Abstract

Fungal diseases seriously affect agricultural production and the food industry. Crop protection is usually achieved by synthetic fungicides, therefore more sustainable and innovative technologies are increasingly required. The atmospheric pressure low-temperature plasma is a novel suitable measure. We report on the effect of plasma treatment on phytopathogenic fungi causing quantitative and qualitative losses of products both in the field and postharvest. We focus our attention on the in vitro direct inhibitory effect of non-contact Surface Dielectric Barrier Discharge on conidia germination of Botrytis cinerea, Monilinia fructicola, Aspergillus carbonarius and Alternaria alternata. A few minutes of treatment was required to completely inactivate the fungi on an artificial medium. Morphological analysis of spores by Scanning Electron Microscopy suggests that the main mechanism is plasma etching due to Reactive Oxygen Species or UV radiation. Spectroscopic analysis of plasma generated in humid air gives the hint that the rotational temperature of gas should not play a relevant role being very close to room temperature. In vivo experiments on artificially inoculated cherry fruits demonstrated that inactivation of fungal spores by the direct inhibitory effect of plasma extend their shelf life. Pre-treatment of fruits before inoculation improve the resistance to infections maybe by activating defense responses in plant tissues.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fungal diseases represent one of the main constraints to agriculture and food production, reducing product quantity and quality and causing severe economic losses worldwide. Synthetic fungicides have been largely used as powerful tools for crop protection against many fungal diseases reducing yield losses and contributing to food security. However, their excessive use implicates health and ecological risks and could lead to the selection and spread of resistant strains in fungal pathogens1. Therefore, the implementation of new safer and environmentally friendly solutions in crop protection are encouraged in order to minimize these risks.

Currently, there is an increasing number of undernourished people and worldwide food demand for the steady population growth2. In this context, the integrated use of all the available plant protection measures would play a key role in limiting yield losses caused by plant diseases both in the field as well as in postharvest. Moreover, contamination of food and feeds with toxic substances, including mycotoxins, and human pathogens like Salmonella spp., Listeria monocytogenes, Escherichia coli, and noroviruses represent ongoing challenges for growers and food processors3,4. For these reasons, new sustainable control strategies for plant and food protection are required as a valid eco-friendly possibility for improving the safety and quality of food products and reducing the impact on the environment.

Innovative technologies, based on sustainability, human safety, and long-term eco-safety, has been recently promoted and investigated. Among those, the atmospheric pressure low temperature plasma (LTP) represents a novel promising tool5. LTPs can be produced with different discharge configurations, such as corona, micro-hollow cathode, gliding arc, atmospheric uniform glow, dielectric barrier discharges, plasma jet and needle6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14.

The composition and efficacy of LTP is related to the device and system operating parameters (gas mixture, flow rate, humidity, temperature, voltage and frequency)15,16,17. Atmospheric air LTP is a mixture of electrons, ions, radicals, stable reaction products, excited atoms and molecules, and ultraviolet radiation (UV) known for their antimicrobial properties18. The species produced by air plasma sources are electronically and vibrationally excited molecules (O2 and N2), reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (ROS and RNS)6. In general ROS species trigger an oxidative stress response leading to detrimental oxidative cell damage19,20 and consequently to the inactivation of microorganisms13,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30. Hydroxyl radicals (OH) have a direct impact on the cell membranes of microorganisms, made of a bilayer of glycerophospholipids and proteins, that are susceptible to their attacks31,32.

In the last two decades, extensive multidisciplinary research has been carried out proving the validity of the plasma technology application in the broad field of biology and health care6,33,34,35,36, dental care37,38,39, skin diseases40, chronic wounds41, cosmetics42,43 and antimicrobial clinical treatments against various pathogens44. As for plasma medicine, interest has grown in recent years on the application of plasma to agriculture, with an increasing number of uses for the treatment of crops, seeds, water and soil, and at multiple steps in the food industry. On seeds, LTP treatment reduces microbial contamination and promotes germination, rooting and growth of seedlings45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53. It has enhanced safety while maintaining quality properties of a wide range of perishable food products in a fast processing time54. LTP is a promising tool for the inactivation of microbial contaminants55, including foodborne pathogens56, and preservation of perishable food products. It has a great potential for industrial applications due to its non-thermal operation, short processing time, energy efficiency, and antimicrobial efficacy with minimal impact on food quality and the environment57,58.

The characteristics of target microorganisms play an important role in achieving successful decontamination with plasma treatment. Current LTP technology has significantly reduced the microbial load in in vitro tests on bacteria up to a 1 million factor in a few seconds. We can expect differences in sensitivity among microorganisms related to their intrinsic differences in cytology, morphology, reproductive cycles, and growth59. However, unlike conventional antimicrobial agents, plasma is expected to further activate the natural host defences, giving an additional chance to avoid the threat of pathogen infection60.

The duration of treatment and power supply for plasma generation are extremely important parameters that could affect the efficacy of the treatment57. Careful selection of such parameters must be performed in order to act only on microorganisms without affecting produce commercial value.

In the present paper, we report on the effects of plasma treatment on important fungal plant pathogens, Botrytis cinerea, Monilinia fructicola, Aspergillus carbonarius and Alternaria alternata, causing quantitative and qualitative losses of agricultural production both in the field and post-harvest. We focused our attention on the direct inhibitory effects of Surface Dielectric Barrier Discharge (SDBD) on spore germination of the four fungi. Different diagnostic techniques have been herein used in an attempt to understand the pathway responsible for the observed inhibitory effect. The first application of plasma treatment was also carried out on cherry fruit, in order to promote a possible application of the developed method in agricultural practice.

Results

Discharge system

The SDBD operated at atmospheric pressure in humid ambient air (25 °C, 40% RH). The driving AC-voltage (8.6 kVpp (peak-to-peak), see Fig. 1) was a burst of two AC cycles (fAC = 5 kHz) with a repetition rate of 500 Hz (duty cycle of 0.2) ensuring a homogenous distribution of microdischarges. The real discharge ‘ON’ period is actually shorter compared with the AC cycle period, we can estimate an effective duty cycle of the order of 0.1 of the nominal one53. This guarantees that the biological samples were not exposed to excessive noxious temperatures. The average power was 6.5 W, with an energy density of 1.5 10−2 Wh L−1. The air SDBD worked in the ozone mode, concentration typically 200–300 ppm, exceeded significantly nitrogen oxide product concentration, typically 30–40 ppm of NO2 and 2–3 ppm of N2O13,53.

