Abstract

The glass sponge Aphrocallistes vastus contributes to the formation of large reefs unique to the Northeast Pacific Ocean. These habitats have tremendous filtration capacity that facilitates flow of carbon between trophic levels. Their sensitivity and resilience to climate change, and thus persistence in the Anthropocene, is unknown. Here we show that ocean acidification and warming, alone and in combination have significant adverse effects on pumping capacity, contribute to irreversible tissue withdrawal, and weaken skeletal strength and stiffness of A. vastus. Within one month sponges exposed to warming (including combined treatment) ceased pumping (50–60%) and exhibited tissue withdrawal (10–25%). Thermal and acidification stress significantly reduced skeletal stiffness, and warming weakened it, potentially curtailing reef formation. Environmental data suggests conditions causing irreversible damage are possible in the field at +0.5 °C above current conditions, indicating that ongoing climate change is a serious and immediate threat to A. vastus, reef dependent communities, and potentially other glass sponges.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sponges have an important functional role in ecosystems worldwide and over the entire marine bathymetric gradient where they efficiently filter water, link food webs, and facilitate the flow of carbon between trophic levels1,2,3, alter the water column and its processes4,5, and provide biogenic habitat6. This is particularly true for the glass sponge Aphrocallistes vastus (class Hexactinellida), which – along with Heterochone calyx and Farrea occa – form large biogenic reefs that cover several square kilometres of the seafloor off the west coast of Canada7,8. These reefs are built through larval sponges settling atop the fused dead skeletons of previous generations, and therefore mechanical integrity of the sponge skeleton is vital to reef formation, persistence, and growth. While hexactinellids are widely distributed in the deep sea (>70 m)9, in British Columbia (BC), Canada, they occur as shallow as 20 m and form complex reefs, which are home to a rich community of fish and invertebrate species6,10. These reefs process considerable volumes of water (465–47,300 L/m2 per day), twice as fast as the next most intense suspension feeding community in the ocean (i.e. mussel beds), which could have strong impacts on local and regional bentho-pelagic coupling, nutrient cycling, and carbon sequestration6,11. These globally unique glass reefs, prior to their discovery in 1986, were thought to have been extinct for 40 million years7.

Although glass sponge reefs are now subject to ongoing intensive conservation efforts, responses of these and other sponge-dominated communities to ongoing environmental change remain largely unknown. Acidification could be detrimental to invertebrates, such as sponges, because of their inability to compensate for reductions in extracellular pH12, but responses of non-reef-building marine sponges to acidification in the lab and field are idiosyncratic and highly variable13,14,15,16,17,18. Also, no simple and consistent relationships have been found between temperature and pumping rate of ciliary suspension feeders19. Drastically different and species-specific responses to ocean acidification and warming make it difficult to predict the vulnerabilities of sponge species that have not been examined, like glass sponges. However, siliceous sponges, including hexactinellids, have survived pre-historical mass extinction events caused by ocean acidification20,21. Their prevalence at natural volcanic CO2 seeps in Papua New Guinea22, and persistence through rapid regional climate-induced warming along the Antarctic Peninsula23, suggests that siliceous sponges may do well under conditions of acidification and warming.

Here, we conducted a four-month mesocosm experiment to assess the effects of elevated temperature, CO2-induced acidification, and their interaction on pumping capacity, tissue withdrawal, and mechanical integrity of the skeletal structure of the reef-building glass sponge A. vastus. For this study, 32 juvenile specimens were randomly assigned to one of 16 aquaria (n = 2 per aquarium) set to one of four treatment combinations (4 aquaria per treatment combination): (1) control (ambient temperature = 8.6 C and pH = 7.8), (2) reduced pH (present-day temperature and projected year 2100 pH = 7.6; OA), (3) elevated temperature (projected year 2100 temperatures 10.4 C ( + 1.8 °C) and present-day pH = 7.8; OW) and (4) elevated temperature and reduced pH (projected year 2100 temperatures and pH; OAW). Fluorescent dye (Calcein) was injected near the sponge’s midsection to measure two aspects of pumping capacity: the time it took the dye to be expelled from the osculum (hereafter ‘minimum residence time’), and the vigor of the dye plume expelled from the oscula (‘pumping strength’ hereafter). Pumping strength was scored over a gradient of 0–6: ‘weak’ = a diffuse plume of dye (score 1–3), and ‘strong’ = dense plume of dye (4–6), ‘none’ = apparent pumping arrest (scored 0). ‘Apparent pumping arrest’ does not correspond to pumping arrest because a flowmeter was not used to record this, it does however infer that pumping was so weak that it was not observed with the use of a dye. Apparent pumping arrest is a common behavioral response to exposure to a stressor such as sediment24,25. Onset of tissue withdrawal was noted when it occurred. To assess sponge skeleton mechanical properties, we measured sponge skeleton fracture force (breaking point) and modulus (stiffness) at the end of the experiment.

Apparent pumping arrest

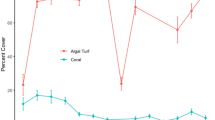

A greater proportion of sponges exposed to warming and/or acidification treatments ceased pumping than the control sponges over the course of the experiment (Fig. 1a), but there was no significant effect of acidification, warming, or their interaction on apparent pumping arrest over time (Table 1a). The onset of apparent pumping arrest was seen as early as two weeks in sponges exposed to warming (including OW and OAW), and the proportion of individuals not filtering remained relatively stable in the OA and OW treatments, but there were fluctuations observed in the OAW treatment combination (Fig. 1a).

