Abstract

Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) is an important staple food worldwide. However, its growth has been heavily suppressed by salt stress. The molecular mechanisms of salt tolerance in potato remain unclear. It has been shown that the tetraploid potato Longshu No. 5 is a salt-tolerant genotype. Therefore, in this study we conducted research to identify salt stress response genes in Longshu No. 5 using a NaCl treatment and time-course RNA sequencing. The total number of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in response to salt stress was 5508. Based on Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) analysis, it was found that DEGs were significantly enriched in the categories of nucleic acid binding, transporter activity, ion or molecule transport, ion binding, kinase activity and oxidative phosphorylation. Particularly, the significant differential expression of encoding ion transport signaling genes suggests that this signaling pathway plays a vital role in salt stress response in potato. Finally, the DEGs in the salt response pathway were verified by Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR). These results provide valuable information on the salt tolerance of molecular mechanisms in potatoes, and establish a basis for breeding salt-tolerant cultivars.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Salt is a major abiotic factor affecting plant growth and secondary metabolism1. Soil salinization has become a global problem with about 8 × 108 hectares of soil worldwide threatened by salinization2. Salinity interferes with plant growth as it leads to physiological drought and ion toxicity3. In addition, other secondary stresses, such as oxidative damage, can occur in plants subjected to high NaCl concentrations1. With the increase of salinization, it is a tough challenge to increase grain output and achieve food security.

Potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) is an extremely important food staple worldwide due to its versatility and nutritional value. However, potato is quite sensitive to salt stress, which is one of the most important factors limiting its cultivation4 and which can lead to serious declines in yield5,6. Therefore, there is a great need to improve the salt tolerance of potato and breed salt-tolerant varieties. What’s more, illuminating the molecular mechanisms underlying salt tolerance and identifying the related genes of tolerant plants may contribute to further understanding the functions of these unique genes.

Previous studies have revealed mechanisms underlying salt stress tolerance in plants. Plant membrane receptors sense extracellular salt stress stimuli, and then these stimuli signals are translated into intracellular signals through the generation of second messengers such as calcium, reactive oxygen species (ROS) and inositol phosphates. These second messengers then activate transcription factors (TFs) or protein kinases (PKs), inducing specific genes to be differentially expressed7. These signal cascades result in the expression of multiple stress-responsive genes, the products of which can directly or indirectly confer stress tolerance8. The complex gene expression cascades activated during the response to salt stress involve signaling pathways related to Na+ efflux and Na+ localization9, which are regulated by calcium-activated 14-3-3 proteins that act as molecular switches10. In addition, the mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) and SOS (salt overly sensitive) can jointly participate in Na+ efflux and Na+ localization signaling pathways to promote the maintenance of ion equilibrium9. Therefore, receptor proteins, Ca signals, TFs and PKs play pivotal roles in salt stress responses.

The SOS signaling pathway is the most widely studied salt tolerance pathway in plants at present11. The regulation of salt stress response by the SOS pathway mainly involves five core components, the calcineurin B-like protein 1/10 (SCaBP5/8)/CBL-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase 24 (SOS2) complex, the CBL-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase 5 (PKS5)/14-3-3 protein complex, SOS1 (a plasma membrane Na+/H+ antiporter), AHX (a vacuolar Na+/H+ exchanger) and ATPase12. Under normal conditions, PKS5 or PKS24 phosphorylates SOS2, promotes the binding of SOS2 to 14-3-3 and inhibits the activity of SOS213. At the same time, these kinases inhibit the activity of ATPase on the membrane12. Under salt stress, the annexin (ANN) protein mediates the production of an early transient Ca2+ signal and leads to an increased Ca2+ level in a short period of time14. When Ca2+ reaches a certain concentration, Ca2+ binds to 14-3-3 and ScaBP5/8, which causes 14-3-3 to dissociate from SOS210 and bind to PKS5/24, inhibiting its kinase activity with the help of J3 (DnaJ homolog3) and eliminating the inhibition of SOS2 and ATPase15. In addition, SCaBP5/8 binds the activated SOS2, and the SCaBP5/8-SOS2 complex inhibits ANN activity, maintaining the intracellular Ca2+ concentration at a certain level14. Plasma membrane type H+-ATPase and vacuolar H+-ATPase are activated by SOS2, which establishes a proton gradient across the plasma or vacuolar membrane that drives SOS1 or NHX activity to promote cellular ion equilibrium9. In addition to the well characterized ANN–14-3-3–PKS5/24/J3–SCaBP5/8–SOS2–SOS1 signaling pathway and ANN–14-3-3–PKS5/24/J3–SCaBP5/8–SOS2–NHXs signaling pathway, there are still networks that are as yet uncharacterized.

So far, a few salt-responsive genes have been identified in potato, such as zinc finger protein gene (StZFP1)16; ethylene-responsive transcription factors (StERF1, StERF3 and StERF6)17; dehydration-responsive element-binding protein genes (StDREB1, StDREB2, StDREB3 and StDREB4)17,18. With the development of high throughput sequencing technology, RNA-seq has been more and more frequently used in plant stress resistance research. Meanwhile, the release of the potato reference genome sequence has provided the opportunity to identify salt-tolerance genes genome-wide in potato19. For example, expression profiling of the NAC transcription factor family in potato using RNA-seq disclosed that StNAC024, StNAC067 and StNAC108 are induced specifically under salt stress20. However, there are still insufficient expression data for revealing the molecular mechanisms of potato salt tolerance21. Isolating salt-tolerance genes and understanding the molecular mechanisms of salt tolerance are important for effectively improving salt tolerance in the existing cultivated potato species. Although sensitivity to salt is a characteristic of potato5, salt-tolerant tetraploid potato germplasm resources do exist22. For example, in a resource identification and evaluation study, we identified a tetraploid potato genotype, Longshu No. 5, with strong salt tolerance23. NaCl is most widely used to induce salt stress because of its higher solubility24,25. Hence, we subjected Longshu No. 5 to NaCl-induced salt stress and used RNA-seq to research the changes in the gene expression profiles to explore the salt-tolerance molecular mechanisms in potato and provide a basis for breeding salt-tolerant varieties.

Results

Transcriptome sequencing, assembly, and mapping

The tetraploid potato genotype Longshu No. 5 seedlings were treated with 500 mmol/L NaCl in the salt-stress experiment. Except for slight leaf rolling, which was observed after 48 h of NaCl stress, Longshu No. 5 looked similar to control seedlings grown without NaCl, while severe lodging and wilting were observed in the salt-sensitive genotype Qingshu No. 9 after 24 h (Fig. 1a). To obtain comprehensive gene expression information for the salt-stress response in S. tuberosum, we analysed the transcriptome profile of Longshu No. 5 (4 weeks seedling age) grown in tissue medium containing 500 mmol/L NaCl (High salt group, HS) or 0 mmol/L NaCl (Control group, CK) for 24, 48, 72, and 96 h (Fig. 1b).

Material and schematic of the experimental design. (a) Phenotypes of Longshu No. 5 treated with 500 mmol/L NaCl (HS) or 0 mmol/L NaCl (CK) for 0, 24, 48, 72 and 96 h. Qingshu No. 9 was salt-sensitive control. (b) Schematic showing the experimental design and nine sampling points for Longshu No. 5. Plants were collected from three replicates at each time point, and point ① is Longshu No. 5 at the 0 h time point.

RNA was extracted from the salt-treated seedling samples (HS groups; 24, 48, 72 and 96 h) and the untreated samples (CK groups; 0, 24, 48, 72 and 96 h) with three replicates per time point (total of 27 samples). The extracted RNA was verified to be of good quality (Supplementary Fig. S1; Supplementary Table S1). Subsequently, 27 libraries were constructed and sequenced using the Illumina HiSeqX10 platform with the 150-cycle paired-end sequencing protocol26. Through filtering raw data and assessing quality, an average of 11.74 G clean bases (77.89 million paired-end reads) per sample were obtained. The Q30 percentage (the proportion of bases with a quality value greater than 30) was 95%–97%, and more than 84.4% of the RNA-seq reads could be mapped to the DM reference genome (Supplementary Table S2).

