Abstract

Intertrochanteric fractures (ITFs) in the elderly are still a big challenge for clinical doctors. Although proximal femoral nail antirotation (PFNA) and bipolar hemiarthroplasty (BPH) are selected by most of the orthopaedic surgeons for elderly ITFs patients, there is still no consensus on the superiority of PFNA and BPH for ITFs in elderly. In this study, we hypothesized that BPH should not be selected as the primary option for ITFs in elderly patients, and analyzed clinical data of 202 elderly ITFs patients aged 80 years or more treated with PFNA (Group A) and BPH (Group B) to compare the early outcome of PFNA and BPH for ITFs in elderly patients aged 80 years or more. We found that operation time and blood loss during surgery in group A are less than in Group B. Time of weight bearing after operation in Group A is longer than in Group B. Incidence of complications 2 weeks after operation in Group A is 9.29% less than 25.81% in Group B (χ2 = 9.539, p = 0.002). Mortality rates 12 months after operation in Group A is 11.43% similar with 19.35% in Group B (χ2 = 2.261, p = 0.133). Harris Hip Score 12 months after operation in Group A is 68.00 ± 29.11 points similar with 65.73 ± 33.29 points in Group B (t = 0.490, p = 0.625). Therefore, for elderly ITFs patients aged 80 years or more, BPH should not be selected as the primary option for ITFs in elderly patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Intertrochanteric fractures (ITFs), commonly occurred in the elderly, are still a big challenge for orthopaedic surgeons due to the multitude of co-morbidities and high 1-year mortality rate associated with them1,2. In order to reduce disability and mortality rate, early surgical procedure, which allows early mobilization, restores the function of the limb, has become the general consensus for the ITFs treatment in the literature3. Different from the various operation methods for young ITFs patients (Dynamic hip screws (DHS), Medoff sliding plate (MSP), Percutaneous compression plating (PCCP), Less invasive stabilization system (LISS), Gamma nail and PFNA), PFNA and BPH are now the two main methods used by surgeons for ITFs in the elderly4,5. However, until now, there is still no consensus on the superiority of PFNA and BPH for the elderly ITFs patients6. As a result, we decide to explore which one (PFNA or BPH) is better for the elderly ITFs patients especially those aged 80 years or more.

Materials and Methods

Subjects

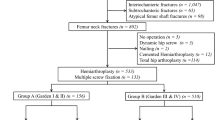

This retrospective study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhengzhou Central Hospital and performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. Clinical data of 202 ITFs elderly patients (≥80 years old) treated with PFNA and BPH within 3 weeks after injury from department of Orthopedics in Henan Provincial People’s Hospital, Zhengzhou Orthopedics Hospital, and Zhengzhou Central from January 1st 2017 to July 31th 2018 were retrospectively analyzed. Exclusion criterion includes: patients with 1, pathologic fractures; 2, concomitant pelvic fracture; 3, fractures associated with polytrauma; 4, immobility or walking difficulties before fracture; 5, infection in the hip or pelvic area or sepsis; 6, preexisting ipsilateral femoral implant; 7, mental illness or acute confusion without a history of dementia; 8, preoperative ASA physical status: grade IV; 9, duration of follow-up less than 12 months; 10, malignant tumors. Flow chart of patients in this study is shown in Fig. 1.

Patients enrolled in this study were grouped as follows: Group A: 140 patients treated with PFNA; Group B: 62 patients treated with BPH. Record gender, age, period of follow-up, fracture classification(according to Evans-Jensen), preoperative ASA physical status, interval between injury and operation, method of anaesthesia, duration of operation time, blood loss during surgery, time of weight bearing after operation, incidence of complications 2 weeks after operation, mortality rates and Harris Hip Score 12 months after operation.

Surgical techniques

Operations were performed under spinal anaesthesia or general anaesthesia.

BPH was performed through lateral approach with the patient in a lateral decubitus position and the affected hip was uppermost. First, fracture fragments including the femoral head, neck, calcar (posteromedial fragment) and lesser trochanter were removed; Second, femoral canal was prepared using a broach and a Wagner SL cementless distal fixation femoral stem (Zimmer, USA) was inserted into the femoral canal; Third, displaced greater trochanter fracture fragments were reduced and fixed by wire as a ‘8’ shape; Fourth, trial reduction was performed and appropriate neck length and bipolar head diameter were selected; Fifth, reattach the capsule and close the wound in layers.

