Abstract

Within the past decade, an alarm was raised about microplastics in the remote and seemingly pristine Arctic Ocean. To gain further insight about the issue, microplastic abundance, distribution and composition in sea ice cores (n = 25) and waters underlying ice floes (n = 22) were assessed in the Arctic Central Basin (ACB). Potential microplastics were visually isolated and subsequently analysed using Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) Spectroscopy. Microplastic abundance in surface waters underlying ice floes (0–18 particles m−3) were orders of magnitude lower than microplastic concentrations in sea ice cores (2–17 particles L−1). No consistent pattern was apparent in the vertical distribution of microplastics within sea ice cores. Backward drift trajectories estimated that cores possibly originated from the Siberian shelves, western Arctic and central Arctic. Knowledge about microplastics in environmental compartments of the Arctic Ocean is important in assessing the potential threats posed by microplastics to polar organisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Within the past decade, microplastic pollution emerged as an issue of concern in the Arctic Ocean due to the discovery of these contaminants in its sea ice1,2, surface and sub-surface waters3,4,5,6,7,8, deep sea sediments9,10,11, biota4,6,12,13 and mostly recently its snow14. Of the environmental compartments in this remote oceanic basin, it was shown that sea ice can function as a temporal sink, a secondary source and a transport medium for microplastics1,2. Historically, however, observational records of ‘dirty ice’, examination of Arctic ice cores, laboratory-based experiments and modelling studies were the first to highlight the potential for sea ice in the Arctic Ocean to trap, transport and redistribute sediments and various contaminants (i.e. metals, organochlorines, organophosphates, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons)15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27. Microplastics (plastic particles <5 mm in diameter) were first discovered in sub-sections of 4 ice cores retrieved from various locations in the Arctic Ocean1. In this initial study, a total of 6 types of synthetic polymers were reported in the ice cores and microplastic concentrations in Arctic sea ice were estimated (based on extrapolations) to be between (1.3–9.6) × 104 particles m−3. A second study2, subsequently examined 5 sea ice cores from the Arctic Ocean, reported on the presence of smaller (<100 µm in diameter), more diverse types of synthetic polymers (n = 17) and estimated (based on extrapolations) microplastic concentrations in Arctic sea ice to range between (1.1 × 106)–(1.2 × 107) particles m−3. Both studies1,2, while limited in scale and extent, collectively suggested that sea ice can function as a sink, source and transport medium for microplastics in the Arctic Ocean.

Within this remote oceanic basin, microplastic entrapment within sea ice potentially occurs during sea ice formation and drift while microplastic release occurs upon the melting of sea ice1,2,14. In the Arctic Ocean, while sea ice formation occurs over the central Arctic Ocean, the most important regions for this are the shallow Siberian shelves in the Eurasian Basin and the Beaufort Sea in the Amerasian Basin15. Microplastics entrapped within sea ice during its formation can potentially be reflective of microplastics present in seawater from known ice formation regions in the Arctic1,2. While the majority of sea ice melts in close proximity to its formation zone, some sea ice (i.e. that which forms over the Siberian shelves) is advected off the coast, joins the Transpolar Drift with some eventually exiting through the Fram Strait15,16. Sea ice from the Beaufort, Chukchi and East Siberian seas may become incorporated into the Beaufort gyre with some sea ice having the potential to exit this gyre and eventually join the Transpolar Drift17. Within the Arctic Ocean, sea ice dynamics are one of the key factors that potentially influences contaminant fate. Mobile sea ice floes in the Arctic Ocean are capable of entrapping contaminants along their drift pathways and playing a role in the redistribution of contaminants due to their eventual release upon melting of the ice2,16,19. Estimating backward sea ice trajectories is an important tool that facilitates an examination of sea ice sources, drift pathways, thickness changes and atmospheric processes acting on the ice cover2,28,29,30. When utilized in microplastic studies, backward sea ice trajectory data (i.e. sea ice sources and drift pathways) can be used to make inferences about potential regions where microplastic entrapment in sea ice occurred. The AWI ICETrack application, a lagrangian approach that traces sea ice backward in time using a combination of satellite-derived low-resolution drift products, is one available modelling approach that was utilised in the most recent study on microplastics in Arctic sea ice2. In the Arctic Ocean, sea ice has been identified as a temporal sink and secondary source of microplastics since contaminant release is projected to occur upon the melting of sea ice1,2. In the context of a changing climate, projections for Arctic sea ice include decreasing sea ice extent, reductions in sea ice thickness (less multi-year ice), alterations in the rate of sea ice drift, intensified melting of sea ice in the marginal zones and interruption of its Transpolar Drift28,31,32,33. These changing conditions will inevitably influence the dynamics of contaminant fate and transport in the Arctic Ocean, especially if the contaminants of interest are capable of being entrapped within, transported and subsequently released by sea ice.

Given that the 18 Arctic Large Marine Ecosystems (LMEs) support a diverse array of marine life34 and sea ice provides a range of microhabitats for numerous species35,36,37, an understanding of microplastic contamination in sea ice and surface waters of the Arctic Ocean is vitally important. The specific objectives of this study were to (i) provide a more spatially comprehensive assessment of microplastic concentration and composition in sea ice cores from the Arctic Ocean, (ii) assess the vertical distribution of microplastics in entire sea ice cores, (iii) estimate backward drift trajectories and identify source areas of sampled sea ice cores and (iv) assess microplastic abundance, distribution and composition in surface waters (beneath ice floes) in the Arctic Ocean.

