Abstract

Predation often has consistent effects on prey behavior and morphology, but whether the physiological mechanisms underlying these effects show similarly consistent patterns across different populations remains an open question. In vertebrates, predation risk activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, and there is growing evidence that activation of the maternal HPA axis can have intergenerational consequences via, for example, maternally-derived steroids in eggs. Here, we investigated how predation risk affects a suite of maternally-derived steroids in threespine stickleback eggs across nine Alaskan lakes that vary in whether predatory trout are absent, native, or have been stocked within the last 25 years. Using liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectroscopy (LC-MS/MS), we detected 20 steroids within unfertilized eggs. Factor analysis suggests that steroids covary within and across steroid classes (i.e. glucocorticoids, progestogens, sex steroids), emphasizing the modularity and interconnectedness of the endocrine response. Surprisingly, egg steroid profiles were not significantly associated with predator regime, although they were more variable when predators were absent compared to when predators were present, with either native or stocked trout. Despite being the most abundant steroid, cortisol was not consistently associated with predation regime. Thus, while predators can affect steroids in adults, including mothers, the link between maternal stress and embryonic development is more complex than a simple one-to-one relationship between the population-level predation risk experienced by mothers and the steroids mothers transfer to their eggs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Predation is a potent force that shapes phenotypes over evolutionary and developmental time1,2. A major question in evolutionary biology is the extent to which selective pressures such as predation pressure have predictable effects on prey phenotypes and the role of natural selection in shaping consistent patterns of plasticity and/or the independent evolution of similar traits in closely related lineages (i.e. parallelism3,4,5,6). Examining whether different populations of prey respond to predators in the same manner has offered insights into this question7. For example, traits that protect prey and/or enable quick escape from predators often show evidence of parallelism across replicate populations with similar predation regimes (e.g. morphology7,8; antipredator behavior9,10). Predation pressure has also been shown to affect life history traits (e.g. age and size at maturity, offspring size and number), often in a parallel manner across populations with similar predation regimes11,12. Despite the many studies comparing morphology, behavior, and life history traits among populations that differ in predation risk, less is known about the predictability of changes in physiological mechanisms underlying these phenotypic responses to predation pressure.

The physiological response to acute and chronic stressors such as predation risk is highly conserved across vertebrates13,14 and largely mediated by the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA - mammals, reptiles and birds13) or the hypothalamic-pituitary-interrenal axis (HPI – fish15). The glucocorticoid steroid hormones produced by the HPA (cortisol in most mammals and fish; corticosterone in birds, rodents, reptiles and amphibians) are likely to be especially responsive to predation risk2,14. For example, encounters with predators increase short-term levels of cortisol in fishes16, corticosterone in birds17, and fecal cortisol metabolites in mammals18. Similarly, when predators vary seasonally and/or spatially over weeks and months, prey show elevated glucocorticoid levels that correspond to predation risk18,19 (but see20,21), potentially due to frequent encounters with predators. When predation risk is stable over generations, baseline levels and stress responsiveness can also be affected. For example, individuals from consistently high-predation risk populations have lower levels of cortisol after a stressor compared to individuals from low-predation risk21,22. How the evolutionary history of predation risk affects the physiological response to stress however, remains surprisingly understudied21,23.

While the glucocorticoid mediated stress response modulates metabolic and behavioral changes that enable animals to cope with stressors24, there are often other physiological consequences25. Fundamentally, steroid hormones are biochemically related to one another, with all steroids initially derived from cholesterol and linked via various enzymatic conversions26. Thus, physiological changes in response to predation pressure will involve multiple steroid hormones to orchestrate the phenotypic response to predation risk. For example, activation of the HPA axis can decrease the production of sex steroids such as progesterone and estradiol by the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis25,27,28. This link between the HPA and HPG axes creates a situation in which stressors are likely to influence levels of multiple steroids, not just glucocorticoids29. Furthermore, when predators encounter mothers provisioning eggs or gestating offspring, the hormonal consequences of predation risk have the potential to affect future generations through the hormones mothers transfer to offspring30,31.

Exposing females to stressors, such as predators, during reproduction can have long lasting effects on their offspring across a broad range of taxa30,32,33,34. Some of these effects are thought to be mediated by offspring exposure to increased levels of maternal glucocorticoids during development31,34,35,36,37, but not all maternal stress effects are mediated by embryonic exposure to maternal glucocorticoids38. Exposing females to stressors such as increased predation risk can also influence the amount of sex steroids transferred to eggs39. Taken together, increases in predation risk have the potential to not only elicit changes in glucocorticoid and sex steroid levels in a female but also to alter the levels of these steroids within her eggs and the developmental environment of her offspring.

The threespine stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus) adaptive radiation offers an opportunity to evaluate the extent of parallel changes in response to predation because postglacial freshwater populations within a region are all derived from a common marine ancestral type. Freshwater populations in disparate river drainages have been colonized independently and may thus be considered independent replicates40. Work in stickleback has drawn attention to parallel evolutionary changes in morphological and behavioral defenses (reviewed in8,41; note that parallel, rather than convergent, is the term used in this system42 and thus the term we use). These changes can be surprisingly rapid8,41,43. For example, the loss of armor plating after colonization of a freshwater habitat has been shown to occur in less than 10 years44. Here we examine whether these patterns extend to the physiological response and the potential maternal effects due to predation risk.

Specifically, we examined how predation risk affects maternally derived steroids in eggs, and thus the endocrine state experienced by developing offspring, in threespine stickleback. We assessed whether egg steroid content is associated with predation regime among three sets of freshwater lakes: those devoid of piscine predators for ca 6,000 generations (“predatory fish absent”), those exposed to rainbow trout for ca 6,000 generations (“native predatory fish”) and those exposed to rainbow trout for 25 or fewer generations (“stocked predatory fish”), including n = 3 lakes per predator regime. Although we do not have phenotypic or behavioral information on these populations, substantial previous work on stickleback has demonstrated the strong influence of predation on many phenotypic traits8,10,41,43,44.

Our sampling design allowed us to test three hypotheses. First, we examined whether the steroids that mothers deposit into their eggs show similar patterns in response to predation pressure. Given the important role of glucocorticoids in mediating the response to stressors, including predation, we predicted that populations with predatory trout would have higher egg glucocorticoid content in their eggs compared to populations without predatory trout. These elevated levels of glucocorticoids in eggs of females from high predation risk populations could be due to (1) encounters with predators resulting in acute stress responses during egg formation, (2) encounters with predators leading to the elevation of baseline glucocorticoids in females, and (3) evolved differences in baseline levels of glucocorticoids. Second, we examined whether patterns of maternal steroid provisioning in eggs of “stocked” populations that have experienced ~25 years with predatory trout resemble those of “native” predatory fish populations or those of populations in which predatory fish are “absent”. Note that morphological changes due to ecological conditions can occur in fewer than 10 years in stickleback44. Finally, we examined whether the steroids within eggs change as a coordinated package or each independently in response to predation risk. We expected glucocorticoids to be most responsive to variation in predation pressure, but given the interconnected nature of the HPA and HPG axes in vertebrates, we hypothesized that predation risk would simultaneously influence levels of numerous steroids within eggs. Therefore, we used liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectroscopy (LC-MS/MS) to simultaneously measure 21 steroids in individual egg clutches45,46. We then analyzed the egg steroid content data in a multivariate fashion in order to assess whether the components of the egg steroid profile change in concert or independently.

