Abstract

Niche shifts and environmental non-equilibrium in invading alien species undermine niche-based predictions of alien species’ potential distributions and, consequently, their usefulness for invasion risk assessments. Here, we compared the realized climatic niches of four alien amphibian species (Hylarana erythraea, Rhinella marina, Hoplobatrachus rugulosus, and Kaloula pulchra) in their native and Philippine-invaded ranges to investigate niche changes that have unfolded during their invasion and, with this, assessed the extent of niche conservatism and environmental equilibrium. We investigated how niche changes affected reciprocal transferability of ecological niche models (ENMs) calibrated using data from the species’ native and Philippine-invaded ranges, and both ranges combined. We found varying levels of niche change across the species’ realized climatic niches in the Philippines: climatic niche shift for H. rugulosus; niche conservatism for R. marina and K. pulchra; environmental non-equilibrium in the Philippine-invaded range for all species; and environmental non-equilibrium in the native range or adaptive changes post-introduction for all species except H. erythraea. Niche changes undermined the reciprocal transferability of ENMs calibrated using native and Philippine-invaded range data. Our paper highlights the difficulty of predicting potential distributions given niche shifts and environmental non-equilibrium; we suggest calibrating ENMs with data from species’ combined native and invaded ranges, and to regularly reassess niche changes and recalibrate ENMs as species’ invasions progress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The large-scale redistribution of alien species – i.e., species whose presence in a region is attributed to human activities that enabled them to overcome fundamental biogeographical barriers (sensu Richardson et al.1) – is a defining feature of the Anthropocene2,3. Alien species’ invasions can alter the ecology of recipient environments4,5 and have socio-economic impacts on recipient jurisdictions6. Recognizing these impacts, world nations have committed to develop and implement science-based biosecurity policies and strategies in response to ongoing and future alien species invasions7,8, for biodiversity conservation9 and sustainability10.

Invasion risk assessments assess the ecological and socio-economic impacts of alien species’ invasions, producing the needed information to prioritize alien species and areas for biosecurity intervention7,11. Invasion risk assessment activities include predicting the potential distribution (i.e., climatically suitable areas) of invading and/or potentially invasive alien species11. These predictions can be made through ecological niche modelling (ENM; aka species distribution modelling)12,13,14,15 – a correlative statistical tool that quantifies species-environment relationships to define a species’ climatic niche16,17,18,19. Potential distributions of alien species can then be predicted by projecting ecological niche models across spatio-temporal space, enabling researchers and environmental managers to assess geographical invasion risks and identify areas where an alien species can potentially enter, establish, spread, and cause significant impacts (i.e., susceptible and sensitive sites sensu McGeoch et al.20)13. These predictions can, therefore, help in implementing effective biosecurity strategies15.

Alien species’ potential distributions are traditionally predicted based on ENMs calibrated using species’ native range data21. This approach assumes that species inhabit the entire spatial extent of climatically suitable areas in their native range (i.e., environmental equilibrium)16,22,23, and, thus, that native ENMs accurately capture the full extent of a species’ climatic niche12. Notably, this approach assumes that species’ climatic niches are conserved across space and time (i.e., niche conservatism sensu Wiens and Graham24) and, therefore, that species will only occupy areas in recipient regions that are climatically similar to those in their native range14,21,25. However, alien species have shown marked climatic niche shifts during invasion (i.e., divergence of climatic niche; sensu Broennimann et al.26), with prevalence varying across taxa (e.g., plants26,27, invertebrates28,29,30, and vertebrates31 such as amphibians32,33, birds34, reptiles32,35). Climatic niche shifts may be caused by changes in a species’ fundamental niche (i.e., the abiotic limits that define where they can persist; sensu Grinnell36) due to adaptive changes post-introduction37, changes in a species’ realized climatic niche (i.e., the subset of the fundamental niche in which a species can persist subject to dispersal limitations and biotic interactions; sensu Hutchinson38), or both, due to, for example, enemy release39. ENMs calibrated using data from the native range fail to account for climatic niche shifts and, therefore, may underpredict alien species’ potential distributions in invaded regions.

An alternative approach is to calibrate ENMs with data from a species’ invaded range, which, in theory, can capture climatic niche shifts in invading alien species26,29,40,41,42. However, most alien species’ invasions are incomplete (i.e., they have not occupied the full extent of their potential distribution), reflecting environmental non-equilibrium in the invaded range23,25,41,43. Moreover, alien species’ invasions in many parts of their invaded ranges are poorly documented or not documented at all44,45,46. To offset limitations of ENMs calibrated using data from native or invaded ranges, past studies have suggested calibrating ENMs using data from the global range (i.e., native and invaded ranges) of an alien species41,42, but this approach is also affected by data limitations in the species’ invaded ranges. These limitations of ENMs have raised doubts on their usefulness for invasion risk assessments23,40,41,42.

Quantifying and comparing alien species’ realized climatic niches in their native and invaded ranges provide insight into the extent of niche changes, enabling assessment of niche conservatism and, possibly, environmental equilibrium26,27,47. Thus, quantifying realized climatic niche changes can help assess and communicate limitations and uncertainties of ENM predictions, making it a complementary step in alien species’ ENM experiments23,27,42,47,48. Realized climatic niches can be quantified and compared in various ways, of which the most widely used methodological frameworks are the unified COUE (i.e., centroid shift, overlap, unfilling, and expansion) framework47 and the n-dimensional hypervolume framework49,50. The COUE framework was purposively developed to assess climatic niche conservatism among phylogenies and species’ populations across space and time47. The COUE framework estimates occurrence densities of two entities’ (e.g., species, populations) realized climatic niches in a gridded environmental space to decompose niche changes into three niche metrics: niche stability (i.e., the proportion of the invaded niche overlapping the native niche), niche unfilling (i.e., the proportion of the native niche non-overlapping the invaded niche), and niche expansion (i.e., the proportion of the invaded niche non-overlapping the native niche)27. Centroid shift can also be visualized from the topologies of two entities’ occurrence densities in gridded environmental space. Researchers can then compute niche overlap using a similarity index and quantitatively test alternative hypotheses of niche conservatism – niche equivalency tests whether two realized climatic niches in two ranges are equivalent or conserved in the strictest sense, whereas niche similarity tests whether two realized climatic niches are more similar than random niches48,51.

An alternative method to quantify realized climatic niches is the n-dimensional hypervolume framework49,50, which follows Hutchinson’s38 description of the fundamental niche. This method first transforms two entities’ climatic or functional (trait-based) niches into hypervolumes within a multidimensional space and, subsequently, compares hypervolumes by calculating indices of hypervolume similarity and metrics of hypervolume distance (centroid and minimum distance) and intersection (volume of intersection, unique fractions). Despite differences in the conceptual theories of the two frameworks, case studies employing both approaches are rare, although one case study of realized climatic niche shifts in an invading alien amphibian species found similar results between the two approaches33.

Here we quantified realized climatic niche changes to assess niche conservatism and environmental equilibrium of alien amphibian species in the Philippines and, subsequently, assessed the implications of niche changes for ENM predictions and their usefulness in invasion risk assessments. Six alien amphibian species have been introduced in the Philippines: the green paddy frog (Hylarana erythraea [Schlegel, 1837]) in 1880s, the cane toad (Rhinella marina [Linnaeus, 1758]) in 1930s, the American bullfrog (Lithobates catesbeianus [Shaw, 1802]) in 1960s, the Chinese bullfrog (Hoplobatrachus rugulosus [Wiegmann, 1834]) in 1990s, the Asiatic painted toad (Kaloula pulchra Gray, 1831) in 2000s, and the greenhouse frog (Eleutherodactylus planirostris [Cope, 1862]) in 2010s52,53. Pili et al.52 reviewed their invasion history and updated their current invasion status and distribution in the Philippines. Rhinella marina and L. catesbeianus were intentionally introduced in the Philippines for biocontrol and food, respectively; meanwhile, H. erythraea, H. rugulosus, K. pulchra, and E. planirostris were unintentionally introduced as a contaminant of transported commodities or stowaways on vehicles and cargo52. All species except L. catesbeianus are now fully-invasive and continue to spread across the country through leading-edge dispersal, as contaminants of transported commodities, and/or as stowaways on vehicles and cargo52. The potential ecological and socio-economic changes caused by alien amphibian species invasions54,55 emphasize the urgency for researchers and managers to assess the invasion risk of these species, to inform biosecurity7,11.

