Abstract

Direct quantitative measurements of nanoscale dynamical processes associated with structural relaxation and crystallization near the glass transition are a major experimental challenge. These type of processes have been primarily treated as macroscopic phenomena within the framework of phenomenological models and bulk experiments. Here, we report x-ray photon correlation spectroscopy measurements of dynamics at the crystal-melt interface during the radiation induced formation of Se nano-crystallites in pure Se and in binary AsSe4 glass-forming liquids near their glass transition temperature. We observe a heterogeneous dynamical behaviour where the intensity correlation functions g2(q, t) exhibits either a compressed or a stretched exponential decay, depending on the size of the Se nano-crystallites. The corresponding relaxation timescale for the AsSe4 liquid increases as the temperature is raised, which can be attributed to changes in the chemical composition of the melt at the crystal-melt interface with the growth of the Se nano-crystallites.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The structural relaxation during annealing near the glass transition region controls the properties and technological utility of glasses and/or glass-ceramics1,2,3,4. For example, glass products retain thermal stress caused by quenching, which decreases the strength and durability of the product and needs to be removed after forming via annealing5. This stress removal proceeds with structural relaxations through processes that are closely related to diffusion and viscous flow, with similar activation energy, at temperatures close to the glass transition. On the other hand, for glass-ceramics processing, the kinetics of nucleation and growth of crystals is controlled by the diffusion of atoms or larger structural units from the supercooled liquid to the crystal-liquid interface6,7,8. The standard kinetic models treat crystallization of a liquid as a macroscopic phenomenon and the applicability of these models is often hampered by the lack of a direct microscopic understanding of the atomic scale processes that accompany crystallization9,10,11. For example, these models use viscosity or diffusivity values for the bulk supercooled liquid, instead of the “local” microscopic transport property at the crystal-liquid interface, which is more relevant, albeit its experimental measurement would be rather difficult, if not impossible. Whether the transport or the relaxational timescale at the crystal-liquid interface can be treated the same as that of the bulk liquid is a key question that is still awaiting direct experimental confirmation.

X-ray photon correlation spectroscopy (XPCS) is a powerful experimental technique that offers the length scale and timescale resolution appropriate for the investigation of such atomic dynamics at the crystal-liquid interface. However, it has recently been shown that atomic dynamics can also be induced in non-metallic glassy systems by the incident x-ray beam, as it simultaneously pumps and probes the fluctuation dynamics12. Specifically, highly brilliant and coherent x-rays produced at third generation storage rings or free electron lasers can induce atomic movement, possibly through the process of radiolysis resulting in diffusion and long range rearrangement of atoms13.

In this article, we report the results of x-ray beam induced structural rearrangement leading to crystallization in a supercooled glass-forming liquid of pure Se and AsSe4 using XPCS. This technique allows us to capture coherent speckle patterns arising from fluctuations and inhomogeneities associated with the beam induced crystallization of supercooled glass-forming liquids close to their glass transition temperature Tg. The intensity correlation function, which is related to the dynamical structure factor, exhibited either compressed or stretched exponential decay behaviour depending upon the size of the nano-crystallites. For crystallites larger than 70 nm, a compressed exponential behaviour was observed, while for smaller crystallites in the size range of 35–50 nm, a stretched exponential behaviour was observed, which is a hallmark of relaxation dynamics in supercooled glass-forming liquids as Tg is approached from above14. We observed an anomalous increase in the fluctuation timescale at the crystal-liquid interface as the temperature is increased for AsSe4, which likely resulted from a change in the local viscosity at the interface, due to local compositional changes. The results of the present study thus highlight the beam induced nanoscale nucleation and growth dynamics and how such dynamics are affected by crystallite size, in highly viscous supercooled glass-forming liquids.

