Abstract

Bioluminescence, or the production of light by living organisms via chemical reaction, is widespread across Metazoa. Laboratory culture of bioluminescent organisms from diverse taxonomic groups is important for determining the biosynthetic pathways of bioluminescent substrates, which may lead to new tools for biotechnology and biomedicine. Some bioluminescent groups may be cultured, including some cnidarians, ctenophores, and brittle stars, but those use luminescent substrates (luciferins) obtained from their diets, and therefore are not informative for determination of the biosynthetic pathways of the luciferins. Other groups, including terrestrial fireflies, do synthesize their own luciferin, but culturing them is difficult and the biosynthetic pathway for firefly luciferin remains unclear. An additional independent origin of endogenous bioluminescence is found within ostracods from the family Cypridinidae, which use their luminescence for defense and, in Caribbean species, for courtship displays. Here, we report the first complete life cycle of a luminous ostracod (Vargula tsujii Kornicker & Baker, 1977, the California Sea Firefly) in the laboratory. We also describe the late-stage embryogenesis of Vargula tsujii and discuss the size classes of instar development. We find embryogenesis in V. tsujii ranges from 25–38 days, and this species appears to have five instar stages, consistent with ontogeny in other cypridinid lineages. We estimate a complete life cycle at 3–4 months. We also present the first complete mitochondrial genome for Vargula tsujii. Bringing a luminous ostracod into laboratory culture sets the stage for many potential avenues of study, including learning the biosynthetic pathway of cypridinid luciferin and genomic manipulation of an autogenic bioluminescent system.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The production of bioluminescence in animals is an important biological phenomenon that is particularly prevalent in marine environments1. To produce light, animals combine an enzyme (usually a luciferase or photoprotein) and a substrate (luciferin) with oxygen, and sometimes additional components such as ATP or calcium2,3,4. Although the enzymes that produce light are well-studied5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13, and we know how the substrate is produced in bacteria14 fungi15, and partially within Arachnocampa16, we do not yet know the complete biosynthetic pathway for luciferin in any animal system. A comprehensive understanding of this pathway could be transformative for optogenetics in transgenic organisms, where the ability to produce bioluminescence in situ as a biosensor or light source would be invaluable. Some laboratory-reared luminescent animals already exist (Table 1), but may not be suitable for studying luciferin biosynthesis. In particular, ctenophores, cnidarians, and brittle stars use coelenterazine obtained from their diet as a substrate1. Fireflies do use an endogenous luciferin specific to Coleoptera (beetles)17, but they often have longer life cycles than other taxa, slowing research progress18. Although there are other independent origins of autogenic bioluminescence, which we define as light produced via luciferase and luciferin that are synthesized via the genome of the light producing animal, no laboratory cultures of these animals currently exist. This makes additional comparative studies on the evolution of this ability extremely challenging.

Ostracods from the family Cypridinidae independently evolved bioluminescence, and use a luciferin that is endogenous to ostracods and chemically different from that of other bioluminescent organisms2,19,20,21. Of the metazoan taxa already cultured, autogenic luminescence is only known to occur within fireflies22,23, and likely Arachnocampa16,24. Due to the independent origin of ostracod bioluminescence in the family Cypridinidae, and evidence for the autogenic nature of the necessary luciferin and luciferase, ostracods represent an important lineage for understanding how bioluminescence evolved21. Establishing laboratory cultures of luminescent ostracods within Cypridinidae will provide opportunities for new investigations into the biosynthetic pathway of luciferins in Metazoa, as well as comparative studies of the biochemistry, physiology, genetics, and function of endogenous bioluminescence.

Cypridinidae is estimated to include over 300 ostracod species21,25, roughly half of which use bioluminescence, some for defense, while others possess the ability to create bioluminescent courtship displays in addition to luminous defensive secretions21,26,27. Lineages with sexually dimorphic bioluminescent displays, such as those in Cypridinidae, have more species than their non-displaying sister lineages, indicating that origins of bioluminescent courtship may increase diversification rates28. As such, cypridinid ostracods represent an excellent system for understanding how behavioral diversification can lead to increases in species accumulation. Furthermore, cypridinid ostracods diversified while generating bioluminescence with a consistent biochemical basis across the clade29,30, meaning that they use the same luciferin and homologous enzymes to make light. The conserved nature of the luminescent chemical reaction provides a system within which bioluminescence can produce rapid changes in phenotypic diversity by modifying amino acid sequences of the enzyme and how the enzyme is used29.

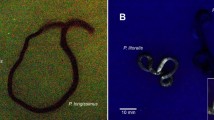

Attempts to culture luminescent and non-luminescent species of Cypridinidae have led to varying success, including Skogsbergia lerneri (non-luminous species with no mating in culture)31, Photeros annecohenae (luminous species without the complete life cycle in culture)32, and Vargula hilgendorfii (luminous species with no mating in culture)33. Researchers attempting to culture Vargula hilgendorfii tried multiple alternative aquarium set-ups and tested sensitivity to nutrients commonly measured in aquaria, but were still unable to induce mating in the lab33. An unnamed species of luminescent ostracod is claimed to have been cultured at the CTAQUA Foundation (Aquaculture and Technological Centre) in Spain for molecular gastronomy34, but no information on species, culture longevity, or whether mating occurred is available on this enigmatic and uncertain culture. Other non-cypridinid ostracods have been reared in the laboratory as well, including the myodocopids Euphilomedes carcharodonta35 and Euphilomedes nipponica36 and the podocopids Xestoleberis hanaii and Neonesidea oligodentata37 (including the only records of copulation in the laboratory for any ostracods)38. Although none are bioluminescent, many podocopids - especially non-marine species - grow quite easily in aquaria, so a number of those have been cultured for descriptions of, or experiments related to, post-embryonic development, including Chlamydotheca incisa and Strandesia bicuspis39, Heterocypris salina40,41,42, Eucypris virens41, and Candona rawsoni42.

In this paper, we present evidence that we are the first to rear a luminous ostracod (Vargula tsujii Kornicker & Baker, 1977) through its complete life cycle in the laboratory. Vargula tsujii is the only bioluminescent cypridinid ostracod described from the Pacific coast of North America. Commonly found in southern California, the reported range of V. tsujii is from Baja California to Monterey Bay43. This species is demersal (moves between the benthic and planktonic environments) and is primarily active in or near the kelp forest at night44. Similarly to some other cypridinid ostracods, Vargula tsujii is a scavenger, and is presumed to feed on dead and decaying fish and invertebrates on the benthos since they can be collected via baited traps. In addition, some authors observed V. tsujii attacking the soft tissues of live fishes caged nearshore45. Vargula tsujii is an important prey item of the plainfin midshipman fish (Porichthys notatus), as it is the source of luciferin for the bioluminescence seen in the fish46.

In addition to evidence for the completion of the life cycle of Vargula tsujii in the laboratory, we provide a successful methodology for culturing populations of V. tsujii, descriptions and analyses of late stage embryogenesis and instar development, a reconstruction of its mitochondrial genome, and a brief description of the distribution of molecular diversity of V. tsujii across coastal southern California.