Differential gene expression in response to NaCl treatment

Fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (FPKM) generated using DESeq. 2 was used as the measure of gene expression. An absolute log2 (fold change) value ≥1 and a false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.01 were set as the threshold for significant differential expression. Pairwise comparisons were performed between each HS group (24 h, 48 h, 72 h and 96 h) and the respective CK group to generate an HS DEG library, and the CK groups (0 h, 24 h, 48 h, 72 h and 96 h) were compared with each other to generate a CK DEG library. In total, 4297 and 5558 DEGs were detected for the CK groups and HS groups, respectively. A total of 5508 DEGs remained after removing genes in the CK-DEG library from the HS-DEGs library. 2810 of which were up-regulated and 2700 of which were down-regulated (the two DEGs of 5508 were up-regulated at some stress time points and down-regulated at others) (Table 1). A total of 289 (278 up-regulated and 11 down-regulated), 938 (595 up-regulated and 343 down-regulated), 1386 (921 up-regulated and 465 down-regulated), and 1730 DEGs (1134 up-regulated and 596 down-regulated) were detected after 24, 48, 72 and 96 h of NaCl stress, respectively (Table 1, Fig. 2). Venn diagram analysis showed that 25 (23 up-regulated and 3 down-regulated), 122 (34 up-regulated and 89 down-regulated), 208 (75 up-regulated and 133 down-regulated) and 562 (289 up-regulated and 273 down-regulated) DEGs were specifically regulated in Longshu No. 5 after 24, 48, 72 and 96 h of NaCl stress, respectively (Fig. 2). A total of 225 DEGs were commonly regulated at 24, 48, 72 and 96 h, including 221 up-regulated and 4 down-regulated genes. A sharp increase in the number of DEGs after 24 h of stress indicated that an adaptive response to NaCl stress was initiated in Longshu No. 5.

A venn diagram showing the overlap in differentially expressed genes (DEGs) under 24, 48, 72 and 96 h of NaCl stress in Longshu No. 5. (a), (b), and (c) are the Venn diagrams for all, up-regulated, and down-regulated genes, respectively. Due to PGSC0003DMG400004090 down-regulated at 24 h and up-regulated at 48 h, the numbers of up- and down-regulated genes don’t match the total number of genes at 24 h and 48 h.

GO and KEGG enrichment analysis of DEGs

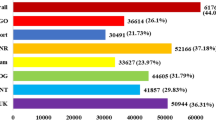

Gene ontology (GO) analysis was performed, and 2879 of 5508 DEGs was annotated to one or more GO terms. 142 GO terms that were significantly enriched in DEGs were categorized into 35 groups. Most of the enriched biological process GO terms were linked to metabolic process (11 terms) and ion or molecular transport (10 terms). Most of the enriched molecular function GO terms were related to organelle, organelle part, organelle lumen (10 terms), and the highest number of the DEGs were annotated to membrane (GO: 0016020; 401 DEGs). In the molecular function class, most DEGs including many TFs were annotated to nucleic acid binding (13 terms), followed by transporter activity (11 terms), ion binding (4 terms) and kinase activity (2 terms), which play a crucial role in salt stress response9, and a large number of the DEGs were annotated to catalytic activity (GO: 0003824; 1452 DEGs), ion binding (GO: 0043167; 856 DEGs) and transferase activity (GO: 0016740; 613 DEGs) (Fig. 3).

We next performed Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes orthologs (KEGG) analysis; 1760 DEGs had KEGG annotation and were assigned to 137 KEGG pathways. The photosynthesis, carbon fixation in photosynthetic organisms, citrate cycle (TCA cycle), spliceosome, ribosome, glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism categories were the most significantly enriched in DEGs (Supplementary Table S3). In addition, a large number of DEGs were annotated to MAPK signaling pathway-plant, oxidative phosphorylation, carbon fixation in photosynthetic organisms and glyoxylate, and dicarboxylate metabolism (Fig. 4).

Differential expression of transcription factors in response to NaCl treatment

Among the 5508 genes differentially regulated by NaCl stress, 274 encoded TFs belonging to 13 families. Most TFs were zinc finger proteins, followed by AP2-like ethylene-responsive transcription factor (AP2/ERF), MYB, bHLH, ZIP, WRKY, NAC, transcription factor TCP (TCP), heat stress transcription factor (HSF), Homeobox TFs, nuclear transcription factor Y (NFY), auxin response factor (ARF), MADS-box transcription factor (MADS) and others (Fig. 5).

About half of the TFs (53.3%) were up-regulated under salt treatment. Among the 60 zinc fingers proteins, there was an equal number of up-and down-regulated members, of which 10 genes were continuously up-regulated during salt stress. The gene PGSC0003DMG400023518, encoding ZTP2-14, was significantly up-regulated with a fold change of 4.5, 6.1, 8.2, and 8.4 at 24, 48, 72 and 96 h, respectively. Twenty-three of the 38 AP2/ERFs were up-regulated under salt treatment. Among the MYBs family, 19 were up-regulated; the expression of MYB36 (PGSC0003DMG400018331) and MYB108 (PGSC0003DMG400004612) continued to increase with prolonged salt stress, with a fold change in expression of 10.0 and 9.87 at 96 hours, respectively. Seventeen members of the bHLH family were up-regulated, especially transcription elongation factor SPT (PGSC0003DMG400004011), whose expression increased more than 4-fold after 72 h of stress. Among the ZIP, WRKY, NAC, TCP, HSF, Homeobox TFs, NFY, ARF, and MADS TF family members, 54 genes were up-regulated under salt stress in potato. Of these, WRKY45 (PGSC0003DMG400020206), WRKY61 (PGSC0003DMG400018081), TGA-2.1 (PGSC0003DMG400023678) and AGL15 (PGSC0003DMG401006771) were very lowly expressed (FPKM < 0.1) in the untreated group and moderately or highly expressed (FPKM ≥ 3.75) in the salt-treated group. WRKY7 (PGSC0003DMG400024961) and WRKY14 (PGSC0003DMG400015104) were continually up-regulated. In addition, NAC083 (PGSC0003DMG400011891) was highly expressed at 96 hours under NaCl stress with a FPKM value of 754.4. PGSC0003DMG400002484, encoding NFY, was highly expressed after 48 hours. In addition, four ARFs (PGSC0003DMG400012261, PGSC0003DMG400008065, PGSC0003DMG400003771, PGSC0003DMG400008081) down-regulated under NaCl stress (Supplementary Table S4).

Signal transduction-related proteins differentially expressed in response to NaCl stress

Protein kinases differentially expressed under salt stress

PKs act as a signal transducer or receptor protein and play a crucial role in phosphorylation events. We identified 259 PK genes with a moderate or high level of expression (FPKM ≥ 3.75), and many of them (124) encoded receptor-like kinases (RLKs), including LRR receptor-like kinases (LRR-RLKs, 46 members) and receptor-like protein kinases (RPKs, 26 members). LRR-RLKs and RPKs occupied 58.1% of RLKs. Besides, lots of serine/threonine protein kinases (STPKs) family were induced by salt stress, and 77.8% of CBL-interacting protein kinases (CIPKs) were all up-regulated (Supplementary Table S5). Mitogen-activated protein kinase families (MAPKs) play a crucial role in MAPK signaling pathways. There were 49 DEGs involved in the MAPK signaling pathway, of which 32 genes were up-regulated and 17 genes were down-regulated. For example, DEGs encoding an RPK (PGSC0003DMG400017864), a calmodulin-like protein (PGSC0003DMG400033565), an ethylene response transcription factor (PGSC0003DMG400014594), an ethylene receptor (PGSC0003DMG400017186), a catalase isoenzyme (PGSC0003DMG400009906), and a mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase (MAPKKK) gene (PGSC0003DMG400015021), were up-regulated by 8.51-, 7.63-, 5.51-, 4.08-, 3.37- and 3.09-fold, respectively, after 96 hours of salt stress. Transcription factor VIP1 (PGSC0003DMG400000799), which is involved in the MAPK signaling pathway, was previously shown to be induced by osmotic stress27 and it was also up-regulated in potato under salt stress. All three genes (PGSC0003DMG400002028, PGSC0003DMG400002029 and PGSC0003DMG400002027) encoding the pathogenesis-related protein 1b precursor, which is involved in the MAPK pathway, were down-regulated (Fig. 6; Supplementary Table S6).

Ca signaling pathway-related genes differentially expressed under salt stress

A total 53 DEGs belonging to 14 families related to Ca signal were induced by salt stress. About half of the DEGs (26 genes) encoded calcium-transporting ATPases (ACAs), CIPKs or calcium-binding proteins (CMLs). Of these, CIPK11 (PGSC0003DMG400020564), CIPK14 (PGSC0003DMG400011106, PGSC0003DMG400022019) and CIPK24 (PGSC0003DMG400006384) were continually up-regulated with increasing duration of salt stress, and there was a large change in the expression level of CML19, with fold-change values of 3.93-, 4.33-, 5.92- and 9.64-fold at 24, 48, 72 and 96 hours under salt stress, respectively. In addition, 19 DEGs encoding calmodulin-like proteins (CALMs), calmodulin-binding receptor-like cytoplasmic kinases (CRCKs), calcineurin B-like proteins (CBLs), calmodulin-binding proteins (CBPs), calcium-dependent protein kinases (CDPKs), calcium permeable stress-gated cation channels (CSCs), calmodulin-binding transcription activators (CAMTAs), calcium homeostasis regulators (CHoRs), calcium sensing receptors (CASs), calcium-binding mitochondrial carrier proteins (SCaMCs) and two pore calcium channel proteins (TPCNs) were up-regulated in response to salt stress. CRCK2 (PGSC0003DMG402006188), CBP60C (PGSC0003DMG400024785) and CBL10 (PGSC0003DMG400029942) were expressed at particularly high levels with FPKM values of 11042.33, 9438.67 and 7547.67, respectively, at 96 hours under salt stress (Table 2).