Results

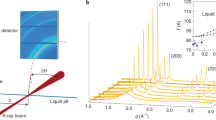

X-ray scattering intensity as a function of q for pure Se and AsSe4 at room temperature is plotted in Fig. 1. For both samples, the key features as well the location of first maximum (principal peak) of the static structure factor, Q0 = 1.8 Å−1 for Se and Q0 = 2.2 Å−1 for AsSe4, agree with the literature values15,16,17. The coherent x-ray beam was tuned to the principal peak in symmetric Bragg geometry. X-ray beam induced crystallization of trigonal selenium was observed for both Se and AsSe4 samples as shown in Fig. 2. It may be noted here that these glasses do not display any detectable crystallization in the absence of radiation, for the same thermal treatments. Furthermore, the beam induced crystallization was also observed during XPCS measurements performed at a different x-ray energy, 7.35 keV, lower than Se edge. Similar evolution of time constant and correlation function was observed as shown in Supplementary Fig. S2, indicating that the crystallization is independent of x-ray energy.

Polycrystalline diffraction rings observed from Se nano-crystallites in supercooled Se and AsSe4 liquid: Spotty polycrystalline rings observed for (a) Se sample at 38 °C, (b) and (c) AsSe4 samle at 89 °C, (d) compares the intensity of the (001) polycrystalline ring for a line cut along Qz for Se sample as a function temperature, and (e) compares the intensity of the (101) polycrystalline ring for a line cut along Qz for AsSe4 sample as a function of temperature.

Fig. 2(a)–(c) presents the polycrystalline rings observed near the principal peak for both Se and AsSe4 sample at Q = 1.61 Å−1 and 2.06 Å−1. Fig. 2(a) is measured at T = 38 °C, while Fig. 2(b),(c) are measured at T = 89 °C. Qz represents the reciprocal vector parallel to the scattering plane and perpendicular to sample surface, while Qx represents the reciprocal vector perpendicular to the scattering plane. Fig. 2(d),(e) depict the line cut through the polycrystalline ring along Qz for Se at 32 °C, 34 °C, 36 °C and 38 °C and for AsSe4 at 27 °C, 84 °C, 87 °C and 89 °C, clearly demonstrating that the polycrystalline rings are absent near room temperature. This result suggests that the atomic motion associated with X-ray beam induced crystallization is a thermally activated process. The polycrystalline diffraction ring observed at the two different q-values correspond to the reflections from (001) and (101) lattice planes of Se18, indicating the formation of Se crystallites near Tg in both Se and AsSe4 samples. The calculated lattice parameters of a = 0.446 nm and c = 0.499 nm, agree well with the literature values reported for trigonal Se6. The spotty polycrystalline ring observed for Bragg reflections in both samples shows that the distribution of Se crystallites is not completely random and points towards the presence of preferred orientation. The Se crystallite sizes were estimated from the diffraction line widths using the Scherrer equation (see supplementary section 3 for details). A larger Se crystallite size in the range of 80–175 nm for Se sample and 70–105 nm for AsSe4 sample was obtained for the preferred orientation (higher intensity spots on the polycrystalline ring), irrespective of the temperature of measurements. These will be referred to as “large” crystallites in the subsequent discussion. On the other hand, for the random orientations (lower intensity regions), a Se crystallite size of ~37 nm was obtained at 32 °C, which increased to ~42 nm at 38 °C for Se sample and a Se crystallite size of ~35 nm was obtained at 84 °C, which increased to ~50 nm at 89 °C for AsSe4 sample. These will be referred to as “small” crystallites. We note that the speckles overlaying the diffraction peak in Fig. 2(d),(e), are a direct result of the disorder present in the sample and the degree of the coherence of the x-ray beam. The underlying dynamics in the sample near Tg manifest itself as the fluctuations of this speckle pattern.

In order to investigate these fluctuations, we measured the evolution of the speckle pattern as a function of time near Tg. Fig. S3 in supplementary info show intensity vs. time “waterfall” plots or kymographs for the measured intensity. In order to quantitatively understand the evolution of small and large crystallites as a function of time, the intensity-intensity autocorrelation function g2(q,t) was calculated from the time-dependent speckle measurements using the relation:

