Abstract

Trematode infections such as schistosomiasis and fascioliasis cause significant morbidity in an estimated 250 million people worldwide and the associated agricultural losses are estimated at more than US$ 6 billion per year. Current chemotherapy is limited. Triosephosphate isomerase (TIM), an enzyme of the glycolytic pathway, has emerged as a useful drug target in many parasites, including Fasciola hepatica TIM (FhTIM). We identified 21 novel compounds that selectively inhibit this enzyme. Using microscale thermophoresis we explored the interaction between target and compounds and identified a potent interaction between the sulfonyl-1,2,4-thiadiazole (compound 187) and FhTIM, which showed an IC50 of 5 µM and a Kd of 66 nM. In only 4 hours, this compound killed the juvenile form of F. hepatica with an IC50 of 3 µM, better than the reference drug triclabendazole (TCZ). Interestingly, we discovered in vitro inhibition of FhTIM by TCZ, with an IC50 of 7 µM suggesting a previously uncharacterized role of FhTIM in the mechanism of action of this drug. Compound 187 was also active against various developmental stages of Schistosoma mansoni. The low toxicity in vitro in different cell types and lack of acute toxicity in mice was demonstrated for this compound, as was demonstrated the efficacy of 187 in vivo in F. hepatica infected mice. Finally, we obtained the first crystal structure of FhTIM at 1.9 Å resolution which allows us using docking to suggest a mechanism of interaction between compound 187 and TIM. In conclusion, we describe a promising drug candidate to control neglected trematode infections in human and animal health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Trematode infections are a major cause of human disability and mortality in many developing countries, and remain one of the most important challenges for medicine in the 21st century1,2,3. An estimated 250 million people worldwide suffer these infections. Moreover, the Fasciola and Schistosoma parasites infect cattle, sheep and other animals of agricultural importance with estimated agricultural losses of more than US$ 6 billion per year4. In spite of their morbidity and economic impact, neither disease is of sufficient pharmaceutical industry interest for the development of new drugs, such that anthelmintic therapy relies precariously on just two drugs that were developed over 40 years ago: triclabendazole (TCZ) for fascioliasis and praziquantel (PZQ) for schistosomiasis1,2. The over-reliance on TCZ to treat sheep and, to a lesser extent, cattle, has resulted in selection for flukes resistant to TCZ. For PZQ, although clinically-relevant resistance has yet to emerge, resistance has been reported on occasion in the field and in various experimental settings5,6,7.

An important characteristic in the metabolism of trematode parasites is their dependence on glycolysis as an energy source for survival8. Thus, enzymes in the glycolytic pathway are attractive targets in the search for new small molecules chemotherapies9,10. One enzyme, triosephosphate isomerase (TIM; EC 5.3.1.1), is of particular interest as an anthelmintic target8. TIM catalyzes the isomerization of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate and dihydroxyacetone phosphate in the fifth step of the glycolytic pathway11. It also has moonlighting functions, as it is found differently expressed in many types of cancer, it participates in the regulation of the cell cycle, function as an auto-antigen and in the evasion of the immune response, as a virulence factor in some organisms12. Structurally, most of the known TIMs are homodimers, each monomer consisting of eight parallel β-strands surrounded by eight α-helices that, together, form a typical “TIM barrel” fold. The interface between monomers occupies a significant portion of the molecular surface area of each monomer, approximately 1500 Å2 13,14,15. Because TIM is active only in its dimeric form, small molecules that engage the interface may interfere with proper enzyme function16.

Encouraged by the fact that only 50% of the residues involved in the dimer interface are conserved between trematode TIMs and their human ortholog17, we aimed to identify molecules that specifically engage the parasite TIM interface. Accordingly, using 340 in-house compounds, we screened in vitro recombinant FhTIM for low micromolar inactivators. With the best compounds, we performed selectivity assays (using mammalian TIMs) and preclinical studies (toxicology in mammalian cells and in mice). We evaluated their efficacy in vivo in mice infected with F. hepatica and perform X-Ray and docking studies to elucidate the mechanism of inhibition.

Results

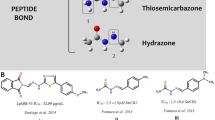

Screening FhTIM

We hypothesized that a TIM dimer interface inactivator would be a successful strategy to identify molecules with selective antiparasitic activity18,19,20. Therefore, we selected 340 compounds from our in-house chemical collection and screened them against the isolated recombinant FhTIM. In this work, the screened chemotypes are represented in Fig. 1 (benzofuroxanes, furanes and thiophenes, 4-substituted-1,2,6-thiadiazines, quinoxaline 1,4-dioxides, phenazine 5,9-dioxides, furoxanes, imidazole N-oxides, indazoles and others). Around 10% of the evaluated compounds were active with an IC50 <100 µM (concentration leading to at least 50% inhibition). Most of the families possess at least one active compound, except for the twenty evaluated quinoxalines from which no active molecules were found. Those families with a high percentage of active derivatives were the 4-substituted-1,2,6-thiadiazines, selenocompounds and phenazines, 60% (9/15), 100% (3/3) and 67% (2/3) active, respectively. We found 30–40% of inactivators among the thiadiazines and their precursors, and the curcuminoids family (Supplementary Table 1S). We established an IC50 <50 µM as the cut-off for good activity (Table 1). Only one active compound belongs to the thiadiazole chemotype (compound 187, Fig. 1), which had the greatest inhibition of the molecular target (Table 1). Interestingly, TCZ (compound 1278 in the collection) inhibited FhTIM with an IC50 of 7 µM (Table 1). In parallel, we performed MicroScale Thermophoresis (MST) with five representative molecules to evaluate their binding affinity. Among them, compound 187 showed the highest affinity for FhTIM with the lowest IC50 (4.0 ± 0.2).

Inhibition cascade for a screen of 340 small molecules with recombinant FhTIM. Structures of the best inhibitors are shown. Compounds are numbered according to Supplementary Table 1S. Three ranges of inhibitory activity were established: IC50 >100 µM (no activity, not shown), IC50 values between 50 and 100 µM (moderate activity) and IC50 <50 µM (good activity).