Stress-related protein genes differentially expressed in response to salt stress

Osmoregulation and carbohydrate metabolism-related genes under salt stress

Stress-induced proteins and carbohydrate metabolism-related proteins can participate in osmotic adjustment. Forty of the 53 DEGs encoding stress-induced proteins were up-regulated under salt stress with relatively high expression observed under stress (FPKM ≥ 3.75), such as chaperone proteins DnaJ, osmotin-like protein, proline-rich proteins (PRPs) and low-temperature and salt-responsive proteins (LTSRs) (Fig. 7). There were 13 DEGs encoding the chaperone protein DnaJ family and 92.3% of them were up-regulated. Pathogenesis-related protein STH-2-like (PGSC0003DMG400023435), abscisic acid and environmental stress-inducible protein TAS14 (PGSC0003DMG400015495), and osmotin-like protein (PGSC0003DMG400003042) were a large change in the expression level, with fold-change values of 8.06-, 7.79- and 7.04-fold at 96 hours under salt stress, respectively. In addition, LTSR (PGSC0003DMG400018240), encoded low temperature and salt responsive protein, was continually up-regulated with prolonged salt stress (Fig. 7). Eighteen DEGs encoded carbohydrate metabolism-related proteins and 69.6% of them were up-regulated. Twelve DEGs encoding UDP-glycosyltransferases (UGTs) were all up-regulated under salt stress, such as UGT73D1 and UGT91C1 were up-reguated by 6.38- and 3.13-fold at 96 hours, respectively; PGSC0003DMG400015579, encoding UDP-glycosyltransferase 74B1-like, was positively regulated by salt stress with fold-change values of 3.69, 3.42, 4.27 and 5.20 at 24 h, 48 h, 72 h and 96 h, respectively (Supplementary Table S7).

Antioxidant-related genes differentially expressed in response to salt stress

Sixty-one of the 87 DEGs related to antioxidant pathways were up-regulated and 26 were down-regulated under salt stress. A single DEG could be involved in one or more antioxidant pathways. Most of the DEGs encoded proteins related to glutathione metabolism (32 members), followed by peroxisome (26 members), peroxidase families (17 members), flavonoid biosynthesis (12 members), ascorbate oxidase (4 members) and flavone and flavonol biosynthesis (3 members) (Fig. 8a). Forty-eight out of the 87 DEGs had a large fold change in expression (|Log2 fold change | ≥2). These genes encoded peroxidase (POD), superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase isozyme 3 (CAT3), glutathione peroxidase 8 (GPX8), cytochrome P450 98A3 (CYP98A3), fatty acyl-CoA reductase 1-like (FARL1), glutathione S-transferase (GST), (S)−2-hydroxy-acid oxidase (HAO), UDP-glycosyltransferase (UGT), vinorine synthase-like (VSL), 2-hydroxyacyl-CoA lyase (HACL1), glutamate-cysteine ligase (GCSA), glutathione reductase (GSR), 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase 2 (KAT2), 2-hydroxyacyl-CoA lyase (HCAL), acyl-COA oxidase 4 (ACOX4), caffeoyl-CoA O-methyltransferase (CAMT), hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA lyase (HMGCL), acylsugar acyltransferase 3-like (AATL3), isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH), L-ascorbate oxidase-like (AOXL), L-ascorbate oxidase homolog (AOXH), long chain acyl-CoA synthetase 4-like (ACSL4), ornithine decarboxylase (ODC), and protein SYM1-like (PSL) (Fig. 8b). PGSC0003DMG400018031, encoding a lignin-forming anionic peroxidase-like protein, and PGSC0003DMG401007406, encoding a fatty acyl-CoA reductase 1-like protein, were up-regulated and with high fold-change values of 9.87 and 9.07, respectively. CAT3 (PGSC0003DMG400009906), SOD1 (PGSC0003DMG400010660), period circadian protein homolog genes PER7 (PGSC0003DMG400013654) and PER66 (PGSC0003DMG400024253) were up-regulated at all time points under salt stress.

Oxidative phosphorylation-related genes differentially expressed in response to salt stress

Thirty-four of the 44 DEGs involved in oxidative phosphorylation under salt stress were up-regulated and 10 were down-regulated. These DEGs encoded members of five oxidative phosphorylation complexes; 9 V-type and 4 F-type H+ transport ATPases, 2 cytochrome C oxidases, (COX17 and COX6B), the cytochrome reductases (ISP, Cyt1, QOR6 and QCR9), the succinate dehydrogenases (SDHA and SDHB) were up-regulated under salt stress in potato. The inorganic pyrophosphatase gene PGSC0003DMG400002775 was highly differentially expressed at each stress time point, with more than a 5-fold change in expression at 24 h. In addition, The NADH dehydrogenases Ndufa5 and Ndufa8 were also up-regulated, but cytochrome c oxidase subunit (Ndufa6), NAD(P)H-quinone oxidoreductase subunit (NdhK, NdhF and NdhD) were down-regulated with salt stress (Fig. 9). These DEGs indicated that oxidative phosphorylation was response to salt stress in potato.

Differential expression of ion transport-related genes under salt stress

Forty-three DEGs encoded ion adjustment-related proteins, including potassium transporters (KTs), sodium/hydrogen exchangers (NHEs), K+ efflux antiporters (KEAs), SLAH S-type anion channels, chloride channel proteins, potassium channel proteins, anion: sodium symporters, cation/H+ antiporters (CHXs), two pore calcium channel proteins (TPCNs), PM-type H+ -transporting ATPases (plasma membrane type, PMAs), V-type H+-transporting ATPases (vacuole type, ATPeVs) and V-type proton ATPase catalytic subunits. Among them, 34 were up-regulated under salt stress. PGSC0003DMG400004101, which encodes PMA, was the most highly expressed with FPKM values of more than 1000. PGSC0003DMG400012168, which encodes a cation/H+ antiporter, was highly differentially expressed with an 8.95-fold change in expression at 96 h. We also found four DEGs (PGSC0003DMG400022490, PGSC0003DMG400010663, PGSC0003DMG401021988, PGSC0003DMG402021988) encoding sodium/hydrogen antiporters (NHX4, NHX3 and NHX1), the key proteins exporting Na+ to vacuoles. The expression of these NHX genes increased gradually with extended duration of NaCl stress. In addition, the expression of the potassium channel AKT1 gene (PGSC0003DMG400001066) was induced and KAT3 genes (PGSC0003DMG400009614, PGSC0003DMG400009648) were down-regulated under salt stress, indicating that these proteins have different roles in response to salt in potato (Fig. 10).

Validation of differential gene expression

To validate the differential expression results from transcriptome sequence data analysis, the expression of 11 randomly selected genes differentially expressed under salt stress was evaluated by qRT-PCR. These genes include those encoding transcription factors (WRKY30, WRKY45 and WRKY71), MAPK kinases (MAPK4/6), ion channel proteins (AKT, NHX4, NHX3), CHX19, SOS1, an antioxidant enzyme (SOD) and aquaporin (PIP2-1). The relative expression levels calculated from qRT-PCR correlated with the log2 fold change values determined by RNA-Seq analysis. Thermographic correlation analysis showed that the correlation between relative expression and log2 fold change values at 24 h, 48 h, 72 h and 96 h were very high, with R2 values of 0.96, 0.90, 0.77 and 0.95, respectively (Fig. 11), indicating that the expression levels measured by qRT-PCR were basically consistent with those determined by RNA-seq and that the RNA-seq data were highly reliable.

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of differentially expressed genes. WRKY: encodes transcription factor WRKY; PIP2–1: encodes aquaporin PIP2–1; CHX19: encodes cation/H+ antiporter 19; AKT: encodes a potassium channel protein; NHX: encodes sodium/hydrogen antiporter; SOS1: encodes a sodium/hydrogen exchanger; SOD: encodes superoxide dismutase; MAPK4/6: encodes mitogen-activated protein kinase 4/6.

Discussion

The tetraploid potato genotype Longshu No. 5 is an excellent salt-tolerant material

Potato cultivars are highly heterozygous autotetraploids with complicated genetic backgrounds and are moderately sensitive to salt5, but there are the evidences that the potatoes have basis for salt tolerance28,29. Hence, further research to reveal the salt-tolerance mechanisms in potato is of profound significance for enhancing salt tolerance of potato. The tetraploid potato genotype Longshu No. 5 was obtained from screening an extensive collection of germplasm resources. No significant differences were noted in plant height and fresh weight for the salt-stressed Longshu No.5, indicating that the genotype has strong salt tolerance23. In addition, the genetic pedigrees of Longshu No. 5 and Qingshu No. 9 were quite different. It is uncertain if the transcriptome of the two genotypes can be directly compared to obtain the specific salt stress response genes in the salt-tolerant genotype. Therefore, in this study, Longshu No. 5 was subjected to NaCl-induced salt stress, and RNA-seq revealed that a large number of genes encoding TFs, PKs, stress-induced proteins, antioxidation proteins, ion transport proteins and Ca signaling-related proteins were differentially expressed. Meanwhile, many of the identified osmoregulation and antioxidant-related genes (Fig. 7 and Fig. 8) may be contributing to prevent lodging and wilting of potato plants (Fig. 1a). The results demonstrate that these differentially expressed genes have a strong salt-stress response in Longshu No.5.