Methods

Specimen collection

We collected Vargula tsujii from three primary locations at 1–10 m depth: (1) Fisherman’s Cove near Two Harbors on Catalina Island, CA, USA (33°26′42.5″N 118°29′04.2″W) directly adjacent to the Wrigley Marine Science Center, (2) Cabrillo Marina, Los Angeles, CA, USA (33°43′13.5″N 118°16′47.4″W), and (3) Shelter Island public boat ramp, San Diego, CA, USA (32°42′56.3“N 117°13′22.9″W) (Fig. 1; Table S1). We also provide locations in Fig. 1 and Table S1 where we set traps but did not collect V. tsujii. We collected the specimens used for culture and description of the life cycle of V. tsujii exclusively from Fisherman’s Cove, Catalina Island, and we collected additional specimens from the Cabrillo Marina and Shelter Island public boat ramp to discern the genetic diversity of V. tsujii and test for the presence of any cryptic species. For specimen collection we used Morin pipe traps: cylindrical polyvinyl chloride (PVC) tubes with mesh funnels to prevent the ostracods from escaping once they entered47. We baited traps with dead fish or fresh chicken liver (roughly 1–2 cm3). We set traps in 1–10 meters of water at sunset and collected them 1.5 to 2 hours after last light to allow time for the ostracods to accumulate.

Map of localities where collections (and attempted collections) of Vargula tsujii were made. Black points represent geographic annotations for reference, purple points refer to the location where ostracods were collected that were ultimately cultured, blue where animals were found or collected, orange where Kornicker originally collected animals, and red where no V. tsujii were found. (A) Map of the California (USA) coastline where collections were attempted; (B) Map of the region near Two Harbors (Santa Catalina Island, California, USA) where collections were attempted. Figure generated using the R (version 3.6.2) package ggmap. Map tiles by Stamen Design, under CC BY 3.0. Data by OpenStreetMap, under ODbL.

Population genetic analyses

We obtained Vargula tsujii sequence data for 16S rRNA (16S) and cytochrome oxidase 1 (COI) from a previously published thesis48. We then aligned and visually inspected sequence chromatograms with Sequencher version 3.1 (Gene Codes Corp) (Table S1). We constructed haplotype networks for the two genes, COI (Number of individuals: Catalina, 18; San Diego, 11; San Pedro, 12) and 16S (Number of individuals: Catalina, 19; San Diego, 20; San Pedro, 21) with the package pegas49 in the R environment (version 3.4.2)50. To assess whether sequences within populations cluster together, we analyzed each gene via Discriminant Analysis of Principal Components (DAPC) using the adegenet package in R51 and compared models with one, two, and three clusters using the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC)52.

Description of aquarium system and feeding

We cultured Vargula tsujii at the University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB) in aquaria designed for water to flow through sand and out the bottom. This allowed continuous water flow to keep water fresh, and not suck ostracods into a filter. Instead, ostracods remain in sand where they spend the daylight hours. We obtained the seawater for this system through intake structures at UCSB located 2,500 feet offshore of campus beach at a depth of 51 feet under local conditions (12–18 °C sea surface temperature). The water in our tanks tends to fall between 16–18 °C because it warms in the building before being distributed to tanks. We kept animals under a 12:12 light cycle with an indirect blue LED light.

We first modified a five gallon glass tank by drilling a hole in the bottom, which was then covered with the bottom of an undergravel filter and a 3 cm layer of commercial aragonite sand with grain sizes 1–2 mm for aquariums (CaribSea brand). To maintain continuous water flow, we used plastic tubing (diameter = 1 cm) connected directly to an overflowing reservoir tank, itself fed by UCSB’s seawater system that pumps directly from the Pacific Ocean. The tube from the reservoir created a siphon system for moving water into the main tank (Fig. 2). The siphon provided continuous water flow when needed, and prevented overflow of the aquarium. In addition, to prevent a complete drain of the water if the siphon flow broke, which is common with larger siphons, we attached an outflow pipe to the bottom of the aquarium that drained halfway up the side of the tank (Fig. 2).

Diagrammatic representation of aquarium setup for Vargula tsujii. (A) Source water flows into (B) a reservoir tank, which overflows to keep the reservoir full and water level constant. (C) We use a siphon to carry water from a reservoir tank to main aquarium where ostracods live. Water level of the main tank drains through sand (stippled), through (E) an outflow that is raised to a level that would cause water to remain at the level of the dashed line, even if a siphon is interrupted to cause water to stop flowing into the main tank. (F) Plastic bottle and parts used to create small aquarium using the same logic as main aquarium. (G) Custom-built acrylic aquarium with drain in bottom and raised outflow with adjustable rate.

We also created a similar system for smaller experimental aquaria, but these appeared to be less effective long-term, as we saw high mortality in non-systematic studies. For the small aquaria (“condos”), we cut a large hole (~5 cm diameter) into the bottom of 500 mL Nalgene Square PETG Media Bottles with Septum Closures (Figs. 2F, S7). We then modified a 100 μm cell strainer to fit in the bore of the media bottle in such a way that it would remain there when the closure of the media bottle was screwed back on, allowing water but not sand to flow through. We inverted the bottle and added a ~3 cm layer of sand above the cell strainer, measured from the edge of the bottle cap. In plain terms, the condos are simply capped bottles, turned upside down, after creating a large hole in the bottom and a small hole in the cap. We placed a strainer in the cap so water can flow down through the cap and not get clogged by sand. For these smaller aquaria, we used 5 mm diameter tubing as siphons from the reservoir tank and for the outflow. Similar to the large tank, the outflow tubes (placed in the septum closure) drained roughly halfway up the side of the aquaria to prevent the water from draining completely.

Most recently, we created custom aquariums from acrylic (Fig. 2G), with similar dimensions to the 5-gallon glass aquarium. We installed a bulkhead in the bottom and attached PVC tubing as a drain, which we again raised to about half the height of the aquarium to prevent complete drainage if inflow of water stops accidentally. We added a valve to control the rate of outflow and instead of a siphon, we added a float switch to set inflow rate. In the latest iteration of the aquaria, we raise the outflow pipe to set the level of water in the aquarium and use continuous inflow directly to the main aquarium, which works well as long as the water is draining freely. We use a flow rate of approximately 0.4 L/min.

We initially offered the ostracods multiple diet choices, including: (1) imitation crab, which is primarily pollock, (2) carnivore fish pellets or TetraMin fish flakes (Tetra, Blacksburg, VA), (3) tilapia fillets, and (4) anchovies, which have each made for successful food sources in Caribbean ostracods (Todd Oakley, personal observation32,47). Although the adults appeared moderately interested in these food sources in non-systematic trials, we found the juvenile ostracods did not eat them, but they did actively feed on raw chicken liver, as do Vargula hilgendorfii individuals from Japan53. In culture, we therefore provided pieces of chicken liver daily (~1 cm3 per 200 animals). Due to the nocturnal life history of V. tsujii, we fed them in the late afternoon or early evening (around the beginning of the dark cycle), and removed the food from the aquarium in the morning (~3–5 hours into the light cycle).

Rearing of embryos

We tested two primary methods for rearing embryos. The first was less successful in terms of longevity of both the mothers and embryos, but provided usable data on embryogenesis. Regardless of method, adult female ostracods did not appear to eat while they were brooding.

