Abstract

Physical exercise has been shown to alter sensory functions, such as sensory detection or perceived pain. However, most contributing studies rely on the assessment of single thresholds, and a systematic testing of the sensory system is missing. This randomised, controlled cross-over study aims to determine the sensory phenotype of healthy young participants and to assess if sub-maximal endurance exercise can impact it. We investigated the effects of a single bout of sub-maximal running exercise (30 min at 80% heart rate reserve) compared to a resting control in 20 healthy participants. The sensory profile was assessed applying quantitative sensory testing (QST) according to the protocol of the German Research Network on Neuropathic Pain. QST comprises a broad spectrum of thermal and mechanical detection and pain thresholds. It was applied to the forehead of study participants prior and immediately after the intervention. Time between cross-over sessions was one week. Sub-maximal endurance exercise did not significantly alter thermal or mechanical sensory function (time × group analysis) in terms of detection and pain thresholds. The sensory phenotypes did not indicate any clinically meaningful deviation of sensory function. The alteration of sensory thresholds needs to be carefully interpreted, and only systematic testing allows an improved understanding of mechanism. In this context, sub-maximal endurance exercise is not followed by a change of thermal and mechanical sensory function at the forehead in healthy volunteers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Exercise-induced changes of the somatosensory profile have led to controversial discussions, in particular with regards to their effect on pain. Exercise has been shown to induce hypoalgesia in healthy subjects1, however, it can also induce hyperalgesia in certain chronic diseases or following exertion2. Its effects in people with clinical pain are rather variable. In patients with neuropathic pain, exercise is considered to improve nerve function, reduce pain and other sensory dysfunction, and improve static and dynamic functional mobility3. However, in patients with musculoskeletal pain, manual therapies on stability failed to achieve a significant pain reduction4. A recent systematic review suggests an association between psychosocial factors and exercise-induced hypoalgesia in healthy subjects, and in patients with musculoskeletal pain5. This is further supported by a proposed central mechanism underlying these two phenomena, such as the increased activation of NMDA receptors in pain-modulating areas6.

Exercise-induced hypoalgesia, i.e. pain reduction, can be achieved by both aerobic and resistance training, of which the latter achieves larger mean effect sizes7. Aerobic exercise is more likely to induce generalised hypoalgesia, whereas resistance exercise is related to locoregional effect sites1. Higher aerobic intensities (200 W or 60–75% oxygen uptake) appear more effective in mediating hypoalgesia. Isometric exercise was shown to decrease the intensity of experimental pain at loads around 25% of maximum voluntary contraction8. Physiologic research points to the activation of the endogenous opioid9 and cannabinoid system10 as a cardinal mechanism of exercise-induced hypoalgesia.

Exercise-induced hyperalgesia, the phenomenon of increased pain perception following exercise, is more likely to be observed in patients with conditions such as myalgic encephalomyelitis2, chronic fatigue syndrome2,11, fibromyalgia12, or painful diabetic neuropathy13. It has been suggested that a different response of the immune system—which is already weakened in certain chronic diseases—partially contributes to this phenomenon. The increased sensitivity to exercise in musculoskeletal pain has also been linked to psychological factors such as catastrophizing and inability to disengage, as well as other processes related to the central sensitisation of pain14.

The current literature’s main limitations are of methodologic nature, as many studies fail to adhere to current recommendations on exercise doses, or accurately report the applied exercise loads1. In addition, many studies base their findings on the assessment of single sensory thresholds, thereby decoding only parts of the complex physiologic network underlying sensory phenotypes1,7,15. Finally, exercise-induced hypoalgesia is widely defined as decreased sensitivity to externally induced painful stimuli7, therefore assessing an experimental instead of a clinical setting.

The aim of this present study was to determine the immediate, exercise-induced effects on sensory function. Taking into account the aforementioned observations, we designed our study to allow a systematic description of the pattern of sensory loss and gain caused by a single bout of aerobic exercise, which may reflect the underlying physiology15. Quantitative sensory testing (QST) has been established as the clinical standard to assess a multitude of sensory thresholds, by applying predetermined physical stimuli16, reliably describing an individual’s sensory profile, and identifying sensory deficits or hyperphenomena.