Apparent pumping arrest (a), minimum residence time (b), pumping strength (c), and onset of tissue withdrawal (d) in the reef-building glass sponge Aphrocallistes vastus exposed to four treatment combinations. Treatment combinations include: ambient conditions (‘Control’), CO2-induced acidification (‘OA’), increased seawater temperature (‘OW’), and a combination of both (‘OAW’) for four months. (a) Colour gradient represents total apparent pumping arrest (dark shade) to strong pumping (light shade). (b) ‘Minimum residence time’ refers to time (in seconds) taken to expel dye from the oscula after being injected with a fixed volume, mean values exclude individuals that were not pumping (assigned a pumping strength score of zero). (c) ‘Pumping strength’ is comprised of a score assigned to the volume of the plume expelled from the oscula, mean values include individuals that were not pumping (score of zero). (d) “Kaplan-Meier survival curve” for the probability of observing tissue withdrawal in each individual. 95% confidence limits are shown (in d) and error bars represent standard error (SE; in b, c) of the mean (n = 8 per treatment combination).

Pumping capacity

Minimum residence times were similar across treatments early in the experiment, but then diverged through time in response to acidification and warming (Fig. 1b). Although minimum residence time remained constant in control tanks, it declined by 2- to 3.5- fold in sponges exposed to OA, OAW, OW treatment combinations. Individuals subjected to acidification and warming separately pumped the dye significantly slower than the control after four months (120 days) of exposure to these treatments (Table 1b). Treatment interaction dampened this negative response but not significantly.

After four months of exposure, sponges in OA, OAW, and OW tanks showed reduced pumping strength, by 2- to 5.5- fold compared to the control (Fig. 1c). Strength was significantly weaker in individuals subjected to acidification and warming relative to the control (Table 1c; Fig. 1c). Warmed sponges (OW and OAW) had depressed pumping strength as early as the first sampling point, whereas sponges in the acidification only treatment lost pumping strength more gradually (more details Supplementary Table S1). Notably, after three months, sponges exposed to elevated temperature alone showed increase in minimum residence time (slowed pumping) and decrease in pumping strength, but the pumping capacity of individuals in the OAW treatment (exposed to both acidification and warming) was relatively faster and stronger, similar to the acidified treatment. However, in the final (fourth) month pumping capacity of sponges in OAW ultimately worsened, mirroring that of individuals subjected to warming (Fig. 1). These patterns resulted in a significant Acidification x Warming x Time interaction (Table 1c).

Tissue withdrawal

The effects of acidification and warming on tissue withdrawal were large in magnitude, but significance was not detected (Table 1d), potentially as a result of the relatively low sample size (n = 8 per treatment combination). Yet, trends are alarming and worth detailing: individuals subjected to warming (including OW and OAW treatment combinations) had earlier onset (by one month) of tissue withdrawal relative to the control and OA treatment combinations. By the end of the experiment all (100%) sponges in the OA and >75% of sponges in the warmer (OW and OAW) treatment combinations had signs of tissue withdrawal, a 35–60% increase compared to control sponges (Fig. 1d). The Cox proportional hazards regression model estimated hazard ratio (Exp. Coeff. in Table 1d) suggests a threefold increase in the probability of acidified and warmed sponges showing signs of tissue withdrawal compared to those in the control.

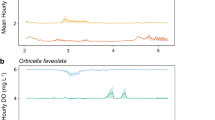

Skeletal breaking force per volume and stiffness

Experimental treatment combinations (OA, OW, OAW) reduced the force per volume required to break A. vastus skeleton (Fig. 2a), but only a significant effect of warming was detected (Table 1e). Both acidification and warming significantly reduced skeleton modulus (stiffness; Fig. 2b), meaning the skeleton became more elastic after four months exposure to these conditions (Table 1f). There were no significant Acidification x Warming interaction effects for these material properties.

Max breaking force per volume (N/mm3; a) and mean modulus (stiffness; MPa; b) withstood by fresh juvenile Aphrocallistes vastus skeleton. Skeleton samples were tested at the end of the experiment after four months exposure to four treatment combinations: ambient conditions (‘Control’), CO2-induced acidification (‘OA’), increased seawater temperature (‘OW’), and a combination of both (‘OAW’). Error bars represent standard error (SE) of the mean (n = 8 sponges per treatment combination, with 5 measurements per sponge).

Warming and acidification pose an immediate threat to sponge filtration and reef formation

Our results indicate that future acidification, warming, and their combination may have substantial adverse effects on the pumping capacity, tissue withdrawal, and structural integrity of the glass sponge A. vastus, a species that contributes to the formation of historically and ecologically important habitats unique to the Pacific Northwest.

Most worryingly, the onset of apparent pumping arrest was quick (occurring within two weeks) for sponges exposed to elevated temperatures regardless of acidification. Subsequent degradation was observed two weeks following apparent arrest. The rigid skeleton of glass sponges, like A. vastus, does not permit these animals to contract like other sponges from class Demospongiae (which possess both protein and silica spicules) in response to, for example, particle obstruction24,25. To protect themselves from this, glass sponges typically go into temporary apparent pumping arrest whereby they cease filtering particles from surrounding water to prevent particle obstruction24. It is possible that treatments caused significant stress, manifested as apparent pumping arrest leading to tissue withdrawal, throughout the experiment.