For the first method, we kept females individually in circular wells in twelve-well dishes32, with approximately 1 mL of 17 °C seawater. We recorded visual observations of the females and their embryos and changed the water daily. The advantage of this method is ease of identification and observation of individual ostracods, allowing us to track the growth of specific embryos over a given period of time. However, all females which deposited embryos into the brooding chamber died before their embryos were released from the marsupium, although the precise cause of death is unknown. These embryos were then removed from the female marsupium by dissection, kept in wells, and observed until the animals hatched through the chorion (see Supplemental Video).

For the second method, we identified and removed brooding females from the aquarium and placed them in 50 mL Falcon tubes (2 females per tube). Roughly 5 mL of commercial aragonite sand for saltwater aquariums with most grain sizes 1.0–2.0 mm (Caribsea brand) was added to the bottom of each tube to allow females to burrow. Falcon tubes were then placed in a large seawater reservoir that ranged from 17–19 °C. We changed the water in each tube daily, and imaged brooding females every other day with a camera attached to a dissecting scope. We used key diagnostic features such as number of embryos and female size to distinguish individual females from one another. Of the thirteen individuals kept in Falcon tubes, only one died prior to embryo release from the marsupium.

Animal measurements and inferences of instar size classes

We imaged all ostracods using a standard dissecting microscope and an Olympus brand camera. We then measured carapace length, carapace height, eye width, and keel width with the software Fiji (Sample size = 626 individuals; Table S3)54. These parameters are useful in the determination of the instar stages in other bioluminescent ostracods32. A subset of these individuals (9 males, 11 females) were dissected to confirm sex. We partitioned the data into clusters using the KMeans clustering algorithm implemented in scikit-learn55 in Python 2.756. KMeans fits the data into k clusters, specified in the arguments, sorting each data point into the cluster which has the minimum euclidean distance to the centroid of the cluster. We originally specified the value for k as eight based on the five known stages of instar development for related species of ostracods plus the embryonic stage and adult males and females. However, a k-value of eight clusters resulted in a split of the inferred adult female cluster into two clusters rather than the discrimination of adult males from inferred A-I instars. To avoid this apparent over-clustering, we ran our final analysis with a k-value of seven, which retained all inferred adult females in a single cluster but was unable to distinguish an adult male cluster from the inferred A-I instars. We assigned development stages to each cluster based on the relationship by comparison to the closely related Photeros annecohenae, which grew in 12-well dishes to allow more precise documentation of instars32. We further split the A-I instar/Adult male cluster using the KMeans algorithm and a k-value of 3 with more precise measurements of length, height, and eye width, as well as eye to keel distance (EKD) from an additional sample of individuals that fell within this cluster (Sample size = 43). We measured eye to keel distance by calculating the length between the farthest point of the eye from the front of the ostracod to midway on the keel of the animal. We then assigned three new clusters to development stages by comparing eye size and shape parameters with what we expect based on Photeros annecohenae32.

Whole genome sequencing

We froze four adult female Vargula tsujii, collected from the WMSC Dock on 2017–09–01 in liquid nitrogen and shipped the specimens on dry-ice to the Hudson Alpha Institute for Biotechnology Genomic Services Lab (HAIB-GSL; Huntsville, AL) for genomic DNA extraction and Chromium v2 Illumina sequencing library preparation. HAIB-GSL extracted the DNA using the Qiagen MagAttract Kit, yielding 141 ng, 99 ng, 153 ng, and 96 ng of extracted DNA respectively. This quantity of DNA was not sufficient for a size distribution analysis via agarose pulse field gel analysis, therefore we decided to proceed with Chromium v2 library prep with the 153 ng sample (sample # 5047/TCO4), without confirmation of a suitable high-molecular weight DNA size distribution. We sequenced this library on three lanes of a HiSeqX instrument using a 151 × 151 paired-end sequencing mode, resulting in a total of 910,926,987 paired reads (260.6 Gbp). We attempted whole genome assembly of the resulting sequencing data with the Supernova v2.0.0 genome assembly software57, using default parameters. Pseudo-haplotype (pseudohap) paths through the assembly graph were then extracted using the Supernova ‘mkoutput’ command. The ‘raw’ assembly graph with full headers was also output to FASTA format using supernova ‘mkoutput’, and was then converted to the GFA assembly graph format using the supernova2gfa utility of gfaview (https://github.com/lh3/gfa1). After sequencing and library construction, remaining DNA was shipped on dry-ice from HAIB-GSL to MIT. We then used the high-sensitivity Agilent Femto Pulse High Molecular Weight DNA capillary electrophoresis instrument at the MIT BioMicro Center (Cambridge, MA) to perform an analysis of the size distribution of the remaining extracted DNA, including the sample used for Chromium library preparation.

Mitochondrial genome assembly

To achieve a full length mitochondrial genome (mtDNA) assembly of V. tsujii, we partitioned and assembled sequences separately from the nuclear genome. We first mapped Illumina reads from our Chromium libraries (Table S4) to the known mtDNA of the closest available relative, Vargula hilgendorfii (NC_005306.1)58 using bowtie2 (v2.3.3.1)59 (parameters:–very-sensitive-local). We then extracted read pairs with at least one read mapped from the resulting BAM file with samtools (parameters: view -G 12), name-sorted, extracted in FASTQ format (parameters: samtools fastq), and input the reads into SPAdes (v3.11.1)60 for assembly (parameters:–only-assembler -k55,127). We inspected the resulting assembly graph using Bandage (v.0.8.1)61 and performed a heuristic manual deletion of low coverage nodes (deletion of nodes with coverage <200x, mean coverage ~250x), which resulted in two loops with sequence similarity to the V. hilgendorfii mtDNA that both circularized through a single path (Supplementary Figure S1). We then manually inspected this graph via a blastn (2.7.1+)62 aligned against the V. hilgendorfii mtDNA through SequenceServer (v1.0.11)63 and visualized with the Integrated Genomics Viewer (v2.4.5)64. We noted that the single circularizing path was homologous to the two duplicated control regions reported in the V. hilgendorfii mtDNA58. We surmised that this assembly graph structure indicated the V. tsujii mtDNA had the same global structure as the V. hilgendorfii mtDNA, and so used the Bandage “specify exact path” tool to traverse the SPAdes assembly graph and generate a FASTA file representing the circularized V. tsujii mtDNA with the putative duplicated control regions (Figure S1). To avoid splitting sequence features across the mtDNA circular sequence break, we circularly rotated this full assembly with the seqkit (v0.7.2)58,65 “restart” command, to set the first nucleotide of the FASTA file at the start codon of ND2. We then confirmed 100% of the nucleotides via bowtie2 re-mapping of reads and polishing with Pilon (v1.21)66 (parameters:–fix all). We annotated the final assembly of the mitochondrial genome using the MITOS2 web server67 with the invertebrate mitochondrial genetic code (Number 5). We manually removed low confidence and duplicate gene predictions from the MITOS2 annotation.