Results

Quality control

Of the shipboard air contamination checks (n = 13) that were carried out, a single fibre (blue polyester fibre, 0.47 mm) was found. This indicates a low likelihood that microplastics were introduced to the samples as a result of airborne contamination. Of the method blanks (n = 15), 7 were free of contamination while the remainder contained either a single fibre (n = 6) or 2 fibres (n = 2). Fibres in the method blanks were polyester (n = 6), polyamide (n = 1) or a polyamide blend (n = 3). In order to account for any contamination that might have been introduced during ice core processing, a blank correction was applied whereby a single fibre was removed from each sub-section total. Additionally, if there were any matches between synthetic polymers found in the samples and those that came into contact with the samples (either during sampling or laboratory processing), these particles were excluded from the results.

Microplastic contamination in sea ice cores

A total of 2031 particles were isolated from the 25 sea ice cores and analysed using FT-IR spectroscopy. Of these, 501 particles were rejected due to (i) poor spectral matches, (ii) matches with polymers used during sample collection or processing and, (iii) identification as being natural or semi-synthetic polymers. A further 117 synthetic polymers were excluded from further analyses since they were categorized as being macroplastics (>5 mm). Of the 1413 confirmed synthetic polymers, 223 were removed during the blank correction processes. Subsequent analyses are therefore based on 1190 synthetic polymers <5 mm from the sea ice cores.

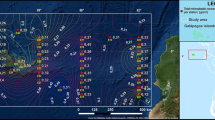

Microplastic concentration in sea ice cores (n = 25) from the Arctic Central Basin ranged between 2–17 particles L−1 with particle size ranging between 0.10 mm–4.99 mm (Fig. 1, Supplementary Table 1). Of the sampled cores, the majority had microplastic concentrations <8 particles L−1 (Fig. 1). The two cores with the highest microplastic concentrations were cores 1 (17 particles L−1) and 3 (15 particles L−1), (Fig. 1). In terms of polymer composition, a total of 9 types of synthetic polymers were found in the ice cores with an overall predominance of polyesters (57%) and polyamides (19%) followed by polyurethane (6%), styrene/acrylates (6%), polyacrylonitrile (6%), polyvinyl chloride (5%) and other polymers (1.3%) which included polypropylene and polyethylene (Supplementary Fig. 1). The majority of the microplastics that were found in the ice cores were fibres (79%) with the remainder (21%) being fragments. Size class distributions of microplastics in the ice cores were as follows: 0.1–0.5 mm (32%), 0.5–1 mm (20%), 1–2 mm (23%), 2–3 mm (13%), 3–4 mm (7%), 4–5 mm (4%), (Supplementary Fig. 1). In terms of colour, the majority of microplastics recorded in the sea ice cores were blue (53%) followed by red (10%), pink (9%), yellow (7%), black (5%), green (3.5%), transparent (3.5%), white (3%), grey (3%) and orange, purple and brown (3%).

Microplastic concentration in sea ice cores from the Arctic Central Basin by sampling location (a) and potential origin (b). (a) generated using Ocean Data View50.

Vertical distribution of microplastics in sea ice cores

Overall, there appears to be no consistent pattern in the vertical distribution of microplastics within sea ice cores (Fig. 2), as well as no overall correlation between sub-section depth of the ice core and microplastic concentration (Spearman’s Rank Correlation, p-values > 0.05). However, when individual ice cores were considered, core 8 was the only ice core for which there was a significant negative correlation between microplastic concentration and sub-section depth (Spearman’s Rank Correlation, rho = −0.74, p-value = 0.001). For certain ice cores (3, 6, 7, 8, 23) it was also apparent that microplastic concentration was comparatively higher in certain upper sub-sections of the core (Fig. 2). Microplastics were also shown to be pervasive throughout the majority of the ice cores. In 4% (n = 9, total sub-sections = 232) of all ice core sub-sections, no microplastics were found (relevant to cores 8, 10, 14, 15, 17, 19, 23).

Potential origin of sea ice

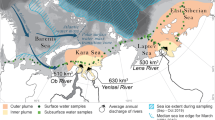

Backward trajectories of the ice cores indicated that they possibly originated from the (i) Siberian shelves in the Eurasian basin (i.e. Laptev Sea, East Siberian Sea), (ii) western Arctic (i.e. Beaufort Sea, Chukchi Sea) and, (iii) Central Arctic Ocean (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table 1). Of all the cores (n = 25), only 12 had a >75% match between measured sea ice thickness and model-predicted sea ice thickness (Fig. 3, Supplementary Table 1). Based on the backward trajectories of the sea ice cores, those cores which had the highest estimated microplastic concentrations i.e. >8 particles L−1 possibly originated in the Laptev, East Siberian and Chukchi Seas (Figs. 1, 3). Sea ice age estimations indicated that the majority of the sea ice cores were at least second year (SYI, n = 16, survived at least 2 melt seasons) and first year ice (FYI, n = 7, survived at least 1 melt season) with only two cores being classified as multi-year ice or greater than 3 years old (MYI, n = 2, survived at least 3 melt seasons), (Supplementary Table 1). Although univariate analyses indicated that there was a significant difference in microplastic concentrations between the different cores (Kruskal-Wallis, df = 24, p-value = 5.93 × 10−8), multivariate analyses (Principal Components Analysis), was unable to provide any useful discrimination between sea ice cores.

Backward trajectories derived using the AWI Ice Track application indicate formation zones for sampled sea ice in the (i) Laptev Sea (cores 1, 23, 25), (ii) East Siberian Sea (cores 5, 10, 17), (iii) Chukchi Sea (cores 7, 8, 11), (iv) Central Arctic Ocean (cores 9, 21, 13). [Trajectories shown here were for cores with a >75% match between model-predicted and field-recorded sea ice thickness, colours rep. months].