Warming can influence sponge-feeding behavior by reducing choanocyte chamber density, size, and therefore filtration efficiency26. Few glass sponges have successfully been kept in recirculating seawater, but for those that did survive for weeks to months, unusual changes in the structure of choanocyte chambers were noted over time27, which may help explain tissue withdrawal observed in control sponges. To the best of our knowledge there have been no studies investigating the effects of acidification and warming on glass sponge filtration, but there are some examples among demosponges. Similar to our findings for A. vastus, Rhopaloeides odorabile shows drastic reductions in pumping rates and feeding efficiency in response to warming13. In contrast, Dysidea avara filtration rates remain unaffected by natural changes in temperature28, but in Halichondria panicea rates increased at higher temperatures19. Overall, available data suggest that ocean warming impacts on filtration capacity could be species-specific, and the effects of warming will depend on whether a particular species is already near or above its thermal optimum.

The action potential controlling filtration in glass sponge Rhabdocalyptus dawsoni, is known to function within a narrow temperature range (7–12 °C)29, but it is unclear if this is the case for other glass sponges. Below 7 °C, sponges are unable to resume filtration after arrest, and cannot undergo arrest at temperatures above 12 °C, thereby making them more susceptible to starvation and clogging from sediments25. The ambient and upper limit of the temperatures examined in the present study were within the physiological tolerance limits of glass sponges, but signs of distress were still observed under the climatically realistic magnitude of warming used in our experiment. It is possible that prolonged exposure (>2 weeks, as defined by our study) to warming might further restrict the physiological limits of glass sponges and could cause a decrease in biomass of A. vastus populations as a result of starvation (marked by apparent pumping arrest).

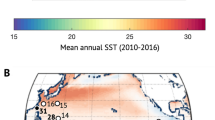

Periods of prolonged warming have already been observed in the field, at the collection site of the present study (Fig. 3) and in other Howe Sound bioherms30. Warm periods, defined as temperatures reaching >10.4 C with no more than 12 hrs of cooling (temperatures < 10.4 C), lasting 6–13 days occurred six times between July and October, 2016, with five brief periods of cooling in between warm periods, which corresponded to a weak temperature anomaly (La Niña year)31. Results suggest that irreversible tissue withdrawal could take place in A. vastus after 30 days of exposure to warming (>10.4 C), which could have occurred if it were not for several brief periods of cooling observed in the summer of 2016. Warming trends pose an immediate stress to glass sponge reefs, as the addition of 0.5 °C to the 2016 pattern would result in 140 consecutive days of warming, a period longer in length and warmer than the sponges were exposed to in the present study.

Daily average, maxima, and minima of one year (January 2016 – December 2016) iButton temperature logger data captured at the collection site, Field of a Thousand, off west Bowen Island. Dashed line represents the maximum temperature sponges experienced in the present study (10.4 °C). The recording iButton temperature logger was positioned at 23 m. (Data courtesy of Ocean Wise Research Institute).

Responses of glass sponges to ocean acidification have not previously been investigated; responses of species in other sponge classes are not well known and, similar to responses to warming, appear to be species-specific. Some species appear to be resistant to acidification: elevated temperatures caused significant adverse effects on abundant tropical sponge species, but acidification alone had little effect32. Cliona orientalis, a demosponge, had increased bioerosion rates under acidified conditions14; demosponge species were present near Mediterranean CO2 vent sites with pH values as low as 6.6 units16; no effect of acidification was found on the survival rates of Crella incrustans18; and Mycale grandis showed extraordinary resistance to acidification17. In contrast, increased mortality in response to acidification was seen in sponges Cliona celata15 and Tethya bergquistae18. Our study suggests glass sponges are less sensitive to ocean acidification than warming, at least within the range of change expected for these variables in the coming decades, but are not resilient to long-term exposure to either since both elevated temperature and acidification ultimately had detrimental outcomes for the sponges.

Importantly, the interactive effect of acidification and warming had mitigating effects on the pumping capacity of individuals exposed to warming for the first three months, mirroring the response of acidified sponges. The oscillations in pumping capacity and apparent arrest throughout the experiment suggest that the interactive effect of acidification may cause the sponges to intermittently start/stop pumping. Contrary to our work, the interaction between acidification and warming exacerbated the effect of temperature stress in heterotrophic sponge species32. However, acidification may mitigate these stresses in phototrophic species, reducing mortality, necrosis and bleaching of tropical sponges32,33. In the final month of our experiment, individuals subjected to a combination of elevated CO2 with warmer temperatures performed similarly to the temperature treatment suggesting that acidification may have a threshold and short-term buffering capacity. Because acidification did not dampen the presence of tissue withdrawal, it may not be able to mediate the effect of temperature and ultimate loss of this species in the long term.