Methods

Study design

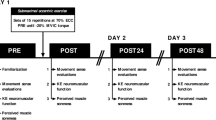

A randomised, controlled cross-over study investigating the effects of a vigorous exercise intervention on sensory thresholds in healthy adults. The study has been approved by the Local Ethics Committee FB05 of the Goethe University of Frankfurt, Germany (reference 2017-028) and is in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (Version Fortaleza 2012). Inclusion criteria were volunteers between age 18 and 30. Exclusion criteria were pregnancy or lactation, continuous use of analgesics and/or intake within 24 h prior to the study, acute or chronic pain, sensory disorders, and severe illness affecting the quality of life17.

Written informed consent was obtained by all participants. After enrolment, participants were subsequently randomised to either Group 1 or Group 2, using an online-based randomisation software stratifying for gender18. Groups differed with regards to the sequence of the intervention (vigorous exercise) and control setting:

Group 1: Assessment–Exercise–Assessment–Wash Out (1 week)–Assessment–Control–Assessment.

Group 2: Assessment–Control–Assessment–Wash Out (1 week)–Assessment–Exercise–Assessment.

Participants had to perform 30 min of running exercise on a track. The individual intensity was calculated applying the Karvonen formula (80% heart rate reserve) and monitored by a pulse watch (Polar S810®, Kempele, Finland). For the control procedure, participants were sitting for 30 min, with continuous heart rate monitoring to exclude any physical workload.

Sensory thresholds were assessed using the QST method at baseline (i.e. prior to) and immediately following either intervention or control. QST consists of 7 tests measuring 13 parameters in order to assess and quantify the perception of temperature, touch, pain, pressure, and vibration. We could previously demonstrate that the adherence of the proposed test order of QST is relevant in interpreting the obtained results19. The detailed QST protocol including reference data is reported elsewhere16.

Thermal Testing comprising cold and warm detection thresholds (CDT, WDT), paradoxical heat sensations (PHS) during the thermal sensory limen procedure (TSL) of alternating warm and cold stimuli and cold and heat pain thresholds (CPT, HPT).

Mechanical Testing comprising mechanical detection thresholds (MDT), mechanical pain thresholds (MPT), mechanical pain sensitivity (MPS), dynamic mechanical allodynia (DMA), the wind-up ratio (WUR), vibration detection thresholds (VDT) and pressure pain thresholds (PPT).

QST was performed at the forehead.

Sample size estimation

The sample size was estimated based on a previous study suggesting an effects size of 0.65 for the change in pressure pain threshold at the forehead20. Applying an α of 0.05, and a power of 0.95, we calculated a total sample size of n = 40, taking into account a 20% drop-out ratio. Applying a cross-over study design, n = 20 participants were needed.

Statistics

QST data were analysed as described by Rolke et al.16, i.e. some of the data were log-transformed in order to achieve normally distributed data. Consequently, data were compared using a two-way analysis of variance for repeated measures (time × group 2 × 2).We calculated the mean differences for all parameters, which were analysed by paired Students’ t test. Finally, for comparisons of the QST data profile following exercise or rest with the baseline data, all parameters were Z-transformed by using the equation:

The Z-score values were presented with values above “0” indicating a gain of function and below “0” indicating a loss of function16.

Results

Twenty healthy volunteers (female n = 10, age 25 ± 2.3 years, weight 69.8 ± 13.5 kg, height 174.3 ± 9.4 cm) participated in this study, and no drop-outs occurred. Heart rate at rest was 56.65 ± 8.03 min−1, and HRR80 was calculated at 160.75 ± 3.34 min−1. During exercise, the mean heart rate was 160.19 ± 7.5 min−1, and during control (rest) 56.49 ± 7.12 min−1. Exercise intensity was rated 12.9 ± 1.74 (“somewhat hard”) on a Borg-scale.

