Abstract

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a major public health threat. Plasmids are able to transfer AMR genes among bacterial isolates. Whole genome sequencing (WGS) is a powerful tool to monitor AMR determinants. However, plasmids are difficult to reconstruct from WGS data. This study aimed to improve the characterization, including the localization of AMR genes using short and long read WGS strategies. We used a genetically modified (GM) Bacillus subtilis isolated as unexpected contamination in a feed additive, and therefore considered unauthorized (RASFF 2014.1249), as a case study. In GM organisms, AMR genes are used as selection markers. Because of the concern of spread of these AMR genes when present on mobile genetic elements, it is crucial to characterize their location. Our approach resulted in an assembly of one chromosome and one plasmid, each with several AMR determinants of which five are against critically important antibiotics. Interestingly, we found several plasmids, containing AMR genes, integrated in the chromosome in a repetitive region of at least 53 kb. Our findings would have been impossible using short reads only. We illustrated the added value of long read sequencing in addressing the challenges of plasmid reconstruction within the context of evaluating the risk of AMR spread.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) genes are naturally present in bacteria, where they function as a defense mechanism. However, the overuse of antibiotics in humans and animals over several decades has led to a rapid rise in the prevalence of AMR genes and the emergence of new AMR mechanisms. The monitoring of AMR is of the utmost importance to have an overview of the circulating resistance genes to implement policies to reduce AMR1,2.

The gold standards for AMR detection are phenotypic susceptibility tests and genotypic (q)PCRs. These methods lack the flexibility to continuously search for new mutations/genes and can be very time-consuming. The revolution in DNA-sequencing technologies, i.e. the so-called whole genome sequencing (WGS) technologies combined with specific databases3, offers a solution as an efficient, high-throughput analysis method for the characterization of AMR genes.

AMR genes can be present on the chromosome or on mobile elements, such as plasmids. Plasmids facilitate the spread of AMR genes, due to their ability to transfer to other bacteria, which is even possible across the species barrier4,5. Despite the importance of plasmids for the monitoring of AMR genes, it has been shown that they are difficult to reconstruct using second generation (i.e. short read) WGS data due to many repeats occurring in the plasmid and that are sometimes even shared with the chromosomal DNA6,7. Therefore, it is difficult to determine the exact location of AMR genes when using short read WGS-based approaches. Nevertheless, this information is needed for a full risk assessment of AMR transmission. The use of long read sequencing such as offered by PacBio and Oxford Nanopore Technology (ONT) would be of added value in this context, as the repetitive regions can be spanned by the long reads generated by this technology8. However, the rather high error rate of ONT9 would benefit from the combination of the long reads with the accuracy of short read sequencing10. This kind of hybrid assembly approach was shown previously to be effective in reconstructing accurate, contiguous genomes, including plasmids containing AMR genes in (pathogenic) wild-type bacteria10,11,12,13.

Although not yet reported to be thoroughly studied in this field, the issue of AMR gene location is especially important in the context of genetically modified microorganisms (GMMs). AMR genes are often used as selection markers for the integration of their newly introduced target genes, needed to produce a specific food or feed additive, such as vitamins, through fermentation or to make them more safe by suppressing the synthesis of toxins14,15,16. Due to technological advances in genetic engineering, it is possible to delete regions from the chromosome or insert foreign DNA. The insertion of genes is done to disrupt the endogenous genes or to more stably express foreign genes. In some cases this is done by plasmids where regions of the plasmid or the entire plasmid are integrated in the chromosome by homologous recombination. However, sometimes it is more beneficial to design plasmids in a way that they remain as an extra-chromosomal element in the bacterial cell without integration of their sequences. So, both scenarios are possible, i.e. plasmid DNA extra-chromosomally present or integrated in the chromosome of the GMM.

There exists a complex regulatory framework for the placement of GMMs or derived products and substances in the European market. Producer companies of GMMs used in the food chain or as producer organisms for substances of interest should submit an application to the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) for safety evaluation, covering the characterization of the microorganisms used as producer organism, to get authorization for the marketing of their products. Recently, in the guidance of EFSA on the characterization of GMMs14, there is a newly introduced section that focuses on the fact that GMMs should not contribute to the pool of resistance against antimicrobials that are clinically relevant for their use in humans and animals. To protect consumers against potential adverse effects, viable GMMs should be absent in the microbial fermentation products commercialized on the European (EU) market (EC/1831/2003, EC/1332/2008, EC/1333/2008, EC/1334/2008)17,18,19,20. Moreover, if a contamination of a GMM is present in e.g. vitamins commercialized on the EU market, they are consequently falling under EU regulations related to the commercialization of genetically modified food and feed (2001/18/EC; 1829/2003/EC; 1830/18/2003)21,22,23. As there is no dossier submitted to EU for this use in the context of these regulations, this GMM is per se unauthorized and zero tolerance, including for its associated recombinant DNA, must be applied. Besides this regulatory aspect, AMR gene transmission also poses health and environmental concerns. The presence of full AMR genes in food/feed additives cannot only lead to direct transmission along the food chain to pathogens, but AMR genes can also spread to environmental reservoirs24,25,26.

Therefore, enforcement laboratories are starting to be involved in the official control of these GMM-derived products, to detect unexpected contaminations which make the GMM unauthorized. However, this detection is not an easy task as the dossier filed to EFSA containing the sequence information is confidential. Therefore, the information to develop the necessary qPCR methods targeting the specific GM events is not readily available27. Also because, unlike for plant GMOs, the companies do not have to provide any information to trace this GMO in the food and feed chains. Therefore, whole genome sequencing (WGS) becomes one of the major tools available to enforcement laboratories to characterize a GMM.

In 2014, a living GM Bacillus subtilis was detected in a feed additive that was capable of overproducing riboflavin (vitamin B2). Therefore, this GMM was unauthorized and consequently, a European Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed (RASFF) notification was created to alert other European countries (code 2014.1249). This GMM was imported from China and was distributed to up to 11 European countries. In 2015, the GM Bacillus strain (isolate 2014-3557) was isolated and WGS was applied (Illumina HiSeq2500, 2 × 125 bp) which was used to develop a qPCR method to quickly detect this GMM in other feed additives27,28. In an attempt to further characterize the strain, the genome of the same isolate was sequenced in 2017 (with Illumina MiSeq2 × 150 bp, HiSeq2 × 50 bp and GS junior System 400–600 bp) by two German enforcement laboratories29. These reads were used for the assembly of 4 GM plasmids (called pGMsub01–04), which contained the aadD (aminoglycoside resistance), blaTEM-116 (beta-lactam resistance), tet(L) (tetracycline resistance) and erm(B) (erythromycin resistance) genes, although pGMsub03 and pGMsub04 were not detected by one of the two labs (‘LHL’). Moreover, in the chromosome, an insertion of a cat gene (chloramphenicol resistance) was detected. These AMR genes confer resistance to antibiotics that are determined by the WHO to be clinically relevant for human use30. Furthermore, qPCRs were developed for the detection of the event-specific integration of the cat gene in the chromosome and for the specific detection of the GM plasmids, to be used by the enforcement laboratories. In the supplementary information of the publication29, several claims by the Chinese producer of the GMM were mentioned. However, the claim that there was an integration of five pUC19 plasmids in the chromosome did not correspond with the assemblies presented by the authors29.