Materials and Methods

Study populations

Eggs were collected from females in nine lacustrine populations of threespine stickleback in the Matanuska-Susitna Valley of southcentral Alaska. This region was heavily glaciated until the most recent recession began ca. 12000 years ago providing a maximum age for freshwater populations in the region40. Oceanic stickleback colonized newly formed freshwater habitats giving rise to a remarkable adaptive radiation8,40. To examine how predators influence levels of maternally derived steroids in stickleback eggs, we took advantage of historical information on piscivorous fish in the nine study lakes. Three of the study lakes possess native populations of rainbow trout (Onchorynchus mykiss) (native: Beaver House, Kashwitna, South Rolly), three are historically devoid of piscivorous fish (absent: High Ridge, Jean, Whale), and three were devoid of piscivorous fish until stocking with rainbow trout began in 1992 (stocked: Bear Paw, Dawn, Vera) (see Table S1 for lake details). Recent studies have advocated the use of a geometric definition of (non)parallelism3,6. This method allows comparison of angles among phenotypic trajectories to examine repeated evolutionary patterns, but paired ancestral and descendant populations are necessary to estimate vectors3,6,47. Our design is unpaired48 without known ancestral populations for each lake, and thus we were not able to use this geometric method.

Egg collection

Between June 4 and 7, 2013 gravid female were collected from these lakes using unbaited minnow traps set for approximately 24 hr (range 18–26 hr) and eggs from 9–10 ovulated females in each population were extruded by gently squeezing the abdomen (N = 89 total clutches; 10 clutches from each Lake except for Whale Lake with absent predators where 9 clutches were collected). The eggs were immediately frozen on dry ice until transported to a freezer. Eggs were shipped overnight to the University of Illinois on dry ice and then were held at −20 C until steroid analysis.

All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations and all experimental protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at University of Illinois (no. 12118).

Steroid quantification via LC/MS/MS

The use of liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectroscopy (LC-MS/MS) has become an essential technique for quantifying steroids45. While often not as sensitive as traditional antibody-based techniques such as radioimmunoassay49, LC-MS/MS eliminates issues related to antibody cross-reactivity and can simultaneously quantify numerous steroids within a biological sample46. Steroid standards were purchased from Steraloids, Inc. (Newport, RI, USA) and prepared in methanol at a concentration of 1 mg/ml. Overall, 21 different steroids were quantified (steroid quantification details in Table S2) in order to achieve a holistic profile of steroid produced by the HPI and HPG axis. This resulted in levels of multiple glucocorticoids (n = 9), progestogens (n = 5), androgens (n = 5), and estrogens (n = 2) being characterized.

To prepare eggs for steroid quantification, eggs were thawed, weighed, and homogenized with a Potter-Elvehjem homogenizer. Steroids were first extracted with methanol50 by adding 2 ml of 100% methanol to sample homogenate and vortexing for 60 sec. Samples were stored at −20 °C overnight to precipitate neutral lipids and proteins. The samples were then spun at 2000 rpm at 0 °C for 20 min and the supernatant was poured to a 50 mL conical vial. A fresh 2 ml of methanol was added to the remaining pellet and the extraction process was repeated with the methanol supernatant being added to the first 2 ml of methanol extract. This 4 ml of methanol was diluted with 46 ml of MilliQ water (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) to bring the final volume up to 50 ml that was subsequently subjected to solid phase extraction of the steroids51. Additionally, standards were prepared to estimate the efficiency of solid phase extraction by adding 50 ng of each steroid to 4 ml of methanol and adding 46 ml of water.

Solid phase extraction was carried out with C18 Sep-pak cartridges (Waters, Ltd., Watford, UK) that were charged with 5 ml methanol and rinsed with 5 ml of water before the sample was loaded52,53. Samples were loaded under vacuum pressure at a drip rate of approximately 2 ml/min. Once samples had been pulled through, cartridges were rinsed with 5 ml of water. Steroids were finally eluted with diethyl ether and dried under nitrogen gas. Dried samples were submitted to the Metabolomics Lab of Roy J. Carver Biotechnology Center, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign for quantification.

Samples were analyzed with a 5500 QTRAP LC/MS/MS system (AB Sciex, Foster City, CA). The 1200 series HPLC system (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) includes a degasser, an autosampler, and a binary pump as described in53. The LC separation was performed on a Phenomenex C6 Phenyl column (2.0 × 100 mm, 3 μm.) with mobile phase A (0.1% formic acid in water) and mobile phase B (0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile). The flow rate was 0.25 mL/min. The linear gradient was as follows: 0–1 min, 80%A; 10 min, 65%A; 15 min, 50%A; 20 min, 40%A; 25 min, 30%A; 30 min, 20%A; 30.5–38 min, 80%A. The autosampler was set at 5 °C. The injection volume was 5 μL. Mass spectra were acquired under positive electrospray ionization (ESI) with the ion spray voltage of 5500 V. The source temperature was 500 °C. The curtain gas, ion source gas 1, and ion source gas 2 were 36 psi, 50 psi, and 65 psi, respectively. Multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) was used to measure steroids (Table S2). D9-progesterone (from m/z 324.1 to m/z 100.1) was used as an internal standard to control for inter-sample variation.

Statistical analyses

All steroids were converted to concentrations based on the wet mass of the clutch (ng of steroid per gram of eggs) after correcting for the average extraction efficiency (see Table S2 for % recovery and coefficients of variation for all steroids). We used Spearman correlations to explore how the measured steroids were related to one another.

To examine whether presence of piscivorous trout (absent, native, stocked) affects the steroids mothers transfer to their egg clutches, we used a permutational (non-parametric) MANOVA approach. First, we standardized all steroid concentrations using the ‘log’ standardization (decostand command) where x-values of zero are left zeros and logb(x) + 1 for all x-values greater than zero (b is the base of the logarithm), and specifying that standardization was within steroids (i.e. columns, MARGINS = 2)54,55. Second, we created a dissimilarity matrix on the standardized data of the steroids specifying Euclidean distances, similar to dissimilarity matrices used to compare communities in species abundances (R package vegan: vegdist command). Third, we compared the dissimilarity matrices among predation regime (absent, native, stocked) with Lake nested within Predation regime using a permutational (non-parametric) MANOVA approach with the program adonis (R package vegan54,55). We specified a permutation regime in which clutches/samples were permutated within Lake and Lake within Predation regime (Hank Stevens, personal communication). P-values were estimated with 10000 permutations and we specified “Euclidean distance” for the distance matrix. Although we examined the steroid concentrations (ng/g), it is unknown whether the concentration of different steroids vary with clutch size since there may be an endocrinological cue to increased clutch mass. For example, increased maternal production of progesterone could result in larger clutches that also have higher amounts of these steroids. Thus, we included wet clutch mass as a covariate in the MANOVA analyses of all steroids.