We first quantified and compared the realized climatic niches of H. erythraea, R. marina, H. rugulosus, and K. pulchra in their native ranges (native niche) and Philippine-invaded ranges (Philippine niche) to investigate climatic niche changes that may have unfolded during their invasion, and to assess niche conservatism and environmental equilibrium. We did not include L. catesbeianus and E. planirostris because of the limited data on these species in the Philippines. We quantified realized climatic niche changes using both the COUE47 and the n-dimensional hypervolume frameworks49,50. We described species climatic niches and environmental backgrounds using eight environmental variables representing a combination of means, extremes, and seasonality that are known to be ecologically relevant to amphibians and are not highly inter-correlated. We further tested for niche conservatism using niche equivalency and niche similarity tests48,51. We then investigated the implications of climatic niche changes for niche-based predictions of species’ potential distributions by calibrating ENMs using data from the Philippine-invaded (Philippine ENMs) and native ranges (native ENMs), and both ranges combined (combined range ENMs). Recognizing that different ENM approaches can yield varying predictions of potential distributions despite being calibrated with the same data (e.g., presence, absence/pseudo-absence, and environmental variables), we quantified ENMs of the four alien species using eight statistical approaches. We then created ensemble models (EMs) for each set of ENMs and used these to predict the species’ potential distributions in the Philippines and in their respective native ranges. Ensemble models identify the signals (i.e., high agreement among models) and filter the noises (i.e., high disagreement) from different ENMs, yielding a lower mean error than any of the constituent ENMs and their resulting predictions56. We related observed niche changes to aspects of the species’ invasion history in the Philippines52 and to predictions of potential distributions. We conclude with a discussion on the implications of our findings for invasion risk assessments.

We focused our niche shift analyses on the Philippines because we have a relatively robust species’ occurrence dataset on the distribution of the alien amphibians in the Philippines57. Data in other invaded ranges of these species are limited, especially for H. erythraea, H. rugulosus, and K. pulchra (data on the invaded range of R. marina is similarly poor, with the exception of Australia33). Including other invaded ranges in the analysis would therefore poorly represent the species’ global invaded niches. Importantly, including data from additional jurisdictions in which these species are alien would unlikely change our conclusions, because these additional data would be swamped by the higher number of Philippine records57.

Results

Varying levels of realized climatic niche change

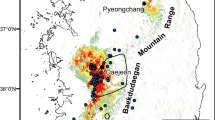

Following the COUE framework47, we first quantified the occurrence densities of the native and Philippine niches in a weighted biplot of the first two principal components (PCs) of a Principal Components Analysis (PCA) calibrated using pooled environmental backgrounds in the species’ native and Philippine-invaded ranges. The first two PCs captured ~71–76% of the variation in the environmental data. Supplementary Table S1 (online) shows the correlations between environmental variables and PCs. The topology of occurrence densities across the species’ native and Philippine niches in PC biplots revealed: that the Philippine niche of H. erythraea is a subset of its native niche, whereas the other species showed partial overlap between native and Philippine niches58; high to complete niche stability for all species at the intersection of the 75th percentile of environmental backgrounds (I75; 93–100%) and at the intersection of the complete environmental background (I100; 91–100%); low to moderate niche unfilling for all species at I75 (6–24%) and at I100 (13–30%); and zero to low niche expansion for all species at I75 (0–7%) and I100 (0–9%) (Fig. 1; Table 1). Rhinella marina and H. rugulosus showed niche expansion into non-analogous environmental space (i.e., climates found in the Philippine environmental background but not in the species’ native range environmental background). Rhinella marina, H. rugulosus, and K. pulchra shifted their niche centroids to warmer and wetter climates in the Philippines (negligible centroid shift in H. erythraea; Fig. 1; see also Supplementary Figs. S1–S4).

The native (blue) and Philippine (red) niches of Hylarana erythraea (a), Rhinella marina (b), Hoplobatrachus rugulosus (c), and Kaloula pulchra (d) as depicted by the biplot of the first two PCs. Grey areas represent overlap of the species’ native and Philippine niches. The solid and dashed contour lines respectively represent the intersection of 75% (I75) and 100% (I100) of available environments in the native range (blue) and in the Philippine-invaded range (red). Solid arrows point to the direction of centroid shift from the species’ native niches’ occurrence density centroid to the that of Philippine niche. Dashed arrows represent the distance and direction between the positions of the centroids of the occurrence density of the environmental backgrounds in the native range and the Philippines along the PC biplots. The correlation circle shows the distribution of eight environmental variables along with the PC biplot: bio 1 = annual mean temperature; bio 4 = temperature seasonality; bio 5 = maximum temperature of warmest month; bio 6 = minimum temperature of coldest month; bio 12 = annual precipitation; bio 15 = precipitation seasonality; bio 16 = precipitation of wettest quarter; bio 17 = precipitation of driest quarter.

Niche equivalency and similarity tests

Species’ native and Philippine niches showed low niche overlap (Schoener’s index of niche overlap [D]) (Table 1), with the lowest overlap in H. rugulosus (D = 0.10) and the highest in K. pulchra (D = 0.26). Comparing observed niche overlap values to null distributions (i.e., overlap values estimated from niches constructed by randomly re-allocating pooled occurrences to both niches) revealed that native and Philippine niches were more similar than expected by chance for R. marina and K. pulchra (P ≤ 0.01; Table 1; see Supplementary Fig. S5). Meanwhile, niches were more similar than randomly generated niches only for K. pulchra (P = 0.01 for both randomization methods). There was also a trend toward the niches of H. erythraea and R. marina being more similar than randomly generated niches for one of the two types of niche similarity tests (P = 0.06 for N ↔ P randomization test). For the case of H. rugulosus, niche equivalency was rejected, whereas the results of the two niche similarity tests were inconclusive. We further quantified climatic niche changes using four (for H. erythraea) to five (for R. marina, H. rugulosus, and K. pulchra) PCs to explore alternative PC biplots (see Supplementary Figs. S6–9 and Tables S2).

Dissimilar multidimensional hypervolumes of realized climatic niches

We compared species’ native and Philippine niches using the n-dimensional hypervolume framework49,50. Here, we quantified the native and Philippine niches using multidimensional hypervolumes, derived from four (for H. erythraea) to five (for R. marina, H. rugulosus, and K. pulchra) PCs used in the COUE framework. Examining the topology and geometry of the hypervolumes of the native and Philippine niches in multidimensional environmental space revealed: low similarity at both the 75th percentile probability boundary of hypervolumes (H75; Jaccard Similarity Index J = 0.04–0.18) and entire probability boundary of hypervolumes (H100; J = 0.11–0.24); low to moderate intersection at both H75 (4.73–18.38%) and H100 (11.22–22.37%); varying levels of unique fractions of the Philippine niche at H75 (15–81%) and H100 (8–57%); short centroid distances in H. erythraea at H75 (0.24) and H100 (0.62) relative to the other species (1.23–1.66 at H75; 1.30–1.80 at H100); and short minimum distances between hypervolumes at H75 (0.05–0.15) and H100 (0.11–0.17) (Figs. 2–3; Table 2; see Supplementary Figs. S10–13).

The hypervolumes of the native niche (blue) and Philippine niche (red) of Hylarana erythraea (a) and Rhinella marina (b) in multidimensional environmental space defined by four (for H. erythraea) to five (for R. marina) PCs. The solid contour lines represent the entire boundary of hypervolumes(H100). The filled circles represent the centroids of the hypervolumes of the native niche (blue) and Philippine niche (red). Opaque dots represent true species’ occurrence records, whereas transparent dots represent random records derived from Gaussian kernel density estimation.

The hypervolumes of the native niche (blue) and Philippine niche (red) of Hoplobatrachus rugulosus (a) and Kaloula pulchra (b) in multidimensional environmental space defined by five PCs. The solid contour lines represent the 100% percentile probability boundary of hypervolumes(H100). The filled circles represent the centroids of the hypervolumes of the native niche (blue) and Philippine niche (red). Opaque dots represent true species’ occurrence records, whereas transparent dots represent random records derived from Gaussian kernel density estimation.