Results

Population genetics analyses

Our COI haplotype network revealed minimal structure among V. tsujii populations in southern California (Fig. 3A). Haplotypes from San Pedro and Catalina Island overlap or diverge by only one to three mutations. Haplotypes from San Diego individuals, although still very similar to haplotypes from Catalina Island and San Pedro, differ by at least eight mutations and show no overlap with haplotypes from other populations of V. tsujii. However, the haplotype network for 16S indicates that sequences from San Diego individuals are identical to some individuals from the other two populations (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, although the model with three clusters was favored in the DAPC analysis for each gene (Supplementary Figures S2 and S3), membership in five of the six clusters includes individuals from different populations (Supplementary Figures S4 and S5). Therefore our analyses do not support three genetically distinct populations as defined by location.

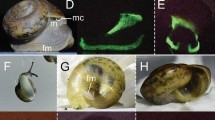

Embryogenesis description

After fertilization and release into the marsupium, V. tsujii embryos resemble opaque, green, ovoidal embryos (Figs. 4 and 5). After five to eight days of growth, separation of the yolk begins, which appears as a light green mass condensed within the embryo. Around ten to eighteen days after deposition into the brooding chamber, two very small red lateral eyespots are visible on each embryo and the separation of the yolk continues. Daily observations over the next six days showed continual growth and darkening of the eyes. By day sixteen the yolk is almost completely separated and has begun to form the gut of the ostracod. By days fifteen to nineteen, the eyespots are mostly black and the light organ (a light brown/yellow mass) appears anteroventral to the eyes of the embryo. Around twenty days after deposition, developing limbs in the form of two rows of small brown masses are visible along the ventral side of the embryos. At this point the gut has finished forming within the carapace and is visible as a yellow-white mass on the posterior end of each embryo. Limb formation continues over the next few days, and the eyes of each embryo become entirely black. Twenty-five to thirty-eight days following embryo deposition, embryogenesis is complete, and first (=A-V, or adult minus 5) instars are released from the mother’s marsupium.

Summary of the timing of stages of embryogenesis in Vargula tsujii. This represents the complete range of first-appearance of each feature across multiple broods, including: yolk separation (range = 5–8 days, N = 7); eye-spot formation (range = 10–18 days, N = 12); upper lip formation (range = 15–19 days, N = 3); limb formation (range = 18–23 days, N = 11); hatching (range = 25–38 days, N = 11).

Instar development

We inferred five juvenile instar stages (A-I, A-II, A-III, A-IV, A-V) and an adult stage for Vargula tsujii (Figs. 6, 7A; Table 2). Laboratory measurements of specimens of unknown sex were compared with the measurements of sexed individuals (9 males, 11 females) to confirm interpretation of the instar stage of size classes (Fig. 7C,D). Due to large amounts of overlap of A-I females with adult and A-I males, these three groups are currently indistinguishable in the large data set. However, when we attempted to distinguish these stages using additional measurements (particularly eye-to-keel distance, EKD), we find that EKD differentiates A-I males and females, and that length separates the A-I instars from adult males (Figs. 6E–G, 8; Table 3). Sexual dimorphism in size becomes apparent in adulthood, with adult females (Length ± SD = 1.983 ± 0.0798) clearly larger than adult males (Length ± SD = 1.647 ± 0.028). However, compared to many other cypridinid ostracods, this dimorphism can be difficult to assess visually without a side-by-side comparison.

Images of selected individuals within each inferred instar stage: (A) Newly hatched A-V instar beside its shed chorion and an embryo still within the chorion, (B) A-V, (C) A-IV, (D) A-III, (E) A-II, (F) A-I male, (G) A-I female, (H) Adult male, (IU) Adult female. Scale bar only for B-I, no scale for A. Abbreviations: A-V, instar 1, ch, chorion, em, embryo still within chorion.

(A) KMeans clusters of Vargula tsujii developmental stages based on carapace height and width. Instar stages were assigned to each cluster via comparison to P. annecohenae and additional analysis of male and female size-dimorphism. (B) Points representing laboratory cultured animals overlayed on wild caught and unknown data. Different colors represent different clusters in the KMeans analysis, and are labeled with their inferred instar/adult stages. (C) Shows wild-caught animals dissected and identified as female in relation to the KMeans clusters, and (D) shows wild-caught animals dissected and identified as male in relation to the KMeans clusters.

Plot of length versus eye-to-keel distance (EKD) in animals assigned to the A-I Instar/Adult Male cluster in the previous KMeans analysis (Fig. 7A). These points were then clustered via KMeans analysis into three clusters, which we assigned to A-I Males (red), A-I Females (blue), and Adult Males (yellow).

Evidence for complete life cycle in the lab

To assess whether a complete life cycle was obtained in the laboratory, we began with only brooding females in a small experimental aquarium (“condo”). Those brooding females, although not tracked individually, released a number of juveniles, which we measured intermittently over time (Fig. 7B). In this aquarium we found juveniles, and eventually adults, that fell across the full size range of wild-caught ostracods. After all of the broods initially hatched, we removed all adult females from the experimental aquarium to assess whether the ostracods would mature and mate in the laboratory. To ensure that all adult females were removed, we disassembled the small experimental aquarium and examined each animal under a dissecting microscope. We then reassembled and added only the subadult animals back into the aquarium. Following removal of the original adult females, we found adult brooding females that grew up in experimental aquarium that themselves gave birth to the next generation in 3–4 months time.

Nuclear and mitochondrial genome assemblies

The primary and alternate pseudohaplotypes of the draft Supernova nuclear genome assembly (available in the Dryad repository, doi:10.6075/J0DZ06QQ) are composed of 492,119 and 492,119 scaffolds containing 897,640,719 and 897,646,086 bp respectively. The raw assembly graph consists of 8,259,570 edges representing 3,240,040,938 bp. The Agilent Femto Pulse capillary electrophoresis DNA sizing results (measured after library construction & sequencing) indicate that the mode of the DNA size distribution of the four extracts were 1244 bp, 3820 bp, 1285 bp (sample #5047, used for sequencing), and 1279 bp. Overall, our final Vargula tsujii nuclear genome assembly is highly fragmented, with an indication of high levels of heterozygosity between haplotypes (~5%) and a high proportion of simple sequence repeats.

The final V. tsujii mtDNA (15,729 bp) (Fig. 9) aligned to the previously published V. hilgendorfii mtDNA with 98% coverage and 78.5% nucleotide identity, and is available on NCBI GenBank (MG767172). The V. tsujii mtDNA contains 22 tRNA genes, 13 protein coding genes, and 2 duplicated control regions in an identical positioning and orientation to the V. hilgendorfii mtDNA. The V. tsujii duplicate control regions (661 bp, 570 bp), are smaller than the homologous V. hilgendorfii control regions (855 bp, 778 bp). The alignment of the V. tsujii control regions to the V. hilgendorfii control regions indicate they possess reasonable nucleotide identity (~73%), but the presence of unalignable regions ~20% of the length of the regions suggests evolution constrained by size and/or GC% content rather than sequence identity alone. There is one polymorphic base in the final mitogenome assembly coding for a synonymous wobble mutation in the COII gene (COII:L76).

Mitochondrial genome of Vargula tsujii. Note the duplicated control regions, CR1 and CR2 (in gray). Figure produced with Circos (version 0.69; http://circos.ca/)89.