This permutational MANOVA approach requires an equal number of samples within each category to ensure appropriate permutations. Since one of our Lakes (Whale – absent) only had nine clutches, we created a 10th sample by averaging the traits from the existing nine samples from this Lake, thus making 10 samples per Lake and a total of 90 samples. This n = 90 dataset was used in the permutational MANOVA as well as in the factor analysis. To ensure this did not affect our conclusions, we also conducted all of the same analyses with a single random sample removed from each lake other than Whale, thus making 9 samples per Lake and a total of 81 samples.

Because the different steroids are related to one another within clutches and are likely to vary in a coordinated fashion, we used factor analysis with varimax rotation and maximum likelihood to extract underlying factors from the concentrations of the measured steroids (R package psych56,57). The number of factors to extract was assessed from parallel analysis and a scree plot. Using these factors, we examined the relationships among steroids as well as whether predation regimes differed in their factor scores. Specifically, we examined whether these extracted factors differed among predation regime using a similar permutational MANOVA analysis to that for the entire steroid profile (described above), with wet clutch mass included as a covariate. We also explored whether the variation in these extracted factors differed among predation regimes using a Fligner-Killeen test of homogeneity of variances. We used Spearman correlations to examine the relationships among these factors and clutch mass across predation regimes.

Because the factors were extracted from the entire data set, the relationships among steroids are not able to vary independently among the different predation regimes. While the permutational MANOVA examining the distance matrix among all measured steroids does allow these relationships to freely vary, we wanted to explore whether the make-up of the factors themselves might differ among predation regimes. We used the Common Principal Component Analysis program58 to compare the covariance matrices of the hormones (after the decostand standardization described above) for each predation regime, specifying the extraction of three principal components. We took a model building approach58 and focused on the model with the lowest AIC. Note that ‘Lake’ cannot be specified in these analyses, so we interpret these analyses with caution.

In separate mixed models, we examined how the concentration of cortisol (ng/g) in clutches, as well as the wet clutch mass, varied with predation regime including ‘Lake’ nested within ‘Predation regime’ (R package nlme59). To appropriately test for the effect of predation regime, we used the Satterthwaite degrees of freedom estimation (R package lmerTest60). Cortisol concentration was natural log-transformed based on the residuals while wet clutch mass was left untransformed. Wet clutch mass was included as a covariate in the cortisol analysis.

All analyses were conducted in R, version 3.4.461. Data was manipulated with R package dplyr62 and figures were made in R packages ggplot263, scatterplot3d64, and corrgram65. Means ± SE are given throughout. All data are available from Mendeley Data (McGhee et al. 2020, https://doi.org/10.17632/rngtxkx9y4.1).

Effect sizes from other studies

To compare our results to those of other studies, we estimated the effect sizes (Cohen’s d and eta2 66) from published studies measuring glucocorticoids in individuals from groups differing in predation risk in the field. We restricted studies to those examining the influence of natural levels of predation risk in the field (i.e. studies with manipulations of risk were excluded), as well as those measuring hormones in unmanipulated adults (i.e. other manipulations such as food level, were excluded). Note that these measures are snapshots of glucocorticoid levels in the field and thus, could be due to acute short-term changes and/or long-term baseline differences. To estimate effect sizes, we used the means and standard deviations of concentrations of plasma cortisol/corticosterone or of fecal cortisol metabolite either extracted from the paper, estimated from the figures using GraphClick (version 3.0.3)67 or by contacting the authors directly. We then used G*Power68 to estimate the power of our design to detect similar effect sizes using an ANCOVA and a MANOVA.

Results

Of the 21 measured steroids, β-cortol was not included in the analyses because it was not detectable in any of the 89 clutches sampled. Similarly, etiocholanolone, ketotestosterone, and estrone were also removed from the analyses as they were rarely detected in the sampled clutches (number of clutches detected: etiocholanolone = 1, ketotestosterone = 2, estrone =5; see Table S3 for the number of clutches in which steroids were detected). Thus, we included 17 steroids in our analyses. Cortisol was detected at the highest levels across clutches (steroid means and standard errors are in Table S3), which is consistent with previous results in sticklebacks69. Steroid levels were variable among individuals and most steroids were positively associated with one another (Fig. 1). Some of the strongest associations were within classes (Fig. 1; maximum rS: glucocorticoids = 0.86, progestogens = 0.78, sex steroids = 0.72) but glucocorticoids also tended to be positively associated with androgens (maximum rS: 0.60). The relationships among glucocorticoids and progestogens (maximum rS: 0.34) and progestogens and sex steroids (maximum rS: 0.42) were weaker (Fig. 1).

Correlations among the 17 hormones (standardized with the decostand method) for all predation regimes pooled (N = 89), with glucocorticoids, progestogens, and sex steroids highlighted in red, blue, and green respectively. Lower diagonal indicates the Spearman correlation coefficients with the shading and color showing the strength and direction (blue = positive, red = negative) of the correlations.

We extracted three factors from the 17 steroid concentrations based on the parallel analysis and scree plot. Multiple steroids from the major steroid classes loaded strongly on separate factors resulting in factors that corresponded surprisingly well to separate steroid classes (Table 1). Steroids within a single class were not the only ones loading on a factor however, and steroids from other classes also loaded on each factor (Table 1). For example, Factor 1 comprised seven positively loaded glucocorticoids, two positively loaded androgens, and one negatively loaded progestogen (DHP). Factor 2 comprised five positively loaded progestogens as well as one estrogen (estradiol), and one glucocorticoid (cortisone). Factor 3 comprised three positively loaded sex steroids (three androgens), one progestogen (DHP) and four glucocorticoids. Most steroids loaded strongly on a single factor except for cortisol, cortisone, and androstenedione which loaded positively on all three factors. Additionally, the progestogen DHP loaded negatively on Factor 1 and positively on Factors 2 and 3. Testosterone and dihydrocortisone both loaded positively on Factors 1 and 3 (Table 1). Thus, although steroids within classes tended to co-vary, several steroids from different classes also played roles across more than one factor. For each steroid, the three factors together explained much of the variance within eggs (h2 in Table 1).

The CPC analysis suggests that the three predation regimes likely share three common principal components (all CPC vs 3CPC: AIC = 533.47; 3CPC vs 2CPC: AIC = 571.21; 2CPC vs 1CPC: AIC = 579.60; 1CPC vs unrelated: AIC = 597.60). The PCs (or factors) from the three regimes are unlikely to show equality or proportionality (Equality vs Proportional: AIC = 792.40; Proportional vs CPC: AIC = 743.54). Note that ‘Lake’ cannot be specified in these analyses, so we interpret these analyses with caution since we cannot account for the substantial variation among lakes.