Then we performed an in vitro selectivity assay of FhTIM as compared to human (HsTIM) and rabbit TIM as a representative ruminant animal21. The best FhTIM inhibitors, 110, 115, 128, 187 and TCZ, were inactive (<20% inhibition) against HsTIM and rabbit TIM at 100 µM.

In vitro and in vivo anti-parasite activity of the compounds

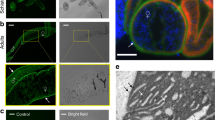

As a proof of concept, we tested the best FhTIM inactivators against F. hepatica and S. mansoni parasites. Also, we use compound 191 as a non-inhibitor which has a closely related structure to that of compound 187. Some compounds were able to kill 100% of the newly excysted juvenile (NEJ) F. hepatica within 4 to 48 h (Table 2 and Fig. 2). Also, some of the compounds that were active against NEJ markedly affected S. mansoni, notably compound 187, which, in the first 24 h, was lethal to somules, and decreased the motility of adults and the ability of their oral and ventral suckers to adhere to the floor of the culture dish well (Tables 2 and S2). In parallel, these compounds were assayed to characterize their non-specific toxicity against murine macrophages and bovine sperm. Both models are recommended by FDA as an in vitro prediction of toxicology22. We used fixed doses of 25 and 100 µM of compound to test against the mammalian cells: when the IC50 vs. the parasite was at least 10 times less than the IC50 vs. the mammalian cells, we considered these compounds as non-toxic (NT); if not, they were classified as toxic (T) (Table 2).

Then we tested the biological activity of compound 187 against the adult form of F. hepatica and S. mansoni. This compound was selected as it was the most potent and least toxic of our compounds and is active against the juvenile stages of F. hepatica. In the case of F. hepatica, parasites were affected in the first 4 h at 10 µM (Fig. 2), ultimately leading to the death of all the parasites after 24 h. The S. mansoni parasite was also susceptible to compound 187, showing decreased motility and loss of their ventral sucker adherence to the plate floor after 24 h at only 5 µM.

Furthermore, the ability/potency of compound 187 to protect animals from F. hepatica infection was evaluated. To this end, BALB/c mice were infected with 10 F. hepatica metacercariae and one week later, compound 187 or TCZ were inoculated orogastrically. Compound 187, together with TCZ, protected mice from the infection since they presented less severe clinical signs, including a decrease in liver necrosis, hemorrhage and splenomegaly (Fig. 3A). Then the transaminase profile was according to a healthy liver (Fig. 3B).

Finally, to get toxicological information about compound 187, we performed acute oral toxicology (up-and-down experiment), which demonstrated an LD50 of ≥2000 mg/kg body weight in mice. An in silico exploration of the pharmacokinetic properties of compound 187 compared to the drug-likeness of other drugs gave parameters similar to those of the reference drug TCZ (Supplementary Fig. 2S).

Crystal structure of FhTIM and prediction of compounds binding sites

To elucidate the molecular basis of FhTIM inhibition, we obtained the crystal structure of FhTIM at 1.9 Å resolution. The asymmetric unit displays three FhTIM dimers (Fig. 4A). Each protomer shows a typical (β/α)8 TIM-barrel fold. The R.M.S.D. between FhTIM and human TIM (HsTIM, PDB ID: 4POC)23 protomers is 4.5 Å on all Cα pairs, in spite of only a 68% sequence homology. The catalytic pocket of each protomer in the FhTIM structure is occupied by a sulfate molecule (SO42−), likely from the crystallization buffer. The β/α loop 6 (residues 168–180 of FhTIM) is known to open and close when accommodating the substrate in triosephosphate isomerases. Here, the loops are in the close conformation in all of the protomers of FhTIM (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, the SO42− ion is located in the same position as the phosphate group of the substrates (glyceraldehyde 3 P) in the P. falciparum (Pf TIM) or S. aureus TIM structures (PDB ID: 1LYX15 and 3UWU24, respectively) through similar interactions (Fig. 4C). Indeed, the three unbound oxygen atoms of the O4 tetrahedron in the triose phosphate moiety of Pf TIM interact with the main chain nitrogen of residues G175, S211, G236 and G237, as do 3 out of 4 oxygen atoms of the FhTIM SO42−. The remaining oxygen of the SO42− present in the FhTIM structure (and spatially corresponding to the oxygen atom linking the phosphate to the sugar in the natural substrate) is coordinated by a water molecule roughly located at the position of the distal carbon of the substrate analog in Pf TIM (Fig. 4C). This suggests that the O4 tetrahedron drives the orientation of the substrate in the catalytic pocket.

(A) Top (left) and side (right) view of the content of the asymmetric unit of FhTIM crystal. Dimer A-D: blue tints; dimer B-C: green tints; dimer E-F: yellow tints, with one SO42− molecule (green and yellow) per protomer. Black rectangle highlights the dimer shown in B; (B) Close-up view of dimer A-D with the two SO42− molecules in the active site of each monomer (red and green). Red rectangle highlights the active site of FhTIM shown in (C), left panel; (C) Close-up comparison of the active site of chain A of FhTIM (left panel) with the active site of chain A of PfTIM (PDB ID: 1LYX, right panel) with their liganded SO42− and phosphoglycolate (PGA), respectively. Dashed lines display the hydrogen bonds network of the ligand with neighboring residues/water molecules. The red sphere in the left panel corresponds to water molecule 465 of FhTIM, chain A. Coloring scheme for the ligands’ atoms is: red = oxygen, yellow = phosphorus, green = sulfur, light gray = carbon, orange = chloride. The structure of FhTIM is available in the PDB database (accession ID: 6R8H).

Attempts to understand the mechanism of interaction between the inhibitors and TIM via crystallization did not yield ligand-bound structures. Thus, we used the crystal structure obtained for FhTIM to perform docking studies with our compounds. For each compound, we performed 10 docking calculations including the 10 best poses, i.e., 100 positions selected per compound, which were then clustered and ranked. For each compound, the 10 best positions out of these resulting datasets are included in the supporting material. Docking was performed using four different strategies: “blind” docking on the whole surface of FhTIM in the dimeric and the monomeric form, as well as targeted docking of only the active site with and without the flexibility of the residues in the active site pocket.