Wash-out between sessions was successful, with equal baseline thresholds prior to both sessions.

Time × group analysis (2 × 2) could not detect any significant differences between groups over time (p > 0.05; see Table 1) 17.

There was also no statistically significant difference detected when analysing difference scores (p > 0.05; see Table 2)17. Z-profiles indicated no differences between groups, nor did we detect deviations larger than the twofold standard deviation within our study group, which would indicate pathologic findings (see Fig. 1).

Z-profile of sensory thresholds following intervention (open circles) or control (black squares). Z-score values reflect the patient’s sensitivity for each parameter compared to the group mean at baseline. Z-values above “0” indicate a gain of function when the patient is more sensitive to the tested stimuli compared with controls, while Z-scores below “0” indicate a loss of function referring to a lower sensitivity of the patient16. CDT cold detection threshold, WDT warm detection threshold, TSL thermal sensory limen, CPT cold pain threshold, HPT heat pain threshold, PHS paradoxical heat sensation, MDT mechanical detection threshold, MPT mechanical pain threshold, MPS mechanical pain sensitivity, WUR wind up ratio, VDT vibration detection threshold, PPT pressure pain threshold.

In an exploratory analysis, we were able to detect within group differences for thermal thresholds in the intervention group, with CDT (paired t test, p = 0.002), WDT (p < 0.01), and TSL (p = 0.014). We also found gender differences for the change of TSL in the intervention group (female − 0.48 ± 0.93 °C vs. male − 0.46 ± 1.18 °C; p = 0.034) and for the change of WUR in the control group (female 0.01 ± 2.52 vs. male − 2.10 ± 3.56; p = 0.034). Sensory thresholds at baseline did not differ between genders. We did not observe side effects.

Discussion

In this study, a homogeneous group of physically active students performed a submaximal endurance exercise and a control intervention. There were no differences in systematically assessed sensory thresholds pre- and post intervention. A 30-min long submaximal physical workload did neither result in exercise-induced hyperalgesia nor hypoalgesia.

Our data are in contrast with some previous studies, which suggested exercise-induced alterations of sensory thresholds. With regards to thermal thresholds, there are only a few studies which investigated the impact of exercise interventions. Some have proposed that exercise can mediate a change of thermal detection21 and thermal pain thresholds22. Our data (Z-profiles, Fig. 1) do not support a hypothesis of opposite trends regarding either loss or gain of function between control and exercise. All observed changes are less than one standard deviation, with changes above two standard deviations having been defined being of pathologic character16, and are thus of reduced clinical significance.

QST is considered the clinical gold standard in exploring pain pathologies, therefore we find the assessment of sensory profiles by applying the QST protocol as a methodological strength of our findings15,16. Other research groups have used different protocols, such as segmental and plurisegmental exercise-induced hypoalgesia defined as using normalized PPTs during static muscle contractions23. This approach is reliable to assess pressure algometry long-term24, and can be best understood as a comprehensive tool to assess exercise-induced hypoalgesia. Koltyn et al. assessed thermal measures besides detecting the PPT10. However, their approach deviated from the original QST protocol, as only contact heat evoked potentials have been applied as heat stimuli. This is known to evoke Type IV (C-fiber) temporal pain summation. The same group also focussed on molecular parameters of pain, especially the involvement of endocannabinoid markers10,25. Furthermore, conditioned pain modulation has been proposed to examine central pain inhibitory processing26. This laboratory test examines changes in sensitivity to an electrical pain stimulus applied to one part of body and after exposure to a conditioning cold pain stimulus applied to a distant part of the body. Applying this method, a recent study could not detect changes in conditioned pain modulation when comparing resistance exercisers to healthy controls27. Finally, our results are in line with a study applying a more refined methodology including some QST measures that could show that prolonged muscular activation (contraction) of the sternocleidomastoid muscle did not alter cold detection or mechanical thresholds28.