Figure 2 shows low resolution emission spectra of filamentary SDBD driven in humid air revealing strong bands of the second positive system (SPS) (C3Πu → B3Πg) of N2 and first negative system (FNS) (B2Σu+ → X2Σg+) of N2+ in the UV spectral range. In the Vis-NIR range, we observed characteristic sequences of bands of the first positive system (FPS) (B3Πg → A3Σu+) of N2. Atomic oxygen emission line was clearly observable at 777 nm, indicating the production of atomic oxygen during the plasma on phase. Partially-resolved structures of SPS displayed in Fig. 3 were analysed by means of synthetic models detailed in61. The SPS(0,0) band can be fitted for a given instrumental function by fixing the rotational temperature of 400 ± 25 K. We should notice that this temperature is related to the discharge on time in the surface discharge. SDBD plasma is localized just a few microns above the dielectric surface and this cannot be considered the temperature of the gas in contact with the treated substrate. Moreover, considering that the gas is flowing at 7 slm, the residence time in the discharge volume is 64 ms, therefore we can exclude a heat accumulation inside the gap. In Fig. 3 experimental SPS(0,0) band profile is shown together with two synthetic profiles (simulated for rotational temperatures of 300 and 500 K) in logarithmic scale in order to demonstrate sensitivity of the tail of the band (formed by the overlap of R1, R2 and R3 branches) with respect to the rotational temperature of the C3Πu state.

Figure 4a captures the emission formed by Δv = −3 and −2 sequences of the SPS and by Δv = 0 sequence of the FNS. The ratio between FNS (0, 0) and SPS (0, 3) is equal to 0.56 ± 0.02 (Fig. 4b). Using FNS/SPS calibration curves62 we can estimate that the averaged reduced electric field E/N exceeds 900 Td.

Figure 5 shows characteristics vibrational distributions of N2 (C3∏u) evaluated from time and space averaged spectra shown in Fig. 4. Furthermore, the other three vibrational distribution functions (VDFs) corresponding to the Boltzman distributions characterized by the vibrational temperature of 2500 K, 2750 K and 3000 K are shown together with the experimental data points. The VDF is characterized by the non-Boltzman vibrational distribution.

Effects of SDBD treatments on conidial germination

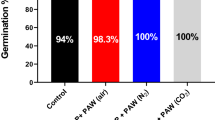

The treatments with plasma significantly inhibited conidia germination of four different fungi exposed to SDBD (Table 1; Fig. 6).

Pre-treatment of water-agar discs before conidia inoculation did not affect their germination, although a slight reduction (4.5–11%) of germinated conidia was observed only in B. cinerea (data not shown). This is a clear indication that substrate chemistry modifications due to plasma interaction is not responsible for inhibition of conidia germination.

As expected, the inhibitory effect of the treatments progressively increased with the extension of the time of exposure to SDBD. Different sensitivities in spore germination were recorded among the fungal species with M. fructicola found as the most sensitive being significantly inhibited (79.1%) after only 30 s of exposure. In B. cinerea a significant reduction (67.4%) in the percentage of germinated conidia was recorded after 2 min of treatment while a complete inhibition of the germination was reached after exposures of 5 min (Fig. 7). At least a 3 min treatment was required to obtain a significant inhibitory effect on conidia germination of A. carbonarius and A. alternata, with different efficacy for the two fungi (88.0% and 18.6%, respectively), while a complete (A. carbonarius; 100%) or almost complete (A. alternaria; 99.8%) inhibition was observed after 5 min.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) observations

SEM analysis was performed to assess the structural damages to fungal conidia produced by plasma just after treatment (Fig. 8). M. fructicola conidia were confirmed as the most sensitive to plasma treatment exhibiting pronounced effects suggesting irreversible damage of the fungal structures after 1 min exposure, or even before (data not shown), corresponding to high inhibition rates recorded for this fungus in the conidial germination assay (Fig. 6). The evolution of damages on conidia surface spanned from cracks to complete removal of the outer layer of the cell wall, shrinkage, and a deeper ablation from the surface of conidia. In the case of B. cinerea, the early effect on the surface mostly consisted of partial ablation of the outer layers of cell wall without any crack while damages appeared irreversible after 3 min of exposure, and after 5 min most conidia were completely destroyed. In the case of M. fructicola, the effect was even stronger with cracks appearing after 1 min, and damages of conidia were more evident following longer treatment times. After 3 min of exposure residues of the destroyed conidia and their leaked cellular contents were visible on the polymeric membrane used as substrate material. In the case of A. carbonarius, the surface ornamentation of conidia was primarily affected by plasma treatment just after 1 min, and more evident after 3 min of treatment when spore walls were smoothed out by plasma ablation and cell wall integrity was obviously compromised in agreement with the results of the conidia germination assay. After 5 min of plasma exposure, conidia appeared almost completely destroyed with cracks, holes on the surface with leakages of cellular content. A. alternata exhibited the most resistant spores, mainly showing shrinkage and ablation processes interesting conidia wall ornamentations, while damage to the cell integrity was only achieved at the longest treatment time (5 min).

Fluorescence-based viability assays

A live/dead viability assay with carboxyfluorescein diacetate (cFDA) and propidium iodide (PI) was applied to B. cinerea conidia. The assay yielded results in agreement with the tests on conidial germination and SEM observations. Unexposed control conidia could be stained with cFDA, but not with PI. As expected, the number of conidia stained with PI increased with the time of exposure to the treatment while those stained with cFDA decreased, and only a few fluorescent conidia were visible after 3 min of treatment (Fig. 9). This indicates that the cell membrane integrity of the spores was affected by the treatment compromising their viability.

Investigations on artificially inoculated cherry fruit

The efficacy of SDBD against B. cinerea and M. fructicola infections on fresh fruits was assessed in in vitro assay on cherry fruit following artificial inoculations (Fig. 10).

During 2017, a preliminary evaluation was carried out on both pre- and post-inoculation treatments, using B. cinerea as inoculum and symptom assessments at 5 different days after inoculation (DAI) (Fig. 11). Until 8 DAI, all treatments significantly (p = 0.01) reduced both disease prevalence (P) and McKinney’s Index (MKI) as compared to the untreated control. In detail, at 2 DAI symptoms were recorded on the untreated control (P = 20%; MKI = 4%) and on fruit treated with 3-min SDBD exposure before pathogen inoculation (P = 10%; IMK = 1%). The pre-inoculation treatment showed an efficacy (measured as Abbott’s Index, AI) up to 75% (P) and 91% (MKI) at 4 DAI and was also able to significantly (p = 0.01) reduce disease incidence (AI = 29%) but not prevalence at 10 DAI. On fruits exposed after inoculations to 1 and 5 min of treatment, symptoms appeared from 4 (P = 20%; IMK = 6%) and 6 (P = 10%; IMK = 4%) DAI, respectively. Higher efficacy was obtained following 5-min exposure with AI ≥ 80% until 8 DAI and the treatment significantly reduced disease prevalence (p = 0.05; AI = 33%) and incidence (p = 0.01; AI = 64%) even at 10 DAI (Fig. 11).

Effect of SDBD treatments on cherry fruit cv. Sweet heart artificially inoculated with B. cinerea (1 × 105 conidia mL−1) during 2017. Bars represent standard error; treatments with the same letter are not statistically different at the probability levels p = 0.05 (small letters) or p = 0.01 (capital letters) with the Tukey’s HSD test.

