Abstract

Candida albicans is a major cause of human infections, ranging from relatively simple to treat skin and mucosal diseases to systemic life-threatening invasive candidiasis. Fungal infections treatment faces three major challenges: the limited number of therapeutic options, the toxicity of the available drugs, and the rise of antifungal resistance. In this study, we demonstrate the antifungal activity and mechanism of action of peptides ToAP2 and NDBP-5.7 against planktonic cells and biofilms of C. albicans. Both peptides were active against C. albicans cells; however, ToAP2 was more active and produced more pronounced effects on fungal cells. Both peptides affected C. albicans membrane permeability and produced changes in fungal cell morphology, such as deformations in the cell wall and disruption of ultracellular organization. Both peptides showed synergism with amphotericin B, while ToAP2 also presents a synergic effect with fluconazole. Besides, ToAP2 (6.25 µM.) was able to inhibit filamentation after 24 h of treatment and was active against both the early phase and mature biofilms of C. albicans. Finally, ToAP2 was protective in a Galleria mellonella model of infection. Altogether these results point to the therapeutic potential of ToAP2 and other antimicrobial peptides in the development of new therapies for C. albicans infections.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Candida albicans is a fungal species present in the normal human microbiota, colonizing several areas of the body. However, under certain circumstances, this species may become a pathogen, causing diseases that can be life-threatening1,2,3,4. The use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, immune suppression, or changes in the local host environments are examples of situations that may favor the proliferation of C. albicans and the onset of disease5,6,7,8. Moreover, C. albicans ability to thrive in human tissues involves metabolic and morphological changes associated with the expression of different virulence factors9.

C. albicans virulence factors include secretion of enzymes, adhesion to cell surfaces and evasion of the immune system10,11. Two virulence factors of major clinical importance are the fungal polymorphism and its ability to form biofilms12,13,14. C. albicans ability to transit between yeast and filamentous forms is crucial for pathogenesis and both fungal forms are relevant for infection15. For instance, hyphae have a major role on tissue invasion, whereas the yeast morphology facilitates fungal dispersion16. The different fungal morphologies are also important for the formation of C. albicans biofilms17. Living in biofilms confers to the microorganisms several advantages, when compared to the planktonic lifestyle, including protection against immune cells, increased resistance to antimicrobials agents and other chemical, physical and environmental stressors18,19.

The number of antifungals currently available for clinicians is limited and the scenario is worsened by the rise of antifungal resistance to available drugs such as azoles, polyenes and echinocandins20,21. For example, C. albicans biofilms present resistance to fluconazole6,22, one of the most commonly used agents in the treatment of mucosal and superficial candidiasis23. In addition to resistance, many of the current systemic antifungal drugs are also toxic to host cells often producing important side effects. Altogether these factors stress the need of new therapeutic strategies against candidiasis and other mycoses20.

Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) have been considered a promising alternative for the prevention and treatment of different infectious diseases24,25,26,27. AMPs are small, low-molecular-weight cationic peptides that are part of the innate immune response of the great majority of organisms28,29,30. In addition to their antimicrobial activity, natural and synthetic AMPs can also be immunomodulatory, modulating inflammation, chemotaxis and immune cell differentiation31,32,33. AMPs have been shown to be effective against bacteria, fungi, viruses and protozoa and are less prone to induce resistance because of their multiple cellular targets34,35,36,37.

Our group identified AMPs derived from a scorpion venom cDNA library presenting activities against different Candida spp and C. neoformans. Based on their potential antifungal activities, cationic antimicrobial peptides ToAP2, from a cDNA library of the scorpion Tityus obscurus venom gland (Uniprot entry LT576030); and NDBP-5.7, from a cDNA library of the scorpion Opisthacanthus cayaporum venom gland (Uniprot entry C5J886) were synthetized for further characterization in this work. ToAP2 (26 residues of amino acid, net charge +6) and NDBP-5.7 (13 residues of amino acid, net charge +1) presented MIC of 12.5 µM (37.5 µg/ml) and 25 µM (35.8 µg/ml) for C. albicans planktonic cells, respectively38. In addition, both are non-disulfide-bridged peptides (NDBP) belonging to NDBP subfamilies 3 and 5, respectively, according to the classification proposed by Zeng et al.39, who grouped scorpion NDBPs, in six subfamilies based on their pharmacological action, length and structural similarity. In this work we explored their mechanisms of action against C. albicans planktonic and biofilm cells and their activity in combination with two important antifungals, fluconazole and amphotericin B.

Results

Minimal inhibitory concentrations (MIC) for C. albicans

We have already evaluated the MIC of ToAP2 and NDBP-5.7 against C. albicans SC-5314 in our previously work using an inoculum of 2 × 103 cells/mL. However, some assays described in this work, such as flow cytometry and Electron Transmission Microscopy (TEM), required a higher cell density or a non-filamenting strain. To solve the filamentation problem for the flow cytometry analysis, we used the non-filamenting strain SSY50-B40, which showed the same MIC values to both AMPs presented by the filamenting strain SC-5314 (12.5 µM for ToAP2 and 25 µM for NDBP-5.7)38. In addition to that, we evaluated ToAP2 and NDBP-5.7 MIC for both C. albicans strains at a cell density of 1 × 106 cells/mL. The obtained MIC was also the same for both strains (25 µM for ToAP2 and 100 µM for NDBP-5.7).

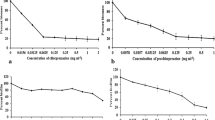

ToAP2 and NDBP-5.7 permeabilize C. albicans cell membrane

Plasma membrane integrity of C. albicans non-filamenting strain SSY50-B40 treated with both peptides was evaluated by flow cytometry using PI (Fig. 1). Both peptides led to a dose-dependent increase in the percentage of permeabilized cells. Concentrations of ToAP2 from 12.5 μM (subMIC) to 25 μM (MIC) produced an increase of respectively 42.1% to 65.8% in the proportion of permeabilized cells in comparison to the control (Fig. 1A). While the treatment with 50 μM (subMIC) and 100 µM (MIC) of NDBP-5.7 increased the percentage of permeabilized cells in 66,87% and 88,97%, respectively (Fig. 1B). Figure 1C compares live and dead cells in the presence of PI showing that only the dead cells emit the fluorescent signal.

Flow cytometry analysis of C. albicans (SSY50-B strain) cell membrane integrity after treatment with ToAP2 and NDBP-5.7. After 2 h of treatment with ToAP2 (A) or NDBP-5.7 (B) at MIC and Sub-MIC concentrations the uptake of propidium iodide by fungal cells was measured by flow cytometry. Untreated cells were used as a control. The horizontal line indicates the PI-positive gate (C). Fluorescence microscopy of dead (ethanol permeabilized) and live cells (untreated) in the presence of PI. Scale bars 20 µm.

ToAP2 alters the ultrastructure of C. albicans

The ultrastructure of C. albicans cells treated with AMPs ToaP2 and NDBP-5.7 was evaluated by transmission electron microscopy. Control samples revealed cells with preserved morphology and cell shape surrounded by a regular cell wall and continuous cell membrane. These cells also presented a homogeneous cytoplasm with nucleus, mitochondria and other membrane-enclosed organelles (Fig. 2A,B). On the other hand, ToAP2 treated cells show several ultrastructure alterations, including an irregular thickness and shape of the cell wall, regions of discontinuity of the cell wall and cell membrane and an amorphous and diffuse cytoplasm lacking a clear organization of organelles (Fig. 2D,E). This could suggest that in addition to the cell membrane, this peptide could be also acting on intracellular membranes. In contrast, cells treated with NDBP-5.7 displayed a more regular morphology, especially at the cell wall organization (Fig. 2G,H), although we could also observe some cells showing an irregular cytoplasm filled with a large number of tiny vacuoles (Fig. 2H). Interestingly, we could also observe a very distinguishable cell wall fibrillar outer layer in NDBP-5.7 treated cells that was not clear in the control cells.