The number of other studies investigating the effects of exercise on thermal thresholds is limited. In this context, submaximal isometric knee extensions are not sufficient to alter heat pain thresholds in healthy young men29. Eccentric plantar flexor exercise showed no effects on the heat pain threshold in asymptomatic individuals30, but participants showed some reduced heat temporal summation the following morning. This could be explained by reduced central processing of painful stimuli, and confirm a previous study, which showed a trend for lumbopelvic stabilization training to increase heat but not the cold pain thresholds31. To our knowledge, there is no study reporting the effects of endurance exercise on thermal thresholds. One prior study has reported pain thresholds assessed in endurance athletes versus strength athletes versus controls32. Based on thermal threshold changes, the authors suggest that endurance-based exercise is associated with improved pain inhibition, and strength-based exercise with reduced pain sensitivity. In general, athletes have shown decreased ratings in temporal summation of pain (see above)32. In our study, we assessed the wind-up ratio as the mechanical correlate for temporal summation, and found no direct effects of exercise. It is therefore possible that regular exercise, but not single bouts, can affect thermal sensitivity, if at all. In this context, another point of discussion is whether the observed gender-difference in wind-up, i.e. a ratio reduced by 2 points on tenfold scale in male participants, could be a sign for a different central mechanism of exercise-induced modulation of pain perception in male and female, or an incidental finding due to multiple testing.

The number of studies investigating the effects of exercise on mechanical thresholds is more robust. Our results do neither indicate signs of exercise-induced mechanical hypo-nor hyperalgesia. To our knowledge, there is no study showing alterations of mechanical detection thresholds. Interestingly, there is one single study which showed that pre-exercise massage increased the mechanical detection threshold33. Both, massage and threshold, were negatively associated with muscle performance in a subsequent isokinetic exercise33. It is therefore important to carefully distinguish Hypo-/hyperaesthesia (detection) and Hypo-/Hyperalgesia (pain). Pain thresholds, i.e. mechanical and pressure pain, have been related extensively to the occurrence of delayed onset muscle soreness and exercise-induced muscle damage. Both thresholds are negatively affected, this corresponds to an increased pain perception34. Hyperalgesia in muscles is physiologically linked to the increased excitability of high-threshold mechanosensitive nociceptors, with the pressure pain threshold being the most appropriate measure34. All studies of this type have an eccentric muscular load in common. Thus, eccentric strength training may be categorised mediating muscular mechanical hyperalgesia. With regards to endurance (aerobic) exercise, Naugle et al. calculated a pooled moderate effect size for hypoalgesic effects on different pain thresholds7. The authors included two studies dealing with single mechanical thresholds (pressure), and aerobic intensities between 50 to 75% of VO2max. On the one hand, this is strengthened by a recent study showing aerobic exercise (cycling at 60–70% HRR for 15 min) to reduce pressure pain sensitivity but not heat pain sensitivity35. On the other hand, this is in contrast to another study, showing aerobic exercise until exhaustion to mediate mechanical hyperalgesia20. Kruger et al. discuss the impact of the intensity of exercise to be a key factor in a u-shaped relationship between aerobic exercise and hypo- or hyperalgesia. In summary, exercise-induced hypoalgesia may occur on a level of aerobic intensity above 75% VO2max with a duration of more than 10 min20. The chosen intensity in our study (80% HRR) is likely equal to this proposed intensity36, and duration of the exercise was 30 min. Thus, our results do not support the thesis that single moderate to vigorous aerobic bouts automatically lead to an alteration of the somatosensory profile.

From a clinical point of view, none of the above mentioned studies questioned if the observed changes of thresholds were of clinical relevance. In the meta-analysis by Naugle7, there were two studies reporting an increased pressure pain threshold following aerobic exercise. In the first study, the mean threshold increase was approximately 0.45 kg/cm2 in healthy volunteers37. The second study did not assess the exact threshold, but the time a specific weight could be withstood38. Kruger et al. reported a threshold decrease by approximately 8 N, which is almost 0.8 kg/cm2. In our study, the difference in pressure pain threshold was − 4.85 kPa (approximately − 0.04 kg/cm2). To explore possible clinical implications from these studies, a conversion into Z-scores is a common statistical method that re-scales the observed changes on the normative distribution within the population (see Fig. 1). Data extracted from Meeus et al. suggest a Z-score of 0.16, Krugers data from Fig. 1 can be extrapolated to a Z-score of approximately 0.4, and our study reports a Z-score of − 0.04, all based on the respective study population. All studies have in common that the conversion into Z-scores would result in threshold changes that are far from being clinically relevant.