During 2018, artificial inoculations with B. cinerea were conducted using higher levels of inoculum than in the previous experiment. At 3 DAI, the incidence of grey mould on inoculated fruits was high on both the untreated control (P = 97.5%; IMK = 46.0%) and after 1 min of exposure to SDBD (P = 100%; IMK = 51.5%), while a significant (p ≤ 0.01) reduction of infections was recorded on 5 min-treated fruit (P = 47.5%; IMK = 16.5%). Disease incidence increased at 6 DAI when symptoms were recorded on 100% of untreated or 1 min-treated fruit with 94–98% of MKI, while 82.5% of 5 min-treated fruit were infected and MKI was 64.5% (Fig. 12).

Effect of SDBD treatments on cherry fruits cv. Giorgia artificially inoculated with B. cinerea (5 × 105 conidia mL1) during 2018. Bars represent standard error; treatments with the same letter are not statistically different at the probability levels p = 0.05 (small letters) or p = 0.01 (capital letters) with the Tukey’s HSD test.

On fruits artificially inoculated with M. fructicola, symptoms of brown rot were recorded at 3 DAI with low incidence on 1 min (P = 15%; IMK = 4.5%) and 5 min-treated fruit (P = 2.5%; IMK = 0.5%), statistically different (p ≤ 0.05) from the untreated control (P = 42.5%; IMK = 14.0%). At 6 DAI, disease incidence always reached P values close to 100%, although IMK values on treated fruits (73.0–76.5%) were statistically (p ≤ 0.01) lower than the value of untreated control (88.5%) (Fig. 13).

Effect of SDBD treatments on cherry fruits cv. Giorgia artificially inoculated with M. fructicola (5 × 105 conidia mL−1) during 2018. Bars represent standard error; treatments with the same letter are not statistically different at the probability levels p = 0.05 (small letters) or p = 0.01 (capital letters) with the Tukey’s HSD test.

Discussion

Low temperature plasma (LTP) is a fast, economic and eco-friendly63 technology that can be applied to products improving their commercial quality. It creates a lethal environment for pathogenic bacteria or other types of unwanted microorganisms like molds30,53,64 without any residues or harmful by-products for the environment or the commodity being treated.

Mechanisms of action of LTP are completely different than those of classical decontamination techniques. The antimicrobial activity can be achieved either by UV irradiation leading to the erosion of microorganisms through photon-induced desorption that results from UV photons breaking chemical bonds in cell molecules with the formation of volatile compounds or by etching due to highly energetic ions and reactive species through bombarding and reacting with the surface of the treated materials65. Once the outer layers of the cell are damaged and then cellular integrity compromised, the UV photons can directly hit genetic material leading to DNA damage with the highest killing rate66. Direct DNA damage by direct UV irradiation of microbial cells or spores cannot lead to sterilization due to the minimal depth of penetration of UV photons into cells stacked or covered with various debris. In atmospheric pressure air plasmas, reactive species such as O, OH, and NO2 are believed to play the most crucial role in decontamination from microorganisms. Heat and UV radiation may play secondary roles, and we expect their effects to be either minimal or indirect.

In the present work, we observed different survival rates of spores from different fungal species exposed to SDBD plasma requiring different treatment times to reach significant inhibition of spore germination, reduction of viability and morphological alterations of cell surface up to spore destruction.

The reactive species generated by air plasmas are expected to greatly compromise cell integrity67. ROS and RNS have a direct impact on the cells of microorganisms, and especially on the outermost layer, the polysaccharide-rich wall which envelopes microbial cells. Plasma etching causes the breakdown of bonds, particularly for hydrocarbon compounds. Atomic oxygen and ozone easily react with these open bonds, which facilitates a faster etching of molecules68,69,70. This, in turn, leads to morphological changes of the cell, ranging from reduction in size to the appearance of deep channels, up to complete cellular destruction. The components of the innermost part of the cell envelope, the membrane, are well known to be the targets of oxidation chemistry71,72 with lipids (mostly unsaturated fatty acids) and proteins highly susceptible to attacks by hydroxyl radical (OH)31. This can potentially lead to alterations in overall membrane properties, including stability and permeability.

Many experiments found that low temperature plasmas can inhibit the growth of clinical44,73, food contaminant35,74,75 and phytopathogenic fungi76. Under comparable conditions, however, the fungicidal effect of plasma is weaker than the bactericidal effect due to the differences in structure and composition of prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells. The fungal cell wall is basically made up of chitin, α and β-linked glucans, glycoproteins and pigments77,78. Pigments like melanins may accumulate in fungal structure to protect them from damaging agents such as UV, ionizing, and gamma irradiation, dehydration, extreme temperatures, the action of hydrolytic enzymes, antifungal drugs and free oxygen radicals79.

Melanin may be contained at the cell surface or released to the extracellular space, but its exact location and abundance vary between species. In Aspergillus spp. belonging to the group Nigri, like A. carbonarius, melanins of the dihydronaphthalene (DHN) type are responsible for the dark-brown pigmentation of conidia80 and proved to be involved in their resistance to environmental stress and as virulence factor81. Melanin increases conidia resistance to reactive oxygen species in Aspergillus fumigatus82. In the multicellular conidia of Alternaria spp., melanin is confined to the outer region of the primary cell walls and the septa while secondary cell walls are unmelanized83. DHN melanin also accumulates in the conidiophores, conidia and sclerotia of B. cinerea, giving them their characteristic color as well as in M. fructicola which produces melanized conidia, and fruit mummy consisting of stroma with a highly melanized layer of surface hyphae84,85.

In our experiments, the dark-colored conidia of A. carbonarius and A. alternaria showed higher resistance to the treatment in comparison with lighter pigmented and thinner cell walled B. cinerea and M. fructicola conidia. We can assume that UV photons in the plasma generated at atmospheric pressure should be not enough to have a significant influence on direct inactivation of the fungi because of the protective action of melanin and similar compound embedded in the cell wall. Differences in efficacy of surface etching are more likely related to the cell wall structure and thickness affecting mechanical and chemical strength, as well as to the stacking of spores on their surfaces and the number of cells per spore. Multicellular spores may still have the possibility to germinate if not all the cells in the spore are killed by the treatment. This reduces the overall inhibitory effect on multicellular spores of some fungi, including Alternaria spp.

Our results by SEM analysis showed major structural damages to all the observed fungal conidia after plasma treatment, with etching and perforation of cell walls. Evident disruption of cell walls was noted in the most sensitive species B. cinerea and M. fructicola and at a lower degree in A. carbonarius, thus promoting cellular death. In the most resistant A. alternata, we observed conidia shrinkage, surface changes and cell envelope invaginations. Lysis followed by leakage of cellular content was the main destructive process observed. This is consistent with the decrease in viability of conidia and the increase in their membrane permeability showed by the fluorescence-based assays indicating leakage of cell content and subsequent cell death. Therefore, SEM analysis demonstrated modifications of the external shape of conidia, which could be attributed to the decomposition of organic components by etching and photo-desorption associated with chemical bond breakage, and consequent formation of volatile compounds65.

