Abstract

All-nonmetal resistive random access memory (RRAM) with a N+–Si/SiNx/P+–Si structure was investigated in this study. The device performance of SiNx developed using physical vapor deposition (PVD) was significantly better than that of a device fabricated using plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition (PECVD). The SiNx RRAM device developed using PVD has a large resistance window that is larger than 104 and exhibits good endurance to 105 cycles under switching pulses of 1 μs and a retention time of 104 s at 85 °C. Moreover, the SiNx RRAM device developed using PVD had tighter device-to-device distribution of set and reset voltages than those developed using PECVD. Such tight distribution is crucial to realise a large-size cross-point array and integrate with complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor technology to realise electronic neurons. The high performance of the SiNx RRAM device developed using PVD is attributed to the abundant defects in the PVD dielectric that was supported by the analysed conduction mechanisms obtained from the measured current–voltage characteristics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Resistive random access memory (RRAM)1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26 has attracted considerable attention over the past two decades due to its simple structure, nonvolatility, high scalability, rapid switching speed, and relatively low operating power. These advantages make RRAM devices suitable for use in future artificial intelligence and neuromorphic computing applications1,2,3,4. A variety of binary composite materials, such as HfOx, TaOx, TiOx, SiOx, and GeOx, that exhibit different device properties have been used as the switching layer. Although various conduction mechanisms for RRAMs have been proposed, the carrier transport behaviour of RRAMs still has not been completely confirmed. To prevent the metal ions from contributing to transport behaviour, we pioneered nonmetal GeOx dielectric RRAM devices6,7,8,9,10 and all-nonmetal N+–Si/SiOx/P+–Si RRAM devices11. In this study, we investigated the all-nonmetal SiNx RRAM devices in which the bond enthalpy of SiN is lower than that of SiO27. The SiNx material has been widely used in the semiconductor industry for various applications, such as the passivation layer of an integrated circuit and the charge-trapping layer of a flash memory. This material can be easily integrated into complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) technology. Moreover, the RRAM device performance strongly depends on the SiNx formation process. A high-performance RRAM device with a large memory window, good endurance, long retention time, and tight device-to-device distribution of the set–reset voltages Vset–Vreset is only achievable when the SiNx layers are formed using low-temperature physical vapor deposition (PVD) rather than the standard plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition (PECVD). The high-performance SiNx RRAM device developed using PVD (PVD-SiNx RRAM device) is linked to the high number of defects and high amount of defect-related current conduction in the SiNx dielectric.

Results

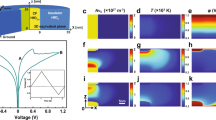

Figure 1(a) displays the forming process of the PVD-SiNx RRAM device and the SiNx RRAM device developed using PECVD (PECVD-SiNx RRAM device). While the forming step of fabricating the PECVD-SiNx RRAM device, the Icc value was increased from 100 μA with a 100-μA step until the resistance state could be switched to the low-resistance state (LRS) at an Icc value of 1 mA. The PVD-SiNx RRAM device exhibited lower Icc and lower forming voltage than those of the PECVD-SiNx RRAM device. These results reflect that the initial PVD-SiNx RRAM device has more defects to form a conduction path than the PECVD-SiNx RRAM device. Figure 1(b) depicts the typical bipolar switching characteristics of both PVD-SiNx and PECVD-SiNx RRAM devices. The PVD-SiNx RRAM device exhibits a significantly lower high-resistance state (HRS) current and a larger resistance window than those of the PECVD-SiNx RRAM device. The much higher HRS current in the PECVD-SiNx RRAM device may be related to the higher Icc and bias voltage values needed during the forming process, where such high power may damage the SiNx and create unrecoverable defects. The asymmetric LRS I-V curve of the PECVD device may be due to the large forming voltage and power to generate excessive defects, which may be partially annihilated by injected electrons during negative voltage swept. Figure 1(c) shows the forming voltage distributions of PVD-SiNx and PECVD-SiNx devices, which are ranged from 6.8 to 8.2 V and from 11.0 to 13.7 V, respectively.