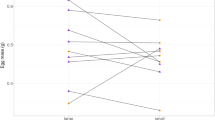

Although egg steroid profiles were variable among females and among lakes, we did not find a significant association between predator regime and the overall steroid profiles of eggs (Table 2a). Similarly, when the steroid profiles were summarized into three factors, predation regime did not significantly shape the dissimilarity matrix created from these steroid factors (Fig. 2, Table 2b). Restricting the factor analysis as well as the dissimilarity matrices to the reduced dataset (9 samples per lake; n = 81) instead of the dataset with the additional average sample for Whale Lake (10 samples per lake; n = 90) yields nearly identical results (Table S4). How these different steroid-factors were related to one another was also not associated with predation regime, and it is clear from the 3D plot, that the data from the different predation regimes overlaps entirely (Fig. 3). Steroid profiles were more variable among individuals from lakes without predators (absent lakes) compared to those with predators (native and stocked lakes) and variance within predation regimes (not accounting for the effect of lake) differed significantly for Factor 1 (chi-squared = 7.02, df = 2, P = 0.030) and Factor 2 (chi-squared = 8.74, df = 2, P = 0.013), but not Factor 3 (chi-squared = 0.51, df = 2, P = 0.773). Across all predation regimes, Factor 1 was positively associated with the wet mass of clutches (rS = 0.65, P < 0.01, N = 90), while Factor 2 and 3 were both negatively associated with the wet mass of clutches (Factor 2: rS = −0.23, P = 0.03; Factor 3: rS = −0.54, P < 0.01; N = 90) (Fig. 4).

Boxplots indicating the rotated factor scores extracted from the wet concentrations of 17 different steroids among lakes without piscivorous fish (green: absent), with native piscivorous fish (orange: native) and with stocked piscivorous fish (purple: stocked) (N = 90 clutches, shown as black symbols; major steroid loadings (from Table 1) are indicated on the x-axis). Boxes enclose the interquartile range with the median indicated as a thick line and whiskers extending to 1.5X interquartile range.

A three-dimensional plot illustrating the factor scores extracted from the wet concentrations of 17 different steroids for individuals in lakes either without piscivorous fish (green: absent), with native piscivorous fish (orange: native), or with stocked piscivorous fish (purple: stocked) with 95% ellipsoids (N = 90 clutches, shown as black symbols). Major steroid loadings, from Table 1, are indicated next to the axes.

Correlations among the three extracted factors from the 17 hormones (from Table 1) and wet clutch mass (g) for (A) absent (N = 30), (B) native (N = 30), and (C) stocked predation regimes (N = 30). Values on the lower diagonal indicate the Spearman correlation coefficients with the shading and color showing the strength and direction (blue = positive, red = negative) of the correlations.

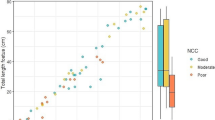

Despite being considered a major player in maternal stress, cortisol was not significantly associated with predation regime (Fig. 5; average concentration of cortisol ± SE: absent = 17.12 ± 2.68 ng/g, native = 11.49 ± 1.97 ng/g, stocked = 12.93 ± 1.12 ng/g; predation regime: F2,5.68 = 0.87, P = 0.465, wet clutch mass: F1,84.97 = 2.18, P = 0.143, random effect of lake: LRT = 7.26, P = 0.007, N = 89). Similarly, wet mass of clutch was not significantly associated with predation regime (average wet mass of clutch ± SE: absent = 0.165 ± 0.029 g, native = 0.173 ± 0.017 g, stocked = 0.233 ± 0.021 g; F2,5.94 = 0.84, P = 0.477, random effect of lake: LRT = 7.47, P = 0.006, N = 89). See Table S1 for population means and standard errors of cortisol and clutch mass.

Boxplots showing the wet concentration of cortisol (ng/g; controlling for extraction efficiencies) among lakes without piscivorous fish (green: absent), with native piscivorous fish (orange: native) and with stocked piscivorous fish (purple: stocked) (N = 89 clutches, shown as black symbols). Boxes enclose the interquartile range with the median indicated as a thick line and whiskers extending to 1.5X interquartile range.

We found 17 estimates from nine field studies of hormonal measures comparing either discrete years or populations that differed naturally in predation risk. There was substantial variation among these studies in the hormonal consequences of predation risk, with effect sizes ranging from d = 0.02 to d = 2.97 (Table 3). On average, individuals from high predation environments showed elevated glucocorticoid levels compared to individuals from low predation environments (Cohen’s d = 0.78 ± 0.18; Table 3). Our power in this study to detect a similar effect size in an ANCOVA analysis with three groups, a sample size of 30 samples per predation regime, and one covariate was 0.91. Furthermore, our power to detect an effect of f2 = 0.176 (with f2 = eta/(1 − eta)) using a MANOVA with a sample size of 90 and three groups was 0.78 for 20 measurements (i.e. hormones) and 0.99 for three measurements (i.e. factors). Thus we had sufficient power with our current dataset to detect the average effect size found in other studies. This again suggests that trout predation does not exert a consistently strong effect on the average steroid profiles of egg clutches in threespine stickleback from the field.

Discussion

We found that the 17 maternally-derived steroids detected in eggs primarily clustered together within classes (glucocorticoids, progestogens, and sex steroids) with particular steroids from each class loading strongly on more than one factor. It is important to note that the LC-MS/MS method used here measures the steroids precisely, thus covariation among steroids is not due to antibody cross reactivity (which can be a problem with other methods). While these results emphasize the modular yet interconnected nature of the endocrine response, surprisingly predation regime (absent, native, stocked) was not associated with these maternally-derived steroid egg profiles.

Our results demonstrate that many different maternally-derived steroids are detectable in unfertilized fish eggs and these steroids tend to positively covary and change in concert. Furthermore, particular steroids (e.g. cortisol, cortisone, dihydrocortisone, DHP, Testosterone) contribute strongly to multiple factors suggesting that they might be more influential to embryonic development than others. Most studies on the intergenerational effects of maternal stress, especially in egg laying vertebrates, have used exogenous manipulations of cortisol/corticosterone in mothers or in their eggs to mimic maternal stress28,34,35,37. While there is little doubt that the production of glucocorticoids in mothers is vital to how maternal stress effects are produced, changes in any or all of the maternally-derived steroids (as well as other components, such as miRNAs) in eggs could serve as effective signals of maternal stress. For example, maternal glucocorticoids, progestogens, androgens, and estrogens, have all been shown to influence offspring development in egg laying vertebrates52,70. Additionally, developmental effects can occur without direct exposure of offspring to maternal glucocorticoids38,39. For example, stickleback embryos are able to buffer themselves from exogenous manipulations of cortisol by actively transporting cortisol out of the egg via ATP-binding cassette transporters69,71. This suggests that the effects of maternal predator exposure on offspring behavior72,73,74, physiology75 and embryonic gene transcription76 in threespine stickleback are not mediated solely by embryonic exposure to maternal cortisol. Our results showing that many progestogens and androgens are positively correlated with glucocorticoids further emphasize the interconnected nature of the endocrine system and suggest that some assumptions, such as the negative relationship between androgens and glucocorticoids, might not be detectable in the maternally-derived steroids in eggs. Acknowledging that many maternal steroids play a role in offspring development and can vary in a coordinated fashion within eggs, will help us move beyond the focus on maternally derived glucocorticoid steroids2,38,77.