Undermined performance of native and Philippine EMs

Ensemble models of Philippine ENMs (Philippine EMs) predicted high climatic suitability in many areas in the Philippines where the species are known to occur (Figs. 4–7). This was supported by the scores of the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC) and by True Skill Statistics (TSS) derived from projecting Philippine EMs to the evaluation dataset (Eeval; see methods), wherein AUC scores were fair (H. erythraea, H. rugulosus) to good (R. marina, K. pulchra), and TSS scores were consistently high (>0.50) (Table 3; see Supplementary Figs. S14–17). In contrast, the Philippine EMs of all species underpredicted climatically suitable areas in the native range (Figs. 4–7). The AUC of the Philippine EMs, when projected to the species’ presence/pseudo-absence dataset in the native range (Enat), ranged from failed (R. marina and H. rugulosus) to poor (H. erythraea and K. pulchra), whereas TSS scores were slightly better than random (Table 3; see Supplementary Figs. S14–17). Projecting values of environmental variables in the Philippines to those in species’ native ranges revealed vast extents of clamping of several environmental variables – predictions in these areas are therefore uncertain (see Supplementary Figs. S18–21).

Predicted potential distribution of Hylarana erythraea in its native range and in the Philippines (columns) projected by EMs calibrated using data from the Philippine-invaded range, native range, and combined ranges (rows). Hylarana erythraea is native to South Asia, mainland Southeast Asia, and parts of maritime Southeast Asia (Borneo, Indonesia [Sumatra, Java, Lombok, and Riau Islands]). White dots represent species occurrence records, which were thinned to improve visibility. Relative climatic suitability increases from cold to warm colours. The maps were created using QGIS Geographic Information System software (v. 3.14; http://qgis.osgeo.org) and projected using WGS 1984 Coordinate Reference System.

Predicted potential distribution of Rhinella marina in its native range and in the Philippines (columns) projected by EMs calibrated using data from the Philippine-invaded range, native range, and combined ranges (rows). Rhinella marina is native to tropical Americas. White dots represent species occurrence records, which were thinned to improve visibility. Relative climatic suitability increases from cold to warm colours. The maps were created using QGIS Geographic Information System software (v. 3.14; http://qgis.osgeo.org) and projected using WGS 1984 Coordinate Reference System.

Predicted potential distribution of Hoplobatrachus rugulosus in its native range and in the Philippines (columns) projected by EMs calibrated using data from the Philippine-invaded range, native range, and combined ranges (rows). Hoplobatrachus rugulosus is native to East Asia (China and Taiwan) and mainland Southeast Asia. White dots represent species occurrence records, which were thinned to improve visibility. Relative climatic suitability increases from cold to warm colours. The maps were created using QGIS Geographic Information System software (v. 3.14; http://qgis.osgeo.org) and projected using WGS 1984 Coordinate Reference System.

Predicted potential distribution for Kaloula pulchra in their native range and in the Philippines (columns) projected by EMs calibrated using data from the Philippine-invaded range, native range, and combined ranges (rows). Kaloula pulchra is native to Southern East Asia (China), eastern South Asia (Bangladesh and India), mainland Southeast Asia, and some parts of maritime Southeast Asia (Singapore and Indonesia [Sulawesi]). White dots represent species occurrence records, which were thinned to improve visibility. Relative climatic suitability increases from cold to warm colours. The maps were created using QGIS Geographic Information System software (v. 3.14; http://qgis.osgeo.org) and projected using WGS 1984 Coordinate Reference System.

Ensemble models of native ENMs (native EMs) predicted low climatic suitability in many areas in the Philippines where the species are known to occur (Figs. 4–7). Projecting native EMs to the species’ presence/pseudo-absence dataset in the Philippine-invaded range (Einv) produced AUC scores ranging from no better than random (H. rugulosus), failed (R. marina and K. pulchra), to poor (H. erythraea), whereas TSS scores ranged from no better than random (H. rugulosus) to slightly better than random (Table 3; see Supplementary Figs. S14–17). Interestingly, native EMs predicted high climatic suitability in extensive areas in the Philippines that the species have not yet invaded. In contrast, native EMs produced good predictions of the species’ native range (Figs. 4–7). When projected to its Eeval dataset, the native EMs of all species scored fair (H. erythraea), good (R. marina), to excellent (H. rugulosus, K. pulchra) AUC values, and high TSS scores (Table 3; see Supplementary Figs. S14–17). Projecting values of environmental variables in the species’ native ranges to those in the Philippines revealed vast extents of clamping of several environmental variables (see Supplementary Figs. S18–21).

When projected to the Philippines and the native range, EMs of combined range ENMs (combined range EMs) predicted high climatic suitability in many areas where the species are known to occur, as well as in areas in the Philippines where the species have not yet invaded (Figs. 4–7). When projected to Einv and Enat, the combined-range EMs of all species had fair to excellent AUCs. Meanwhile, the combined-range EMs of most species had lower TSS when projected to Einv and Enat relative to Eeval (Table 3; see Supplementary Figs. S14–17). Projecting values of environmental variables in the species’ combined ranges to either their native range or the Philippines revealed negligible clamping of environmental variables.

Discussion

Our findings revealed varying levels of niche change across four alien amphibian species introduced to the Philippines: high niche stability and low to moderate niche unfilling across all species, and insignificant to substantial niche expansion in all species except H. erythraea. All species except H. erythraea occupied hotter and wetter climates in the Philippines. Niche overlap was low for all species. Despite the low overlap, niche equivalency tests revealed niche conservatism in R. marina and K. pulchra, and niche similarity tests revealed niche conservatism in K. pulchra and to a lesser extent in R. marina and H. erythraea. The native and invaded niches of H. rugulosus were not equivalent, although niche similarity tests were inconclusive. Nonetheless, niche expansion in analogous (i.e., climates found in both the Philippines and each species’ native range) and non-analogous environmental space provide evidence of niche shift in H. rugulosus. Niche unfilling revealed environmental non-equilibrium in the Philippine-invaded range for all species, whereas niche expansion revealed environmental non-equilibrium in the native range and/or adaptation in the invaded range for all species except H. erythraea. Hypervolume centroid distances consistently supported a shift in the niche centroids of all species except H. erythraea. Meanwhile, hypervolume intersection metrics generally revealed substantial unique fractions of Philippine niches, which is overall inconsistent with the findings of the COUE niche change metrics. Consistent with the findings of the niche overlap tests based on Schoener’s D, values of Jaccard hypervolume similarity index were consistently low for all species. Finally, we found that native and Philippine EMs showed poor reciprocal transferability – that is, climatic characteristics of the Philippine niche poorly predicted the potential distribution of the species in the native range, and vice versa. Combined range EMs produced relatively better predictions of potential distributions across both native and invaded ranges.

Our findings build on previous studies32,33, contributing to our growing understanding of climatic niche changes during the invasion of alien species, in general, and alien amphibian species, in particular. Our study is the first to assess niche changes in H. erythraea, H. rugulosus, and K. pulchra. Meanwhile, our findings of niche conservatism in the Philippine-invaded range of R. marina is somewhat consistent with the findings of Li et al.32 – that is, the realized climatic niche of R. marina is conserved in its Indomalayan invaded range (including the Philippines); our findings showed niche equivalency and to a lesser extent similarity in R. marina in its Philippine-invaded range (Table 1), whereas Li et al.32 showed niche similarity (P = 0.02; niche equivalency test was not conducted) in its Indomalayan invaded range. The inconsistent results of the niche similarity test between our study and Li et al.32 were likely driven by the differences in the scale and geographic extent of our analysis (Philippines only vs. Indomalayan realm, respectively). Our study also extends the work of Tingley et al.33, who examined niche shifts across the native vs. Australian-invaded range of R. marina.

The observed niche shifts could either be due to shifts in the species realized climatic niches in their invaded ranges27, to a shift in the species’ fundamental niches (e.g., changes in their environmental tolerances) during the course of invasion26,37, or both. Realized climatic niche shift is in line with the notion that species occupy a subset of their fundamental niche in their native range – indicating environmental non-equilibrium – due to dispersal limitations and/or biotic interactions59,60. In contrast, fundamental niche shift may be caused by adaptive changes post-introduction37. In the case of R. marina, we detected expansion of the species’ Philippine niche into analogous and non-analogous environments. Phenotypic changes have been observed over the course of the species’ invasion in Australia61,62. However, Tingley et al.33, by combining ecophysiological and correlative models, found that R. marina fails to occupy a substantial fraction of its fundamental niche in its native South American range, plausibly due to biotic interactions with closely related species. More importantly, they showed that R. marina has successfully filled its fundamental niche in its Australian-invaded range, reflecting realized climatic niche shift. In our analysis, the captured environmental backgrounds in the native range (derived from biomes intersecting the species’ range) are likely more environmentally restricted than the fundamental niche, and the detected non-analogous climates in the Philippines are likely within the species’ fundamental niche. Meanwhile, for H. rugulosus, discriminating whether realized or fundamental niche shift explains the observed niche expansion in non-analogous environmental space would require mechanistic approaches based on experimental measurements of the species’ fundamental niche26,33,63.