Limitations of the present study include variations of the outdoor climate during track exercise. We carefully chose comparable climatic conditions for all study subjects, and found similar baseline thresholds at both times of assessment, but cannot completely rule out if variations in weather may have influenced the measures. In addition, the QST measure lasts approximately 30-min16, assessing thermal thresholds first and mechanical thresholds thereafter. To our knowledge, the duration of observed hypo- or hyperalgesic effects after exercise is not yet clear. It is therefore possible that proposed hypoalgesic effects on mechanical thresholds had already become weaned off7. However, the QST method has been established as the gold standard to reliably assess sustainable effects of exercise on the somatosensory system15. A clinically important effect size of exercise on detection and pain thresholds would have been unmasked by QST and the statistical analysis. The chosen site of measure in our study, the forehead, was selected in accordance to the Kruger study20, in order to make a sample size estimation and to rule out methodological differences. To our knowledge there is not yet a predefined measure site to detect sensory changes among athletes. Due to the physiology of thermoregulation39, it is possible that the effects of exercise at the head are more likely to affect thermal than mechanical thresholds. In addition, we found the forehead to be appropriate, as we wanted to rule out effects caused by muscular soreness and/or damage at measure sites at the extremities34. Therefore we cannot rule out that sensory profiles would had been different at other parts of the body, which should consequently be subject to next studies.

Conclusion

In contrast to prior studies showing either exercise-induced hypoalgesia or hyperalgesia induced by aerobic exercise, our findings do not suggest that sub-maximal aerobic exercise alters the sensory profile at the forehead in healthy young and physically active participants. From a clinical point of view, our data suggest that previously reported sensory changes in healthy participants are of minor clinical significance. However, exercise as a therapy to treat pain in patients can be clinically meaningful. While previous studies assessed single sensory thresholds, we applied a comprehensive and standardised testing, allowing a more profound clinical analysis of descriptive findings. Further studies will be necessary to detect the impact of exercise intensity as well as the effect of exercise on other parts of the human body.

References

Rice, D. et al. Exercise-induced hypoalgesia in pain-free and chronic pain populations: state of the art and future directions. J. Pain 20, 1249–1266. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2019.03.005 (2019).

Polli, A. et al. Exercise-induce hyperalgesia, complement system and elastase activation in myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome—a secondary analysis of experimental comparative studies. Scand. J. Pain 19, 183–192. https://doi.org/10.1515/sjpain-2018-0075 (2019).

Dobson, J. L., McMillan, J. & Li, L. Benefits of exercise intervention in reducing neuropathic pain. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 8, 102. https://doi.org/10.3389/fncel.2014.00102 (2014).

Kendall, J. C., Vindigni, D., Polus, B. I., Azari, M. F. & Harman, S. C. Effects of manual therapies on stability in people with musculoskeletal pain: a systematic review. Chiropr. Man. Ther. 28, 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12998-020-0300-9 (2020).

Munneke, W., Ickmans, K. & Voogt, L. The association of psychosocial factors and exercise-induced hypoalgesia in healthy people and people with musculoskeletal pain: a systematic review. Pain Pract. https://doi.org/10.1111/papr.12894 (2020).

Lima, L. V., Abner, T. S. S. & Sluka, K. A. Does exercise increase or decrease pain? Central mechanisms underlying these two phenomena. J. Physiol. 595, 4141–4150. https://doi.org/10.1113/JP273355 (2017).