where I(q,t) and I(q, t+τ) are intensities of a given pixel separated in time by τ and <> denotes and ensemble average performed over all equivalent times tau and all equivalent pixels of the regions of interest considered here19,20. For the large Se crystallites, in both Se and AsSe4 samples, the g2(q,t) was calculated by averaging speckles in the high intensity region of the (001) or (101) polycrystalline ring only during the time window where the large crystallites are aligned to the Bragg condition. This procedure allowed us to remove any artifacts due to the sudden variation of intensity associated with the appearanceor disappearance of large crystallite in the XPCS scan. Detailed description of g2(q,t) calculation for large Se crystallites is provided in supplementary information section 5. The g2(q,t) for small crystallites was calculated by averaging speckles in lower intensity region of the (001) or (101) polycrystalline ring. The autocorrelation function calculated from the intensities is related to the intermediate scattering function (ISF), |F(q,t)|2, and can be fitted with a stretched exponential as given in Eq. (2).

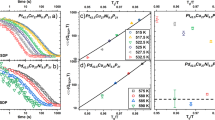

Here A is the speckle contrast, τ is the decay constant and β is the stretching exponent. Fig. 3 shows the temporal evolution of ISF for both Se and AsSe4 samples for temperatures ranging from 32 °C to 38 °C and 84 °C to 91 °C, respectively. Here we note that the ISF value of 1 represents fully correlated system while 0 represents complete de-correlation. While q-dependence due to variation in lengthscales has been observed in similar systems21,22, no significant q-dependence was observed here possibly due to the fact that the lengthscales near the two Bragg peaks represent similar d-spacing (0.1962 nm for (001) and 0.1543 nm for (101) Se Bragg peak). Thus q-dependence was omitted from the g2 and the ISF calculations. We also note that the ISF calculations for diffuse scattering near Bragg peak showed similar results and behaviour, albeit lower signal noise to ratio due to lower intensity. Furthermore, due to low speckle intensity resulting in small signal to noise ratio as well as observation of beam induced crystallization, structural relaxation dynamics of the bulk liquid near Tg could not be detected. No aging behaviour was observed as shown by two-time correlation plots and time-resolved measurements in Figs. S5–S7 of supplementary information

Evolution of ISF as a function of temperature: Experimental ISF data (symbols) and corresponding fits (lines) using Eq. 2 for (a,b) Se sample, (c,d) AsSe4 sample. ISF for large crystallites was calculated by averaging speckles in high intensity region of the polycrystalline rings, only during the time window where large crystallites are aligned to Bragg condition, and for small crystallites was calculated by averaging speckles in lower intensity region of the polycrystalline rings. For the large crystallites, compressed exponential is observed while for the small crystallites, stretched exponential is observed. The fits are based on Eqs. 1 and 2 as described in the text.

Fig. 4 shows the values obtained for τ and β as a function of temperature for both samples. The error bars were calculated using the uncertainty in counting statistics for different Qx regions. Significant temperature dependence of the fluctuation timescale was observed for both samples. For Se sample, a slight decrease in τ is observed for both large and small crystallites on increasing the temperature from 32 °C to 38 °C as shown in Fig. 4(a). This decrease in time constant is consistent with decrease in viscosity of a liquid resulting in higher fluctuations with increasing temperature. However, surprisingly, for AsSe4 sample, an opposite behaviour i.e. an increase in τ is observed for both large and small crystallites on increasing the temperature from 84 °C to 91 °C as shown in Fig. 4(c). The rise in τ is particularly dramatic for the small crystallites, where the timescale increases by nearly an order of magnitude over the measured temperature range. This increase in τ i.e. slowing down of fluctuations as a function of temperature is surprising and counterintuitive as the viscosity of a liquid is expected to decrease with increasing temperature23. The exponent β calculated for the large and small crystallites is shown in Fig. 4(b),(d). We find the exponent to be ~1.5 for the large crystallites, manifested by the compressed shape of ISF in Fig. 3(a),(c). For small crystallites, β ~ 0.5 is observed as shown by the stretched shape of the ISF in Fig. 3(b),(d). A compressed exponential with β > 1 is indicative of a “jammed” system where local displacements create long-range spatial and temporal inhomogeneities24,25,26,27,28, while a stretched exponential with β < 1 is the hallmark of the dynamics of highly viscous liquids near Tg, that corresponds to hierarchical dynamics with caging and escaping of groups of atoms/molecules via cooperative motion29,30,31.