The regulatory role of transcription factors in salt tolerance

TFs are important components of plant signal transduction pathways during stress and activate the expression of downstream targets through specific binding to cis-acting elements (CREs)30. TFs and their CREs are not only molecular switches for gene expression, but also the termini of signal transduction pathways. WRKY, AP2/ERF, MYB, ZIP, NAC and HSF are well known TF families involved in the response to salt stress31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38. For example, a complex containing OsWRKY71, OsMYB1 and OsDOF18 was found to bind and regulate OsRGLp2 (root germinating protein) under low temperature, high temperature, drought and salt stress39. In the present study, 274 (5.0%) of the 5508 genes differentially expressed under salt stress encoded TFs. These genes mainly belonged to 13 TF families and zinc finger, AP2/ERF, MYB, bHLH, ZIP, WRKY and NAC included lots of DEGs. Among the TFs identified as being differentially expressed in this study, several have been deemed to play roles in salt stress. For example, the expression levels of StWRKY7 and StWRKY14 were previously considered to be significantly up-regulated under salt stress40, and OsWRKY45 was reported to enhance tolerance to salinity in plants41. In our study, WRKY45 (PGSC0003DMG400020206) was up-regulated by 11.34-fold at 72 hours. In addition, we found that WRKY4, WRKY29, WRKY40, WRKY48 and WRKY61 were differentially regulated, implying that WRKY members might participate in regulating the response to salt stress in potato.

ERF TFs contain a conserved AP2⁄ERF DNA-binding domain42 and have been reported to regulate plant development and responses to biotic/abiotic stimuli including drought, salt and cold26. DREB1A binds to the C-repeat/DRE element and mediates high salinity-and dehydration-inducible transcription and confers resistance to salt, cold and drought stress in rice43. In this study, 23 of 38 ERF TFs were up-regulated under salt stress with DREB 2A-like proteins having expression changes of more than 9-fold, indicating that these proteins positively regulate the response to salt stress in potato.

The MYB domain family is one of the largest TF families, and members play regulatory roles in defense responses in plants44. Transgenic potato plants expressing IbMYB1, a sweet potato transcription factor, had enhanced salt stress tolerance and produced high amounts of secondary metabolites45. MYB108, which was up-regulated with salt stress in the present study, was previously reported being involved in the response to salt stress in Arabidopsis46. In addition, several MYB TFs, including LUX, AS1 and DIVARICATA, were found to be down-regulated under salt stress in our study, demonstrating that MYBs may positively or negatively regulate salt stress response in potato.

Basic leucine zipper (bZIP) TFs play key roles in salt stress signaling47,48. AtbZIP1 is associated with ABA signal transduction and is a positive regulator of plant tolerance to salt36. The potato bZIP TF StABF1 is induced in response to salt, drought and ABA stress48. The Agvip1, a bZIP TF, was up-regulated under salt stress in celery (Apium graveolens) cultivars49. We found that VIP1 (PGSC0003DMG400000799) was up-regulated at salt stress, which indicates that it may play an important role in response to salt stress in potato.

NAC proteins comprise a family of plant-specific TFs that are involved in the regulation of responses to diverse stresses, such as high salt, low temperature and drought7. Overexpressing a NAM, ATAF, and CUC (NAC) TF was considered to enhance salt tolerance in rice50. Some potato NAC TFs are only induced by salt stress, for example, StNAC024, StNAC067 and StNAC108. However, other NAC TFs such as StNAC030, which was up-regulated with salt stress in our study, were previously found to be induced under salt, mannitol and heat treatments20. A number of NAC TFs with up-regulated expression under salt stress were identified in this study revealing the potentially crucial role of NAC TFs in potato in salt tolerance.

In summary, zinc finger proteins, ERF, MYB, bHLH, ZIP and WRKY transcription factors responded better to salt stress. Therefore, we should focus on the relationship between these transcription factors and the upstream and downstream genes in response to salt stress in future potato studies.

Signal transduction-related proteins play a crucial role in the response to salt stress

Protein kinases

PKs, which include RLKs, MAPKs, CDPKs and CIPKs, play a key role in the response to salt and other abiotic stresses by sensing external signals and activating signal transduction pathways via phosphorylation of downstream genes3. RLKs, which form a large gene family in plants, convey signals to their target proteins in the cytoplasm by phosphorylating them under salt stress51. Recent studies have proven that OsRLCK253 (receptor-like cytoplasmic kinase 253)52, RPK1 (receptor-like protein kinase 1)53, and SRLK (S-receptor-like kinase)51 can be induced by salt stress or confer salt tolerance when overexpressed. In addition, RLKs have been shown to activate MAPK cascades and calcium signaling during abiotic stress54.

MAPKs play a pivotal role in plant stress resistance signal transduction. There are three kinds of serine/threonine protein kinases involved in MAPK signaling: MAPKKKs, MAPKKs and MAPKs, which transmit and amplify signals through a cascade reaction55. It has been shown in many plants that MAPKs can mediate the response to salt stress. In Arabidopsis, overexpression of active MKK9 protein enhances the sensitivity of transgenic seedlings to salt stress, whereas loss of MKK9 activity reduces salt sensitivity56, indicating MKK9 negatively regulates the response to salt stress. MAPK4, which was up-regulated in this study, was previously found to be highly expressed under salt conditions57. In addition, there are reports that AtMKKK4/6, ZmMKK1, GhMKK3, ZmMPK4, ZmMPK6/7 and SIMPK3/7 participate in the response to salt stress stimuli58,59,60,61,62. In this study, among 49 DEGs involved in the MAPK signaling pathway, 32 genes (including MAPKK9, MAPK4 and MAPK6) were up-regulated and 17 (including NPK1, YODA and MAPKK6) were down-regulated. Transcription factor VIP1, which is also involved in the MAPK signaling pathway, can be induced by salt stress31,49 and was up-regulated in potato under salt stress. In our study, the differential expression of MAPK-related genes demonstrates that signal cascade is stimulated by salt stress in Longshu No.5.

Ca signaling pathway-related proteins

The extracellular stress signal is first perceived by membrane receptors, which then activate complex intracellular signaling cascades that include the generation of Ca2+ second messengers. Then Ca2+ initiates stress tolerance signaling pathways, and these signals were processed based on the detection and decoding of Ca2+ sensors63. The Ca2+ sensors mainly include CBLs, CMLs, CDPKs, and CIPKs64. CIPK serine-threonine protein kinases interact with CBL proteins forming CIPK-CBL complexes, which play an essential role in the response to salt65,66. CBL1 (also known as SCABP5) acts as a positive regulator of salt stress responses67, and CBL10 (also known as SCABP8) interacts with the CIPK24 to protect Arabidopsis shoots from salt stress68. In addition, CIPK21, CIPK25 and CIPK31 regulate plant response to salt stress69,70,71. The CML genes CML9, CML37, CML38 and CML39 can be induced by salt72,73. Plants overexpressing CPK, which belongs to a subclass of CDPKs, showed enhanced salt tolerance with an increase in proline and decrease in malonaldehyde74. ZmCPK12 and OsCPK21 have been reported to confer tolerance to salt stress75,76. Twelve of the DEGs in this study encoding Ca2+ sensors (CBL1, CBL10, CML19, CML44, CRCK2, CBP60C, CPK11, CIPK3, CIPK11, CIPK14, CIPK18, and CIPK24) were identified in response to salt stress, demonstrating that Ca signal transduction pathways are activated to mitigate the effects of salt stress in potato.

In the present work, we detected many signal transduction-related genes, especially the differential expression of protein kinase-related genes, MAPK-related genes and Ca signal-related genes. This reveals that various signal transduction pathways are triggered by salt stress in potato.