Because of these inconsistencies, we hypothesized that as only short read sequencing technologies were used in the assembly of the GM plasmids, the reads might not be able to completely cover the repetitive regions. Therefore, we used the aforementioned unauthorized GMM 2014-3557 as a case study to deliver a proof of concept for a WGS strategy to fully characterize all AMR genes and their exact location. To bridge the gaps of repetitive regions, we used long read sequencing technologies (ONT and PacBio) and a combination of short (MiSeq) and long reads (hybrid assemblies). This approach of hybrid assembly has not yet been reported to be applied on GMMs. Furthermore, we verified the assembly using PCR and qPCR and we determined its phenotype with antibiotic susceptibility and riboflavin dosage tests in comparison to the wild-type B. subtilis.

Results

Characterization of GM B. subtilis 2014-3557 at the genotypic level

In an attempt to better span repetitive regions, we used paired-end MiSeq and ONT MinION reads of the GM B. subtilis DNA to make a de novo hybrid assembly. The total assembly consisted of 2 circular contigs with a total size of 4,279,307 base pairs and a GC% of 43.53. The chromosome (contig 1) is 4,240,660 bp and the plasmid (pGMrib, contig 2) 38,647 bp. Both contigs were determined to be circular (supplementary information, Tables S3 and S4).

In the nucleotide database of NCBI, contig 1 (chromosome) was most similar to the Bacillus subtilis 168 genome (accession number: NZ_CP010052.1) while contig 2 (pGMrib) was most similar to the previously reported pGMsub04 (accession number: LT622643.1)29. Moreover, 99.9% of the de novo assembly aligned to the published scaffolds from Barbau-Piednoir et al.28.

When comparing the chromosomes of the wild-type B. subtilis 168 (NZ_CP010052.1) and the GM 2014-3557 (contig 1) into more detail (Fig. 1), 2 insertions and 5 deletions were found in the GM 2014-3557 genome, in addition to 520 SNPs (supplementary information, Table S6).

Mauve progressive comparison between wild-type B. subtilis 168 (NZ_CP010052.1) and the de novo assembly of the GM B. subtilis 2014-3557. Locally Collinear Blocks (LCBs) are shown in colour and positions where no colour is shown means that there is a deletion (Del) or insertion (Ins) in the GM B. subtilis 2014-3557 compared to the wild-type B. subtilis 168. LCB2 is present in pGMrib of GM B. subtilis 2014-3557 in the opposite orientation. The vertical red lines indicate where a contig begins or ends.

At position 1,744,001 (Fig. 2A), there is a 1,288 bp insertion, i.e. the entire cat gene originating from the plasmid pC19431 is inserted in the recA gene. The recA gene is involved in homologous recombination and DNA repair. At position 2,406,920 a 53 kb insertion occurs (Fig. 2B) within the scpA gene. Within this integration, several occurrences of the full ribDEAHT and partial ribDEA operons were detected. These operons differ from the natural occurring rib operon in B. subtilis and they showed the highest similarity to the rib operon of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens. In addition, multiple copies of beta-lactamase and kanamycin resistance genes were found in the 53 kb insertion. Lastly, a bleomycin resistance gene was found.

Genotypic characterization of the GM B. subtilis 2014-3557. (A) The insertion of the complete chloramphenicol resistance gene (cat) (originating from the plasmid pC19431) interrupting the sequence of the recA gene and the qPCR-558 assay29 that was developed to detect the junction of the cat insertion. (B. The insertion of multiple GM plasmids (pGMsub01 and pGMsub02) inside the chromosome and the PCR assays that were developed in this study to confirm the integration (PCR-longrange-1, PCR-longrange-2, PCR-intp-1 and PCR-intp-2). The integration consists of sequences from pUC19, pUB110, partial and complete rib operons from B. amyloliquefaciens. qPCR primers developed previously29 to detect pGMsub01 and pGMsub02 could bind in this region multiple times (assay 690, 691 and 804). (C). The circular GM plasmid pGMrib, which consists of sequences originating from pLS1, pSM19035, pUC19 and partial and complete rib operons from B. subtilis 168. In yellow and light blue a MauveProgressive comparison of pGMrib to pGMsub03 and pGMsub0429. The qPCR assays developed for the specific detection of the plasmid (qPCR-693, qPCR-69429 and qPCR-vitB2-UGM27) are indicated. Color codes in all panels: Genes in red are associated with riboflavin production, genes in blue are associated with antibiotic resistance, genes in black are all other genes, in light green are (q)PCR amplicons27,29 and in orange are the plasmid sequences inserted in the chromosome.

Upon further inspection of the repetitive insertion at position 2,406,920–2,459,995 we found by using BLAST that it contained 3 repetitions of pGMsub02 (7,581 bp), once pGMsub01 (11,378 bp) and 2 partial sequences of the pGMsub01 plasmid (10,492 bp and 8,467 bp) (Fig. 2B). pGMsub01 and pGMsub02 were previously reported to be extra-chromosomal circular plasmids29, however, in the current de novo assembly, they were present integrated inside the chromosome (contig 1). As described previously29, pGMsub02 is the same as pGMsub01, with the only difference being a deletion of 3,797 bp in the B. amyloliquefaciens rib operon. Moreover, these GM plasmids contain sequences from the partial and complete rib operons of B. amyloliquefaciens (accession number: CP041693.1), pUC19 (accession number: M77789.2) and pUB110 (accession number: M19465.1).

At position 529,007 a region of 20,525 bp was deleted, removing the int (ICEBs1 integrase gene), immA (metallopeptidase gene), immR (HTH-type transcriptional regulator gene), xis (ICEBs1 excisionase gene), nick (putative DNA relaxase gene), rapI (response regulator aspartate phosphatase I gene) and several uncharacterized genes. The second deletion at position 2,461,930 is one of 8,460 bp, and occurs 1,935 bp after the above elaborated insertion of 53 kb. The sequence of ribDEA from the ribDEAHT operon is removed together with a riboflavin switch. Furthermore sipS (signal peptidase I S gene), ypzD (spore germination protein-like protein encoding gene) and ppiB (peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase B gene) were removed from this location. This deletion would make B. subtilis unable to produce riboflavin without additional genetic modifications. However, the full sequence of this deletion can be detected in the extra-chromosomal plasmid of 38 kb (contig 2). At position 3,261,217, there is a third deletion of 200 bp, interrupting a hypothetical protein. At position 3,837,414, a fourth deletion of 106 bp interrupts the sequence of the gene rpoE (DNA-directed RNA polymerase subunit delta). At position 3,921,625, a fifth deletion of 46 bp interrupts the sequence of ywdH (putative aldehyde dehydrogenase gene).

