Abstract

Albuminuria is a key biomarker for cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney disease. Our study aimed to describe the prevalence of albuminuria amongst people who inject drugs in London and to test any potential associations with demographic characteristics, past diagnoses, and drug preparation and administration practices. We carried out a cross-sectional survey amongst people who use drugs in London. The main outcome measure was any albuminuria including both microalbuminuria and macroalbuminuria. Three-hundred and sixteen samples were tested by local laboratory services. Our study initially employed point-of-care testing methods but this resulted in a high number of false positives. Our findings suggest the prevalence of albuminuria amongst PWID is twice that of the general population at 19% (95%CI 15.3–24.0%). Risk factors associated with albuminuria were HIV (aOR 4.11 [95% CI 1.37–12.38]); followed by overuse of acidifier for dissolving brown heroin prior to injection (aOR 2.10 [95% CI 1.04–4.22]). Albuminuria is high amongst people who inject drugs compared to the general population suggesting the presence of increased cardiovascular and renal pathologies. This is the first study to demonstrate an association with acidifier overuse. Dehydration may be common amongst this population and may affect the diagnostic accuracy of point-of-care testing for albuminuria.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

People who inject drugs (PWID) may be at risk of serious cardiovascular and kidney diseases, including AA amyloidosis, related to chronic inflammatory conditions and poor overall health. Certain drug injecting practices (e.g. subcutaneous injecting, reuse of injecting equipment) are associated with chronic or recurrent abscesses and other skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs)1. Currently, there are few studies looking at early risk markers of cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney disease among PWID, though there is some evidence to suggest that PWID are at increased risk of developing end-stage renal disease2,3,4,5. Other injecting practices believed to precipitate inflammation relate to the over-use of acidifiers used to dissolve brown heroin which is the predominant type of heroin available in Europe6. It is well established that chronic inflammation is associated with both cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney disease7,8.

Albuminuria is one of the two biochemical markers used to identify the presence of both cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney disease9. The presence of albuminuria is a key risk marker for predicting progression to end-stage renal disease, and for identifying other serious sequelae including AA amyloidosis9. A person with elevated albuminuria but with normal estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) has the same cardiovascular risk as a person with an low eGFR (<60) without albuminuria9,10. Albuminuria has been associated with additional microvascular pathologies (e.g. involving the skin, brain, lungs) which suggests that albuminuria may also be a marker of systemic microvascular disorder11. Albuminuria is associated with cardiovascular risk factors including; overweight/obesity, diabetes, high blood pressure, and tobacco smoking10.

Population-level estimates reveal a high prevalence of albuminuria in the UK. A 2004 study among those aged 40–79 years in Norfolk, UK estimated the prevalence of microalbuminuria as 11.2% (13.9% in women, 8.1% in men) and macroalbuminuria as 0.7% (0.7% in women, 0.8% in men)12. The 2009 and 2010 Health Surveys for England estimated that 8% of adults surveyed had abnormal levels of albumin in their urine (7.9% microalbuminuria, 0.5% macroalbuminuria)10.

This paper aims to describe the prevalence of albuminuria among PWID, and to inform the clinical use and interpretation of albuminuria testing amongst this population.

Methods

We undertook a cross-sectional survey, as part of the UK National Institute for Health Research-funded Care & Prevent study, aimed at assessing the evidence for AA amyloidosis amongst PWID13. We developed a computer-assisted questionnaire to identify patterns of drug use and potential risk factors for SSTIs and AA amyloidosis. The questionnaire was conducted with current or past PWID aged 18 years and over who were recruited in London at eight drug treatment services and a mobile health service working with homeless people (UCLH Find & Treat Service). Participants completed the questionnaire followed by a urine screen for albuminuria. Participants were asked questions relating to: demographics, injecting history, injection practices, HIV and hepatitis C virus (HCV) status, SSTI history, and other conditions associated with albuminuria. Potential confounders were age, sex, and tobacco smoking.