No preferential binding sites of the compounds could be identified on the surface of the dimer (Supplementary Material Fig. 1S). However, on the surface of the monomer, the compounds with the best IC50 in Table 1, including the anti-F. hepatica drug, TCZ, bind mostly to one region, which is directly involved in the dimerization (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Material Fig. 1S) with predicted affinities in the micromolar range. Given the size of the dimeric interface, these affinities would probably not be sufficient to disrupt a pre-formed dimer but the compounds might impair the dimerization of monomers or result in a modification of the dimer conformation. Noteworthy, compounds docked on the dimeric interface are predicted to bind close to crucial residues for TIM function. Indeed, the three representative compounds (1278, 110 and 187) are located in close contact of K14 (less than 4 Å), and of these, 187 and 1278 (TCZ) are also predicted to interact with residue H96 (Fig. 5C,E,G). Both K14 and H96 are directly involved in the interaction of TIM with its natural substrate. Thus, the compounds, although not predicted to bind the active site, could inhibit interaction of TIM with its substrate. Anyhow, the docking experiments place the inactivators on a location of the dimer where they could have several effects on TIM function, which now need to be confirmed experimentally.

(A) Display of the best solutions for each compound after docking with compounds 110, 187 and TCZ on the monomeric form of FhTIM. The position of the second monomer in the dimer is displayed as a ghost to show the location of the docked compounds compared to the dimeric interface. Best solution after docking of compounds 110 (B,C), 187 (D,E) and TCZ (F,G) on the FhTIM monomer. (B,D,F): Overall view of the position of the compounds. (C,E,G): close-up views of the position of the compounds with a display of the neighboring residues for which at least one atom lies within 4 Å of the ligand. These views are rotated 90° around the y-axis compared to panels B, D and F for the sake of clarity. The ligand coloring scheme is similar to Fig. 4C.

Discussion

We discovered eleven small molecules belonging to four chemical classes (curcuminoids, thiadiazines, thiosemicarbazides and sulfones) that inhibit recombinant FhTIM. This is the first report of inactivators on this enzyme. Interestingly, we found that TCZ, the reference drug in the treatment of fasciolosis, inhibits FhTIM. TCZ’s mechanism of action is still debated. It has been suggested that TCZ destabilizes β-tubulin25, however, the direct evidence for interaction has not been demonstrated and the mechanism by which the parasites develop TCZ resistance does not appear to be the mutation of tubulin genes25,26. The hypothesis that TCZ interacts with tubulin is based on the better-known mode of action of other benzimidazoles for which tubulin interaction has been demonstrated in antiparasitic and anticancer applications27. The evidence for TCZ/tubulin interaction is weak and the structure of TCZ, in any case, is different from other anti-parasitic benzimidazoles28. Our findings open the possibility of exploring TIM as a biological target of this drug.

Solving the first crystal structure of FhTIM provided insights both on the enzyme’s binding to natural substrates in the active site and the specific mechanism of action of our inactivators. Concerning the binding of substrate, the presence of a sulfate ion in the active site, and the fact that is orientated and coordinated as is the phosphate moiety of the substrate analog in Pf TIM11, suggests that the O4 tetrahedron is important for the correct orientation and coordination of the TIM substrate. Moreover, our finding of similar interactions between the SO42− and the phosphate moieties of the natural substrate in the active site could explain why sulfate ions inhibited Trypanosoma TIM13,29 in vitro and may facilitate orienting drug-design efforts focused on sulfated/phosphorylated molecules.

Docking suggests that the efficient FhTIM inactivators (187, 110, 116, 128), including TCZ, bind tightly at the enzyme’s dimerization interface (Fig. 5). As this dimerization is necessary for TIM function, our data suggest that our compounds could inhibit TIM by modifying or blocking the interface of the dimer. Inhibitors of protein:protein interactions have been sought for more than thirty years19 and although our compounds are small compared to the TIM interface, previous examples of small molecules inhibiting protein assembly have been described30. Moreover, in our case, as the catalytic site is at the dimeric interface, a disturbance of the topology of the interface, even if not leading to the disassembly of the dimer, could be sufficient to inhibit TIM function. Also, we describe using dynamic studies for T. cruzi TIM a particular movement in solution in the same region that allows strong interactions in small molecules like 18731. Then, a conformational change near the active site, could affect the correct substrate interaction in the active site. In particular, according to our docking results, the region of the dimeric interface putatively targeted by TCZ and our compounds are also close to residues K14 and H96, which are directly involved in the interaction of TIM with its natural substrate. Thus, 187 and TCZ may inhibit the binding of TIM to its substrate by blocking the catalytic loop in the closed, unfavorable conformation. Given the vicinity of the two zones, one cannot exclude that these two effects are involved in the inhibition by compounds 187 and TCZ. Such a dual effect would be very interesting from a pharmaceutical point of view, as the parasites would need to accumulate mutations against these two effects in order to become resistant to the treatment. Our docking data are in silico predictions, but they warrant further experiments to seek for a functional confirmation of the molecular mechanisms of inhibition by compounds 187 and TCZ.

The best FhTIM inactivators are lethal to both juvenile and adult forms of F. hepatica, essentially immobilizing both developmental forms at 10 µM after 4 h, a significant improvement over the activity of TCZ against both forms (the effect of TCZ was at 48 h at more than 50 µM). Because TIMs are conserved proteins, including among trematodes8,31, we demonstrated that the best FhTIM inactivator compounds were also active against somules and adults of the S. mansoni bloodfluke. Of these, 144, 1134 and 187, were non-toxic to mammalian cells both herein, and previously at 100 µM against murine macrophages and human peripheral blood mononuclear cells32. They were also more active against both parasites than the reference drug TCZ and its active metabolite 1293 (6-chloro-5-(2,3-dichlorophenoxy)-2-(methylsulfonyl)-1H-benzo[d]imidazole). The biological activity of 187 was observed immediately and developed faster than the other compounds. By contrast, it took several hours for TCZ to kill Fasciola NEJ in vitro. In addition, 187 displayed low toxicity in the acute oral toxicity assay. Moreover, its pharmacokinetic profile is comparable with commercially available drugs. This compound is also a moderate inhibitor of thioredoxin glutathione reductase (an essential core enzyme for redox homeostasis in flatworm parasites) and showed effect on NEJ and Echinococcus granulosus protoscolex at 48 h and a fixed dose of 20 µM32. Also compound 187 protect mice infected with F. hepatica like the reference drug. We identified compound 187 as a lead candidate and obtained FhTIM structure at 1.9 Å resolution crystals to understand the compound’s ligand-binding characteristics. Compound 187 is the first, selective, anthelmintic TIM inactivator reported with in vivo efficacy. Altogether, our findings suggest that compound 187 is a good drug candidate for the treatment of flatworm infections. As these zoonotic parasites affect human and animal health, our compound 187 seems a good lead to developing a new class of “all-in-one” drugs with broad anti-parasitic potential.