We extended our main analysis by quantifying niche changes in the COUE framework47 using alternative biplots constructed from combinations of the first four to five PCs. Interestingly, alternative biplots revealed inconsistent support for niche equivalency and similarity, and in some cases, high variance in niche change metrics (see Supplementary Table S2). Nonetheless, we argue that the biplots of the first two PCs, as presented here, provide the most reliable results, since they explain the highest amount of variation in the environmental data (>71%). The fact that the COUE framework is limited to analysing niches in two dimensions at a time is a significant limitation. To overcome this limitation, we further quantified species’ climatic niche changes using the n-dimensional hypervolume framework49,50. Using four to five PCs that collectively captured ~99% variance in the environmental data, our findings again revealed varying levels of niche changes among species, which were generally inconsistent with our findings derived using COUE framework’s niche change metrics. This highlights the difficulty of quantifying niche changes, as well as testing for niche conservatism and shift, due to varied conceptual theories underpinning different methodological frameworks. Nonetheless, the n-dimensional hypervolume framework, as currently implemented, does not account for environmental availability in each range (and thus analogous and non-analogous environments) and does not give greater weight to PCs that explain more environmental variation. To this end, we base our conclusions regarding niche conservatism and environmental equilibrium primarily from the findings revealed by the COUE framework.

Should we anticipate future niche changes in the four alien amphibian species’ Philippine niches? We found niche unfilling for all species, revealing environmental non-equilibrium in the species’ Philippine niches. This supports the findings of Pili et al.52 that all species’ invasions in the Philippines are incomplete, and that the species continue to spread. Moreover, for all species, PC biplots revealed analogous environmental space that is unoccupied in both native and Philippine-invaded ranges. If accessible (in geographic space) and climatically suitable, these areas of environmental space present opportunities for future niche expansion. For H. rugulosus, PC biplots revealed unoccupied non-analogous environmental space in the Philippines, which presents opportunities for the species to further shift its Philippine niche. This emphasizes the need for regular reassessments of niche conservatism/shift as a species’ invasion progresses.

Our findings do not conform to observed patterns linking niche unfilling with aspects of species’ invasion history. Patterns in alien amphibian32, reptile32, and bird31 invasions showed that residency time (i.e., the length of time since a species was first introduced) is inversely correlated with the magnitude of niche unfilling. Our findings regarding R. marina, which was introduced in the Philippines in 193452, are somewhat conforming with this pattern. Meanwhile, the other species showed an inverse pattern; for example, H. rugulosus and K. pulchra, respectively introduced only in the 1990s and 2000s52, showed low levels of niche unfilling, whereas H. erythraea showed substantial niche unfilling, despite being first introduced in the Philippines for more than a century ago in the 1880s52.

Niche unfilling in birds31 and in alien species in disjunct geographic areas (e.g., archipelagic systems)33 have been linked to dispersal limitations (e.g., biogeographic barriers)64 and propagule pressure (i.e., the absolute number of individuals involved in a human-mediated dispersal event and the number of discrete dispersal events)59. Similarly, the high niche unfilling in H. erythraea observed here may be due to its dependence on pathways characterized by low inter-island propagule pressure, especially during the early periods of its invasion. Hylarana erythraea is known to historically disperse inter-island primarily as a contaminant of commodities (agriculture, animals) (sensu Scalera et al.65)52. The trade of these commodities (reflecting propagule pressure) is high intra-islands, especially on larger Philippine islands such as Luzon and Mindanao, where rapid and short-distance transport is possible and is critical for such perishable commodities. However, inter-island trade of these commodities is low, likely limiting the species dispersal throughout the archipelago. This low level of propagule pressure coincides with its spatio-temporal spread in the Philippines, in which it was first introduced and restricted among import-dependent small islands in the Central Philippines for more than a century, and only dispersed to the country’s major islands of Luzon and Mindanao in the 1990s, where it underwent an increased rate of spread52. Meanwhile, high propagule pressure was likely an important contributor to the low levels of niche unfilling in R. marina, H. rugulosus, and K. pulchra. Rhinella marina was initially intentionally dispersed in many parts of the Philippines as a biological control agent, where it subsequently dispersed intra-islands primarily via natural dispersal. Moreover, the rapid inter-island dispersal of R. marina has been attributed to the Philippines’ dependence on sea transport for trade and travel – this species has been observed to hitchhike on transportation vehicles (e.g., ships, boats, trucks)52. The use of multiple alternative introduction and dispersal pathways – providing alternative ways for intra- and inter-island dispersal – likely aided H. rugulosus and K. pulchra in negating effects of residency time and dispersal limitations, resulting in rapid dispersal throughout the country52.

Predictions of native EMs corroborated previous studies showing that ENMs based on the native range of species often underpredict suitable areas in the invaded range26,29,40,41,42. Specifically, native EMs predicted low climatic suitability in many areas in the Philippines where the species occur. The observed poor predictive performance of native EMs was likely caused by the observed niche expansion and unfilling in the species Philippine niches. Interestingly, our findings, especially for H. erythraea, support previous studies31,35 showing increased predictive performance of native ENMs with decreasing niche unfilling and expansion in the invaded range. Meanwhile, Philippine EMs support previous studies showing ENMs calibrated using invaded range data may be able to capture niche shifts that occurred during invasion26,29,40,41,42. However, due to environmental non-equilibrium often observed in alien species in their invaded ranges, ENMs calibrated using invaded range data may fail to capture parts of the species’ climatic niche that is occupied in the native range but unoccupied in the invaded range. This leads to underprediction of the species’ potential distribution in both the native and invaded ranges22,23,25,41, as observed in the predictions of the Philippine EMs. Overall, combined range EMs predicted high climatic suitability in areas in the Philippines where the species are known to occur, and predicted areas that are climatically suitable but are yet uninvaded by the species. Our findings corroborate those of previous studies in that combining data from the native and invaded ranges of an alien species, where available, can offset the predictive limitations of ENMs calibrated in only the native or invaded ranges26,29,40,41,42. We recommend future researchers recalibrate combined range EMs as species’ invasions progress, and when data from other ranges of the species are collected and/or made available.

Conclusion

Overall, our findings revealed evidence of conservatism in the Philippine niches of R. marina and K. pulchra, and a shift in the Philippine niche of H. rugulosus. Meanwhile, for H. erythraea, the extent to which the species’ niche has been conserved is less clear. Different aspects of species’ invasion history, such as residency time, dispersal limitation, and propagule pressure, can only partially explain the observed changes in the species’ Philippine niches. The observed niche changes, reflecting niche conservatism/shifts and environmental non-equilibrium, likely caused the observed poor reciprocal transferability of native and Philippine EMs and their constituent ENMs. Our findings support previous studies showing that ENMs calibrated with data from the combined native and invaded ranges, where available, will be most useful in informing invasion risk assessments22,23,35,41,66. In light of the implications of niche shifts and environmental non-equilibrium for ENM predictions, we suggest researchers and managers routinely incorporate quantification of niche changes into ecological niche modelling experiments23,27,42,47,48. In addition, the fact that the majority of alien species’ invasions are incomplete23,25,41,43, such as the case of the four alien amphibian species studied here, emphasizes the need for researchers and managers to regularly reassess niche changes in alien species’ invaded ranges as a species’ invasion progress33. Consequentially, ENMs must be regularly recalibrated with updated data to reflect concurrent changes in the species’ realized climatic niche in the invaded range33,40,58.