In Fig. 2C the annotation of the pGMrib (contig 2) is visualized. The plasmid contains 1 full ribDEAHT and 1 partial ribAHT operon from B. subtilis. Furthermore, it contains genes that were flanking the rib operon in B. subtilis 168 chromosome, such as scpA and scpB (segregation and condensation genes). The plasmid contains bla (beta-lactamase resistance) from pUC19 plasmid sequences, tet(L) from pLS1 plasmid sequences (accession number: M29725.1) and erm(B) from pSM19035 plasmid sequences (accession number: AY357120.1). BLASTing contig 2 (plasmid) resulted in hits for both the complete pGMsub03 (8,544 bp) and pGMsub04 (29,760 bp), as depicted in Fig. 2C29. However, the part that matched with pGMsub04 was slightly longer and accounted for 30,104 bp.

The annotation of the contigs already revealed some AMR genes. To obtain the full picture of the AMR gene content, we performed a search on the de novo assembly using the ResFinder tool (Table 1). The chromosome (contig 1) contained 6 copies of aadD, 1 copy of aadK, 6 copies of bla-TEM-116, 1 copy of mph(K), 1 copy of cat(pC194) and 1 copy of tet(L) gene, while the plasmid (contig 2) contains 1 copy of erm(B) and 1 copy of a different tet(L) gene. Only the mph(K), aadK and the chromosomal tet(L) genes were naturally present on the B. subtilis 168 chromosome (NZ_CP010052.1). Therefore all other AMR genes were genetically inserted. Amongst the 520 SNPs detected (supplementary information, Table S6), we also found a SNP in the rpsL gene (A > G substitution), which is known to account for streptomycin resistance32.

With PlasmidFinder, the replication origin repS (X64695) was detected at position 5,770–7,260 of contig 2. No plasmid replicon was found in contig 1.

Confirmation of the genetic modifications in GM B. subtilis 2014-3557

As the de novo hybrid assembly of the GM B. subtilis 2014-3557 was different compared to the previously reported characterization29, we performed additional analyses to confirm the integration of the plasmids in the chromosome.

Evidence from sequencing reads

First, a PacBio (sequel) run on the wild-type B. subtilis 168 and the GM B. subtilis 2014-3557 was performed, in an attempt to obtain longer, more accurate reads. However, after comparison to the de novo hybrid assembly (from MiSeq and MinION reads) it was surprisingly found that the latter was more accurate and contiguous (Table S3). This can likely be attributed to the higher average size of the MinION reads (7,731 bp vs. 4,347 bp). Nevertheless, the PacBio reads were useful for further validation of the de novo hybrid assembly. Indeed, the MiSeq, MinION and PacBio reads were mapped to the hybrid assembly to check for coverage and irregularities (insert size, proper pairing of paired end reads and clipping of long reads) in the assembly. The whole assembly was completely covered by the 3 types of reads. Up to 99.9% of the MiSeq and MinION reads and 98.97% of the PacBio reads mapped to the de novo assembly. With long reads (supplementary information, Figures S1 and S2), the entire GM plasmid was covered by uniquely mapped reads. Reads from all three technologies could be uniquely mapped to the insertion sites of the 53 kb repetitive region. However, the average mapping quality in the 53 kb repetitive region was higher for the MinION reads compared to both MiSeq and PacBio reads (supplementary information, Figures S1 and S2). The average depth of uniquely mapped MinION reads in the 53 kb repetitive region (2,406,920–2,459,995) was 74 × (SD 58). As there was not a single read that could span the entire repetitive region, it is possible that this region is longer than 53 kb. However, long MinION and PacBio reads (>12 kbp) were found to cover unique regions in the 53 kb insertion (supplementary information, Table S5).

Evidence from qPCR for the integration of GM plasmids in the chromosome

Next, we investigated the integration of the previously reported plasmids29 in the GM B. subtilis 2014-3557 chromosome using qPCR assays that were previously developed by Paracchini et al.29. The Cq values of two specific qPCR reactions were compared (Table 2) to determine the difference in copy number, i.e. assay 558 (Fig. 2A)29 detecting the integration of the cat gene in the Bacillus chromosome and assay 804 (Fig. 2B)29 detecting the GM plasmid pGMsub02 that is integrated multiple times in the chromosome. Based on an in silico analysis, if the pGMsub01–02 plasmids would be integrated in the chromosome, then assay 804 should produce 4 times more amplicons than assay 558. We obtained for the GM B. subtilis 2014-3557 a Cq difference of 1.89 (SD 0.06) between assay 558 and 804 (Table 2), which indicates a 4-fold copy number difference, assuming that the qPCR efficiency of both assays is 100%. The DNA of the wild-type B. subtilis 168 yielded no detectable amplicon, as expected (Table S2).

Evidence from PCR for the integration of GM plasmids in the chromosome

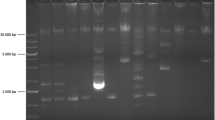

Finally, the integration of the plasmid sequences (pGMsub01 and pGMsub02) in the chromosome, was confirmed using 2 conventional PCRs (PCR-intp-1 and PCR-intp-2, Fig. 2B) targeting the insertion sites. Additionally, long-range PCRs (PCR-longrange-1 and PCR-longrange2, 9 and 10 kb products) that cover regions within the repetitive 53 kb insertion (positions 2,432,562–2,441,949 and 2,451,520–2,461,558) were developed (Fig. 2B). The 4 PCR assays tested positive in the GM B. subtilis 2014-3557 with the expected amplicon size and negative in the B. subtilis 168 (Table 3). Furthermore, a PCR assay (PCR-longrange-3) was developed spanning both the 5′ and 3′ end of the 53 kb integration. This PCR assay only produced an amplicon in the wild-type B. subtilis 168, because the region was too long to be amplified by PCR in the GM B. subtilis (Table 3).

No additional PCRs for the confirmation of the pGMrib were developed as the coverage of the long reads was high and all long reads mapped uniquely in this contig (supplementary information, Figures S1 and S2). This included multiple MinION and PacBio reads of >9 kb that covered the connection between pGMsub03 and pGMsub04, demonstrating that these were indeed part of one plasmid.

Phenotypic characterization of GM B. subtilis 2014-3557

As previously reported27,28,29, a phenotypic difference between wild-type and GM B. subtilis was seen during the culturing step. B. subtilis 2014-3557 displayed a distinctive yellow colour, whereas the wild-type B. subtilis did not show any colour (supplementary information, Fig. S3). As the GM B. subtilis was found to contain a full rib operon (containing essential genes for the production of riboflavin) and riboflavin is known to have a yellow colour, this observation indicated an overproduction of riboflavin by the GM B. subtilis. This was confirmed by the dosage tests of the riboflavin produced by the GM B. subtilis, compared to a wild-type B. subtilis (Table 4).