Microplastics in seawater beneath ice floes

A total of 189 particles were isolated from surface water beneath ice floes samples in the ACB. Of these, 47 were rejected for the above-mentioned reasons (i.e. those stated for the ice core samples). A further 17 synthetic polymers were excluded since they were categorized as macroplastics (>5 mm). Subsequent analyses were based on 125 synthetic polymers <5 mm from the surface water samples. Microplastic abundance in seawater beneath the ice floes (0–18 particles m−3, Fig. 4) were orders of magnitude lower than those reported for sea ice, (2 × 103) to (1.7 × 104) particles m−3 (extrapolated from particles L−1). Of the 22 sites where surface waters were sampled, only one site did not have microplastics detected. In terms of polymer composition, the majority of polymers detected in surface waters of the ACB were polyesters (70%) and polyamides (23%) with a minority of polyvinyl chloride (7%). Microplastic size class distributions were as follows: 0.25–0.5 mm (16%), 0.5–1 mm (18%), 1–2 mm (34%), 2–3 mm (14%), 3–4 mm (11%), 4–5 mm (6%), with the majority of microplastics (68%) being <2 mm. Overall, fibrous microplastics predominated (89%). In terms of colour, the majority of microplastics were blue (58%) and red (18%), with other colours such as transparent (5%), pink (4%), yellow (4%), grey (4%), purple (3%), green (2%), black (2%) and brown (1%) also being recorded.

Microplastic abundance in surface waters beneath ice floes in the Arctic Central Basin. (a) generated using Ocean Data View50.

Discussion

Microplastics, as evidenced by the present study, were ubiquitous in both sea ice cores and seawater underlying ice floes from the Arctic Central Basin (ACB). Microplastic concentrations in sea ice (estimations based on extrapolations from 25 sea ice cores, (2 × 103) to (1.7 × 104) particles m−3) were orders of magnitude higher than those reported for seawater beneath ice floes (0–18 particles m−3). While these findings corroborate those of previous studies1,2 that identified sea ice as a temporary sink for microplastics in the Arctic Ocean, it is collectively apparent that to date microplastic concentrations in Arctic sea ice have been underestimated. Analytical techniques (visual identification followed by FT-IR spectroscopy of potential microplastics) employed in the present study led to the exclusion of particles <100 µm from analysis and as such would have resulted in an underestimation of microplastic concentration in sea ice cores (number of cores = 25; range 2–17 particles L−1; extrapolated range (2 × 103)–(1.7 × 104) particles m−3). This is particularly relevant in light of the fact that the majority of microplastics in Arctic sea ice reported by a previous study2 using Imaging FTIR were <50 µm (number of cores = 5; extrapolated range (1.1 × 106) – (1.2 ×107) particles m−3). Although the previous study2 reported the highest microplastic concentrations thus far in sea ice, fibres were excluded from the analysis. By contrast, the present study reported a pre-dominance of fibrous microplastics (79%) in sea ice from the Arctic Ocean. It is therefore apparent that if either fibres or particles <100 µm are excluded from the findings, microplastic concentrations in sea ice will be underestimated. Furthermore, both the present study and a previous study2 showed that there was no consistent pattern in the vertical distribution of microplastics within sea ice cores. If isolated sub-sections of ice cores are used to estimate microplastic concentrations in Arctic sea ice as was done in a previous study (number of cores = 4, meltwater volumes 50–100 mL, extrapolated range 1.3–9.6 × 104 particles m−3)1, those extrapolations will either be underestimations or overestimations of microplastic concentrations. In the present study, meltwater volumes in ice cores ranged between 3–12 L. Extrapolations from particles L−1 to particles m−3 are relevant for comparison to microplastic concentrations in surface and sub-surface waters. However, when microplastic concentrations from <20 L of meltwater from a single ice core is used to estimate microplastic concentrations in 1,000 L or 1 m−3 of meltwater, such estimations are based on numerous assumptions and limited datasets (few ice cores, low meltwater volumes). It is therefore suggested that microplastic concentrations in sea ice should be reported as particles L−1.

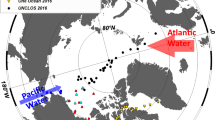

The identification of microplastic type (fibre, fragment, etc) and polymer composition is a critical component of microplastic studies as it provides investigators with some insight about the potential sources of microplastics in the environment. In the present study, 9 different types of synthetic polymers were reported in the sea ice cores while 3 were reported in surface waters underlying the ice floes. In both environmental compartments, the majority of microplastics were comprised of fibrous polyesters (57%- sea ice cores, 70%- surface waters) and polyamides (19%- sea ice cores, 23%- surface waters). Both polyesters and polyamides have a higher density than seawater38, thus raising the question as to why these particles were prevalent in both the sea ice cores and surface waters of the Arctic Central Basin. These findings were comparable to the first published study on microplastics in Arctic sea ice1 whereby it was reported that the most common synthetic polymers were polyesters (21%) and polyamides (16%). By contrast, although another study2 on microplastics in Arctic sea ice did report on the presence of polyester and polyamide, the most dominant synthetic polymer in the examined cores was polyethylene (48%) with the difference in findings possibly occurring due to the exclusion of fibres. In the western Arctic at the Bering and Chukchi Seas8, polyesters predominated in surface waters. In the present study, the majority of microplastics in sea ice cores (79%) and surface waters (89%) were fibrous. Similarly, in the Bering and Chukchi Seas8, fibrous microplastics were predominant in surface waters. In the marine environment, fibres may be originating from fishing gear, textiles due to laundering fabric and cigarette filters38. Laboratory experiments have indicated that the input of textile fibres into the marine environment can occur following the discharge of wastewater from domestic washings38,39,40,41,42,43. Recently, it was reported14 that both microplastics and microfibers were present in snow from ice floes in the Fram Strait which suggests that these particles could have been transported into the region by winds and been deposited onto ice floes and surface waters via snow. For the remote Arctic Ocean, it is difficult to pinpoint the exact origin of fibrous microplastics. Although definitive statements cannot be made about the origin of microplastics in surface waters or sea ice of the ACB, potential sources of these contaminants may include (i) riverine discharge from the Siberian and Canadian rivers7, (ii) influx of contaminated Pacific and Atlantic waters1, (iii) grey water discharge from vessels operating in the Arctic7 and, (iv) atmospheric deposition14.