To further understand the carrier conduction mechanism, we analysed the measured data by using various transport mechanisms. Because there is no metal inside the dielectric to form the metallic filament, the conduction mechanism of nonmetal RRAM device is attributed to defect-related hopping conduction10,12,13. Figures 2 and 3 display the analysed conduction mechanisms for PVD-SiNx and PECVD-SiNx RRAM devices, respectively. The very low HRS current in the PVD-SiNx RRAM devices, as presented in Fig. 2, is attributed to the space-charge limited conduction (SCLC) mechanism14,15,16,28. The SCLC regions are divided into three regions by using the transition voltage Vtr and trap-filled limited voltage VTFL. For the low-bias voltage region that is less than Vtr, the current is proportional to voltage and follows Ohm’s law, with an extremely high resistance of approximately 10 GΩ. The current density–voltage (J–V) relationship obtained when the applied voltage is larger than Vtr but lower than VTFL (region 2) can be expressed as follows17,29:

where J, μ, ε, d, and θ represent the current density, electron mobility, static dielectric constant, dielectric layer thickness, and ratio of the free current density to the trapped and free current densities, respectively. In this region, shallow traps are gradually filled by increasing the electric field, and the injected free carrier current density Jfree significantly contributes to the total current density. All the traps at voltages larger than VTFL are filled by injected carriers. A massive number of free carriers contribute to current conduction under a high electric field, thus leading to a steep current–voltage (I–V) slope (region 3) For the PVD device, the currents of HRS I-V curves increase with increasing temperature18. Conversely, the LRS, which exhibited ohmic-like behavior, can be analysed with a slope of 1.39,13.

For the HRS current of the PECVD-SiNx devices presented in Fig. 3(a), the current conduction resembles Poole–Frenkel (P–F) emission19,20,29,30,31,32:

where J, \(\mu \), Nc, qϕT, E, εi, ε0, k, and T are the current density, electron drift mobility, density state in the conduction band, energy level of trap, electric field, dynamic permittivity, vacuum permittivity, Boltzmann’s constant, and absolute temperature, respectively. A trap energy qϕT of 1.1 eV was determined according to the Arrhenius plots presented in Fig. 3(a) at a temperature range from 298 to 398 K. An εi value of 4.3 was obtained from the slope of P–F plots and is lower than the static permittivity (ε = 7)33. P–F emission occurs due to electrons hopping between nearby traps34 which leads to a high HRS current, as shown in Fig. 1(b). Figure 3(b) displays the LRS I–V characteristics of the PECVD-SiNx device that adheres to the SCLC under the most-negative voltage bias region.

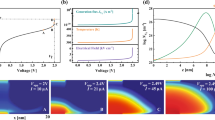

Figure 4 illustrates the potential switching behaviours of the SiNx RRAM device. The PVD-SiNx dielectric has abundant defects in the initial condition because of its room temperature deposition with a low annealing temperature of 200 °C. The current conducting path can be formed and switched to LRS with a relatively low Icc value and voltage. By contrast, the PECVD-SiNx dielectric was deposited at a relatively high temperature of 300 °C, with fewer defects, so the conducting path could not be formed under low Icc and voltage values. Therefore, a high forming voltage of 12 V and a high Icc of 1 mA were required. Under such a high electric field, a large number of Si–N bonds were broken and excessive defects were created. The excessive defects in the PECVD-SiNx layer may create multiple conduction paths and lead to a high HRS current, as shown in Fig. 1(b). To switch from LRS back to HRS, a negative Vreset was applied to rupture the conducting path. Although the conducting paths were ruptured, the electrons in the PECVD-SiNx layer had a high possibility to conduct current in parallel ways via hopping through nearby defects. This further led to the high measured HRS current. Conducting paths can be formed again for electron transportation when a positive Vset is applied to the top electrode.