Methods

Chemicals

The studied compounds were selected from our chemo library (LIDENSA) using the following criteria: (i) agents belonging to T. cruzi TIM inhibitors, or/and (ii) symmetrical and benzo-containing agents, structurally related to previously described TIM inhibitors. The selected compounds belong to fourteen chemotypes: 1-thiazoles, 2-thiadiazoles, 3-quinoxalines, 4-thiosemicarbazides, 5-steroids, 6-thiadiazines and precursors, 7-selenocompounds, 8-hydrazines, 9-curcuminoids, 10-indazoles, 11-imidazoles, 12-benzo-furoxanes, 13-triazines, 14-phenazine and 40 molecules with diverse structures not clustered in any family. The purity of the compound was checked only with the active molecules, reaching more than 98% by HPLC-MS. The synthetic procedures for the selected active compounds were described previously compound 18733, thiadiazine compounds34, compound 48235. Compound 1278 is TCZ, which is a commercially available anti-fascioliasis drug (batch PS059349, 98.9% pure from Andres Pintaluba S.A.)

Microscale thermophoresis

MST experiments were performed according to the NanoTemper technologies protocol in a Monolith NT.115 (red/blue) instrument (NanoTemper Technologies, München, Germany36). With this technique, the diffusion behavior of a labeled protein is measured when an infrared light excites the movement of the protein in capillaries. This behavior is the combination of two effects: the fast, local environment-dependent responses of the fluorophore to the temperature jump and the slower diffusive thermophoresis fluorescence changes. It will be modified when the protein is complexed with increasing amounts of unlabeled partners, leading to titration curves that can be fit for Kd estimation36. In practice, FhTIM was labeled with the Monolith His-Tag Labeling Kit RED-tris-NTA (NanoTemper Technologies, München, Germany), as described by the manufacturer. The experiments were performed using 20% and 40% MST power and between 20–80% LED power at 24 °C. The MST traces were recorded using the standard parameters: 5 s MST power off, 30 s MST power on, and 5 s MST power off. The compounds were used at high concentrations (around 5 mM) in the bindings check assay with DMSO at 5% v/v. If the binding check was positive, then the affinity determination was performed with the same experimental settings, with serial 2x dilutions of the compound of interest.

Inhibition of Triosephosphate Isomerase

Expression and purification of proteins: FhTIM, RabbitTIM and HsTIM were expressed in Escherichia coli and purified as described in the literature31,37. After purification, the enzyme, dissolved in 100 mM triethanolamine, 10 mM EDTA and 1 mM dithiothreitol (pH 8), was precipitated with ammonium sulfate (75% saturation) and stored at 4 °C. Before use, extensive dialysis against 100 mM triethanolamine/10 mM EDTA (pH 7.4) was performed. Protein concentration was determined by absorbance at 280 nm for FhTIM (ε = 33,460 M−1cm−1) and for RabbitTIM and HsTIM (ε = 33,460 M−1cm−1). Enzymatic activity was determined following the conversion of glyceraldehydes-3-phosphate into dihydroxyacetone phosphate in a coupled enzyme assay. The decrease in absorbance at 340 nm was followed in a multiplate reader VarioskanTM Flash Multimode Reader (Thermo ScientificTM, Waltham, MA, USA) at 38 °C. The reaction mixture (1 mL, pH 7.4) contained 100 mM triethanolamine, 10 mM EDTA, 0.2 mM NADH, 1 mM glyceraldehydes-3-phosphate and 0.9 units of α-glycerol phosphate dehydrogenase. The reaction was initiated by the addition of 5 ng/mL of the TIM of interest. For the inhibition studies, TIM was incubated at a concentration of 5 mg/mL in a buffer containing 100 mM triethanolamine, 10 mM EDTA, pH 7.4 and 10% of DMSO at 37 °C for 1 h. The mixture also contained the compounds, dissolved in DMSO, at the indicated concentrations. After 1 h, 10 µL were withdrawn and added to a final volume of 100 µL of the reaction mixture for the activity assay. The inhibition assay was performed in a 96-well microplate. None of the molecules tested here affected the activity of α-glycerol phosphate dehydrogenase, the enzyme used in the coupled assay. The IC50 value was taken as the concentration of drug needed to reduce the enzymatic activity to 50% by analysis using OriginLab8.5® sigmoidal regression (% of enzymatic activity vs. the logarithm of the compound concentration). The experiments were performed in triplicate in two independent experiments.

FhTIM crystallization

FhTIM was resuspended at 30 mg/mL in 100 mM triethanolamine/10 mM EDTA (pH 7.4) and stored at −80 °C until use. Protein and crystallization conditions were equilibrated at 19 °C for two hours before preparing the drops. The screening was performed in 96-wells plates using a Mosquito Nanopipetter (TTP Labtech) and commercial screens (Hampton Research, Qiagen) with the sitting drop method, at 19 °C in a Rockimager crystal farm (Formulatrix). Hits grew within 2 weeks in condition B2 of the PEGs II screen (Qiagen). Bigger crystals were grown using the hanging drop method by mixing 1 to 2 µL of protein solution with an equal amount of crystallization condition (0.1 M MES pH 6.5, 0.01 M ZnSO4, 50% PEG550mme). Crystals appeared within two weeks and were directly snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen before being submitted to X-ray diffraction.