Discussion

Based on measurement data on the first and second generations of ostracods reared in the lab (Fig. 7), and the presence of brooding female ostracods in our experimental aquarium where adult females had previously been removed, we can infer that we were successful in rearing Vargula tsujii through its complete life cycle in the lab. This is a first for any bioluminescent ostracod, as rearing in the lab has remained a significant hurdle for laboratory studies in these animals32,33. However, despite recent improvements, challenges still remain. Recent improvements (as described in the methods) include adding a neoprene gasket to the edge of the false bottom (Supplementary Figure S7) to prevent sand and detritus from falling below and fouling the aquarium and periodically siphoning the surface of the sand in the aquarium to reduce build-up of detritus and fouling microorganisms. But previous challenges mean our current population of animals is relatively small (between 500 and 1000 individuals), and we do not yet know if it is possible to continue the culture indefinitely without new input of animals. Previously, we added new wild-caught animals about every 6 months to increase the population size, but at the time of re-submission we have a culture that has been thriving for 10 months without the addition of new individuals. The primary challenge currently is populations within small-volume aquariums (condos) are very prone to collapse, and animals do not survive long in 12-well dishes as they did in P. annecohenae32, limiting current experimental work because tracking individuals is not possible.

Our current population was cultured from animals collected near Wrigley Marine Science Center on Santa Catalina Island, which appears to contain much of the genetic diversity sampled across much of the known range of V. tsujii (Fig. 3). Our population genetic analyses support the hypothesis that populations of Vargula tsujii experience some gene flow across the localities sampled, including Catalina Island. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that V. tsujii represents a single, connected species. As such, we assume our culture of ostracods from Santa Catalina Island, and inferences made from it, may apply to populations of V. tsujii across southern California coastal systems. However, we cannot discount the possibility that there might be some variation in development times and instar sizes across the range of this species. Also of note is that this species is not easily collected throughout the reported range, and northern populations, if they exist, may be divergent from southern California populations.

Attempted whole genome reconstruction

The 1C genome size of Vargula tsujii was previously reported to be 4.46 ± 0.08 pg (Female, n = 3), and 4.05 pg (Male, n = 1)68, corresponding to a 1C genome size of 4.36 Gbp and 3.96 Gbp respectively and suggesting XO sex determination. Our nuclear genome assembly is congruent with these past reports and indicates a genome size of greater than 3.2 Gbp for an adult female V. tsujii. Our reconstruction of the Vargula tsujii nuclear genome assembly is highly fragmented, however, with an indication of high levels of heterozygosity between haplotypes and a high proportion of simple sequence repeats. We speculate that our poor nuclear genome assembly results are likely due to the very small size distribution of the input DNA, as larger fragment sizes are especially critical for the reconstruction of large genomes such as V. tsujii. Further protocol development is needed to extract suitable High Molecular Weight DNA, which could allow long-read sequencing that would improve assembly, but we note that assembly of very large genomes of high heterozygosity is non-trivial and is an active area of genome assembler research. Our results may also be due to the poor handling of high-heterozygosity species by the 10x Genomics Chromium platform (anecdotally), which notably is now discontinued by 10x Genomics as a library preparation and sequencing product. Alternative approaches to improve our V. tsujii nuclear genome assembly are currently in progress.

The life cycle of Vargula tsujii

The embryogenesis of Vargula tsujii is similar to closely related species, and the 24-day average brooding duration falls within the range for other cypridinid ostracods (10–30 days)69. The primary stages of V. tsujii late-stage embryogenesis are yolk separation, formation of eye spots, development of the upper lip, development of limbs, and emergence from the chorion and marsupium (Fig. 5). In general, the late-stage embryonic development of Vargula tsujii is longer than that of other luminescent ostracods whose development has been described (Table 4). Longer overall development in the temperate V. tsujii is consistent with work in other crustaceans, which indicates that temperature has an inverse relationship with development time70. However, earlier embryonic development in V. tsujii is faster than in the tropical P. annecohenae. In P. anncohenae, yolk separation begins on day 9 and eye development begins on days 14–1532, while those stages begin at 5–7 and 10–13 days, respectively, in V. tsujii. Additionally, the order of development in V. tsujii appears to differ from that of Vargula hilgendorfii, which starts to develop limbs on days 4–5, before eye and upper lip development71. By contrast, V. tsujii limbs do not appear until after eye-spot and upper lip formation. The reasons for this difference are unclear.

Juvenile development of Vargula tsujii is also quite similar overall to that of Photeros annecohenae, the only other bioluminescent cypridinid ostracod for which instar developmental data are available32. We inferred five distinct instar stages (A-V through A-I), and A-I instars develop into size dimorphic adult males and females (Tables 2 and 3). It is important to note that these inferences represent hypotheses that can be tested by rearing and measuring individuals through molts, which we have not yet been able to accomplish in our culture. However, average measurements of size, including carapace length and height, as well as eye width, were comparable between respective instar stages in V. tsujii (inferred) and P. annecohenae (observed). However, in V. tsujii average eye width remains within the range of 0.0600 mm to 0.0684 mm from the embryonic stage until the second instar, and makes a large jump by about two fold in the third instar (0.121 ± 0.0208 mm), as compared to a gradual increase in eye size in P. annecohenae. In our KMeans clustering analysis, the second-to-largest cluster of V. tsujii appears to contain adult males as well as A-I males and females. This finding differs from that in P. annecohenae, where adult males were found to cluster separately from A-I males and females and adult females based on size and shape, and A-I males and females could be distinguished by certain shape parameters, as well as eye size32. In V. tsujii, we can largely differentiate adult and A-I males from females by eye-to-keel distance (EKD), which was not measured in previous studies32, and adult males can be separated from A-I males by length (Fig. 8; Table 3). We hypothesize that this apparent reduction of sexual dimorphism observed in the later stages of development, compared to P. annecohenae, may occur because V. tsujii may have lost the ability to use luminescence for courtship26, so selection acting on differences in male and female shape may have been reduced.

Benefits of completing the life cycle

Cypridinid ostracods represent an independent origin of endogenous autogenic bioluminescence. This group is a natural comparison to other, well-studied bioluminescent courtship systems, such as that of fireflies72. Other possible laboratory models for bioluminescence, such as brittle stars73 and cnidarians74 are useful for some research tasks, such as studies of luciferins obtained from the diet (e.g., coelenterazine). Others might be easier to rear in the laboratory, such as the self-fertilizing brittle star Amphiolus squamata75. However, ostracods produce their own luciferase and luciferin, unlike brittle stars and cnidarians. Ostracods also have relatively fast generation times (on the order of months), which can be modified somewhat by adjusting the temperature of the water, as is common among ostracods31,32,33,76,77. In comparison, fireflies are usually on a six-month to one-year life cycle that is difficult to alter78,79,80, and some brittle stars appear to spawn only seasonally81,82. Furthermore, culture of an organism (Vargula tsujii) from a clade with an independent origin of autogenic bioluminescence allows for comparative studies between luminescence in ostracods and the autogenic bioluminescence found in fireflies17 or other organisms, which would not otherwise be possible.