It must be noted that there have been documented mass mortality of glass sponges (including A. vastus) in Howe Sound, where the sponges were collected for this study and several glass sponge reefs exist. These extensive glass sponge mortalities (including A. vastus) correlate with elevated temperatures reported during the 2009/2010 and 2015/2016 El Niño events30,34, and provide some indication that these sponges are sensitive to elevated temperatures. However, this period of warming was not associated with a decrease in pH35. Furthermore, acidification independent of warming has been documented in Howe Sound, but not associated with sponge mortalities35. From these field observations there can be no conclusions drawn regarding how temperature and acidification may interact in the field and how acidification may impact the sponges under natural circumstances. However, the patterns do qualitatively match the results seen in our experiment suggesting warming is the primary threat to glass sponges.

The combination of reduced skeletal stiffness (under warming and acidification) and strength (from warming) would be expected to slow or completely curtail reef formation. The fused and three-dimensional skeletal network, comprised of biosilica and chitin, held together at the joints with low concentrations of calcite, is responsible for the sponges’ rigid body that prevents disaggregation of the skeleton long after its death, allowing for reef development36,37,38,39. The dictyonine skeleton (fused robust scaffolding) is thought to reduce skeletal stiffness in glass sponges like A. vastus, providing natural flexibility to minimize stresses posed by hydrodynamic forces in shallower waters40. Material stiffness values (measured as Young’s modulus) from previous work on A. vastus are slightly higher (2.76–10.04 MPa)40 than those obtained in the present study (control sponges = 1.2 + 0.7 MPa). Discrepancies might be due to life stage differences as the present study was conducted on juvenile sponges (3–8 cm in height). Regardless, warmed and/or acidified sponges were half as stiff as the control sponges. Alterations to the skeleton, especially in terms of reduced stiffness (increased flexibility) as presented here, could reduce feeding efficiency, lowering the sponges’ critical water flow threshold, and potentially their distribution, restricting them to waters with higher food availability. Furthermore, under warming conditions the more brittle (measured as reduced force per volume) skeletons might collapse under the increasing weight of a growing sponge, which can reach 2–3 m in height36, and/or might not be able to withstand the myriad animals walking and swimming in and among the sponges40,41. Because we only examined material properties in living tissue, it is unclear how the dead skeleton would be altered by climate change and whether it too would succumb to the fate of the living skeleton, but it is reasonable to suspect that differences in skeletal strength apparent during life would perpetuate after death. This is critical as dead sponges are important for reef growth as larval glass sponges and other invertebrates settle and grow on the macerated skeleton36. The unique architecture of glass sponges vital to reef formation may be vulnerable to climate change.

Implications for associated biodiversity and ecosystem function

Exposure to acidification and warming reduced the feeding efficiency (i.e. increased minimum residence time and decreased pumping strength) of glass sponges, suggesting that the feeding ability of juvenile A. vastus might be diminished (2–5.5 fold) by the end of the century as a result of climate change. Cascading effects of impaired pumping on local and regional biogeochemical processes remain unknown, but are likely to be negative. Via their remarkable filtration capacity, sponges convert large quantities of suspended particles and dissolved organic carbon (DOC) into food for other animals1. Through feeding, excretion, and symbiont microbial activity, sponges are known to chemically transform seawater passing through their structure42. The 19 documented glass sponge reefs in the Salish Sea, for example, collectively filter 1.04 × 1011L of water each day, representing 1% of the total water volume in the Strait of Georgia and Howe Sound combined6. By doing so, glass sponges bring microbial food energy from marine and terrestrial sources into local food webs by feeding on and removing up to 90% of bacteria from the water11,43. Reduction in this tremendous filtration capacity, as well as the reefs’ eventual physical decimation, could alter local and regional microbial loop and energy supplied to the benthic community. Examples of breakdowns in bentho-pelagic coupling exist: sponge populations in Florida Bay have historically controlled phytoplankton blooms via particle removal and pumping rates44. Devastation of the sponge population in the area lead to increased toxic blooms in Florida Bay. Reduced skeletal strength could act as a positive feedback loop further weakening the sponge infrastructure and making it more prone to damage from inhabitants (fish and invertebrates) moving about the reef. Habitat loss as a consequence of ocean acidification45 and warming46 has negative downstream effects on biodiversity in coral reefs, mussel beds, and some macroalgal habitats. Similarly, we anticipate biodiversity loss in these ancient glass sponge habitats as a result of climate change.

Methods

Collection and husbandry

Juvenile A. vastus, ranging in height from 3 to 8 cm, were randomly selected from ‘Field of A Thousand’ dive site on the west side of Bowen Island (49.396, −123.397) in Howe Sound, British Columbia, Canada, under collection license XR 321 2017. Sponges were placed in plastic bags with ambient seawater (collected at depth) and stored in coolers for transportation to the laboratory at the University of British Columbia. To ensure longevity, sponges were slow drip acclimatized to their tank chemistry over the course of one hour by adding 100 mL of water to the collection bag (stored in a cooler) every 10 min from the respective tank in which an individual sponge was to be housed.

Two sponges were placed in each of sixteen 250 L recirculating seawater aquaria bubbled constantly with ambient air and equipped with a multistage filtration system, including biological filter (sock filtration, protein skimmer, and bioballs) and UV sterilizer. The source seawater was obtained locally from 16 m depth in Burrard Inlet, BC, and coarse filtered by the Vancouver Aquarium. Sponges were held in total darkness with red light exposure during feeding. White light exposure was kept to a minimum, 1 hr per month or less, to measure pumping activity and observe tissue withdrawal.