X-ray data collection and structure determination

X-ray data were collected at 1.9 Å on beamline ID23-1 from European Synchrotron Radiation Facility, Grenoble, France at 100 K using wavelength λ = 0.97242 Å. Data were processed in space group P31 with cell dimensions a = b = 87.4 Å c = 186.6 Å, α = β = 90° and γ = 120°. Indexation and scaling were performed using XDS and XSCALE programs38. Molecular replacement was performed with the Phaser software39 and using the A chain of Chicken TIM (69% sequence homology, PDB: 4P61)40 as a search model with 6 molecules in the asymmetric unit. Initial refinement was performed with Phenix41 using twin law -h-k, k, -l. Water molecules were added during Phenix refinement. After manual curation of the structure (manual placement of the β/α loop 6 (residues 168–180), manual addition of 6 molecules of SO4, tidying up water molecules) using WinCoot42, further refinements were performed using Refmac 5.8.0238 from the CCP4 suite43. The structure was refined to a final Rwork of 19.6% and Rfree of 22.4%, respectively. Statistics of the X-ray data are shown in Table 3. Geometry analysis using Rampage44 showed 96% of the residues in preferred regions, 3.6% in allowed regions, and 6 residues (0.4%) as Ramachandran outliers (residues 102 and 156 from chain B, E and F).

Docking

The present crystal structure of FhTIM was used as a target in the subsequent docking studies. Compounds were modeled using their SMILES codes from the Chemoffice software. Then, both target protein and ligands were prepared using AutoDockTools v1.5.645: the polar hydrogen atoms were added, the non-polar hydrogens were merged, and the Gasteiger partial atomic charges were calculated. Finally, all the possible rotatable bonds were assigned for each compound. Four distinct docking experiments were then carried out with the program AutoDock Vina v1.1.246: a search on the entire surface of FhTIM in its dimeric and monomeric forms as well as a targeted docking in the active site only, with and without flexibility of the side chains of the residues defining the binding pocket. Compounds were treated as fully flexible in each experiment. The search grid was defined accordingly in order to encompass the considered areas. A visual examination of the resulting poses was performed using PyMOL (Schrödinger, Delano Scientific, LLC, New York, NY, USA).

Cell culture

J774.1 murine macrophage cells (ATCC, USA) were grown in DMEM culture milieu containing 4 mM glutamine and supplemented with 10% FCS20. The cells were seeded in a 96-well plate (5×104 cells in 200 µL culture medium) and incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere for 48 h, to allow cell adhesion prior to drug testing. Afterward, cells were exposed for 48 h to the compounds (25–400 µM) or the vehicle for control (0.4% DMSO), and additional controls (cells in medium) were used in each test. Cell viability was then assessed by measuring the mitochondria-dependent reduction of MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) to formazan. For this purpose, MTT in sterile PBS (0.2% glucose), pH 7.4, was added to the macrophages to achieve a final concentration of 0.1 mg/mL, and the cells were incubated at 37 °C for 3 h. After removing the medium, formazan crystals were dissolved in 180 µL of DMSO and 20 µL of MTT buffer (0.1 M glycine, 0.1 M NaCl, 0.5 mM EDTA, pH 10.5), and the absorbance at 560 nm was measured. The IC50 was defined as the drug concentration at which 50% of the cells were viable, relative to the control (no drug added), and was determined by analysis using OriginLab8.5® sigmoidal regression (% of viable cells vs. the logarithm of the compound concentration). Tests were performed in triplicate.

Cytotoxicity assay on bovine spermatozoa

Semen samples were obtained from a healthy fertile Hereford bull and kept frozen in 0.5 mL straws (extended in Andromed, Minitube, Germany47) under liquid nitrogen until use. The semen used belonged to a single freezing batch that was obtained during a regular collection schedule with an artificial vagina. Samples from three straws were thawed and a sperm pool was prepared in PBS at a concentration of 40 million spermatozoa per mL, then 50 μL of this sperm suspension was carefully mixed with 50 μL of compounds diluted to 100, 50, 25, 12.5 and 6.25 μM or with 1% DMSO in control experiments. Each condition was assayed by duplicate in 96-well plates and controls were assayed by triplicate. Plates were incubated at 37 °C for 1 h with moderate shaking. The motility analysis was carried out using a CASA (Computer Assisted Semen Analyzer) system Androvision (Minitube, Tiefenbach, Germany) with an Olympus BX 41 microscope (Olympus, Japan) equipped with a warm-stage at 37 °C. Each sample (10 μL) was placed onto a Makler Counting Chamber (depth 10 μm, Sefi-Medical Instruments, Israel) and the following parameters were evaluated: percentage of total motile spermatozoa (motility >5 μm/s) and velocity curved line (VCL, >24 μm/s). At least 400 spermatozoa were analyzed from each sample from at least four microscope fields.

In vitro NEJ treatment

F. hepatica metacercariae were acquired from DILAVE, MGAP, Uruguay. NEJ were obtained by in vitro excystement as previously described with minor modifications47. Briefly, metacercariae were incubated with 1% sodium hypochlorite for 5 min at room temperature to remove the outer cyst wall and then washed exhaustively with PBS 200 U/mL Penicillin G sulfate, 200 mg/mL streptomycin sulfate, 500 ng/mL amphotericin B, 10 mM HEPES, counted and divided into groups of around 20 parasites that were transferred to 12 wells tissue culture plates. Parasites were maintained at 37 °C, 5% CO2 in modified Basch’s medium47. At day 1, compounds were added at the indicated concentrations and 0.5% DMSO was added to control groups; each condition was tested in duplicate. NEJ behavior was monitored under a light microscope (Olympus BX41), every day each well was recorded for a minute in order to assess parasite motility and registered using the following score: 3- normally active; 2- reduced activity (sporadic movement); 1- immotile (dead)48.

Ex-vivo in the adult form of F. hepatica

F. hepatica were collected from natural infections of cattle obtained from Casablanca slaughterhouse in Paysandú, Uruguay49. During slaughter (500 animals observed) the livers that showed signs of fascioliasis (thickened canaliculi) were dissected and adult flukes were recovered and kept in PBS at 37 °C until used (no more than 8 h). After flukes emptied their gut content (i.e. the gut was not dark anymore) they were transferred to 6 well plates (one fluke per well) with 2 mL of RPMI 1640 media with 200 U/mL Penicillin G sulfate, 200 mg/mL streptomycin sulfate, 500 ng/mL amphotericin B and 10 mM glucose at 37 °C. Compounds were added at a concentration of 25 µM. The antiparasitic efficacy was expressed as the percentage reduction of the number of flukes in the treated group compared with the control group.