PFNA (Synthes; USA) was performed on traction tables in a supine position under C-arm fluoroscopy. First, perform the closed reduction of the fracture fragments; Second, insert the nail from the lateral aspect of the greater trochanter; Third, insert the column screw until its tip as close as 5 mm to the subchondral bone; Forth, fix the locking bolt and the end cap; Seventh, close the wound in layers.

Peri-operative protocol

Antibiotic prophylaxis was used within 30–60 min before incision and within the first 24 h postoperatively in the two groups. Low molecular weight heparin was used daily and continued until check out. Aspirin was used after checking out for another one month.

For the BPH group, patients were permitted weight bear standing in the first week after surgery depending on the physical status of the patients and encouraged to use a walker until the patients had adequate muscle strength and balance. Excessive hip flexion (>90°) and adduction were not allowed within the first six weeks after surgery.

For the PFNA group, patients were encouraged to sit halfway and exercise lower extremities in bed on the first day after operation. Time of weight bearing standing was decided depending on the reduction of bone structures and the position of the fixation.

Patients were followed up at 6 weeks, 3 months, half an year, 1 year, and annually thereafter for clinical and radiological examinations. If the patient can’t come to our department personally, the clinical outcomes were evaluated by telephone, and the radiological outcomes were evaluated by X-ray films which obtained at their local hospitals.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, and counting data are presented as percentage. t-test was used for the comparison of measurement data, while Chi-square test (χ2) was used to compare the counting data among groups. P value less than 0.05 was considered as significant difference. All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 19, IBM SPSS Software).

Results

Comparison of basic clinical data between the two groups before operation

A total of 214 ITFs patients were reviewed, 12 patients were excluded for there were three pathologic fractures, three patients with walking difficulties before fracture, two fractures associated with polytrauma and four patients were lost due to failed followed up. Finally, 202 patients were followed up successfully. Patient demographics are presented in Fig. 1. As shown in Table 1, there were no significant differences between the groups in terms of gender, age, fracture classification according to Evans- Jensen, follow-up duration, pre-operative ASA physical status classification, method of anaesthesia and interval between injury and operation.

Comparison of operative statistics between the two groups

When compare operative statistics (Table 2) such as duration of operation time (103.47 ± 41.09 min in Group A and 119.26 ± 32.32 min in Group B), blood loss during surgery (71.50 ± 26.09 ml in Group A and 187.90 ± 98.22 ml in Group B) between patients from the two groups, the difference are significant.

Comparison of postoperative data between the two groups

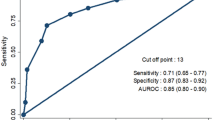

When compare the postoperative data such as time of weight bearing after operation (47.96 ± 31.16 days in Group A is longer than 10.68 ± 21.36 days in Group B), incidence of bad complications 2 weeks after operation (Table 3), 13 patients (9.29%) in Group A is much less than 16 patients (25.81%) in Group B, the difference are significant. However, functional outcome (Harris Hip Score 12 months after operation) in Group A (68.00 ± 29.11 points) is similar with Group B (65.73 ± 33.29 points), and mortality rates 12 months after operation in Group A is 11.43% similar with 19.35% in Group B, the difference are not significant.

Discussion

Due to the aging of the population and rapid development of society, the number of elderly patients with ITFs is increasing year by year. Open or closed reduction with internal fixation has been accepted as effective treatments for this injury7. An ideal surgical technique for elderly ITFs patients should have the least intra and post operative morbidity8. Although proximal femoral nail antirotation (PFNA) has been selected by most surgeons for elderly ITFs patients9,10,11, failures of PFNA have also been reported due to extensive comminution, osteoporosis or long bedridden duration11. As a result, BPH, which permits early full-weight bearing, avoids the failures of osteosynthesis, was first used in 1978 and subsequently used by other surgeons for ITFs treatment with satisfied results12, and has been suggested as an alternative method for elderly ITFs patients5,13. Unfortunately, researchers also found that BPH brings much more surgical injury than PFNA to patients due to the longer operation time and much more blood loss, and recommended that BPH should be undertaken with caution in carefully selected patients14,15. However, it is still unclear whether BPH or PFNA is the better choice for elderly ITFs patients. In this study, we found that although BPH and PFNA have similar functional outcome and mortality rates 12 months after operation, BPH has more postoperative complications in elderly patients with ITFs, BPH is not a good primary treatment for TIFs in elderly patients.