Urine was initially tested using laboratory urinalysis and/or point of care (POC) testing using CLINITEX Microalbumin Reagent Strip (Siemens Healthcare GmbH), however, the POC testing yielded a high number of false positives (See Text Box 1) and was abandoned in favour of laboratory urinalysis. Albumin levels between 2.8 and 29.9 mg/mmol were considered abnormal (i.e. microalbuminuria), and ≥30 mg/mmol were deemed highly abnormal (i.e. macroalbuminuria). Participants with macroalbuminuria were referred to the University College London (UCL) National Amyloidosis Centre at Royal Free Hospital in North London for diagnostic assessment for AA amyloidosis.

Survey data were collected in Open Data Kit (https://opendatakit.org/) and transferred into Stata 15 (StataCorp: College Station, TX) for analysis.

All participants were provided with study information sheets and gave written consent prior to answering the questionnaire and providing a sample for urinalysis. Participants were reimbursed for their time with a £10 gift voucher. All methods were carried out in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. This study has been reported against the STROBE reporting checklist for observational studies14.

Patient and public involvement

The survey was developed in collaboration with the Lambeth and Camden Drug User Forums. Members of the National Amyloidosis Centre Patient Network helped develop the participant information sheets. Groundswell, a local homelessness charity15, provided input to the study as well as peer support16,17 (See GRIPP2 Reporting Checklist Appendix 1).

Sample size

We aimed to collect urine samples from 400 participants based on feasibility (rates of service attendance) and an estimated 5% prevalence of proteinuria (95% CI, 3–7%).

Quantitative variables

The main outcomes of interest were any albuminuria; microalbuminuria (a biomarker for other health outcomes, such as cardiovascular disease) and macroalbuminuria (a biomarker for AA-amyloidosis). Exposures were chosen a priori as plausible factors in the causal chain and were based on the literature, our clinical experience, and our prior research involving PWID. Exposures include: injecting practices, location of injection sites, number of injection sites used, SSTI history, severity of past or current SSTI, housing status, overuse of acidifier (for dissolving drugs prior to injection), and self-reported lifetime diagnoses of health conditions (e.g. necrotising fasciitis, COPD, sepsis, endocarditis). Smoking status was added to the survey following commencement of data collection owing to the unexpectedly high prevalence of microalbuminuria, and is thus only available for 75% of the total sample, and 95% of the subsample of participants for whom we have laboratory results.

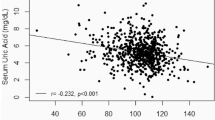

Statistical analysis

Associations between potential risk factors and albuminuria were tested using crude logistic regressions. Bivariate associations found to have a significance of ≤0.1 were introduced into the multivariate logistic model to examine independent associations with albuminuria. We used a 95% confidence interval for the calculation of population point estimates of albuminuria. We further estimated a ratio of the prevalence of albuminuria in our PWID sample to the prevalence in the general population using data from the Health Survey for England 2016, which included urinalysis. We fit a poisson regression model on the combined data with albuminuria as the dependent variable and drug injection as the independent variable, adjusting for age group and sex. We then additionally adjusted for smoking status (current, former, or non-smoker).

Ethics Approval

The study was approved by the NHS Health Research Authority (218143), the NHS Research Ethics Committee (17/LO/0872), and the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Observational Research Ethics Committee (12021–1). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study.

Results

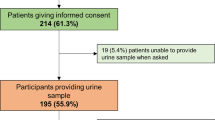

Of the 455 participants who completed the survey, 442 consented to urinalysis. Three-hundred and sixteen laboratory urinalyses were returned. The 139 samples not included in the analysis were either tested using the POC CLINITEX Microalbumin Reagent Strips only (e.g. for services with no laboratory pathway) or they were rejected by the laboratory (e.g. the sample container was damaged). We compared the personal characteristics of those from whom we obtained a sample to those from whom we did not using the Mann–Whitney U test (for age) and Pearson χ-squared and found no significant difference between the two groups (See Appendix 2).