That we did not see a consistent pattern of predation regime on steroid profiles was unexpected (but see78), particularly given the role of glucocorticoids in dealing with predator encounters2,14,79, as well as the findings that stress-induced cortisol levels can be sensitive to rearing conditions80, heritable80,81, and respond to selection82. Not only is there no obvious difference between lakes with and without predatory trout, but exposure to piscine predators for 25 or fewer generations (stocked lakes) and ~6,000 generations (native lakes) have similar consequences for the steroid profiles. Although we do not have phenotypic measures of adults from our Alaskan populations, multiple studies have demonstrated parallel evolution of a variety of morphological traits in response to predation regime6. For example, fish from high predation populations differ in body shape and armor compared to low predation populations48,83,84, with these differences arising in fewer than 10 years in stickleback44. Additionally, our review of field studies suggests that population-level predation risk should be detectable in snapshots of circulating glucocorticoids. We had assumed based on this and the physiological consequences of predator encounters16 that adult females from these populations would differ in their circulating glucocorticoids (at least) and this would be reflected in their eggs. Sampling steroids of adults from these populations is clearly an avenue for future research but our results suggest that there is not a strong pattern between the predation risk experienced by mothers and the maternally-derived steroids in eggs.

Interestingly, we did find that stocked and native populations show less variation in both Factors 1 and 2 of their steroid profiles compared to populations in which predation is absent. It is possible that predators might exert stabilizing selection on prey and select for less variable and potentially more fine-tuned responses from prey. Mounting a stress response to each predator sighting in a high-predation environment can result in deleterious health consequences13,24,85. In order to cope with the chronic stress of repeated predator encounters, there is evidence that sensitivity to predator exposure and stress responsiveness might decrease, either as an evolved response11,86 or as a plastic response due to habituation85, or stress inoculation87,88. For example, high-predation risk populations tend to show lower levels of cortisol after a stressor compared to low predation risk populations21,22. As potent mediators of embryonic development36, cortisol and other maternally-derived hormones should be tightly regulated to prevent developmental disruptions31. Thus, it is possible that there has been strong selection for mechanisms that reduce the maternal stress response, or the downstream effects of maternal stress, resulting in the absence of any strong signature of predation risk in eggs (countergradient variation or cryptic evolution89). Disentangling the roles of plasticity and genetic effects in these patterns with the use of common garden studies over multiple generations and a reaction norm approach77 is an interesting area of future study.

How the steroid profiles measured here correspond to the phenotype under selection is unknown and different combinations of steroids might result in similar phenotypes with equivalent fitness (many-to-one mapping of form to function5,90). This “many-to-one” hypothesis has been proposed as an explanation for the inconsistencies between the strong patterns of parallelism in studies of morphological traits and the absence of such parallelism in studies of biomechanical and physiological traits as well as studies of the underlying genetics6,91,92,93,94 (but see95). The “many-to-one” hypothesis could be particularly relevant for steroids because of their role in phenotypic integration and coordinating suites of traits96,97. Interestingly, recent modeling efforts of hormonal pleiotropy has found that although the shapes of hormonally controlled resource allocation trade-offs show phenotypic convergence, they are often underlain by a variety of physiological mechanisms (i.e. different genetic solutions to the same problem)98. How steroid profiles translate into phenotypes and whether different combinations of maternally-derived steroids can give rise to similar offspring phenotypes with equal performance is clearly an area for future research.

The endocrine response is necessarily highly plastic (reviewed in14,24). Our review of field studies suggests that although predation risk is, in general, associated with increased glucocorticoid levels in prey, it is also highly variable in the strength of its effects. Some of the variation within high predation populations in steroid profiles, including our native and stocked predation regime lakes, could be due to variation among individuals in their personal experience with predators23. For example, steroids can vary with how recently, or how often, individuals have encountered a predator16,17. How females respond to predators may also have indirect consequences manifested as changes in foraging behavior and habitat use2,99 with such changes affecting female steroid levels1. Furthermore, experiences with predators are not the only factors capable of affecting the endocrine system. For example, during the mating season, gravid females interact with multiple courting and potentially aggressive males, they associate and observe other females, and they make foraging decisions and compete for resources in order to invest in egg production. The social environment alone is likely to vary within and among populations, may or may not be associated with predation regime, and can affect hormone levels100. Although this sensitivity to the external environment suggests that endocrine phenotypes might be more variable than other traits, corticosterone measures exhibit similar levels of variability to other phenotypic measures among populations101 and are generally repeatable across studies (r = 0.29102). Ecological similarities across lakes that are unrelated to predation regime might offer an explanation for the dominance of particular steroids across multiple factors as well as the similar factor loadings across regimes (CPC results). How plasticity due to individual experiences (to predators, mates, competitors) interacts with the background risk of predation in a population to shape an individual’s steroid profile is unknown.

Another outstanding question concerns how and when maternal steroids influence the steroid environment experienced by developing offspring because few studies have attempted to link maternal steroids in ovaries or in circulation to steroids in eggs, embryos and/or later in offspring development in fishes28,103,104. Whether steroid content in embryos reflects recent/current maternal history or the mother’s more distant past103,104 is not well understood. There is some evidence that cortisol in fish embryos is reflective of at least several days of past maternal steroid levels and potentially maternal steroids over the entire yolking process (i.e. the exposure of vitellogenic oocytes)103. For example, daily consumption of cortisol-spiked food was detectable in maternal ovaries after 5 days as well as transiently in embryos 3 days later in zebrafish103. Work on field-collected adult females from California stickleback populations suggests that being chased briefly (30 sec per day) by a model predator over the course of ~one month in the laboratory is enough to override past experiences and be detectable in embryo cortisol levels72, and influence offspring behavior74. That being said, it is important to keep in mind that accumulation of steroids in embryos is also not a passive process; in vitro exposure of fish ovarian follicles to elevated cortisol suggests that upregulation of corticosteroid silencing genes protects embryos from excess maternal cortisol103 and embryos themselves can actively remove maternal cortisol from the egg71. It is clear that substantially more work is needed to mechanistically link maternal steroid profiles to those of their eggs, as well as to elucidate the timescale over which maternal experiences are reflected in maternally-derived egg steroid profiles.