S. mansoni: treatment of somules in vitro and adults ex vivo

The NMRI isolate of S. mansoni was maintained by passage through Biomphalaria glabrata snails and 3–5 week-old, female Golden Syrian hamsters (Charles River, San Diego, CA) as intermediate and definite hosts, respectively. A dose of 600 infective larvae (cercariae) was used to infect hamsters. The acquisition, preparation and in vitro maintenance of S. mansoni post-infective larvae (schistosomula or somules) and adults have been already described5,50,51. Vertebrate animal maintenance and handling at the University of California San Diego Animal Care Facility were in accordance with protocols approved by the university’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC).

Phenotypic screens with somules were performed as described5,50,51. Initially, 100 μL Basch medium52, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 mg/ml streptomycin, 4% heat-inactivated FBS (Corning Mediatech) and 1 μl compound in DMSO were added to clear, 96-well round-bottomed plates (Costar cat.# 3367). Then, 100 μL of the same medium containing 40–50 somules was added to mix the compound with somules (final concentration of DMSO was 0.5%). Assay plates were placed into plastic boxes humidified with wet tissue and then incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 environment. Somules phenotypes were recorded every 24 h up to 72 h using an inverted microscope (Zeiss Axiovert 40 C).

Phenotypic screens with 42-day-old, adult parasites were performed in 24-well plates (Costar cat.# 3526) containing the above medium and approximately five adult males and two females per well. Compound was added in a volume of up to 1 μL DMSO at a concentration of 5 µM (0.05% DMSO final). Assay plates were incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 environment. Parasite phenotypes were recorded at 4, 8 and 24 h using a Zeiss Axiovert 40 C.

Schistosome phenotypic responses were recorded employing a series of ‘descriptors,’ such as rounding, degeneration, overactivity, loss of translucency and changes in motility, as described previously5,50,51,53. To allow for comparisons of compound activity, each descriptor was awarded a value of 1 and these were added up to a maximum ‘severity score’ of 4. Evidence of degeneracy or death was awarded the maximum score of 4. Scores were averaged across duplicate wells for each compound (see details in the supporting information).

Acute oral toxicity

The in vivo 50% lethal dose (LD50) was determined according to the guidelines of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)54,55. All procedures involving animals were approved by the Universidad de la República’s Committee on Animal Research (CHEA Protocol ID 707). Briefly, healthy young adult male BALB/c mice (30 days old, 25 to 30 g) were used in this study. Initially, Compound 187 dissolved in vehicle was administered at 2,000 mg/kg, by orogastric cannula, to one animal. The animal was fasted, maintained, and observed for 14 days according to the OECD guidelines. If the mouse survived for the first 48 h, another animal received the same dose. If this was repeated, a third animal was dosed with 2,000 mg/kg and also observed for 14 days. The experiment ends at 14 days post-administration, if there are no signs of toxicity, the (LD50) is the administered dose, if not, the software AOT AOT425 Stat program recommendation was followed. For the vehicle preparation56 compound 187 was disposed in a mixture, composed of a surfactant (10%), containing Eumulgin HRE 40 (polyoxyl-40hydrogenated castor oil), sodium oleate, and soya phosphatidylcholine (8:6:3), and an oil phase (10%) containing cholesterol and phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) (80%). Compound 187 was pulverized in a mortar with cholesterol, Eumulgin HRE 40, and phosphatidylcholine, then the mixture was dissolved in chloroform and the solvent was evaporated under vacuum to dryness. In parallel, sodium oleate was dissolved in phosphate buffer and left in an orbital shaker for 12 h at room temperature. The former was then added to the evaporated residue, and the mixture was homogenized and placed in an ultrasonic bath at full power for 30 min. The sample was kept at room temperature until use.

Mouse infection with F. hepatica

Six- to eight-week-old female BALB/c mice were obtained from DILAVE Laboratories57 (Uruguay). Animals were kept in the animal house (URBE, Facultad de Medicina, UdelaR, Uruguay) with water and food supplied ad libitum. Mouse handling and experiments were carried out in accordance with strict guidelines from the National Committee on Animal Research (CNEA, Uruguay). All procedures involving animals were approved by the Universidad de la República’s Committee on Animal Research (CHEA Protocol Number: 070153-000180-16). BALB/c mice were orally infected with 10 F. hepatica metacercariae per animal. After 1 week post-infection (wpi), mice were intragastrically inoculated with compound 187 (100 mg/kg) or TCZ (100 mg/kg). At 3 wpi mice were bled and sacrificed. Peritoneal exudate cells, spleens, and livers were removed and analyzed. In order to evaluate the severity of the infection, a disease severity score was developed (Table 3S Supporting Information)57, which was applied in blinded experiments. Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) activity in sera was determined using a commercial kit (Spinreact, Spain) according to the manufacturers’ instructions. PECs from infected and non-infected mice were washed twice with PBS containing 2% FBS and 0.1% sodium azide.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Universidad de la República’s Committee on Animal Research (CHEA Protocol Number: 070153-000180-16 and ID 707) Review Boards. Under the rules of Comisión Nacional de Experimentación Animal: (CNEA, http://www.cnea.gub.uy/).

In silico pharmacokinetic parameters

The predictions were obtained from the online free software SwissADME (http://www.swissadme.ch): a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules58. The smiles codes were provided for the software to calculate and the parameters.

Statistical analysis

All statistical tests were performed using Microsoft Excel. Student’s t-test (two-tailed distribution) was used to calculate P values. The number of experiments and samples was described in the figure legends. All data obtained in more than three experiments or samples show the mean ± s.d. Nonlinear least-squares fitting was performed using KaleidaGraph Ver. 4.5 to evaluate inhibition activity of compounds (IC50).

References

Renslo, A. R. & McKerrow, J. H. Drug discovery and development for neglected parasitic diseases. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2, 701–710 (2006).

Robinson, M. W. & Dalton, J. P. Zoonotic helminth infections with particular emphasis on fasciolosis and other trematodiases. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 364, 2763–2776 (2009).

Tielens, A. G. M., Van Der Meer, P. & Van Den Bergh, S. G. Fasciola hepatica: Simple, large-scale, in vitro excystment of metacercariae and subsequent isolation of juvenile liver flukes. Exp. Parasitol. 51, 8–12 (1981).