Salt stress induces the expression of stress-related genes

Salt stress induces osmotic stress and oxidative stress in plants77. In this study, a total of 158 genes encoding osmoregulation, carbohydrate metabolism, and redox regulation related proteins were differentially expressed in response to salt stress. These genes are reported to resist or tolerate the abiotic stress78,79,80. For instance, under salt stress, compatible osmolytes are accumulated, these molecules are important for stabilizing biological structures81. In the study, encoding stress-related protein genes were found to be differentially expressed. These DEGs mainly encode PRPs, HSPs, LEA proteins, chaperone proteins, and LTSRs. Proline plays an irreplaceable role in osmotic adjustment. Under stress, proline protects membranes from damage and stabilizes protein structures, delta1-pyrroline-5-carboxylase synthase (P5CS), which is a key enzyme involved in proline synthesis, is induced by salt stress82. However, three PRP genes were identified to be down-regulated in our study, showing their distinctive roles in response to salt stress in potato. HSP proteins participate in plant responses to high salt83,84, and in the present study, five of six DEGs encoding HSP proteins were up-regulated under salt stress. LEA proteins can improve the resistance of plants to abiotic stress85, and HVA1, OsLEA3 and LEA14 have been shown to confer tolerance to salt stress86,87,88. A gene (PGSC0003DMG400011437) encoding a LEA protein was found to be up-regulated in this study with a change in expression of 5.59-fold at 24 hours. The differential expression of these stress-related genes in present study show the significance of them in protecting potato from salt-stress damage.

Carbohydrate metabolism plays a major role in salt-induced osmotic regulation89. UDP-glycosyltransferases are responsible for transferring sugar moieties onto a variety of small molecules, and contribute to the adaptation of abiotic stress90. Overexpression of UGT79B2/B3 significantly enhanced plant tolerance to low temperatures as well as drought and salt stress91 and ectopic expression of a stress-inducible glycosyltransferase (UGT85 family) from saffron enhanced salt and oxidative stress tolerance in Arabidopsis92. Twelve UDP-glycosyltransferase genes, including UGT73D1 and UGT91C1, were induced by salt stress in this study, indicating that genes involved in carbohydrate metabolism may play crucial roles in salt tolerance in potato.

Salt stress is associated with the rapid production of ROS in plants, and ROS trigger two main antioxidant defense systems (antioxidant enzymes and non-enzyme systems) for protecting cells and scavenging ROS93. Transcriptome sequencing of Pohlia nutans under salt stress indicated that expression of genes enoding antioxidant enzymes such as CAT, SOD, and POD was enhanced after salt treatment79. In this study, genes encoding POD (6 members), SOD (1 member) and CAT (1 member) proteins were up-regulated in response to salt stress. Glutathione S-transferase (GST), an important non-enzyme antioxidant, plays a role in cellular detoxification and stress tolerance. In potato the StGST genes are mainly repressed in response to abiotic stresses and induced in response to biotic stress94. However, all eight differentially expressed GST genes were up-regulated in the present study. This may be explained by differences in the genetic backgrounds of the salt-tolerant genotype used in this study and the genotype used in the previous study. Furthermore, we found that some genes encoding redox regulation-related proteins in the oxidative phosphorylation pathway, such as cytochrome C oxidases (COX17, COX6B) and cytochrome reductases (ISP, Cyt1, QOR6 and QCR9), were up-regulated, indicating that these genes may play positive roles in salt tolerance in potato.

The stress-related genes induced by salt stress may be helpful for maintaining secondary metabolic balance. In particular, the green and spreading leaves of Longshu No.5 exposed to salt stress may be associated with osmotic regulation and oxidation resistance. In addition, we suggest that the oxidative phosphorylation pathway may be involved due to the positive effects of its genes in response to salt stress in potato.

The potential molecular mechanisms underlying the response to salt stress in potato

High concentrations of salt (mainly Na+) in plant cells can induce ionic stress. Therefore, initiating the re-establishment of cellular ionic homeostasis under stress conditions is crucial12. SOS is a Ca2+ signal-dependent plant salt stress response pathway95, SOS2 is activated under salt stress, and phosphorylates and activates SOS1, which is a key element involved in Na+ transport from the cytoplasm to the apoplast96, and NHX, a vacuolar Na+/H+ exchanger97 for the purpose of ionic equilibrium. A gene (PGSC0003DMG400006384) encoding SOS2 was up-regulated in this study, indicating that this gene plays a positive regulatory role in the response to salt stress.

In our study, many genes related to ANN–14-3-3–PKS5/24/J3–SCaBP5/8–SOS2–SOS1 and ANN–14-3-3–PKS5/24/J3–SCaBP5/8–SOS2–NHXs signaling pathway were found to be differentially expressed. The genes encoding 14-3-3 proteins (PGSC0003DMG400017753, PGSC0003DMG400023590, PGSC0003DMG400012899), CBL10/SCaBP8 (PGSC0003DMG400029942), J3 (PGSC0003DMG400024784), CBL1/SCaBP5 (PGSC0003DMG400020493), CIPK11/PKS5 (PGSC0003DMG400020564), and CIPK14/PKS24 (PGSC0003DMG400022019, PGSC0003DMG400011106) were up-regulated in response to salt stress and ANNs (PGSC0003DMG402019427, PGSC0003DMG400019446, PGSC0003DMG400001879) were down-regulated. ANNs mediates early transient Ca2+ signal production, so the down-regulation of ANN may be beneficial for maintaining the intracellular Ca2+ concentration14. In addition, we found that PGSC0003DMG400022490, PGSC0003DMG400010663, PGSC0003DMG401021988 and PGSC0003DMG402021988, which encode NHX proteins; PGSC0003DMG400010630, which encodes SOS1; 13 V-ATPase genes and 3 PM-ATPase genes were up-regulated under NaCl stress, indicating that they may play a crucial role in maintaining the level of Na+ in the cytoplasm under salt stress in potato.

To date, the complete SOS pathway has yet to be established for salt-stress response in potato, and only a few genes of this pathway have been reported. Many SOS-related genes have been identified in our study, providing strong evidence that an SOS pathway mediates tolerance to salt stress in potato.

Materials and Methods

Plant materials

In a previous study, we screened 52 potato varieties for salt tolerance and found that Longshu No. 5 exhibited excellent growth and strong salt tolerance23. Specifically, the 25-day seedlings were cut into single stem segments, and the small segments were inoculated into Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium with the presence and absence of NaCl, with three replicates of 5 plants per replicate. After 4 weeks, the plant height, total biomass and fresh weight were measured. For Longshu No. 5, there was no significant difference in plant height between salt-stress and control conditions. Compared with the controls, there was a significant increase in fresh weight under salt stress. However, the height and fresh weight of Qingshu No. 9 samples were significantly decreased under salt stress compared with controls. Due to the fact that cultivated potato is an autotetraploid with a complex genetic background, the genetic pedigrees of Longshu No. 5 and Qingshu No. 9 were quite different. Meanwhile, considering the high cost of sequencing, we focused on the salt-stress response genes in salt-tolerant materials. Therefore, in this study, transcriptome analysis was only performed for the salt-tolerant genotype Longshu No. 5 under salt stress.

NaCl-induced salt stress

Seedlings of Longshu No. 5 were grown on normal MS medium for 4 weeks, then seedlings with the same shape, were selected. The stem segments with 7 ± 1 stem nodes were cut and inserted into MS medium containing 0 mmol/L or 500 mmol/L NaCl; 5 stem segments were inserted in each replicate with three replicates per treatment. Next the seedlings were cultured at (20 ± 2) °C with 16 hours illumination each day. At 0 (samples without treatment), 24, 48, 72 and 96 hours, plant samples were harvested from three replicates per treatment, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C.

RNA sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from frozen samples using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), and then purified using the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA integrity was determined using a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent) and quantified using a NanoDrop (Thermo Scientific). RNA samples (OD260/280 = 1.8 to 2.2, OD260/230 ≥ 2.0, RIN ≥ 8, >500 ng) were used for constructing sequencing libraries. The libraries were prepared using the NEBNext UltraTM RNA Library Prep Kit (E7530L) for Illumina (NEB, USA). Next, Qubit 2.0 fluorometer dsDNA HS Assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used to measure concentration of the resulting sequencing libraries, while the size distribution was analysed using an Agilent BioAnalyzer 2100. Finally, the libraries were sequenced on the Illumina HiSeq X Ten platform for generating 150-bp paired-end reads.

Data quality control and mapping clean reads to the genome

After sequencing, raw data were saved in FASTQ format. Raw reads were subjected to quality filtering using the NGS QC Toolkit v2.3.398. To obtain clean reads, the reads containing adapter or poly-N, and other low-quality reads were removed. The high-quality clean data were used for downstream data calculation and analyses, such as Q20, Q30 and GC-content. The clean reads were mapped back onto the reference genome sequence (PGSC_DM_v4.03) from the genotype of S. tuberosum group Phureja DM1-3 516 R44 (here referred to as DM), and were aligned using Tophat2 (v2.0.13)99. Meanwhile, we downloaded annotation files from the ENSEMBL plants database (ftp://ftp.ensemblgenomes.org/pub/plants/release-34/fasta/solanum_tuberosum/)100. Base on the reference genome and perfect-match or one-mismatch reads, we performed further annotation and analyses.