TEM and AFM images of C. albicans untreated and treated cells with ToAP2 and NDBP-5.7 at sub-inhibitory concentrations. (A–C) control cells; (D–F) and (G–I) ToAP2 and NDBP-5.7 treated cells, respectively. TEM images are indicated by the letters (A,B,D,E,G,H) and AFM by the letters (C,F,I). Scale bars = 1 µm (A,B,D,G) and 0.5 µm (E,H). Red arrows indicate regions of discontinuity of the cell wall/cell membrane. White square regions indicate accumulation of tiny vacuoles. Black square region – indicates the fibrillar material at the cell wall of NDBP-5.7-treated cells. CW – Cell wall, Mt – Mitochondria, N – Nucleus, Ct – Cytoplasm, V -Vacuole.

ToAP2 and NDBP-5.7 induce morphological changes in C. albicans cells at subinhibitory concentrations

We used atomic force microscopy to visualize possible alterations in C. albicans cell surface or morphology induced by a 24 h treatment with both peptides. Control cells not exposed to any of the AMPs showed the typical oval and well-defined morphology and a smooth surface. Treatment with sub-inhibitory concentration of ToAP2 (6.25 μM) and NDBP-5.7 (25 μM) resulted in C. albicans cells with altered cell morphologies in comparison to control cells (Fig. 2C). In overall, the most noticeable changes in ToAP2-treated were deformations in their area including flattened regions in their surface instead of the round morphology observed in the control cells. On the other hand, NDBP-5.7-treated cells had a wrinkled appearance with significant increase in cell-surface deformations (Fig. 2F,I). Results from both microscopy approaches combined with the results of the membrane permeability assay suggest that the cell surface is probably a target for both AMPs.

ToAP2 inhibits C. albicans filamentation

Sub-inhibitory concentrations of ToAP2 (6.25 and 3.12 μM) and NDBP-5.7 (12.5 and 25 μM) were used to evaluate their effect on C. albicans SC 5314 filamentation during 4 h or 24 h treatments. There was no difference in the percentage of fungal cells with filaments or in the germ-tube lengths in comparison to the control at the early time points (Fig. 3A,B). In contrast, there was a decrease in fungal filamentation after 24 h of treatment with ToAP2 (Fig. 3C). Considering that filamenting cells normally grow in clumps, impairing the evaluation of the size of individual cells or the number of individuals cells in a clump at later time points, we complement the microscopic analysis presented in Fig. 3C by time-lapse microscopy of cells submitted to the different treatments along 24 h (Supplementary Movie S1). At MIC concentrations we observed very little cell filamentation in response to both peptides, probably because the cells are dying. Interestingly, the treatment with 6.25 μM of ToAP2 not only delayed C. albicans filamentation, but also decreased de overall length of the filaments in comparison to the control, apparently without any major effect on cell viability (Supplementary Movie S1). Although NDBP-5.7 apparently have not affected the filamentation on the tested conditions, at the second half of the Supplementary Movie S1, we can still see several yeast cells lacking germ-tubes.

Effects of ToAP2 and NDBP-5.7 on C. albicans filamentation. (A) Percentage of filamenting cells during 4 h of treatment with different concentrations of ToAP2 or NDBP-5.7. (B) Length of C. albicans filamenting cells after 3 h of treatment with ToAP2 or NDBP-5.7. (C) Bright field microscopy of the effects of ToAP2 and NDBP-5.7 on C. albicans filamentation after 24 h treatment. Mean ± SEM (p ≤ 0.05). Scale bars 100 µm.

Combined action of antifungal drugs with ToAP2 and NDBP-5.7

The combined activity of antifungal agents and AMPs was evaluated using a Checkerboard assay41, based on the MIC concentrations of each AMP38.

The results revealed that ToAP2 (3.12 µM for the assays with fluconazole or 0.78 µM for the assay with amphotericin B) presented a synergistic effect when combined with fluconazole (0.25 µM) and amphotericin B (0.13 µM), with FIC indices of 0.5 and 0.182, respectively. NDBP-5.7 (1.56 µM) was also synergic with amphotericin B (0.13 µM) showing a ΣFIC of 0.182), but only additive with fluconazole (ΣFIC of 0.562). In the association between the peptides, the best combination of ToAP2 (6.25 µM) with NDBP-5.7 (6.25 µM) showed only additive effect (Table 1).

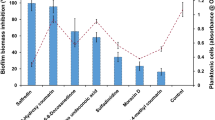

ToAP2 is effective in different stages of biofilm formation

We evaluated the effects of ToAP2 and NDBP-5.7 at early-phase (after 4 h of attachment) and mature biofilms (after 24 h of attachment). Treatment with amphotericin B concentrations equal or higher than 0.27 μM produced an inhibition of at least 75% in the viability of early-phase biofilms. Although the effects were less pronounced, the three highest concentrations of amphotericin also produced a 40–60% inhibition of mature biofilms. (Fig. 4A,B). In contrast, fluconazole had no activity at any of the tested concentrations at both phases of biofilm formation (Fig. 4C,D).

Effects of ToAP2 and NDBP-5.7 on the viability of early phase (4 h) or mature (24 h) C. albicans biofilms. C. albicans biofilms previously grown for 4 h (A,C,E,G) or 24 h (B,D,F,H) were treated for 24 h with different concentrations of amphotericin B (A,B), fluconazole (C,D), ToAP2 (E,F) or NDBP-5.7 (G,H). After that, cell viability was evaluated using the alamarBlue reduction assay. Results were expressed as a mean of three independent assays. P-value indicates statistical difference using the Tukey post-test. The results represent mean ± SEM.

ToAP2 displayed significant antimicrobial activity against both early-phase (p = <0.0001) and mature biofilm phases (p = <0.0001) (Fig. 4E,F). Starting with 25 μM of ToAP2 we observed a dose dependent inhibition of early phase biofilms ranging from 60.02 to 99.85%. ToAP2 also produced a 97.02% decrease in the viability of mature biofilms, but only at 200 μM. On the other hand, NDBP-5.7 peptide showed no activity in either phases of C. albicans biofilms (Fig. 4G,H). The viability of biofilms after any of the treatments was also evaluated by fluorescence microscopy using the viability dye Phloxine B (Supplementary Figs. S2 and S3).

Peptides ToAP2 and NDBP-5.7 permeabilize the membrane of biofilm cells

Membrane integrity of C. albicans biofilm cells treated with ToAP2 or NDBP-5.7 was evaluated using an adaptation of the fluorophore Rhodamine 6G efflux assay as described before42. Both peptides produced a dose-dependent increase in permeabilization of C. albicans biofilm cells at both phases of biofilm formation. There was an increase in the permeabilization of C. albicans early-phase biofilm cells with concentrations of 25–6.25 µM of ToAP2 and of 100–25 µM of NDBP-5.7 (Fig. 5A; p = 0.0002). Similarly, we observed an increase in the permeabilization of mature biofilm cells after treatments with concentrations of 100–25 µM of either ToAP2 or NDBP-5.7 (Fig. 5B; p = <0.0001). Neither amphotericin B (1.08 µM) or fluconazole (52 µM) displayed significant differences in the permeabilization of biofilm cells compared to the untreated control at the tested concentrations.

Effects of AMPs on the membrane integrity of C. albicans biofilm cells. Alterations in membrane permeability was evaluated using an adaptation of the Rhodamine 6G efflux assay after 24 hours of treatment with different concentrations of ToAP2 and NDBP-5.7 in early phase (A) or mature biofilm (B). Untreated cells and cells treated with fluconazole or amphotericin B were used as a control. P-value indicates statistical difference by Tukey post-test (****p ≤ 0.0001; ***p ≤ 0.001; **p ≤ 0.01; *p ≤ 0.05). Mean ± SEM.