Until now, few studies have investigated LTP to control postharvest fungal diseases5. Indirect plasma treatments have been successfully applied to inactivate Aspergillus ochraceus, Penicillium expansum and P. digitatum86,87 and other fungi and yeast contaminating fresh produce like fruits and vegetables88.

In addition to direct antimicrobial activity on fresh produce, LTP may also act indirectly by inducing plant defense responses47. The activated chemical species produced by LTP may contribute to both the suggested modes of action by acting rapidly against contaminant microorganisms and as a defense inducer in plants. ROS and RNS have a significant impact on plant cells causing many physiological, biochemical, molecular, and hormonal changes89. Treatments with plasma-activated water induce plant growth as well as endogenous production of ROS and RON, defense hormone metabolism, and up regulation of pathogenesis-related genes in tomato seedlings90, thus enhancing resistance against bacterial leaf spot91. Our results suggest modifications in fruit tissues which can suggest metabolic changes affecting infection establishment. A slight colorimetric change was observed on treated fruits suggesting an increase of contents in polyphenolic compounds after plasma treatment (data not shown). Moreover, the activation of defense responses was indicated by the significant reduction of disease incidence recorded up to 8 DAI on fruits treated before pathogen inoculation.

The consistence and morphology of fruit surface is a challenging point in SDBD plasma decontamination process that requires optimization of the reactor and electrode configurations in order to improve the treatment effectiveness. The quite complex structure and consistence of some fruit tissues, like those of strawberry or blueberry, could hinder full exposure of microorganism cells to plasma effects and create physical barriers that significantly reduces the efficacy of LTP inactivation sometimes causing lesions on the fruit surface that may function as primary infection sites for wound pathogens. On the contrary, smooth and impervious surfaces such as those of cherry fruits or grape, blueberry or currant berries could facilitate deactivation of contaminant spores56,92. The configuration and discharge parameters used in our experiments, even if not completely optimized, allowed to extend the shelf life of cherry fruits of two different cultivars artificially inoculated with two major pathogens (B. cinerea and M. fructicola) affecting fruit quality during postharvest, processing, and storage. These results are comparable to those reported for biocontrol agents or resistance inducers used for the control of postharvest decay of fresh products93. They show a promise for practical application of novel nonthermal plasma technology for the treatment of fresh produce that would allow longer shelf life, less spoilage, and safer products.

Conclusions

In summary, low-temperature air atmospheric pressure plasma represents a quite interesting and innovative control method, alternative to traditional chemicals against plant pathogens, including fungi, particularly those that cause postharvest diseases as well as seed-borne pathogens and mycotoxigenic fungi. We demonstrated that remote plasma treatment by SDBD is effective against conidia of fungi responsible for major economic losses in the agriculture industry, reducing to undetectable levels their viability/germinability on the surface of artificial media. Cell wall disruption and leakage of cell contents were caused by plasma treatments. This demonstrates that treatment can act directly on fungal spores, likely due to the combined effect of active chemical species (i.e., ROS and RNS) and UV lights.

Even if the SDBD device has not been optimized for the treatment of fresh fruit we obtained significant reductions in grey mould and brown rot symptoms on artificially inoculated cherries leading to an increase of their shelf life. Moreover, plasma treated fruits increased their early resistance to infections as a possible consequence of activation of defence responses in the exposed fruit tissues. Further studies will address the feasibility for scale-up of this technology to prototypal scale and commercial scale.

To improve the decontaminant effect on fruit the discharge electrode must be designed to guarantee a homogeneous plasma dose distribution on the surface reaching all the inoculum responsible for infection start up.

Methods

Discharge system

The discharge system includes the modified SDBD reactor used to study the production of active species by SDBDs11, gas feeding unit, discharge energization system, electrical and optical diagnostics and sample holder suitable for inserting biological samples at a selected distance from the discharge surface53. The SDBD reactor (Fig. 14, left) consists of a planar SDBD electrode system placed in a PVC chamber equipped with gas feed input/output ports and a high voltage (HV) interface. This reactor chamber allows the insertion of a sample holder (Fig. 14, right) next to the SDBD surface. The grounded and powered electrodes were deposited on both sides of a thin alumina substrate.

Experimental SDBD setup. The sample holder can accommodate petri dishes containing either cherry fruit or substrates inoculated with conidia. On the right the real sample holder with two cherry showing the inoculation spots.Schematic of the reactor created with Autodesk Fusion 360, ver. 2.0.7046 (https://www.autodesk.com/products/fusion-360/students-teachers-educators).

The nickel-based electrode exposed to the discharge consists of 17 parallel strips (1 mm wide, 75 mm long and separated by 3 mm)11,94. A silver-based induction electrode (74 mm × 74 mm) covers the opposite surface of the alumina plate. The SDBD was powered by an AC power supply composed of the TG1010A Function Generator (TTi), Powertron Model 1000 A RF Amplifier and a high-voltage step-up transformer. Applied AC HV waveform (5 kHz) was amplitude-modulated by a square-wave modulation waveform (fM = 500 Hz) producing 5 kHz sine-wave TON and TOFF periods with a fixed duty cycle D = TON/(TON + TOFF) = 20% and a precise number of sine-wave bursts was selected through an external trigger realized by means of a TG 5011 Function Generator (TTi). We used a LeCroy LC534A digitizing oscilloscope (bandwidth 1 GHz, up to 2 GS/s) to record the voltage–charge, voltage–current characteristics of the discharge. We used a Tektronix P6013A high voltage probe (1,000:1@1 MW, bandwidth 25 MHz) to monitor voltage waveforms. We used a voltage probe (10:1@10 MW, bandwidth 1 GHz) to measure the potential drop on a current sensing shunt resistor (R = 10 Ω) or on a transferred charge measuring capacitor (C = 0.5 μF, both inserted alternately between the induction electrode and ground. The reactor was fed with humid ambient air (RH 40%, T = 25 °C) at a fixed flow rate of 7 slm.

Emission spectroscopy

UV grade quartz frontal windows allow direct visual control of the discharge area and optical emission diagnostics. Andor iStar intensified charge-coupled device (ICCD) DH740i-18U-03 camera was used to register the plasma-induced emission (PIE) collected in this work from the whole SDBD surface. The ICCD was used to register the time-averaged emission spectra through the iHR-320 spectrometer (Jobin-Yvon) equipped with the 150, 1200, 3600 G/mm dispersion gratings. The intensities of the emission spectra acquired by the ICCD detector were corrected for a given detector sensitivity and optical path by means of DH-2000 deuterium-halogen light source (Ocean Optics)53.