Naugle, K. M., Fillingim, R. B. & Riley, J. L. 3rd. A meta-analytic review of the hypoalgesic effects of exercise. J. Pain 13, 1139–1150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2012.09.006 (2012).

Hoeger Bement, M. K., Dicapo, J., Rasiarmos, R. & Hunter, S. K. Dose response of isometric contractions on pain perception in healthy adults. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 40, 1880–1889. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0b013e31817eeecc (2008).

Thorén, P., Floras, J. S., Hoffmann, P. & Seals, D. R. Endorphins and exercise: physiological mechanisms and clinical implications. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 22, 417–428 (1990).

Koltyn, K. F., Brellenthin, A. G., Cook, D. B., Sehgal, N. & Hillard, C. Mechanisms of exercise-induced hypoalgesia. J. Pain 15, 1294–1304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2014.09.006 (2014).

White, A. T. et al. Severity of symptom flare after moderate exercise is linked to cytokine activity in chronic fatigue syndrome. Psychophysiology 47, 615–624. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.2010.00978.x (2010).

Lannersten, L. & Kosek, E. Dysfunction of endogenous pain inhibition during exercise with painful muscles in patients with shoulder myalgia and fibromyalgia. Pain 151, 77–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2010.06.021 (2010).

Knauf, M. T. & Koltyn, K. F. Exercise-induced modulation of pain in adults with and without painful diabetic neuropathy. J. Pain 15, 656–663. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2014.02.008 (2014).

Wideman, T. H. et al. Increased sensitivity to physical activity among individuals with knee osteoarthritis: relation to pain outcomes, psychological factors, and responses to quantitative sensory testing. Pain 155, 703–711. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2013.12.028 (2014).

Sommer, C. Exploring pain pathophysiology in patients. Science 354, 588–592. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aaf8935 (2016).

Rolke, R. et al. Quantitative sensory testing: a comprehensive protocol for clinical trials. Eur. J. Pain (Lond. Engl.) 10, 77–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpain.2005.02.003 (2006).

Kortenjann, A.-C. Einfluss einer Ausdauerbelastung auf thermische und mechanische Reizschwellen in der quantitativen sensorischen Testung [Thermal and mechanical thresholds following endurance exercise as assessed by the quantitative sensory testing]. M.A. thesis, Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität (2018).

Urbaniak, G. C. & Plous, S. Research Randomizer (Version 4.0) [Computer software], https://www.randomizer.org/ (2013).

Grone, E. et al. Test order of quantitative sensory testing facilitates mechanical hyperalgesia in healthy volunteers. J. Pain 13, 73–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2011.10.005 (2012).

Kruger, S., Khayat, D., Hoffmeister, M. & Hilberg, T. Pain thresholds following maximal endurance exercise. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 116, 535–540. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-015-3307-5 (2016).

Valenza, A., Bianco, A. & Filingeri, D. Thermosensory mapping of skin wetness sensitivity across the body of young males and females at rest and following maximal incremental running. J. Physiol. 597, 3315–3332. https://doi.org/10.1113/JP277928 (2019).

George, S. Z., Bishop, M. D., Bialosky, J. E., Zeppieri, G. Jr. & Robinson, M. E. Immediate effects of spinal manipulation on thermal pain sensitivity: an experimental study. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 7, 68. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2474-7-68 (2006).

Löfgren, M. et al. Long-term, health-enhancing physical activity is associated with reduction of pain but not pain sensitivity or improved exercise-induced hypoalgesia in persons with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 20, 262. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13075-018-1758-x (2018).

Kosek, E., Ekholm, J. & Nordemar, R. A comparison of pressure pain thresholds in different tissues and body regions. Long-term reliability of pressure algometry in healthy volunteers. Scand. J. Rehabil. Med. 25, 117–124 (1993).

Crombie, K. M., Brellenthin, A. G., Hillard, C. J. & Koltyn, K. F. Endocannabinoid and opioid system interactions in exercise-induced hypoalgesia. Pain Med. 19, 118–123. https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnx058 (2018).