Discussion

For both samples, decay constant (τ) and exponent (β) are plotted in Fig. 4 and mean relaxation time are calculated from decay constant (see supplementary information section 7 for additional details). For small and large crystallites, decay constant of 1830 ± 50 s and 1130 ± 50 s was observed for Se sample at 32 °C, resulting in mean relaxation timescale of 5340 ± 50 s and 1020 ± 50 s. Recent rheological studies have indicated that the viscous flow is controlled by the Se-Se bond scission/renewal process with a characteristic timescale on the order of ~ 6310 s at 32 °C32. Calculated mean relaxation timescales for 32 °C as well as other temperatures (see Table S1 of supplementary information) are thus within the range of characteristic rheological timescales. For AsSe4 sample, a decay constant of 310 ± 50 s and 650 ± 150 s was observed at 84 °C resulting in mean relaxation timescale of 470 ± 50 s and 590 ± 150 s, for small and large crystallites respectively. The calculated mean relaxation timescale at 84 °C is consistent with the shear relaxation timescale of ~440 s, as obtained from the simple Maxwell model \({\tau }_{a}=\eta /{G}_{\infty }\), using \({G}_{\infty }\) of 5 GPa and η = 1000 GPa.s at 84 °C23. Here \({\tau }_{a}\) denotes the characteristic timescale for shear or α-relaxation, η is the viscosity for a given temperature and \({G}_{\infty }\) is the instantaneous (elastic) shear modulus33. Thus, the shear relaxation timescales are within the range of the calculated mean relaxation time from XPCS data for Se sample at all temperatures and AsSe4 sample at 84 °C, indicating that the dynamics at the crystal-liquid interface during the Se crystallization process is mediated via viscous flow of the supercooled liquid phase7. Here we note that for higher temperatures a significant deviation between the two timescales is observed for AsSe4 sample which will be addressed below.

In addition to crystal-liquid interfacial dynamics, another possible reason which could influence the observed dynamics is the motion of the crystallites in supercooled liquid surrounding the crystallites. However, this motion of crystallites is expected to increase at higher temperatures due to lowering of viscosity, which is inconsistent with the observation of slower decay constant (τ) at higher temperature for AsSe4 samples. Additionally, as discussed above, two different types of behaviour are observed based on size of crystallites for both Se and AsSe4 samples. The correlation function (g2) has a compressed shape for larger crystallites and stretched exponential shape for smaller crystallite as shown in Figs. 3 and 4. The two crystallite sizes are fairly close and thus, such a drastic change cannot be explained purely due to size-dependent motion of the crystallites in the super cooled liquid. Hence, for these Se nano-crystallites, the crystal-melt interfacial dynamics could play a critical role in crystallization and the fluctuations observed in the XPCS experiment could be due to atomic motions at the crystal-liquid interface, which are determined by the characteristic shear relaxation timescale of the liquid.

The slowdown of the fluctuation timescale and deviation from shear relaxation timescale at higher temperatures for AsSe4 can then be due to a change in the local chemical composition at the crystal-liquid interface. As the growth of the Se nano-crystallites proceeds, the Se content must get depleted at the crystal-liquid interface and the liquid in the surrounding region must get richer in As content. Higher As-content in the liquid results in higher viscosity and glass transition temperature23, consistent with the observed slowing down of fluctuation timescales. Based on the calculated mean relaxation timescale ~7000 s at 89 °C, we can estimate the viscosity for the higher As-content liquid using the Maxwell model to be η = 2.03 ×1013 Pa.s, indicating an increase in As content by ~5–7%. The fact that this slowdown is not observed in Se samples, emphasizes the role played by local chemical composition in determining the dynamical processes. On the other hand, for the large crystallites, the calculated mean relaxation timescales are: 590 ± 150 s at 84 °C and 1600 ± 300 s at 91 °C. Thus, the rate of increase in timescale with temperature is lower for the large crystallites and is consistent with the lack of the size dependence of these crystallites on temperature, as discussed above.