Descriptive data

The majority of the 316 participants were white (73%) and male (75%), both their mean and median age was 46 years old (IQR 39–52). The average age at first injection drug use was 24 years (See Table 1). Of the 316 participants, 169 (54%) reported a diagnosis of HCV, 77 (24%) deep vein thrombosis (DVT), 45 (14%) chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), 27 (9%) kidney disease, and seven (2%) necrotising fasciitis. Seventeen (5%) participants reported receiving an HIV diagnosis (See Table 2).

The majority of participants reported having a history of street homelessness (n = 242, 77%), with 57% (n = 180) currently living in unstable accommodation. The majority reported a typical injecting practice which included injecting one or more times per day (n = 227, 72%), and/or injection into the femoral vein (lifetime: n = 136, 43%, past 12 months: n = 62, 32%) (See Table 3). One-hundred and thirteen (39%) reported over-use of acidifier (defined as more than half a sachet of citric acid or vitamin C6) when preparing a £10 bag of heroin. Three hundred participants provided data on smoking status; 272 (91%) reported current or past smoking.

Outcome data

Of the 316 urinalysis results, sixty-one (19.3% [95% CI 15.3–24.0]) were positive for albuminuria with ≥2.8 mg/mmol albumin/creatinine ratio. Of these, 52 (16% [95% CI 12.8–21.0]) were classified as having microalbuminuria, and nine (3% [95% CI 1.5–5.4]) had macroalbuminuria. Men and women differed slightly but not significantly: 21.2% (95% CI 16.4–26.9) of men and 15% (95% CI 8.6–24.8) of women were found to have albuminuria. The prevalence of albuminuria generally increased with age: 13.6% (95% CI 6.1–27.7) in participants aged ≤35, and 21.4% (95% CI 16.1–27.9) in those aged ≥45, however this was not significant (p > 0.05). The nine participants with macroalbuminuria were referred to the UCL National Amyloidosis Centre and were offered Groundswell peer support (four declined to attend, three attended, and two died before their appointment).

Main results

In a series of crude analyses the following associations were found with albuminuria (See Table 4 for associations): acidifier overuse (OR 1.77, p = 0.061), COPD (OR 2.15, p = 0.033), HCV (OR 1.86, p = 0.037), DVT (OR 1.69, p = 0.090), HIV (OR 3.18, p = 0.025), and injecting in three body sites (OR 2.49 p = 0.079). There was no significant association between SSTIs (OR 0.87, p = 0.643) or groin injecting (OR 1.36, p = 0.282).

Based on these associations we performed logistic regression using listwise deletion of observations with missing smoking status and adjusted for a priori confounders (i.e. age, gender, and current smoking). We found higher odds of having albuminuria amongst those who: reported using more than half a sachet of acidifier per £10 of heroin (aOR 1.71 [95% CI 0.90–3.25]); had been previously diagnosed with COPD (aOR 1.85 [95% CI 0.84–4.06]), HCV (aOR 1.72 [95% CI 0.93–3.20]), HIV (aOR 3.16 [95% CI 1.06–9.41]), and injecting in three body sites (aOR 2.08 [95% CI 0.71–6.06]).

Further adjustment for other covariates suggested that the risk factor with the largest association with albuminuria was HIV (aOR 4.11 [95% CI 1.37–12.38]) followed by over-use of acidifier in injection preparation (aOR 2.10 [95% CI 1.04–4.22]).

In order to determine the age-adjusted prevalence ratio we compared our sample to the Health Survey for England data for 2016. Accounting for smoking status and stratified by age, we excluded the youngest (<25) and oldest (65+) age groups as they included small numbers of observations. The adjusted prevalence ratio suggests that albuminuria is twice as prevalent (1.97 [95% CI 1.49–2.60]) in our population compared to the general population in England.

Discussion

Statement of principal findings

This study sought to determine the prevalence of albuminuria amongst PWID in London. Previous studies have estimated that albuminuria in the general adult population in the UK is less than 10%12,18,19. Our findings suggest prevalence amongst PWID is twice that at 19% (15.3–24.0%). However, the age distribution in our sample differs markedly from that of the general adult population18. Adjusting for current smoking the prevalence ratio decreased to 1.65 (95% CI 1.17–2.31), suggesting that about one-third of the increased prevalence relates to smoking. Within our sample of PWID, overuse of acidifier and HIV were important predictors of albuminuria.