Similar to the situation for sediments and other contaminants15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27, microplastic entrapment in Arctic sea ice potentially occurs during its initial formation over both the shallow marginal shelves of the Arctic Ocean and the deep central basin. In the present study, backward drift trajectories estimated that the sea ice floes from which the ice cores were sampled originated from the Siberian shelves in the Eurasian Basin, western Arctic and central Arctic. If microplastics were entrapped during sea ice formation in these areas and ice floes survived subsequent melt seasons, microplastic composition in sampled sea ice cores could be reflective of the microplastic composition in surface waters from these areas. At the marginal shelves of the Arctic, freshwater discharge from Siberian rivers; Dvina and Pechora (Barents Sea), Ob and Yenisei (Kara Sea), Lena (Laptev Sea) and Kolyma rivers (East Siberian Sea), and the Canadian Mackenzie river (Beaufort Sea)34,44, could be potential contributors to the microplastic load in Arctic sea ice. Since anthropogenic activities occur within the catchment areas of these rivers, the influx of freshwater into the Arctic basin is a potential pathway via which contaminants could enter this marine ecosystem45,46. Presently however, the contribution of riverine discharge to the microplastic load in Arctic sea ice remains uncertain due to the absence of field data. Pacific water influx into the Arctic Ocean through the Bering Strait also represents a potential source of contamination2 in that Pacific waters are influenced by anthropogenic activities that occur in northern America and eastern Russia. The Chukchi, Beaufort and East Siberian Seas which border the central Arctic are influenced by Pacific waters8 and thus any sea ice formed in these seas could potentially reflect microplastics that are present in the surface waters in these areas. The backtracking results that were presented in the present study must be interpreted with caution since there was a significant mismatch (>75%) between field and model-predicted ice thickness for 10 of the 25 ice cores (Supplementary Table 1). Although the AWI IceTrack application which generated these backward trajectories was validated using reconstructed pathways of real buoys, matches between ice thickness in the field and model-predicted ice thickness generally provide an indication of the reliability of the findings. The ice thickness mismatches could have been influenced by the fact that the tracking algorithm reconstructs the movement and evolution of sea ice that is mainly found in the Arctic Ocean and does not resolve dynamics and formation of new ice in leads (which is possibly where these specific ice cores were retrieved).

Microplastic incorporation into sea ice floes can also potentially occur during its drift across the central Arctic. Backward drift trajectories produced for sea ice sampled in the present study indicated that 24 of the 25 sea ice cores survived at least one summer melt and endured at least one winter period and that there was either drift across or initial sea ice formation within the ACB. These findings suggest that microplastics found in the sampled sea ice cores were potentially reflective of microplastics in surface waters of the ACB. Once present in surface waters of the central Arctic, periods of freezing will facilitate microplastic entrapment in newly formed ice or on the underside of existing ice floes. Microplastic presence in waters beneath ice floes (0–18 particles m−3) and sub-surface waters of the central Arctic7 indicates the availability of these particles for incorporation into sea ice, whether that is first year ice forming over the central basin or vertical ice growth on the underside of the floes. In the western Arctic8, microplastic abundance in surface waters of the Bering Sea ranged between 0.035–0.26 particles m−3 and in the Chukchi Sea between 0.086–0.31 particles m−3. Outside the central Arctic, microplastic abundance in surface Arctic waters south and southwest of Svalbard3 ranged between 0–1.3 particles m−3 and east of Greenland4 it ranged between 0.2–2.6 particles m−3 in 2005 and 0.8–4.5 particles m−3 in 2014. While conclusive statements cannot be made about differences in the reported microplastic abundances, it is plausible that sea ice functions as a secondary source of microplastics in the central Arctic and contributes to higher microplastic abundances. During transport, atmospheric deposition of microplastics unto the surface of an ice floe may also occur. A recent study14 reported that microplastics and microfibers were present in snow retrieved from ice floes in the Fram Strait. These findings suggested that these particles were potentially transported into the Arctic by winds and deposited unto the ice floes via snow14. Atmospheric fallout of microplastics suggests that these contaminants can be transported through the atmosphere and reach remote areas14,47,48. It is possible that microplastics can be transported into the Arctic region by winds and that these particles can be deposited either unto ice floes during transport or directly unto surface waters14.