Fungal isolates and conidial germination tests

The inhibitory effect of SDBD plasma treatment against B. cinerea, M. fructicola, A. carbonarius and A. alternata was evaluated through conidial germination assays95 at six different exposure time. Single pure isolates of the four species were obtained from the collection of the Plant Pathology section of the Department of Soil, Plant and Food Sciences, University of Bari (Italy). The cultures, stored at −80 °C, were revitalized on potato dextrose agar (PDA: infusion from 200 g peeled and sliced potatoes kept at 60 °C for 1 h, 20 g dextrose, adjusted at pH 6.5, 20 g agar Oxoid No. 3; per liter). Conidia were collected by scraping the surface of seven-day-old colonies grown on PDA at 21 ± 1 °C, exposed for 12 h per day to a combination of two daylight (Osram, L36W/640) and two near-UV (Osram, L36/73) lamps, then suspended with a sterilized loop in sterile distilled water and filtered through glass wood to remove mycelial fragments and conidiophores. Aliquots (10 μL) of conidial suspension (0.5–1 × 105 conidia mL−1) were spotted on discs (6 mm diameter) of water agar (WA: 20 g L−1 of agar Oxoid No. 3), placed on sterile microscope slides and submitted to the plasma treatment. The overall treatment times used were 10 s, 30 s, 1 min, 2 min, 3 min and 5 min. Treated WA disks inoculated with conidia unexposed to SDBD were used as an additional untreated control. The discs were then incubated in a moist chamber at 21 ± 1 °C in the dark, and after 18 h, conidia were fixed with lactophenol cotton blue. Random samples of 100 conidia on each of three replicated spots per condition were observed at ×200 magnification, and germinated conidia were counted. The inhibition of conidial germination was calculated considering the frequency of germinated conidia on untreated control medium.

Morphological observations on plasma treated spores by scanning electron microscopy (SEM)

The effect of plasma on conidial morphology was analyzed collecting microscopic observations by a Hitachi TM3000 SEM (at 10−4 Pa pressure and 15 kV acceleration voltage) as described in a previous study53 in either Observation or Analysis mode. For best image results, samples were previously gold-palladium sputter coated for 120 s (at 10−1 Pa pressure, 10 kV acceleration voltage at 15 mA) by an Edwards Sputter Coater. Polymeric membranes (Nuclepore Polycarbonate, Whatman, Maidstone, UK) with the diameter and pore size of 13 mm and 0.4 µm, respectively, were used as a substrate material for fungal spores by loading conidial suspension (1 × 106 spores mL−1) from B. cinerea, M. fructicola, A. carbonarius and A. alternata.

Fluorescence-based viability assays

The effect on viability and cell membrane integrity was carried out by using the fluorescent probes carboxyfluorescein diacetate (cFDA) and propidium iodide (PI). cFDA acts as a substrate for enzyme activity, that can cross cell membranes. Once inside, it is cleaved by non-specific esterases to release the green-fluorescent carboxyfluorescein, which the cell retains inside. Thus, cell viability can be correlated with its ability to accumulate carboxyfluorescein96. In contrary, the red-fluorescent nucleic acid probe PI can only enter cells that have damaged membranes and is generally excluded from viable cells97. A stock solution of cFDA (Sigma‐Aldrich, Milan, Italy) was prepared in acetone (4.6 mg mL−1) and stored at −20 ± 2 °C in the dark. A stock solution of PI (Sigma‐Aldrich; 0.67 mg mL−1) was prepared in distilled water and stored at 4 ± 1 °C in the dark. Suspensions of B. cinerea conidia were loaded on polymeric membranes as previously described and exposed to plasma. Treated and untreated samples were then incubated with cFDA and PI at a final concentration of 10 µM for 15 min at 25 °C, and the staining of conidia determined visually by microscopy observation. The fluorescence microscope DM5500 (Leica, Wetzlar, Germany) was equipped with an external light source Leica EL6000 and the following filter systems: L5 for blue excitation (excitation filter BP 480/40, dichromatic mirror 505, suppression filter 527/30) and N2.1 for green excitation (excitation filter BP 515–560, dichromatic mirror 580, suppression filter LP590).

Investigations on artificially inoculated cherry fruit

The effectiveness of plasma treatments was evaluated in two different trials on freshly harvested cherry fruits. During 2017, unblemished cv. Sweet heart cherry fruits were wounded with a sterile needle (approximately 4 mm in depth), placed in sterile Petri dishes (55 mm diameter; two replicated fruits per dish) and inoculated at the equatorial region with 10 µL of conidial suspensions (1 × 105 spores mL−1) of B. cinerea. During 2018, selected cv. Giorgia cherry fruits were wounded and each was artificially inoculated at five equidistant points along the equatorial area with 10 µL of conidial suspensions (5 × 105 spores mL−1) of B. cinerea and M. fructicola. After inoculations, fruit surfaces were exposed to SDBD at two different treatment times: 1 or 5 min. Each treatment was conducted on four replicated groups of ten fruits while untreated inoculated and mock fruits inoculated with sterile water served as control checks. Fruits were put inside humid chambers, incubated at 21 ± 1 °C and grey mould or brown rot symptoms were assessed at the following days after inoculation (DAI): (i) 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 (first trial, 2017); (ii) 3 and 6 (second trial, 2018). Evaluations were carried out by using the following empirical scale: 0 = healthy fruit; 1 = 1–5% of infected fruit surface; 2 = up to 25%; 3 = 26–50%; 4 = 51–75%; 5 = 76–100%. The usage of the empirical scale allowed the calculation of the following parameters: 1) Prevalence (P; percentage of infected fruits); (2) McKinney’s Index \((IMK=\frac{\sum (f\cdot v)}{N\cdot X}\cdot 100)\), where: f = frequency of cases falling in each class; v = class value; N = total number of observed cases. Abbott’s Index (AI) was calculated for data of P and MKI of each assessment with the formula: AI = [(Xuntreated − Xtreated)/Xuntreated] × 100.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed by ANOVA using the statistical program CoStat software version 6.45 and Tukey’s HSD (Honestly Significant Difference) procedure to compare all pairs of means at 0.05 and 0.01 confidence interval (p).

References

Hahn, M. The rising threat of fungicide resistance in plant pathogenic fungi: Botrytis as a case study. J. Chem. Biol. 7, 133–141 (2014).

FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP & WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2019. Safeguarding against economic slowdowns and downturns. (2019).

Pagliaccia, D., Ferrin, D. & Stanghellini, M. E. Chemo-biological suppression of root-infecting zoosporic pathogens in recirculating hydroponic systems. Plant Soil 299, 163–179 (2007).

Riggio, G., Jones, S. & Gibson, K. Risk of Human Pathogen Internalization in Leafy Vegetables During Lab-Scale Hydroponic Cultivation. Horticulturae 5, 25 (2019).

Siddique, S. S., Hardy, G. E. S. J. & Bayliss, K. L. Cold plasma: a potential new method to manage postharvest diseases caused by fungal plant pathogens. Plant Pathol. 67, 1011–1021 (2018).