Ostracods will be incredibly useful for studying the physiology and biochemistry of bioluminescence2,21, as both diversification and behavioral changes in cypridinids related to luminescence have occurred using the same luciferin and homologous luciferases30. Furthermore, although Vargula tsujii itself does not possess bioluminescent signaling for courtship, we expect a similar culturing system could be useful for some signaling species as well, at least those that come to baited traps. Given that ostracod courtship signals may be simulated in a laboratory setting, this system could allow us to assess male and female behavior in response to changes in signal parameters, such as intensity, color, and pulse duration83. These tools will provide researchers with an excellent system for asking important questions related to selection on genes important for rapid diversification84, including those related to behavior85, sexual selection86, and the role of the biochemical properties of bioluminescence29.

Importantly, the biosynthetic pathway for luciferin production is currently unknown for any animal. One major obstacle to describing this pathway has been building laboratory cultures for animal species that produce luciferin themselves and also have a relatively fast generation time. Solving this bottleneck to accessing specimens for bioluminescent ostracods has set the stage for investigations into the biosynthetic pathway of cypridinid luciferin and its possible use in biomedical tools such as optogenetics87. Finally, this is an excellent system with which to consider developing genome editing techniques (e.g., CRISPR/Cas9)88 to test candidate genes for luciferin biosynthesis and to assess how genetic variants in critical genes might affect production or perception of bioluminescent signals.

Data availability

Sequence data for COI and 16S are available in GenBank (Table S2) and our whole genome Chromium reads are available in the Sequence Read Archive (SRR9308458). The final V. tsujii mtDNA is available on GenBank (MG767172). Femto pulse results, the pseudohaplotype files, and converted assembly graph for our Supernova nuclear genome assembly are available in the Dryad repository (doi:10.6075/J0DZ06QQ). Scripts and data for the population genetics and k-means clustering analyses are provided on Github (https://github.com/goodgodric28/vargula_tsujii_culture). An additional video which shows Vargula tsujii hatching from the chorion and outside the mother is provided on Youtube (https://youtu.be/8o5CqHTcTjI). Those interested in starting their own V. tsujii culture from our current laboratory culture should contact the corresponding author for details.

References

Haddock, S. H. D., Moline, M. A. & Case, J. F. Bioluminescence in the sea. Ann. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2, 443–493 (2010).

Hastings, J. W. Biological diversity, chemical mechanisms, and the evolutionary origins of bioluminescent systems. J. Mol. Evol. 19, 309–321 (1983).

Shimomura, O., Johnson, F. H. & Saiga, Y. Extraction, purification and properties of aequorin, a bioluminescent protein from the luminous hydromedusan, Aequorea. J. Cell. Comp. Physiol. 59, 223–239 (1962).

Tsuji, F. I. ATP-dependent bioluminescence in the firefly squid, Watasenia scintillans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 82, 4629–4632 (1985).

Cormier, M. J., Wampler, J. E., Hori, K. & Lee, J. W. Bioluminescence of Renilla reniformis. IX. Structured bioluminescence. Two emitters during both the in vitro and the in vivo bioluminescence of the sea pansy, Renilla. Biochemistry 10, 2903–2909 (1971).

Dunlap, P. Biochemistry and Genetics of Bacterial Bioluminescence. In Advances in Biochemical Engineering/Biotechnology 37–64 (2014).

Fallon, T. R. et al. Firefly genomes illuminate parallel origins of bioluminescence in beetles. Elife 7 (2018).

Sweeney, B. The bioluminescence of dinoflagellates. In Biochemistry and Physiology of Protozoa 287–306 (1979).

Kobayashi, K. et al. Purification and properties of the luciferase from the marine ostracod Vargula hilgendorfii. In Bioluminescence and Chemiluminescence, https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812811158_0022 (2001).

Hastings, J. W., Vergin, M. & Desa, R. Scintillons: The Biochemistry of Dinoflagellate Bioluminescence. In Bioluminescence in Progress 301–330 (Princeton University Press, 1967).

Nakatsu, T. et al. Structural basis for the spectral difference in luciferase bioluminescence. Nature 440, 372–376 (2006).

Marques, S. M. & Esteves da Silva, J. C. G. Firefly bioluminescence: a mechanistic approach of luciferase catalyzed reactions. IUBMB Life 61, 6–17 (2009).

Verhaegent, M. & Christopoulos, T. K. Recombinant Gaussia luciferase. Overexpression, purification, and analytical application of a bioluminescent reporter for DNA hybridization. Anal. Chem. 74, 4378–4385 (2002).

Dunlap, P. V. & Urbanczyk, H. Luminous Bacteria. In The Prokaryotes (eds. Rosenberg E., DeLong, E. F., Lory, S., Stackebrandt, E. & Thompson, F.) 495–528 (Springer, 2013).

Kotlobay, A. A. et al. Genetically encodable bioluminescent system from fungi. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 12728–12732 (2018).

Watkins, O. C., Sharpe, M. L., Perry, N. B. & Krause, K. L. New Zealand glowworm (Arachnocampa luminosa) bioluminescence is produced by a firefly-like luciferase but an entirely new luciferin. Sci. Rep. 8, 3278 (2018).

Kanie, S., Nakai, R., Ojika, M. & Oba, Y. 2-S-cysteinylhydroquinone is an intermediate for the firefly luciferin biosynthesis that occurs in the pupal stage of the Japanese firefly, Luciola lateralis. Bioorg. Chem. 80, 223–229 (2018).

McLean, M., Buck, J. & Hanson, F. E. Culture and larval behavior of photurid fireflies. Am. Midl. Nat. 87, 133 (1972).

Thompson, E. M., Nagata, S. & Tsuji, F. I. Cloning and expression of cDNA for the luciferase from the marine ostracod Vargula hilgendorfii. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86, 6567–6571 (1989).

Oba, Y., Kato, S.-I., Ojika, M. & Inouye, S. Biosynthesis of luciferin in the sea firefly, Cypridina hilgendorfii: l-tryptophan is a component in Cypridina luciferin. Tetrahedron Lett. 43, 2389–2392 (2002).

Morin, J. G. Luminaries of the reef: The history of luminescent ostracods and their courtship displays in the Caribbean. J. Crust. Biol. 39, 227–243 (2019).

de Wet, J. R., Wood, K. V., Helinski, D. R. & DeLuca, M. Cloning of firefly luciferase cDNA and the expression of active luciferase in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 82, 7870–7873 (1985).

Seliger, H. H., McElroy, W. D., White, E. H. & Field, G. F. Stereo-specificity and firefly bioluminescence, a comparison of natural and synthetic luciferins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 47, 1129–1134 (1961).

Takaie, H. Ten years of the glow-worm (Arachnocampa richardsae) rearing at Tama Zoo–Fascination of a living milky way. Insectarium 34, 336–342 (1997).

Brandão, S. N., Angel, M. V., Karanovic, I., Perrier, V. & Meidla, T. World Ostracoda Database. http://www.marinespecies.org/ostracoda, https://doi.org/10.14284/364 (2019).

Cohen, A. C. & Morin, J. G. Sexual morphology, reproduction and the evolution of bioluminescence in Ostracoda. Paleontological Society Papers 9, 37 (2003).