Effect of ToAP2 on the survival of Galleria mellonella infected with C. albicans

The ToAP2 toxicity and antimicrobial activity in vivo was evaluated using the G. mellonella model. For the toxicity evaluation different groups of larvae were injected with 10, 20 and 40 mg ToAP2/kg or with 2 mg/kg of Amphotericin B. None of the AMP doses were toxic to G. mellonella (data not shown). In vivo antimicrobial activity of ToAP2 was evaluated after infecting different groups of larvae with C. albicans and treating the groups with different doses of this peptide. All doses of ToAP2 resulted in an increased survival of the larvae when compared to control group (treated with PBS) (Fig. 6A). Doses of 10, 20 and 40 mg/kg resulted in an increased survival rate of 18.7, 31.2 and 25% respectively. ToAP2 doses of 20 and 40 mg/kg resulted in survival rates not statistically different when compared to 2 mg/kg of Amphotericin B, which increased larvae survival to 50%. In the larvae group treated with PBS (control group), all organisms died in the third day after C. albicans infection.

ToAP2 Effects on G. mellonella infected with C. albicans. (A) Survival curve of G. mellonella infected with C. albicans and treated with amphotericin B or different concentrations of ToAP2 (A). Histopathology of C. albicans infection in the G mellonella model. After 1 h of infection, the larvae were treated with doses of ToAP2 at 40 mg/kg (E,F) and Amphotericin at 2 mg/Kg (G,H). Uninfected (B) and untreated (C,D) larvae were used as controls. Panel H is a higher magnification of the region depicted on panel G. Black arrows indicate the presence of foci of C. albicans. Figure B, C, E and G scale bar 100 µm; Figure D, F and H scale bar 20 µm. Graphics were generated from two independent assays using Kaplan-Meier survival curves. The squares in panels E and F indicate fungal cells.

ToAP2 treatment decreases fungal burden of G. mellonella larvae infected with C. albicans

To evaluate the in vivo effects of ToAP2 we performed histopathology analysis of G. mellonella larvae infected with C. albicans and treated with this peptide, amphotericin B or PBS (untreated control). Non-infected larvae were used as control (Fig. 6A). Infected and untreated larvae (Fig. 6B) revealed dissemination of C. albicans yeast and hyphae cells throughout various parts of the organism (Fig. 6C,D). Larvae treated with either 40 mg/kg ToAP2 (Fig. 6E,F) or 2 mg/kg of Amphotericin (Fig. 6G,H) showed fewer foci of infection with lower number of fungal cells and most of them in the yeast morphology, although the effects were more accentuated after amphotericin B treatment.

Discussion

The structural and physiological similarity between fungal and mammalian cells makes the development of new antifungals a complex challenge43. Given this, the AMPs are small conserved molecules part of the innate immune response of several organisms and a promising group of new antimicrobial agents44. In the present work, we further evaluated the antifungal activity of two AMPs previously described and partially characterized by our group, ToAP2 and NDBP-5.7. We analyzed the activity of both AMPs on membrane integrity, cell morphology, yeast-to-hypha transition, and biofilm formation of C. albicans.

Flow cytometry analysis of propidium iodine labeled cells revealed that treatment with both peptides produced a dose-dependent increase in membrane permeability and cell death. A similar permeabilization of C. albicans cells was previously described after treatment with Cathelicidin PMAP-36 analogues45. AFM and TEM results also suggested the induction of membrane damage and loss of cell surface integrity by both peptides, particularly by ToAP2. AFM images of fungal cells treated with ToAP2 and NDBP-5.7 showed morphological alterations including the loss of the typical oval shape and an increase in surface roughness, when compared to untreated control cells. Those cell deformations might be linked to leakage of cellular contents as a result of cell membrane damage. Comparable effects were observed in other AFM studies describing alterations in C. albicans cell morphology and membrane integrity when in the presence of antimicrobial peptides Psd146 and LL-3747. TEM of C. albicans treated with ToAP2 revealed several cells showing a loss of cell wall integrity and presenting an internal amorphous cytoplasm with mostly no distinguishable organelles, suggesting that this AMP can induce damage not only on the plasma membrane but also in the membrane of cellular organelles inducing loss of integrity of those structures. These alterations bear similarities to the ones produced by the treatment of C. albicans cells with the phosphorylated peptide K40H derived from the constant region of human IgMs48 or with the antifungal peptide AMP MCh-AMP1 derived from chamomille (Matricaria chamomilla)49.

These observations suggest that membrane damage and permeabilization is one of the mechanisms of action of those molecules as previously reported for many antimicrobial peptides50,51. Our findings are also in agreement with previously published circular dichroism analyses showing ToAP2 and NDBP-5.7 tendency to form α-helix structures38, a common feature in other antimicrobial peptides targeting microbial cell membranes52,53,54. However, we cannot exclude other mechanisms of action for these molecules, as AMPs have been shown to have multiple antifungal actions such as DNA damage, inhibition of protein synthesis or metabolic pathways and induction of apoptosis or oxidative stress in addition to membrane permeabilization50,51.

An important factor associated to C. albicans pathogenesis is its ability to perform yeast-to-hypha transition8. An alternative therapeutic approach for infectious diseases is targeting microbial virulence attributes, what would increase microbial susceptibility to antimicrobials or to the immune system components with lower chances of inducing microbial resistance55. As a result, many research groups have dedicated efforts in the search of molecules that could inhibit C. albicans filamentation56,57,58.

As shown in Fig. 3, subinhibitory concentrations of both AMPs presented no effect on the percentage of C. albicans cells presenting germ tubes formation during the first four hours of treatment. However, a prolonged incubation with 6.25 µM of ToAP2 significantly delayed filamentation and reduced the number of cells presenting germ tubes without killing the cells (Fig. 3C). It is important to notice that filamentation is a complex process dependent of many different factors, such as availability of nutrients and the presence of serum in the medium, and all of them can interfere with the peptide inhibitory effects59.

ToAP2 showed the most promising antimicrobial effects in most of our assays. However, as other AMPs60,61, this peptide presents some toxicity to mammalian cells in concentrations close to its MIC for C. albicans and other tested fungi38. One approach to overcome this problem is the optimization of this peptide sequence aiming to decrease its toxicity to mammalian cells/enhance its antimicrobial activity. Another approach could be the combined use of AMPs with conventional antifungals. The use of drug combinations is a strategy to improve drug’s efficacy reducing their concentrations to non-toxic levels and at the same time a strategy to decrease resistance development62.

Thus, we evaluated the combined actions of ToAP2 and NDBP-5.7 with each other and with amphotericin B or fluconazole against planktonic cells of C. albicans. The combination of ToAP2 and NDBP-5.7 AMPs showed an additive effect, while both peptides presented a synergistic effect with amphotericin B and ToAP2 also with fluconazole (Table 1). In all tested combinations, the active concentrations used were reduced in comparison with the MIC of each of the compounds alone38. For instance, the combination of AMPs with amphotericin B produced a reduction of up to 4X in their MIC. Our results were similar to those found by Lum et al.63, who found that the combination of antimicrobial peptides with amphotericin B resulted in a synergistic effect, while the combination between peptides was additive or indifferent in C. albicans infection models. The peptides MUC7 12-mer, hepcidin 20 and defensin HsAFP1 have also shown synergism with antifungal drugs64,65,66,67. Our results might also suggest that ToAP2 and NDBP-5.7 act on different targets than the antifungal agents, thus their complementary effect as previously suggested for other AMPs68. According to Gray and colleagues69, the main mechanism of action of Amphotericin B in yeast cells (Saccharomyces cerevisiae and C. albicans) is the binding and sequestration of ergosterol, while membrane permeabilization is a secondary mechanism not necessarily required for its fungicidal effects. In addition to its activities at the membrane level, another important microbicidal activity of amphotericin B is the induction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation observed in many fungal species. It is believed that this mechanism could be related to the low induction of fungal resistance to this compound70. On the other hand, fluconazole, a fungistatic azole, interacts with a key enzyme in fungal sterol biosynthesis inhibiting the synthesis of ergosterol and compromising membrane permeability and fluidity71. Microbial cell membrane is also regarded as the primary target of AMPs, being membrane permeabilization probably by pore formation one of the main effects of those molecules. Our flow cytometry and microscopy results point to the same happening in C. albicans cells treated with NDBP-5.7 and ToAP2. However, as we mentioned before, we cannot exclude other mechanisms of actions for those molecules and further studies are needed to elucidate the mechanisms behind the synergistic effects we have observed.