Ammonia, nitrite, and nitrate (using API Marine Master Test Kit) were monitored throughout the experiment. Twenty percent water changes were performed when necessary. Water changes were also conducted at least once per month during cleaning, which was kept at a minimum to avoid stressing the animals with excessive water movement. Siliconoxide was monitored with Salifert Si Profile Test kit. To supplement silica content in the water, two drops Sponge Excel Marine High-purity Silica from Brightwell Aquatics were added twice to each tank throughout the experiment.

The sponges were fed twice daily at fixed times (every 12 hrs) to approximate their natural exposure to tidal rhythm. Each sponge tank received: in the morning, 0.5 mL Reef Nutrition Roti Feast + 0.5 mL Reef Nutrition Oyster Feast/tank mixed with 10 mL seawater, fed to the sponges using Kent Marine Sea Squirt feeder; in the evening, two drops of concentrated Sponge Power (Korallen-Zucht Sponge Power) directly added to each tank. In addition, four times weekly, 0.5 mL Fauna Marine Ultra Min S and 0.5 mL Fauna Marine Ultra Min D mixed with 10 mL seawater was added to each tank using Kent Marine Sea Squirt feeder. All food was injected near the water’s surface to prevent contact or movement near the animal.

Experimental setup and water chemistry

The sponges were acclimated in their assigned tanks at 8–9 C for five days without food; on the sixth day, the sponges were fed and tanks were set to their experimental temperature and pH over 8 hrs. Experimental treatments were chosen based on conservative future projections (temperature + 1.8 °C and ΔpH –0.2 units based on year 2100 projections)47. The 16 experimental aquaria were divided equally into four treatments: (1) control (ambient temperature = 8.6 C and pH = 7.8), (2) reduced pH (present-day temperature and projected year 2100 and pH = 7.6), (3) elevated temperature (projected year 2100 temperatures 10.4 C ( + 1.8 °C) and present-day pH = 7.8) and (4) elevated temperature and reduced pH (projected year 2100 temperatures and pH). Because of a leak in the CO2 canister, acidification took place one week later than other treatments, but for conservative purposes its time span was treated similarly to other treatments for analyses.

Temperature was maintained using individual chillers connected to each tank. Elevated CO2 concentrations were achieved using mass flow controllers to bubble an appropriate mixture of compressed CO2 (100% CO2; Praxair) and ambient air (drawn from outside the building) from an air compressor. Control tanks were bubbled with ambient compressed air. Temperature was measured 5x per week using a combination of YSI (YSI Pro 30) and mercury thermometer. Seawater pH was measured 3–4x per week using Oakton pH 450 (two-point calibration with saltwater buffers AMP and TRIS, pH 6.77 and 8.09 respectively at 25 C). YSI was also used to monitor salinity.

Water samples for carbonate system parameters were collected bimonthly and stored with 10 μL Mercuric Chloride 5% (w/v) Aqueous for future analysis. Dissolved inorganic Carbon (DIC) was measured using DIC Analyzer Model AS-C3 Apollo Sci Tech, according to guidelines of the Standard Operating Procedure 248. Three replicates of 0.75 mL were taken for each sample. Results were normalized to a Certified Reference Material (CRM Batch No. 154) supplied by Prof. Andrew Dickson (Scripps Institution of Oceanography). Full carbonate system parameters were conducted on the control and acidified treatments using CO2SYS49 (Table 2).

Sponge pumping and tissue withdrawal

Pumping was monitored on days 16, 31, 50, 71, 92, and 120 from the start of the experiment. Two milliliters of freshly made fluorescent Calcein dye (4 g/L; Syndel Laboratories Ltd), a fluorescent derivative of fluorescein, was injected with a pipette positioned 0.5 cm from the sponge wall and halfway down the sponge’s structure to measure pumping capacity, which was quantified by calculating the time it took the dye to be expelled from the oscula (referred to as ‘minimum residence time’ hereafter), and scoring the density of the plume expelled from the oscula (‘pumping strength’ hereafter). We calculated minimum residence time as the amount of time in between dye injection and the emergence of the dye from the sponge osculum. Here, the time it took for the dye to be expelled from a set distance was calculated not by noting the time the dye appeared above the oscula (like in the dye front method50) but rather when it appeared at the edge of it (distance = 0 mm from oscula) therefore a flow rate could not be calculated. We consider minimum residence time a proxy measurement for pumping rate as we were unable to calculate pumping rate directly in such small specimens. In preliminary trials we observed that sponges with similar minimum resident times differed significantly in the shape of the exhalent dye plume (see examples in Supplementary Videos S1). Consequently, we added a measurement we refer to as “pumping strength”. Video of the sponges pumping were recorded with Sony Handycam so as to precisely measure the minimum residence time. Average minimum residence time for each treatment did not include those sponges that were not pumping. Pumping strength was scored over a gradient of 0–6: ‘weak’ = a diffuse (score 1–3) and ‘strong’ = dense (4–6) plume of dye, and ‘none’ = apparent pumping arrest (scored 0). The term ‘Apparent pumping arrest’ does not correspond to pumping arrest because a flowmeter was not used to record this, it does however infer that pumping was so weak that it was not observed with the use of a dye. Scores were determined by an unbiased observer. The quantity of dye expelled, speed at which this dye was ejected, and continuous versus puffs of dye were all factors considered when scoring a plume. The presence/absence of tissue withdrawal was monitored daily until first signs of tissue withdrawal appeared. Withdrawn tissue was easily distinguished from healthy tissue by its translucent (colourless) nature whereas healthy tissue maintained its original beige or orange colour (Fig. 4). After onset, tissue withdrawal was monitored every two weeks, for the remainder of the experiment.