Arctic sea ice is not the ultimate but an intermediate sink for microplastics. From a temporal perspective, seasonal environmental conditions (spring/summer melt seasons) influence sea ice melting and subsequent microplastic release in the Arctic Ocean. During summer, snow and ice melt off the upper portion of the ice floe with meltwater either running off the ice floe, percolating into the surface of the floe, accumulating in melt ponds or refreezing on the underside16. Summer melt periods can therefore facilitate the redistribution of microplastics within an ice floe in that particles that were present in the lower layers of an ice floe may eventually make their way to the top layer of an ice floe. In the present study, there was no consistent pattern in the vertical distribution of microplastic within the sea ice cores. Some of the sea ice cores, however, reflected comparatively higher concentrations of microplastics in the upper sub-sections and it is postulated that re-distribution processes may have resulted in this pattern. Of note is the fact that sea ice melting in the Arctic Ocean usually coincides with bursts of biological activity, i.e. ice algal blooms in spring and phytoplankton blooms in summer35. Sea ice in the Arctic Ocean functions as a key habitat for numerous species of marine organisms32,33,34,35,36,37. Presently, it remains uncertain whether microplastics are incorporated within the ice crystal structure or brine channels of sea ice and whether microplastics may pose a threat to sea ice meiofauna or in-ice fauna that inhabit sea ice. Marine organisms that live in close association with sea ice, specifically under-ice or sea ice macrofauna and sub-ice fauna, are likely to interact with microplastics once these particles are released into the underlying seawater from melting ice. In the Arctic Ocean, dominant under-ice fauna are the gammarid amphipods while sub-ice fauna include various species of copepods and fish such as the polar cod (Boreogadus saida) and Arctic cod (Arctogadus glacialis)37. Recently, microplastic fragments were reported in the stomachs of polar cod sampled from waters in the Eurasian Basin of the Arctic Ocean and north of Svalbard13 and in the digestive tracts of polar cod sampled in Arctic waters east of Greenland6. Based on the fact that interactions can potentially occur between marine organisms and microplastics in the Arctic Ocean, laboratory experiments are needed to elucidate the impact of those interactions with polar organisms. From a spatial perspective, regions which could be most at risk from an influx of contaminants (e.g. microplastics) from melting sea ice include nearshore areas over the marginal shelves, the central Arctic basin and the marginal ice zone e.g. Fram Strait, Barents Sea16,19,21,31.

The Arctic Ocean is a dynamic ecosystem where projections for Arctic sea ice in the context of a changing climate can inevitably influence contaminant fate and transport, especially if the contaminants of interest are capable of being entrapped within, transported and subsequently released by sea ice. Corroborating previous studies1,2, the present study evidenced that sea ice is capable of functioning as an intermediate sink, secondary source and a transport medium for microplastics in the Arctic Ocean. For the first time, microplastic presence in seawater underlying ice floes was reported for the central Arctic. Understanding the presence, sources, transport pathways and fate of microplastics in the Arctic Ocean is critical to determining the potential threats posed by such contaminants to marine organisms that inhabit or depend upon different environmental compartments in this ecosystem.

Methods

Sample collection

This study was conducted onboard Swedish icebreaker Oden during the Arctic Ocean 2016 expedition (August 8th to September 19th 2016). At 25 ice stations, sea ice cores (n = 25) were retrieved and seawater (n = 22) was pumped from beneath the ice and filtered onsite for microplastics. At each ice station, a suitable location upwind of all other site activities was selected and overlying snow was removed from an area of approximately 0.5 m2. Ice cores were collected using a Nordic ice drill with an attached Husqvarna X-series 326A125 motor and a stainless-steel core barrel of 12.5 cm diameter. At all sites, the goal was to completely penetrate the ice by drilling and reach the underlying seawater. A single ice core (n = 1) was retrieved at each site, placed into clean bags (polyethylene) and transported to the laboratory onboard the vessel for further processing. Once the sea ice core was retrieved at a site, water was then pumped from under the ice floe. A pre-cleaned polyvinyl chloride (PVC) hose (approximately 2 m in length) was inserted into the drilled hole. This hose was then connected to the inlet of a manual JABSCO Amazon Warrior pump (Model Number 29280-0000). Another hose of approximately 1 m in length was then connected to the outlet of the pump. Prior to any further connections, seawater was pumped from beneath the ice to flush the system of any contaminants. At this point, the flow rate of water through the system was manually checked by pumping seawater into a 1 L measuring cylinder. This was performed in triplicate in order to estimate the length of time needed for pumping the relevant volume of water. Following this, the hose from the outlet of the pump was positioned into the cover of a wooden stand containing a stainless-steel sieve (250 μm). This wooden stand with the sieve was positioned over a bucket into which filtered water flowed. The water that entered the bucket exited the site via a hose that was approximately 3 m in length. At 22 (of the 25) ice stations, water was manually pumped for at least 40 minutes thus ensuring that 1200 L of water was pumped at all sites, with the exception of two sites at which lower volumes (780 L, 1036 L) were pumped. Once pumping of water from beneath the ice was completed, the sieve was covered with aluminium foil, secured in the wooden stand and transported to the laboratory for further processing. At 3 (of the 25) ice stations, seawater could not be pumped from beneath the ice floe due to the incomplete penetration of the ice floe during drilling.