The drastic variation in the exponent (β) of the ISF for small and large crystallite is very surprising and point towards a difference in the mechanism of the crystallization process. As noted earlier, a stretched exponential decay of the ISF is typical of relaxation processes in glasses and supercooled liquids near Tg29,30,31. The observation of a stretched exponential decay for small crystallites could indicate that the fluctuations observed for the Se nano-crystallites at their early growth stage occur at the crystallite/liquid interface which mediates the crystallization process. On the other hand, the compressed exponent observed for the large crystallites points towards a second mechanism. Compressed exponential behaviour has been observed in sputter deposition of amorphous thin films34 and in crystallization of metallic glasses35. This behaviour has been related to the nonlinearities in Kardar-Parisi-Zhang (KPZ) model of interfacial growth processes and scaling behaviour due to side-ways or lateral growth36,37. Screw dislocation assisted growth has been observed for Se crystallites, where the growth of the crystal results in the development of a spiral growth pattern or a screw dislocation and corresponds to lateral crystal growth6. The observation of a compressed exponential decay for the large crystallites may thus be indicative of such a situation where lateral growth becomes important and needs to be taken into account.

Conclusion

We have presented XPCS measurements in chalcogenide glasses where x-ray beam induced crystallization was observed, providing us a unique opportunity to investigate the crystal-melt interface dynamics in supercooled Se and AsSe4 liquid near Tg. An anomalous increase was observed in the fluctuation timescale at the crystal-liquid interface as the temperature is increased for AsSe4, which likely resulted from a change in the local viscosity at the interface, due to local compositional changes. In comparison, no slowdown was observed in Se samples and calculated relaxation timescales were within the range of rheological timescales, emphasizing the role played by local chemical composition in determining the dynamical processes during crystallization. Additionally, for large crystallites, a compressed exponential behaviour was observed, while for small crystallites, a stretched exponential behaviour was observed. This could be potentially related to the fact that for small crystallites the glassy dynamics occurring at the crystallite/liquid interface is dominant, while for large crystallites non-linear effects due to lateral growth need to be considered.

Methods

Samples

Se and AsSe4 glasses were synthesized from constituent elements (≥99.995% purity, metals basis) using the conventional melt-quench method. Elemental Se and As-Se mixture were melted at 400 °C and 650 °C, respectively, in evacuated (10−6 Torr) and flame sealed fused silica ampoules for 24 h in a rocking furnace. The melts were subsequently quenched by dipping the ampoule in water and the resulting glasses was annealed for 1 h at the nominal Tg. Differential scanning calorimetry scan of this glass yields Tg corresponding to the onset temperature for glass transition to be ~35 °C for Se and ~88 °C for AsSe4. The glass samples were characterized prior to synchrotron studies by powder X-ray diffraction to ensure the absence of any crystallinity, and by Raman spectroscopy to ensure structural consistency with the literature reports.

XPCS measurements

XPCS experiments were conducted at the Coherent Hard X-ray (CHX) beamline 11-ID at the National Synchrotron Light Source II (NSLS-II), Brookhaven National Laboratory. Disk-shaped samples (5 mm diameter, 1 mm thick) of Se and AsSe4 glass with polished flat surfaces were utilized for XPCS studies. Samples were heated on a hot plate inside a vacuum chamber (10−5 torr). The x-ray energy utilized was 12.8 keV, which is above the K-absorption edge of Se (12.658 keV). A coherent beam size of 3 µm was achieved by collimation with a set of 1D Be Compound Refractive Lenses and focused with a set of crossed Si kinoform lenses in front of the sample. The scattered beam was recorded with an area detector located 150 cm away from the sample with a 75 µm × 75 µm pixel size. When coherent x-rays scatter from the static or dynamic disorder present in the supercooled liquid sample, they acquire phase difference dependent upon the disorder and undergo constructive/destructive interference resulting in speckle patterns at the detector. This speckle pattern measured in k-space is a fingerprint of the sample structure in real-space. Moreover, if parts of the sample fluctuate in time, the observed speckle pattern will also fluctuate due to variations of the phase differences between scattered waves. These characteristic speckle patterns were recorded as a function of time, over a period of ~2 hours, at room temperature and at temperatures near Tg. At each temperature, the sample was equilibrated for 30 minutes to ensure stabilization of the target temperature prior to collecting XPCS data for 2 hours. The temperature of the aluminium hot surface over which the sample is glued using a thermal conductive Silver paste is measured with a PT100 platinum resistance thermometer and controlled with a Lakeshore temperature controller. Additional information regarding thermal stability of XPCS setup is provided in supplementary section 1.