HIV is known to be associated with proteinuric renal lesions20. Additionally, we hypothesise that persistent overuse of acidifier in injection solution is precipitating venous sclerosis (owing to endothelial stress), thus complicating venous access and resulting in multiple venous injection attempts (and possible accidental subcutaneous injecting) and/or transition to intentional subcutaneous injecting21. Subcutaneous injecting introduces substances and/or bacteria directly into tissues which, in turn, causes persistent localised inflammation1. Alternatively, we cannot rule out the possibility that over-use of acidifier is directly causing local or systemic inflammation6. Chronic inflammation is strongly associated with cardiovascular and renal disease of which albuminuria is a biomarker9.

These data suggest that PWID are a high-risk group to develop cardiovascular and renal complications. A recent study of mortality among people who use heroin in South London found 2.8 times the risk of cardiovascular mortality compared to the general population22. If the associations (as observed in the general UK population) between albuminuria and future risk of cardiovascular disease are also true for PWID, one would expect the stroke risk in this population to be increased by 90% relative to a person with no albuminuria23, whilst the absolute risk of cardiovascular mortality increases by about 30% for a doubling of albuminuria24.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

Initially, urine sample testing was carried out using a POC testing machine; however, false positives were identified following confirmatory laboratory testing We believe this to be a result of high levels of dehydration amongst PWID. Our prevalence estimate may have been improved by testing twice (as per NICE guidelines); however, this would have been difficult given our study population9. The Health Survey for England albuminuria data were collected based on the same protocol used for the present study (i.e. a single sample) therefore increasing its comparability with our study population18.

The absence of a significant association between SSTIs and albuminuria was surprising as we anticipated SSTIs would be a key factor in activating the inflammatory cascade. It is possible that our participants underreported past SSTIs or that our sample was underpowered to draw out this association. Our study may also have been underpowered to detect other meaningful predictor variables. Fnally, we cannot rule out the possibility that HIV and excessive use of acidifier may be contributing to a systemic microvascular disorder.

Unanswered questions and future research

Future studies should investigate long-term outcomes of PWID realted to cardiovascular and renal risk, though we appreciate the challenges of following up a difficult to capture population. Future trials should investigate whether cardiovascular and renal disease may be delayed by blood pressure lowering therapy or a poly-pill (i.e. a pill containing a combination of several medications) in those with albuminuria. In addition, studies could explore the reversibility of albuminuria through risk reduction and/or entry into substance use treatment (e.g. opioid agonist therapy). We encourage evaluations of the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of albuminuria screening amongst PWID.

Conclusion

Albuminuria is twice as prevalent among PWID compared to the general population and may identify those with high cardiovascular and renal risk. Clinicians, such as general practitioners, should be aware of the risk and consider albuminuria testing of PWID. Finally, dehydration may be common amongst PWID and may affect the diagnostic accuracy of POC testing for albuminuria. We encourage careful interpretation of albuminuria tests among this population.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

References

Murphy, E. L. et al. Risk Factors for Skin and Soft-Tissue Abscesses among Injection Drug Users: A Case-Control Study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 33, 35–40, https://doi.org/10.1086/320879 (2001).

Scott, J. K., Taylor, D. M. & Dudley, C. R. K. Intravenous drug users who require dialysis: causes of renal failure and outcomes. Clin. Kidney J. 11, 270–274, https://doi.org/10.1093/ckj/sfx090 (2018).

Perneger, T. V., Klag, M. J. & Whelton, P. K. Recreational drug use: a neglected risk factor for end-stage renal disease. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 38, 49–56, https://doi.org/10.1053/ajkd.2001.25181 (2001).

Hileman, C. O. & McComsey, G. A. The Opioid Epidemic: Impact on Inflammation and Cardiovascular Disease Risk in HIV. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep. 16, 381–388, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-019-00463-4 (2019).

Harris, M. et al. Drawing attention to a neglected injecting-related harm: a systematic review of AA amyloidosis among people who inject drugs. Addiction 113, 1790–1801, https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14257 (2018).