Moreau, M., Orange, N. & Feuilloley, M. G. J. Non-thermal plasma technologies: New tools for bio-decontamination. Biotechnol. Adv. 26, 610–617 (2008).

Sari, A. H. & Fadaee, F. Effect of corona discharge on decontamination of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and E-coli. Surf. Coatings Technol. 205, S385–90 (2010).

Ambrico, P. F. et al. On the air atmospheric pressure plasma treatment effect on the physiology, germination and seedlings of basil seeds. J. Phys. D. Appl. Phys. 53, 104001 (2020).

Riès, D. et al. LIF and fast imaging plasma jet characterization relevant for NTP biomedical applications. J. Phys. D. Appl. Phys. 47, 275401 (2014).

Dilecce, G., Ambrico, P. F., Šimek, M. & De Benedictis, S. OH density measurement by time-resolved broad band absorption spectroscopy in an Ar–H2O dielectric barrier discharge. J. Phys. D. Appl. Phys. 45, 125203 (2012).

Šimek, M. et al. N2(A3Σu +) behaviour in a N2 –NO surface dielectric barrier discharge in the modulated ac regime at atmospheric pressure. J. Phys. D. Appl. Phys. 43, 124003 (2010).

Šimek, M., Ambrico, P. F. & Prukner, V. Evolution of N2(A3Σu +) in streamer discharges: influence of oxygen admixtures on formation of low vibrational levels. J. Phys. D. Appl. Phys. 50, 504002 (2017).

Šimek, M., Pekárek, S. & Prukner, V. Ozone production using a power modulated surface dielectric barrier discharge in dry synthetic air. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 32, 743–754 (2012).

Zhang, Y., Wei, L., Liang, X. & Šimek, M. Ozone production in coaxial DBD using an amplitude-modulated AC power supply in air. Ozone Sci. Eng. 00, 1–11 (2019).

Dobrynin, D., Fridman, G., Friedman, G. & Fridman, A. Physical and biological mechanisms of direct plasma interaction with living tissue. New J. Phys. 11, 0–26 (2009).

Wan, J., Coventry, J., Swiergon, P., Sanguansri, P. & Versteeg, C. Advances in innovative processing technologies for microbial inactivation and enhancement of food safety - pulsed electric field and low-temperature plasma. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 20, 414–424 (2009).

Ehlbeck, J. et al. Low temperature atmospheric pressure plasma sources for microbial decontamination. J. Phys. D. Appl. Phys. 44, 013002 (2010).

Kvam, E., Davis, B., Mondello, F. & Garner, A. L. Nonthermal atmospheric plasma rapidly disinfects multidrug-resistant microbes by inducing cell surface damage. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 56, 2028–2036 (2012).

Imlay, J. A. The molecular mechanisms and physiological consequences of oxidative stress: lessons from a model bacterium. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 11, 443–454 (2013).

Joshi, S. G. et al. Nonthermal dielectric-barrier discharge plasma-induced inactivation involves oxidative DNA damage and membrane lipid peroxidation in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55, 1053–1062 (2011).

Fang, F. C. Antimicrobial reactive oxygen and nitrogen species: concepts and controversies. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2, 820–832 (2004).

Doležalová, E., Prukner, V., Lukeš, P. & Šimek, M. Stress response of Escherichia coli induced by surface streamer discharge in humid air. J. Phys. D. Appl. Phys. 49, 075401 (2016).

Graves, D. B. The emerging role of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in redox biology and some implications for plasma applications to medicine and biology. J. Phys. D. Appl. Phys. 45, 263001–42 (2012).

Pavlovich, M. J., Clark, D. S. & Graves, D. B. Quantification of air plasma chemistry for surface disinfection. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 23, 065036 (2014).

Jeong, J., Kim, J. Y. & Yoon, J. The role of reactive oxygen species in the electrochemical inactivation of microorganisms. Environ. Sci. Technol. 40, 6117–6122 (2006).

Frederickson Matika, D. E. & Loake, G. J. Redox regulation in plant immune function. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 21, 1373–1388 (2014).

Yu, H. et al. Effects of cell surface loading and phase of growth in cold atmospheric gas plasma inactivation of Escherichia coli K12. J. Appl. Microbiol. 101, 1323–1330 (2006).

Sakiyama, Y., Graves, D. B., Chang, H.-W., Shimizu, T. & Morfill, G. E. Plasma chemistry model of surface microdischarge in humid air and dynamics of reactive neutral species. J. Phys. D. Appl. Phys. 45, 425201 (2012).

Machala, Z. et al. Formation of ROS and RNS in water electro-sprayed through transient spark discharge in air and their bactericidal effects. Plasma Process. Polym. 10, 649–659 (2013).

Mai-Prochnow, A., Murphy, A. B., McLean, K. M., Kong, M. G. & Ostrikov, K. (Ken). Atmospheric pressure plasmas: Infection control and bacterial responses. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 43, 508–517 (2014).

Montie, T. C., Kelly-Wintenberg, K. & Roth, J. R. An overview of research using the one atmosphere uniform glow discharge plasma (OAUGDP) for sterilization of surfaces and materials. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 28, 41–50 (2000).

Bettelheim, F. A. et al. Introduction to General, Organic and Biochemistry, 11th edition. (Cengage, 2020).

Deilmann, M., Halfmann, H., Bibinov, N., Wunderlich, J. & Awakowicz, P. Low-pressure microwave plasma sterilization of polyethylene terephthalate bottles. J. Food Prot. 71, 2119–2123 (2008).

Fridman, G. et al. Applied plasma medicine. Plasma Process. Polym. 5, 503–533 (2008).

Selcuk, M., Oksuz, L. & Basaran, P. Decontamination of grains and legumes infected with Aspergillus spp. and Penicillum spp. by cold plasma treatment. Bioresour. Technol. 99, 5104–5109 (2008).

Morfill, G. E., Shimizu, T., Steffes, B. & Schmidt, H. U. Nosocomial infections - A new approach towards preventive medicine using plasmas. New J. Phys. 11, 115019 (2009).

Hasse, S. et al. Atmospheric pressure plasma jet application on human oral mucosa modulates tissue regeneration. Plasma Med. 4, 117–129 (2014).

Rupf, S. et al. Removing biofilms from microstructured titanium ex vivo: a novel approach using atmospheric plasma technology. Plos One 6, 1–9 (2011).

Pan, J. et al. Tooth bleaching using low concentrations of hydrogen peroxide in the presence of a nonthermal plasma jet. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 41, 325–329 (2013).

Heinlin, J. et al. Plasma applications in medicine with a special focus on dermatology. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatology Venereol. 25, 1–11 (2011).

Caprini, J. A., Partsch, H. & Simman, R. Venous ulcers. J. Am. Coll. Clin. Wound Spec. 4, 54–60 (2012).

Foster, K. W., Moy, R. L. & Fincher, E. F. Advances in plasma skin regeneration. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 7, 169–179 (2008).