Compared to planktonic cells, biofilms can be up to 1000 times more resistant to antimicrobials, due to certain factors such as the presence of a dense extracellular matrix, changes in cell metabolism and the positive regulation of efflux pumps among others72,73,74. Consequently, few antimicrobials capable of treating biofilm-related infections are available today75. Our results indicate that ToAP2 presented inhibitory action on both phases of biofilm formation. Amphotericin B but not fluconazole was also active in our tests, as previously reported63,76,77,78,79.

Biofilm resistance to fluconazole could be partially explained by the presence of the extracellular matrix, composed by proteins, polysaccharides, nucleic acids and lipids, which serves as a barrier for antifungals80,81. It has been reported that β-1,3 glucan, present in C. albicans biofilm matrix, can hijack triazoles preventing these drugs from reaching cell membrane82,83. Both ToAP2 and NDBP-5.7 were able to permeabilize C. albicans biofilm cell membrane in both phases of biofilm formation (Fig. 5A,B). Interestingly, NDBP-5.7 affected membrane permeabilization without decreasing the viability of the biofilm (Fig. 4G,H).

We have shown that ToAP2 was not lethal to G. mellonella larvae when used at concentrations up to 40 mg/kg, similar to what was observed with AMPs hMUC7–12, hLF(1–11), DsS3(1–16) by Maccalum et al.64. ToAP2 doses of 10, 20 and 40 mg/kg were also able to significantly increase larva survival after C. albicans infections in our assays. At the two highest concentrations of this AMP the larva survival profile was similar to what we observed with the amphotericin B treatment. Although amphotericin B effects were more pronounced, histopathological analysis of larvae infected with C. albicans and treated with any of the two compounds resulted in a reduction in the number of foci of infection and a more limited infection in contrast with the disseminated form observed in the control (Fig. 6). In addition, in the control groups, we observed the presence not only of yeast cells as in the treated-groups, but also filament cells possibly indicating C. albicans tissue invasion as described before84. These results are also in accordance to previously described works showing the efficacy of antifungals in the treatment of G. mellonella infected with C. albicans85,86,87. Finally, the results observed with ToAP2 indicated a possible systemic action of this peptide in this in vivo infection model.

In conclusion, we have shown that the peptides ToAP2 and NDBP-5.7 are active against planktonic and biofilms of C. albicans. Treatment with these peptides increased cell permeability and generated important morphological alterations in C. albicans cells. ToAP2 showed the most promising antimicrobial effects in most of our assays an can be considered a putative candidate for new antifungal formulations, especially for topical treatments or to be used in combined therapeutic strategies. The observed synergy of this peptide with fluconazole and amphotericin B is particularly encouraging because we could observe an increase in the efficacy of both molecules decreasing their active concentrations and probably also their toxicity to mammalian cells.

Invasive candidiasis affects around 750 thousand people yearly. This disease has a close association with health-care environment where is a major cause of morbidity and mortality specially among elderly and premature babies88,89. As for other invasive fungal infections the available therapeutic options are extremely limited and associated with high toxicity, costs and the increase in fungal strains resistant to the few antifungal drugs currently available, such echinocandins and azoles90,91,92,93.

The results described in this work are promising in view of the urgent need for alternative antifungal molecules to treat systemic mycoses and to prevent the development of fungal resistance. Currently, we are working on the design and optimization of the antimicrobial features of ToAP2, aiming to circumvent its cytotoxicity against mammalian cells and to increase the biological properties reported here.

Material and methods

Synthesis of antimicrobial peptides

ToAP2 (FFGTLFKLGSKLIPGVMKLFSKKKER) and NDBP-5.7 (ILSAIWSGIKSLF-NH2) sequences are derived from cDNA libraries made from the venom glands of Tityus obscurus and Opisthacanthus cayaporum scorpions38. The AMPs were chemically synthesized by Biomatik using an Fmoc / t-butyl on solid support strategy. Peptide purification, characterization and purity evaluation were performed as previously described by Guilhelmelli38.

Fungal culture conditions

C. albicans strain SC 5314 was used in most assays, except in the experiments of flow cytometry and Atomic Force Microscopy. In these assays we used the non-filamenting strain C. albicans SSY50-B, kindly provided by Stephen P. Saville and José L. Lopez-Ribot40. Fungal cells from frozen stocks were grown in Sabouraud dextrose broth for 18 h at 30 °C and 200 rpm. After that, cells were harvested by centrifugation (1000 g at 25 °C), washed three times in sterile phosphate buffer (PBS), counted in a hemocytometer and diluted to the appropriate cell densities.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) evaluation

As previously described by our group38, all antifungal assays were carried out according to guidelines of the broth microdilution susceptibility test by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) M27-A3 with some modifications94. Briefly, cells suspensions of C. albicans cells at 2 × 103 cells/mL were tested using concentrations of 100 to 0.78 µM of each AMP. The criterium to define the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) was the lowest AMP concentration that completely inhibited visible fungal growth at the end of the incubation period. All assays were done in biological triplicates performed on separate dates.

Before performing assays requiring a higher number of cells, such as the evaluation of cell membrane integrity or microscopic analyses, we determined the MIC for C. albicans suspensions at the cell density used in those experiments - 1 × 106 cells/mL. Therefore, the higher MIC values for all antifungals in those assays.

Evaluation of cell membrane integrity

An inoculum of 500 µl of 1 × 106 cells/mL of C. albicans SSY50-B strain was added to RPMI medium in the presence or absence of different concentrations of ToAP2 or NDBP 5.7 and incubated in a shaker at 37 °C and 200 rpm for 90 minutes45. Afterwards, the cultures were incubated with 1 μg/mL propidium iodide (PI) for an additional 30 minutes, in the dark, at 37 °C. The cells were then analyzed on a BD FACSVerse flow cytometer (minimum of 20,000 events per sample). The resulting data was analyzed using the FlowJo X software. The gating strategy consisted of: a) gating on fungal cells on a forward scatter (area) x side scatter (area) plot and b) doublet exclusion by gating on a forward scatter (width) x forward scatter (height) plot. Live untreated cells, and 70% ethanol-treated (dead) cells were also incubated with PI and used as controls. The cells were observed in an inverted microscope (Axio Observer Z1 Carl Zeiss Microscopy, USA) (excitation: 546/12 nm; emission: 607/80 nm).

Evaluation of ultrastructure by Transmission electronic microscopy

An inoculum of 1 × 106 cells of C. albicans SSY50-B strain was added to RPMI with concentrations of 25 and 50 µM of ToAP2 and NDBP-5.7 respectively following standard protocol with modifications45. After 24 h, the cells were washed with PBS and cell suspensions were fixed by immersion in 2.5% glutaraldehyde and 2% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) solution for 2 days. After washing, the cells were post-fixating with 2% osmium tetroxide in 0.1 M sodium cacodylate buffer and incubated overnight with 1% uranyl acetate after a new wash. Then the cells were dehydrated in graded series of ethanol and soaked in Epon (EMS). The blocks were cut at 50 nm on a RMC Ultramicrotome (PowerTome, USA) and recovered into 200 mesh copper grids, followed by double contrast method with 2% uranyl acetate. Visualization was performed at 80 kV in a JEOL JEM 1400 microscope (Japan) and digital images were acquired using a CCD digital camera Orious 1100 W (Tokyo, Japan).

Morphological analysis by atomic force microscopy (AFM)

Morphological evaluation was performed as described by Rodrigues de Araujo95 with modifications. An inoculum of 100 µL of 1 × 104 cells/mL of C. albicans SSY50-B strain was incubated at 37 °C for 24 h with AMPs ToAP2 (6.25 µM) and NDBP-5.7 (25 µM) as described previously. Then, 20 μL of each culture was deposited in a glass slide and incubated at 35 ± 2 °C for 20 min. The effect of the peptides on fungal cells was evaluated on a TT-AFM microscope from AFM Workshop (USA) in tapping mode (vibrating) using a silicon cantilever (AppNano, USA) with a resonance frequency of approximately 353 kHz. The images (6 µm x 6 µm, 512 lines) were analyzed using the Gwyddion 2.40 software.