Data availability

Data used and analysed in the study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Angell, C. A. The old problems of glass and the glass transition, and the many new twists. PNAS 92, 6675–6682 (1995).

Ediger, M. D., Angell, C. A. & Nagel, S. R. Supercooled liquids and glasses. J. Phys. Chem. 100, 13200 (1996).

Debenedetti, P. G. & Stillinger, F. H. Supercooled liquids and the glass transition. Nature 410, 259–267 (2001).

Wang, J. Glass viscosity and structural relaxation by parallel plate rheometry using a thermo-mechanical analyser. Mat. Lett. 31, 99–103 (1997).

Uhlmann, D. R. & Kreidl, N. J. Glass: Science and Technology, Vol. 5: Elasticity and Strength in Glasses. (Academic Press, 1980).

Málek, J., Barták, J. & Shánělová, J. Spherulitic Crystal growth velocity in selenium supercooled liquid. Cryst. Growth Des. 16, 5811–5821 (2016).

Barták, J., Martinková, S. & Málek, J. Cryst. crystal growth kinetics in Se–Te bulk glasses. Cryst. Growth Des. 15, 4287–4295 (2015).

Ryschenkow, G. & Faivre, G. Bulk crystallization of liquid selenium primary nucleation, growth kinetics and modes of crystallization. J. Cryst. Growth 87, 221–235 (1988).

Markov, I. V. Crystal growth for beginners: fundamentals of nucleation, crystal growth and epitaxy. (World Scientific Publishing, 2003).

Stillinger, F. H. & Debenedetti, P. G. Glass transition thermodynamics and kinetics. Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 4, 263–285 (2013).

Tropin, T. V., Schmelzer, J. W. & Aksenov, V. L. Modern aspects of the kinetic theory of glass transition. Physics-Uspekhi 59, 42–66 (2016).

Ruta, B. et al. Hard X-rays as pump and probe of atomic motion in oxide glasses. Sci. Rep. 7, 3962 (2017).

Pintori, G., Baldi, G., Ruta, B. & Monaco, G. Relaxation dynamics induced in glasses by absorption of hard x-ray photons. Phys. Rev. B. 99, 224206 (2019).

Phillips, J. C. Stretched exponential relaxation in molecular and electronic glasses. Rep. Prog. Phys. 59, 1133–1207 (1996).

Alagesan, V. & Venugopal, S. Green synthesis of selenium nanoparticle using leaves extract of withania somnifera and its biological applications and photocatalytic activities. BioNanoScience 9, 105–116 (2019).

Ye, F. & Lu, K. Pressure effect on polymorphous crystallization kinetics in amorphous selenium. Act. Mat. 46, 5965–5971 (1998).

Leadbetter, A. J. & Apling, A. J. Diffraction studies of glass structure: (V). the structure of some arsenic chalcogenide glasses. J. Non. Cryst. Solids 15, 250–268 (1974).

Guo, X., Fang, L. & Tan, Y. Solution-phase hierarchical self-organization of ultralong Se nanowires into diverse macroarchitectures and their enhanced field emission. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 17, 2794–2803 (2015).

Mochrie, S. G. J. et al. Dynamics of block copolymer micelles revealed by X-Ray intensity fluctuation spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 1275–1278 (1997).

Thurn-Albrecht, T. et al. Photon correlation spectroscopy of colloidal palladium using a coherent X-Ray beam. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 5437–5440 (1996).