Laboratory processing and analyses

The outer surface of each ice core was scraped off using a boomerang scraper. A stainless-steel hand saw was then used to cut each ice core into 10 cm vertical subsections. Subsections were placed into individual clean Ziploc bags (polyethylene) and allowed to melt for 24–48 hours. Once melted, the water from each subsection was transferred to a graduated cylinder and its volume measured. Each Ziploc bag was rinsed in triplicate with Milli-Q water to ensure that all particles were transferred out of the bag. Water from each sub-section was filtered under vacuum onto glass microfiber paper (GF/C); Whatman: 47 mm, pore size: 1.2 μm, using a Buchner funnel and a vacuum flask. Each filter paper was folded, placed into an aluminium foil packet and stored in a freezer (−20 °C) until further processing. The sieve that was used for filtering water from beneath the ice was rinsed in triplicate and all water was also processed in the same manner (vacuum filtration of water and collection of particles onto glass microfiber paper). Potential microplastics were identified and isolated based on a previously described method49. Briefly, individual filter papers were visually examined under a dissecting microscope (Olympus SZX10) equipped with a polariser and camera (Q Imaging Retiga 2000R) and potential microplastics were identified based on characteristic features49. Potential microplastics from each sample were photographed, described according to form (fibre, fragment, etc) and length measurements were taken prior to transferring to a clean filter paper. Potential microplastics were assigned to two broad categories (fibres, fragments) and to six length categories: 0.1–0.5 mm, 0.5–1.0 mm, 1.0–2.0 mm, 2.0–3.0 mm, 3.0–4.0 mm, 4.0–5.0 mm. Filter papers with potential microplastics from each sample were stored in clean, labelled petri dishes. All potential microplastics were analysed by Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy on a Bruker Vertex 70 Infrared Spectrometer coupled to a Hyperion 1000 microscope according to a previously described method49. Briefly, each sample spectrum was compared with those of known standard polymers in the (i) Bruker Optics Attenuated Total Reflectance (ATR) Polymer and (ii) Synthetic Fibres ATR libraries. Samples which produced spectra with a match <60% were automatically rejected. All remaining spectra (>60%) were individually examined to ensure that there was clear evidence of peaks from the sample corresponding to known peaks of standard polymers. Overall, matches with >70% similarity were accepted while some between 60–70% similarity were accepted.

Method validation and contamination prevention

Several measures were taken to minimise contamination of samples. In the field, (i) microplastic sampling was conducted upwind of all other activities, (ii) nitrile gloves were used when handling ice cores, (iii) the manual pump used at the ice stations was flushed with water prior to pumping seawater, and (iv) the stainless steel sieve that was used at the ice stations had a wooden cover affixed to it during filtration. In the lab, (i) ice processing was conducted on a wooden surface, (ii) the wooden work area was washed down with Milli-Q water in between processing of individual ice core subsections, (iii) all equipment (scraper, saw) was washed with MilliQ water, (iv) lab coats, cotton clothing and gloves were worn during sample processing, and (v) all containers used during sample processing were cleaned using Milli-Q water. Checks were conducted to determine whether there was any contamination during sample processing. Clean petri dishes with filter paper were left exposed to the air during ice core and laboratory processing to determine if there was any airborne contamination. To determine whether there was any additional contamination during the processing of the melted sea ice, method blanks were conducted. For each method blank, 750 mL of Milli-Q water was placed into clean Ziploc bags and left for 24–48 hours. This water then underwent the exact processing as would have occurred for water from an ice core sub-section.

Data analyses

Source areas and backward drift trajectories for the sea ice cores were estimated using the AWI ICETrack application. The lagrangian approach traces sea ice backward in time using a combination of satellite-derived low-resolution drift products28. So far, ICETrack has been used in a number of publications to examine sea ice sources, pathways, thickness changes and atmospheric processes acting on the ice cover cover2,29,30. For each ice core, input to the application included sampling date and location (latitude, longitude) while output included a plot of the estimated pathway as well as ancillary data associated with the pathway. Predicted sea ice thickness by a thermodynamic model and measured sea ice thickness was compared in order to assess the validity of the findings for the various sea ice cores. All maps were generated using Ocean Data View (ODV) Version 4.7.1050 and all graphs were generated using R version 3.4.451. Univariate analyses were conducted to determine whether (i) there were significant differences in microplastic concentrations among the sea ice cores (Kruskall-Wallis) and, (ii) there were significant correlations between microplastic concentration and sub-section depth of the ice cores (Spearman’s Rank Correlation). Multivariate analysis, i.e. Principal Components Analysis (PCA), was conducted to provide further discrimination between the ice cores.

Data availability

All data related to this study is available without restriction.

References

Obbard, R. W. et al. Global warming releases microplastic legacy frozen in Arctic Sea ice. Earth’s Future 2, 315–320, https://doi.org/10.1002/2014ef000240 (2014).

Peeken, I. et al. Arctic sea ice is an important temporal sink and means of transport for microplastic. Nature Communications 9, 1505, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-018-03825-5 (2018).

Lusher, A. L., Tirelli, V., O’Connor, I. & Officer, R. Microplastics in Arctic polar waters: the first reported values of particles in surface and sub-surface samples. Scientific Reports 5, 1–9, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep14947 (2015).

Amélineau, F. et al. Microplastic pollution in the Greenland Sea: Background levels and selective contamination of planktivorous diving seabirds. Environmental Pollution 219, 1131–1139, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2016.09.017 (2016).

Cózar, A. et al. The Arctic Ocean as a dead end for floating plastics in the North Atlantic branch of the Thermohaline Circulation. Science Advances 3, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1600582 (2017).

Morgana, S. et al. Microplastics in the Arctic: A case study with sub-surface water and fish samples off Northeast Greenland. Environmental Pollution 242, 1078–1086, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2018.08.001 (2018).

Kanhai, L. K. et al. Microplastics in sub-surface waters of the Arctic Central Basin. Marine Pollution Bulletin 130, 8–18, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.03.011 (2018).

Mu, J. et al. Microplastics abundance and characteristics in surface waters from the Northwest Pacific, the Bering Sea, and the Chukchi Sea. Marine Pollution Bulletin 143, 58–65, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2019.04.023 (2019).

Bergmann, M. et al. High Quantities of Microplastic in Arctic Deep-Sea Sediments from the HAUSGARTEN Observatory. Environmental Science & Technology 51, 11000–11010, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.7b03331 (2017).

Mu, J. et al. Abundance and distribution of microplastics in the surface sediments from the northern Bering and Chukchi Seas. Environmental Pollution 245, 122–130, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2018.10.097 (2019).