Kelley, J. M. et al. Current Threat of Triclabendazole Resistance in Fasciola hepatica. Trends Parasitol. 32, 458–469 (2016).

Abdulla, M. H. et al. Drug discovery for schistosomiasis: Hit and lead compounds identified in a library of known drugs by medium-throughput phenotypic screening. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 3, e478 (2009).

Duthaler, U., Smith, T. A. & Keiser, J. In vivo and in vitro sensitivity of Fasciola hepatica to triclabendazole combined with artesunate, artemether, or OZ78. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 54, 4596–4604 (2010).

Pinto-almeida, A., Mendes, T., Ferreira, P., Belo, S. & De, F. Comparative Proteomics Reveals Characteristic Proteins on Praziquantel-resistance in Schistosoma mansoni. bioRxiv (2018).

Zinsser, V. L., Hoey, E. M., Trudgett, A. & Timson, D. J. Biochemical characterisation of triose phosphate isomerase from the liver fluke Fasciola hepatica. Biochim. 95, 2182–9 (2013).

Zinsser, V. L., Hoey, E. M., Trudgett, A. & Timson, D. J. Biochemical characterisation of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) from the liver fluke, Fasciola hepatica. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Proteins Proteom. 1844, 744–749 (2014).

Dax, C. et al. Selective irreversible inhibition of fructose 1,6-bisphosphate aldolase from Trypanosoma brucei. J. Med. Chem. 49, 1499–1502 (2006).

Mande, S. C. et al. Crystal structure of recombinant human triosephosphate isomerase at 2.8 A resolution. Triosephosphate isomerase-related human genetic disorders and comparison with the trypanosomal enzyme. Protein Sci. 3, 810–821 (1994).

Rodríguez-bolaños, M. & Perez-montfort, R. Medical and Veterinary Importance of the Moonlighting Functions of Triosephosphate Isomerase. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 20, 304–315 (2019).

Rodriguez-Romero, A. et al. Structure and inactivation of triosephosphate isomerase from Entamoeba histolytica. J. Mol. Biol. 322, 669–675 (2002).

Téllez-Valencia, A. et al. Inactivation of Triosephosphate Isomerase from Trypanosoma cruzi by an Agent that Perturbs its Dimer Interface. J. Mol. Biol. 341, 1355–1365 (2004).

Maithal, K., Ravindra, G., Balaram, H. & Balaram, P. Inhibition of Plasmodium falciparum triose-phosphate isomerase by chemical modification of an interface cysteine: Electrospray ionization mass spectrometric analysis of differential cysteine reactivities. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 25106–25114 (2002).

Téllez-Valencia, A. et al. Highly specific inactivation of triosephosphate isomerase from Trypanosoma cruzi. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 295, 958–963 (2002).

Alvarez, G. et al. Massive screening yields novel and selective Trypanosoma cruzi triosephosphate isomerase dimer-interface-irreversible inhibitors with anti-trypanosomal activity. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 45, 5767–5772 (2010).

Saramago, L. et al. Novel and Selective Rhipicephalus microplus Triosephosphate Isomerase Inhibitors with Acaricidal Activity. Vet. Sci. 5, 74 (2018).

Zinzalla, G. & Thurston, D. E. Targeting protein-protein interactions for therapeutic intervention: a challenge for the future. Future Med. Chem. 1, 65–93 (2009).

Aguilera, E. et al. Potent and Selective Inhibitors of Trypanosoma cruzi Triosephosphate Isomerase with Concomitant Inhibition of Cruzipain: Inhibition of Parasite Growth through Multitarget Activity. Chem. Med. Chem 11, 1328–1338 (2016).

Rakus, D., Skalecki, K. & Dzugaj, A. Kinetic properties of pig (Sus scrofa domestica) and bovine (Bos taurus) D-fructose-1,6-bisphosphate 1-phosphohydrolase (F1,6BPase): Liver-like isozymes in mammalian lung tissue. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. - B Biochem. Mol. Biol. 127, 123–134 (2000).

Wei, L. et al. Metabolic profiling studies on the toxicological effects of realgar in rats by (1)H NMR spectroscopy. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 234, 314–25 (2009).

Roland, B. P. et al. Triosephosphate Isomerase I170V Alters Catalytic Site, Enhances Stability and Induces Pathology in a Drosophila Model of TPI Deficiency. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1852, 61–69 (2015).

Mukherjee, S., Roychowdhury, A., Dutta, D. & Das, A. K. Crystal structures of triosephosphate isomerase from methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus MRSA252 provide structural insights into novel modes of ligand binding and unique conformations of catalytic loop. Biochim. 94, 2532–2544 (2012).

Robinson, M. W., Trudgett, A., Hoey, E. M. & Fairweather, I. Triclabendazole-resistant Fasciola hepatica: β-tubulin and response to in vitro treatment with triclabendazole. Parasitology 124, 325–338 (2002).

Rufener, L., Kaminsky, R. & Mäser, P. In vitro selection of Haemonchus contortus for benzimidazole resistance reveals a mutation at amino acid 198 of β-tubulin. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 168, 120–122 (2009).

Ali, I., Lone, M. N. & Aboul-Enein, H. Y. Imidazoles as potential anticancer agents. Medchemcomm 8, 1742–1773 (2017).

Fetterer, R. H. The effect of albendazole and triclabendazole on colchicine binding in the liver fluke Fasciola hepatica. J. Vet. Pharmacol. Ther. 9, 49–54 (1986).

Olivares-Illana, V. et al. Perturbation of the dimer interface of triosephosphate isomerase and its effect on Trypanosoma cruzi. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 1, e01–08 (2007).

McArthur, C., Gallazzi, F., Quinn, T. P. & Singh, K. HIV Capsid Inhibitors Beyond PF74. Diseases. 30, pii: E56 (2019).

Minini, L. et al. Molecular docking and molecular dynamics simulation studies of Trypanosoma cruzi triosephosphate isomerase inhibitors. Insights into the inhibition mechanism and selectivity. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 58, 40–49 (2015).

Ross, F. et al. Identification of thioredoxin glutathione reductase inhibitors that kill cestode and trematode parasites. PLoS One 7, e35033 (2012).