Harris, M. et al. Injecting-related health harms and overuse of acidifiers among people who inject heroin and crack cocaine in London: a mixed-methods study. Harm Reduct. J. 16, 60, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-019-0330-6 (2019).

Mihai, S. et al. Inflammation-Related Mechanisms in Chronic Kidney Disease Prediction, Progression, and Outcome. J. Immunol. Res. 2018, 2180373–2180373, https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/2180373 (2018).

Golia, E. et al. Inflammation and cardiovascular disease: from pathogenesis to therapeutic target. Curr. atherosclerosis Rep. 16, 435, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11883-014-0435-z (2014).

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Chronic kidney disease in adults: assessment and management, https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg182/chapter/1-Recommendations (2015).

Fraser, S. D. S. et al. Chronic kidney disease, albuminuria and socioeconomic status in the Health Surveys for England 2009 and 2010. J. Public. Health 36, 577–586, https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdt117 (2013).

Barzilay, J. I. et al. Hospitalization Rates in Older Adults With Albuminuria: The Cardiovascular Health Study. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A, https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glaa020 (2020).

Yuyun, M. F. et al. Microalbuminuria independently predicts all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in a British population: The European Prospective Investigation into Cancer in Norfolk (EPIC-Norfolk) population study. Int. J. Epidemiol. 33, 189–198, https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyh008 (2004).

Harris, M. et al. ‘Care and Prevent’: rationale for investigating skin and soft tissue infections and AA amyloidosis among people who inject drugs in London. Harm Reduction. Journal 15, 23, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-018-0233-y (2018).

Equator Network. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. (University of Oxford, Oxford, 2019).

Groundswell. Groundswell: Out of homelessness, http://groundswell.org.uk (2019).

Hepatitis C Trust. The Hepatitis C Trust, http://www.hepctrust.org.uk (2019).

University College London Hospitals. Find & Treat service, https://www.uclh.nhs.uk/OurServices/ServiceA-Z/HTD/Pages/MXU.aspx] (2019).

Fat, L., Mindell, J. & Roderick, P. Health Survey for England 2016 Kidney and liver disease. (Health and Social Care Information Centre, London, 2017).

Tillin, T., Forouhi, N., McKeigue, P. & Chaturvedi, N. Microalbuminuria and coronary heart disease risk in an ethnically diverse UK population: a prospective cohort study. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 16, 3702–3710, https://doi.org/10.1681/asn.2005060584 (2005).

Fine, D. M., Perazella, M. A., Lucas, G. M. & Atta, M. G. Renal disease in patients with HIV infection: epidemiology, pathogenesis and management. Drugs 68, 963–980, https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-200868070-00006 (2008).

Ciccarone, D. & Harris, M. Fire in the vein: Heroin acidity and its proximal effect on users’ health. Int. J. Drug. Policy 26, 1103–1110, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2015.04.009 (2015).

Lewer, D., Tweed, E. J., Aldridge, R. W. & Morley, K. I. Causes of hospital admission and mortality among 6683 people who use heroin: A cohort study comparing relative and absolute risks. Drug. Alcohol. Dependence 204, 107525, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.06.027 (2019).

Lee, M. et al. Impact of microalbuminuria on incident stroke: a meta-analysis. Stroke 41, 2625–2631, https://doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.581215 (2010).