Effect of AMPs on the C. albicans dimorphic transition

Filamentation assays using a suspension of C. albicans SC 5314 cells, in a final volume of 100 µL, were performed according to Yang22 and Derengowski96 with modifications. Briefly, in a 96-well polystyrene microplate, 1 × 104 cells/mL fungal cells were inoculated in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with L-glutamine and buffered to pH 7.0 with 165 mM MOPS, in the presence or absence of the peptides and cultivated at 37 °C. The cultures were photographed at different time points using an inverted microscope (Axio Observer Z1 Carl Zeiss Microscopy, USA). We took several pictures from each well of each experimental condition (at least 8) and a representative picture from each treatment was used for the figure. The number of cells showing germ-tubes and their average size were evaluated using the ImageJ 1.51 s software. The assay was performed in biological triplicates. Time-lapse microscopy was performed in the same microscope, with bright field images taken every 5 minutes for 24 h at 37 °C in the presence of at MIC and subMIC concentrations of ToAP2 (12.5 and 6.25 µM) and NDBP-5.7 (50 and 25 µM). The video was rendered in Blender 3D software at 15 fps.

Effect of the combination of AMPs and conventional antifungal on planktonic C. albicans

Both peptides, amphotericin B (Stock solution 250 μg/mL in deionized water from Sigma-Aldrich USA) and fluconazole (Sigma-Aldrich USA) stock solutions were diluted in sterile MilliQ water. For the assays the molecules were used in the following concentrations: ToAP2 (12.5–0.39 µM); NDBP-5.7 (25–0.78 µM); amphotericin B (1.08–0.03 µM); fluconazole (1.62–0.05 µM).

The combinatory effects between both AMPs and also between each of them and fluconazole or amphotericin B were tested using the checkerboard assay with some modifications41. Cells of C. albicans SC 5314 (2 × 103 cells/mL in 100 µL) were inoculated in RPMI 1640 in the presence of different concentrations of combined AMPs or AMPs plus antifungals. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. After that, cell viability was evaluated using alamarBlue (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 9% in a fluorescence plate reader with excitation at 550 nm and emission at 585 nm (SpectraMax M plate reader). This assay was performed in biological triplicates for each of the combinations tested. The synergistic action was evaluated by the Fractional Inhibitory Concentration (FIC).

We interpreted the FIC values obtained with the different drug combinations as synergistic (FIC ≤ 0.5), additive (0.5 < FIC ≤ 1.0), indifferent (1.0 < FIC ≤ 2.0) and antagonistic (FIC > 2.0)97.

Antifungal action of AMPs against C. albicans biofilms

The antifungal activity of the AMPs against C. albicans SC 5314 biofilms was assessed using a microplate alamarBlue susceptibility assay as previously described by Repp et al.98. Briefly, a 100 µL inoculum containing 1 × 106 cells/mL of C. albicans in RPMI 1640 medium was added to the wells of a 96-well polystyrene microplate and incubated at 37 °C for 4 h (early phase) or 24 h (mature biofilm). After that, biofilms were washed three times with PBS to remove non-adherent cells and each well received fresh medium with different concentrations of ToAP2 (100 to 3.12 μM for early phase and 200 to 6.25 μM for mature biofilms); NDBP-5.7 (200 to 6.25 μM for early phase and 400 to 12.5 μM for mature biofilms), amphotericin B (1.08 to 0.03 μM for both early-phase and mature biofilms) or fluconazole (104 to 3.25 μM for both early-phase and mature biofilms) and the plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Cell viability was evaluated using the alamarBlue reagent, in a concentration of 9%, and fluorescence was detected on a SpectraMax M plate reader (excitation at 550 nm and emission at 585 nm). Cell viability was also analyzed using the fluorescence dye Phloxine B (0.01%) and observing the cells in an inverted microscope (Axio Observer Z1 Carl Zeiss Microscopy, USA) (excitation: 546/12 nm; emission: 607/80 nm). All assays were done in biological triplicates.

Evaluation of cell membrane integrity of biofilm cells

Membrane permeabilization of C. albicans biofilm cells was evaluated using an adaptation of the rhodamine 6 G efflux assay as described by Szczepaniak42 One hundred microliters of a cell suspension of C. albicans SC 5314 containing 1 × 106 cells/mL was incubated at 37 °C in 96-well microplates for 4 or 24 h, in RPMI medium supplemented with MOPS. After the incubation times, the biofilms were washed three times with PBS and incubated for 2 h in PBS. Afterwards, all the wells received a solution of Rhodamine 6 G in PBS (10 µM) and were incubated for an additional 30 minutes. After this incubation, the biofilms were washed three times with PBS to remove the non-internalized dye, received different concentrations of ToAP2 or NDBP-5.7 diluted in PBS and were incubated for an additional 24 h. Untreated biofilms and biofilms treated with Amphotericin B (1.08 µM in PBS) and Fluconazole (52 µM in PBS) were used as controls. After 24 h, the supernatant was removed, and fluorescence measured in a fluorescence plate reader with excitation at 550 nm and emission at 585 nm (SpectraMax M plate reader). The test was carried out in biological triplicates.

Galleria mellonella infection

In vivo toxicity and efficacy against C. albicans infection of ToAP2 were tested using G. mellonella larvae weighting 250–300 mg as described before99. For the toxicity assay, groups of 16 randomly selected larvae were inoculated with different doses of ToAP2 (0, 40, 20 and 10 mg/kg) diluted in PBS in the last proleg using a Hamilton syringe and the larvae were incubated at 37 °C. Larva survival was evaluated daily for 7 days, and larva death was defined by the absence of movement in response to touch100. For protection assays, each larva received an inoculum of 5 × 105 C. albicans cells and was incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. After that, different doses of ToAP2 peptides diluted in PBS were injected into the infected larvae and the animals were incubated at 37 °C for 7 days. Amphotericin B (2 mg/kg) and PBS alone were used as controls. The assay was performed twice.

Histopathological analysis of G. mellonella

Histopathological evaluation was performed according to a standard protocol85. Three larvae from each group (non-infected, infected, infected + ToAP2 40 mg/Kg and infected + Amphotericin B 2 mg/Kg) were used after 24 h of incubation at 37 °C. The larvae were fixed with 10% buffered formalin for 24 h and then transverse and longitudinal incisions were made. The samples were dehydrated with increasing concentrations of ethanol, followed by xylol and incorporated with paraffin. Tissue sections (6 micron) were made with a microtome and placed on glass slides with 5% albumin. The slides were then stained with periodic acid Schiff (PAS) solution and observed in inverted microscope (Axio Observer Z1 Carl Zeiss Microscopy, USA).

Statistical analyzes

Except for the G. mellonella infection assay, which was performed as two biological replicates in different days with similar results, all other analyses were done in biological triplicates performed on different days. ANOVA and Tukey tests were used as post-tests, being considered statistically significant results when p ≤ 0.05. Long-rank was used in the analysis of Mantel-Cox survival curves.

References

Tsui, C., Kong, E. F. & Jabra-Rizk, M. A. Pathogenesis of Candida albicans biofilm. Pathogens and disease 74, ftw018, https://doi.org/10.1093/femspd/ftw018 (2016).

Tong, Y. & Tang, J. Candida albicans infection and intestinal immunity. Microbiological research 198, 27–35, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micres.2017.02.002 (2017).

Martins, N., Ferreira, I. C., Barros, L., Silva, S. & Henriques, M. Candidiasis: predisposing factors, prevention, diagnosis and alternative treatment. Mycopathologia 177, 223–240, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11046-014-9749-1 (2014).

Spampinato, C. & Leonardi, D. Candida infections, causes, targets, and resistance mechanisms: traditional and alternative antifungal agents. BioMed research international 2013, 204237, https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/204237 (2013).

Gulati, M. & Nobile, C. J. Candida albicans biofilms: development, regulation, and molecular mechanisms. Microbes and infection 18, 310–321, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micinf.2016.01.002 (2016).

