipidaemia and adverse birthweight outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev 19, 1256–1268 (2018).

Saraswathy, K. N., Joshi, S., Yadav, S. & Garg, P. R. Metabolic distress in lipid & one carbon metabolic pathway through low vitamin B-12: a population based study from North India. Lipids Health Dis 17, 96 (2018).

van Driel, L. M. J. W. et al. Body mass index is an important determinant of methylation biomarkers in women of reproductive ages. J Nutr 139, 2315–2321 (2009).

Kerins, D. M., Koury, M. J., Capdevila, A., Rana, S. & Wagner, C. Plasma S-adenosylhomocysteine is a more sensitive indicator of cardiovascular disease than plasma homocysteine. Am J Clin Nutr 74, 723–729 (2001).

Ngo, S. et al. Elevated S-adenosylhomocysteine alters adipocyte functionality with corresponding changes in gene expression and associated epigenetic marks. Diabetes 63, 2273–2283 (2014).

Castro, R. et al. Increased homocysteine and S-adenosylhomocysteine concentrations and DNA hypomethylation in vascular disease. Clin Chem 49, 1292–1296 (2003).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the clinic staffs at George Eliot Hospital, the assistance of clinical research nurse (Mr Selvin Selvamoni), research coordinators (Mrs Amitha Gopinath and Mrs Karen Rouault) in supporting the recruitment of patients. The funding body did not have any input on the design, objectives or the analysis of the results. The study was supported by Diabetes Research Fund, George Eliot NHS trust, Nuneaton, UK. PS’s time was in part supported by different project funds from the Medical Research Council (MRC), UK (MR/N006232/1 and MR/J000094/1). We acknowledge the support of Tommy’s and the British Heart Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.A. and P.S. conceived the research question and study design. A.A. performed the 1C metabolite analysis, data collection, statistical analysis, data interpretation and drafted the manuscript. C.W.3 was involved in the recruitment of the pregnant women in Cohort 1 and sample collection. T.M. was involved in the recruitment of the pregnant women in Cohort 2 and sample collection. C.W.5 provided the LC–MS/MS facility for 1C determination. I.G. performed the sample processing and analysis of B12, folate and 1C metabolites and Y.W. provided support to the statistical analysis. R.R. provided the cohort 2. All authors contributed, revised and approved the final version of the manuscript for submission. P.S. and R.R. are the guarantor of this work and had full access to all the data presented in the study and takes full responsibility for the integrity and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third-party material in this article is included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Adaikalakoteswari, A., Wood, C., Mina, T.H. et al. Vitamin B12 deficiency and altered one-carbon metabolites in early pregnancy is associated with maternal obesity and dyslipidaemia. Sci Rep 10, 11066 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-68344-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-68344-0

This article is cited by

-

Periconceptional biomarkers for maternal obesity: a systematic review

Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders (2023)

-

Influence of maternal and paternal pre-conception overweight/obesity on offspring outcomes and strategies for prevention

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.