Ruta, B. et al. Silica nanoparticles as tracers of the gelation dynamics of a natural biopolymer physical gel. Soft Matter 10, 1447–4554 (2014).

de Melo Marques, F. A. et al. Structural and microscopic relaxations in a colloidal glass. Soft Matter 11, 466–471 (2015).

Bernatz, K. M., Echeverría, I., Simon, S. L. & Plazek, D. J. Characterization of the molecular structure of amorphous selenium using recoverable creep compliance measurements. J. Non. Cryst. Solids. 307, 790–801 (2002).

Cipelletti, L., Manley, S., Ball, R. C. & Weitz, D. A. Universal aging features in the restructuring of fractal colloidal gels. Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 2275–2278 (2000).

Falus, P., Borthwick, M. A., Narayanan, S., Sandy, A. R. & Mochrie, S. G. J. Crossover from stretched to compressed exponential relaxations in a polymer-based sponge phase. Phys. Rev. Lett. 97, 066102 (2006).

Nagamanasa, K. H., Gokhale, S., Ganapathy, R. & Sood, A. K. Confined glassy dynamics at grain boundaries in colloidal crystals. PNAS 108, 11323 (2011).

Wang, Z., Wang, F., Peng, Y., Zheng, Z. & Han, Y. Imaging the homogeneous nucleation during the melting of superheated colloidal crystals. Science 338, 87–90 (2012).

Ramsteiner, I. B., Weitz, D. A. & Spaepen, F. Stiffness of the crystal-liquid interface in a hard-sphere colloidal system measured from capillary fluctuations. Phys. Rev. E. 82, 041603 (2010).

Ruta, B. et al. Revealing the fast-atomic motion of network glasses. Nature Communications 5, 3939 (2014).

Angelini, R. et al. Dichotomic aging behaviour in a colloidal glass. Soft Matter 9, 10955 (2013).

Fluerasu, A., Moussaïd, A., Madsen, A. & Schofield, A. Slow dynamics and aging in colloidal gels studied by x-ray photon correlation spectroscopy. Phys. Rev. E. 76, 010401(R) (2007).

Zhu, W., Aitken, B. G. & Sen, S. Observation of a dynamical crossover in the shear relaxation processes in supercooled selenium near the glass transition. J. Chemical Physics 150, 094502 (2019).

Maxwell, J. C. On the dynamical theory of gases. Proc. Roy. Soc. London 15, 49–88 (1867).

Rainville, M. G. et al. Co-GISAXS technique for investigating surface growth dynamics. Phys. Rev. B. 92, 214102 (2015).

Leitner, M., Sepiol, B., Stadler, L. & Pfau, B. Time-resolved study of the crystallization dynamics in a metallic glass. Phys. Rev. B. 86, 064202 (2012).

Kardar, M., Parisi, G. & Zhang, Y. C. Dynamic scaling of growing interfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 56, 889–892 (1986).

Mokhtarzadeh, M. & Ludwig, K. F. Jr. Simulations of Co‐GISAXS during kinetic roughening of growth surfaces. J. Synchrotron Rad. 24, 1187–1194 (2017).

Acknowledgements

J. L., R.J., C.K. and R.K. acknowledges the support by University of California Davis for this research. S.S. and W.Z. were supported by a grant from the National Science Foundation (DMR 1855176). This research used resources from the 11-ID Coherent Hard X-Ray Scattering (CHX) beam line of the National Synchrotron Light Source II, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Brookhaven National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-SC0012704. We would also like to acknowledge Eric Dufresne for help with XPCS measurements at different x-ray energy. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L., R.K. and S.S. planned the research project including samples and experimental design. W.Z. fabricated the glass samples. J.L. R.J., C.K., A.F., Y.Z. and R.K. participated in the XPCS experiments at NSLS-II. J.L. performed the data analysis with feedback from R.K., S.S., A.F. and Y.Z. J.L. wrote the manuscript with significant contributions from from R.K. and S.S. All co-authors discussed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, J., Jangid, R., Zhu, W. et al. Dynamics at the crystal-melt interface in a supercooled chalcogenide liquid near the glass transition. Sci Rep 10, 5881 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-62783-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-62783-5

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.