Xu, K., Wang, J. L., Chu, M. P. & Jia, C. Activity of coumarin against Candida albicans biofilms. Journal de mycologie medicale 29, 28–34, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mycmed.2018.12.003 (2019).

Lee, W. J. et al. Factors and outcomes associated with candidemia caused by non-albicans Candida spp versus Candida albicans in children. American journal of infection control 46, 1387–1393, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajic.2018.05.015 (2018).

Gow, N. A., van de Veerdonk, F. L., Brown, A. J. & Netea, M. G. Candida albicans morphogenesis and host defence: discriminating invasion from colonization. Nature reviews. Microbiology 10, 112–122, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2711 (2011).

Calderone, R. A. & Fonzi, W. A. Virulence factors of Candida albicans. Trends in microbiology 9, 327–335, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0966-842x(01)02094-7 (2001).

Vieira de Melo, A. P. et al. Virulence factors of Candida spp. obtained from blood cultures of patients with candidemia attended at tertiary hospitals in Northeast Brazil. Journal de mycologie medicale 29, 132–139, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mycmed.2019.02.002 (2019).

Brunke, S., Mogavero, S., Kasper, L. & Hube, B. Virulence factors in fungal pathogens of man. Current opinion in microbiology 32, 89–95, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mib.2016.05.010 (2016).

Nobile, C. J. & Johnson, A. D. Candida albicans Biofilms and Human Disease. Annual review of microbiology 69, 71–92, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-micro-091014-104330 (2015).

Cleary, I. A. et al. Examination of the pathogenic potential of Candida albicans filamentous cells in an animal model of haematogenously disseminated candidiasis. FEMS yeast research 16, fow011, https://doi.org/10.1093/femsyr/fow011 (2016).

Moyes, D. L. et al. Candidalysin is a fungal peptide toxin critical for mucosal infection. Nature 532, 64–68, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature17625 (2016).

Vila, T. et al. Targeting Candida albicans filamentation for antifungal drug development. Virulence 8, 150–158, https://doi.org/10.1080/21505594.2016.1197444 (2017).

Hofs, S., Mogavero, S. & Hube, B. Interaction of Candida albicans with host cells: virulence factors, host defense, escape strategies, and the microbiota. Journal of microbiology 54, 149–169, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12275-016-5514-0 (2016).

Desai, J. V., Mitchell, A. P. & Andes, D. R. Fungal biofilms, drug resistance, and recurrent infection. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine 4, https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a019729 (2014).

Sari, S. et al. Discovery of new azoles with potent activity against Candida spp. and Candida albicans biofilms through virtual screening. European journal of medicinal chemistry 179, 634–648, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.06.083 (2019).

Lohse, M. B., Gulati, M., Johnson, A. D. & Nobile, C. J. Development and regulation of single- and multi-species Candida albicans biofilms. Nature reviews. Microbiology 16, 19–31, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro.2017.107 (2018).

Moraes, D. C. & Ferreira-Pereira, A. Insights on the anticandidal activity of non-antifungal drugs. Journal de mycologie medicale 29, 253–259, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mycmed.2019.07.004 (2019).

Gulshan, K. & Moye-Rowley, W. S. Multidrug resistance in fungi. Eukaryotic cell 6, 1933–1942, https://doi.org/10.1128/EC.00254-07 (2007).

Yang, L. F. et al. Dracorhodin perchlorate inhibits biofilm formation and virulence factors of Candida albicans. Journal de mycologie medicale 28, 36–44, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mycmed.2017.12.011 (2018).

El-Houssaini, H. H., Elnabawy, O. M., Nasser, H. A. & Elkhatib, W. F. Correlation between antifungal resistance and virulence factors in Candida albicans recovered from vaginal specimens. Microbial pathogenesis 128, 13–19, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2018.12.028 (2019).

Ng, S. M. S. et al. Structure-activity relationship studies of ultra-short peptides with potent activities against fluconazole-resistant Candida albicans. European journal of medicinal chemistry 150, 479–490, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.03.027 (2018).

Yeung, A. T., Gellatly, S. L. & Hancock, R. E. Multifunctional cationic host defence peptides and their clinical applications. Cellular and molecular life sciences: CMLS 68, 2161–2176, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00018-011-0710-x (2011).

Huang, Y., Huang, J. & Chen, Y. Alpha-helical cationic antimicrobial peptides: relationships of structure and function. Protein & cell 1, 143–152, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13238-010-0004-3 (2010).

Neelabh, Singh, K. & Rani, J. Sequential and Structural Aspects of Antifungal Peptides from Animals, Bacteria and Fungi Based on Bioinformatics Tools. Probiotics and antimicrobial proteins 8, 85–101, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12602-016-9212-3 (2016).

Falanga, A. et al. Marine Antimicrobial Peptides: Nature Provides Templates for the Design of Novel Compounds against Pathogenic Bacteria. International journal of molecular sciences 17, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms17050785 (2016).

Wiesner, J. & Vilcinskas, A. Antimicrobial peptides: the ancient arm of the human immune system. Virulence 1, 440–464, https://doi.org/10.4161/viru.1.5.12983 (2010).

Brown, K. L. & Hancock, R. E. Cationic host defense (antimicrobial) peptides. Current opinion in immunology 18, 24–30, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coi.2005.11.004 (2006).

Bondaryk, M., Staniszewska, M., Zielinska, P. & Urbanczyk-Lipkowska, Z. Natural Antimicrobial Peptides as Inspiration for Design of a New Generation Antifungal Compounds. Journal of fungi 3, https://doi.org/10.3390/jof3030046 (2017).

Mahlapuu, M., Hakansson, J., Ringstad, L. & Bjorn, C. Antimicrobial Peptides: An Emerging Category of Therapeutic Agents. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology 6, 194, https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2016.00194 (2016).

Nijnik, A. & Hancock, R. Host defence peptides: antimicrobial and immunomodulatory activity and potential applications for tackling antibiotic-resistant infections. Emerging health threats journal 2, e1, https://doi.org/10.3134/ehtj.09.001 (2009).

Tan, L. et al. Antifungal activity of spider venom-derived peptide lycosin-I against Candida tropicalis. Microbiological research 216, 120–128, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micres.2018.08.012 (2018).

Mirski, T., Niemcewicz, M., Bartoszcze, M., Gryko, R. & Michalski, A. Utilisation of peptides against microbial infections - a review. Annals of agricultural and environmental medicine: AAEM 25, 205–210, https://doi.org/10.26444/aaem/74471 (2017).

Almaaytah, A. & Albalas, Q. Scorpion venom peptides with no disulfide bridges: a review. Peptides 51, 35–45, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.peptides.2013.10.021 (2014).

Yasir, M., Willcox, M. D. P. & Dutta, D. Action of Antimicrobial Peptides against Bacterial Biofilms. Materials 11, https://doi.org/10.3390/ma11122468 (2018).

Guilhelmelli, F. et al. Activity of Scorpion Venom-Derived Antifungal Peptides against Planktonic Cells of Candida spp. and Cryptococcus neoformans and Candida albicans. Biofilms. Frontiers in microbiology 7, 1844, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.01844 (2016).

Zeng, X. C., Corzo, G. & Hahin, R. Scorpion venom peptides without disulfide bridges. IUBMB life 57, 13–21, https://doi.org/10.1080/15216540500058899 (2005).

Saville, S. P., Lazzell, A. L., Monteagudo, C. & Lopez-Ribot, J. L. Engineered control of cell morphology in vivo reveals distinct roles for yeast and filamentous forms of Candida albicans during infection. Eukaryotic cell 2, 1053–1060, https://doi.org/10.1128/ec.2.5.1053-1060.2003 (2003).

Guo, Q., Sun, S., Yu, J., Li, Y. & Cao, L. Synergistic activity of azoles with amiodarone against clinically resistant Candida albicans tested by chequerboard and time-kill methods. Journal of medical microbiology 57, 457–462, https://doi.org/10.1099/jmm.0.47651-0 (2008).