The deposited SiNx layers were further analysed using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). Figure 5(a,b) depict the XPS data for PVD-SiNx and PECVD-SiNx layers, respectively. The related Si 2p spectra obtained from the XPS data are displayed in Fig. 5(c,d) for the PVD-SiNx and PECVD-SiNx layers, respectively. The N–Si composition of the as-fabricated PVD-SiNx and PECVD-SiNx layers were 0.91 and 1.08, respectively, which indicates a high number of defects inside the PVD-SiNx layer. The nitride vacancies21,35 and Si dangling bonds22,23 can play crucial roles to form the conducting path. The slightly higher oxygen content in the PVD-SiNx layer than in the PECVD-SiNx layer cannot explain the significantly better device performance because the bond enthalpy of SO is higher than that of SN. That is, it is more difficult to break the SO bond to form the defects. Therefore, the XPS results support the proposed model depicted in Fig. 4 and adequately explain the measured I–V characteristics in Fig. 1 and the analysed current conduction mechanisms in Figs. 2 and 3. Such defect-assisted conduction is also the major mechanism for similar GeOx RRAM devices10. The conducting path can be constructed or broken by the different polarities of the applied voltage.

Device endurance and data retention are the crucial characteristics of a nonvolatile memory. Figure 6 shows the retention data of PVD-SiNx and PECVD-SiNx RRAM devices under an 85 °C test condition. The PECVD-SiNx device exhibits a much smaller resistance window and a rapid degradation from an initial value of 56 to 11 after 104 s retention at 85 °C. The poor retention can be ascribed to the high forming voltage with large kinetic energy; then the electrons at 85 °C can partially annihilate or create a leakage path with multiple defects, as shown in Fig. 4. By contrast, the resistance window of an all-nonmetal PVD-SiNx RRAM device slightly decreases from 1.8 × 103 to 1.3 × 103 after a retention time of 104 s at 85 °C. The RRAM device endurance data are shown in Fig. 7, where the Vset and Vreset pulses of +5 V and −5 V were applied to devices with a 1-μs pulse width. The resistance window of the PECVD-SiNx device degraded quickly, and the device failed after 103 endurance cycles. Conversely, a large resistance window of two orders of magnitude was obtained for the PVD-SiNx RRAM device, even after 105 pulse cycles. The excellent endurance of the PVD-SiNx device is related to the high number of defects that can be set and reset easily, with less destruction to the dielectric material.

Figure 8(a,b) display the device-to-device and cycle-to-cycle distributions of Vset and Vreset respectively, which are critical for the RRAM cross-point array24,25,26. The coefficient of variation (CV) was used to study the distribution and is defined as follows:

where σ is the standard deviation, and μ is the mean value. The lower CV value represents a tighter distribution and is crucial for a larger array size26. The device-to-device distributions were extracted from 25 different devices. The CVs of Vset and Vreset of the PVD-SiNx RRAM were 10.7% and 12.1%, respectively, which are remarkably tighter than the 18.3% and 23.2% of PECVD-SiNx devices, respectively. The cycle-to-cycle variations of the first 100 consecutive DC switching cycles, depicted in Fig. 8(b), also show the crucially tighter operation voltage distributions of PVD-SiNx RRAM devices than those of PECVD-SiNx ones. During the forming step, the dielectric soft breakdown must occur by breaking part of the SiN bonds. Based on the preceding discussion, the PECVD-SiNx RRAM device requires a higher Icc value and voltage during fabrication to create a conducting path that has an excessive number of defects and an uncontrollable reset current. These results further lead to poor Vset and Vreset distribution and fewer endurance cycles. One issue of nonmetal RRAM device is the relatively larger operation voltage than that of metal-oxide RRAM device, even though the operation voltage is still much less than that of a flash memory36. One possibility to lower the operation voltage is to use the weak bond-enthalpy GeOx dielectric9, in which the defect-related conduction path can be formed by breaking the dielectric at low energy.

Conclusion

High-performance all-nonmetal N+–Si/SiNx/P+–Si RRAM devices were achieved. The device performance was highly dependent on the deposition process. In this process, the current conduction in the RRAM device was highly related to the defects inside the SiNx layer. The PVD-SiNx RRAM devices exhibited favourable memory characteristics: a large memory window, high pulsed endurance, a long data retention time at 85 °C, and tight device-to-device Vset and Vreset distributions. The PVD-SiNx RRAM device has high potential to realise a large-size cross-point memory array and to be embedded in CMOS technology to realise electronic neurons.