To investigate at the phenotypic level the AMR pattern of the GM strain, antimicrobial susceptibility profiles were determined and compared to that of the wild-type strain (Table 5). The GM B. subtilis 2014-3557 had acquired phenotypic resistance to clindamycin, chloramphenicol, kanamycin, tetracycline, erythromycin, and streptomycin. This coincides with what we expected based on the genotypic results except for the susceptibility to penicillin.

Discussion

In the current study, we used an unauthorized GM B. subtilis (2014-3557, RASFF 2014.1249) as a case study to deliver a proof of concept for a WGS strategy to fully characterize the present AMR genes and their genomic location. Our approach consisted of the combined use of short and long sequencing reads, complemented with targeted down-stream verification analyses. While this hybrid assembly approach was already successfully applied to wild-type isolates10,11,12,13, it had not been tested yet on GMMs that can be more complex.

We have chosen a GMM as a case study, as AMR genes are being used as selection markers during the engineering process of making the bacterium able to produce specific food and feed additives by fermentation. Often this engineering involves the use of plasmids. Before applications of GMM can be brought to the European market, the microorganism used as producer organism should be characterized and this evaluation should be presented to EFSA for authorization14. Recently, EFSA has highlighted the importance of including data on the full length AMR genes present in the producer strain, and their respective location (chromosome or plasmid)14,15,33. Additionally, the final commercialized food and feed products should be free of producer GM strains (2001/18/EC; 1829/2003/EC; 1830/18/2003)21,22,23. Enforcement laboratories are currently using qPCR methods, targeting short DNA fragments, to detect unexpected contaminations of GMMs in food and feed additives. However, due to the confidentiality of the sequence data of GMMs, it is complicated to develop specific assays. WGS is an open approach contributing to the characterization of unauthorized and/or unknown GMMs, as based on this information, specific qPCRs can be developed27,29. Nevertheless, qPCRs will not allow to detect full-length AMR genes, nor the determination of the location of the AMR gene, while this information is necessary for the risk assessment of the transmissibility of the AMR gene, as stated by EFSA33. If a viable isolate can be retrieved from the food or feed additive, our sequencing strategy would allow full characterization of the GMM, including an overview of full-length AMR genes and their location, to support the official control by the competent authorities, especially in view of the potential risk of AMR spread to the environment and/or consumers. We have chosen this particular GM B. subtilis 2014-3557 as a case study as there have been some previous attempts reported on the characterization of this GMM, including the presence of AMR genes, using short read sequencing27,28,29. One of these studies even indicated the presence of multiple plasmids containing several AMR genes29, making this an interesting yet challenging case study to deliver a proof of concept of our strategy.

We used accurate MiSeq short sequencing reads and backbone-supporting MinION long sequencing reads to perform a de novo hybrid assembly of the GM B. subtilis 2014-3557 genome. In contrast to what was previously reported using solely short sequencing reads27,28,29, where they found 4 plasmids (no published chromosome assembly)29 or were unable to reconstruct the chromosome and plasmid(s) (only contigs reported)27,28, we could assemble the full chromosome of GM B. subtilis 2014-3557 and an extra-chromosomal plasmid of 38 kb. This plasmid contains the entire and a partial ribDEAHT operon originating from B. subtilis, which is deleted in the chromosome. In the chromosome, 5 deletions and 2 insertions have been detected in the current characterization, of which 4 deletions and the cat gene insertion have already been described previously29. The not yet reported insertion consisted of several GM plasmids integrated in the chromosome in a very repetitive structure of at least 53 kb. These plasmids contain partial and full ribDEAHT operons originating from B. amyloliquefaciens. This result could only be obtained based on the combination of short and long read sequencing technologies. The improvement in the characterization of the GM Bacillus compared to previous publications27,28,29, indicates the necessity of hybrid assemblies when analysing genomes with repetitive regions. The genetic modifications facilitate the overproduction of riboflavin and AMR genes were used as markers for selection. There have been some descriptions about GM bacilli overproducing riboflavin in older patents and the scientific literature34,35. However, there was no sequence information available, making it difficult to do a direct comparison between B. subtilis 2014-3557 and earlier reports. Moreover, in the supplementary information of Paracchini et al.29 the claims of the Chinese producer company about the unauthorized GMM are described. Our current assembly of B. subtilis 2014-3557 confirms that genetically modified pUC19 plasmids were inserted into the chromosome. However, there was still a difference in the copy number of the inserted plasmids. The Chinese company claimed to have 5 pUC19 plasmids inserted, however in our de novo assembly up to 6 inserted pUC19 sequences could be detected. Moreover, it was claimed that only the inserted plasmids contained the tetracycline resistance gene. However, in our assembly, this gene was found in the chromosome (inherent to B. subtilis 168 genome) downstream of the 53 kb insertion and a different variant in the extra-chromosomal GM plasmid of 38 kb.

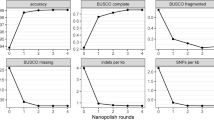

In this study, we have also evaluated assemblies made only with long MinION and PacBio reads (SPAdes36, Canu37, Miniasm38). However, despite the high coverage of the erroneous long reads (10–20% error rate), this resulted in fragmented assemblies and for some AMR genes this also resulted in detection of the incorrect variant. For the PacBio reads, the HGAP4 pipeline gave more accurate and contiguous results, however due to its optimization for the assembly of chromosomes, it was not possible to retrieve the complete pGMrib plasmid sequence, even with additional adjustments. Nevertheless, PacBio sequencing proved useful as extra confirmation for the hybrid assembly made with MiSeq and MinION reads. Additionally, the errors present in long read MinION assemblies can be resolved by the use of accurate short read sequencing.