Szczepaniak, J., Cieslik, W., Romanowicz, A., Musiol, R. & Krasowska, A. Blocking and dislocation of Candida albicans Cdr1p transporter by styrylquinolines. International journal of antimicrobial agents 50, 171–176, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2017.01.044 (2017).

Ksiezopolska, E. & Gabaldon, T. Evolutionary Emergence of Drug Resistance in Candida Opportunistic Pathogens. Genes 9, https://doi.org/10.3390/genes9090461 (2018).

Ciumac, D., Gong, H., Hu, X. & Lu, J. R. Membrane targeting cationic antimicrobial peptides. Journal of colloid and interface science 537, 163–185, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcis.2018.10.103 (2019).

Lyu, Y., Yang, Y., Lyu, X., Dong, N. & Shan, A. Antimicrobial activity, improved cell selectivity and mode of action of short PMAP-36-derived peptides against bacteria and Candida. Scientific reports 6, 27258, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep27258 (2016).

Goncalves, S. et al. Psd1 Effects on Candida albicans Planktonic Cells and Biofilms. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology 7, 249, https://doi.org/10.3389/fcimb.2017.00249 (2017).

Durnas, B. et al. Candidacidal Activity of Selected Ceragenins and Human Cathelicidin LL-37 in Experimental Settings Mimicking Infection Sites. PloS one 11, e0157242, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0157242 (2016).

Polonelli, L. et al. A Naturally Occurring Antibody Fragment Neutralizes Infectivity of Diverse Infectious Agents. Scientific reports 6, 35018, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep35018 (2016).

Seyedjavadi, S. S. et al. The Antifungal Peptide MCh-AMP1 Derived From Matricaria chamomilla Inhibits Candida albicans Growth via Inducing ROS Generation and Altering Fungal Cell Membrane Permeability. Frontiers in microbiology 10, 3150, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.03150 (2019).

Wang, K. et al. Antimicrobial peptide protonectin disturbs the membrane integrity and induces ROS production in yeast cells. Biochimica et biophysica acta 1848, 2365–2373, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamem.2015.07.008 (2015).

Li, L. et al. Mechanism of antifungal activity of antimicrobial peptide APP, a cell-penetrating peptide derivative, against Candida albicans: intracellular DNA binding and cell cycle arrest. Applied microbiology and biotechnology 100, 3245–3253, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00253-015-7265-y (2016).

Choi, H., Hwang, J. S., Kim, H. & Lee, D. G. Antifungal effect of CopA3 monomer peptide via membrane-active mechanism and stability to proteolysis of enantiomeric D-CopA3. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 440, 94–98, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.09.021 (2013).

Bechinger, B. & Gorr, S. U. Antimicrobial Peptides: Mechanisms of Action and Resistance. Journal of dental research 96, 254–260, https://doi.org/10.1177/0022034516679973 (2017).

Raheem, N. & Straus, S. K. Mechanisms of Action for Antimicrobial Peptides With Antibacterial and Antibiofilm Functions. Frontiers in microbiology 10, 2866, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.02866 (2019).

Mayer, F. L. & Kronstad, J. W. Disarming Fungal Pathogens: Bacillus safensis Inhibits Virulence Factor Production and Biofilm Formation by Cryptococcus neoformans and Candida albicans. mBio 8, https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.01537-17 (2017).

Ogasawara, A. et al. Hyphal formation of Candida albicans is inhibited by salivary mucin. Biological & pharmaceutical bulletin 30, 284–286, https://doi.org/10.1248/bpb.30.284 (2007).

Theberge, S., Semlali, A., Alamri, A., Leung, K. P. & Rouabhia, M. C. albicans growth, transition, biofilm formation, and gene expression modulation by antimicrobial decapeptide KSL-W. BMC microbiology 13, 246, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2180-13-246 (2013).

Akerey, B., Le-Lay, C., Fliss, I., Subirade, M. & Rouabhia, M. In vitro efficacy of nisin Z against Candida albicans adhesion and transition following contact with normal human gingival cells. Journal of applied microbiology 107, 1298–1307, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2672.2009.04312.x (2009).

Sun, L., Liao, K. & Wang, D. Effects of magnolol and honokiol on adhesion, yeast-hyphal transition, and formation of biofilm by Candida albicans. PloS one 10, e0117695, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0117695 (2015).

Gorr, S. U., Flory, C. M. & Schumacher, R. J. In vivo activity and low toxicity of the second-generation antimicrobial peptide DGL13K. PloS one 14, e0216669, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216669 (2019).

Kodedova, M. & Sychrova, H. Synthetic antimicrobial peptides of the halictines family disturb the membrane integrity of Candida cells. Biochimica et biophysica acta. Biomembranes 1859, 1851–1858, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbamem.2017.06.005 (2017).

Harris, M. R. & Coote, P. J. Combination of caspofungin or anidulafungin with antimicrobial peptides results in potent synergistic killing of Candida albicans and Candida glabrata in vitro. International journal of antimicrobial agents 35, 347–356, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.11.021 (2010).

Lum, K. Y. et al. Activity of Novel Synthetic Peptides against Candida albicans. Scientific reports 5, 9657, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep09657 (2015).

MacCallum, D. M., Desbois, A. P. & Coote, P. J. Enhanced efficacy of synergistic combinations of antimicrobial peptides with caspofungin versus Candida albicans in insect and murine models of systemic infection. European journal of clinical microbiology & infectious diseases: official publication of the European Society of Clinical Microbiology 32, 1055–1062, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-013-1850-8 (2013).

Tavanti, A. et al. Fungicidal activity of the human peptide hepcidin 20 alone or in combination with other antifungals against Candida glabrata isolates. Peptides 32, 2484–2487, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.peptides.2011.10.012 (2011).

Vriens, K. et al. Synergistic Activity of the Plant Defensin HsAFP1 and Caspofungin against Candida albicans Biofilms and Planktonic Cultures. PloS one 10, e0132701, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0132701 (2015).

Wei, G. X. & Bobek, L. A. In vitro synergic antifungal effect of MUC7 12-mer with histatin-5 12-mer or miconazole. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy 53, 750–758, https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkh181 (2004).

Hale, J. D. & Hancock, R. E. Alternative mechanisms of action of cationic antimicrobial peptides on bacteria. Expert review of anti-infective therapy 5, 951–959, https://doi.org/10.1586/14787210.5.6.951 (2007).

Gray, K. C. et al. Amphotericin primarily kills yeast by simply binding ergosterol. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109, 2234–2239, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1117280109 (2012).

Mesa-Arango, A. C. et al. The production of reactive oxygen species is a universal action mechanism of Amphotericin B against pathogenic yeasts and contributes to the fungicidal effect of this drug. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy 58, 6627–6638, https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.03570-14 (2014).

Scorzoni, L. et al. Antifungal Therapy: New Advances in the Understanding and Treatment of Mycosis. Frontiers in microbiology 8, 36, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2017.00036 (2017).

Mathe, L. & Van Dijck, P. Recent insights into Candida albicans biofilm resistance mechanisms. Current genetics 59, 251–264, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00294-013-0400-3 (2013).

Troskie, A. M. et al. Synergistic activity of the tyrocidines, antimicrobial cyclodecapeptides from Bacillus aneurinolyticus, with amphotericin B and caspofungin against Candida albicans biofilms. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy 58, 3697–3707, https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.02381-14 (2014).

Olson, M. E., Ceri, H., Morck, D. W., Buret, A. G. & Read, R. R. Biofilm bacteria: formation and comparative susceptibility to antibiotics. Canadian journal of veterinary research = Revue canadienne de recherche veterinaire 66, 86–92 (2002).

Roscetto, E. et al. Antifungal and anti-biofilm activity of the first cryptic antimicrobial peptide from an archaeal protein against Candida spp. clinical isolates. Scientific reports 8, 17570, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-35530-0 (2018).