Kanhai, L. K. et al. Deep sea sediments of the Arctic Central Basin: A potential sink for microplastics. Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers 145, 137–142, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsr.2019.03.003 (2019).

Fang, C. et al. Microplastic contamination in benthic organisms from the Arctic and sub-Arctic regions. Chemosphere 209, 298–306, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chemosphere.2018.06.101 (2018).

Kuhn, S. et al. Plastic ingestion by juvenile polar cod (Boreogadus saida) in the Arctic Ocean. Polar Biology, 1–10, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00300-018-2283-8 (2018).

Bergmann, M. et al. White and wonderful? Microplastics prevail in snow from the Alps to the Arctic. Science Advances 5, eaax1157, https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aax1157 (2019).

Pfirman, S., Lange, M. A., Wollenburg, I. & Schlosser, P. In Geological History of the Polar Oceans: Arctic versus Antarctic Vol. 308 (eds. Bleil, U. & Thiede, J.) (Springer, 1990).

Pfirman, S. L., Eicken, H., Bauch, D. & Weeks, W. F. The potential transport of pollutants by Arctic sea ice. Science of The Total Environment 159, 129–146, https://doi.org/10.1016/0048-9697(95)04174-Y (1995).

Reimnitz, E., Marincovich, L. Jr., McCormick, M. & Briggs, W. M. Suspension freezing of bottom sediment and biota in the Northwest Passage and implications for Arctic Ocean sedimentation. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 29, 693–703, https://doi.org/10.1139/e92-060 (1992).

Reimnitz, E., Clayton, J. R., Kempema, E. W., Payne, J. R. & Weber, W. S. Interaction of rising frazil with suspended particles: tank experiments with applications to nature. Cold Regions Science and Technology 21, 117–135, https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-232X(93)90002-P (1993).

Rigor, I. & Colony, R. Sea-ice production and transport of pollutants in the Laptev Sea, 1979–1993. Science of The Total Environment 202, 89–110, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-9697(97)00107-1 (1997).

Korsnes, R., Pavlova, O. & Godtliebsen, F. Assessment of potential transport of pollutants into the Barents Sea via sea ice—an observational approach. Marine Pollution Bulletin 44, 861–869, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0025-326X(02)00087-5 (2002).

Pavlov, V., Pavlova, O. & Korsnes, R. Sea ice fluxes and drift trajectories from potential pollution sources, computed with a statistical sea ice model of the Arctic Ocean. Journal of Marine Systems 48, 133–157, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmarsys.2003.11.024 (2004).

Hargrave, B. T., Vass, W. P., Erickson, P. E. & Fowler, B. R. Atmospheric transport of organochlorines to the Arctic Ocean. Tellus B: Chemical and Physical Meteorology 40, 480–493, https://doi.org/10.3402/tellusb.v40i5.16015 (1988).

Muir, D. C. G. et al. Arctic marine ecosystem contamination. Science of The Total Environment 122, 75–134, https://doi.org/10.1016/0048-9697(92)90246-O (1992).

Chernyak, S. M., Rice, C. P. & McConnell, L. L. Evidence of currently-used pesticides in air, ice, fog, seawater and surface microlayer in the Bering and Chukchi seas. Marine Pollution Bulletin 32, 410–419, https://doi.org/10.1016/0025-326X(95)00216-A (1996).

Melnikov, S., Carroll, J., Gorshkov, A., Vlasov, S. & Dahle, S. Snow and ice concentrations of selected persistent pollutants in the Ob–Yenisey River watershed. Science of The Total Environment 306, 27–37, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-9697(02)00482-5 (2003).

Pućko, M., Stern, G. A., Macdonald, R. W. & Barber, D. G. α- and γ-Hexachlorocyclohexane Measurements in the Brine Fraction of Sea Ice in the Canadian High Arctic Using a Sump-Hole Technique. Environmental Science & Technology 44, 9258–9264, https://doi.org/10.1021/es102275b (2010).

Pućko, M., Stern, G. A., Barber, D. G., Macdonald, R. W. & Rosenberg, B. The international polar year (IPY) circumpolar flaw lead (CFL) system study: The importance of brine processes for α- and γ-hexachlorocyclohexane (HCH) accumulation or rejection in sea ice. Atmosphere-Ocean 48, 244–262, https://doi.org/10.3137/OC318.2010 (2010).

Krumpen, T. et al. Arctic warming interrupts the Transpolar Drift and affects long-range transport of sea ice and ice-rafted matter. Scientific Reports 9, 5459, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-41456-y (2019).

Krumpen, T. et al. Recent summer sea ice thickness surveys in Fram Strait and associated ice volume fluxes. The Cryosphere 10, 523–534, https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-10-523-2016 (2016).

Damm, E. et al. The Transpolar Drift conveys methane from the Siberian Shelf to the central Arctic Ocean. Scientific Reports 8, 4515, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-22801-z (2018).

Newton, R., Pfirman, S., Tremblay, B. & DeRepentigny, P. Increasing transnational sea-ice exchange in a changing Arctic Ocean. Earth’s Future 5, 633–647, https://doi.org/10.1002/2016EF000500 (2017).

Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna (CAFF). Arctic Biodiversity Assessment: Status and trends in Arctic biodiversity. (Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna (CAFF), Akureyri, Iceland, 2013).

Serreze, M. C. & Meier, W. N. The Arctic’s sea ice cover: trends, variability, predictability, and comparisons to the Antarctic. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1436, 36–53, https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.13856 (2019).

Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP)/Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna (CAFF)/Sustainable Development Working Group (SDWG). Identification of Arctic marine areas of heightened ecological and cultural significance: Arctic Marine Shipping Assessment (AMSA) IIc. (Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP), Oslo, 2013).