All sponges survived through to the end of the experiment, except one sponge in the control treatment that died in the last month of the experiment. The final time point of this sponge was excluded from the analyses because its death was deemed to be caused by a microbial infection since the sponge died suddenly (within 24 hrs) despite pumping strongly and with no signs of tissue withdrawal, and developed strings of mucus in that 24 hrs period.

Mechanical properties

Skeleton breaking force per volume and modulus (stiffness) was tested using a standard compression method in a computer-interface tensometer (model 5500 R, Instron Corp., Canton, MA, USA). Skeleton was selected halfway down the sponge and cut into square pieces (approx. 1 cm2). These were placed in the cross-beam of the instrument and a maximum force of 4 N was gradually applied (load rate = 0.25 N/min; strain rate = 0.35 mm/s) to the skeleton until point of failure. Breaking force was recorded. Because thickness differed by sponge (1.7–4.6 mm), measurements of sponge skeletal thickness and cross-sectional area were used to standardize breaking force per volume. The compression surface consisted of a 3 mm diameter puncture probe. Modulus was calculated by dividing material stress with strain (i.e. the slope of the stress-strain curve produced during the compressive test). The average of 3–5 replicates was taken for analysis.

Statistical analyses

All statistical analyses were performed in R version 3.6.051 for Mac OS X. For all tests, significance was determined at p < 0.05. Data were transformed when necessary (as outlined below) to meet the assumptions of normality and equal variance. All mixed models were performed with package ‘nlme’52. Visual inspection of standard model validation graphs was used to verify model assumptions: residuals versus fitted values were used to verify homogeneity; a histogram or Quantile–Quantile (q–q) plot of the residuals for normality; and residuals versus each explanatory variable to check independence. Fixed and random predictor variables lacking explanatory power were eliminated via AIC model selection53. Optimal model structures were obtained first for random effects and next for fixed effects. To account for repeated measures (on individuals) through time, an autoregressive (AR1) correlation structure was included in the model during the selection process. In all cases, the most parsimonious model was selected (i.e., the one without interactions and/or fewer terms, least complex random structure, and removal of correlation structure where necessary).

Generalized linear mixed models (GLMM) were used to analyse apparent pumping arrest (GLMM, binomial distribution) and pumping strength (GLMM, Poisson distribution). The best model included a random intercept in which variation around that intercept depended on the sponge (nested within tank). Linear models (LM) were used on log-transformed minimum residence time, breaking force per volume, and modulus datasets. A “Kaplan-Meier survival curve” was generated using two pieces of data: status of final observation and time to event (here, first sighting of tissue withdrawal). A Cox proportional hazards regression model was used to test for the effects of acidification, warming, and their interaction on the probability of observing onset of withdrawn tissue through time, using package ‘survival’54,55. The Cox proportional hazard assumption was tested using Schoenfeld residuals with the function cox.zph. Sponges that did not show signs of tissue withdrawal were censored (considered to not have reached tissue withdrawal).

References

Bell, J. J. Functional roles of marine sponges. Estuar. Coast Shelf Sci. 79, 341–353 (2008).

De Goeij, J. M., Van Den Berg, H., Van Oostveen, M. M., Epping, E. H. & Van Duyl, F. C. Major bulk dissolved organic carbon (DOC) removal by encrusting coral reef cavity sponges. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 357, 139 (2008).

McMurray, S. E., Johnson, Z. I., Hunt, D. E., Pawlik, J. R. & Finelli, C. M. Selective feeding by the giant barrel sponge enhances foraging efficiency. Limnol. Oceanogr. 61(4), 1271–1286 (2016).

Diaz, M. C. & Rützler, K. Sponges: an essential component of Caribbean coral reefs. Bull. Mar. Sci. 69, 535–546 (2001).

Archer, S. K., Stevens, J. L., Rossi, R. E., Matterson, K. O. & Layman, C. A. Abiotic conditions drive significant variability in nutrient processing by a common Caribbean sponge, Ircinia felix. Limnol. Oceanogr. 62, 1783–1793 (2017).

Dunham, A. et al. Assessing condition and ecological role of deep-water biogenic habitats: Glass sponge reefs in the Salish Sea. Mar. Environ. Res. 141, 88–99 (2018).

Conway, K. W., Barrie, J. V., Austin, W. C. & Luternauer, J. L. Holocene sponge bioherms on the western Canadian continental shelf. Cont. Shelf. Res. 11(8–10), 771–90 (1991).

Krautter, M., Conway, K. W., Barrie, J. V. & Neuweiler, M. Discovery of a “living dinosaur”: globally unique modern hexactinellid sponge reefs off British Columbia, Canada. Facies 44, 265–82 (2001).

Van Soest, R. W. M. et al. Global Diversity of Sponges (Porifera). PLoS ONE 7, e35105 (2012).