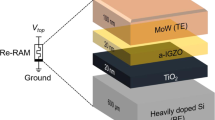

Methods

A P+ silicon wafer was used as a bottom gate. After conducting the RCA clean for the wafer and dipping the wafer into dilute HF to remove the native oxide, a 25-nm-thick SiNx layer was formed by either PVD using electron-beam evaporation or PECVD. Additional furnace annealing was applied to the PVD-SiNx layer at 200 °C in a N2 ambient for 30 min. For the PECVD-SiNx layer, a NH3 of 6 sccm, 8% SiH4 in Ar of 125 sccm, and N2 of 200 sccm were used at a temperature of 300 °C. Finally, the N+–Si top electrode was fabricated as the top electrode with a diameter of 120 μm11. The electrical characteristics were measured using the HP4155B analyser. The pulse stress was generated using a pulse generator (81110, Agilent). Material analysis was performed through XPS analysis by using Thermo Scientific K-Alpha with an X-ray spot size of 400 μm.

References

Wong, H.-S. P. & Salahuddin, S. Memory leads the way to better computing. Nat. Nanotech. 10, 191–194 (2015).

Yao, P. et al. Face classification using electronic synapses. Nat. Commun. 8, 15199 (2017).

Yang, J. J., Strukov, D. B. & Stewart, D. R. Memristive devices for computing. Nat. Nanotechnol. 8, 13–24 (2012).

Gao, B. et al. Modeling disorder effect of the oxygen vacancy distribution in filamentary analog RRAM for neuromorphic computing. IEDM Tech. Dig. 91–94 (2017).

Waser, R., Dittmann, R., Staikov, G. & Szot, K. Redox-based resistive switching memories—Nanoionic mechanisms, prospects, and challenges. Adv. Mater. 21, 2632–2663 (2009).

Chou, K. I., Cheng, C. H., Zheng, Z. W., Liu, M. & Chin, A. Ni/GeOx/TiOy/TaN RRAM on flexible substrate with excellent resistance distribution. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 34, 505–507 (2013).

Cheng, C. H., Chou, K. Y., Chin, A. & Yeh, F. S. Very high performance non-volatile memory on flexible plastic substrate. IEDM Tech. Dig. 512–515 (2010).

Cheng, C. H., Chin, A. & Yeh, F. S. High performance ultra-low energy RRAM with good retention and endurance. IEDM Tech. Dig. 448–451 (2010).

Cheng, C. H., Chin, A. & Yeh, F. S. Novel ultra-low power RRAM with good endurance and retention. Symp. on VLSI Tech. Dig. 85–86 (2010).

Shaposhnikov, A. V., Perevalov, T. V., Gritsenko, V. A., Cheng, C. H. & Chin, A. Mechanism of GeO2 resistive switching based on the multi-phonon assisted tunneling between traps. Appl. Phys. Lett. 100, 243506 (2012).

Yen, T. J., Gismatulin, A., Volodin, V., Gritsenko, V. & Chin, A. All Nonmetal Resistive Random Access Memory. Sci. Rep. 9, 6144 (2019).

Zhang, Y. et al. Study of conduction and switching mechanisms in Al/AlOx/WOx/W resistive switching memory for multilevel applications. Appl. Phys. Lett. 102, 233502 (2013).

Wang, L. et al. Transport properties of HfO2-x based resistive-switching memories. Phys. Rev. B. 85, 195322 (2012).

Kumbhare, P. A selectorless RRAM with record memory window and nonlinearity based on trap filled limit mechanism. IEEE Non-Volatile Memory Technol. Symp. (NVMTS), 1–3 (2015).

Yu, L. E., Kim, S., Ryu, M. K., Choi, S. Y. & Choi, Y. K. Structure effects on resistive switching of Al/TiOx /Al devices for RRAM applications. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 29, 331–333 (2008).

Dong, R. et al. Reproducible hysteresis and resistive switching in metal-CuxO-metal hetero structures. Appl. Phys. Lett. 90, 042107 (2007).