Differential expression analysis and enrichment analysis of DEGs

The expression values from the Illumina reads for each sample were determined with RSEM using default parameters101, Reads per kilobase of exon model per million mapped reads (FPKM) was calculated to estimate gene expression levels using HTseq-count102. The FPKM threshold value was set at 0.1. Differential expression analysis for each comparison was performed using DESeq. 2 from three biological replicates103,104. The adjusted P-values were used to control the false discovery rate (FDR). Genes with a corrected P-value < 0.05, fold-change ≥ 2 and FDR ≤ 0.01 were considered as DEGs. Pairwise comparisons were performed between each HS group (24 h, 48 h, 72 h and 96 h) and the respective CK group to obtain a salt-stress group (HS) DEG library, and the CK groups (0 h, 24 h, 48 h, 72 h and 96 h) were compared with each other to obtain a control group (CK) DEG library. In total, 4297 and 5558 DEGs were found from the CK groups and HS groups, respectively. The total salt-stress response DEGs were obtained by removing genes in the CK-DEG library from the HS-DEGs library.

To determine which category DEGs belonged to, we performed GO enrichment analysis using the GOseq R package. The technique applies the non-central hyper-geometric test to correct gene length bias105. KEGG enrichment was performed using KOBAS 2.0 to reveal significantly enriched signal pathways in DEGs106. GO terms and KEGG pathways with an adjusted P-value < 0.05 were considered to be significantly enriched in DEGs.

Quantitative real-time PCR validation

To verify RNA-seq results, qRT-PCR was performed for 11 randomly selected DEGs (Supplementary Table S8). The samples used for RNA-seq and qRT-PCR analysis were the same ones. The qRT-PCR protocol used here is described in our previous study26. The experiment was performed using a Roche LC480 II System (Roche Diagnostics Nederland BV, Almere, the Netherlands) with three technical and three biological replicates. The 2−∆∆Ct method107 was used to calculate the relative expression level of each gene using the internal reference gene actin. All primers used in this study (Supplementary Table S8) were designed using Primer 5.0.

Data availability The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Raw RNA-seq data from the study have been deposited in the NCBI SRA (sequence read archive) database under accession PRJNA577000.

References

Zhu, J. K. Plant salt tolerance. Trends Plant Sci 6, 66–71, https://doi.org/10.1016/S1360-1385(00)01838-0 (2001).

Munns, R. & Tester, M. Mechanisms of salinity tolerance. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 59, 651–681, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092911 (2008).

Zhu, J. K. Salt and drought stress signal transduction in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 53, 247–273, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.arplant.53.091401.143329 (2002).

Hmida-Sayari, A. et al. Identification of salt stress-induced transcripts in potato leaves by cDNA–AFLP. Mol. Biotechnol. 30, 31–40, https://doi.org/10.1385/MB:30:1:031 (2005).

Subhash, C. G., Koh-ichiro, A., Akihito, K. & Masanori, T. Effect of salt stress on some chemical components and yield of potato. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 47, 467–475, https://doi.org/10.1080/00380768.2001.10408411 (2001).

Hmida-Sayari, A. et al. Overexpression of Δ1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase increases proline production and confers salt tolerance in transgenic potato plants. Plant Sci. 169, 746–752, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plantsci.2005.05.025 (2005).

Zhu, J. K. Abiotic stress signaling and responses in plants. Cell. 167, 313–324, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.029 (2016).

Huang, G. et al. Signal transduction during cold, salt and drought stresses in plants. Mol. Biol. Rep. 39, 969–987, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-011-0823-1 (2012).

Yang, Y. & Guo, Y. Unraveling salt stress signaling in plants. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 60, 796–804, https://doi.org/10.1111/jipb.12689 (2018).

Yang, Z. J. et al. Calcium-activated 14-3-3 proteins as a molecular switch in salt stress tolerance. Nat. Commun 10(1199), 09181–2, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019- (2019).

Yang, Q. et al. Overexpression of SOS (salt overly sensitive) genes increases salt tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 2, 22–31, https://doi.org/10.1093/mp/ssn058 (2009).

Yang, Y. & Guo, Y. Elucidating the molecular mechanisms mediating plant salt-stress responses. New Phytol. 217, 523–539, https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.14920 (2018).

Zhou, H. P. et al. Inhibition of the Arabidopsis salt overly sensitive pathway by 14-3-3 proteins. Plant Cell. 26, 1166–1182, https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.113.117069 (2014).

Ma, L. et al. The SOS2-SCaBP8 complex generates and fine-tunes an AtANN4-dependent calcium signature under salt stress. Dev Cell. 48, 697–709, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.devcel.2019.02.010 (2019).

Yang, Y. et al. The Arabidopsis chaperone J3 regulates the plasma membrane H -ATPase through interaction with the PKS5 kinase. Plant Cell. 22, 1313–1332, https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.109.069609 (2010).

Tian, Z. D., Zhang, Y., Liu, J. & Xie, C. H. Novel potato C2H2-type zinc finger protein gene, StZFP1, which responds to biotic and abiotic stress, plays a role in salt tolerance. Plant Biol. 12, 689–697, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1438-8677.2009.00276.x (2010).

Bouaziz, D. et al. Identification and functional characterization of ten AP2/ERF genes in potato. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult 123, 155–172, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11240-015-0823-2 (2015).

Bouaziz, D. et al. Ectopic expression of dehydration responsive element binding proteins (StDREB2) confers higher tolerance to salt stress in potato. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 60, 98–108, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2012.07.029 (2012).

Xu, X. et al. Genome sequence and analysis of the tuber crop potato. Nature 475, 189–195, https://doi.org/10.1038/nature10158 (2011).

Singh, A. K., Sharma, V., Pal, A. K., Acharya, V. & Ahuja, P. S. Genome-wide organization and expression profiling of the NAC transcription factor family in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). DNA Res. 20, 403–423, https://doi.org/10.1093/dnares/dst019 (2013).

Rensink, W. A. et al. Gene expression profiling of potato responses to cold, heat, and salt stress. Funct. Integr. Genomics. 5, 201–207, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10142-005-0141-6 (2005).

Khrais, T., Leclerc, Y. & Danielle, J. D. Relative salinity tolerance of potato cultivars assessed by in vitro screening. Am. J. Potato Res. 75, 207–210, https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02854214 (1998).

Li, Q. et al. Establishment of vitro identification method for salt tolerance in potato and evaluation of salt tolerance of 52 germplasm. J. Plant Genet. Resour 19(4), 587–597, https://doi.org/10.13430/j.cnki.jpgr.20171029001 (2018).

Szabolcs, I. Review of research on salt-affected soils. Soil Science 131(1), 63, https://doi.org/10.1097/00010694-198101000-00016 (1981).

Wan, S. Q. et al. Transcriptomic analysis reveals the molecular mechanisms of camellia sinensis in response to salt stress. Plant Growth Regul. 84, 481–492, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10725-017-0354-4 (2018).

Yang, X. H. et al. Transcriptome profiling reveals effects of drought stress on gene expression in diploid potato genotype P3-198. Int. J. Mol. Sci 20, 852, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms20040852 (2019).

Takeo, K. & Ito, T. Subcellular localization of VIP1 is regulated by phosphorylation and 14-3-3 proteins. Febs Lett. 591, 1972–1981, https://doi.org/10.1002/1873-3468.12686 (2017).

Bilski, J. J., Nelson, D. C. & Conlon, R. L. Response of six wild potato species to chloride and sulfate salinity. Am. Potato J 65, 605–612, https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02908345 (1988).

Gao, H. J. et al. Ultrastructural and physiological responses of potato (solanum tuberosum L.) plantlets to gradient saline stress. Front. Plant Sci. 5, 787, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2014.00787 (2014).

Hussain, S. S., Kayani, M. A. & Amjad, M. Transcription factors as tools to engineer enhanced drought stress tolerance in plants. Biotechnol. Prog. 27, 297–306, https://doi.org/10.1002/btpr.514 (2011).

Hu, H. H. et al. Characterization of transcription factor gene SNAC2 conferring cold and salt tolerance in rice. Plant Mol. Biol. 67, 169–181, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11103-008-9309-5 (2008).

Song, H. et al. Global analysis of WRKY genes and their response to dehydration and salt stress in soybean. Front. Plant Sci. 7, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2016.00009 (2016).

Li, F. et al. Overexpression of a homopeptide repeat-containing bHLH protein gene (OrbHLH001) from dongxiang wild rice confers freezing and salt tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Rep. 29, 977–986, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00299-010-0883-z (2010).

Yoo, J. H. et al. Direct interaction of a divergent cam isoform and the transcription factor, MYB2, enhances salt tolerance in. Arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 3697–3706, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.m408237200 (2005).

Liu, J. X., Srivastava, R., Che, P. & Howell, S. H. Salt stress signaling in arabidopsis thaliana involves a membrane-bound transcription factor AtbZIP17 as a signal transducer. Plant Signal. Behav. 3, 56–57, https://doi.org/10.4161/psb.3.1.4889 (2008).

Sun, X. L. et al. The arabidopsis AtbZIP1 transcription factor is a positive regulator of plant tolerance to salt, osmotic and drought stresses. J. Plant Res. 125, 429–438, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10265-011-0448-4 (2012).