Pud, D., Granovsky, Y. & Yarnitsky, D. The methodology of experimentally induced diffuse noxious inhibitory control (DNIC)-like effect in humans. Pain 144, 16–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2009.02.015 (2009).

Umeda, M. & Okifuji, A. Comparable conditioned pain modulation and augmented blood pressure responses to cold pressor test among resistance exercisers compared to healthy controls. Biol. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2020.107889 (2020).

Eberhard, L. et al. Quantitative sensory response of the SCM muscle on sustained low level activation simulating co-contractions during bruxing. Arch. Oral Biol. 86, 87–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archoralbio.2017.09.030 (2018).

Vaegter, H. B. et al. Exercise increases pressure pain tolerance but not pressure and heat pain thresholds in healthy young men. Eur. J. Pain 21, 73–81. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.901 (2017).

Stackhouse, S. K., Taylor, C. M., Eckenrode, B. J., Stuck, E. & Davey, H. Effects of noxious electrical stimulation and eccentric exercise on pain sensitivity in asymptomatic individuals. PM & R J. Injury Funct. Rehabil. 8, 415–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmrj.2015.07.009 (2016).

Paungmali, A., Joseph, L. H., Sitilertpisan, P., Pirunsan, U. & Uthaikhup, S. Lumbopelvic core stabilization exercise and pain modulation among individuals with chronic nonspecific low back pain. Pain Pract. 17, 1008–1014. https://doi.org/10.1111/papr.12552 (2017).

Assa, T., Geva, N., Zarkh, Y. & Defrin, R. The type of sport matters: pain perception of endurance athletes versus strength athletes. Eur. J. Pain 23, 686–696. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.1335 (2019).

Arroyo-Morales, M. et al. Psychophysiological effects of preperformance massage before isokinetic exercise. J. Strength Cond. Res. 25, 481–488. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181e83a47 (2011).

Fleckenstein, J., Simon, P., Konig, M., Vogt, L. & Banzer, W. The pain threshold of high-threshold mechanosensitive receptors subsequent to maximal eccentric exercise is a potential marker in the prediction of DOMS associated impairment. PLoS ONE 12, e0185463. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0185463 (2017).

Jones, M. D., Nuzzo, J. L., Taylor, J. L. & Barry, B. K. Aerobic exercise reduces pressure more than heat pain sensitivity in healthy adults. Pain Med. 20, 1534–1546. https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pny289 (2019).

Panton, L. B. et al. Relative heart rate, heart rate reserve, and VO2 during submaximal exercise in the elderly. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 51, M165-171. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/51a.4.m165 (1996).

Meeus, M., Roussel, N. A., Truijen, S. & Nijs, J. Reduced pressure pain thresholds in response to exercise in chronic fatigue syndrome but not in chronic low back pain: an experimental study. J. Rehabil. Med. 42, 884–890. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-0595 (2010).

Koltyn, K. F., Garvin, A. W., Gardiner, R. L. & Nelson, T. F. Perception of pain following aerobic exercise. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 28, 1418–1421. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005768-199611000-00011 (1996).

Stevens, C. J., Taylor, L. & Dascombe, B. J. Cooling during exercise: an overlooked strategy for enhancing endurance performance in the heat. Sports Med. 47, 829–841. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-016-0625-7 (2017).

Acknowledgments

Parts of this manuscript constitute the master thesis of Ann-Christin Kortenjann17, this including the study design and parts of the results section, each referenced respectively. Frankfurt am Main, Germany, Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität; 2018). We thank Dr. Christian Koelbl, M.D., Ph.D., Assistant Professor at Columbia University Division at Mount Sinai Medical Center, Miami Beach, USA, to revise our manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.F, A.K and W.B conceived and designed the study. A.K conducted the experiments. J.F and A.K analysed the data. J.F wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kortenjann, AC., Banzer, W. & Fleckenstein, J. Sub-maximal endurance exercise does not mediate alterations of somatosensory thresholds. Sci Rep 10, 10782 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-67700-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-67700-4

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.