Despite that the overall structure of our characterization of GM B. subtilis 2014-3557 is different compared to what was previously reported29, similar genes and mutations have been detected in both assemblies. Thus, the qPCR methods that are used by the enforcement laboratories for the detection of this GMM are still valid. However, our assembly shows that some of the primers (assays 690, 691 and 804) that were thought to bind to plasmids actually bind to the chromosome at the location where there is an insertion of these plasmids. This also explains why in the previous characterization29 only pGMsub03 and pGMsub04 were lost in the LHL lab by not culturing them with the appropriate antibiotics. pGMsub01 and pGMsub02 were inserted in the chromosome, thus they were not as easily lost as the 38 kb GM plasmid (which contains sequences from both pGMsub03 and pGMsub04). These qPCR methods are highly needed, as in 2018, there was a new RASFF alert concerning a GM B. subtilis overproducing vitamin B2 found in a feed additive (2018.2755). It is likely that B. subtilis 2018.2755 shares several elements with B. subtilis 2014-3557 such as the rib operon localized in a plasmid and the cat gene insertion based on the qPCRs that tested positive33. However, with all information available it is not possible to determine if it is exactly the same GM B. subtilis strain. Moreover, without the full characterization it is possible that cases are determined as different if a plasmid is lost during culturing or in the environment. If MiSeq reads of the 2018.2755 RASFF alert would be publicly available, it would be possible to do a de novo assembly of this isolate. Then an alignment between the short read assembly of B. subtilis 2018.2755 and our hybrid assembly of B. subtilis 2014-3557 could be made. Based on this alignment it could be determined if new sequences are present. If the latter is the case, additional long read sequencing would be necessary to accurately determine the differences. Additionally, even if the alignment would suggest that B. subtilis 2014-3557 and B. subtilis 2018.2755 are identical, then long read sequencing could be beneficial to elucidate whether there are any duplications or structural rearrangements. Alternatively, based on our assembly, it would be advisable to determine copy number differences of qPCR-558 and qPCR-804 in suspected GM B. subtilis overproducing riboflavin cases. If the Cq difference is much higher or lower than expected, then it would suggest that pGMsub02 is not integrated in the chromosome or integrated with more/less copies. However, with this approach no conclusions can be made about modifications in regions outside the ones targeted by these qPCR assays.

With the de novo hybrid assembly, it was possible to determine the correct variant and the exact location of the AMR genes on the chromosome and plasmid. All detected AMR genes conferred phenotypic resistance except for blaTEM-116. However, in other Bacillus species it has been found that some beta-lactamase genes are not expressed39. Based on the phenotypical data, the GM B. subtilis acquired resistance to erythromycin, kanamycin, and streptomycin that are critically important antibiotics and resistance to chloramphenicol, clindamycin and tetracycline that are highly important antibiotic for human medicine, according to the latest WHO publication30. Even more worrisome is that the genes for tetracycline and erythromycin resistance are present on an extra-chromosomal plasmid, which increases the risk of environmental spread of these AMR genes. With the improved insight into the location of the AMR genes, additional explanation on the observed AMR can be given. Indeed, while both the wild-type and the GM B. subtilis contain the same tet(L) gene in the chromosome, the GM B. subtilis also has a different variant of tet(L) localized on a plasmid that has a higher copy number (3×, as estimated based on the average coverage of MiSeq reads) than the chromosome, which likely contributed to the observed much higher MIC. The increase in MIC to clindamycin and erythromycin can be attributed to the erm(B) gene, while the aadD and cat genes are responsible for the resistance to kanamycin and chloramphenicol, respectively. While aadK confers resistance to streptomycin, this gene is also present in the wild-type B. subtilis 168. Therefore, the streptomycin resistance in GM B. subtilis 2014-3557 can likely be attributed to the chromosomal mutation in the rpsL gene (A > G substitution at position 129,868), which was also found by Paracchini et al.29. The rpsL gene encodes the ribosomal protein S12 and mutations in this gene have been associated with streptomycin resistance32. A bleomycin gene was detected in the GM B. subtilis and while bleomycin is not used in human medicine for antibacterial treatments, it has been shown that this compound, which hinders cell division, has antimicrobial effects towards wild-type B. subtilis that lack this resistance gene40. Moreover, bleomycin has been present in other GMMs41, therefore it is likely used as a selection marker.

In conclusion, in this study we delivered a proof of concept of a WGS strategy to successfully fully reconstruct plasmids and chromosomes, and determine the exact location of the present AMR genes. In our specific case study, our de novo hybrid assembly consisting of MiSeq short sequencing reads and MinION long sequencing reads improved the characterization of an unauthorized GM B. subtilis (RASFF 2014.1249), thereby identifying the presence and genomic location of full AMR genes, many of which are critically important, and other determinants important for the characterization of a GMM, as requested by EFSA14,15,33. For the most complete assembly of the chromosome and plasmid including all correct AMR genes/variants, we indeed recommend to perform hybrid assemblies. To limit the cost, it is advised to apply the WGS strategy stepwise. Thus, first MiSeq sequencing should be performed to detect all unnatural associations, AMR genes and plasmid replicons. Then a de novo assembly created with the MiSeq data should be compared to references42, e.g. the one now provided for GM B. subtilis 2014-3557. If this comparison shows many unnatural associations and/or AMR genes that have not been found before in related GMMs or wild-types, then it is advisable to perform long-read sequencing to fully characterize the GMM isolate. However, duplications and structural rearrangements will likely not be detected with MiSeq reads only. Therefore, for very prevalent and high impact GMM cases it would still be advisable to do additional long read sequencing even if they show high similarity to existing references of GMMs. In our case study we obtained better results with the MinION reads, i.e. longer average read lengths. An additional advantage of the portable MinION flowcells is that they are more accessible for most labs compared to PacBio sequencing.

However, our approach implies that an isolate could be obtained from the food or feed additive. If this were not the case, our strategy would need to be tested and eventually modified to be performed in a metagenomics set-up. The characterization of full AMR genes is not only important in GMM detection and identification14, but it is also of interest for the surveillance of pathogens, usually having a less complex genome. Therefore this study not only contributes to the EFSA demand of better characterization of GMMs, but also to the strategies to be used to strengthen our knowledge and understanding of AMR, one of the five objectives of the Global Action Plan on AMR, launched by the WHO2.

Material and Methods

Bacterial isolates

The bacterial strain used in this study is a GM B. subtilis strain (2014-3557) that was isolated from imported vitamin B2 80% feed additive powder and analysed by the French GMO-Laboratory “Service commun des Laboratoires” in the framework of the Rapid Alert System for Food and Feed (RASFF) 2014.124927,28.

In addition, as a reference, the lab strain B. subtilis 168 (Ehrenber 1835, Cohn1872 AL) was purchased from the Belgian Co-ordinated Collections of Micro-organisms (BCCM) collection.

Bacterial growth, DNA extraction and quality control of DNA

The bacterial strain was first grown on Nutrient agar at 30 °C for 48 to 72 hours with the antibiotic erythromycin. The total DNA of the B. subtilis strain 2014-3557 (genomic and plasmid) was extracted from the pellet of 6 ml of a 48 hour culture grown in Brain-Heart Infusion (BHI) broth at 30 °C with the antibiotic erythromycin, using the Genomic-tip 100/G according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen Benelux B.V., Venlo, the Netherlands). A Nanodrop 2000 device was used to determine the purity of the DNA. The concentration of the DNA was determined with a Qubit 3.0 fluorometer using the Broad range kit (Invitrogen, ThermoFisher Scientific). The 4200 Tapestation with genomic screentapes (Agilent) was used to determine the fragment length of the DNA. The presence of the GM plasmids was confirmed by the qPCRs from Barbau-Piednoir et al. and Paracchini et al.27,29 (supplementary information, Table S2).