Using methodology that allowed us to quantify multiple steroids simultaneously in eggs, we examined for the first time whether the maternally-derived steroids in eggs correspond to predation regime across different populations. Our results emphasize the coordinated and interconnected fashion in which maternally-derived steroids vary within and among steroid classes. Furthermore, our results caution against assuming predation risk is detectable in steroid profiles of eggs in the field. Predator encounters may indeed affect maternal stress and thus, embryonic exposure to maternal steroids, but this pattern is clearly more complex than a simple one-to-one relationship between predation risk at the population level and the multiple steroids mothers deposit in their eggs.

Data availability

Data available from Mendeley Data (McGhee et al. 2020, https://doi.org/10.17632/rngtxkx9y4.1).

References

Creel, S. & Christianson, D. Relationships between direct predation and risk effects. Trends Ecol. Evol. 23, 194–201 (2008).

Creel, S. The control of risk hypothesis: reactive vs. proactive antipredator responses and stress-mediated vs. food-mediated costs of response. Ecol. Lett. 21, 947–956 (2018).

Stuart, Y. E. Divergent uses of “Parallel Evolution” during the history of The American Naturalist. Am. Nat. 193, 11–19 (2019).

Stern, D. L. & Orgogozo, V. Is genetic evolution predictable? Science. 323, 746–751 (2009).

Losos, J. B. Convergence, adaptation, and constraint. Evolution. 65, 1827–1840 (2011).

Bolnick, D. I., Barrett, R. D. H., Oke, K. B., Rennison, D. J. & Stuart, Y. E. (Non) Parallel Evolution. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 49, 303–330 (2018).

Langerhans, R. B. Predicting evolution with generalized models of divergent selection: A case study with poeciliid fish. Integr. Comp. Biol. 50, 1167–1184 (2010).

Foster, S. A. et al. Iterative development and the scope for plasticity: Contrasts among trait categories in an adaptive radiation. Heredity. 115, 335–348 (2015).

O’Steen, S., Cullum, A. J. & Bennett, A. Rapid evolution of escape ability in Trinidad guppies (Poecilia reticulata). Evolution. 56, 776–784 (2002).

Wund, M. A., Baker, J. A., Golub, J. L. & Foster, S. A. The evolution of antipredator behaviour following relaxed and reversed selection in Alaskan threespine stickleback fish. Anim. Behav. 106, 181–189 (2015).

Walsh, M. R. & Post, D. M. The impact of intraspecific variation in a fish predator on the evolution of phenotypic plasticity and investment in sex in Daphnia ambigua. J. Evol. Biol. 25, 80–89 (2012).

Moore, M. P., Riesch, R. & Martin, R. A. The predictability and magnitude of life-history divergence to ecological agents of selection: A meta-analysis in livebearing fishes. Ecol. Lett. 19, 435–442 (2016).

Romero, L. M. Physiological stress in ecology: lessons from biomedical research. Trends Ecol. Evol. 19, 249–255 (2004).

Taff, C. C. & Vitousek, M. N. Endocrine flexibility: optimizing phenotypes in a dynamic world? Trends Ecol. Evol. 31, 476–488 (2016).

Barton, B. A. Stress in Fishes: A diversity of responses with particular reference to changes in circulating corticosteroids. Integr. Comp. Biol. 42, 517–525 (2002).

Bell, A. M., Backström, T., Huntingford, F. A., Pottinger, T. G. & Winberg, S. Variable neuroendocrine responses to ecologically-relevant challenges in sticklebacks. Physiol. Behav. 91, 15–25 (2007).

Cockrem, J. F. & Silverin, B. Sight of a predator can stimulate a corticosterone response in the great tit (Parus major). Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 125, 248–255 (2002).

Sheriff, M. J., Krebs, C. J. & Boonstra, R. The sensitive hare: Sublethal effects of predator stress on reproduction in snowshoe hares. J. Anim. Ecol. 78, 1249–1258 (2009).

Hammerschlag, N. et al. Physiological stress responses to natural variation in predation risk: evidence from white sharks and seals. Ecology 98, 3199–3210 (2017).

Creel, S., Winnie, J. A. J. & Christianson, D. Glucocorticoid stress hormones and the effect of predation risk on elk reproduction. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 106, 12388–12393 (2009).

Fischer, E. K., Harris, R. M., Hofmann, H. A. & Hoke, K. L. Predator exposure alters stress physiology in guppies across timescales. Horm. Behav. 65, 165–172 (2014).

Archard, G. A., Earley, R. L., Hanninen, A. F. & Braithwaite, V. A. Correlated behaviour and stress physiology in fish exposed to different levels of predation pressure. Funct. Ecol. 26, 637–645 (2012).

McCormick, G. L., Robbins, T. R., Cavigelli, S. A. & Langkilde, T. Ancestry trumps experience: Transgenerational but not early life stress affects the adult physiological stress response. Horm. Behav. 87, 115–121 (2017).

Wingfield, J. C. et al. Ecological bases of hormone-behavior interactions: the ‘emergency life history stage’. Am. Zool. 38, 191–206 (1998).

Tilbrook, A. J., Turner, A. I. & Clarke, I. J. Effects of stress on reproduction in non-rodent mammals: the role of glucocorticoids and sex differences. Rev. Reprod. 5, 105–113 (2000).

Payne, A. H. & Hales, D. B. Overview of steroidogenic enzymes in the pathway from cholesterol to active steroid hormones. Endocr. Rev. 25, 947–970 (2004).

Chand, D. & Lovejoy, D. A. Stress and reproduction: Controversies and challenges. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 171, 253–257 (2011).

Leatherland, J. F., Li, M. & Barkataki, S. Stressors, glucocorticoids and ovarian function in teleosts. J. Fish Biol. 76, 86–111 (2010).

Lessells, C. M., Ruuskanen, S. & Schwabl, H. Yolk steroids in great tit Parus major eggs: variation and covariation between hormones and with environmental and parental factors. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 70, 843–856 (2016).

Love, O. P., Mcgowan, P. O. & Sheriff, M. J. Maternal adversity and ecological stressors in natural populations: The role of stress axis programming in individuals, with implications for populations and communities. Funct. Ecol. 27, 81–92 (2013).

Harris, A. & Seckl, J. Glucocorticoids, prenatal stress and the programming of disease. Horm. Behav. 59, 279–289 (2011).

Sheriff, M. J. & Love, O. P. Determining the adaptive potential of maternal stress. Ecol. Lett. 16, 271–280 (2013).

Maccari, S., Krugers, H. J., Morley-Fletcher, S., Szyf, M. & Brunton, P. J. The consequences of early-life adversity: neurobiological, behavioural and epigenetic adaptations. J. Neuroendocrinol. 26, 707–723 (2014).

Henriksen, R., Rettenbacher, S. & Groothuis, T. G. G. Prenatal stress in birds: Pathways, effects, function and perspectives. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 35, 1484–1501 (2011).