Materials and Methods

Species occurrence and environmental data

Occurrence records of the four alien amphibian species in the Philippines and the species’ native ranges were obtained from the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF)67, collections of local natural history institutions, scientific publications, expert observations, and field surveys conducted by the authors (see Supplementary Methods)57. The pooled dataset was cleaned manually so that only high-quality records were used in the analysis; records conforming to these set of conditions were retained: (1) georeferenced; (2) with year of record; (3) with “county” or “municipality” locality data (sensu Darwin Core Task Group68); (4) inland coordinates and within the ascribed locality (up to the third administrative level [admin2] of the Global Administrative Areas v3.6 [https://gadm.org/]) – assessed in InfoXY v.2 tool of speciesLink (http://splink.cria.org.br/); (5) and inside the known native range of the species, as depicted by species range maps69,70,71,72. To minimize spatial sampling bias, occurrence records were thinned by subsampling records to a resolution of one record per 5 km2 (2.5 arc-min)73,74. Initial visual assessment of the spatial distribution of the records of R. marina showed sampling bias across its native range, where records were denser in Central America relative to other parts of its range. Thus, we further reduced native-range records of R. marina to a resolution of 10 km2 (5 arc-min)33. We initially planned to omit occurrence data outside the years 1970–2000, to align with the temporal reference of the environmental variables (described below)75. However, this would have resulted in the omission of a considerable proportion of collected occurrence data (~60–100%), especially data on recent range expansions of the species in the Philippines (K. pulchra was first recorded in the 2000s), and would inevitably negatively affect our analysis of realized climatic niche changes and our modelling of species’ ecological niches. In addition, after our extensive data cleaning process, the final thinned dataset only contained data recorded from 1950 to present (Table 4).

Environmental variables

Extreme temperature and precipitation can negatively affect amphibian development (e.g., tadpole and egg developmental rates/morbidity), ecophysiology (e.g., locomotor performance, communication, sensory systems), and energy acquisition and allocation76,77,78. Temperature and precipitation seasonality alter growth, reproductive cycles, phenology, and prey-predator dynamics79,80,81,82. At a broad geographical scale, precipitation and temperature extremes and seasonality influence amphibian biogeography (population declines and extirpations, shifts in geographic distribution, species extinction)83,84,85. Thus, in quantifying realized climatic niche changes and ecological niche modelling, we used environmental variables representing a combination of means, extremes, and seasonality that are known to be ecologically relevant to amphibians and are not highly inter-correlated (Pearson’s correlation coefficient |r | ≤ 0.7)86: annual mean temperature (bio 1), temperature seasonality (bio 4), maximum temperature of the warmest month (bio 5), minimum temperature of the coldest month (bio 6), annual precipitation (bio 12), precipitation seasonality (bio 15), precipitation of the wettest quarter (bio 16), and precipitation of the driest quarter (bio 17). Bioclimatic variables were obtained from WorldClim v.2, and represent averages of monthly minimum, mean, and maximum temperature and of precipitation for 1970-200075 with a spatial resolution of 5 km2 (2.5 arc-minutes).

Quantifying niche changes

We quantified the native and Philippine niches of the four alien amphibian species using the COUE framework47 and the n-dimensional hypervolume framework49,50. We then tested for niche equivalency and similarity between the native and Philippine niches of the species48,51. Finally, we assessed for niche conservatism and environmental equilibrium based on findings of the methodological frameworks and niche equivalency and similarity tests.

COUE Approach

Using the COUE framework47, we quantified the species’ native and Philippine niches in weighted PC biplots and decomposed climatic changes in species’ niche using a unified set of metrics27,47. We analyzed this using the ecospat package87 in R v.3.688. We first transformed each species’ global environmental space based on the eight environmental variables described above, onto a biplot defined by the first two PCs of a PCA. We calibrated the PCA using pooled environmental backgrounds from the species’ native and Philippine ranges. We defined ecologically relevant environmental backgrounds following the suggestions of Guisan et al.47. In the native range, environmental backgrounds include all the biomes89 inhabited by the species (i.e., biomes that are intersected by the species’ native range69,70,71,72). In the Philippines, environmental backgrounds included the whole of the Philippines. The first two PCs captured ~71–76% of the variation in the environmental data. The correlations of environmental variables with the PCs are shown in Supplementary Table S1 (online). We then divided the species’ global environmental space, as depicted in a PC biplot, into a grid consisting of 100 ×100 cells, bounded by the minimum and maximum values in the environmental background. Lastly, we projected the scores of the species occurrence records onto the gridded environmental space and grouped the scores per grid cell. We applied a Gaussian kernel density function with a standard bandwidth to estimate the smoothed density of occurrences in each cell of the gridded environmental space90. We further quantified the species realized climatic niche using alternative biplots from combinations of the first four (for H. erythraea) to five (for R. marina, H. rugulosus, and K. pulchra) PCs (see Supplementary Figs. S6–9).

We visually examined the niches’ occurrence densities in gridded environmental space, as depicted in a PC biplot, and categorized their topological interaction into five possible patterns58: (1) complete to near-complete overlap of the two niches; (2) the Philippine niche is a subset of the native niche; (3) native niche is a subset of the Philippine niche; (4) partial overlap between the two niches; or (5) completely disjunct niches. We decomposed niche changes in analogous environmental space into niche stability, niche expansion, and niche unfilling27,47. We calculated these indices in I75 (to remove marginal climates resulting from kernel smoothing) and I100 of environments available in each range. These indices are not confounded by non-analogous climates, making measured expansion indicative of changes in the realized niche27. Thus, we also visually assessed niche unfilling and expansion in non-analogous environmental space.

Niche overlap, equivalency, and similarity

We quantified the overlap between each species’ native and Philippine niches using Schoener’s index D of niche overlap91, which estimates the overall similarity between the two niches over the global environmental space51. Schoener’s D ranges from zero (no overlap) to one (complete overlap)51,91]. We quantified niche conservatism by testing estimates of D under two alternative hypotheses, representing two extremes across a spectrum of niche conservatism: (1) niche equivalency which determines whether realized niches of two entities in two geographical ranges are conserved in the strictest sense (i.e., whether observed niche overlap is effectively indistinguishable when randomly re-allocating pooled occurrences of both niches between them), and (2) niche similarity, which estimates whether the realized niche occupied in one range is more similar to the niche occupied in the other range than randomly generated niches48,51

For each species, we tested the hypothesis of niche equivalency by simulating two niches based on randomly permuted pooled occurrence records of the native and Philippine niches (the simulated niches maintain the same number of occurrence records as that observed between the native and Philippine niches). The overlap between the two simulated niches was then estimated using Schoener’s D. This process was repeated 1,000 times to generate a null distribution of niche overlap values of simulated randomly permuted niches and to confidently reject/accept the hypothesis of niche conservatism. We inferred niche conservatism if the observed niche overlap was greater than 95% of null distribution values (using the “greater” test of ecospat.niche.equivalency.test function in the ecospat package, which is a one-tailed test). In contrast, observed values outside the density of 95% of null distributions suggest a significant difference in niches48,51.

We tested for niche similarity by simulating two niches based on occurrence densities with randomly placed centroids in the environmental background using two randomization tests: (1) centroids randomly placed in both the native and Philippine range (N ↔ P) and (2) centroid randomly placed in the Philippine-invaded range only (N → P)48,51. The simulated niches maintain the same number of occurrence records as that observed between the native and Philippine niches. This process was repeated 1,000 times, randomly shifting the centroid of simulated occurrence densities in each repeat, to generate a null distribution of niche overlap values of simulated random niches and to confidently reject/accept the hypothesis of niche conservatism. We inferred niche conservatism if the observed overlap value was greater than 95% of null distribution values (using the “greater” test of ecospat.niche.similarity.test function in the ecospat package)48,51.

n-dimensional hypervolume framework

We analysed the multidimensional hypervolumes of species’ native and Philippine niches using the hypervolume package92 in R v.3.688. Using the Gaussian kernel density estimation method, we generated multidimensional hypervolumes of species native and Philippine niches from homogeneously distributed random records. These random records were derived from the Gaussian kernel density estimates of the distributions of species’ occurrence records in multidimensional environmental space comprising of the same four (for H. erythraea) to five (for R. marina, H. rugulosus, and K. pulchra) PCs used in the COUE framework, which collectively capture ~99% of variation in environmental data. The bandwidth for Gaussian kernel density estimates was estimated separately for each species niche using the Silverman bandwidth estimator (see Supplementary Table S3)89. The hypervolumes of the species’ native and Philippine niches were compared using a similarity index (Jaccard) and niche changes were decomposed using hypervolume distance (minimum distance, centroid distance) and intersection (volume of the intersection, the unique fraction of hypervolumes) metrics93. We calculated the hypervolume metrics and similarity index in H75 (to remove marginal climates resulting from kernel smoothing) and in H100.