The goals of treatment of ITFs in the elderly are to regain preoperative ambulatory status with the lowest rate of medical and surgical complications16. Similar with published data14, in this study, we also find that PFNA and BPH have similar functional outcome, which means in the term of functional recovery, either PFNA or BPH is accepted for elderly ITFs patients. Consistent with previous results17,18, we also found that PFNA has shorter duration of operation time and less blood loss during surgery than BPH, which implies that PFNA does less surgical injury to patients. However, different from the hypothesis that longer bed-ridden (time of weight bearing after operation in Group A is 47.96 ± 31.16 days longer than 10.68 ± 21.36 days in Group B) leads to a high rate of general complications, our data demonstrated that incidence of bad complications two weeks after operation in Group A is much lower than Group B. For this phenomenon, we think there are at least three reasons, first, for the elderly patients underwent surgical treatment, surgical treatment itself is the second trauma to the patients, so less surgical trauma (PFNA) will bring less post-operative complications. Second, although the time of weight bearing after operation in Group A is much longer than in Group B, patients in Group A could exercise their lower extremities and sit halfway in bed on the first day after operation, which is totally different from the preoperatively unable to exercise due to pain. Third, although patients in Group B have early time of weight bearing after operation, due to the physical and psychological injury by the fracture, they dare not exercise as young patients to avoid falling down again and just stand around the bed, flex and extend knee and hip joints mildly. So, to some extent, the benefit of “early exercise” in Group B is similar with “bed-ridden exercise” in Group A.

Although PFNA does less surgical injury to patients, there are no significant difference when compare the mortality rates between patients from the two groups 12 months after operation. The underlying reason may be that only elderly ITFs patients aged 80 years or more were included (mean age was 86.10 years in our study), whose remaining life expectancy is short even though they do not suffer from the ITFs and PFNA or BPH.

Overall, in this study, we found that although BPH and PFNA have similar functional outcome and mortality rates 12 months after operation, BPH has more postoperative complications in elderly patients with ITFs, BPH is not a good primary treatment for TIFs in elderly patients. But there are some limitations in this study, first, our study was a retrospective controlled study, although the patient groups appeared similar, patients were not randomly assigned to the groups. Second, the duration of follow-up is short. However, a long-term follow-up has little clinical relevance considering the remaining life expectancy.

References

Xue, D. et al. The treatment strategies of intertrochanteric fractures nonunion: An experience of 23 nonunion patients. Injury 48, 708–714, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2017.01.042 (2017).

Ucpunar, H. et al. Comparative evaluation of postoperative health status and functional outcome in patients treated with either proximal femoral nail or hemiarthroplasty for unstable intertrochanteric fracture. J. Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 27, 2309499019864426, https://doi.org/10.1177/2309499019864426 (2019).

Yu, J. et al. Internal fixation treatments for intertrochanteric fracture: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized evidence. Sci Rep 5, 18195, https://doi.org/10.1038/srep18195 (2015).

Arirachakaran, A. et al. Comparative outcome of PFNA, Gamma nails, PCCP, Medoff plate, LISS and dynamic hip screws for fixation in elderly trochanteric fractures: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur. J. Orthop. Surg. Traumatol 27, 937–952, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00590-017-1964-2 (2017).

Tang, P., Hu, F., Shen, J., Zhang, L. & Zhang, L. Proximal femoral nail antirotation versus hemiarthroplasty: a study for the treatment of intertrochanteric fractures. Injury 43, 876–881, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2011.11.008 (2012).

Nie, B., Wu, D., Yang, Z. & Liu, Q. Comparison of intramedullary fixation and arthroplasty for the treatment of intertrochanteric hip fractures in the elderly: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 96, e7446, https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000007446 (2017).