Chu, J. W. F., Maldonado, M., Yahel, G. & Leys, S. P. Glass sponge reefs as a silicon sink. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 441, 1–14 (2011).

Kahn, A. S., Yahel, G., Chu, J. W. F., Tunnicliffe, V. & Leys, S. P. Benthic grazing and carbon sequestration by deep-water glass sponge reefs. Limnol. Oceanogr. 60(1), 78–88 (2015).

Pörtner, H. O. Ecosystem effects of ocean acidification in times of ocean warming: a physiologists view. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 373, 203–217 (2008).

Massaro, A. J. Selective filtration in the tropical marine sponge Rhopaloeides odorabile: impacts of elevated seawater temperature on feeding behavior. Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection 774 (2009).

Wisshak, M., Schönberg, C. H., Form, A. & Freiwald, A. Ocean acidification accelerates reef bioerosion. PLoS One 7(9), e45124 (2012).

Duckworth, A. R. & Peterson, B. J. Effects of seawater temperature and pH on the boring rates of the sponge Cliona celata in scallop shells. Mar. Biol. 160, 27–35 (2013).

Goodwin, C., Rodolfo Metalpa, R., Picton, B. & Hall-Spencer, J. M. Effects of ocean acidification on sponge communities. Mar Ecol. 35, 41–49 (2014).

Vicente, J., Silbiger, N. J., Beckley, B. A., Raczkowski, C. W. & Hill, R. T. Impact of high pCO2 and warmer temperatures on the process of silica biomineralization in the sponge Mycale grandis. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 73(3), 704–714 (2016).

Bates, T. E. M. & Bell, J. J. Responses of two temperate sponge species to ocean acidification. New Zeal. J. Mar. Fresh. 52(2), 247–263 (2018).

Riisgård, H. U., Thomassen, S., Jakobsen, H., Weeks, J. M. & Larsen, P. S. Suspension feeding in marine sponges Halichondria panicea and Haliclona urceolus: effects of temperature on filtration rate and energy cost of pumping. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 96(2), 177–188 (1993).

Liu, G., Feng, Q. & Gu, S. Extinction pattern and process of siliceous sponge spicules in deep-water during the latest Permian in South China. Sci. China Ser. D. 51, 1623–1632 (2008).

Clarkson, M. O. et al. Ocean acidification and the Permo-Triassic mass extinction. Science 348, 229–232 (2015).

Morrow, K. M. et al. Natural volcanic CO2 seeps reveal future trajectories for host-microbial associations in corals and sponges. ISME Journal 9, 894–908 (2014).

Fillinger, L., Janussen, D., Lundälv, T. & Richter, C. Rapid glass sponge expansion after climate-induced Antarctic ice shelf collapse. Current Biology 23, 1330–1334 (2013).

Tompkins-MacDonald, G. J. & Leys, S. P. Glass sponges arrest pumping in response to sediment: implications for the physiology of the hexactinellid conduction system. Marine Biology 154(6), 973 (2008).

Grant, N., Matveev, E., Kahn, A. S. & Leys, S. P. Suspended sediment causes feeding current arrests in situ in the glass sponge Aphrocallistes vastus. Mar. Env. Res. 137, 111–120 (2018).

Massaro, A. J., Weisz, J. B., Hill, M. S. & Webster, N. S. Behavioral and morphological changes caused by thermal stress in the great barrier reef sponge Rhopaloeides odorabile. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 416–417, 55–60 (2012).

Leys, S. The choanosome of hexactinellid sponges. Invertebr. Biol. 118, 221–235 (1999).

Ribes, M., Coma, R. & Gili, J. R. Natural diet and grazing rate of the temperate sponge Dysidea avara (Demospongiae, Dendroceratida) throughout an annual cycle. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 176, 179–190 (1999).

Leys, S. P. & Meech, R. W. Physiology of coordination in sponges. Can. J. Zool. 84, 288–306 (2006).

Marliave, J. B., Borden, L. A., Schultz, J. A., Gibbs, D. M. & Dennison, G. J. Formation, persistence, and recovery of glass sponge reefs: A case study. In Invertebrates-Ecophysiology and Management, InTechOpen: Aquatic Invertebrates. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.82325 (2018).

NOAA/National Weather Service. El Niño/Southern oscillation (ENSO) diagnostic discussion. Source, https://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/analysis_monitoring/enso_disc_mar2015/ensodisc.html (2015)

Bennett, H. M. et al. Interactive effects of temperature and pCO2 on sponges: from the cradle to the grave. Glob. Change Biol. 23, 2031–2046 (2017).

Bennett, H., Bell, J. J., Davy, S. K., Webster, N. S. & Francis, D. S. Elucidating the sponge stress response; lipids and fatty acids can facilitate survival under future climate scenarios. Glob. Change Biol. 24(7), 3130–3144 (2018).

Marliave, J. B. Cloud Sponge, Aphrocallistes vastus (Porifera: Hexactinellida), fragment healing and reattachment. Can. Field Nat. 129(4), 399–402 (2015).

Marliave, J. B., Gibbs, D. M., Young, S. & Borden, L. 2011 climate regime: revealed by seabed biodiversity. In: P.C., Chandler, S.A., King, and J., Boldt (Eds.). State of the physical, biological and selected fishery resources of Pacific Canadian marine ecosystems in 2017. Can. Tech. Rep. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 3266: viii + 245 p (2018).