Castro, A. et al. Non-ATP competitive glycogen synthase kinase 3beta (GSK-3beta) inhibitors: study of structural requirements for thiadiazolidinone derivatives. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 16, 495–510 (2008).

Alvarez, G. et al. New chemotypes as Trypanosoma cruzi triosephosphate isomerase inhibitors: a deeper insight into the mechanism of inhibition. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 29, 198–204 (2014).

Gerpe, A. et al. Indazole N-oxide derivatives as antiprotozoal agents: Synthesis, biological evaluation and mechanism of action studies. Bioorganic Med. Chem. 14, 3467–3480 (2006).

Sierra, N. et al. Looking for novel capsid protein multimerization inhibitors of feline immunodeficiency virus. Pharmaceuticals 11 (2018).

Alvarez, G. et al. 1,2,4-thiadiazol-5(4H)-ones: a new class of selective inhibitors of Trypanosoma cruzi triosephosphate isomerase. Study of the mechanism of inhibition. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 5, 981–989 (2013).

Kabsch, W. XDS. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D. Biol. Crystallogr. D66, 125–132 (2010).

Mccoy, A. J. et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 40, 658–674 (2007).

Zhai, X. et al. Enzyme Architecture: The Effect of Replacement and Deletion Mutations of Loop 6 on Catalysis by Triosephosphate Isomerase. Biochem. 53, 3486–3501 (2014).

Adamsa, P. D. et al. The Phenix Software for Automated Determination of Macromolecular Structures. Methods 55, 94–106 (2012).

Emsley, P., Lohkamp, B., Scott, W. G. & Cowtan, K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 66, 486–501 (2010).

Winn, M. D. et al. Overview of the CCP 4 suite and current developments. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D. Biol. Crystallogr. D67, 235–242 (2011).

Lovell, S. C. et al. Structure Validation by C Geometry: and C Deviation. PROTEINS Struct. Funct. Genet. 50, 437–450 (2003).

Morris, G. M. et al. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 30, 2785–2791 (2009).

Trott, O. & Olson, A. J. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization, and multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 31, 455–461 (2010).

Ferraro, F. et al. Identification of Chalcones as Fasciola hepatica Cathepsin L Inhibitors Using a Comprehensive Experimental and Computational Approach. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 10, e0004834 (2016).

Ferraro, F. et al. Cathepsin L Inhibitors with Activity against the Liver Fluke Identified from a Focus Library of Quinoxaline1,4-di-N-Oxide Derivatives. Molecules. 24, 2348 (2019).

Bennett, J. L. & Keehler, P. Fasciola hepatica: Action in vitro of triclabendazole on immature and adult stages. Exp. Parasitol. 63, 49–57 (1987).

Long, T. et al. Phenotypic, chemical and functional characterization of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) as a potential anthelmintic drug target. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 11, e0005680 (2017).

Long, T. et al. Structure-Bioactivity Relationship for Benzimidazole Thiophene Inhibitors of Polo-Like Kinase 1 (PLK1), a Potential Drug Target in Schistosoma mansoni. Plos Negl. Trop. Dis. 10, e0004356 (2016).

Basch, P. F. Cultivation of Schistosoma mansoni In vitro. I. Establishment of Cultures from Cercariae and Development until Pairing. J. Parasitol. 67, 179–185 (1981).

Kyere-Davies, G. et al. Effect of Phenotypic Screening of Extracts and Fractions of Erythrophleum ivorense Leaf and Stem Bark on Immature and Adult Stages of Schistosoma mansoni. J. Parasitol. Res. ID 9431467 (2018).

OECD Guidelines for the Testing of Chemicals, Section 4, Test No. 425: Acute Oral Toxicity - Up-and-Down Procedure. Guidel. Test. Chem. 26 (2001).

Alvarez, G. Bioguided Design of Trypanosomicidal Compounds: in Methods and Protocols. Methods Mol. Biol. 1824, 139–163 (2018).

Álvarez, G. et al. Identification of a new amide-containing thiazole as a drug candidate for treatment of chagas’ disease. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 59, 1398–1404 (2015).

Carasi, P. et al. Heme-oxygenase-1 expression contributes to the immunoregulation induced by Fasciola hepatica and promotes infection. Front. Immunol. 8, 1–15 (2017).

Daina, A., Michielin, O. & Zoete, V. SwissADME: A free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–13 (2017).

Acknowledgements

We thank UK embassy in Uruguay for the supporting grant Science and Innovation Fund UK_ID_2015_1_6 and PROGRAMA ECOS (U14S01) Proyectos conjuntos de investigación científica Uruguay – Francia. We thank the staff of the Protein Science Facility (PSF) of the UMS BioSciences Gerland-Lyon Sud for assistance with the crystallogenesis experiments. We thank the staff of ID23-1 beamline at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (Grenoble, France), and Pr. P. Gouet for his help with the analysis of the diffraction data. Phenotypic screens of S. mansoni at the CDIPD (BMS and CRC) were made possible in part by the grant awards R21AI126296 from the NIH and OPP1171488 from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Dedicated to S.O.A.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

G.A., designed and executed chemical, biochemical and cellular experiments and analyzed data. C.G. helped with the M.S.T. and performed the crystallogenesis experiments and structure determination of FhTIM. X.R. performed docking experiments and analysis. T.F., performed the in vivo animal studies. G.A., C.G., I.C., D.J.T., X.R., C.R.C. wrote the manuscript. A.I. and I.C. optimized the production of FhTIM. F.F. and G.A. performed the T.I.M. inhibition screening. F.F., I.C., G.A. and M.C. evaluated the inhibitors against N.E.J. and adult forms of F. hepatica. I.C., B.M.S. and C.C. evaluated the inhibitors against S. mansoni. L.B. synthesized compounds. F.F. and J.G. performed the sperm toxicity assays. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ferraro, F., Corvo, I., Bergalli, L. et al. Novel and selective inactivators of Triosephosphate isomerase with anti-trematode activity. Sci Rep 10, 2587 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-59460-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-59460-y

This article is cited by

-

TMT proteomic analysis for molecular mechanism of Staphylococcus aureus in response to freezing stress

Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology (2022)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.