Morin, J. G. Firefleas of the Sea: Luminescent Signaling in Marine Ostracode Crustaceans. The Florida Entomologist 69, 105 (1986).

Ellis, E. A. & Oakley, T. H. High rates of species accumulation in animals with bioluminescent courtship displays. Curr. Biol. 26, 1916–1921 (2016).

Hensley, N. M. et al. Phenotypic evolution shaped by current enzyme function in the bioluminescent courtship signals of sea fireflies. Proc. R. Soc. B 286, 20182621 (2019).

Morin, J. G. Based on a review of the data, use of the term ‘cypridinid’ solves the Cypridina/Vargula dilemma for naming the constituents of the luminescent system of ostracods in the family cypridinidae. Luminescence 26 (2011).

Cohen, A. C. Rearing and postembryonic development of the myodocopid ostracode Skogsbergia lerneri from coral reefs of Belize and the Bahamas. J. Crust. Biol. 3, 235–256 (1983).

Gerrish, G. A. & Morin, J. G. Life cycle of a bioluminescent marine ostracode, Vargula annecohenae (Myodocopida: Cypridinidae). J. Crust. Biol. 28, 669–674 (2008).

Wakayama, K. & Kanazawa, K. Elucidation of environmental tolerance of sea fireflies and research on construction of optimal rearing environment. Sci. J. Kangawa U. 25, 117–124 (2014).

Pérez-Lloréns, J. L. Cooking-Science-Communication (CSC): The ideal trident to enjoy the dining experience. Int. J. of Gastron. Food Sci. 16, 100134 (2019).

Koyama, K. H. & Rivera, A. S. Embryonic development of the myodocopid ostracod Euphilomedes carcharodonta Smith, 1952. J. Crust. Biol. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcbiol/ruy088 (2018).

Kawamata, K., Sato, M. & Abe, K. Complete life cycle of the ostracod Euphilomedes nipponica (Myodocopida, Philomedidae). Plankton Benthos Res. 13, 83–89 (2018).

Smith, R. J. & Kamiya, T. The Ontogeny of Neonesidea oligodentata (Bairdioidea, Ostracoda, Crustacea). Hydrobiologia 489, 245–275 (2002).

Ikeya, N. & Kato, M. The life history and culturing of Xestoleberis hanaii (Crustacea, Ostracoda). In Evolutionary Biology and Ecology of Ostracoda (eds. Horne, D. J. & Martens, K.) 149–159 (Springer Netherlands, 2000).

Liberto, R., César, I. I. & Mesquita-Joanes, F. Postembryonic growth in two species of freshwater Ostracoda (Crustacea) shows a size-age sigmoid model fit and temperature effects on development time, but no clear temperature-size rule (TSR) pattern. Limnology 15, 57–67 (2014).

Kubanç, N., Özuluğ, O. & Kubanç, C. The ontogeny of appendages of Heterocypris salina (Brady, 1868) Ostracoda (Crustacea). In Ostracodology — Linking Bio- and Geosciences 255–272 (2007).

Smith, R. J. & Martens, K. The ontogeny of the cypridid ostracod Eucypris virens (Jurine, 1820) (Crustacea, Ostracoda). In Evolutionary Biology and Ecology of Ostracoda (eds Horne, D. J. & Martens, K.) vol. 148 31–63 (Springer, 2000).

Engstrom, D. R. & Nelson, S. R. Paleosalinity from trace metals in fossil ostracodes compared with observational records at Devils Lake, North Dakota, USA. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 83, 295–312 (1991).

Korniker, L. S. & Baker, J. H. Vargula tsujii, a new species of luminescent ostracod from lower and southern California (Myodocopa: Cypridininae). Proc. Biol. Soc. Wash. 90, 218–231 (1977).

Hammer, R. M. Day-night differences in the emergence of demersal zooplankton from a sand substrate in a kelp forest. Mar. Biol. 62, 275–280 (1981).

Stepien, C. A. & Brusca, R. C. Nocturnal attacks on nearshore fishes in southern California by crustacean zooplankton. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 25, 91–105 (1985).

Warner, J. A. & Case, J. F. The zoogeography and dietary induction of bioluminescence in the midshipman fish, Porichthys notatus. Biol. Bull. 159, 231–246 (1980).

Cohen, A. C. & Oakley, T. H. Collecting and processing marine ostracods. J. Crust. Biol. 37, 347–352 (2017).

Lee, K. H.-H. Genetic differentiation in Vargula tsujii (Ostracoda: Cypridinidae) along the California coast. (California State University, Los Angeles, 2002).

Paradis, E. pegas: an R package for population genetics with an integrated-modular approach. Bioinformatics 26, 419–420 (2010).

R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2019).

Jombart, T. adegenet: a R package for the multivariate analysis of genetic markers. Bioinformatics 24, 1403–1405 (2008).

Schwarz, G. Estimating the Dimension of a Model. Ann. Stat. 6, 461–464 (1978).

Vannier, J., Abe, K. & Ikuta, K. Feeding in myodocopid ostracods: functional morphology and laboratory observations from videos. Mar. Biol. 132, 391–408 (1998).

Schindelin, J. et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 676–682 (2012).

Garreta, R. & Moncecchi, G. Learning scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. (Packt Publishing Ltd, 2013).

van Rossum, G. Python tutorial (1995).

Weisenfeld, N. I., Kumar, V., Shah, P., Church, D. M. & Jaffe, D. B. Direct determination of diploid genome sequences. Genome Res. 27, 757–767 (2017).

Ogoh, K. & Ohmiya, Y. Complete mitochondrial DNA sequence of the sea-firefly, Vargula hilgendorfii (Crustacea, Ostracoda) with duplicate control regions. Gene 327, 131–139 (2004).

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359 (2012).

Nurk, S. et al. Assembling genomes and mini-metagenomes from highly chimeric reads. Lecture Notes in Computer Science 158–170 (2013).

Wick, R. R., Schultz, M. B., Zobel, J. & Holt, K. E. Bandage: interactive visualization of de novo genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 31, 3350–3352 (2015).

Camacho, C. et al. BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 10, 421 (2009).

Priyam, A. et al. Sequenceserver: A modern graphical user interface for custom BLAST databases. Mol. Biol. Evol. 36, 2922–2924 (2019).

Robinson, J. T. et al. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 24–26 (2011).

Shen, W., Le, S., Li, Y. & Hu, F. SeqKit: A cross-platform and ultrafast toolkit for FASTA/Q file manipulation. PLoS One 11, e0163962 (2016).

Walker, B. J. et al. Pilon: an integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PLoS One 9, e112963 (2014).

Bernt, M. et al. MITOS: Improved de novo metazoan mitochondrial genome annotation. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 69, 313–319 (2013).

Jeffery, N. W., Ellis, E. A., Oakley, T. H. & Ryan Gregory, T. The genome sizes of ostracod crustaceans correlate with body size and evolutionary history, but not environment. J. Hered. 108, 701–706 (2017).

Cohen, A. C. & Morin, J. G. Patterns of reproduction in ostracodes: A review. J. Crust. Biol. 10, 184 (1990).