Whole genome sequencing

Short read sequencing libraries were prepared with an Illumina Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation Kit and sequenced on an Illumina MiSeq instrument with a 250-bp paired-end protocol (MiSeq v3 chemistry) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Trimming of the short reads was performed with Trimmomatic (version 0.32). First the Illuminaclip option was used to remove the Nextera adapter sequences. Then a sliding window approach of four bases and trimming when the Phred score dropped below 30 was employed. Lastly, the leading and trailing bases of a read were removed when the Phred score dropped below 343. After trimming, this amounted to 920,796 reads with an average Phred-score > 30. These statistics from the reads were extracted with FastQC (version 0.11.7). Based on mapping results, the MiSeq reads amounted to a coverage of 49 × (SD 17) (Fig. S1A).

A long read MinION sequencing library was prepared by using the 1D ligation sequencing kit (SQK-LSK108, Oxford Nanopore) according to the manufacturer’s protocol for genomic DNA (version 6). The optional steps of shearing the DNA to 8 kb fragments with Covaris G tubes and addition of the control DNA (a 3.6 kb fragment of Lambda phage) were included, while the DNA repair was not performed. The sequencing was carried out on a R9.4 flowcell (Oxford Nanopore) and sequenced for 48 hours, which produced 0.25 million reads, a N50 of 9452, average read size of 7,731 bp and a coverage of 343 ×(SD 74) (Fig. S1C). Local basecalling was performed with Guppy (version 3.1.5) (Oxford Nanopore Technologies) with the option enabled to trim the sequencing adapters. Then NanoFilt (version 2.0.0)44 was used to ensure that only the reads with a Phred-score > 7 and a length > 1,000 were used in the de novo assembly. These statistics of the reads and quality scores were extracted with NanoStat (version 0.8.0)44. The control DNA was removed by using the NanoLyse (version 0.5.0) software44.

PacBio sequencing was performed on the wild-type B. subtilis 168 and the genetically modified B. subtilis 2014-3557 with the PacBio Sequel at Baseclear (Leiden, the Netherlands). This run produced 1,649,115 reads with an average size of 4,347 bp and coverage of 1,657 ×(SD 376) (Fig. S1E). These reads were used in the HGAP4 pipeline (SMRTlink version 6.0.0.47841) from PacBio Sequel45,46.

Bioinformatics analysis

De novo hybrid assembly with MiSeq and MinION reads was carried out using Unicycler (version 0.4.8) at default parameters47. The following tools were used in the Unicycler pipeline: SPAdes (version 3.7.1), Miniasm (version 0.3), Racon (version 1.4.3), makeblastdb (version 2.7.1+), tblastn (version 2.7.1+), bowtie2 (version 2.3.4.3), Samtools (version 1.9), java (version 1.8) and Pilon (version 1.22)36,38,48,49,50,51,52. De novo assemblies with other software (SPAdes hybrid, Canu and Miniasm) were performed and corrected with Racon48 and Pilon52. Then circularity of the contigs was determined with Berokka (version 0.2.1)53. However, the de novo assembly obtained from Unicycler was determined to be the most accurate and was used for all subsequent analyses (Table S3). Visualization of the Unicycler assembly was performed in Bandage (version 0.8.1)54 (data not shown). Visualization of the integrated region and plasmids was performed with SeqBuilder (version 10.0.1)55. ResFinder3 was used to determine genes responsible for the genotypic AMR resistance. PlasmidFinder56 was used for the detection of plasmid replicons. BWA-MEM (version 0.7.12-r1039) was used for the mapping of MiSeq reads. Minimap257 was used for mapping the MinION and PacBio reads to the reference genome and hybrid assembly. SAMtools (version 1.9) was used for processing SAM files and extracting mapping statistics51. MauveProgressive (version 2.4.0) was used to compare the reference genome to the de novo assembly58. IGV (version 2.4.4) and Qualimap (version 2.2.1) were used to visualize the mapping, coverage, GC content and the mapping quality59,60. Annotations were performed with Prokka (version 1.13.3)61.

(q)PCR

In each (q)PCR reaction, DNA extracted from the wild-type B. subtilis 168 was used as a negative control. All PCR reactions developed in this study were created by use of the primer-blast software62. This software was also used to test in silico if it was possible to produce any aspecific products in either the GMM or wild-type. For the sequence of all primers, see the supplementary information (Table S1).

The conventional PCRs with amplicons of <1000 bp were performed in a final reaction volume of 25 μl containing 1x DreamTaq Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 300 nM of forward and reverse primer and 5 μl DNA template (1 ng/μl). The PCR cycle program consisted of a denaturation step at 95 °C for 3 minutes, followed by 35 cycles of 30 seconds at 95 °C, 30 seconds at 55 °C and an extension step at 72 °C for 1 minute. At the end, 1 cycle at 72 °C of 15 minutes was performed.

The long range PCRs with amplicon sizes of 9–10 kbp were performed in a final reaction volume of 25 μl containing 1x Master Mix (KAPA readymix), 300 nM of forward and reverse primer and 5 μl DNA template. The PCR cycle program consisted of a denaturation step at 95 °C for 3 minutes, followed by 35 cycles of 30 seconds at 95 °C, 30 seconds at 55 °C and an extension step at 72 °C for 1 minute (+1 minute per kb of amplicon size). At the end, 1 cycle at 72 °C for 1 minutes (+1 minute per kb of amplicon size) was performed.

qPCRs from Barbau-Piednoir et al. and Paracchini et al. were used under the same conditions as described in their respective publications and performed in triplicate using 5 ng template input DNA27,29. A copy number variation analysis between two qPCR reactions was done with the following formula: copy number difference = 2ΔCq.

Antimicrobial susceptibility

The antimicrobial susceptibility profiles (clindamycin, tetracycline, rifampicin, streptomycin, fusidate, penicillin, chloramphenicol, kanamycin, tiamulin, quinupristin/dalfopristin, vancomycin, gentamycin, trimethoprim, erythromycin, ciprofloxacin, cefoxitin, linezolid, mupirocin and sulfamethoxazole) of the GM-Bacillus strain 2014-3557 and the model organism B. subtilis 168 were determined using the microdilution method involving the Sensititre Staphylococci plate – EUST (Veterinary Reference Card, Thermo Scientific). For each of the tested antimicrobials, the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) was determined. The MIC is the lowest concentration of an antimicrobial (in mg/l) that inhibits the visual growth of a micro-organism under the defined in vitro conditions and after a specified time period. There are no MIC values for Bacillus for this antimicrobial available with EUCAST (the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing). Therefore, the MIC values from EFSA were used to determine whether there was phenotypic resistance against the antibiotics that were used63.