Chandak, R. et al. Description of new “epsilon sign” and its significance in reduction in highly unstable variant of intertrochanteric fracture. Eur. J. Orthop. Surg. Traumatol, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00590-019-02478-4 (2019).

Ong, J. C. Y., Gill, J. R. & Parker, M. J. Mobility after intertrochanteric hip fracture fixation with either a sliding hip screw or a cephalomedullary nail: Sub group analysis of a randomised trial of 1000 patients. Injury, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2019.06.015 (2019).

Dehghan, N. & McKee, M. D. What’s New in Orthopaedic Trauma. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am 100, 1158–1164, https://doi.org/10.2106/JBJS.18.00292 (2018).

Maroun, G. et al. High comorbidity index is not associated with high morbidity and mortality when employing constrained arthroplasty as a primary treatment for intertrochanteric fractures in elderly patients. Eur. J. Orthop. Surg. Traumatol 29, 1009–1015, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00590-019-02394-7 (2019).

Socci, A. R., Casemyr, N. E., Leslie, M. P. & Baumgaertner, M. R. Implant options for the treatment of intertrochanteric fractures of the hip: rationale, evidence, and recommendations. Bone Joint J 99-B, 128–133, https://doi.org/10.1302/0301-620X.99B1.BJJ-2016-0134.R1 (2017).

Green, S., Moore, T. & Proano, F. Bipolar prosthetic replacement for the management of unstable intertrochanteric hip fractures in the elderly. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res., 169–177 (1987).

Fahad, S., Nawaz Khan, M. Z., Khattak, M. J., Umer, M. & Hashmi, P. Primary Proximal femur replacement for unstable osteoporotic intertrochanteric and subtrochanteric fractures in the elderly: A retrospective case series. Ann Med. Surg. (Lond) 44, 94–97, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amsu.2019.07.014 (2019).

Esen, E., Dur, H., Ataoglu, M. B., Ayanoglu, T. & Turanli, S. Evaluation of proximal femoral nail-antirotation and cemented, bipolar hemiarthroplasty with calcar replacement in treatment of intertrochanteric femoral fractures in terms of mortality and morbidity ratios. Eklem Hastalik Cerrahisi 28, 35–40, https://doi.org/10.5606/ehc.2017.53247 (2017).

Kumar, P., Rajnish, R. K., Sharma, S. & Dhillon, M. S. Proximal femoral nailing is superior to hemiarthroplasty in AO/OTA A2 and A3 intertrochanteric femur fractures in the elderly: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Int. Orthop, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00264-019-04351-9 (2019).

Zhao, F., Wang, X., Dou, Y., Wang, H. & Zhang, Y. Analysis of risk factors for perioperative mortality in elderly patients with intertrochanteric fracture. Eur. J. Orthop. Surg. Traumatol 29, 59–63, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00590-018-2285-9 (2019).

Yoo, J. I. et al. Early Rehabilitation in Elderly after Arthroplasty versus Internal Fixation for Unstable Intertrochanteric Fractures of Femur: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Korean Med. Sci. 32, 858–867, https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2017.32.5.858 (2017).

Jia, L. et al. Proximal femoral nail antirotation internal fixation in treating intertrochanteric femoral fractures of elderly subjects. J. Biol. Regul Homeost Agents 31, 329–33 (2017).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.C.H., Y.X.S. and W.Y.P. participated in the design of the study and the acquisition and interpretation of data, performed the statistical analysis, and drafted the manuscript. Z.W., Y.H.D., Y.B. and A.G.W. participated in the acquisition and interpretation of data and helped to draft the manuscript. Y.Q.Z., J.Z. and H.K.L. and participated in the design of the study, and helped to statistical analysis and to draft the manuscript. Y.Q.Z., J.Z. and H.K.L. conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination, helped to statistical analysis and to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, J., Shi, Y., Pan, W. et al. Bipolar Hemiarthroplasty should not be selected as the primary option for intertrochanteric fractures in elderly patients. Sci Rep 10, 4840 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-61387-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-61387-3

This article is cited by

-

Barriers and facilitators of weight bearing after hip fracture surgery among older adults. A scoping review

Osteoporosis International (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.