Krautter, M., Conway, K. W. & Barrie, J. V. Recent hexactinosidan sponge reefs (silicate mounds) off British Columbia, Canada: frame-building processes. J. of Paleont. 80, 38–48 (2006).

Ehrlich, H. & Worch, H. Sponges as natural composites: from biomimetic potential to development of new biomaterials. In: E., Hajdu (Ed.). Porifera Research: Biodiversity, Innovation & Sustainability, 217–223 (2007).

Ehrlich, H. et al. First evidence of the presence of chitin in skeletons of marine sponges. Part II. Glass sponges (Hexactinellida: Porifera). J. Exp. Zool. Part B 308B, 473–483 (2007).

Ehrlich, H. et al. Calcite reinforced silica–silica joints in the biocomposite skeleton of the deep–sea glass sponge. Adv. Funct. Mater. 21, 3473–3481 (2011).

Chu, J. W. F. Biological patterns and processes of glass sponge reefs. MSc thesis, University of Alberta (2010).

Marliave, J. B., Conway, K. W., Gibbs, D. M., Lamb, A. & Gibbs, C. Biodiversity and rockfish recruitment in sponge gardens and bioherms of southern British Columbia, Canada. Mar. Biol. 156, 2247–2254 (2009).

Pawlik, J. R. & McMurray, S. E. The emerging ecological and biogeochemical importance of sponges on coral reefs. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 12, 3.1–3.23 (2020).

Kahn, A., Chu, J. W. F. & Leys, S. P. Trophic ecology of glass sponge reefs in the Strait of Georgia, British Columbia. Sci. Rep. 8(756), 1–11 (2018).

Peterson, B. J., Chester, C. M., Jochem, F. J. & Fourqurean, J. W. Potential role of sponge communities in controlling phytoplankton blooms in Florida Bay. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 328, 93–103 (2006).

Sunday, J. M. et al. Ocean acidification can mediate biodiversity shifts by changing biogenic habitat. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 81–86 (2017).

Harley, C. D. G. Climate change, keystone predation, and biodiversity loss. Science 334, 1124–1127 (2011).

IPCC. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, R.K. Pachauri and L.A. Meyer (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland, 151 pp. (2014).

Dickson, A. G., Sabine, C. L. & Christian, J. R. Guide to Best Practices for Ocean CO2 Measurements. PICES Special Publication 3, 191 (2007).

Pierrot, D., Lewis, E. & Wallace, D. W. R. MS Excel Program Developed for CO2 System Calculations. ORNL/CDIAC-105a. Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center. Oak Ridge National Laboratory, U.S. Department of Energy, Tennessee (2006).

Morganti, T., Yahel, G., Ribes, M. & Coma, R. VacuSIP, an improved InEx method for in situ measurement of particulate and dissolved compounds processed by active suspension feeders. JoVE 114, e54221 (2016).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL, https://www.R-project.org/ (2017).

Pinheiro, J., Bates, D., DebRoy, S., Sarkar, D. & R Core Team. nlme: Linear and Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models. R package version 3.1-139, URL, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=nlme (2019).

Zuur, A., Ieno, E. N., Walker, N., Saveliev, A. & Smith, G. Mixed Effects Models and Extensions in Ecology with R. Springer (2009).

Therneau, T. A Package for Survival Analysis in S. version 2.38, URL, https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=survival (2015).

Therneau, T. M. & Grambsch, P. M. Modeling Survival Data: Extending the Cox Model. Springer, New York. ISBN 0-387-98784-3 (2000).

Acknowledgements

This work would not have been possible without the dedicated efforts of Maya Brassard, Mikalyn Trinca Colonel, Tadhg O Corcora, Emma Foxcroft, Josianne Haag, Robert Hechler, Dr. Kyra Janot, Carli Jones, Madison Kaplan, Lauran Liggan, Dr. Colin MacLeod, and Charlotte Matthews in the lab and Donna Gibbs and Lauran Liggan in the field. We thank Sheila Byers, Glen Dennison, and Prof. Sally Leys for their insights, and Dr. Alyssa Gehman and Dr. Devin Lyons for their comments on earlier stages of the manuscript and statistical analyses. This work was supported by the MEOPAR and NSERC CREATE Training Our Future Ocean Leaders Program postdoctoral fellowships to A. Stevenson, a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council Discovery Grant and Canada Foundation for Innovation grant to C. Harley, and the Howe Sound Research and Conservation Group donors of Ocean Wise Research Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.S., S.K.A., A.D., J.B.M., C.D.G.H. devised the study. A.S. and C.D.G.H. designed the mesocosm experiments. A.S. and P.M. designed the biomechanics experiments. A.S. and J.A.S. planned and conducted field work. A.S. conducted experiments and laboratory work. A.S. wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed intellectual input, edited and approved this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Stevenson, A., Archer, S.K., Schultz, J.A. et al. Warming and acidification threaten glass sponge Aphrocallistes vastus pumping and reef formation. Sci Rep 10, 8176 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-65220-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-65220-9

This article is cited by

-

Low genetic diversity and predation threaten a rediscovered marine sponge

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Mapping cold-water coral biomass: an approach to derive ecosystem functions

Coral Reefs (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.