Dosage of riboflavin (vitamin B2)

The riboflavin concentration was determined in the supernatant of the GM-B. subtilis strain (2014-3557) and that obtained from wild-type B. subtilis (food origin) using an HPLC method64; Standard (−)-riboflavin (Sigma-Aldrich R7649); Column Lichrospher 60 RP Select B (5 µm) 250 × 4 mm (Merck 1.50984.0001) in column oven Igloo-Cil with column temperature at 30 °C; Isocratic pump Varian prostar 220 at flow rate 0,7 mL/min with mobile phase methanol/sodium acetate 0,05 M buffer 40/60 v/v; Automatic injector Varian prostar 410 with injection volume at 30 µL; Fluorimetric detector Varian prostar 363 at superlow wide mode with λ excitation at 422 nm and λ emission at 522 nm). As blank, BHI culture medium was included. The dosage was performed on the supernatant of 50 ml cultures (centrifuged at 5000 g during 10 min) after 48 hours of growth in BHI medium at 30 °C (Mac Farland 0.8). For each strain, 4 repetitions were included and each supernatant was analysed in duplicate. The blank was analysed only once.

References

Wernli, D. et al. Antimicrobial resistance: The complex challenge of measurement to inform policy and the public. PLOS Med. 14, e1002378 (2017).

World Health Organization. Global action plan on antimicrobial resistance (2015).

Zankari, E. et al. Identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67, 2640–2644 (2012).

Tschäpe, H. The spread of plasmids as a function of bacterial adaptability. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 15, 23–31 (1994).

Thomas, C. M. & Nielsen, K. M. Mechanisms of, and barriers to, horizontal gene transfer between bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3, 711–721 (2005).

Arredondo-Alonso, S., Willems, R. J., van Schaik, W. & Schürch, A. C. On the (im)possibility of reconstructing plasmids from whole-genome short-read sequencing data. Microb. Genomics 3 (2017).

de Toro, M., Garcilláon-Barcia, M. P. & De La Cruz, F. Plasmid Diversity and Adaptation Analyzed by Massive Sequencing of Escherichia coli Plasmids. Microbiol. Spectr. 2 (2014).

Karlsson, E., Lärkeryd, A., Sjödin, A., Forsman, M. & Stenberg, P. Scaffolding of a bacterial genome using MinION nanopore sequencing. Sci. Rep. 5, 11996 (2015).

Tyler, A. D. et al. Evaluation of Oxford Nanopore’s MinION Sequencing Device for Microbial Whole Genome Sequencing Applications. Sci. Rep. 8, 10931 (2018).

Wick, R. R., Judd, L. M., Gorrie, C. L. & Holt, K. E. Completing bacterial genome assemblies with multiplex MinION sequencing. Microb. Genomics 0–6 (2017).

George, S. et al. Resolving plasmid structures in Enterobacteriaceae using the MinION nanopore sequencer: assessment of MinION and MinION/Illumina hybrid data assembly approaches. Microb. Genomics 1–8 (2017).

Sović, I., Križanović, K., Skala, K. & Šikić, M. Evaluation of hybrid and non-hybrid methods for de novo assembly of nanopore reads. Bioinformatics 32, 2582–2589 (2016).

Ashton, P. M. et al. MinION nanopore sequencing identifies the position and structure of a bacterial antibiotic resistance island. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 296–300 (2015).

Rychen, G. et al. Guidance on the characterisation of microorganisms used as feed additives or as production organisms. EFSA J. 16, (2018).

Silano, V. et al. Characterisation of microorganisms used for the production of food enzymes. EFSA J. 17 (2019).

Frey, J. Biological safety concepts of genetically modified live bacterial vaccines. Vaccine 25, 5598–5605 (2007).

EU. Regulation (EC) No 1831/2003 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 September 2003 on additives for use in animal nutrition. Off. J. Eur. Union 29–44 (2003).

EU. Regulation (EC) No 1332/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2008 on food enzymes and amending Council Directive 83/417/EEC, Council Regulation (EC) No 1493/1999, Directive 2000/13/EC, Council Directive 2001/112/EC and Regulat. Off. J. Eur. Union 7–16 (2008).

EU. Regulation (EC) No 1333/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2008 on food additives. Off. J. Eur. Union (2008).

EU. Regulation (EC) No 1334/2008 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 2008 on flavourings and certain food ingredients with flavouring properties for use in and on foods and amending Council Regulation (EEC) No 1601/91, Regulations (EC. Off. J. Eur. Union (2008).

EU. Directive 2001/18/EC of the European Parliament and of the council of 12 March 2001 on the deliberate release into the environment of genetically modified organisms and repealing Council Directive 90/220/EEC. Off. J. Eur. Union (2001).

EU. Regulation (EC) No 1829/2003 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 September 2003 on genetically modified food and feed. Off. J. Eur. Union (2003).

EU. Regulation (EC) No 1830/2003 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 September 2003 concerning the traceability and labelling of genetically modified organisms and the traceability of food and feed products produced from genetically modified o. Off. J. Eur. Union (2003).

Forsberg, K. J., Reyes, A., Wang, B., Selleck, E. M. & Morten, O. a. The shared antibiotic resistome of soil bacteria and human pathogens. 337, 1107–1111 (2014).

Woolhouse, M., Ward, M., van Bunnik, B. & Farrar, J. Antimicrobial resistance in humans, livestock and the wider environment. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 370, 20140083–20140083 (2015).

Davison, J. Genetic Exchange between Bacteria in the Environment. 91, 73–91 (1999).

Barbau-Piednoir, E. et al. Use of next generation sequencing data to develop a qPCR method for specific detection of EU-unauthorized genetically modified Bacillus subtilis overproducing riboflavin. BMC Biotechnol. 15, 103 (2015).

Barbau-Piednoir, E. et al. Genome Sequence of EU-Unauthorized Genetically Modified Bacillus subtilis Strain 2014-3557 Overproducing Riboflavin, Isolated from a Vitamin B2 80% Feed Additive. Genome Announc. 3 (2015).

Paracchini, V. et al. Molecular characterization of an unauthorized genetically modified Bacillus subtilis production strain identified in a vitamin B2 feed additive. Food Chem. 230, 681–689 (2017).

WHO Advisory Group on Integrated Surveillance of Antimicrobial Resistance (AGISAR). Critically Important Antimicrobials for Human Medicine - 6th revision. https://www.who.int/foodsafety/publications/antimicrobials-sixth/en/ (2019).

Horinouchi, S. & Weisblum, B. Nucleotide sequence and functional map of pC194, a plasmid that specifies inducible chloramphenicol resistance. J. Bacteriol. 150, 815–25 (1982).

Inaoka, T., Kasai, K. & Ochi, K. Construction of an In Vivo Nonsense Readthrough Assay System and Functional Analysis of Ribosomal Proteins S12, S4, and S5 in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 183, 4958–4963 (2001).