Kim, K. M., Choi, B. J., Shin, Y. C., Choi, S. & Hwang, C. S. Anode-interface localized filamentary mechanism in resistive switching of TiO2 thin films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 91, 012907 (2007).

Gismatulin, A. A., Gritsenko, V. A., Yen, T. –J. & Chin, A. Charge transport mechanism in SiNx-based memristor. Appl. Phys. Lett. 115, 253502 (2019).

Rana, A. M. et al. Endurance and cycle-to-cycle uniformity improvement in tri layered CeO2/Ti/CeO2 resistive switching devices by changing top electrode material. Sci. Rep. 7, 39539 (2017).

Gismatulin, A. A. et al. Charge transport mechanism of high-resistive state in RRAM based on SiOx. Appl. Phys. Lett. 114, 033503 (2019).

Zhang, Z. et al. All-Metal-Nitride RRAM Devices. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 36, 29–31 (2015).

Jiang, X. et al. a-SiNx:H-Based ultra-low power resistive random access memory with tunable si dangling bond conducting paths. Sci. Rep. 5, 15762 (2015).

Kim, S. & Park, G. B. Nonlinear and multilevel resistive switching memory in Ni/Si3N4/Al2O3/TiN structures. Appl. Phys. Lett. 108, 212103 (2016).

Zackriya, M., Kittur, H. M. & Chin, A. A novel read scheme for large size one-resistor resistive random access memory array. Sci. Rep. 7, 42375 (2017).

Zackriya, M., Chin, A. & Kittur, H. M. Impact of current distribution on RRAM array with high and low Ion/Ioff devices. IEEE EDTM Tech. Dig., 156–157 (2017).

Chen, Y. D. & Chin, A. An offset readout current sensing scheme for one-resistor RRAM-based cross-point array. IEEE Electron Device Lett. 40, 208–211 (2019).

Yu, D. S. et al. Lanthanide and Ir-based Dual Metal-Gate/HfAlON CMOS with Large Work-Function Difference. IEDM Tech. Dig. 634–637 (2005).

Rose, A. Space-charge-limited currents in solids. Phys. Rev. 97, 1538–1544 (1955).

Chiu, F. A review on conduction mechanisms in dielectric films. Adv. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2014, 1–18 (2014).

Yeargan, J. R. & Taylor, H. L. The Poole-Frenkel effect with compensation present. J. Appl. Phys. 39, 5600–5604 (1968).

Liu, M. et al. Terahertz-field-induced insulator-to-metal transition in vanadium dioxide metamaterial. Nature. 487, 345–348 (2012).

Chiu, Y. C., King, T. J. & Pan, T. M. Current conduction mechanisms in Pr2O3/oxynitride laminated gate dielectrics. Journal of Applied Physics. 105, 074103 (2009).

Robertson, J. High dielectric constant oxides. Eur. Phys. J. Appl. Phys. 28, 265–291 (2004).

Jonscher, A. K. & Loh, C. K. Poole-Frenkel conduction in high alternation electric fields. Solid State Phys. 4, 1341–1347 (1971).

Hassine, N. B. et al. Dielectrical properties of metal-insulator-metal aluminum nitride structures: Measurement and modeling. J. Appl. Phys. 105, 044111-1–044111-10 (2009).

Tsai, C. Y. et al. Highly-scaled 3.6-nm ENT trapping layer MONOS device with good retention and endurance. IEDM Tech. Dig. 110–113 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This paper’s publication was supported in part by Ministry of Science and Technology of Taiwan, project no. 107-2923-E-009-001-MY3 and Russian Science Foundation (project no. 18-49-08001).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.J. Yen did the experiments; Albert Chin is the principle investigator (PI) to monitor the project; Vladimir Gritsenko is the co-PI for this work. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The results of this research have important contributions for RRAM device.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yen, T.J., Chin, A. & Gritsenko, V. High Performance All Nonmetal SiNx Resistive Random Access Memory with Strong Process Dependence. Sci Rep 10, 2807 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-59838-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-59838-y

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.