Sopinka, N. M., Capelle, P. M., Semeniuk, C. A. D. & Love, O. P. Glucocorticoids in fish eggs: variation, interactions with the environment, and the potential to shape offspring fitness. Physiol. Biochem. Zool. 90, 15–33 (2017).

Moisiadis, V. G. & Matthews, S. G. Glucocorticoids and fetal programming part 2: mechanisms. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 10, 403–11 (2014).

Podmokła, E., Drobniak, S. M. & Rutkowska, J. Chicken or egg? Outcomes of experimental manipulations of maternally transmitted hormones depend on administration method – a meta-analysis. Biol. Rev. 93, 1499–1517 (2018).

Cottrell, E. C., Holmes, M. C., Livingstone, D. E., Kenyon, C. J. & Seckl, J. R. Reconciling the nutritional and glucocorticoid hypotheses of fetal programming. FASEB J. 26, 1866–1874 (2012).

Coslovsky, M., Groothuis, T., de Vries, B. & Richner, H. Maternal steroids in egg yolk as a pathway to translate predation risk to offspring: Experiments with great tits. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 176, 211–214 (2012).

Bell, M. A. & Foster, S. A. Introduction to the evolutionary biology of the threespine stickleback. In The Evolutionary Biology of the Threespine Stickleback (eds. Bell, M. A. & Foster, S. A.) 1–26 (Oxford University Press, 1994).

Peichel, C. L. & Marques, D. A. The genetic and molecular architecture of phenotypic diversity in sticklebacks. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 372 (2017).

Stuart, Y. E. et al. Contrasting effects of environment and genetics generate a continuum of parallel evolution. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 1–7 (2017).

Reznick, D. N., Losos, J. & Travis, J. From low to high gear: there has been a paradigm shift in our understanding of evolution. Ecol. Lett. 22, 233–244 (2019).

Bell, M. A., Aguirre, W. E. & Buck, N. J. Twelve years of contemporary armor evolution in a Threespine Stickleback population. Evolution (N. Y). 58, 814–824 (2004).

Soldin, S. J. & Soldin, O. P. Steroid hormone analysis by tandem mass spectrometry. Clin. Chem. 55, 1061–1066 (2009).

Hill, M. et al. Steroid metabolome in fetal and maternal body fluids in human late pregnancy. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 122, 114–132 (2010).

Adams, D. C. & Collyer, M. L. A general framework for the analysis of phenotypic trajectories in evolutionary studies. Evolution. 63, 1143–1154 (2009).

Oke, K. B., Rolshausen, G., LeBlond, C. & Hendry, A. P. How parallel is parallel evolution? A comparative analysis in fishes. Am. Nat. 190, 1–16 (2017).

Ketha, H., Kaur, S., Grebe, S. K. & Singh, R. J. Clinical applications of LC-MS sex steroid assays: evolution of methodologies in the 21st century. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 21, 217–226 (2014).

Kozlowski, C. P., Bauman, J. E. & Caldwell Hahn, D. A simplified method for extracting androgens from avian egg yolks. Zoo Biol. 28, 137–143 (2009).

Newman, A. E. M. et al. Analysis of steroids in songbird plasma and brain by coupling solid phase extraction to radioimmunoassay. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 155, 503–510 (2008).

Paitz, R. T. & Bowden, R. M. Sulfonation of maternal steroids is a conserved metabolic pathway in vertebrates. Integr. Comp. Biol. 53, 895–901 (2013).

Merrill, L., Chiavacci, S. J., Paitz, R. T. & Benson, T. J. Quantification of 27 yolk steroid hormones in seven shrubland bird species: Interspecific patterns of hormone deposition and links to life history, development, and predation risk. Can. J. Zool. 97, 1–12 (2019).

Oksanen, J. Multivariate analysis of ecological communities in R: vegan tutorial. R Doc. 43, https://doi.org/10.1016/0169-5347(88)90124-3 (2015).

Oksanen, J. et al. vegan: Community Ecology Package (2019).

Revelle, W. psych: Procedures for personality and psychological research (2018).

Kabacoff, R. L. R in action: data analysis and graphics with R. (Manning Publications Co. 2015).

Phillips, P. CPC - Common Principal Component Analysis Program (1999).

Pinheiro, J., Bates, D., DebRoy, S., Sarkar, D. & Team, R. C. nlme: linear and nonlinear mixed effects models (2018).

Kuznetsova, A., Brockhoff, P. & Christensen, R. lmerTest package: tests in linear mixed effects models. J. Stat. Softw. 82, 1–26 (2017).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing (2018).

Wickham, H., François, R., Henry, L. & Müller, K. dplyr: A grammar of data manipulation (2019).

Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant graphics for data analysis (2016).

Ligges, U. & Mächler, M. Scatterplot3d - an R Package for visualizing multivariate data. J. Stat. Softw. 8, 1–20 (2003).

Wright, K. Corrgram: Plot a Correlogram (2018).

Cohen, J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1988).

Arizona Software. GraphClick (2012).

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G. & Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 39, 175–191 (2007).

Paitz, R. T., Mommer, B. C., Suhr, E. & Bell, A. M. Changes in the concentrations of four maternal steroids during embryonic development in the threespined stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus). J. Exp. Zool. Part A Ecol. Genet. Physiol. 323, 422–429 (2015).

Leet, J. K., Gall, H. E. & Sepúlveda, M. S. A review of studies on androgen and estrogen exposure in fish early life stages: effects on gene and hormonal control of sexual differentiation. J. Appl. Toxicol. 31, 379–398 (2011).

Paitz, R. T., Bukhari, S. A. & Bell, A. M. Stickleback embryos use ATP-binding cassette transporters as a buffer against exposure to maternally derived cortisol. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 283 (2016).

Giesing, E. R., Suski, C. D., Warner, R. E. & Bell, A. M. Female sticklebacks transfer information via eggs: effects of maternal experience with predators on offspring. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 278, 1753–1759 (2011).

Roche, D. P. P., McGhee, K. E. E. & Bell, A. M. M. Maternal predator-exposure has lifelong consequences for offspring learning in threespined sticklebacks. Biol. Lett. 8, 932–935 (2012).

McGhee, K. E., Pintor, L. M., Suhr, E. L. & Bell, A. M. Maternal exposure to predation risk decreases offspring antipredator behaviour and survival in threespined stickleback. Funct. Ecol. 26, 932–940 (2012).

Mommer, B. C. & Bell, A. M. A test of maternal programming of offspring stress response to predation risk in threespine sticklebacks. Physiol. Behav. 122, 222–227 (2013).

Mommer, B. C. & Bell, A. M. Maternal experience with predation risk influences genome-wide embryonic gene expression in Threespined Sticklebacks (Gasterosteus aculeatus). PLoS One 9 (2014).

Bonier, F. & Martin, P. R. How can we estimate natural selection on endocrine traits? Lessons from evolutionary biology. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 283 (2016).