Zhuang, J. et al. A rice OsAP23, functioning as an AP2/ERF transcription factor, reduces salt tolerance in transgenic arabidopsis. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 31, 1336–1345, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11105-013-0610-3 (2013).

Tian, Z. D. et al. The potato ERF transcription factor stERF3 negatively regulates resistance to phytophthora infestans and salt tolerance in potato. Plant Cell Physiol. 56, 992, https://doi.org/10.1093/pcp/pcv025 (2015).

Deeba, F., Sultana, T., Mahmood, T., O’Shea, C. & Naqvi, S. M. S. Involvement of WRKY, MYB and DOF DNA-binding proteins in interaction with a rice germin-like protein gene promoter. Acta Physiol. Plant. 39, 189, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11738-017-2488-4 (2017).

Huang, S. G. & Liu, Y. S. Genome-wide analysis of WRKY transcription factors in solanum tuberosum. Chin. J. Appl. Environ. Biol. 19, 205–214, https://doi.org/10.3724/sp.j.1145.2013.00205 (2013).

Viana, V. E., Busanello, C., da Maia, L. C., Pegoraro, C. & de Oliveira, A. C. Activation of rice WRKY transcription factors: an army of stress fighting soldiers. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 45, 268–275, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pbi.2018.07.007 (2018).

Riechmann, J. L. et al. Arabidopsis transcription factors: Genome-wide comparative analysis among eukaryotes. Science 290, 2105–2110, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.290.5499.2105 (2000).

Dubouzet, J. G. et al. OsDREB genes in rice, Oryza sativa L., encode transcription activators that function in drought-high-salt-and cold-responsive gene expression. Plant J. 33, 751–763, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01661.x (2003).

Sun, P., Zhu, X., Huang, X. & Liu, J. H. Overexpression of a stress-responsive MYB transcription factor of poncirus trifoliata confers enhanced dehydration tolerance and increases polyamine biosynthesis. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 78, 71–79, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2014.02.022 (2014).

Cheng, Y. J., Kim, M. D., Deng, X. P., Kwak, S. S. & Chen, W. Enhanced salt stress tolerance in transgenic potato plants expressing IbMYB1, a sweet potato transcription factor. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol 23, 1737–1746, https://doi.org/10.4014/jmb.1307.07024 (2013).

Chen, Y. H. et al. The MYB transcription factor superfamily of Arabidopsis: expression analysis and phylogenetic comparison with the rice MYB family. Plant Mol. Biol. 60, 107–124, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11103-005-2910-y (2006).

Liu, J. X., Srivastava, R., Che, P. & Howell, S. H. Salt stress responses in Arabidopsis utilize a signal transduction pathway related to endoplasmic reticulum stress signaling. Plant J. 51, 897–909, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-313x.2007.03195.x (2007).

Muniz Garcis, M. N. et al. Characterization of StABF1, a stress-responsive bZIP transcription factor from Solanum tuberosum L. that is phosphorylated by StCDPK2. in vitro. Planta. 235, 761–778, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00425-011-1540-7 (2012).

Li, Y., Chen, Y. Y., Wang, F. & Xu, Z. S. & Qian Jiang. Isolation and characterization of the Agvip1 gene and response to abiotic and metal ions stresses in three celery cultivars. Mol. Bio. Rep. 41, 6003–6011, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-014-3478-x (2014).

Hu, H., Dai, M., Yao, J., Xiao, B. & Xiong, L. Overexpressing a NAM, ATAF, and CUC (NAC) transcription factor enhances drought resistance and salt tolerance in rice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 12987–12992, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0604882103 (2006).

de Lorenzo, L. et al. A novel plant leucine-rich repeat receptor kinase regulates the response of Medicago truncatula roots to salt stress. Plant Cell. 21, 668–680, https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.108.059576 (2009).

Giri, J., Vij, S., Dansana, P. K. & Tyagi, A. K. Rice A20/AN1 zinc-finger containing stress-associated proteins (SAP1/11) and a receptor- like cytoplasmic kinase (OsRLCK253) interact via A20 zinc-finger and confer abiotic stress tolerance in transgenic Arabidopsis plants. New Phytol. 191, 721–732, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2011.03740.x (2011).

Hong, S. W., Jon, J. H. & Nam, K. H. G. Identification of a receptor-like protein kinase gene rapidly induced by abscisic acid, dehydration, high salt, and cold treatments in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. 113, 1203–1212, https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.113.4.1203 (1997).

Osakabe, Y., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K., Shinozaki, K. & Tran, L. S. Sensing the environment: Key roles of membrane-localized kinases in plant perception and response to abiotic stress. J. Exp. Bot 64, 445–458, https://doi.org/10.1093/jxb/ers354 (2013).

Hamel, L. P. et al. Ancient signals: comparative genomics of plant MAPK and MAPKK gene families. Trends Plant Sci 11, 192–198, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2006.02.007 (2006).

Xu, J. et al. Activation of MAPK kinase 9 induces ethylene and camalexin biosynthesis and enhances sensitivity to salt stress in. Arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 26996–27006, https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.m801392200 (2008).

Fu, S. F., Chou, W. C., Huang, D. D. & Huang, H. J. Transcriptional regulation of a rice mitogen-activated protein kinase gene, OsMAPK4, in response to environmental stresses. Plant Cell Physiol. 43, 958–963, https://doi.org/10.1093/pcp/pcf111 (2013).

Moustafa, K., de Vos, L. D., Leprinc, A. S., Savouré, A. & Lau- rière, C. Analysis of the Arabidopsis mitogen-activated protein kinase families: organ specificity and transcriptional regulation upon water stresses, Sch. Res. Exch. 225, 196–214, 1038.14/2008/143656 (2008).

Cai, G. H. et al. A maize mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase, ZmMKK1, positively regulated the salt and drought tolerance in transgenic. Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 171, 1003–1016, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jplph.2014.02.012 (2014).

Wu, T., Kong, X. P., Zong, X. J., Li, D. P. & Li, D. Q. Expression analysis of five maize MAP kinase genes in response to various abiotic stresses and signal molecules. Mol. Biol. Rep. 38, 3967–3975, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11033-010-0514-3 (2011).

Wang, C. et al. The cotton mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 3 functions in drought tolerance by regulating stomatal responses and root growth. Plant Cell Physiol 57, 1629–1642, https://doi.org/10.1093/pcp/pcw090 (2016).

Yu, L., Yan, J., Yang, Y. J. & Zhu, W. M. Overexpression of tomato mitogen-activated protein kinase SlMPK3 in tobacco increases tolerance to low temperature stress. Plant Cell, Tiss. Org. Cult. 121, 1–14, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11240-014-0675-1 (2015).

Mahajan, S., Pandey, G. K. & Tuteja, N. Calcium- and salt-stress signaling in plants: shedding light on SOS pathway. Arch Biochem Biophys 471, 146–158, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.abb.2008.01.010 (2008).

Kudla, J., Batistic, O. & Hashimoto, K. Calcium signals: The lead currency of plant information processing. Plant Cell. 22, 541–563, https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.109.072686 (2010).

Guo, Y., Halfter, U., Ishitani, M. & Zhu, J. K. Molecular characterization of functional domains in the protein kinase SOS2 that is required for plant salt tolerance. Plant Cell. 13, 1383–1400, https://doi.org/10.2307/3871302 (2001).

Liu, W. Z. et al. Rapeseed calcineurin b-like protein CBL4, interacting with CBL-interacting protein kinase CIPK24, modulates salt tolerance in plants. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 467, 467–471, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.10.034 (2015).

Cheong, Y. H. et al. CBL1, a calcium sensor that differentially regulates salt, drought, and cold responses in arabidopsis. Plant Cell 15, 1833–1845, https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.012393 (2003).

Quan, R. et al. SCABP8/CBL10, a putative calcium sensor, interacts with the protein kinase SOS2 to protect Arabidopsis shoots from salt stress. Plant Cell 19, 1415–1431, https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.106.042291 (2007).

Pandey, G. K. et al. Calcineurin B-like proteins-interacting protein kinase, CIPK21, regulates osmotic and salt stress responses in. Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 169, 780–792, https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.15.00623 (2015).

Luo, Q. et al. BdCIPK31, a calcineurin b-like protein-interacting protein kinase, regulates plant response to drought and salt stress. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 1184, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2017.01184 (2017).

Meena, M. K., Ghawana, S., Dwivedi, V., Roy, A. & Chattopadhyay, D. Expression of chickpea CIPK25 enhances root growth and tolerance to dehydration and salt stress in transgenic tobacco. Front. Plant Sci. 6, 683, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2015.00683 (2015).

Magnan, F. et al. Mutations in AtCML9, a calmodulin-like protein from Arabidopsis thaliana, alter plant responses to abiotic stress and abscisic acid. Plant J. 56, 575–589, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-313x.2008.03622.x (2008).