European Food Safety Authority (EFSA). EFSA statement on the risk posed to humans by a vitamin B2 produced by a genetically modified strain of Bacillus subtilis used as a feed additive. EFSA J. 2019(17), 1–11 (2019).

Mironov, A. S. et al. Method For Producing Riboflavin. WO2004046347A1 (2004).

Stepanov, A. I. & Zhdanov, V. G. Riboflavin prepn. FR2546907A1 (1984).

Bankevich, A. et al. SPAdes: A New Genome Assembly Algorithm and Its Applications to Single-Cell Sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 19, 455–477 (2012).

Koren, S. et al. Canu: scalable and accurate long-read assembly via adaptive k -mer weighting and repeat separation. Genome Res. 27, 722–736 (2017).

Li, H. Minimap and miniasm: fast mapping and de novo assembly for noisy long sequences. Bioinformatics 32, 2103–2110 (2016).

Chen, Y., Succi, J., Tenover, F. C. & Koehler, T. M. Beta-Lactamase Genes of the Penicillin-Susceptible Bacillus anthracis Sterne Strain. J. Bacteriol. 185, 823–830 (2003).

Sikic, B. I., Rozencweig, M. & Carter, S. K. Bleomycin Chemotherapy. (Elsevier (2016).

Scientific Opinion on application EFSA‐GMO‐RX‐MON531 for renewal of the authorisation for continued marketing of existing cottonseed oil, food additives, feed materials and feed additives produced from MON 531 cotton that were notified under Articles 8(1). EFSA J. 9 (2011).

EFSA. Public consultation on the EFSA statement on the requirements for whole genome sequence analysis of microorganisms intentionally used in the food chain. https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/consultations/call/public-consultation-efsa-statement-requirements-whole-genome (2020).

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014).

De Coster, W., D’Hert, S., Schultz, D. T., Cruts, M. & Van Broeckhoven, C. NanoPack: visualizing and processing long-read sequencing data. Bioinformatics 34, 2666–2669 (2018).

Chin, C.-S. et al. Nonhybrid, finished microbial genome assemblies from long-read SMRT sequencing data. Nat. Methods 10, 563–569 (2013).

Koren, S. et al. Reducing assembly complexity of microbial genomes with single-molecule sequencing. Genome Biol. 14, R101 (2013).

Wick, R. R., Judd, L. M., Gorrie, C. L. & Holt, K. E. Unicycler: Resolving bacterial genome assemblies from short and long sequencing reads. PLoS Comput. Biol. 13, 1–22 (2017).

Vaser, R., Sović, I., Nagarajan, N. & Šikić, M. Fast and accurate de novo genome assembly from long uncorrected reads. Genome Res. 27, 737–746 (2017).

Altschul, S. F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E. W. & Lipman, D. J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215, 403–410 (1990).

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359 (2012).

Li, H. et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25, 2078–9 (2009).

Walker, B. J. et al. Pilon: An Integrated Tool for Comprehensive Microbial Variant Detection and Genome Assembly Improvement. PLoS One 9, e112963 (2014).

Seemann, T. B. https://github.com/tseemann/berokka.

Wick, R. R., Schultz, M. B., Zobel, J. & Holt, K. E. Bandage: interactive visualization of de novo genome assemblies: Fig. 1. Bioinformatics 31, 3350–3352 (2015).

DNASTAR. Seqbuilder. https://www.dnastar.com/t-seqbuilder-pro.aspx.

Carattoli, A. et al. In Silico Detection and Typing of Plasmids using PlasmidFinder and Plasmid Multilocus Sequence Typing. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 58, 3895–3903 (2014).

Li, H. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 34, 3094–3100 (2018).

Darling, A., Mau, B. & Blattner, F. R. P. N. Mauve: Multiple Alignment of Conserved Genomic Sequence With Rearrangements. Genome Res. 14, 1394–1403 (2004).

Robinson, J. T. et al. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 24–26 (2011).

García-Alcalde, F. et al. Qualimap: evaluating next-generation sequencing alignment data. Bioinformatics 28, 2678–2679 (2012).

Seemann, T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 30, 2068–2069 (2014).

Ye, J. et al. Primer-BLAST: A tool to design target-specific primers for polymerase chain reaction. BMC Bioinformatics 13, 134 (2012).

EFSA panel on FEEDAP. Guidance on the assessment of bacterial susceptibility to antimicrobials of human and veterinary importance. EFSA J. 10 (2012).

Association Francaise de Normalisation. NF EN 14122: determination of vitamin B2 by high performance liquid chromatography. (2004).

Leinonen, R., Sugawara, H. & Shumway, M. The Sequence Read Archive. Nucleic Acids Res. 39, D19–D21 (2011).

Benson, D., Lipman, D. J. & Ostell, J. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 21, 2963–2965 (1993).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the Ylieff project ‘AMRSeq’ (Belspo). We gratefully acknowledge the technicians of the Transversal activities in Applied Genomics Service at Sciensano for performing the MiSeq sequencing. We would like to thank Stefan Hoffman for his technical assistance with setting up the MinION sequencing experiments, Elodie Barbau-Piednoir for the initial work on the GMM isolate and the Foodborne Pathogens technicians for their laboratory work in determining the phenotypic resistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.R. and S.D.K. conceived and designed this study. S.D.K. supervised the project. B.B. performed the DNA extractions, MinION sequencing and bioinformatics analysis. A.S. provided support for the bioinformatics analysis. K.V. and R.W. were responsible for the bioinformatics infrastructure. B.B. and S.D.K. were responsible for the MiSeq sequencing. C.G-G. was responsible for the MIC tests. P.P. and F.A. were responsible for the riboflavin dosage tests and provided the feed additive. B.B., N.R. and S.D.K. participated in the interpretation of the results. N.R. and K.M. provided specialist feedback on the obtained results. B.B. and S.D.K. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All co-authors commented and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Berbers, B., Saltykova, A., Garcia-Graells, C. et al. Combining short and long read sequencing to characterize antimicrobial resistance genes on plasmids applied to an unauthorized genetically modified Bacillus. Sci Rep 10, 4310 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-61158-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-61158-0

This article is cited by

-

Unraveling metagenomics through long-read sequencing: a comprehensive review

Journal of Translational Medicine (2024)

-

Whole-genome sequence analysis of clinically isolated carbapenem resistant Escherichia coli from Iran

BMC Microbiology (2023)

-

Metagenomics and metabarcoding experimental choices and their impact on microbial community characterization in freshwater recirculating aquaculture systems

Environmental Microbiome (2023)

-

Comparison of 6 DNA extraction methods for isolation of high yield of high molecular weight DNA suitable for shotgun metagenomics Nanopore sequencing to detect bacteria

BMC Genomics (2023)

-

Identification of plasmids in avian-associated Escherichia coli using nanopore and illumina sequencing

BMC Genomics (2023)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.