Ecological niche modelling

We modelled the realized climatic niches of the four alien amphibian species using eight statistical approaches: (1) Generalized Additive Model (GAM)94, (2) Generalized Linear Model (GLM)95, (3) Multivariate Adaptive Regression Splines (MARS)96; a classification technique – (4) Classification and Regression Trees (CART)97; machine learning techniques –(5) Artificial Neural Networks (ANN)98, (6) Random Forests (RF)99, (7) Boosted Regression Trees (BRT)100, and (8) Maximum Entropy (Maxent)101. We calibrated ENMs with the same eight environmental variables used to quantify the realized climatic niche changes and occurrence records from the species’ (1) Philippine-invaded range, (2) native range, and (3) combined ranges. We tested for environmental variable clamping to identify locations where values of variables were outside the range used for calibrating ENMs – predictions in these areas are uncertain. This was done by projecting values of environmental variables from one range to another (e.g., the Philippines to species’ native range). Barbet-Massin et al.102 laid-out optimal settings in generating and weighting pseudo-absences for different statistical techniques used in ENM. Here, we generated and weighted pseudo-absences to yield good to optimal ENM performance across the eight statistical techniques102. We generated pseudo-absence data by randomly sampling 10,000 background points from areas where the species has no presence records and across all the biomes89 inhabited by the species (same environmental backgrounds used in COUE framework). For each statistical approach, we equally weighted the presences and pseudo-absences used to calibrate the ENMs by setting a neutral (0.5) prevalence. We conducted the analysis using the biomod2 package103,104 in R v.3.688. We ran all ENMs with the default parameters of the statistical techniques.

Prior to modelling, we randomly split each presence/pseudo-absence dataset (datasets for native, Philippine, and combined range ENMs) into two parts: 70% for training and 30% for evaluation (Eeval). By assigning a specific subset for evaluation, the EMs (discussed below) and its constituent ENMs were evaluated using the same data, ensuring a fair evaluation between the performances of EMs compared to ENMs104. For each species, we further sub-sampled the training data subset randomly to 70% training and 30% testing. This was repeated 10 times to account for uncertainty due to random subset selection, resulting in 10 random sub-samples of training-testing data. We modelled each sub-sample of training-testing data using the eight statistical approaches described above, generating 80 Philippine ENMs, 80 native ENMs, and 80 combined ENMs per species.

To evaluate predictive performance, we projected the ENMs to their respective Eeval. To evaluate reciprocal transferability, we projected the Philippine ENMs to the entire presence/pseudo-absence dataset in the native range (Enat), native ENMs to the entire presence/pseudo-absence dataset in the Philippine-invaded range (Einv), and combined ENMs to both Enat and Einv. We then computed for the AUC105 and the TSS106. We interpreted the AUC values based on Swets et al.107, where values >0.90 = excellent, >0.80–0.90 = good, >0.70–0.80 =fair, >0.60–0.70 = poor, and >0.50–0.60 = fail. Meanwhile, TSS values range from –1 to 1, where 1 indicates perfect agreement and values zero or less indicate performance no better than random106.

For each species, we combined each set of ENMs (80 Philippine ENMs; 80 native ENMs; 80 combined ENMs) to build a consensus ensemble model where each ENM was weighted by its TSS scores (i.e., better performing models contribute more to the EM)56,104. We then evaluated the EMs using the evaluation datasets used in evaluating their constituent ENMs (Eeval and Enat for Philippine EMs; Eeval and Einv for native EMs; Eeval, Einv, and Enat for combined range EMs). To predict species’ potential distributions, we projected species’ EMs to the Philippines and their respective native ranges.

Data availability

All data was gathered from publicly available sources and are available in the online registry of the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (HerpWatch Pilipinas, Inc.;57 see Supplementary Methods).

References

Richardson, D. M., Pysek, P. & Carlton, J. T. In Fifty Years of Invasion Ecology: The Legacy of Charles Elton (ed David M. Richardson) Ch. 30, 409-420 (2011).

Lewis, S. L. & Maslin, M. A. Defining the anthropocene. Nature 519, 171–180, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14258 (2015).

Crutzen, P. J. Geology of mankind. Nature 415, 23, https://doi.org/10.1038/415023a (2002).

Mooney, H. A. & Cleland, E. E. The evolutionary impact of invasive species. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98, 5446–5451, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.091093398 (2001).

Vila, M. et al. Ecological impacts of invasive alien plants: a meta-analysis of their effects on species, communities and ecosystems. Ecol Lett 14, 702–708, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01628.x (2011).

Pejchar, L. & Mooney, H. A. Invasive species, ecosystem services and human well-being. Trends Ecol Evol 24, 497–504, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2009.03.016 (2009).

Wittenberg, R., & Cock, M. J. (eds.). Invasive alien species: a toolkit of best prevention and management practices., (CABI, 2001).

Clout, M. N., Williams, P. A. (eds.). Invasive Species Management: A Handbook of Principles and Techniques. 308 (Oxford University Press, 2009).

Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). The strategic plan for biodiversity 2011-2020 and the aichi biodiversity targets. Report No. UNEP/CBD/COP/DEC/X/2, (2010).

United Nations (IUCN). Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. Resolution adopted by the General Assembly. Report No. A/RES/70/1, (2015).

Stohlgren, T. J. & Jarnevich, C. S. In Invasive Species Management. A Handbook of Principles and Techniques (ed M.N. Clout, Williams, P. A.) 19–35 (Oxford University Press, 2009).

Peterson, A. T. & Vieglais, D. A. Predicting Species Invasions Using Ecological Niche Modeling: New Approaches from Bioinformatics Attack a Pressing Problem. BioScience 51, 10.1641/0006-3568(2001)051[0363:Psiuen]2.0.Co;2 (2001).

Jiménez-Valverde, A., Lobo, J. M. & Hortal, J. Not as good as they seem: the importance of concepts in species distribution modelling. Diversity and Distributions 14, 885–890, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-4642.2008.00496.x (2008).

Jeschke, J. M. & Strayer, D. L. Usefulness of bioclimatic models for studying climate change and invasive species. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1134, 1–24, https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1439.002 (2008).

Venette, R. C. E. Pest risk modelling and mapping for invasive alien species. (Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International, 2015).

Guisan, A. & Zimmermann, N. E. Predictive habitat distribution models in ecology. Ecological Modelling 135, 147–186, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-3800(00)00354-9 (2000).

Franklin, J. Mapping species distributions: spatial inference and prediction. (Cambridge University Press, 2010).

Peterson, A. T., et al Ecological niches and geographic distributions (MPB-49) Vol. 56 (Princeton University Press, 2011).

Guisan, A., Thuiller, W., & Zimmermann, N. E. Habitat suitability and distribution models: with applications in R. (Cambridge University Press, 2017).

McGeoch, M. A. et al. Prioritizing species, pathways, and sites to achieve conservation targets for biological invasion. Biological Invasions 18, 299–314, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10530-015-1013-1 (2015).

Peterson, A. T. Predicting the Geography of Species’ Invasions via Ecological Niche Modeling. The Quarterly Review of Biology 78, 419–433, https://doi.org/10.1086/378926 (2003).

Araújo, M. B. & Pearson, R. G. Equilibrium of species’ distributions with climate. Ecography 28, 693–695, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2005.0906-7590.04253.x (2005).

Araújo, M. B., Pearson, R. G., Thuiller, W. & Erhard, M. Validation of species–climate impact models under climate change. Global Change Biology 11, 1504–1513, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2005.01000.x (2005).

Wiens, J. J. & Graham, C. H. Niche Conservatism: Integrating Evolution, Ecology, and Conservation Biology. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 36, 519–539, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.36.102803.095431 (2005).

Elith, J. & Leathwick, J. R. Species Distribution Models: Ecological Explanation and Prediction Across Space and Time. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 40, 677–697, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.110308.120159 (2009).

Broennimann, O. et al. Evidence of climatic niche shift during biological invasion. Ecol Lett 10, 701–709, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2007.01060.x (2007).

Petitpierre, B. et al. Climatic niche shifts are rare among terrestrial plant invaders. Science 335, 1344–1348, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1215933 (2012).