Bogle, M. A., Arndt, K. A. & Dover, J. S. Evaluation of plasma skin regeneration technology in low-energy full-facial rejuvenation. Arch. Dermatology 143, 168–174 (2008).

Daeschlein, G. et al. Plasma medicine in dermatology: basic antimicrobial efficacy testing as prerequisite to clinical plasma therapy. Plasma Med. 2, 33–69 (2012).

Ling, L. et al. Effects of cold plasma treatment on seed germination and seedling growth of soybean. Sci. Rep. 4, 1–7 (2014).

Sera, B., Sery, M., Gavril, B. & Gajdova, I. Seed germination and early growth responses to seed pre-treatment by non-thermal plasma in hemp cultivars (Cannabis sativa L.). Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 37, 207–221 (2017).

Jiang, J. et al. Effect of seed treatment by cold plasma on the resistance of tomato to Ralstonia solanacearum (bacterial wilt). PLoS One 9, 1–6 (2014).

Filatova, I. et al. The effect of plasma treatment of seeds of some grain and legumes on their sowing quality and productivity. Rom. Reports Phys. 56, 139–143 (2011).

Jiang, J. et al. Effect of cold plasma treatment on seed germination and growth of wheat. Plasma Sci. Technol. 16, 54–58 (2014).

Stolárik, T. et al. Effect of low-temperature plasma on the structure of seeds, growth and metabolism of endogenous phytohormones in pea (Pisum sativum L.). Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 35, 659–676 (2015).

Kitazaki, S., Sarinont, T., Koga, K., Hayashi, N. & Shiratani, M. Plasma induced long-term growth enhancement of Raphanus sativus L. using combinatorial atmospheric air dielectric barrier discharge plasmas. Curr. Appl. Phys. 14, S149–S153 (2014).

Zahoranová, A. et al. Effect of cold atmospheric pressure plasma on the wheat seedlings vigor and on the inactivation of microorganisms on the seeds surface. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 36, 397–414 (2016).

Ambrico, P. F. et al. Reduction of microbial contamination and improvement of germination of sweet basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) seeds via surface dielectric barrier discharge. J. Phys. D. Appl. Phys. 50, 305401 (2017).

Misra, N. N., Schlüter, O. & Cullen, P. J. Cold plasma in food and agriculture: fundamentals and applications, http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/book/9780128013656 (2016).

Hashizume, H. et al. Inactivation effects of neutral reactive-oxygen species on Penicillium digitatum spores using non-equilibrium atmospheric-pressure oxygen radical source. Appl. Phys. Lett. 103, 153708 (2013).

Ziuzina, D., Patil, S., Cullen, P. J., Keener, K. M. & Bourke, P. Atmospheric cold plasma inactivation of Escherichia coli, Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium and Listeria monocytogenes inoculated on fresh produce. Food Microbiol. 42, 109–116 (2014).

Bourke, P., Ziuzina, D., Boehm, D., Cullen, P. J. & Keener, K. The potential of cold plasma for safe and sustainable food production. Trends Biotechnol. 36, 615–626 (2018).

Noriega, E., Shama, G., Laca, A., Díaz, M. & Kong, M. G. Cold atmospheric gas plasma disinfection of chicken meat and chicken skin contaminated with Listeria innocua. Food Microbiol. 28, 1293–1300 (2011).

Ouf, S. A., Basher, A. H. & Mohamed, A. A. H. Inhibitory effect of double atmospheric pressure argon cold plasma on spores and mycotoxin production of Aspergillus niger contaminating date palm fruits. J. Sci. Food Agric. 95, 3204–3210 (2015).

Panngom, K. et al. Non-thermal plasma preatment diminishes fungal viability and up-regulates resistance genes in a plant host. Plos One 9, e99300 (2014).

Šimek, M. Optical diagnostics of streamer discharges in atmospheric gases. J. Phys. DAppl. Phys. 47, 463001 (2014).

Obrusnik, A., Bilek, P., Hoder, T., Šimek, M. & Bonaventura, Z. Electric field determination in air plasmas from intensity ratio of nitrogen spectral bands: I. Sensitivity analysis and uncertainty quantification of dominant processes. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 27, 085013 (2018).

Herrmann, H. W., Henins, I., Park, J. & Selwyn, G. S. Decontamination of chemical and biological warfare (CBW) agents using an atmospheric pressure plasma jet (APPJ). Phys. Plasmas 6, 2284–2289 (1999).

Laroussi, M. Low temperature plasma-based sterilization: overview and state-of-the-art. Plasma Process. Polym. 2, 391–400 (2005).

Moisan, M. et al. Plasma sterilization. Methods and mechanisms. Pure Appl. Chem. 74, 349–358 (2002).

Lerouge, S., Wertheimer, M. R. & Yahia, L. H. Plasma Sterilization: A review of parameters, mechanisms, and limitations. Plasma Polym. 6, 175–188 (2001).

Misra, N. N., Tiwari, B. K., Raghavarao, K. S. M. S. & Cullen, P. J. Nonthermal plasma inactivation of food-borne pathogens. Food Eng. Rev. 3, 159–170 (2011).

Ermolaeva, S. A. et al. Bactericidal effects of non-thermal argon plasma in vitro, in biofilms and in the animal model of infected wounds. J. Med. Microbiol. 60, 75–83 (2011).

Kuzminova, A. et al. Etching of polymers, proteins and bacterial spores by atmospheric pressure DBD plasma in air. J. Phys. D. Appl. Phys. 50, 135201 (2017).

Fricke, K. et al. Atmospheric pressure plasma: a high-performance tool for the efficient removal of biofilms. Plos One 7, e42539 (2012).

Reis, A. & Spickett, C. M. Chemistry of phospholipid oxidation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Biomembr. 1818, 2374–2387 (2012).

Davies, M. J. Protein oxidation and peroxidation. Biochem. J. 473, 805–825 (2016).

Peng, S. et al. Atmospheric pressure cold plasma as an antifungal therapy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 98, 021501 (2011).

Basaran, P., Basaran-Akgul, N. & Oksuz, L. Elimination of Aspergillus parasiticus from nut surface with low pressure cold plasma (LPCP) treatment. Food Microbiol. 25, 626–632 (2008).

Dasan, B. G., Boyaci, I. H. & Mutlu, M. Inactivation of aflatoxigenic fungi (Aspergillus spp.) on granular food model, maize, in an atmospheric pressure fluidized bed plasma system. Food Control 70, 1–8 (2016).

Zhang, X. et al. Atmospheric cold plasma jet for plant disease treatment. Appl. Phys. Lett. 104, 043702 (2014).

Nimrichter, L., Rodrigues, M. L., Rodrigues, E. G. & Travassos, L. R. The multitude of targets for the immune system and drug therapy in the fungal cell wall. Microbes Infect. 7, 789–798 (2005).

Latgé, J. P. & Beauvais, A. Functional duality of the cell wall. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 20, 111–117 (2014).