Hillege, H. L. et al. Urinary albumin excretion predicts cardiovascular and noncardiovascular mortality in general population. Circulation 106, 1777–1782, https://doi.org/10.1161/01.cir.0000031732.78052.81 (2002).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all service users and staff at the following services: Margarete Centre, Lorraine Hewitt House, Better Lives, Response, Find & Treat, Turning Point (Hammersmith, Chelsea & Kensington, and Westminster). Thank you also to Kate Johnstone and Harry Clark from the Camden and Islington research team for their help with recruitment. Additional thanks to Jim Conneely for his ongoing support for the study. Thank you also to Drs Shirley Huchcroft and Louisa Baxter for their advice on the analysis. Finally, we would like to reiterate our gratitude to our research participants who have been exceptionally generous with their time. The study was funded by the UK National Institute for Health Research (CDF-2016–09–014). The funder did not play a role in: the development of the study design; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; or the writing of the manuscript and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. All authors, both internal and external, had full access to the data and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Magdalena Harris is funded by a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), Career Development Fellowship for this research project. This paper presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. Dr Ciccarone acknowledges research funding support from the US National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA037820).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualisation: CM/TW/VH/DC/JD/JG/AS/MH Data curation: TW/RB Formal analysis: CM/TW/DN/DL/DC Funding acquisition: MH Investigation: CM/TW/RB/JD/AS/MH Methodology: CM/DN/DL/JS/VH/DC/MH Project administration: CM/RB/MH Resources: JD/JG/MH Software: TW/DL Supervision: DN/RB/MH Writing-original draft: CM/TW/DN/DL/JS/VH/DC/JD/JG/AS/MH Writing-review & editing: CM/TW/DN/DL/MH.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Dr. McGowan reports personal fees from European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) outside the submitted work. Dr. Nitsch reports other grants from Glaxo Smith Kline, outside the submitted work. Dr. Scott reports other from Turning Point, other from Cognisant Research, non-financial support from Academy of Medical Sciences, grants from Medical Research Council, grants from Pharmacy Research UK, outside the submitted work. Dr. Ciccarone reports grants from the US National Institutes of Heath, National Institute on Drug Abuse, during the conduct of the study; personal fees from Malinckrodt, personal fees from Nektar Therapeutics, personal fees from Celero Systems, personal fees from American Association for the Advancement of Science, outside the submitted work. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Appendices

APPENDIX 1: GRIPP2 Short Form

Section and topic | Item | Reported on page No |

|---|---|---|

1: Aim | Report the aim of PPI in the study | 3 |

2: Methods | Provide a clear description of the methods used for PPI in the study | 3 |

3: Study results | Outcomes—Report the results of PPI in the study, including both positive and negative outcomes | 5 |

4: Discussion and conclusions | Outcomes—Comment on the extent to which PPI influenced the study overall. Describe positive and negative effects. | n/a |

5: Reflections/critical perspective | Comment critically on the study, reflecting on the things that went well and those that did not, so others can learn from this experience | n/a |

APPENDIX 2: Table comparing demographics for those with and without an ACR result

ACR result | No ACR result | Pearson’s chi squared | Mann Whitney U | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

N = 316 | % | N = 139 | % | χ2 (df) | P value | z | P value | |

Age | 1.3 | 0.194 | ||||||

<35 | 44 | 13.9 | 21 | 15.1 | ||||

35–44 | 85 | 26.9 | 45 | 32.4 | ||||

45–54 | 137 | 43.4 | 57 | 41 | ||||

>55 | 50 | 15.8 | 16 | 11.5 | ||||

Gender | 0.04 (1) | 0.846 | ||||||

Male | 236 | 74.7 | 105 | 75.5 | ||||

Female | 80 | 25.3 | 34 | 24.5 | ||||

Stability of housing in previous 12 months | 0.07 (1) | 0.794 | ||||||

Stable (own place, rented) | 136 | 43 | 58 | 41.7 | ||||

Unstable (other people’s places, street homeless, hostel dwelling) | 180 | 57 | 81 | 58.3 | ||||

Ever been street homeless | 242 | 76.6 | 113 | 81.3 | 1.25 (1) | 0.263 | ||

Ethnicity | 4.00 (4) | 0.407 | ||||||

White or White British | 230 | 72.8 | 106 | 76.3 | ||||

African, Caribbean or Black British | 39 | 12.3 | 11 | 7.9 | ||||

Asian or Asian British | 7 | 2.2 | 5 | 3.6 | ||||

Mixed ethnicity | 21 | 6.7 | 6 | 4.3 | ||||

Other | 19 | 6 | 11 | 7.9 | ||||

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

McGowan, C.R., Wright, T., Nitsch, D. et al. High prevalence of albuminuria amongst people who inject drugs: A cross-sectional study. Sci Rep 10, 7059 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-63748-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-63748-4

This article is cited by

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.