Søreide, J. E., Leu, E., Berge, J., Graeve, M. & Falk-Petersen, S. Timing of blooms, algal food quality and Calanus glacialis reproduction and growth in a changing Arctic. Global Change Biology 16, 3154–3163, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2010.02175.x (2010).

Hardge, K. et al. The importance of sea ice for exchange of habitat-specific protist communities in the Central Arctic Ocean. Journal of Marine Systems 165, 124–138, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmarsys.2016.10.004 (2017).

Bluhm, B. A., Gradinger, R. R. & Schnack-Schiel, S. B. In Sea Ice (eds. Thomas, David N. & Dieckmann, Gerhard S.) (Wiley-Blackwell, 2010).

Andrady, A. L. The plastic in microplastics: A review. Marine Pollution Bulletin 119, 12–22, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2017.01.082 (2017).

Browne, M. A. et al. Accumulation of Microplastic on Shorelines Woldwide: Sources and Sinks. Environmental Science & Technology 45, 9175–9179, https://doi.org/10.1021/es201811s (2011).

Hernandez, E., Nowack, B. & Mitrano, D. M. Polyester Textiles as a Source of Microplastics from Households: A Mechanistic Study to Understand Microfiber Release During Washing. Environmental Science & Technology 51, 7036–7046, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.est.7b01750 (2017).

Napper, I. E. & Thompson, R. C. Release of synthetic microplastic plastic fibres from domestic washing machines: Effects of fabric type and washing conditions. Marine Pollution Bulletin 112, 39–45, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.09.025 (2016).

Almroth, B. M. C. et al. Quantifying shedding of synthetic fibers from textiles; a source of microplastics released into the environment. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 25, 1191–1199, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-017-0528-7 (2018).

De Falco, F. et al. Evaluation of microplastic release caused by textile washing processes of synthetic fabrics. Environmental Pollution 236, 916–925, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envpol.2017.10.057 (2018).

Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna (CAFF). State of the Arctic Marine Biodiversity Report. (Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna International Secretariat, Akureyri, Iceland, 2017).

Harms, I. H., Karcher, M. J. & Dethleff, D. Modelling Siberian river runoff — implications for contaminant transport in the Arctic Ocean. Journal of Marine Systems 27, 95–115, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0924-7963(00)00062-2 (2000).

Pavlov, V. In Arctic Alpine Ecosystems and People in a Changing Environment (eds. Orbaek, J. B. et al.) Ch. 18, 329–350 (Springer, 2007).

Allen, S. et al. Atmospheric transport and deposition of microplastics in a remote mountain catchment. Nature Geoscience 12, 339–344, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-019-0335-5 (2019).

Dris, R., Gasperi, J., Saad, M., Mirande, C. & Tassin, B. Synthetic fibers in atmospheric fallout: A source of microplastics in the environment? Marine Pollution Bulletin 104, 290–293, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.01.006 (2016).

Kanhai, L. K., Officer, R., Lyashevska, O., Thompson, R. C. & O’Connor, I. Microplastic abundance, distribution and composition along a latitudinal gradient in the Atlantic Ocean. Marine Pollution Bulletin 115, 307–314, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpolbul.2016.12.025 (2017).

Schlitzer, R. Ocean Data View, https://odv.awi.de (2019).

R Core Team, R: A language and environment for statistical computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, https://www.R-project.org 2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the invaluable support of the staff of the Swedish Polar Research Secretariat (especially Jeanette Axelsson, Robert Holden, Lars Lehnert, Asa Lindgren, Axel Meiton and Per Salo) and the crew of icebreaker Oden with the Arctic Ocean 2016 expedition. The expert guidance of Mr. Andrew Tonkin (University of Plymouth) during FT-IR analyses is also acknowledged. The first author also acknowledges the support of staff (Bengt Berglund, Ted Juliusen, Michelle Nerentorp, Sofi Jonsson, Nicke Juuso), fellow early career scientists (especially Hans-Martin Heyn, Luz Maria Ramirez) and other researchers (especially Asa Johannisson) during the expedition. Sampling in the Arctic Ocean was funded by the Swedish Polar Research Secretariat (SPRS) under the Early Career Scientist (ECS) Programme in which the first author was a participant. This work was also co-funded through a MARES Grant. MARES is a Joint Doctorate programme selected under Erasmus Mundus and coordinated by Ghent University (FPA 2011-0016). The funders had no role in study design, data collection, analysis and interpretation, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.K., I.O. and K.G. designed the study. K.G. provided training and logistical support during the AO16 expedition. L.K. and K.G. sampled sea ice cores and surface waters beneath ice floes during the AO16 expedition. L.K. processed sea ice cores, conducted FT-IR analyses, wrote the manuscript and analysed the results. T.K. estimated the backward trajectories and potential origin of the sea ice. I.O. provided feedback on the analyses. All co-authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kanhai, L.D.K., Gardfeldt, K., Krumpen, T. et al. Microplastics in sea ice and seawater beneath ice floes from the Arctic Ocean. Sci Rep 10, 5004 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-61948-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-61948-6

This article is cited by

-

Microplastic migration in porous media at various scales: a review

Environmental Chemistry Letters (2024)

-

Health risk of human exposure to microplastics: a review

Environmental Chemistry Letters (2024)

-

Suspended clay and surfactants enhance buoyant microplastic settling

Communications Earth & Environment (2023)

-

A review of recent progress in the application of Raman spectroscopy and SERS detection of microplastics and derivatives

Microchimica Acta (2023)

-

Distribution and characteristics of microplastics in beach sand near the outlet of a major reservoir in north Mississippi, USA

Microplastics and Nanoplastics (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.