Belozerskaya, T. A., Gessler, N. N. & Aver’yanov, A. A. Melanin pigments of fungi. In Fungal Metabolites 1–29 (Springer International Publishing), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-19456-1_29-1 (2015).

Gerin, D. et al. Functional characterization of the alb1 orthologue gene in the ochratoxigenic fungus Aspergillus carbonarius (Ac49 strain). Toxins (Basel). 10, 1–16 (2018).

Langfelder, K. et al. Identification of a polyketide synthase gene (pksP) of Aspergillus fumigatus involved in conidial pigment biosynthesis and virulence. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 187, 79–89 (1998).

Tsai, H. F., Chang, Y. C., Washburn, R. G., Wheeler, M. H. & Kwon-Chung, K. J. The developmentally regulated alb1 gene of Aspergillus fumigatus: Its role in modulation of conidial morphology and virulence. J. Bacteriol. 180, 3031–3038 (1998).

Carzaniga, R., Fiocco, D., Bowyer, P. & O’Connell, R. J. Localization of melanin in conidia of Alternaria alternata using phage display antibodies. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 15, 216–224 (2002).

Willetts, H. J. Morphology, development and evolution of stromata/sclerotia and macroconidia of the Sclerotiniaceae. Mycol. Res. 101, 939–952 (1997).

Schumacher, J. DHN melanin biosynthesis in the plant pathogenic fungus Botrytis cinerea is based on two developmentally regulated key enzyme (PKS)-encoding genes. Mol. Microbiol. 99, 729–748 (2016).

Herceg, Z. et al. The effect of high-power ultrasound and gas phase plasma treatment on Aspergillus spp. and Penicillium spp. count in pure culture. J. Appl. Microbiol. 118, 132–141 (2015).

Liu, K., Wang, C., Hu, H., Lei, J. & Han, L. Indirect treatment effects of water-air MHCD jet on the inactivation of Penicillium digitatum suspension. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 44, 2729–2737 (2016).

Pignata, C., D’Angelo, D., Fea, E. & Gilli, G. A review on microbiological decontamination of fresh produce with nonthermal plasma. J. Appl. Microbiol. 122, 1438–1455 (2017).

del Río, L. A. ROS and RNS in plant physiology: an overview. J. Exp. Bot. 66, 2827–2837 (2015).

Adhikari, B., Adhikari, M., Ghimire, B., Park, G. & Choi, E. H. Cold atmospheric plasma-activated water irrigation induces defense hormone and gene expression in tomato seedlings. Sci. Rep. 9, 16080 (2019).

Perez, S. M. et al. Plasma activated water as resistance inducer against bacterial leaf spot of tomato. PLoS One 14, 1–19 (2019).

Fernández, A., Noriega, E. & Thompson, A. Inactivation of Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium on fresh produce by cold atmospheric gas plasma technology. Food Microbiol. 33, 24–29 (2013).

Nunes, C. A. Biological control of postharvest diseases of fruit. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 133, 181–196 (2012).

Ambrico, P. F., Šimek, M., Dilecce, G. & De Benedictis, S. On the measurement of N2(A3Σu +) metastable in N2 surface-dielectric barrier discharge at atmospheric pressure. Plasma Chem. Plasma Process. 28, 299–316 (2008).

De Miccolis Angelini, R. M., Masiello, M., Rotolo, C., Pollastro, S. & Faretra, F. Molecular characterisation and detection of resistance to succinate dehydrogenase inhibitor fungicides in Botryotinia fuckeliana (Botrytis cinerea). Pest Manag Sci. 70, 1884–1893 (2014).

Gahan, P. B. Plant Histochemistry and Cytochemistry. (Academic Press, Inc., 1984).

Brul, S., Nussbaum, J. & Dielbandhoesing, S. Fluorescent probes for wall porosity and membrane integrity in filamentous fungi. J. Microbiol. Methods 28, 169–178 (1997).

Acknowledgements

This work was partially funded by Apulia Region, PO FESR 2007–2013 - Axis I, Line of intervention 1.2., Action 1.2.1, project No. 14 SELGE; by the Italian Ministry for Education (MIUR), PON FESR 2007–2013, grant number PONa3_00395/1 “BIOSCIENZE & SALUTE (B&H) and PONa3_00369 SISTEMA; and by the Italian Ministry of Economic Development (MISE), PON FESR 2014–2020, grant number Protection F/050421/01-03/X32. The research activities of S.P., F.F. and R.M.D.A. were carried out within the framework of the project ‘Epidemiology, genetics of phytopathogenic microorganisms and development of molecular diagnostic methods’ granted by the University of Bari Aldo Moro. M.S. was supported by the Czech Science Foundation (GAČR contract no. GA15-04023S). Authors wish to thank Pasquale Trotti and the Rete Regionale di Laboratori SELGE (Regione Puglia, Accordo di Programma Quadro “Ricerca Scientifica” – II Atto integrativo. Del. CIPE n. 35/05) for the application of the Scanning Electron Microscope platform; Giuliano Puglia Fruit for providing fruit and Dr. Kristo Mucollari and Dr. Vito Liotino and Dr. Vaclac Prukner for their cooperation in the research activities.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.F.A., designed the experiments, performed the main experimental activities, collected and analyzed the data, wrote the main manuscript text, prepare most of the figures (Figs. 1 and 6–13), R.M.D.M.A. designed and performed the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the main manuscript, prepare most of the figures (Figs. 1 and 6–13). M.S. participate to part of the main experimental activities, performed spectroscopic measurements on plasma, prepared Figs. 2–5. F.F. contributed to the experiment design, supervised and complemented the writing and coordinated the collaboration of the authors. C.R. performed experimental activities and contributed to data analysis and manuscript writing. M.A., M.M., A.M. and S.P. contributed to the experiment design and complemented the writing of the manuscript. D.G. performed some experiments. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ambrico, P.F., Šimek, M., Rotolo, C. et al. Surface Dielectric Barrier Discharge plasma: a suitable measure against fungal plant pathogens. Sci Rep 10, 3673 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-60461-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-60461-0

This article is cited by

-

Antifungal activity of Carya illinoinensis extracts against Alternaria alternata pathogen and their cytotoxicity effects on HEK-293T cells: HPLC analysis of bioactive compounds

Discover Applied Sciences (2024)

-

Exploring Factors Influencing the Inhibitory Effect of Volume Dielectric Barrier Discharge on Phytopathogenic Fungi

Plasma Chemistry and Plasma Processing (2023)

-

Surface Barrier Discharge Remote Plasma Inactivation of Aspergillus niger ATCC 10864 Spores for Packaged Crocus sativus

Food and Bioprocess Technology (2023)

-

Decontamination potential of date palm fruit via non-thermal plasma technique

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Arc and pulsed spark discharge inactivation of pathogenic P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, M. canis, T. mentagrophytes, and C. albicans microorganisms

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.