Uppuluri, P., Srinivasan, A., Ramasubramanian, A. & Lopez-Ribot, J. L. Effects of fluconazole, amphotericin B, and caspofungin on Candida albicans biofilms under conditions of flow and on biofilm dispersion. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy 55, 3591–3593, https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01701-10 (2011).

Mukherjee, P. K., Chandra, J., Kuhn, D. M. & Ghannoum, M. A. Mechanism of fluconazole resistance in Candida albicans biofilms: phase-specific role of efflux pumps and membrane sterols. Infection and immunity 71, 4333–4340, https://doi.org/10.1128/iai.71.8.4333-4340.2003 (2003).

Doke, S. K., Raut, J. S., Dhawale, S. & Karuppayil, S. M. Sensitization of Candida albicans biofilms to fluconazole by terpenoids of plant origin. The Journal of general and applied microbiology 60, 163–168 (2014).

Lee, J. H., Kim, Y. G., Gupta, V. K., Manoharan, R. K. & Lee, J. Suppression of Fluconazole Resistant Candida albicans Biofilm Formation and Filamentation by Methylindole Derivatives. Frontiers in microbiology 9, 2641, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.02641 (2018).

Bruzual, I., Riggle, P., Hadley, S. & Kumamoto, C. A. Biofilm formation by fluconazole-resistant Candida albicans strains is inhibited by fluconazole. The Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy 59, 441–450, https://doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkl521 (2007).

Panariello, B. H. D., Klein, M. I., Alves, F. & Pavarina, A. C. DNase increases the efficacy of antimicrobial photodynamic therapy on Candida albicans. biofilms. Photodiagnosis and photodynamic therapy 27, 124–131, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pdpdt.2019.05.038 (2019).

Nett, J., Lincoln, L., Marchillo, K. & Andes, D. Beta -1,3 glucan as a test for central venous catheter biofilm infection. The Journal of infectious diseases 195, 1705–1712, https://doi.org/10.1086/517522 (2007).

Nett, J. E., Crawford, K., Marchillo, K. & Andes, D. R. Role of Fks1p and matrix glucan in Candida albicans biofilm resistance to an echinocandin, pyrimidine, and polyene. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy 54, 3505–3508, https://doi.org/10.1128/AAC.00227-10 (2010).

Whiteway, M. & Bachewich, C. Morphogenesis in Candida albicans. Annual review of microbiology 61, 529–553, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093341 (2007).

Scorzoni, L. et al. Antifungal efficacy during Candida krusei infection in non-conventional models correlates with the yeast in vitro susceptibility profile. PloS one 8, e60047, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0060047 (2013).

Gong, Y. et al. Antifungal Activity and Potential Mechanism of N-Butylphthalide Alone and in Combination With Fluconazole Against Candida albicans. Frontiers in microbiology 10, 1461, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.01461 (2019).

Liu, X. et al. Synergistic Antifungal Effect of Fluconazole Combined with Licofelone against Resistant Candida albicans. Frontiers in microbiology 8, 2101, https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2017.02101 (2017).

Pappas, P. G., Lionakis, M. S., Arendrup, M. C., Ostrosky-Zeichner, L. & Kullberg, B. J. Invasive candidiasis. Nature reviews. Disease primers 4, 18026, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrdp.2018.26 (2018).

Bongomin, F., Gago, S., Oladele, R. O. & Denning, D. W. Global and Multi-National Prevalence of Fungal Diseases-Estimate Precision. Journal of fungi 3, https://doi.org/10.3390/jof3040057 (2017).

Berkow, E. L. & Lockhart, S. R. Fluconazole resistance in Candida species: a current perspective. Infection and drug resistance 10, 237–245, https://doi.org/10.2147/IDR.S118892 (2017).

Feng, W. et al. Research of Mrr1, Cap1 and MDR1 in Candida albicans resistant to azole medications. Experimental and therapeutic medicine 15, 1217–1224, https://doi.org/10.3892/etm.2017.5518 (2018).

Grossman, N. T., Chiller, T. M. & Lockhart, S. R. Epidemiology of echinocandin resistance in Candida. Current fungal infection reports 8, 243–248, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12281-014-0209-7 (2014).

Spettel, K. et al. Analysis of antifungal resistance genes in Candida albicans and Candida glabrata using next generation sequencing. PloS one 14, e0210397, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210397 (2019).

CLSI. Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute 3th ed. CLSI standard M27-A3. Wayne, PA: (2008).

Rodrigues de Araujo, A. et al. Antifungal and anti-inflammatory potential of eschweilenol C-rich fraction derived from Terminalia fagifolia Mart. Journal of ethnopharmacology 240, 111941, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2019.111941 (2019).

Derengowski, L. S. et al. Antimicrobial effect of farnesol, a Candida albicans quorum sensing molecule, on Paracoccidioides brasiliensis growth and morphogenesis. Annals of clinical microbiology and antimicrobials 8, 13, https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-0711-8-13 (2009).

Bonapace, C. R., Bosso, J. A., Friedrich, L. V. & White, R. L. Comparison of methods of interpretation of checkerboard synergy testing. Diagnostic microbiology and infectious disease 44, 363–366, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0732-8893(02)00473-x (2002).

Repp, K. K., Menor, S. A. & Pettit, R. K. Microplate Alamar blue assay for susceptibility testing of Candida albicans biofilms. Medical mycology 45, 603–607, https://doi.org/10.1080/13693780701581458 (2007).

Ignasiak, K. & Maxwell, A. Galleria mellonella (greater wax moth) larvae as a model for antibiotic susceptibility testing and acute toxicity trials. BMC research notes 10, 428, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-017-2757-8 (2017).

Mylonakis, E. et al. Galleria mellonella as a model system to study Cryptococcus neoformans pathogenesis. Infection and immunity 73, 3842–3850, https://doi.org/10.1128/IAI.73.7.3842-3850.2005 (2005).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. Stephen P. Saville and José L. Lopez-Ribot, for kindly provide the C. albicans strain SSY50-B. We thanks to Dr. Cynthia Kyaw and Dr. Hugo Costa Paes for helpful proofreading of final manuscript. We acknowledgments the support of the i3S Scientific Platform Histology and Electron Microscopy (HEMS), member of the PPBI (PPBI-POCI-01-0145-FEDER-022122). This research was supported by grants offered by National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) (CNPq 431958/2016-5) and the “Fundação de Apoio à Pesquisa do Distrito Federal (FAP-DF)/CNPq PRONEX grant (FAP-DF, 0193.001.200/2016). We are grateful to the Post-graduation Program in Molecular Pathology (FM/UnB) for support J.D and PH with a fellowship and also with partial publication fees payment.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.D. designed, performed all experiments and carried out the data analysis. C.S.-S., contributed to antimicrobial assays. J.D., J.L., P.E., A.A. and J.S. carry out peptide sequence, purity and stability evaluation, and also contributed to Atomic Force Microscopy experiments. PH contributed to membrane permeability analyzes. W.C. and M.G. performed histopathology tests. A.N. supervised Flow cytometry and microscopy analysis and contributed to the final revision of the manuscript. P.A. and I.S.-P. supervised all work and contributed in the writing and revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

do Nascimento Dias, J., de Souza Silva, C., de Araújo, A.R. et al. Mechanisms of action of antimicrobial peptides ToAP2 and NDBP-5.7 against Candida albicans planktonic and biofilm cells. Sci Rep 10, 10327 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-67041-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-67041-2

This article is cited by

-

Exploring the Therapeutic Potential of Scorpion-Derived Css54 Peptide Against Candida albicans

Journal of Microbiology (2024)

-

In Vitro and In Vivo Anti-Candida albicans Activity of a Scorpion-Derived Peptide

Probiotics and Antimicrobial Proteins (2024)

-

K-aurein: A notable aurein 1.2-derived peptide that modulates Candida albicans filamentation and reduces biofilm biomass

Amino Acids (2023)

-

Anticandidal Activity and Mechanism of Action of Several Cationic Chimeric Antimicrobial Peptides

International Journal of Peptide Research and Therapeutics (2023)

-

Streptomyces: Derived Active Extract Inhibits Candida albicans Biofilm Formation

Current Microbiology (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.