Medley, K. A. Niche shifts during the global invasion of the Asian tiger mosquito,Aedes albopictusSkuse (Culicidae), revealed by reciprocal distribution models. Global Ecology and Biogeography 19, 122–133, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-8238.2009.00497.x (2010).

Fitzpatrick, M. C., Weltzin, J. F., Sanders, N. J. & Dunn, R. R. The biogeography of prediction error: why does the introduced range of the fire ant over-predict its native range? Global Ecology and Biogeography 16, 24–33, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-822X.2006.00258.x (2006).

Hill, M. P., Gallardo, B. & Terblanche, J. S. A global assessment of climatic niche shifts and human influence in insect invasions. Global Ecology and Biogeography 26, 679–689, https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12578 (2017).

Strubbe, D., Beauchard, O. & Matthysen, E. Niche conservatism among non-native vertebrates in Europe and North America. Ecography 38, 321–329, https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.00632 (2015).

Li, Y., Liu, X., Li, X., Petitpierre, B. & Guisan, A. Residence time, expansion toward the equator in the invaded range and native range size matter to climatic niche shifts in non-native species. Global Ecology and Biogeography 23, 1094–1104, https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12191 (2014).

Tingley, R., Vallinoto, M., Sequeira, F. & Kearney, M. R. Realized niche shift during a global biological invasion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111, 10233–10238, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1405766111 (2014).

Strubbe, D., Broennimann, O., Chiron, F. & Matthysen, E. Niche conservatism in non-native birds in Europe: niche unfilling rather than niche expansion. Global Ecology and Biogeography 22, 962–970, https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12050 (2013).

Tingley, R., Thompson, M. B., Hartley, S. & Chapple, D. G. Patterns of niche filling and expansion across the invaded ranges of an Australian lizard. Ecography 39, 270–280, https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.01576 (2016).

Grinnell, J. The Niche-Relationships of the California Thrasher. The Auk 3, 427–433 (1917).

Blossey, B. & Notzold, R. Evolution of Increased Competitive Ability in Invasive Nonindigenous Plants: A Hypothesis. The Journal of Ecology 83, https://doi.org/10.2307/2261425 (1995).

Hutchinson, G. Concluding remarks. Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology 22, 415–427 (1957).

Keane, R. Exotic plant invasions and the enemy release hypothesis. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 17, 164–170, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0169-5347(02)02499-0 (2002).

Urban, M. C., Phillips, B. L., Skelly, D. K. & Shine, R. The cane toad’s (Chaunus [Bufo] marinus) increasing ability to invade Australia is revealed by a dynamically updated range model. Proc Biol Sci 274, 1413–1419, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2007.0114 (2007).

Broennimann, O. & Guisan, A. Predicting current and future biological invasions: both native and invaded ranges matter. Biol Lett 4, 585–589, https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2008.0254 (2008).

Beaumont, L. J. et al. Different climatic envelopes among invasive populations may lead to underestimations of current and future biological invasions. Diversity and Distributions 15, 409–420, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1472-4642.2008.00547.x (2009).

Wilson, J. R. U. et al. Residence time and potential range: crucial considerations in modelling plant invasions. Diversity and Distributions 13, 11–22, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1366-9516.2006.00302.x (2007).

Pysek, P. et al. Geographical and taxonomic biases in invasion ecology. Trends Ecol Evol 23, 237–244, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2008.02.002 (2008).

van Wilgen, N. J., Gillespie, M. S., Richardson, D. M. & Measey, J. A taxonomically and geographically constrained information base limits non-native reptile and amphibian risk assessment: a systematic review. PeerJ 6, e5850, https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.5850 (2018).

Bellard, C. & Jeschke, J. M. A spatial mismatch between invader impacts and research publications. Conserv Biol 30, 230–232, https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12611 (2016).

Guisan, A., Petitpierre, B., Broennimann, O., Daehler, C. & Kueffer, C. Unifying niche shift studies: insights from biological invasions. Trends Ecol Evol 29, 260–269, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2014.02.009 (2014).

Broennimann, O. et al. Measuring ecological niche overlap from occurrence and spatial environmental data. Global Ecology and Biogeography 21, 481–497, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1466-8238.2011.00698.x (2012).

Blonder, B., Lamanna, C., Violle, C. & Enquist, B. J. Then-dimensional hypervolume. Global Ecology and Biogeography 23, 595–609, https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12146 (2014).

Blonder, B. et al. New approaches for delineatingn-dimensional hypervolumes. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 9, 305–319, https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210x.12865 (2018).

Warren, D. L., Glor, R. E. & Turelli, M. Environmental niche equivalency versus conservatism: quantitative approaches to niche evolution. Evolution 62, 2868–2883, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1558-5646.2008.00482.x (2008).

Pili, A. N., Sy, E. Y., Diesmos, M. L. L. & Diesmos, A. C. Island Hopping in a Biodiversity Hotspot Archipelago: Reconstructed Invasion History and Updated Status and Distribution of Alien Frogs in the Philippines1. Pacific Science 73, https://doi.org/10.2984/73.3.2 (2019).

Pili, A. N., Supsup, Christian, E., Diesmos, Mae Lowe, L. & Diesmos, Arvin C. In Island invasives: scaling up to meet the challenge (eds. C. R. Veitch, Clout, M. N., Martin, J. C., Russel, J. C., & West, C. J.) 327–347 (IUCN, Dundee, Scotland, 2019).

Kraus, F. Alien reptiles and amphibians: a scientific compendium and analysis. Vol. 4 (Springer Science & Business Media, 2009).

Kraus, F. Impacts from Invasive Reptiles and Amphibians. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 46, 75–97, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-112414-054450 (2015).

Araujo, M. B. & New, M. Ensemble forecasting of species distributions. Trends Ecol Evol 22, 42–47, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2006.09.010 (2007).

HerpWatch Pilipinas, I., Pili, A. N., Diesmos, M. L. L. & Diesmos, A. C. DAYO: Invasive Alien Amphibians in the Philippines. Version 1.4. HerpWatch Pilipinas, Inc. Occurrence dataset accessed. v. 1.0, https://doi.org/10.15468/o24m0j (Date of access: 17/2/2019) (2019).

Gallagher, R. V., Beaumont, L. J., Hughes, L. & Leishman, M. R. Evidence for climatic niche and biome shifts between native and novel ranges in plant species introduced to Australia. Journal of Ecology 98, 790–799, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2745.2010.01677.x (2010).

Simberloff, D. The Role of Propagule Pressure in Biological Invasions. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 40, 81–102, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.110308.120304 (2009).

Soberon, J. & Arroyo-Pena, B. Are fundamental niches larger than the realized? Testing a 50-year-old prediction by Hutchinson. PLoS One 12, e0175138, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0175138 (2017).

Phillips, B. L., Brown, G. P. & Shine, R. Evolutionarily accelerated invasions: the rate of dispersal evolves upwards during the range advance of cane toads. J Evol Biol 23, 2595–2601, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1420-9101.2010.02118.x (2010).

Kolbe, J. J., Kearney, M. & Shine, R. Modeling the consequences of thermal trait variation for the cane toad invasion of Australia. Ecol Appl 20, 2273–2285, https://doi.org/10.1890/09-1973.1 (2010).

Kearney, M. & Porter, W. Mechanistic niche modelling: combining physiological and spatial data to predict species’ ranges. Ecol Lett 12, 334–350, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2008.01277.x (2009).

Pulliam, H. R. On the relationship between niche and distribution. Ecology Letters 3, 349–361, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1461-0248.2000.00143.x (2000).

Scalera, R. et al. Progress toward pathways prioritization in compliance to Aichi Target 9. Report No. UNEP/CBD/SBSTTA/20/1/Rev.1., (Convention on Biological Diversity 2016).

Elith, J. & Graham, C. H. Do they? How do they? WHY do they differ? On finding reasons for differing performances of species distribution models. Ecography 32, 66–77, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0587.2008.05505.x (2009).

Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF). GBIF Occurrence Download. v. doi: 10.15468/dl.hunni9 (Date of access: 17/2/2019) (2019).

Darwin Core Task Group. Darwin Core. Biodiversity Information Standards (TDWG), http://www.tdwg.org/standards/450 (2009).

IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature), Conservation International & NatureServe. Hoplobatrachus rugulosus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. v. 6.1. IUCN, http://www.iucnredlist.org (Date of access: 17/2/2019) (2008).

IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature), Conservation International & NatureServe. Rhinella marina. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. v. 6.1. IUCN, http://www.iucnredlist.org (Date of access: 17/2/2019) (2009).

IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature), Conservation International & NatureServe. Kaloula pulchra. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. v. 6.1. IUCN, http://www.iucnredlist.org (Date of access: 17/2/2019) (2008).

IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) & Conservation International. Hylarana erythraea. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. v. 6.1. IUCN, http://www.iucnredlist.org (Date of access: 17/2/2019) (2014).

Elith, J., Kearney, M. & Phillips, S. The art of modelling range-shifting species. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 1, 330–342, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2041-210x.2010.00036.x (2010).

Boria, R. A., Olson, L. E., Goodman, S. M. & Anderson, R. P. Spatial filtering to reduce sampling bias can improve the performance of ecological niche models. Ecological Modelling 275, 73–77, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2013.12.012 (2014).

Fick, S. E. & Hijmans, R. J. WorldClim 2: new 1-km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. International Journal of Climatology 37, 4302–4315, https://doi.org/10.1002/joc.5086 (2017).

Bennett, A. F. Thermal dependence of locomotor capacity. Am J Physiol 259, R253–258, https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.1990.259.2.R253 (1990).

Rohde, K. Latitudinal Gradients in Species Diversity: The Search for the Primary Cause. Oikos 65, https://doi.org/10.2307/3545569 (1992).

Wells, K. D. The ecology and behavior of amphibians. (University of Chicago Press, 2010).

Caldwell, R. S. & Jones, G. S. Winter Congregations of Plethodon cinereus in Ant Mounds, with Notes on Their Food Habits. American Midland Naturalist 90, https://doi.org/10.2307/2424475 (1973).

Caldwell, R. S. Observations on the winter activity of the red-backed salamander, Plethodon cinereus, in Indiana. Herpetologica 31, 21–22 (1975).

Fraser, D. F. Empirical Evaluation of the Hypothesis of Food Competition in Salamanders of the Genus Plethodon. Ecology 57, 459–471, https://doi.org/10.2307/1936431 (1976).

Alford, R. A. & Richards, S. J. Global Amphibian Declines: A Problem in Applied Ecology. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 30, 133–165, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.30.1.133 (1999).

Araújo, M. B., Thuiller, W. & Pearson, R. G. Climate warming and the decline of amphibians and reptiles in Europe. Journal of Biogeography 33, 1712–1728, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2006.01482.x (2006).

Buckley, L. B. & Jetz, W. Environmental and historical constraints on global patterns of amphibian richness. Proc Biol Sci 274, 1167–1173, https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2006.0436 (2007).

Sodhi, N. S. et al. Measuring the meltdown: drivers of global amphibian extinction and decline. PLoS One 3, e1636, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0001636 (2008).

Austin, M. P. Spatial prediction of species distribution: an interface between ecological theory and statistical modelling. Ecological Modelling 157, 101–118, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-3800(02)00205-3 (2002).

Di Cola, V. et al. ecospat: an R package to support spatial analyses and modeling of species niches and distributions. Ecography 40, 774–787, https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.02671 (2017).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing v. 3.6.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2019).

Olson, D. M. et al. Terrestrial Ecoregions of the World: A New Map of Life on Earth. BioScience 51, 10.1641/0006-3568(2001)051[0933:Teotwa]2.0.Co;2 (2001).

Silverman, B. W. Density estimation for statistics and data analysis. (Routledge, 2018).

Schoener, T. W. Nonsynchronous Spatial Overlap of Lizards in Patchy Habitats. Ecology 51, 408–418, https://doi.org/10.2307/1935376 (1970).

Blonder, B. & Harris, D. J. High Dimensional Geometry and Set Operations Using Kernel Density Estimation, Support Vector Machines, and Convex Hulls. R package. v. 2.0.11 (2018).

Mammola, S. & Leroy, B. Applying species distribution models to caves and other subterranean habitats. Ecography 41, 1194–1208, https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.03464 (2018).

Hastie, T., Tibshirani, R. Generalized additive models. (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1990).

McCullagh, P., Nelder, J. A. Generalized Linear Models. 2 edn, (Chapman & Hall/CRC, 1989).

Friedman, J. H. Multivariate Adaptive Regression Splines. The Annals of Statistics 19, 1–67, https://doi.org/10.1214/aos/1176347963 (1991).

Breiman, L., Friedman, J., Stone, C. J., Olshen, R.A. Classification and regression trees. (CRC press, 1984).

Lek, S. & Guégan, J. F. Artificial neural networks as a tool in ecological modelling, an introduction. Ecological Modelling 120, 65–73, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0304-3800(99)00092-7 (1999).

Breiman, L. Random Forest. Machine Learning 45, 5–32, https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1010933404324 (2001).

Friedman, J. H. Greedy Function Approximation: A Gradient Boosting Machine. The Annals of Statistics 29, 1189–1232 (2001).

Phillips, S. J., Anderson, R. P. & Schapire, R. E. Maximum entropy modeling of species geographic distributions. Ecological Modelling 190, 231–259, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2005.03.026 (2006).

Barbet-Massin, M., Jiguet, F., Albert, C. H. & Thuiller, W. Selecting pseudo-absences for species distribution models: how, where and how many? Methods in Ecology and Evolution 3, 327–338, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2041-210x.2011.00172.x (2012).

Thuiller, W., Lafourcade, B., Engler, R. & Araújo, M. B. BIOMOD - a platform for ensemble forecasting of species distributions. Ecography 32, 369–373, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0587.2008.05742.x (2009).

Thuiller, W., Georges, D., Engler, R. & Breiner, F. biomod2: Species distribution modeling within an ensemble forecasting framework. R Package v. 3.3-7.1 (2016).

Fielding, A. H. & Bell, J. F. A review of methods for the assessment of prediction errors in conservation presence/absence models. Environmental Conservation 24, 38–49, https://doi.org/10.1017/s0376892997000088 (2002).

Allouche, O., Tsoar, A. & Kadmon, R. Assessing the accuracy of species distribution models: prevalence, kappa and the true skill statistic (TSS). Journal of Applied Ecology 43, 1223–1232, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2664.2006.01214.x (2006).

Swets, J. A. Measuring the accuracy of diagnostic systems. Science 240, 1285–1293, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.3287615 (1988).

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to two anonymous reviewers for investing their time and effort in helping improve the quality of the paper. We thank the Ministry for the Environment of the Government of Japan through the ecological monitoring data mobilization grant (BIFA3_26) of the Global Biodiversity Information Facility (GBIF) –Biodiversity Information Fund for Asia (BIFA); the Philippine Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) through their Foreign-assisted Special Projects; and the Biodiversity Management Bureau (BMB) of the DENR through GEF-UNEP Removing Barriers to Invasive Species Management in Production, and Protection Forests in Southeast Asia (FORIS) Project. Richard Thomas B. Pavia, Jr., Carmela P. Española, and Jonathan A. Anticamara for suggesting improvements to the M.Sc. thesis version of this manuscript and Lara Jane Mendoza for copy editing the manuscript. ANP thanks the Science Education Institute (SEI) of the Philippine Department of Science and Technology (DOST) through the Accelerated Science and Technology Human Resource Development Program (ASTHRDP) for the M.Sc. Scholarship, National Geographic Society for the Young Explorers grant (ASIA 57-16), Monash University for the Dean’s Postgraduate Research Scholarship (DPRS) and Dean’s International Postgraduate Research Scholarship (DIPRS), Christian Supsup for sharing his expertise in geographic information systems and ENM during preliminary investigations, and Dr. Wendy Jesse for her guidance in PCA during preliminary investigations. RT was supported by an Australian Research Council DECRA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.N.P. conceived and designed the study; A.N.P., E.Y.S., M.L.D., and A.C.D. gathered the data; A.N.P. and R.T. performed the statistical analysis; A.N.P. and R.T. created the figures; All authors wrote and contributed to the editing of the manuscript and participated in technical discussions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pili, A.N., Tingley, R., Sy, E.Y. et al. Niche shifts and environmental non-equilibrium undermine the usefulness of ecological niche models for invasion risk assessments. Sci Rep 10, 7972 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-64568-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-64568-2

This article is cited by

-