Vanderbeld, B. & Snedden, W. A. Developmental and stimulus-induced expression patterns of Arabidopsis calmodulin-like genes CML37, CML38 and CML39. Plant Mol. Biol. 64, 683–697, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11103-007-9189-0 (2007).

Xu, J. et al. AtCPK6, a functionally redundant and positive regulator involved in salt/drought stress tolerance in Arabidopsis. Planta. 231, 1251–1260, https://doi.org/10.2307/23391490 (2010).

Wang, C. T. & Song, W. Calcium-dependent protein kinase gene ZmCPK12 from maize confers tolerance to drought and salt stresses in transgenic plants. Acta Physiol. Plant. 35, 1659–1666, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11738-012-1208-3 (2013).

Asano, T. et al. Functional characterisation of OsCPK21, a calcium-dependent protein kinase that confers salt tolerance in rice. Plant Mol Biol 75, 179–191, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11103-010-9717-1 (2011).

Pommerrenig, B., Papini-Terzi, F. S. & Sauer, N. Differential regulation of sorbitol and sucrose loading into the phloem of Plantago major in response to salt stress. Plant Physiol. 144, 1029–1038, https://doi.org/10.2307/40065549 (2007).

Boriboonkaset, T. et al. Regulation of some carbohydrate metabolism related genes, starch and soluble sugar contents, photosynthetic activities and yield attributes of two contrasting rice genotypes subjected to salt stress. Protoplasma. 250, 1157–1167, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00709-013-0496-9 (2013).

Zhang, W., Liu, S. H., Li, C. C., Zhang, P. Y. & Zhang, P. Y. Transcriptome sequencing of Antarctic moss under salt stress emphasizes the important roles of the ROS-scavenging system. Gene. 696, 122–134, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2019.02.037 (2019).

Apse, M. P. & Blumwald, E. Engineering salt tolerance in plants. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 13, 146–150, https://doi.org/10.1016/s0958-1669(02)00298-7 (2002).

Liu, C. et al. Effect of drought on pigments, osmotic adjustment and antioxidant enzymes in six woody plant species in karst habitats of southwestern China. Environ. Exp. Bot. 71, 174–183, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envexpbot.2010.11.012 (2011).

Silva-Ortega, C. O. et al. Salt stress increases the expression of P5CS gene and induces proline accumulation in cactus pear. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 46, 82–92, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plaphy.2007.10.011 (2008).

Liu, A. L. et al. Over-expression of OsHsfA 7 enhanced salt and drought tolerance in transgenic rice. BMB Rep. 46, 31–36, https://doi.org/10.5483/BMBRep.2013.46.1.090 (2013).

Zou, J., Liu, C., Liu, A., Zou, D. & Chen, X. Overexpression of OsHSP17.0 and OsHSP23.7 enhances drought and salt tolerance in rice. J. Plant Physiol. 169, 628–635, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jplph.2011.12.014 (2012).

Battaglia, M. & Covarrubias, A. A. Late embryogenesis abundant (LEA) proteins in legumes. Front. Plant Sci. 4, 190, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2013.00190 (2013).

Xu, D. et al. Expression of a late embryogenesis abundant protein gene, HVA1, from barley confers tolerance to water deficit and salt stress in transgenic rice. Plant Physiol. 110, 249–257, https://doi.org/10.1104/pp.110.1.249 (1996).

Hu, T. Z. OsLEA3, a late embryogenesis abundant protein gene from rice, confers tolerance to water deficit and salt stress to transgenic rice. Russ. J. Plant Physiol. 55, 530–537, https://doi.org/10.1134/s1021443708040158 (2008).

Jia, F. et al. Overexpression of late embryogenesis abundant 14 enhances Arabidopsis salt stress tolerance. Biochem Biophys Res. Commun. 454, 505–511, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.10.136 (2014).

Flowers, T. J. & Colmer, T. D. Salinity tolerance in halophytes. New Phytol 179, 945–963, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02531.x (2008).

Blanco-Herrera, F. et al. The UDP-glucose: Glycoprotein glucosyltransferase (UGGT), a key enzyme in ER quality control, plays a significant role in plant growth as well as biotic and abiotic stress in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Plant Biol. 15, 127, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-015-0525-2 (2015).

Li, P. et al. The Arabidopsis UDP-glycosyltransferases UGT79B2 and UGT79B3, contribute to cold, salt and drought stress tolerance via modulating anthocyanin accumulation. Plant J. 89, 85–103, https://doi.org/10.1111/tpj.13324 (2017).

Ahrazem, O. et al. Ectopic expression of a stress-inducible glycosyltransferase from saffron enhances salt and oxidative stress tolerance in Arabidopsis while alters anchor root formation. Plant Sci. 234, 60–73, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.plantsci.2015.02.004 (2015).

Chawla, S., Jain, S. & Jain, V. Salinity induced oxidative stress and antioxidant system in salt-tolerant and salt-sensitive cultivars of rice (Oryza sativa L.). J. Plant Biochem. Biotechnol. 22, 27–34, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13562-012-0107-4 (2013).

Islam, M. D. S., Choudhury, M., Majlishb, A. K., Islamc, T. & Ghosh, A. Comprehensive genome-wide analysis of glutathione S-transferase gene family in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.) and their expression profiling in various anatomical tissues and perturbation conditions. Gene. 639, 149–162, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2017.10.007 (2018).

Lin, H. et al. Phosphorylation of SOS3-LIKE CALCIUM BINDING PROTEIN8 by SOS2 protein kinase stabilizes their protein complex and regulates salt tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 21, 1607–1619, https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.109.066217 (2009).

Shi, H., Ishitani, M., Kim, C. & Zhu, J. K. The Arabidopsis thaliana salt tolerance gene SOS1 encodes a putative Na /H antiporter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 6896–6901, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.120170197 (2000).

Batelli, G. et al. SOS2 promotes salt tolerance in part by interacting with the vaculoar H -ATPase and upregulating its transport activity. Mol. Cell Biol. 27, 7781–7790, https://doi.org/10.1128/mcb.00430-07 (2007).

Patel, R. K. & Jain, M. NGS QC toolkit: a toolkit for quality control of next generation sequencing data. PLoS One. 7, e30619, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0030619 (2012).

Kim, D. et al. TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol. 14, R36, https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2013-14-4-r36 (2013).

Bolser, D. M., Staines, D. M., Perry, E. & Kersey, P. J. Ensemble plants: Integrating tools for visualizing, mining, and analyzing plant genomic data. In Plant Genomics Databases. Methods Mol. Biol 1533, 1–31, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4939-6658-5_1 (2017).

Li, B. & Dewey, C. N. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatics. 12, 323, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-12-323 (2011).

Anders, S., Pyl, P. T. & Huber, W. HTSeq-A Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 31, 166–169, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btu638 (2015).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq. 2. Genome Biol. 15, 550, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8 (2014).

Anders, S. & Huber, W. Differential expression analysis for sequence count data. Genome Biol. 11, R106, https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2010-11-10-r106 (2010).

Young, M. D., Wakefield, M. J., Smyth, G. K. & Oshlack, A. Gene ontology analysis for RNAseq: accounting for selection bias. Genome Biol. 11, R14, https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2010-11-2-r14 (2010).

Xie, C. et al. Kobas 2.0: a web server for annotation and identification of enriched pathways and diseases. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, W316–W322, https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkr483 (2011).

Livak, K. J. & Schmittgen, T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2 method. Methods. 25, 402–408, 10.1006/meth.2001.1262 (2001).

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31701485), the Central Public-interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund (Y2017JC56), Agro-scientific Research in the Public Interest of China (201503001), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2018YFD0200804), the China Agriculture Research System (CARS-9), and the Science and Technology Innovation Program of the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (CAAS-ASTIP-IVFCAAS).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: W.X.W. and X.Y.X.; Methodology: W.X.W. and G.C.L; Formal analysis and investigation: Q.L., Y.Z.Q., X.X.H. and H.Y.D.; Writing - original draft preparation: Q.L.; Writing - review and editing: X.Y.X. and Q.L.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Q., Qin, Y., Hu, X. et al. Transcriptome analysis uncovers the gene expression profile of salt-stressed potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). Sci Rep 10, 5411 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-62057-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-62057-0

This article is cited by

-

Investigating the genetic components of tuber bruising in a breeding population of tetraploid potatoes

BMC Plant Biology (2023)

-

Differential gene expression analysis under salinity stress in the selected turmeric (Curcuma longa L.) cultivars for curcuminoid biosynthesis

Molecular Biology Reports (2023)

-

A wheat WRKY transcription factor TaWRKY17 enhances tolerance to salt stress in transgenic Arabidopsis and wheat plant

Plant Molecular Biology (2023)

-

A high-throughput RNA-Seq approach to elucidate the transcriptional response of Piriformospora indica to high salt stress

Scientific Reports (2021)

-

Expression of a DREB 5-A subgroup transcription factor gene from Ricinus communis (RcDREB1) enhanced growth, drought tolerance and pollen viability in tobacco

Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture (PCTOC) (2021)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.