Gallagher, A. J. et al. Effects of predator exposure on baseline and stress-induced glucocorticoid hormone concentrations in pumpkinseed Lepomis gibbosus. J. Fish Biol. 95, 969–973 (2019).

Wingfield, J. C. The comparative biology of environmental stress: Behavioural endocrinology and variation in ability to cope with novel, changing environments. Anim. Behav. 85, 1127–1133 (2013).

Jenkins, B. R., Vitousek, M. N., Hubbard, J. K. & Safran, R. J. An experimental analysis of the heritability of variation in glucocorticoid concentrations in a wild avian population. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 281, 20141302 (2014).

Stedman, J. M., Hallinger, K. K., Winkler, D. W. & Vitousek, M. N. Heritable variation in circulating glucocorticoids and endocrine flexibility in a free-living songbird. J. Evol. Biol. 30, 1724–1735 (2017).

Patterson, S. H., Hahn, T. P., Cornelius, J. M. & Breuner, C. W. Natural selection and glucocorticoid physiology. J. Evol. Biol. 27, 259–274 (2014).

Langerhans, R. B., Gifford, M. E. & Joseph, E. O. Ecological speciation in Gambusia fishes. Evolution. 61, 2056–2074 (2007).

Langerhans, R. B. Predictability and parallelism of multitrait adaptation. J. Hered. 109, 59–70 (2018).

Grissom, N. & Bhatnagar, S. Habituation to repeated stress: Get used to it. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 92, 215–224 (2009).

Walsh, M. R. et al. Local adaptation in transgenerational responses to predators. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 283 (2016).

Lyons, D. M. & Parker, K. J. Stress inoculation-induced indications of resilience in monkeys. J. Trauma. Stress 20, 423–433 (2007).

Cyr, N. E. & Romero, L. M. Chronic stress in free-living European starlings reduces corticosterone concentrations and reproductive success. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 151, 82–89 (2007).

Conover, D. & Schultz, E. T. Significance of countergradient variation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 10, 248–252 (1995).

Wainwright, P. C. Many-to-one mapping of form to function: A general principle in organismal design? Integr. Comp. Biol. 45, 256 (2005).

Manceau, M., Domingues, V. S., Linnen, C. R., Rosenblum, E. B. & Hoekstra, H. E. Convergence in pigmentation at multiple levels: Mutations, genes and function. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 365, 2439–2450 (2010).

Elmer, K. R. et al. Parallel evolution of Nicaraguan crater lake cichlid fishes via non-parallel routes. Nat. Commun. 5, 1–8 (2014).

Agrawal, A. A. Toward a predictive framework for convergent evolution: integrating natural history, genetic mechanisms, and consequences for the diversity of life. Am. Nat. 190, S1–S12 (2017).

Thompson, C. J. et al. Many-to-one form-to-function mapping weakens parallel morphological evolution. Evolution. 71, 2738–2749 (2017).

Miller, S. E., Roesti, M. & Schluter, D. A single interacting species leads to widepsread parallel evolution of the stickleback genome. Curr. Biol. 29, 1–8 (2019).

Cohen, A. A., Martin, L. B., Wingfield, J. C., McWilliams, S. R. & Dunne, J. A. Physiological regulatory networks: ecological roles and evolutionary constraints. Trends Ecol. Evol. 27, 428–435 (2012).

McGlothlin, J. W. & Ketterson, E. D. Hormone-mediated suites as adaptations and evolutionary constraints. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 363, 1611–1620 (2008).

Bourg, S., Jacob, L., Menu, F. & Rajon, E. Hormonal pleiotropy and the evolution of allocation trade-offs. Evolution. 73, 661–674 (2019).

Clinchy, M., Sheriff, M. J. & Zanette, L. Y. Predator-induced stress and the ecology of fear. Funct. Ecol. 27, 56–65 (2013).

Creel, S., Dantzer, B., Goymann, W. & Rubenstein, D. R. The ecology of stress: Effects of the social environment. Funct. Ecol. 27, 66–80 (2013).

Miles, M. C. et al. Standing variation and the capacity for change: Are endocrine phenotypes more variable than other traits? Integr. Comp. Biol. 58, 751–762 (2018).

Taff, C. C., Schoenle, L. A. & Vitousek, M. N. The repeatability of glucocorticoids: A review and meta-analysis. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 260, 136–145 (2018).

Faught, E., Best, C. & Vijayan, M. M. Maternal stress-associated cortisol stimulation may protect embryos from cortisol excess in zebrafish. R. Soc. 3, 1–9 (2016).

Kleppe, L. et al. Cortisol treatment of prespawning female cod affects cytogenesis related factors in eggs and embryos. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 189, 84–95 (2013).

Clinchy, M. et al. Multiple measures elucidate glucocorticoid responses to environmental variation in predation threat. Oecologia 166, 607–614 (2011).

Boonstra, R., Hik, D., Singleton, G. R. & Tinnikov, A. The impact of predator-induced stress on the snowshoe hare cycle. Ecol. Monogr. 68, 371–394 (1998).

Clinchy, M., Zanette, L., Boonstra, R., Wingfield, J. C. & Smith, J. N. M. Balancing food and predator pressure induces chronic stress in songbirds. Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 271, 2473–2479 (2004).

Graham, S. P., Freidenfelds, N. A., McCormick, G. L. & Langkilde, T. The impacts of invaders: Basal and acute stress glucocorticoid profiles and immune function in native lizards threatened by invasive ants. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 176, 400–408 (2012).

Hik, D. S., McColl, C. J. & Boonstra, R. Why are Arctic ground squirrels more stressed in the boreal forest than in alpine meadows? Ecoscience 8, 275–288 (2001).

Scheuerlein, A., Van’t Hof, T. J. & Gwinner, E. Predators as stressors? Physiological and reproductive consequences of predation risk in tropical stonechats (Saxicola torquata axillaris). Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 268, 1575–1582 (2001).

Sheriff, M. J. et al. The ghosts of predators past: population cycles and the role of maternal programming under fluctuating predation risk. Ecology 91, 2983–2994 (2010).

Acknowledgements

We thank past Alaskan field crews and Zhong Li at the Metabolomics Center, University of Illinois. We thank Hank Stevens for feedback and patient advice on our adonis R-code, as well as Mike McCoy and Sarah Friedrich for statistical advice and two reviewers for comments that improved the manuscript. Funding was provided by NSF IOS 1121980 to K.E.M and A.M.B., and NIH PHS 1 R01 GM082937 to A.M.B. and M. Band.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

K.E.M. and A.M.B. conceived the study with input from all authors; J.A.B. and S.A.F. provided guidance in the field and knowledge of the predation history of each population; R.T.P. collected the samples and extracted the steroids; K.E.M. analyzed the data; K.E.M. and R.T.P. wrote the manuscript with feedback from all authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

McGhee, K.E., Paitz, R.T., Baker, J.A. et al. Effects of predation risk on egg steroid profiles across multiple populations of threespine stickleback. Sci Rep 10, 5239 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-61412-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-61412-5

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.