Steele, D. H. & Steele, V. J. Egg size and duration of embryonic development in Crustacea. Int. Rev. ges. Hydrobiol. Hydrograph. 60, 711–715 (1975).

Wakayama, N. Embryonic development clarifies polyphyly in ostracod crustaceans. J. Zool. 273, 406–413 (2007).

Lewis, S. M. & Cratsley, C. K. Flash signal evolution, mate choice, and predation in fireflies. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 53, 293–321 (2008).

Deheyn, D. D. Bioluminescence in the brittle star Amphiolis squamata (Echinodermata): an overview of 10 years of research. In Bioluminescence and Chemiluminescence https://doi.org/10.1142/9789812811158_0009 (2001).

Houliston, E., Momose, T. & Manuel, M. Clytia hemisphaerica: a jellyfish cousin joins the laboratory. Trends Genet. 26, 159–167 (2010).

Boissin, E., Hoareau, T. B., Féral, J. P. & Chenuil, A. Extreme selfing rates in the cosmopolitan brittle star species complex Amphipholis squamata: data from progeny-array and heterozygote deficiency. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 361, 151–159 (2008).

Heip, C. The life-cycle of Cyprideis torosa (Crustacea, Ostracoda). Oecologia 24, 229–245 (1976).

Martens, K. Effects of temperature and salinity on postembryonic growth in Mytilocypris henricae (Chapman) (Crustacea, Ostracoda). J. Crust. Biol. 5, 258–272 (1985).

Viviani, V. R. Fireflies (Coleoptera: Lampyridae) from southeastern Brazil: Habitats, life history, and bioluminescence. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 94, 129–145 (2001).

Ho, J.-Z., Chiang, P.-H., Wu, C.-H. & Yang, P.-S. Life cycle of the aquatic firefly Luciola ficta (Coleoptera: Lampyridae). J. Asia. Pac. Entomol. 13, 189–196 (2010).

Fu, X., Nobuyoshi, O., Vencl, F. V. & Lei, C. Life cycle and behaviour of the aquatic firefly Luciola leii (Coleoptera: Lampyridae) from mainland China. Can. Entomol. 138, 860–870 (2006).

Soong, K., Lin, Y., Chao, S. & Chang, D. Spawning time of two shallow-water brittle stars. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 376, 165–171 (2009).

Hagman, D. K. & Vize, P. D. Mass spawning by two brittle star species, Ophioderma rubicundum and O. Squamosissimum (Echinodermata: Ophiuroidea), at the Flower Garden Banks, Gulf of Mexico. Bull. Mar. Sci. 72, 871–876 (2003).

Rivers, T. J. & Morin, J. G. Female ostracods respond to and intercept artificial conspecific male luminescent courtship displays. Behav. Ecol. 24, 877–887 (2013).

Stern, D. L. & Orgogozo, V. Is genetic evolution predictable? Science 323, 746–751 (2009).

Boake, C. R. B. et al. Genetic tools for studying adaptation and the evolution of behavior. Am. Nat. 160(Suppl 6), S143–59 (2002).

Ritchie, M. G. Sexual selection and speciation. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol.Syst. 38, 79–102 (2007).

Yeh, H.-W. & Ai, H.-W. Development and applications of bioluminescent and chemiluminescent reporters and biosensors. Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem. 12, 129–150 (2019).

Cong, L. et al. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science 339, 819–823 (2013).

Krzywinski, M. et al. Circos: an information aesthetic for comparative genomics. Genome Res. 19, 1639–1645 (2009).

Pang, K. & Martindale, M. Q. Mnemiopsis leidyi spawning and embryo collection. CSH Protoc. 2008, db.prot5085 (2008).

Warren, K. J. The establishment and characterization of primary cell cultures derived from the ctenophore Mnemiopsis leidyi. (University of Miami, 2016).

Baker, L. D. & Reeve, M. R. Laboratory culture of the lobate ctenophore Mnemiopsis mccradyi with notes on feeding and fecundity. Mar. Biol. 26, 57–62 (1974).

Kahn, B. Scientists Have Cultivated a Mesmerizing Jelly That’s Like ‘Barely Organized Water’. Earther https://earther.gizmodo.com/scientists-have-cultivated-a-mesmerizing-jelly-thats-li-1823207295 (2018).

Lindner, A. & Migotto, A. E. The life cycle of Clytia linearis and Clytia noliformis: metagenic campanulariids (Cnidaria: Hydrozoa) with contrasting polyp and medusa stages. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. U. K. 82, 541–553 (2002).

Delroisse, J., Ortega-Martinez, O., Dupont, S., Mallefet, J. & Flammang, P. De novo transcriptome of the European brittle star Amphiura filiformis pluteus larvae. Mar. Genomics 23, 109–121 (2015).

Oba, Y. et al. Bioluminescence of a firefly pupa: involvement of a luciferase isotype in the dim glow of pupae and eggs in the Japanese firefly, Luciola lateralis. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 12, 854–863 (2013).

Meyer-Rochow, V. B. Glowworms: a review of Arachnocampa spp. and kin. Luminescence 22, 251–265 (2007).

Maheswarudu, G. & Vineetha, A. Culture of the littoral oligochaete Pontodrilus bermudensis Beddard. J. Bioprocess Tech. 97, 142–155 (2013).

Nishida, H. Development of the appendicularian Oikopleura dioica: culture, genome, and cell lineages. Dev. Growth Differ. 50(Suppl 1), S239–56 (2008).

Martí-Solans, J. et al. Oikopleura dioica culturing made easy: a low-cost facility for an emerging animal model in EvoDevo. Genesis 53, 183–193 (2015).

Acknowledgements

We thank the USC Wrigley Institute for Environmental Studies for transportation and use of the facilities at the Wrigley Marine Science Center on Catalina Island, CA. J.D.M. worked on the project at Wrigley during the Catalina Marine Biology Semester hosted by California State University of Long Beach and with support from the NSF (Award DEB·1457462 to E.T.). J.A.G. was supported by the NSF (PRFB Award: 1711201). Population genetic work was supported by a mini-grant from Cal State L.A. to E.T.; sequence data were obtained from the Masters thesis of K.H. Lee; DM Jacinto and E Stiner helped with collections throughout California; R.M. Serrano helped with measurements of some specimens; N. Hensley contributed data on collecting locations. Genomic sequencing was supported by the Beckman Young Investigator Award to J.K.W. from the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Foundation and by a UCSB Faculty Seed Grant to T.H.O. Finally, we would like to thank Simone Brandão and two anonymous reviewers for their comments on our manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.A.G., E.T., J.K.W., and T.H.O. conceived of and designed the study; J.A.G., G.M., M.N.B., M.S.D., J.D.M., T.R.F., and D.T.S. contributed to the acquisition and analysis of the data in this study; all authors participated in the interpretation of data, helped draft or substantially revise the manuscript, and gave final approval for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplemenatry information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Goodheart, J.A., Minsky, G., Brynjegard-Bialik, M.N. et al. Laboratory culture of the California Sea Firefly Vargula tsujii (Ostracoda: Cypridinidae): Developing a model system for the evolution of marine bioluminescence. Sci Rep 10, 10443 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-67209-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-67209-w

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.